Abstract

Binding of TGFβ/BMP factors to their receptors leads to translocation of Smad proteins to the nucleus where they activate transcription of target genes. The two-handed zinc finger proteins encoded by Zfhx1a and Zfhx1b, ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1, respectively, regulate gene expression and differentiation programs in a number of tissues. Here I demonstrate that ZEB proteins are also crucial regulators of TGFβ/BMP signaling with opposing effects on this pathway. Both ZEB proteins bind to Smads, but while ZEB-1/δEF1 synergizes with Smad proteins to activate transcription, promote osteoblastic differentiation and induce cell growth arrest, the highly related ZEB-2/SIP1 protein has the opposite effect. Finally, the ability of TGFβ to mediate transcription of TGFβ-dependent genes and induce growth arrest depends on the presence of endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 protein.

Keywords: Smad proteins/TGFβ/BMP signaling/transcriptional regulation/ZEB-1/δEF1/ZEB-2/SIP1

Introduction

The TGFβ family comprises over 30 different cytokines including TGFβs, BMPs, GDFs and activin and regulates a wide array of biological processes (Massagué and Chen, 2000; Massagué et al., 2000). Binding of these factors to transmembrane type II receptors leads to the phosphorylation of specific type I receptors (also known as activin-like kinases, ALKs), which in turn phosphorylate activating R-Smad proteins (receptor-regulated Smads) (Attisano and Wrana, 2000; Massagué and Wotton, 2000; ten Dijke et al., 2000; Miyazono et al., 2001). In vertebrates, R-Smads include Smad2 and Smad3 (which are activated in response to TGFβ and activins) and Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8 (which are specifically regulated by BMP and GDF factors) (Attisano and Wrana, 2000; ten Dijke et al., 2000; Miyazono et al., 2001). Once activated, R-Smads bind Smad4 and the complexes translocate to the nucleus where they bind to short Smad-binding elements in the promoters of responsive genes (Shi et al., 1998; Zawel et al., 1998). A third group of Smad proteins, I-Smads or inhibitory Smads, including Smad6 and Smad7, antagonize R-Smads (Christian and Nakayama, 1999).

TGFβ proteins are involved in a wide variety of functions during development and differentiation. Interestingly, TGFβ cytokines can both promote or inhibit cell growth, depending on the cell type and, while BMP-4 ventralizes Xenopus embryos, activin and BMP-3 have a dorsalizing effect (Koskinen et al., 1991; Jones et al., 1992; Daluiski et al. 2001). How can such a relatively simple signal transduction scheme account for these pleiotropic (and sometimes antagonistic) biological effects of the TGFβ family? In the last few years, several reports have begun to address this question. A number of proteins that interact with Smads and modulate their transcriptional activity have been identified (reviewed in Massagué and Wotton, 2000; Miyazono et al., 2001). Some of these factors (e.g. TGIF, Ski/SnoN, Evi-1 and SNIP1) inhibit Smad-mediated transcription, whereas others (e.g. FAST, c-jun, TFE-III Mixer/Mix and OAZ) synergize with Smads (Chen et al., 1997; Kurokawa et al., 1998; Labbe et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998; Hua et al., 1998; Luo et al., 1999; Sun et al., 1999; Wotton et al., 1999; Hata et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000). These Smad regulatory factors vary in their scope of action; whereas OAZ specifically synergizes with BMP-2 to activate the Xenopus Vent-2 gene (but not other BMP-responsive genes), Ski/SnoN block both TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways in a more general fashion (Luo et al., 1999; Sun et al., 1999; Hata et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000).

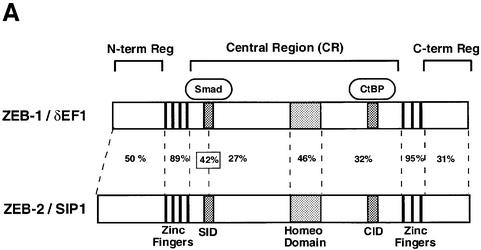

Some Smad coactivators (e.g. FAST, Mix proteins, c-jun, TFE-III, OAZ, etc.) appear to mediate their regulatory activities through binding to specific DNA sites and, therefore, targeting a particular subset of TGFβ/BMP-responsive genes (Miyazono et al., 2001). In this report we provide evidence that the two vertebrate members of the zfh-1 family of two-handed zinc finger factors, ZEB-1/δEF1 (encoded by the Zfhx1a gene) and ZEB-2/SIP1 (encoded by the Zfhx1b gene), have opposing effects on TGFβ/BMP signaling. Both ZEB proteins share a central repressor domain located in between the N- and C-terminal DNA-binding zinc finger clusters (Figure 1A). The repressor domain of both ZEB proteins interacts with the corepressor CtBP (Postigo and Dean, 1999a, 2000), which is also essential for the activity of other key developmental regulatory proteins (reviewed in Chinnadurai, 2002). ZEB proteins have been shown to repress gene expression in several cell types: in hematopoietic cells, ZEB-1/δEF1 negatively regulates the expression of interleukin 2, immunoglobulin µ heavy chain, CD4, GATA-3 and α4 integrin (Williams et al., 1991; Genetta et al., 1994; Postigo and Dean, 1997, 1999b; Postigo et al., 1997; Brabletz et al., 1999; Gregoire and Romeo, 1999); in mesenchymal cells, ZEB-1/δEF1 inhibits p73 gene expression (Fontemaggi et al., 2001); in osteoblasts, ZEB-1/δEF1 protein represses type I and type II collagen expression (Murray et al., 2000; Terraz et al., 2001) and both ZEB proteins repress the E cadherin gene, promoting tumor invasion in epithelial tumors (Grooteclaes and Frisch, 2000; Comijn et al., 2001). Interestingly, ZEB-1/δEF1 protein has also been shown to activate the expression of the ovalbumin and vitamin D3 receptor genes in some cell types, although the molecular mechanism behind this activation effect is unknown (Chamberlain and Sanders, 1999; Lazarova et al., 2001; Dillner and Sanders, 2002).

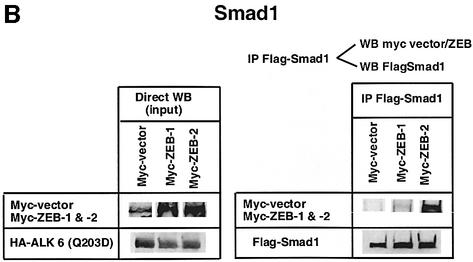

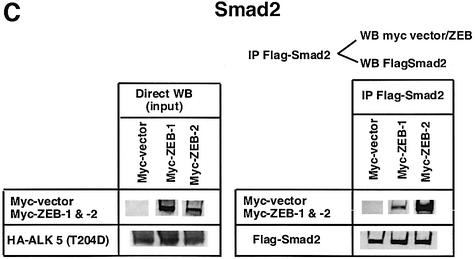

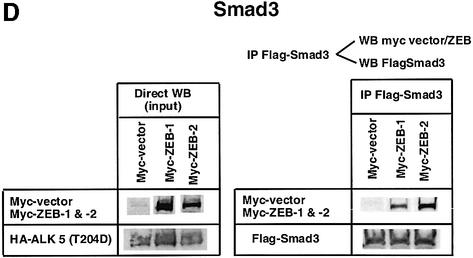

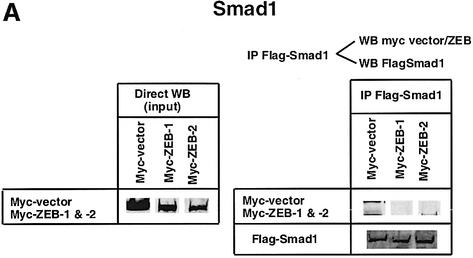

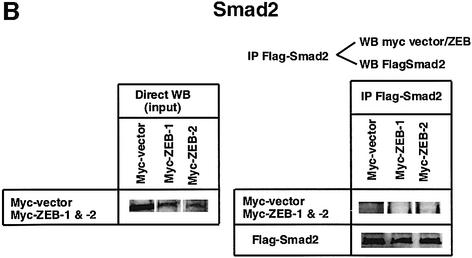

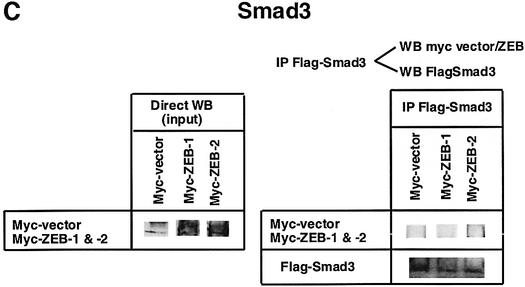

Fig. 1. (A) Schematic representation of the ZEB family (ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1) of two-handed zinc finger factors. The central region (CR) in between both zinc finger clusters act as a repressor domain in part through the recruitment of the CtBP corepressor through a CID. 3′ of the N-terminal zinc fingers there is a region that acts as a SID. (B, C and D) ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 bind to activated R-Smads. 293T cells were cotransfected with the indicated expression vectors: 3 µg of either Flag-tagged Smad1, Smad2 or Smad3, 4 µg of either myc-tagged full-length human ZEB-1/δEF1 or ZEB-2/SIP1 and 0.8 µg of the corresponding constitutively active hemagglutinin-tagged constitutively active ALKs ALK6 (Q203D) for Smad1 (B) and ALK5 (T204D) for Smad2 and Smad3 (C and D). After 48 h, cells lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) for Flag-Smads and the co-immunoprecipitated ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 was detected by western blotting (WB) with 9E10 myc antibody. The input represents 15% of the lysate.

Interestingly, ZEB-2/SIP1 has been shown to interact with R-Smad (Verschueren et al., 1999) and its expression in Xenopus induces neuralization of the embryos and blocks the expression of the activin-dependent Brachyury gene (Remacle et al., 1999; Verschueren et al., 1999; Eisakei et al., 2000; Lerchner et al., 2000). However, no additional information is available regarding the role of ZEB-2/SIP1 in TGFβ/BMP signaling or its mechanism of action. On the other hand, mice carrying a targeted deletion of the ZEB-1/δEF-1 gene present a number of skeletal defects that show a striking parallel with the phenotype of knock out animals for TGFβ gene family members (e.g. BMP-5 and GDF-5), or genes regulated by this family (Msx.1 and Hoxa-13), suggesting that ZEB-1/δEF1 may also play a role in this signaling pathway (Takagi et al., 1998). Patients with heterozygous mutations of the ZEB-2/SIP1 gene present a Mowat–Wilson syndrome with mental retardation, multiple congenital anomalies and, in most cases, Hirschsprung disease (Cacheux et al., 2001; Wakamatsu et al., 2001; Zweier et al., 2002).

All the above results suggest that both ZEB proteins may have important roles in the regulation of Smad signaling. Here, I provide evidence that indeed both proteins bind Smads and regulate TGFβ/BMP signaling in opposing ways. Whereas ZEB-1/δEF1 synergizes with Smads to regulate a number of functions (transcription, differentiation and cell growth arrest), ZEB-2/SIP1 represses Smad functions. Moreover, we provide evidence that TGFβ depends on endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 to mediate some of its actions.

Results

ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 interact with ligand-activated Smads

The ability of ZEB-2/SIP1 to interact with activated R-Smads (Verschueren et al., 1999) and the phenotypic resemblance of mice mutant for ZEB-1/δEF1 with those mutant for some TGFβ family members (or their target genes) (Takagi et al., 1998) suggested that ZEB proteins could be involved in regulating TGFβ signaling. Further supporting this hypothesis, we found that several genes regulated by TGFβ/BMP have ZEB-binding sites in close proximity to the Smad sites (unpublished observations).

I decided to investigate whether ZEB-1/δEF1 could also bind R-Smads. In co-immunoprecipitation experiments ZEB-1/δEF1 did indeed interact with Smad1, 2 and 3 (Figure 1B–D). It is of note that for all three Smads, ZEB-2/SIP1 seemed to bind more efficiently than ZEB-1/δEF1. This interaction requires the phosphorylation of R-Smad as no binding of either ZEB-1/δEF1 or ZEB-2/SIP1 was detected in the absence of the constitutively active type I receptors (Figure 2A–C).

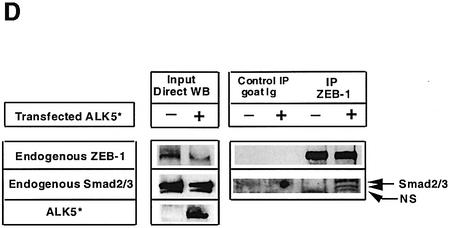

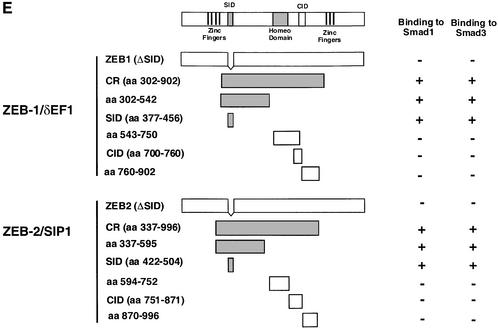

Fig. 2. (A–C) Interaction of ZEB proteins with Smad1, Smad2 and Smad3 requires TGFβ signaling. Experiments were performed as in Figure 1B–D, but in the absence of the corresponding constitutively active ALKs ALK5 (T204D) and ALK6 (Q203D). (D) Interaction between endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 and Smad2 and Smad3. Cell lysates from 293T cells immunoprecipitated with either an antibody against ZEB-1/δEF1 or a control antibody (goat-Ig) in the presence or absence of 20 µg of an expression vector for ALK5 (T204D). Proteins immunoprecipitated by ZEB-1/δEF1 were then western blotted for associated endogenous Smad2 and Smad3. NS indicates a non-specific band. (E) The same region in ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 (Smad-interacting region, SID) mediates their binding to activated Smad1 and Smad3. The indicated myc-tagged constructs for ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 (see Materials and methods for further details) were tested for their ability to interact with Smad1 and Smad3 in the presence of either constitutively active ALK6 (Q203D) and ALK5 (T204D), respectively.

The interaction between ZEB-1/δEF1 and R-Smads was also confirmed at the endogenous level. Endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 was able to interact with Smad2/Smad3, but only when TGFβ signaling was activated by cotransfection of constitutively active TGFβ-RI [(ALK5 (T204D)] (Figure 2D).

I proceeded to identify the region within ZEB-1/δEF1 responsible for the interaction. As shown in Figure 2E, a region located downstream of the N-terminal zinc fingers cluster acted as the Smad-interacting domain (SID) (Verschueren et al., 1999) and its deletion abolished binding of both ZEB proteins to Smad1 and Smad3. The SID is highly conserved across species within both ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1. The homology between the human clones of both ZEB proteins is 42%. Similar levels of expression for wild-type ZEB proteins and their deletion mutants were detected (data not shown).

ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 have opposite effects on TGFβ/BMP-mediated transcription

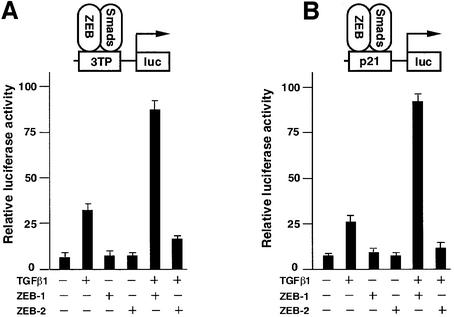

Studies from several groups have shown that both ZEB proteins are active transcriptional repressors (Postigo et al., 1997; Sekido et al., 1997; Remacle et al., 1999; Postigo and Dean, 2000). I decided to investigate whether the interaction of ZEB proteins with R-Smads could repress TGFβ-mediated transcription. Indeed, it was found that ZEB-2/SIP1 inhibited activation by TGFβ of the 3TP, p21, p15 and c-jun promoter reporters (Figure 3A and B and data not shown). Surprisingly, ZEB-1/δEF1 synergized with TGFβ1 to activate transcription of these same reporters (Figure 3A and B; data not shown). Both effects were dependent on TGFβ signaling, as neither ZEB-1/δEF1or ZEB-2/SIP1 significantly affected the basal transcription of these reporters in the absence of TGFβ.

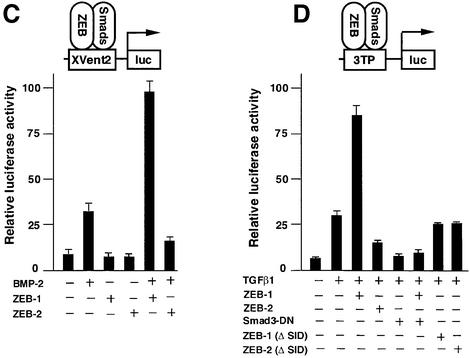

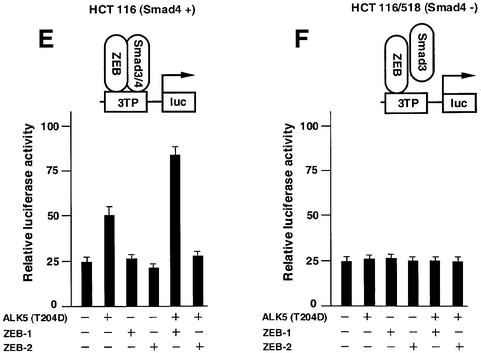

Fig. 3. ZEB-1/δEF1 synergizes with TGFβ/BMP in transcriptional activation, whereas ZEB-2/SIP1 represses. (A and B) Mv1Lu or HaCAT cells (similar results were obtained in both cell types) were cotransfected with 0.3 µg of a firefly luciferase reporter containing the indicated promoter along with either 0.48 µg of the empty vector (CS2MT, not shown) or 0.7 µg of either ZEB-1/δEF1 or ZEB-2/SIP1 expression vectors and stimulated with TGFβ1 (25 pM for Mv1Lu or 100 pM for HaCAT). (C) C2C12 cells were transfected as in (A) and (B) with a firefly luciferase reporter containing the BMP-2-responsive Xvent2 promoter. Where indicated, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-2. (D) Regulation of TGFβ-mediated transcription by ZEB proteins is dependent on the transcriptional activity of R-Smads and requires the SID. Mv1Lu or HaCAT cells were transfected with 0.3 µg of 3TPluc and either 0.48 µg of vector (CS2MT, not shown), 0.6 µg of ZEB-1 (ΔSID) or ZEB-2 (ΔSID) (lacking the SID) or 0.7 µg of full-length ZEB-1 or ZEB-2. Where indicated, an expression vector for Smad3-dominant negative (Smad3-DN, D470E) was cotransfected. (E and F) Regulation of TGFβ-mediated transcription by ZEB proteins requires the presence of Smad4. Smad4 (+/+) HCT 116 cells (E) and Smad 4 (–/–) HCT 116/518 cells (F) were cotransfected as in (A) with 3TP-luc, either ZEB-1 or ZEB-2 and ALK5 (T204D) to activate the TGFβ signaling pathway.

Then, I investigated whether a similar pattern of transcriptional regulation existed for BMP-2 signaling. This is important because the BMP subfamily uses a different set of R-Smads (Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8) than the TGFβ/activin subfamily to mediate its effects and also because of the similarity in the phenotype of ZEB-1/δEF1(–/–) mice to BMP-5 (–/–) and GDF-5 (–/–) mice. As shown in Figure 3C, ZEB proteins also showed opposing effects on the BMP-2-mediated activation of a reporter containing the promoter of the Xenopus Vent-2 gene. Together, these results indicate that ZEB-1/δEF1 can augment transcriptional activation by both TGFβ1 and BMP-2, whereas ZEB-2/SIP1 has the opposite effect.

Regulation of TGFβ-mediated transcription by ZEB proteins requires an active R-Smad–Smad4 complex

The Smad3 (D470E) mutant has been shown to act as a Smad3 dominant-negative and to block TGFβ-mediated transcription by displacing endogenous (wild-type) Smad3 from its DNA-binding sites (Goto et al., 1998). Expression of Smad3 (D470E) also prevented the synergistic effect of ZEB-1/δEF1 in the activation of a TGFβ-dependent promoter (Figure 3D). Since Smad3 (D470E) completely blocked TGFβ-mediated transcription, it was not possible to assess any further effect by ZEB-2/SIP1. This result indicates that the ability of ZEB-1/δEF1 to modulate TGFβ/BMP-mediated transcription depends on functionally active R-Smads. The effect of both ZEB proteins was found to be independent of the way both Smads and ZEB proteins were brought to the promoter, as the transcriptional activity of Smad3 tethered directly to DNA as a Gal4 fusion protein was also augmented by ZEB-1/δEF1 and repressed by ZEB-2/SIP1 (data not shown; Postigo et al., 2003).

Moreover, the regulatory effects of ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 require the formation of a R-Smad–Smad4 complex because neither ZEB protein had any effect on the activation by TGFβ of the 3TP promoter in cells that are mutant for the Smad4(–) gene (Figure 3E and F).

Finally, a direct interaction between ZEB proteins and R-Smads is needed for ZEB proteins to mediate their transcriptional effects because deletional mutants of both ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 lacking the SID failed to affect TGFβ1-dependent transcription (Figure 3D).

The results presented above indicate that ZEB proteins could regulate TGFβ/BMP-mediated transcription in opposing ways. I next wondered whether ZEB proteins could modulate physiological functions mediated by TGFβ and BMP. To address this question, I explored the ability of ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 to regulate the osteogenic differentiation activity of BMP-2 and the growth suppressor effect of TGFβ1.

ZEB-1/δEF1 synergizes with BMP-2 in the induction of alkaline phosphatase

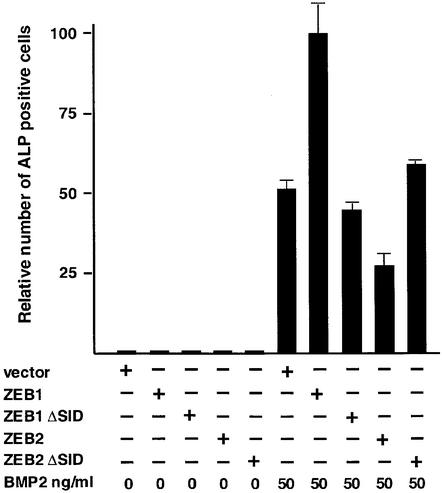

BMP proteins regulate the formation of bone and cartilage both in vivo and in vitro (reviewed in Kingsley, 2001). The ability of ZEB-1/δEF1 to synergize with BMP-2 in transcriptional activation suggested that it might functionally augment BMP signaling. Treatment of mesenchymal C2C12 cells with BMP-2 triggers osteogenic differentiation and expression of osteblastic markers [e.g. alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteopontin, osteonectin, etc.] (Katagiri et al., 1994). As shown in Figure 4, ZEB-1/δEF1 was able to synergize with BMP-2 to induce ALP. This ability to cooperate with BMP-2 is consistent with the skeletal defects observed in ZEB-1/δEF-1 (–/–) mice (Takagi et al., 1998). In contrast, ZEB-2/SIP1 partially inhibited the ability of BMP-2 to induce ALP activity (Figure 4; Tylzanowsky et al., 2001). The functional effect of ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 in this system required the interaction with Smads as (i) both ZEB proteins failed to show any effect in the absence of BMP-2 and (ii) ZEB mutants with a deletion in the SID region failed to regulate ALP activity (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. ZEB-1/δEF1 augments BMP-2-dependent osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal cells. C2C12 were cotransfected with 8 µg of either vector alone (CS2MT) or expression vectors for ZEB-1, ZEB-2 or their ΔSID deletional mutants (ZEB-1 ΔSID and ZEB2 ΔSID) and treated with the indicated amount of BMP-2. After 4 days, cells were assessed for ALP activity as described in Materials and methods.

ZEB-1/δEF1 augments the anti-proliferative signal from TGFβ

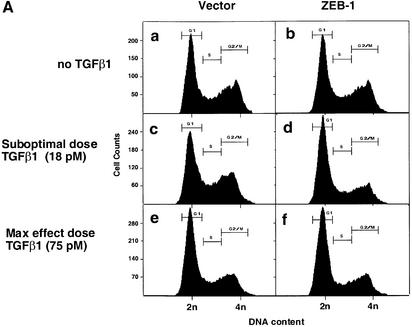

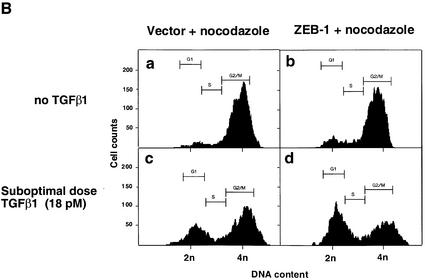

TGFβ blocks proliferation of epithelial, endothelial, lymphoid and neural cells by inducing growth arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (reviewed in de Caestecker et al., 2000; Massagué et al., 2000). Therefore, we asked whether ZEB-1/δEF1 might also synergize with TGFβ in growth arrest. In the absence of TGFβ, expression of ZEB-1/δEF1 did not significantly affect the cell cycle profile of the Mv1Lu epithelial cells (Figure 5A; data not shown). However its expression along with sub-optimal levels of TGFβ (which do not induce a full growth arrest) led to an increased accumulation of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (compare c and d in Figure 5A), implying that ZEB-1/δEF1 is synergizing with TGFβ to arrest cells. Since Mv1Lu cells have a very large number of cells in G1 and in order to demonstrate that the expression of ZEB-1/δEF1 arrested the cells at G1, cells were treated with nocodazole, an inhibitor of microtubule formation that arrests cells in G2/M (Nusse and Egner, 1984; Zhang et al., 2000). Cells would normally progress around the cell cycle and arrest at G2/M due to the nocodazole block. However, if the cells were indeed arrested in a ZEB-1/δEF1- and TGFβ-dependent fashion, they should arrest in G1, unable to progress to G2/M. Indeed, there was a ZEB-1/δEF1–TGFβ-dependent arrest of cells in G1 (Figure 5B, compare c and d, and Figure 5C).

Fig. 5. ZEB-1/δEF1 synergizes with TGFβ to mediate G1 cell cycle arrest. (A) Mv1Lu cells were transfected with 20 µg of the empty vector or ZEB-1/δEF1 along with 1 µg of an expression vector for EGFP (as a marker for sorting transfected cells) and, where indicated, treated with either 18 pM (suboptimal dose) or 75 pM (maximum growth arrest dose) TGFβ1. The cell cycle profile of EGFP-positive cells was analyzed by FACS analysis. (B) As in (A), but cells were preincubated for 48 h with 75 ng/ml nocodazole to induce G2/M arrest (see Materials and methods and Zhang et al., 2000). (C) Mv1Lu cells were transfected with 20 µg of either empty vector, full-length ZEB-1/δEF1 or a mutant of ZEB-1/δEF1 with a deletion of the SID (ZEB-1/δEF1 ΔSID) and EGFP in the presence of nocodazole as in (B). The percentage of cells in G1 phase was determined by FACS and their value compared in the absence or presence of TGFβ1 (both suboptimal and maximum effect doses).

This synergistic effect of ZEB-1/δEF1 with TGFβ depended on the ability of ZEB-1/δEF1 to interact with Smads because the ZEB-1/δEF1 mutant lacking the SID region (ZEB-1/δEF1 ΔSID) did not synergize with TGFβ in G1 arrest (Figure 5C).

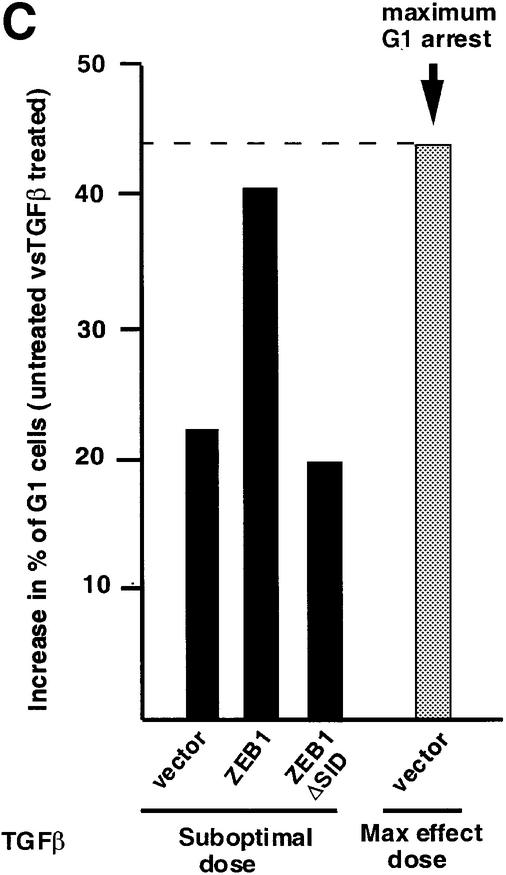

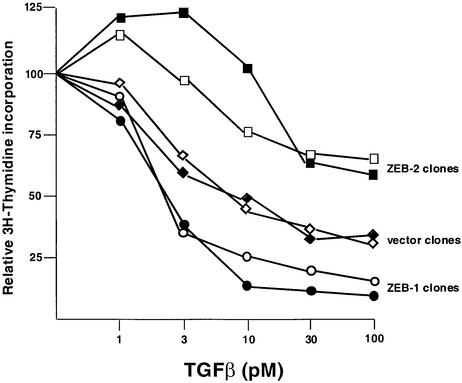

To further examine the effects of the ZEB proteins on TGFβ signaling, stable clones of mink lung epithelial cells expressing both ZEB proteins were generated, and tested to different doses of TGFβ1. As expected, increasing amounts of TGFβ1 induced a dose-dependent inhibition in cell proliferation, as measured by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine (Figure 6). It was found that ZEB-1/δEF1 synergized with TGFβ as its stable overexpression significantly lowered the threshold of TGFβ1 required for growth arrest (Figure 6). In contrast, ZEB-2/SIP1 clones required higher concentrations of TGFβ1 for growth arrest. Taken together, the above results provide evidence that ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 can have opposing effects on the TGFβ signaling pathway, which leads to growth arrest.

Fig. 6. ZEB proteins regulate TGFβ-dependent growth suppression. Mv1Lu cells were stably transfected with either the empty vector, ZEB-1/δEF1 or ZEB-2/SIP1. Stable clones were treated with different doses of TGFβ1 and assessed for cell proliferation by measuring their [3H]thymidine uptake. Two representative clones for each construct are shown.

Endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 in TGFβ signaling

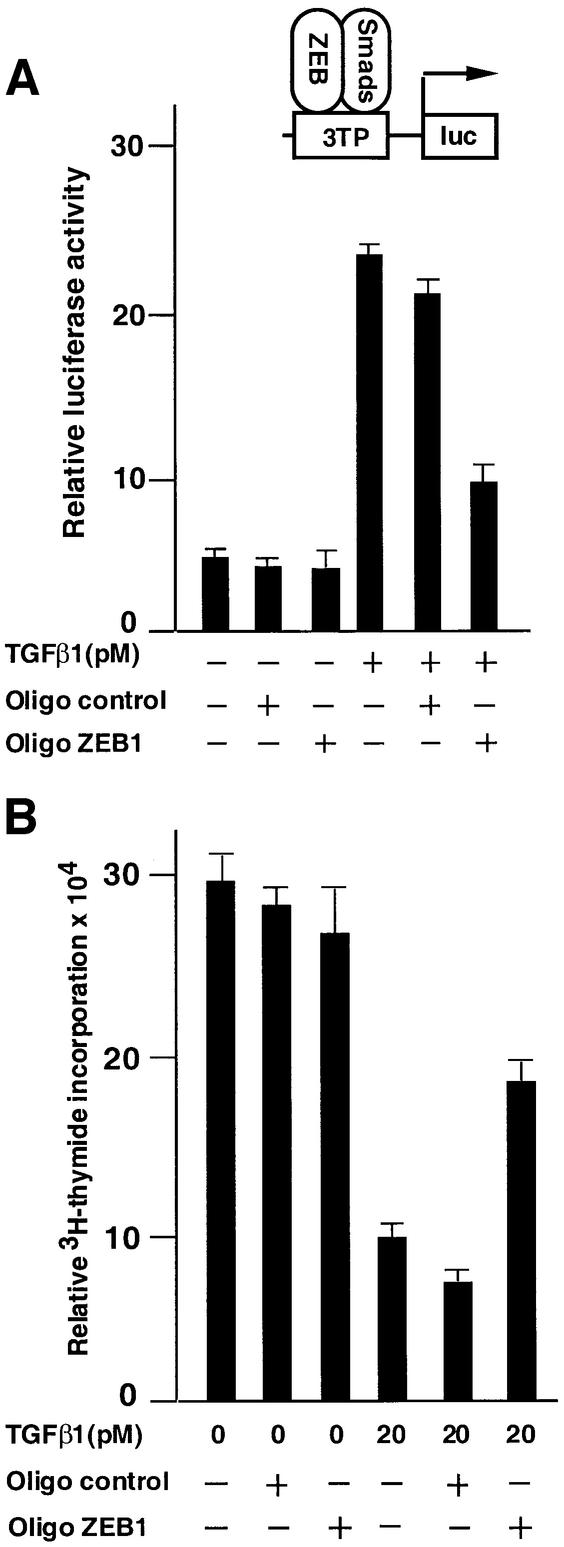

The overexpression of ZEB-1/δEF1 in the above experiments provides strong evidence for a role of ZEB-1/δEF1 in regulating TGFβ family signaling. However, it was still unclear whether endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 indeed contributes to TGFβ signaling in the absence of overexpression. To address this, antisense oligos for ZEB-1/δEF1 mRNA were tested for their ability to affect TGFβ functions, namely the ability to activate transcription and induce cell growth arrest (Figure 7A and B). These antisense oligos partially blocked activation of the 3TP reporter by TGFβ, whereas a scrambled control oligo did not, suggesting that TGFβ-mediated transcription is dependent to some extent upon endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 (Figure 7A).

Fig. 7. Endogenous ZEB/δEF1 mediates TGFβ functions. (A) Endogenous ZEB/δEF1 is important for TGFβ-dependent transcriptional activation. Mv1Lu cells were transfected with 0.3 µg of the TGFβ-responsive 3TP promoter and transcriptional activity assessed as in Figure 3. Where indicated, either antisense oligos to ZEB-1/δEF1 (Oligo ZEB1) or a scrambled control oligo (Oligo control) were added (see Materials and methods). One-tenth of a microgram of SV40βgal was cotransfected to control for transfection efficiency. (B) Endogenous ZEB/δEF1 is important for TGFβ-mediated growth suppression. Mv1Lu cells were transfected with antisense oligos and 0.2 µg of puroBabe, and treated with 1 mg/ml puromycin and 20 pM TGFβ1 for 36 h before the proliferation was assessed by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine.

Likewise, antisense oligos to ZEB-1/δEF1 also significantly reversed the anti-proliferative effect of TGFβ, suggesting that the ability of TGFβ to arrest epithelial cells is dependent, at least in part, on the presence of endogenous ZEB-1/δEF1 protein (Figure 7B).

Discussion

ZEB proteins are members of a large family of zinc finger proteins known as zfh, which was first identified in Drosophila (Fortini et al., 1991; Lai et al., 1991). The genes encoding ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 proteins (Zfhx1 and Zfhx1b, respectively) appear to have evolved from a single Drosophila gene named zfh-1 (Fortini et al., 1991; Lai et al., 1991; Postigo et al., 1999). zfh-1 is crucial for mesodermal (gonadal, skeletal and cardiac muscle) and neural differentiation in flies (Lai et al., 1991, 1993; Broihier et al., 1998; Postigo et al., 1999). The human orthologue of Drosophila zfh-2 seems to be ATBF-1, which has two isoforms: ATBF-1A and ATBF-1B (Miura et al., 1995; Kaspar et al., 1999; Berry et al., 2001). As in the case of ZEB proteins, a recent report demonstrated that ATBF-1A and ATBF-1B have opposing effects on the regulation of muscle differentiation (Berry et al., 2001). These results raise the interesting possibility that the Drosophila zfh family of zinc finger proteins may have evolved in vertebrates into proteins with opposing activities to balance signaling pathways during tissue differentiation and embryonic development (Postigo et al., 2003). ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 are structurally quite similar and both repress transcription of a number of genes involved in differentiation and development. However, the results presented here indicate that ZEB proteins function antagonistically in the regulation of TGFβ/BMP signaling.

Consensus binding sites for the ZEB proteins are evident in the promoters of several target genes for the TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways. Although in overexpression experiments the regulation of Smad-mediated transcription by ZEB proteins could be achieved through direct recruitment of ZEB proteins by Smads (e.g. in the absence of DNA-binding sites for ZEB in the reporter; Postigo et al., 2003), the presence of ZEB-binding sites in TGFβ/BMP-dependent genes could be crucial to concentrate endogenous ZEB and Smad proteins at target genes. It is therefore likely that, as with other proteins that augment Smad activity (e.g. OAZ, FAST), ZEB/δEF1 protein may only target a subset of genes in a fashion dictated by the distribution of their binding sites. For some Smad regulatory proteins, such as OAZ, the target is quite specific and may be restricted to the inhibitors of neural differentiation, Xenopus Vent-1 and Vent-2 genes (Hata et al., 2000).

In contrast, the several factors that inhibit Smad signaling (e.g. TGIF, Ski/SnoN, Evi-1) seem to do so in a less specific fashion—they do not seem to require direct binding to DNA to mediate their repressor effects, but rather they are recruited to target genes through their interaction with Smads (Kurokawa et al., 1998; Luo et al., 1999; Wotton et al., 1999; Izutsu et al., 2001). The exception to this pattern is ZEB-2/SIP1, which recognizes the same DNA-binding site as ZEB-1/δEF1 and would only block the activation of a subset of TGFβ/BMP-dependent genes—those containing ZEB-binding sites.

ZEB-2/SIP1 appears to bind ZEB sites with higher affinity than ZEB-1/δEF1, and it is also induced in response to TGFβ (Comijn et al., 2001; data not shown). It is tempting to speculate about the existence of a feedback mechanism between both ZEB proteins to limit the extent/duration of TGFβ signaling. In this model, induction of ZEB-2/SIP1 in response to TGFβ would in turn displace ZEB-1/δEF1 from the DNA sites and block transcription of TGFβ-responsive genes, shutting off the amplification loop created by ZEB-1/δEF1 and TGFβ. This mechanism would only target genes containing both ZEB and Smad-binding sites. The existence of such feedback is currently under investigation.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

Mv1Lu cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The following cell lines were obtained directly from investigators: 293T cells from Dr S.Korsmeyer (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA), HaCAT from Dr S.Dowdy (University of California, San Diego, CA) and HCT116 and HCT116/518 cells from Dr B.Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 12% fetal calf serum (Gibco-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). In selected experiments, cells were treated with the indicated amounts of recombinant TGFβ1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or BMP-2 (kind gift of Dr T.Celeste, Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA and R&D Systems). Stable clones in Mv1Lu cells were obtained by cotransfection of either pCMV-MCS, pCMV-MCS-EGFP-ZEB-1 or pCMV-EGFP-ZEB-2 (see below) (Clontech Labs) along with a plasmid encoding the neomycin resistance (pCIneo; Promega, Madison, WI).

Plasmid construction

3TP-lux, CMV5-Flag-Smad1, CS2-Flag-Smad2 and CMV-Flag-Smad3 were obtained from Dr J.Massagué (Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). p21, p15 and c-jun reporters, containing the TGFβ-responsive elements in these promoters fused to firefly luciferase, were obtained from Dr X.C.Wang (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC). Xenopus Vent-2-luciferase reporter was obtained from Dr C.Niehrs (Deutsches Krebforschungs zentrum, Heidelberg, Germany). A dominant-negative form of Smad3 (D470E) and constitutively active forms for ALK5 (T204D) and ALK6 (Q203D) were obtained from Dr K.Miyazono (Cancer Institute, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, Tokyo, Japan).

The different myc-tagged versions of ZEB proteins were constructed as follows. A XhoI–XbaI PCR fragment corresponding to the full-length human cDNA for ZEB-1/δEF1 was cloned into the corresponding sites of the CS2MT vector. A XbaI–EcoRV PCR fragment corresponding to the full-length human cDNA for ZEB-2/SIP1 was cloned into the XbaI–SnaBI sites of CS2MT. CS2MT-ZEB-1 (ΔSID) was cloned in two steps. First, a StuI–XbaI fragment corresponding to the amino acids 1–377 of ZEB-1/δEF1 was cloned into the corresponding sites of CS2MT. The resulting plasmid was cut with XbaI–SnaBI and a PCR fragment encoding from amino acid 456 to the stop codon at 1125 of human ZEB-1/δEF1 with identical sites was cloned. CS2MT-ZEB-2 (ΔSID) was also constructed in two steps. First, a XbaI–EcoRV PCR fragment encoding amino acids 1–422 of human ZEB-2/SIP1 was cloned into the XbaI/SnaBI sites of CS2MT. The 3′ primer also contained MluI/BlgII sites where a MluI–BglII PCR fragment encoding amino acids 504 to the stop codon at 1215 of ZEB-2/SIP1 were cloned. The remainder of the constructs shown in Figure 2E correspond to the regions 1, 2, CtBP-interacting domain (CID) and 3 as described in Postigo and Dean (1999a, 2000). From the original Flag-tagged ZEB constructs described in those references, CS2MT derivatives were made as follows. For ZEB-1/δEF1 myc-tagged constructs, the different regions were amplified by PCR with primers containing XhoI/EcoRV ends and cloned into the XhoI/SnaBI sites of CS2MT. In the case of ZEB-2/SIP1 regions, we used oligos containing XbaI/EcoRV sites and the corresponding PCR fragments were then cloned into the XbaI/SnaBI sites of CS2MT. pCMV-MCS-EGFP-ZEB-1 and pCMV-EGFP-ZEB-2 were obtained by cloning a XhoI–Not fragment from the corresponding pCI-Flag-neo version of ZEB-1/δEF1 and ZEB-2/SIP1 (Postigo and Dean, 1997, 2000) into the corresponding sites of pCMV-MCS-EGFP (Clontech Lab).

Transfections

Cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method or with Superfectin reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as described (Postigo and Dean, 2000). For luciferase assays, 5–12 h after transfection, cells were washed and activated with the indicated amounts of TGFβ1 or BMP-2. Twenty-four hours later, luciferase activity was assessed. As an internal control for transfection, cells were cotransfected with SV40 β-gal (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), and values were determined using a luminescent β-galactosidase detection Kit II® (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). Transcriptional assays using a chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) reporter gene were performed as described previously (Postigo and Dean, 2000). In the experiments where antisense oligonucleotides were used, cells were transfected with 1 µM each oligo using Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After 18 h, cells were treated with the indicated amount of TGFβ. Control oligo: TCTGCGGCCTGTGTCAAGCTA; antisense ZEB-1 (oligo A) CAAGGGTTCTTCCTGGACAG; antisense ZEB-1 (oligo B): CCCCYTCAAAGCTTTTGTCC.

Protein co-immunoprecipitations and western blot assays

Immunoprecipitation and western blots were performed as described previously (Postigo and Dean, 2000). Where indicated, lysates were immunoprecipitated with agarose-conjugated anti-Flag M2 (Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO), anti-Gal4-DBD, anti-ZEB-1 (ZEB C-20) and anti-myc 9E10 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies. Also where indicated, 15% of the lysate was directly loaded into the gel as input control for direct western blotting. The following HRP-conjugated antibodies were used for western blotting: Gal4-DBD polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-LexA polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-Flag M2 mAb (Sigma Chemicals) or anti-myc 9E10 mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Anti-Smad2/Smad3 antibody was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology.

Osteogenic differentiation assays

Twenty thousand C2C12 cells were transfected in a 6-well plate with 5 µg of empty vector, ZEB-1, ZEB-2 or their corresponding ΔSID mutants using Effectene (Qiagen). After 5 h, cells were washed and treated with the indicated amount of BMP-2 (Genetics Institute) and cultured for 3–5 days. Histochemical analysis of ALP activity was assessed using a kit from Sigma. After the reaction had developed, the number of ALP-positive cells was counted using a phase contrast microscope.

Flow cytometry analysis

Mv1Lu cells were cotransfected with 20 µg of either vector alone or either CS2MT-ZEB-1 or CS2MT-ZEB-1 (ΔSID) and 1 µg of a EGFP expression vector and treated with the indicated amounts of TGFβ1. The microtubule inhibitor nocodazole (Sigma Chemicals) was added at 75 ng/ml for 24 h prior to the experiment to induce a G2/M arrest. Forty-eight hours after transfection, at least 10 000 EGFP-positive cells were collected, and the cell cycle profile was determined as described previously (Zhang et al., 2000).

Proliferation assays

Stable clones derived from Mv1Lu cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 in 12-well culture plates, treated with the indicated amount of TGFβ1 and incubated for 36 h. During the last 8–12 h, cells were incubated with 1 µCi/well [3H]thymidine (ICN Pharmaceuticals). After that period, cells were washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 10% Tris–HCl for 1 h and solubilized in 0.5 M NaOH for 30 min. Lysates were then neutralized with HCl, and [3H]thymidine uptake quantified in a liquid scintillation β-counter.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Drs T.Celeste, S.Dowdy, S.J.Korsmeyer, J.Massagué, K.Miyazono, C.Niehrs, B.Vogelstein and X.C.Wang for providing valuable constructs, cytokines and cell lines. A.A.P. is a recipient of a Career Development Award (Special Fellow) from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (formerly Leukemia Society of America).

References

- Attisano L. and Wrana,J.L. (2000) Smads as transcriptional modulators. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry F.B., Miura,Y. Mihara,K., Kaspar,P., Sakata,N., Hashimoto-Tamaoki,T. and Tamaoki,T. (2001) Positive and negative regulation of myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells by isoforms of the multiple homeodomain zinc finger transcription factor ATBF1. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 25057–25065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T., Jung,A., Hlubek,F., Lohberg,C., Meiler,J., Suchy,U. and Kirchner,T. (1999) Negative regulation of CD4 expression in T cells by the transcriptional repressor ZEB. Int. Immunol., 11, 1701–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broihier H.T, Moore,L.A., Van Doren,M., Newman,S. and Lehmann,R. (1998) zfh-1 is required for germ cell migration and gonadal mesoderm development in Drosophila. Development, 125, 655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacheux V., Dastot-Le Moal,F., Kaariainen,H., Bondurand,N., Rintala,R., Boissier,B., Wilson,M., Mowat,D. and Goossens,M. (2001) Loss-of-function mutations in SIP1 (Smad interacting protein 1) result in a syndromic Hirschsprung disease. Hum. Mol. Genet., 10, 1503–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain E.M. and Sanders,M.M. (1999) Identification of the novel player δEF1 in estrogen transcriptional cascades. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 3600–3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Weisberg,E., Fridmacher,V., Watanabe,M., Naco,G. and Whitman,M. (1997) Smad4 and FAST-1 in the assembly of activin-responsive factor. Nature, 389, 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnadurai G. (2002) CtBP and unconventional transcriptional corepressor in development and oncogenesis. Mol. Cell, 9, 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian J.L. and Nakayama,T. (1999) Can’t get no SMADisatisfaction: Smad proteins as positive and negative regulators of TGFβ family signals. BioEssays, 21, 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijn J., Berx,G., Vermassen,P., Verschueren,K., van Grunsven,L., Bruyneel,E., Mareel,M., Huylebroeck,D. and van Roy,F. (2001) The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol. Cell, 7, 1267–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daluiski A., Engstrand,T., Bahamonde,M.E., Gamer,L.W., Agius,E., Stevenson,S.L., Cox,K., Rosen,V. and Lyons,K.M. (2001) Bone morphogenetic protein-3 is a negative regulator of bone density. Nat. Genet., 27, 84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Caestecker M.P., Piek,E. and Roberts,A.B. (2000) Role of transforming growth factor-β signaling in cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst., 2, 1388–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillner N.B. and Sanders,M.M. (2002) The zinc finger/homeodomain protein deltaEF1 mediates estrogen-specific induction of the ovalbumin gene. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol., 192, 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisakei A., Kurosda,H. Fukui,A. and Asashima,M. (2000) XSIP1, a member of the two handed zinc finger proteins induced anterior neural markers in Xenopus laevis animal cap. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 271, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontemaggi G., Gurtner,A., Strano,S., Higashi,Y., Sacchi,A., Piaggio,G. and Blandino,G. (2001) The transcriptional repressor ZEB regulates p73 expression at the crossroad between proliferation and differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 8461–8470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini M.E., Lai,Z.C. and Rubin,G.M. (1991) The Drosophila zfh-1 and zfh-2 genes encode novel proteins containing both zinc-finger and homeodomain motifs. Mech. Dev., 34, 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetta T., Ruezinsky,D. and Kadesch,T. (1994) Displacement of an E-box-binding repressor by basic helix–loop–helix proteins: implications for B-cell specificity of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 6153–6163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto D., Yagi,K., Inoue,H., Iwamoto,I., Kawabata,M., Miyazono,K. and Kato,M. (1998) A single missense mutant of Smad3 inhibits activation of both Smad2 and Smad3 and has a dominant negative effect on TGFβ signals. FEBS Lett., 430, 201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire J.M. and Romeo,P.H. (1999) T-cell expression of the human GATA-3 gene is regulated by a non-lineage-specific silencer. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 6567–6578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grooteclaes M.L. and Frisch,S.M. (2000) Evidence for a function of CtBP in epithelial gene regulation and anoikis. Oncogene, 19, 3823–3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata A., Seoane,J., Lagna,G., Montalvo,E., Hemmati-Brivanlou,A. and Massagué,J. (2000) OAZ uses distinct DNA- and protein-binding zinc fingers in separate BMP–Smad and Olf signaling pathways Cell, 100, 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X., Liu,X., Ansari,D.O. and Lodish,H.F. (1998) Synergistic cooperation of TFE3 and smad proteins in TGF-β-induced transcription of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene. Genes Dev., 12, 3084–3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izutsu K., Kurokawa,M., Imai,Y., Maki,K., Mitani,K. and Hirai,H. (2001) The corepressor CtBP interacts with Evi-1 to repress transforming growth factor β signaling. Blood, 97, 2815–2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C.M., Lyons,K.M., Lapan,P.M., Wright,C.V.E. and Hogan,B.L.M. (1992) DVR-4 (Bone morphogenetic protein-4) as a posterior-ventralizing factor in Xenopus mesoderm induction. Development, 115, 639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar P., Dvorakova,M., Kralova,J., Pajer,P., Kozmik,Z. and. Dvorak,M. (1999) Myb-interacting protein, ATBF1, represses transcriptional activity of Myb oncoprotein. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 14422–14428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri T. et al. (1994) Bone morphogenetic protein-2 converts the differentiation pathway of C2C12 myoblasts into the osteoblast lineage. J. Cell Biol., 127, 4569–4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley D.M. (2001) Genetic control of bone and joint formation. Novartis Found. Symp., 232, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen P.J., Sistonen,L., Bravo,R. and Alitalo,K. (1991) Immediate early gene responses of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and NMuMG epithelial cells to TGF β-1. Growth Factors, 5, 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M., Mitani,K., Irie,K., Matsuyama,T., Takahashi,T., Chiba,S., Yazaki,Y., Matsumoto,K. and Hirai,H. (1998) The oncoprotein Evi-1 represses TGF-β signalling by inhibiting Smad3. Nature, 394, 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe E., Silvestri,C., Hoodless,P.A., Wrana,J.L. and Attisano,L. (1998) Smad2 and Smad3 positively and negatively regulate TGFβ-dependent transcription through the forkhead DNA-binding protein FAST-2. Mol. Cell, 2, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Z.C., Fortini,M.E. and Rubin,G.M. (1991) The embryonic expression patterns of zfh-1 and zfh-2, two Drosophila genes encoding novel zinc-finger homeodomain proteins. Mech. Dev., 34, 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Z.C., Rushton,E., Bate,M. and Rubin,G.M. (1993) Loss of function of the Drosophila zfh-1 gene results in abnormal development of mesodermally derived tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 4122–4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarova D.L., Bordonaro,M. and Sartorelli,A.C. (2001) Transcriptional regulation of the vitamin D3 receptor gene by ZEB. Cell Growth Differ., 12, 319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerchner W., Latinkic,B.V., Remacle,J.E., Huylebroeck,D. and Smith,J.C. (2000) Region-specific activation of the Xenopus brachyury promoter involves active repression in ectoderm and endoderm: a study using transgenic frog embryos. Development, 127, 2729–2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K., Stroschein,S.L., Wang,W., Chen,D., Martens,E., Zhou,S. and Zhou,Q. (1999) The Ski oncoprotein interacts with the Smad proteins to repress TGFβ signaling. Genes Dev., 13, 2196–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. and Chen,Y.G. (2000) Controlling TGFβ signaling. Genes Dev., 14, 627–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. and Wotton,D. (2000) Transcriptional control by the TGFβ/Smad signaling system. EMBO J., 19, 1745–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J., Blain,S.W. and Lo,R.S. (2000) TGFβ signaling in growth control, cancer and heritable disorders. Cell, 103, 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura Y., Tam,T., Ido,A., Morinaga,T., Miki,T., Hashimoto,T. and Tamaoki,T. (1995) Cloning and characterization of an ATBF1 isoform that expresses in a neuronal differentiation-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 26840–26880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K., Kusanagi,K. and Inoue,H. (2001) Divergence and convergence of TGF-β/BMP signaling. J. Cell Physiol., 187, 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D., Precht,P., Balakir,R. and Horton,W.E.,Jr (2000) The transcription factor δEF1 is inversely expressed with type II collagen mRNA and can repress Col2a1 promoter activity in transfected chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 3610–3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse M. and Egner,H.J. (1984) Can nocodazole, an inhibitor of microtubule formation, be used to synchronize mammalian cells? Accumulation of cells in mitosis studied by two parametric flow cytometry using acridine orange and by DNA distribution analysis. Cell. Tissue Kinet., 17, 13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo A.A and Dean,D.C. (1997) ZEB, a vertebrate homolog of Drosophila Zfh-1, is a negative regulator of muscle differentiation. EMBO J., 16, 3935–3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo A.A. and Dean,D.C. (1999a) ZEB represses transcription through interaction with the corepressor CtBP. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 6683–6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo A.A. and Dean,D.C. (1999b) Independent repressor domains in ZEB regulate muscle and T-cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 7961–7971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo A.A. and Dean,D.C. (2000) Differential expression and function of members of the zfh-1 family of zinc finger/homeodomain repressors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 6391–6396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo A.A., Sheppard,A.M., Mucenski,M.L. and Dean,D.C. (1997) c-myb and ets factors synergize to overcome transcriptional repression by ZEB. EMBO J., 16, 3924–3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo A.A., Ward,E., Skeath,J.B. and Dean,D.C. (1999) zfh-1, the Drosophila homologue of ZEB, is a transcriptional repressor that regulates somatic myogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 7255–7263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo A.A., Depp,J.L., Taylor,J.T. and Kroll,K.L. (2003) Regulation of Smad signaling through a differential recruitment of coactivators and corepressors by ZEB proteins. EMBO J., 22, 2453–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remacle J.E., Kraft,H., Lerchner,W., Wuytens,G., Collart.,C., Verschueren,K., Smith,J.C. and Huylebroeck,D. (1999) New mode of DNA binding of multi-zinc finger transcription factors: δEF1 family members bind with two hands to two target sites. EMBO J., 18, 5073–5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekido R., Murai,K., Kamachi,Y. and Kondoh,H. (1997) Two mechanisms in the action of repressor δEF1: binding site competition with an activator and active repression. Genes Cells, 2, 771–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Wang,Y.F., Jayaraman,L., Yang,H., Massagué,J. and Pavletich,N. (1998) Crystal structure of a Smad MH1 domain bound to DNA. Insights on DNA-binding in TGFβ signaling. Cell, 94, 585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Liu,X., Eaton,E.N., Lane,W.S., Lodish,H.F. and Weinberg,R.A. (1999) Interaction of the Ski oncoprotein with Smad3 regulates TGF-β signaling. Mol. Cell, 4, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi T., Moribe,H., Kondoh,H. and Higashi,Y. (1998) δEF1, a zinc finger and homeodomain transcription factor, is required for skeleton patterning in multiple lineages. Development, 125, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P., Miyazono,K. and Heldin,C.H. (2000) Signaling inputs converge on nuclear effectors in TGFβ signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci., 25, 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terraz C., Toman,D., Delauche,M., Ronco,P. and Rossert,J.A. (2001) δEF1 binds to a far-upstream sequence of the pro α1(I) collagen gene and represses its expression in osteoblasts. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 37011–37019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylzanowski P., Verschueren,K., Huylebroeck,D. and Luyten,F.P. (2001) Smad-interacting protein 1 is a repressor of liver/bone/kidney alkaline phosphatase transcription in bone morphogenetic protein-induced osteogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 40001–40007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren K. et al. (1999) SIP1, a novel zinc finger/homeodomain repressor interacts with Smad proteins and bind to 5′-CACCT sequences in candidate target genes. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 20489–20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamatsu N. et al. (2001) Mutations in SIP1, encoding Smad interacting protein-1, cause a form of Hirschsprung disease. Nat. Genet., 27, 369–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Mariani,F.V., Harland,R.M. and Luo,K. (2000) Ski represses bone morphogenic protein signaling in Xenopus and mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 14394–14399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T.M., Moolten,D., Burlein,J., Romano,J., Bhaerman,R., Godillot,A., Mellon,M., Rauscher,F.J. and Kant,J.A. (1991) Identification of a zinc finger protein that inhibits IL-2 gene expression. Science, 254, 1791–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton D., Lo,R.S., Lee,S. and Massagué,J. (1999) A Smad transcriptional corepressor. Cell, 97, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawel L., Dai,J.L., Buckhautls,P., Zhou,S., Kinzler,K.W., Bogelstein,B. and Kern,S.E. (1998) Human Smad3 and Smad4 are sequence-specific transcription factors. Mol. Cell, 1, 611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.S., Gavin,M., Dahiya,A., Postigo,A.A., Ma,D., Luo,R.X., Harbour,J.W. and Dean,D.C. (2000) Exit from G1 and S phase of the cell cycle is regulated by repressor complexes containing HDAC-Rb-hSWI/SNF and Rb-hSWI/SNF. Cell, 101, 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Feng,X.H. and Derynck,R. (1998) Smad3 and Smad4 cooperate with c-Jun/c-Fos to mediate TGF-β-induced transcription. Nature, 394, 909–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweier C., Albrecht,B., Mitulla,B., Behrens,R., Beese,M., Gillessen-Kaesbach,G., Rott,H.D. and Rauch,A. (2002) ‘Mowat–Wilson’ syndrome with and without Hirschsprung disease is a distinct, recognizable multiple congenital anomalies–mental retardation syndrome caused by mutations in the zinc finger homeo box 1B gene. Am. J. Med. Genet., 108, 177–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]