Abstract

Inherited metabolic disorders that affect the central nervous system typically result in pathology throughout the brain; thus, gene therapy strategies need to achieve widespread delivery. We previously found that although intraventricular injection of the neonatal mouse brain with adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (AAV2) results in dispersed gene delivery, many brain structures were poorly transduced. This limitation may be overcome by using different AAV serotypes because the capsid proteins use different cellular receptors for entry, which may allow enhanced global targeting of the brain. We tested this with AAV1 and AAV5 vectors. AAV5 showed very limited brain transduction after neonatal injection, even though it has different transduction patterns than AAV2 in adult brain injections. In contrast, AAV1 vectors, which have not been tested in the brain, showed robust widespread transduction. Complementary patterns of transduction between AAV1 and AAV2 were established and maintained in the adult brain after neonatal injection. In the majority of structures, AAV1 transduced many more cells than AAV2. Both vectors transduced mostly neurons, indicating that differential expression of receptors on the surfaces of neurons occurs in the developing brain. The number of cells positive for a vector-encoded secreted enzyme (β-glucuronidase) was notably greater and more widespread in AAV1-injected brains. A comprehensive analysis of AAV1-treated brains from β-glucuronidase-deficient mice (mucopolysaccharidosis type VII) showed complete reversal of pathology in all areas of the brain for at least 1 year, demonstrating that the combination of this serotype and experimental strategy is therapeutically effective for treating global neurometabolic disorders.

Lysosomal storage diseases are inherited metabolic disorders characterized by mutations in genes encoding acid hydrolases (23). The loss of enzyme activity results in cell dysfunction due to accumulation of undegraded substrates in the lysosomal compartment. Most of these diseases have global storage lesions in the central nervous system (CNS) that result in progressive neurodegeneration and mental retardation. The collective frequency of all of the lysosomal storage diseases is approximately 1 in 5,000 live births, which represents about 20% of single-gene disorders that affect the brain (22, 31).

Treatment strategies for the global pathology in the brain must include widespread gene delivery so that cellular “enzyme pumps” can become established throughout the CNS. These pumps would then distribute the enzyme to nontransduced areas by multiple mechanisms, such as secretion and uptake by distal cells (37), axonal transport (26), and migrating progenitor cells (26, 35). We recently showed that widespread gene delivery can be achieved by injecting an adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) vector directly into the cerebral lateral ventricles at birth, and allowing the cerebrospinal fluid to deliver the virus throughout the CNS (25). However, many areas of the brain did not show substantial transduction with this experimental strategy. Regional differences in transduction may be due to restricted distribution of attachment receptors for AAV2 in the developing brain. More efficient transduction of the brain may be achieved by using a different serotype vector that targets more ubiquitous cell surface receptors. Although the cell surface receptor for AAV1 has not yet been identified, this serotype is a candidate for improved global transduction because it was shown to be a superior gene delivery vehicle in the muscle and liver compared to other AAV serotypes, as well as a good transducer of the retina (2, 11, 27). Despite these promising results, AAV1 has not been investigated in the brain.

In the present study, we injected AAV1 into the cerebral lateral ventricles of neonatal mice to determine whether this serotype can overcome the limitations observed with AAV2 and target different brain structures. We also examined the ability of an AAV1 vector expressing β-glucuronidase (GUSB) to reverse the global neuropathology present in mice with mucopolysaccharidosis type VII (MPS VII), a lysosomal storage disease resulting from mutations in GUSB. Murine MPS VII is a model system for lysosomal storage disorders because GUSB has features similar to most lysosomal enzymes and animal models for MPS VII have the same phenotype as the human disease (7, 21, 30, 34, 37, 38). The present study demonstrates that complementary patterns of transduction exist in the brain between AAV1 and AAV2 and that AAV1 transduced many more structures. The increased global targeting of AAV1 provided the necessary platform for enzyme pumps to correct storage lesions in gray and white matter, as well as epithelial structures of the brain, for at least 1 year after vector injection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production and intraventricular injection of AAV vectors.

The detailed construction of the recombinant AAV genome used in the present study was reported elsewhere (25). The recombinant genome contained AAV2 inverted terminal repeats that flanked three cassettes: the 2.6-kb human GUSB promoter and cDNA (HβH), the 0.4-kb simian virus 40 splice donor-acceptor and poly(A) sequences, and a 1.4-kb stuffer sequence to bring the genome size to that of wild-type AAV (4.7 kb). The recombinant genome was cross-packaged into AAV1 (AAV1-HβH) or AAV5 (AAV5-HβH) virions by utilizing a chimeric AAV2Rep/AAV1Cap or AAV2Rep/AAV5Cap plasmid during the triple-transfection procedure (20, 43). The packaging, purification, and titering were performed by the Institute for Human Gene Therapy at the University of Pennsylvania. Both viral vectors had an injection titer of 4.5 × 1012 genomic equivalents/ml, as determined by PCR of the simian virus 40 poly(A) sequence (20, 25). On the day of birth (P0.5), normal C3H/HeOuJ or MPS VII neonates were cryoanesthetized and injected with 2 μl of viral vector into each cerebral lateral ventricle with a finely drawn glass micropipette as described previously (25, 35). A total of 1.8 × 1010 genomic equivalents (4 μl) was injected into each mouse brain.

Preparation of brain.

All treatments of mice were approved by, and carried out according to the guidelines of, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Normal mice were sacrificed at either 1 month (n = 4) or 12 months (n = 4) postinjection (p.i.), and MPS VII mice were sacrificed at 12 months (n = 4) p.i. On the day of sacrifice, mice were anesthetized and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline, followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). Brains were then dissected from the skull and postfixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. For enzyme histochemistry, in situ hybridization, and immunofluorescence, brains were cryoprotected overnight in 30% sucrose at 4°C and then frozen on dry ice in 100% OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, Calif.). Coronal serial sections were cut at 20-μm thickness, mounted onto glass slides, and stored at −20°C. For histopathology studies, brains were instead embedded in JB4 resin, sectioned at 1 μm, and stained with 5% toluidine blue (42).

Enzyme histochemistry.

Frozen tissue sections were assayed for GUSB enzymatic activity by using a naphthol-AS-BI-β-d-glucuronide substrate (42). The very low levels of endogenous GUSB in the brains of C3H/HeOuJ mice were heat inactivated as reported elsewhere (10, 26).

In situ hybridization.

The nonradioactive digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe used to detect AAV vector-encoded human GUSB mRNA was generated as reported earlier (25). To determine the overall expression pattern, in situ hybridization-positive cells were detected by colorimetric staining via an alkaline phosphatase-mediated BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate)-nitroblue tetrazolium reaction (4, 25, 26). To determine the cell-type transduced by AAV1-HβH, fluorescent in situ hybridization was performed by using the tyramide signal amplification cyanine 3 system (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.), followed by immunofluorescence with a polyclonal antibody against neuron-specific enolase (NSE; Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.).

RESULTS

AAV1-HβH and AAV5-HβH were injected into the cerebral lateral ventricles of neonatal mice, and the resulting transduction pattern was compared to the AAV2-HβH intraventricular injection data from a recent report by our laboratory (25). The recombinant genome, the titer method (genome equivalents), the injection volume, and the experimental conditions for in situ hybridization and enzyme histochemistry were all identical to those used in the AAV2 study. This ensured that any detected differences in transduction were due to differences in the proteins that compose the virion capsids. The AAV5 vector resulted in very limited transduction, which was restricted mostly to the choroid plexus and ependymal cells (data not shown; D. J. Watson, M. A. Passini, and J. H. Wolfe, unpublished data). In contrast, AAV1 produced a robust and extensive pattern of transduction throughout the brain.

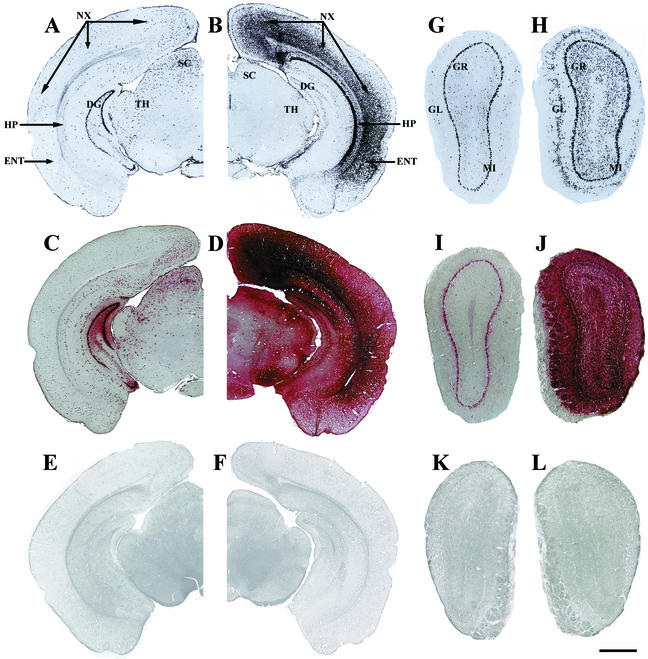

AAV1 showed complementary patterns of transduction in many structures of the brain compared to AAV2 (Fig. 1). AAV1-HβH transduced many more cells in the neocortex, the entorhinal cortex, and the CA1-CA3 areas of the hippocampus compared to AAV2-HβH (Fig. 1A to D). However, AAV1 transduced fewer cells in the superior colliculus, dentate gyrus, and thalamus compared to AAV2. Another example of complementary transduction was seen in the olfactory bulb (Fig. 1G to J). A large number of cells were transduced by AAV1 in the granule and glomerular layers, whereas few cells were transduced with AAV2. The efficient transduction of the mitral cell layer by both AAV1 and AAV2 demonstrated that similar patterns of transduction also occurred in some cell layers of the brain.

FIG. 1.

Complementary patterns of transduction after intraventricular injection of normal neonatal mice with AAV1-HβH or AAV2-HβH at 1 month p.i. Expression of virally encoded mRNA was detected by in situ hybridization with an antisense riboprobe against the human GUSB cDNA (A, B, G, and H), and biologically active enzyme was detected by histochemistry (C, D, I, and J). The AAV2 transduction patterns shown here (A, C, G, and I) were previously published (25) and are presented as a direct comparison to AAV1. (A) A section through the caudal forebrain-rostral midbrain showed AAV2 transduction in the neocortex, entorhinal cortex, superior colliculus, and dentate gyrus and in the thalamus and pretectal nucleus. (B) In comparison, AAV1 produced substantially higher numbers of in situ hybridization-positive cells in the CA1 to CA3 pyramidal and oriens cell layers of the hippocampus and in the neocortex and entorhinal cortex but produced smaller numbers of in situ hybridization-positive cells in the dentate gyrus, superior colliculus, and thalamus and pretectal nucleus. (C) Enzyme-positive cells were relatively confined to transduced cells in AAV2-injected brains. (D) In contrast, there was enzyme spread throughout the entire brain with AAV1. (E and F) The uninjected, normal control brain was not positive for GUSB activity in the absence (E) or presence (F) of heat inactivation. (G to J) Complementary patterns of transduction also occurred in other regions of the brain, such as the olfactory bulb. (G and I) With AAV2-HβH, transduction and enzymatic activity were detected mostly in the mitral cell layer. (H) In contrast, AAV1 produced robust transduction in the mitral, glomerular, and granule cell layers throughout the entire olfactory bulb. (J) This increase in transduction resulted in large amounts of biologically active enzyme in all laminar layers of the olfactory bulb. (K and L) The uninjected, normal control olfactory bulb did not show GUSB activity in the absence (K) or presence (L) of heat inactivation. Abbreviations: DG, dentate gyrus; ENT, entorhinal cortex; GL, glomerular cell layer; GR, granule cell layer; HP, CA1 to CA3 areas of the hippocampus; MI, mitral cell layer; NX, neocortex; SC, superior colliculus; TH, thalamus and pretectal nucleus. Bar: 1,000 μm (A to D) or 500 μm (E to H).

Another major difference between the two serotype vectors was the number of enzyme-positive cells in the brain after intraventricular injection. In brains injected with AAV1, enzymatic activity was present in all areas of the brain, regardless of whether a given structure was transduced or not by the viral vector (Fig. 1B, D, H, and J). This result contrasted with the AAV2 vector-injected brains, in which the number of enzyme-positive cells was approximately similar to the number of in situ hybridization-positive cells with some localized spread of secreted enzyme (1A, C, G, and I).

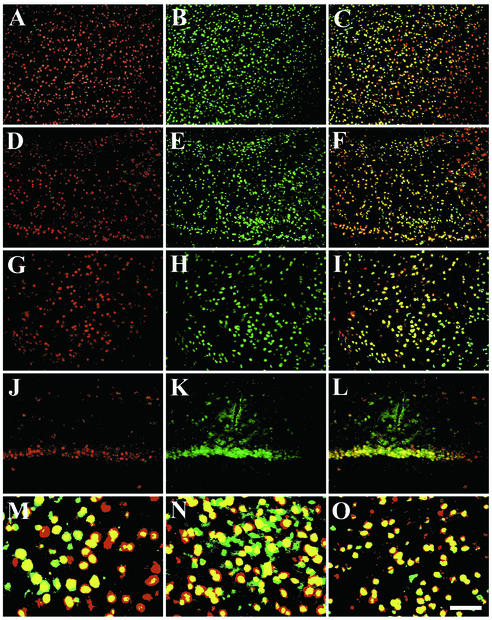

We combined fluorescent in situ hybridization with immunofluorescence to determine the cell type transduced by AAV1. In every gray-matter structure tested, the majority of the AAV1 vector-expressing cells colocalized with the neuron-specific marker NSE (Fig. 2). In contrast, AAV1 did not colocalize with astrocyte-specific (glial fibrillary acidic protein) or oligodendrocyte-specific (proteolipid protein) antibody markers (data not shown). This preference for neuronal transduction by AAV1 is also a property of AAV2 vectors in the mammalian brain (5).

FIG. 2.

AAV1-HβH is a neurotropic vector. Fluorescent in situ hybridization with the human GUSB riboprobe (red signal) (A, D, G, and J), immunofluorescence against neuron-specific enolase (green signal) (B, E, H, and K), and program overlay (yellow signal) (C, F, I, and L to O). The neocortex (A to C and M), entorhinal cortex (D to F and N), striatum (G to I and O), and CA1 cell layer of the hippocampus (J to L) of normal mice at 1 month p.i. Bar: 200 μm (A to L) or 50 μm (M to O).

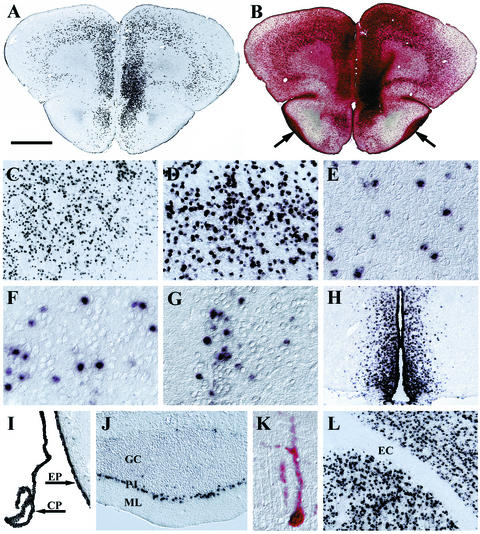

The widespread transduction pattern achieved by AAV1-HβH was maintained for at least 1 year after viral administration, supporting previous reports that the human GUSB promoter is capable of long-term expression after somatic gene transfer to the CNS (25, 26). As illustrated by the rostral forebrain at 1 year p.i., bilateral intraventricular injections resulted in a symmetrical pattern of transduction and enzymatic activity throughout the dorsoventral and mediolateral axes (Fig. 3A and B). Similarly impressive, widespread and robust expression was detected in many other areas of the brain (Fig. 3C to L). In addition to gray matter, the ependyma and choroid plexus were also transduced by AAV1 (Fig. 3I, J). However, white-matter tracts in all areas of the brain were transduced very poorly, as illustrated by the in situ hybridization-negative external capsule in a field of surrounding in situ hybridization-positive gray matter (Fig. 3L). Nevertheless, the amount of enzyme secreted by the transduced cell population provided enzyme for uptake by cells of the white-matter tracts (Fig. 1B and D and 3A and B). The differences and similarities in transduction patterns between AAV1-HβH and AAV2-HβH are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 3.

Long-term, widespread transduction with AAV1-HβH in the brains of normal mice at 1 year p.i. as determined by in situ hybridization (A, C to J, and L) and enzyme histochemistry (B and K). (A) Transduction was observed throughout the rostral forebrain. (B) Enzyme-positive cells were detected in transduced sites and in regions not positive for GUSB mRNA, such as the myelinated lateral olfactory tracts (arrows). Other regions that maintained expression included the striatum (C), entorhinal cortex (D), inferior colliculus (E), amygdala (F), hypothalamus (G), third ventricle and the surrounding periventricular region (H), ependyma and choroid plexus (I), and the Purkinje cell layer of the cerebellum (J). (K) Histochemistry showed an enzyme-positive cell with Purkinje cell morphology. (L) None of the white-matter tracts were transduced, such as the external capsule. Abbreviations: CP, choroid plexus; EC, external capsule; EP, ependyma; GC, granule cell layer of the cerebellum; ML, molecular layer of the cerebellum; PJ, Purkinje cell layer. Bar: 1,000 μm (A and B), 500 μm (H), 250 μm (C, I, J, and L), 125 μm (D), or 60 μm (E to G and K).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the transduction patterns in CNS structures after intraventricular brain injection of AAV1-HβH or AAV2-HβH in neonatal micea

| Transduction type and structure | AAV1

|

AAV2

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mo | 12 mo | 1 mo | 12 mo | |

| Different transduction patterns | ||||

| CA1 to CA3, HP | ++++ | +++ | + | + |

| Dentate gyrusb | ++ | +/− | ++++ | + |

| Neocortex | ++++ | +++ | +++ | + |

| Entorhinal cortex | ++++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Septum | +++ | +++ | +/− | − |

| Striatum | ++++ | +++ | +/− | − |

| Superior colliculus | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| Thalamus | + | + | +++ | ++ |

| GR, OB | ++++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| GL, OB | +++ | ++ | + | +/− |

| Choroid plexus | +++ | ++ | +/− | − |

| Ependyma | +++ | +++ | − | − |

| Periventricle, 3rdV | ++++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Similar transduction patterns | ||||

| Amygdala | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Hypothalamus | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Piriform cortex | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Substantia nigra | + | + | +/− | +/− |

| Inferior colliculus | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Purkinje layer, CB | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Medulla oblongata | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Spinal cord | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Mitral layer, OB | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Olfactory tubercle | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Parasubiculum | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Subiculum | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| White matter | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− |

Results are based on the average number of in situ hybridization-positive cells in one hemisphere of a 20-μm brain section. Scale: ++++, ≥201 cells; +++, 101 to 200 cells; ++, 31 to 100 cells; +, 10 to 30 cells; +/−, 1 to 9 cells; −, no cells. Abbreviations: 3rdV, third ventricle; CB, cerebellum; GL, glomerular cell layer; GR, granule cell layer; HP, hippocampus; OB, olfactory bulb.

The substantial decrease in the number of GUSB-expressing cells for AAV2 is due to the normal turnover of dentate granule cells (25).

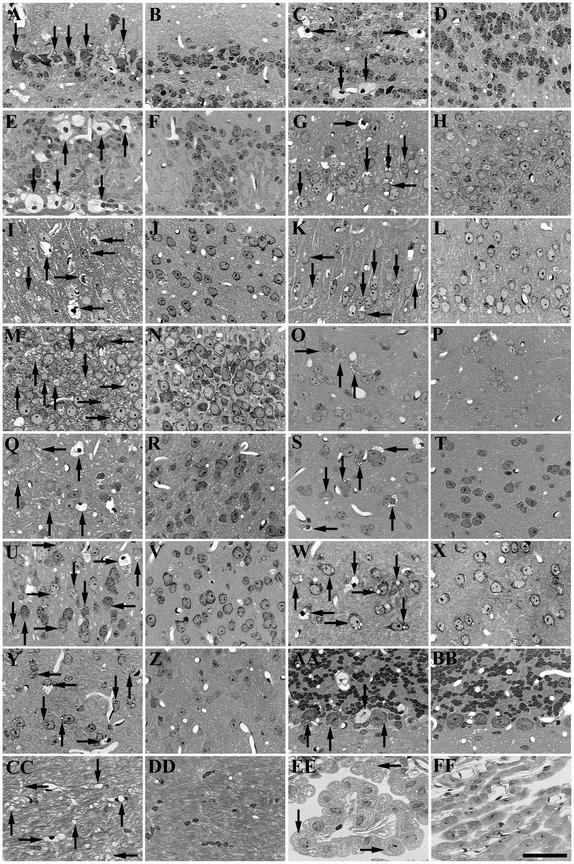

We tested the therapeutic efficacy of AAV1-HβH by injecting the viral vector into both cerebral lateral ventricles of newborn MPS VII mice. A comprehensive analysis of storage correction throughout the brain was done 1 year after injection because MPS VII, as well as other lysosomal storage diseases, are progressive neurodegenerative disorders that require continual enzyme replacement to prevent storage lesions. At 1 year p.i., the AAV1-HβH-treated mice had total reversal of storage lesions in neurons and glia of all structures. All gray-matter structures were corrected from the olfactory bulb to the cerebellum (Fig. 4A to BB). Even gray-matter structures that were not efficiently transduced, such as the thalamus and pretectal nucleus, were corrected. The reversal of pathology in the fimbria, external capsule, and corpus callosum (Fig. 4CC and DD) demonstrated that direct transduction of white matter is not required to rescue the glial cell population in myelinated tracts. Brain structures other than gray and white matter were also corrected, as demonstrated by the complete reversal of distended lysosomes in the choroid plexus (Fig. 4EE and FF).

FIG.4.

Reversal of storage lesions in MPS VII brains 1 year after intraventricular injection of AAV1-HβH. Uninjected MPS VII control (A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q, S, U, W, Y, AA, CC, and EE) and AAV1 vector-injected MPS VII (B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R, T, V, X, Z, BB, DD, and FF) brains. The mitral (A and B), granule (C and D), and glomerular (E and F) cell layers of the olfactory bulb; the piriform cortex (G and H); the neocortex (I and J); the entorhinal cortex (K and L); the CA3 pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus (M and N); the striatum (O and P); the hypothalamus (Q and R); the amygdala (S and T); the subiculum (U and V); the thalamus (W and X); the inferior colliculus (Y and Z); the Purkinje cell layer in the cerebellum (AA and BB); the external capsule (CC and DD); and the choroid plexus (EE and FF) are shown. Arrows point to representative neurons, glia, and microglia with lysosomal storage vacuoles. Bar: 25 μm.

DISCUSSION

Nine AAV serotypes that differ from one another by their capsid proteins have been identified (3, 12, 13, 19, 29, 43). Since the initial step in viral infection involves the binding of capsid proteins to cell surface receptors, the AAV serotypes differ in their ability to transduce organs. The differences in receptors used by AAV2 and AAV5 explains the differences in transduction patterns of these serotypes in the adult brain, lung, and muscle (1, 6, 14, 16, 20, 27, 36, 39, 44). Although the attachment receptors for the other AAV serotypes have not been identified, AAV4 shows a strong preference for transducing ependymal cells of the brain rather than the parenchyma (14).

In the present study we show that complementary patterns of transduction exist in the brain between AAV1-HβH and AAV2-HβH after intraventricular injections of neonatal mice. Robust AAV1 vector-expressing cells were detected in at least 10 structures of the brain that were poorly targeted by AAV2. At least three structures were transduced less efficiently by AAV1 than by AAV2 (Table 1). Because the genomic sequences and the titers of injected vectors were identical between the two serotypes, the differences in transduction must be due to variations in the capsid shells. While disparate patterns of transduction occurred in many structures, similar patterns were also evident. Since both vectors transduce mostly neurons, the neuronal populations of the developing brain must express distinct receptors in both overlapping and nonoverlapping domains.

The number of enzyme-positive cells in the brain with AAV1-HβH was far greater and more extensively distributed compared to AAV2-HβH. This increase in GUSB staining with AAV1 corresponded with the substantially higher number of in situ hybridization-positive cells. Because the amount of GUSB activity secreted from cells is proportional to mRNA expression (41), the brain is essentially flooded with GUSB by the large number of vector-positive cells transduced by AAV1. Furthermore, the efficient transduction of the ependyma and choroid plexus, which did not occur with the AAV2 vector, may allow GUSB to gain global access to the brain via enzyme secretion and flow through the cerebrospinal fluid. A continuous high level of GUSB expression has been shown to allow other modes of enzyme distribution, such as axonal transport or delivery by migrating progenitor cells, to contribute to the widespread enzyme-positive pattern in the brain (26).

AAV2 vectors produce enough enzyme to reverse storage lesions in the MPS VII mouse CNS but, when examined in detail, correction of pathology did not extend to all regions of the brain (8, 17, 18, 32, 33, 37). In the present study, we show that intraventricular injections of neonatal mice with AAV1-HβH results in the complete correction of storage lesions in all areas of the brain, including gray and white matter, as well as epithelial structures, for at least 1 year. Since the human GUSB promoter remains active over extended periods of time (25, 26), reversal of pathology should be indefinite. Furthermore, the high levels of enzyme produced by AAV1 were above those needed to improve cognitive and circadian rhythm dysfunctions in MPS VII mice (9, 18, 24, 28). There was no evidence of tumors in the normal or MPS VII brains at 1 year by gross morphological examination, as was observed in the liver after intravenous injection of neonatal mice with AAV2 (15).

The data indicate that AAV1 is a superior gene delivery vehicle in the CNS compared to the prototypic AAV2. The establishment of highly efficient enzyme pumps compensated for the lack of direct AAV1 transduction in some brain structures. The combination of a widely tropic and nontoxic vector with a long-term expression cassette fulfills the requirements needed for the treatment of global neurometabolic disorders. Gene transfer into the immature brain could improve the clinical outcome for patients with lysosomal storage diseases by blocking the early onset of pathology or by reducing the severity of the disease and long-term sequelae. In addition, AAV penetrates the brain parenchyma from the subarachnoid and ventricular spaces extensively when injected into the ventricles of neonates but is very limited in adult injections (25). Larger animal models of MPS VII and other lysosomal storage diseases, such as cat and dog models (40), should be useful in determining whether this experimental strategy can be scaled up to treat the large brain of humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Polesky, A. Radu, E. Cabacungan, M. Parente, S. Gallagher, J. Ming, L. Wang, G. Gao, and the IHGT Vector Core for their assistance.

This study was supported by NIH grants NS38690 and DK46637 to J.H.W. Support was also provided by NIH training grants for M.A.P. (DK07748) and D.J.W. (NS11024), by an NIH K08 award to C.H.V. (NS02032), and by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for D.J.L. and A.L.F.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alisky, J. M., S. M. Hughes, S. L. Sauter, D. Jolly, T. W. Dubensky, P. D. Staber, J. A. Chiorini, and B. L. Davidson. 2000. Transduction of murine cerebellar neurons with recombinant FIV and AAV5 vectors. Neuroreport 1:2669-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auricchio, A., G. Kobinger, V. Anand, M. Hildinger, E. O'Connor, A. M. Maguire, J. M. Wilson, and J. Bennett. 2001. Exchange of surface proteins impacts on viral vector cellular specificity and transduction characteristics: the retina as a model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:3075-3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bantel-Schaal, U., H. Delius, R. Schmidt, and H. Van Hausen. 1999. Human adeno-associated virus type 5 is only distantly related to other known primate helper-dependent parvovirus. J. Virol. 73:939-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barthel, L. K., and P. A. Raymond. 2000. In situ hybridization studies of retinal neurons. Methods Enzymol. 316:579-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartlett, J. S., R. J. Samulski, and T. J. McCown. 1998. Selective and rapid uptake of adeno-associated virus type 2 in brain. Hum. Gene Ther. 9:1181-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett, J. S., R. Wilcher, and R. J. Samulski. 2000. Infectious entry pathway of adeno-associated virus and adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 74:2777-2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkenmeier, E. H., M. T. Davisson, W. G. Bearner, R. E. Ganschow, C. A. Vogler, B. Gwynn, K. A. Lyford, L. M. Maltais, and C. J. Wawrzyniak. 1989. Murine mucopolysaccharidosis VII: characterization of a mouse with β-glucuronidase deficiency. J. Clin. Investig. 83:1258-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch, A., E. Perret, N. Desmaris, and J. M. Heard. 2000. Long-term and significant correction of brain lesions in adult mucopolysaccharidosis type VII mice using recombinant AAV vectors. Mol. Ther. 1:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks, A. I., C. S. Stein, S. M. Hughes, J. Heth, P. M. McCray, S. L. Sauter, J. C. Johnston, D. A. Cory-Slechta, H. J. Federoff, and B. L. Davidson. 2002. Functional correction of established central nervous system deficits in an animal model of lysosomal storage disease with feline immunodeficiency virus-based vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6216-6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casal, M. L., and J. H. Wolfe. 2001. In utero transplantation of fetal liver cells in the mucopolysaccharidosis type VII mouse results in low-level chimerism, but overexpression of β-glucuronidase can delay onset of clinical signs. Blood 97:1625-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao, H., Y. Liu, J. Rabinowitz, C. Li, R. J. Samulski, and C. E. Walsh. 2000. Several log increase in therapeutic transgene delivery by distinct adeno-associated viral serotype vectors. Mol. Ther. 2:619-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiorini, J. A., L. Yang, Y. Liu, B. Safer, and R. M. Kotin. 1997. Cloning of adeno-associated virus type-4 (AAV4) and generation of recombinant AAV4 particles. J. Virol. 71:6823-6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiorini, J. A., F. Kim, L. Yang, and R. M. Kotin. 1999. Cloning and characterizing of adeno-associated virus type-5. J. Virol. 73:1309-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson, B. L., C. S. Stein, J. A. Heth, I. Martins, R. M. Kotin, T. A. Derksen, J. Zabner, A. Ghodsi, and J. A. Chiorini. 2000. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3428-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donsante, A., C. Vogler, N. Muzyczka, J. M. Crawford, J. Barker, T. Flotte, M. Campbell-Thompson, T. Daly, and M. S. Sands. 2001. Observed incidence of tumorigenesis in long-term rodent studies of rAAV vectors. Gene Ther. 8:1343-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan, D., Z. Yan, Y. Yue, W. Ding, and J. F. Engelhardt. 2001. Enhancement of muscle gene delivery with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus type 5 correlates with myoblast differentiation. J. Virol. 75:7662-7671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliger, S., C. Elliger, C. Aguilar, N. Raju, and G. Watson. 1999. Elimination of lysosomal storage in brains of MPS VII mice treated with intrathecal administration of an adeno-associated virus vector. Gene Ther. 6:1175-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisella, W. A., L. H. O'Connor, C. A. Vogler, M. Roberts, S. Walkley, B. Levy, T. M. Daly, and M. S. Sands. 2001. Intracranial injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus improves cognitive function in a murine model of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Mol. Ther. 3:351-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao, G. P., M. R. Alivira, L. Wang, R. Calcedo, J. Johnston, and J. M. Wilson. 2002. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11854-11859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hildinger, M., A. Auricchio, G. P. Gao, L. Wang, N. Chirmule, and J. M. Wilson. 2001. Hybrid vectors based on adeno-associated virus serotypes 2 and 5 for muscle-directed gene transfer. J. Virol. 75:6199-6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy, B., N. Galvin, C. Vogler, E. H. Birkenmeier, and W. S. Sly. 1996. Neuropathology of murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Acta Neuropathol. 92:562-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meikle, P. J., J. J. Hopwood, A. E. Clague, and W. F. Carey. 1999. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA 20:249-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neufeld, E. F. 1991. Lysosomal storage diseases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 60:257-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connor, L. H., L. C. Erway, C. A. Vogler, W. S. Sly, A. Nicholes, J. Grubb, S. W. Holmberg, B. Levy, and M. S. Sands. 1998. Enzyme replacement therapy for murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII leads to improvements in behavior and auditory function. J. Clin. Investig. 101:1394-1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Passini, M. A., and J. H. Wolfe. 2001. Widespread gene delivery and structure-specific patterns of expression in the brain from an adeno-associated virus vector following intraventricular injections of neonatal mice. J. Virol. 75:12382-12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Passini, M. A., E. B. Lee, G. G. Heuer, and J. H. Wolfe. 2002. Distribution of a lysosomal enzyme in the adult brain by axonal transport and by cells of the rostral migratory stream. J. Neurosci. 22:6437-6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabinowitz, J. E., F. Rolling, C. Li, H. Conrath, W. Xiao, A. Xiao, and R. J. Samulski. 2002. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J. Virol. 76:791-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross, C. J., M. Ralph, and P. L. Chang. 2000. Somatic gene therapy for a neurodegenerative disease using microencapsulated recombinant cells. Exp. Neurol. 166:276-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutledge, E. A., C. L. Halbert, and D. W. Russell. 1998. Infectious clones and vectors derived from adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes other than AAV type 2. J. Virol. 72:309-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sando, G. N., and E. F. Neufeld. 1977. Recognition and receptor-mediated uptake of a lysosomal enzyme, alpha-l-iduronidase, by cultured human fibroblasts. Cell 12:619-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sciver, C. R., A. L. Beaudet, W. S. Sly, and D. Valle. 2001. Metabolic basis of inherited disease, 8th ed., p. 3369-3894. McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, N.Y.

- 32.Sferra, T. J., G. Qu, D. McNeely, R. Rennard, K. R. Clark, W. D. Lo, and P. R. Johnson. 2000. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated correction of lysosomal storage within the central nervous system of the adult mucopolysaccharidosis type VII mouse. Hum. Gene Ther. 11:507-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skorupa, A. F., K. J. Fisher, J. M. Wilson, M. K. Parente, and J. H. Wolfe. 1999. Sustained production of β-glucuronidase from localized sites after AAV vector gene transfer results in widespread distribution of enzyme and reversal of lysosomal storage lesions in a large volume of brain in mucopolysaccharidosis VII mice. Exp. Neurol. 160:17-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sly, W. S., B. A. Quinton, W. J. McAlister, and D. J. Rimoin. 1973. Beta glucuronidase deficiency: report of clinical, radiologic, and biochemical features of a new mucopolysaccharidosis. J. Pediatr. 82:249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder, E. Y., R. M. Taylor, and J. H. Wolfe. 1995. Neural progenitor cell engraftment corrects lysosomal storage throughout the MPS VII mouse brain. Nature 374:367-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Summerford, C., and R. J. Samulski. 1998. Membrane-associated heparin sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 72:1438-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor, R. M., and J. H. Wolfe. 1997. Decreased lysosomal storage in the adult MPS VII mouse brain in the vicinity of grafts of retroviral vector-corrected fibroblasts secreting high levels of β-glucuronidase. Nat. Med. 3:771-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogler, C., E. H. Birkenmeier, W. S. Sly, B. Levy, C. Pegors, J. W. Kyle, and W. G. Beamer. 1990. A murine model of mucopolysaccharidosis VII. Am. J. Pathol. 136:207-217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walters, R. W., S. M. P. Yi, S. Keshavjee, K. E. Brown, M. J. Welsh, J. A. Chiorini, and J. Zabner. 2001. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3 sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20610-20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watson, D. J., and J. H. Wolfe. 2002. Lentiviral vectors for gene transfer to the central nervous system: applications in lysosomal storage disease animal models, p. 383-403. In C. Machida (ed.), Viral vectors for gene therapy: methods and protocols. Humana Press, Inc., Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Wolfe, J. H., J. W. Kyle, M. S. Sands, W. S. Sly, D. G. Markowitz, and M. K. Parente. 1995. High levels of expression and export of β-glucuronidase from murine mucopolysaccharidosis VII cells corrected by a double-copy retrovirus vector. Gene Ther. 2:70-78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfe, J. H., and M. S. Sands. 1996. Murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII: a model for somatic gene therapy of the central nervous system, p. 263-274. In R. R. Lowenstein and L. W. Enquist (ed.), Protocols for gene transfer in neuroscience: towards gene therapy of neurological disorders. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 43.Xiao, W., N. Chirmule, S. C. Berta, B. McCullough, G. P. Gao, and J. M. Wilson. 1999. Gene therapy based on adeno-associated virus type 1. J. Virol. 73:3994-4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zabner, J., M. Seiler, R. Walters, R. Kotin, W. Fulgeras, B. L. Davidson, and J. A. Chiorini. 2000. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surface of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer. J. Virol. 74:3852-3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]