Abstract

The anaerobic soil bacterium Eubacterium barkeri catabolizes nicotinate to pyruvate and propionate via a unique fermentation. A full molecular characterization of nicotinate fermentation in this organism was accomplished by the following results: (i) A 23.2-kb DNA segment with a gene cluster encoding all nine enzymes was cloned and sequenced, (ii) two chiral intermediates were discovered, and (iii) three enzymes were found, completing the hitherto unknown part of the pathway. Nicotinate dehydrogenase, a (nonselenocysteine) selenium-containing four-subunit enzyme, is encoded by ndhF (FAD subunit), ndhS (2 x [2Fe-2S] subunit), and by the ndhL/ndhM genes. In contrast to all enzymes of the xanthine dehydrogenase family, the latter two encode a two-subunit molybdopterin protein. The 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase, catalyzing reduction of 6-hydroxynicotinate to 1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-6-oxonicotinate, was purified and shown to contain a covalently bound flavin cofactor, one [2Fe-2S]2+/1+ and two [4Fe-4S]2+/1+ clusters. Enamidase, a bifunctional Fe-Zn enzyme belonging to the amidohydrolase family, mediates hydrolysis of 1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-6-oxonicotinate to ammonia and (S)-2-formylglutarate. NADH-dependent reduction of the latter to (S)-2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate is catalyzed by a member of the 3-hydroxyisobutyrate/phosphogluconate dehydrogenase family. A [4Fe-4S]-containing serine dehydratase-like enzyme is predicted to form 2-methyleneglutarate. After the action of the coenzyme B12-dependent 2-methyleneglutarate mutase and 3-methylitaconate isomerase, an aconitase and isocitrate lyase family pair of enzymes, (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate dehydratase and lyase, completes the pathway. Genes corresponding to the first three enzymes of the E. barkeri nicotinate catabolism were identified in nine Proteobacteria.

Nicotinate (niacin, vitamin B3) is an important constituent of all living cells in the form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate). Cells contain NAD(P) concentrations of 0.1–1 mM (1), which supply nicotinate as a nitrogen, carbon, and energy source to a diverse set of dedicated nicotinate-catabolizing microorganisms (2). Nicotinate catabolism in all organisms starts with hydroxylation to 6-hydroxynicotinate by the well characterized and industrially used enzyme nicotinate dehydrogenase (3). Further catabolism depends on the availability of oxygen in the environment. In several aerobic organisms, such as Pseudomonads, 6-hydroxynicotinate is oxidatively decarboxylated to 2,5-dihydroxypyridine (4) or, in the unique case of Bacillus niacini, subjected to a second hydroxylation yielding 2,6-dihydroxynicotinate (5). Under microaerobic (6) or fermentative conditions (7), ferredoxin-dependent reduction to 1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-6-oxonicotinate (THON) is observed.

Work by Harary (8) and Stadtman (9) identified an anaerobic soil bacterium now called Eubacterium barkeri (order Clostridiales) that fermented nicotinate according to the following equation:

|

Cell extracts incubated with radioactively labeled nicotinate allowed a number of unusual intermediates to be identified (10, 11), and it became clear that the pathway was remarkably complex (see Fig. 1). Based on the identified intermediates, several anticipated enzymes were purified and characterized: nicotinate dehydrogenase (12), 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase (7), 2-methyleneglutarate mutase, and 3-methylitaconate isomerase (13, 14). These findings outlined the nicotinate fermentation pathway and placed the identified intermediates in an enzymatic framework.

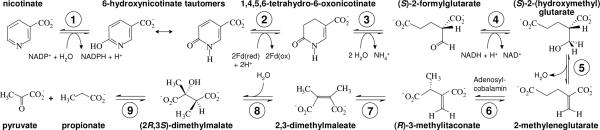

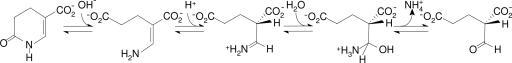

Fig. 1.

Nicotinate fermentation in E. barkeri. ➀, nicotinate dehydrogenase; ➁, 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase; ➂, enamidase; ➃, 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydrogenase; ➄, 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydratase; ➅, 2-methyleneglutarate mutase; ➆, (R)-3-methylitaconate isomerase; ➇, (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate dehydratase; ➈, (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate lyase.

The nicotinate dehydrogenase contains [2Fe-2S] clusters (15), FAD and molybdopterin cytosine dinucleotide (16), and has an unusual subunit composition [50, 37, 33, and 23 kDa (17)]. It has labile (nonselenocysteine) selenium (18) also identified in purine dehydrogenase from Clostridium purinolyticum and xanthine dehydrogenases from C. purinolyticum (19), Clostridium acidiurici (20), and E. barkeri (21). The selenium coordinates molybdenum (15) and is thought to be a selenido equivalent of the cyanolyzable sulfido-ligand (22) in the xanthine dehydrogenase family of enzymes. Studies in Marburg (23, 24) focused on the adenosylcobalamin-dependent carbon skeleton-rearranging enzyme 2-methyleneglutarate mutase and 3-methylitaconate isomerase. Genes encoding these two enzymes were cloned from a 3.7-kbp PstI-DNA fragment (24). The last two steps of the pathway have been characterized through partial purification of a labile (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate dehydratase and (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate lyase, and the stereochemical course was determined (25–28).

Despite the work described earlier, our understanding of nicotinate fermentation is still incomplete. Previously, 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase was reported to be an [Fe-S] protein, but no molecular characterization was performed. Although enzyme-catalyzed THON hydrolysis was detected (29), conversion of THON to 2-methyleneglutarate was not investigated. Here we report a full characterization of 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase and identify two nicotinate fermentation enzymes: a bifunctional hydrolase that converts THON to 2-formylglutarate (called enamidase) and 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydrogenase. Evidence is presented for the intermediacy of chiral 2-formylglutarate and 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate. The nucleotide sequence of a 23.2-kbp chromosomal DNA fragment of E. barkeri harboring all genes for the nicotinate fermentation enzymes has been determined. Gene clusters associated with nicotinate catabolism in other bacteria were identified with database searches.

Results and Discussion

The E. barkeri Nicotinate Gene Cluster.

Chromosomal DNA fragments of E. barkeri were cloned by using λ-ZAP-Express phage libraries (30) and Southern blot hybridization with digoxygenin-labeled probes derived from the known PstI fragment (24) (Fig. 2A). In conjunction with direct genomic sequencing (31) and SeeGene DNA walking (32), a contig of 23,202 bp (52.8% GC) was assembled. Identification of genes and startcodons used for their translational initiation was unambiguous: Near consensus GGAGG Shine–Dalgarno sequences were present at 7 ± 3 nucleotides from the startcodons (18 × ATG, 2 × GTG, and 1 × TTG). Predicted and experimental N-terminal amino acid sequences of 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase and enamidase reported here were in full agreement, as were those of the nicotinate dehydrogenase subunits (17), 2-methyleneglutarate mutase and methylitaconate isomerase (24).

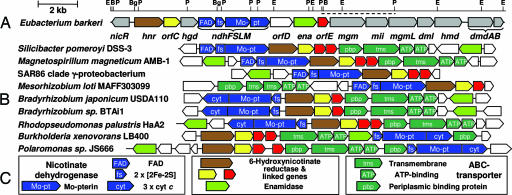

Fig. 2.

Nicotinate catabolism gene clusters. (A) The nicotinate fermentation gene cluster of E. barkeri with the PstI fragment (24), indicated by a dashed line and BamHI, BglII, EcoRI, and PstI restriction sites (B, Bg, E, and P), is shown. Genes associated with conversion of 2-formylglutarate to propionate and pyruvate are in gray. (B) Gene clusters associated with nicotinate catabolism via THON (descriptions and accession codes in Supporting Text). (C) Key: Genes with unclear association to nicotinate catabolism are colorless.

An overview of the E. barkeri nicotinate fermentation gene cluster is shown in Fig. 2A. The central region harbors 17 convergently transcribed genes (hnr to dmdB, nucleotides 3,069 to 21,980), which are overlapping or have short intergenic regions, typical for gene clusters associated with bacterial catabolic pathways. Ten genes encode seven structural enzymes of nicotinate fermentation. Three genes can be assigned to two structural enzymes based on amino acid sequence identity with enzyme classes of known function. One gene encodes a postulated 2-methyleneglutarate mutase repair enzyme (mgmL), and two genes are tightly linked to hnr genes in nicotinate gene clusters of Proteobacteria (orfC and orfE; see Fig. 2). The function of orfD, encoding a putative transmembrane protein, is unclear. Downstream of dmdB, two further genes (orfFG; data not shown) with an unknown relation to nicotinate fermentation are present. Upstream, the nicotinate catabolon is flanked by a divergently transcribed gene encoding a LysR-type regulator (designated as nicR) and two genes of unclear association (orfAB; data not shown). Such LysR-type regulators have been observed downstream of numerous gene clusters associated with degradation of aromatic compounds (33). The chemical inducer could be 6-hydroxynicotinate, which is known to accumulate early in the growth phase (3), similar to transcriptional activation by pathway intermediates in aromatic degradation.

Nicotinate Dehydrogenase.

For the first time to our knowledge, the complete primary sequence of a nicotinate dehydrogenase has been determined. The ndhF, ndhS, ndhL, and ndhM genes encode the 33-, 23-, 50-, and 37-kDa subunits of the E. barkeri nicotinate dehydrogenase based on the known N-terminal sequences (17). In agreement with the presence of FAD and two [2Fe-2S] clusters (16, 17), high sequence identities of NdhS and NdhF were found with the 2×[2Fe-2S]- and FAD-containing subunits/domains of xanthine dehydrogenases, respectively. NdhF lacks the insert with [4Fe-4S] cluster coordinating cysteines observed in 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA reductase (34). The 17-bp overlapping ndhL and ndhM genes formed two separate transcriptional units in different frames, with ndhM preceded by a Shine–Dalgarno sequence. NdhL is terminated by a TAA rather than a potentially selenocysteine-encoding TGA codon. These two subunits correspond to the two molybdopterin domains of the ≈85-kDa subunit of xanthine dehydrogenase-like enzymes (34, 35). Only three other two-subunit proteins of this type could be identified by literature and database searches with NdhLM: the (nonselenocysteine) selenium-containing purine dehydrogenase from C. purinolyticum (54 and 42 kDa) (19) and the xanthine dehydrogenase-like proteins both from Mesorhizobium loti (mlr1703/mlr1704) and encoded by an environmental sequence (AACY01708552). A two-subunit nature is not characteristic for this special class of enzymes because (nonselenocysteine) selenium-containing xanthine dehydrogenases from C. purinolyticum (19) and E. barkeri (21) both have an ≈85-kDa molybdopterin subunit.

The [Fe-S]-Flavoenzyme 6-Hydroxynicotinate Reductase.

Because activity was lost with a half-life of 90 min in air-saturated solutions, 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase was purified from nicotinate-grown E. barkeri cells under strictly anaerobic conditions. This observation accounts for the improved specific activity of 350 units/mg compared with the previously reported 24 units/mg for the aerobically purified enzyme (7). The 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase is a brown homotetrameric [Fe-S]-flavoprotein (4 × 53 kDa) with up to 9.3 Fe and 6–8 acid-labile sulfur atoms per subunit. UV-visible spectroscopy showed broad bands between 300–900 nm, which partially bleached on dithionite or THON reduction and disappeared upon acid denaturation of the [FeS] clusters (data not shown). After denaturation, visible absorbance bands at 360 and 450 nm, amounting to 0.8 flavin per subunit, were observed. The flavin is covalently bound because, upon SDS/PAGE electrophoresis, fluorescence comigrates with the denatured polypeptide (Fig. 3A); however, the site and type of covalent attachment has yet to be determined.

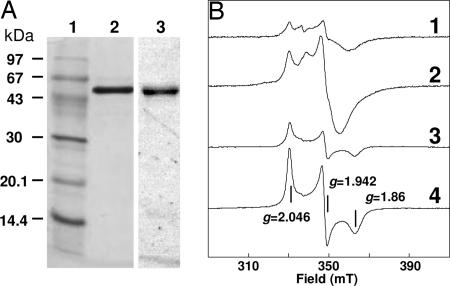

Fig. 3.

The enzyme 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase from E. barkeri. (A) SDS/PAGE. Lanes: 1, protein marker; 2 and 3, purified enzyme (2 μg) (1 and 2, Coomassie staining; 3, covalently bound flavin by UV-induced visible fluorescence). (B) EPR spectra of 36 μM purified enzyme in 20 mM KPi, pH 7.4. Spectra: 1, reduced with 10 mM THON, recorded at 10 K and 0.5 mW microwave power; 2, as 1, but reduced with 2 mM sodium dithionite; 3, as 1, but recorded at 40 K and 127 mW microwave power; 4, as 3, but reduced with 2 mM sodium dithionite. EPR conditions: modulation frequency, 100 kHz; microwave frequency, 9.460 GHz; modulation amplitude, 1.25 mT. Amplitudes of spectra 3 and 4 have been enlarged 4-fold.

The EPR spectrum of dithionite-reduced 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase exhibited a well resolved rhombic signal (g = 2.046, 1.942, and 1.86) between 20 and 60 K (Fig. 3B). Relaxational behavior and g values were typical for an all-cysteine coordinated [2Fe-2S]1+ cluster. Double integration of the signal at 40 K amounted to 0.49 spins per subunit. THON reduction (Em = −390 mV) only generated 0.19 spins per subunit of this signal. Upon lowering temperature, the [2Fe-2S]1+ signal gradually broadened and was superimposed by other signals at g = 1.99, 1.93, and 1.89. At elevated microwave power, broad wings typical for magnetically interacting [Fe-S] clusters became apparent. Double integration of the low temperature signals under nonsaturating conditions amounted to 1.1 spins per subunit (0.36 spins per subunit with THON reduction). The observed substoichiometry of EPR spin integration vs. Fe/S content probably results from the low redox potential of the clusters.

A 26 amino acid N-terminal sequence was determined by Edman degradation and identified the gene in the sequenced DNA (hnr; see Fig. 2A). Database searches recognized nine proteobacterial homologs (see Fig. 2B) with an overall amino acid sequence identity of 35–38% and revealed that the E. barkeri 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase is composed of four parts. It has an N-terminal extension (amino acids 1–53) with two CXXCXXCXXXC sequence motifs typical for ferredoxins binding two [4Fe-4S]2+/1+ clusters (absent in the homologs) and a CXXCPXXCX7GACXRY motif (amino acids 54–103) present in the N-terminal part of the homologs. These regions are linked by an unconserved section (amino acids 104–118) to a main domain (amino acids 119–499) exhibiting 41–45% sequence identity with the homologs. This modularity is reminiscent of hydrogenase in which an N-terminal ferredoxin-like domain functions as electron donor/acceptor, and a median cluster wires electrons to the active site at the heart of the protein. Based on EPR spectroscopic evidence for a [2Fe-2S] cluster magnetically coupled to another [Fe-S] cluster, we propose that the CXXCPXXCX7GACXRY motif forms the binding site for the [2Fe-2S] cluster, which is at a distance of <12 Å from two ferredoxin-like [4Fe-4S]2+/1+ clusters at the N-terminus. This arrangement would define an electron flow from the physiological electron donor ferredoxin, reduced by pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, to the N-terminal 2 × [4Fe-4S]2+/1+ clusters followed by single electron transfers via the median [2Fe-2S] cluster to the covalently bound flavin in the active site. Heterologous expression in Escherichia coli has not been successful and might require coexpression of orfC and/or orfE, which lie immediately downstream of the hnr homologous genes.

Enamidase, a Bifunctional Enzyme Belonging to the Amidohydrolase Family.

Previous studies indicated that nicotinate-grown E. barkeri extracts catalyzed the hydrolysis of THON to ammonia and a labile compound tentatively identified as 2-formylglutarate (29). This compound was transparent at the absorbance maximum of THON (ε273 nm = 11.2 mM−1cm−1) and yielded the 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone of glutaric semialdehyde, thought to result from decarboxylation. Based on these observations, we decided to isolate the hydrolytic enzyme that will be called enamidase. This name reflects the enamide moiety of THON subject to amidase action.

Instead of discontinuous assays using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, a continuous UV-spectrophotometric method was developed. Hydrolysis of THON was followed in cuvettes with a pathlength of 1–2 mm at 307 nm (ε = 1.1 mM−1cm−1). THON was obtained either by enzyme-catalyzed reduction of 6-hydroxynicotinate or chemical synthesis by means of a modified literature procedure (29). Both methods gave identical material as judged by activity measurement, UV-, 13C- and 1H-NMR spectroscopy (data not shown). A four-step purification of enamidase from cell extracts of E. barkeri grown on nicotinate gave homogeneous preparations exhibiting a single 40-kDa band on SDS/PAGE (Fig. 4A). Gel filtration showed that the protein is homotetrameric. Enamidase contains 1.0 Fe and ≈0.6 Zn per subunit and exhibits weak visible absorbance bands from ferric iron that bleach upon dithionite reduction and slightly increase upon ferricyanide oxidation. The latter treatments did not significantly change the kinetic parameters of enamidase (57 units/mg with a Km for THON of 5 mM). Purified N-terminally Streptagged enamidase had identical properties.

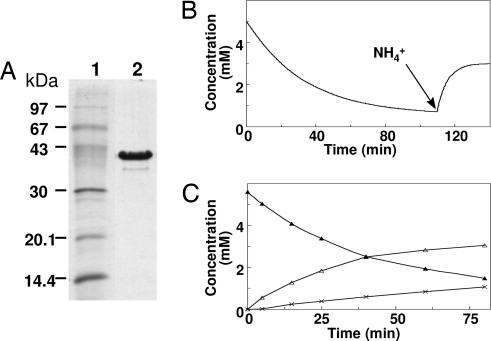

Fig. 4.

Enamidase from E. barkeri. (A) SDS/PAGE. Lanes: 1, protein marker; 2, 2 μg of purified enamidase. (B) Hydrolysis of 5 mM THON in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.4, at 23°C by 10 μg of enamidase and catalysis of the reverse reaction after addition of 200 mM (NH4)2SO4 (1-mm cuvette; THON concentration calculated with ε307 nm = 1.1 mM−1cm−1). (C) Hydrolysis of THON by enamidase and formation of (S)-2-formylglutarate. THON (1 ml, 5.6 mM) was incubated as in B, but with 5 μg of enzyme. Aliquots of 10 μl were diluted with 1 ml of 50 mM KPi, pH 7.4. THON (from a 272–nm absorbance; filled triangles) and (S)-2-formylglutarate concentrations (from NADH consumption 15 s after the addition of 10 units 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydrogenase; open triangles) were measured. The lowest trace shows the calculated difference between THON hydrolyzed and (S)-2-formylglutarate (crosses).

1H-NMR of crude reaction mixtures obtained upon incubation of THON with enamidase showed aldehyde peaks at 9.3 and 9.7 ppm. However, isolation and purification of 2-formylglutarate proved impossible because of decarboxylation. Enamidase not only catalyzed THON hydrolysis but also the reverse reaction after shifting the equilibrium by NH4+ addition (Fig. 4B). The UV-difference spectrum of the compound formed was identical to THON. This reverse reaction was not spontaneous, because no THON formation was detected in the absence of enamidase (data not shown).

The N-terminal sequence of the native enamidase and those of two internal tryptic peptides exactly matched residues 2–28, 45–68, and 271–290 of one of the gene products (designated as Ena). The calculated molecular mass minus the N-terminal methionine (39,793 Da) agreed with the mass determined by MALDI-TOF MS (39.75 ± 0.04 kDa). Enamidase shares 15–25% amino acid sequence identity with members of the α/β barrel amidohydrolase family and contains the typical metal-binding His-X-His pattern in the N-terminal part (36). Most enzymes of the family, typified by dihydroorotase, hydrolyze amide bonds, and contain binuclear metal centers bridged by a carboxylated lysine (see ref. 37 for a review). However, some members containing a mononuclear metal center (e.g., cytosine deaminase from Escherichia coli) do not hydrolyze amide bonds but eliminate ammonia via a carbinolamine intermediate (38). We therefore anticipate that the Fe/Zn binuclear metal center of enamidase catalyzes amide hydrolysis of THON, hydration, and ammonia elimination (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Proposed intermediates of the enamidase catalyzed THON hydrolysis.

2-(Hydroxymethyl)glutarate Dehydrogenase.

Cell-free extracts of nicotinate-grown E. barkeri cells exhibited a 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydrogenase (Hgd) activity of ≈0.3 units/mg. This activity was measured in the nonphysiological (reverse) direction by monitoring NADH formation with racemic 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate. Purification of the low abundance Hgd was problematic because of instability even under anaerobic conditions. Despite >95% activity loss, specific activities of up to 200 units/mg could be obtained. These preparations exhibited a major band with an apparent mass of ≈32 kDa on SDS/PAGE (data not shown). The Km for racemic 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate was 1.1 mM (at 5 mM NAD+) and that for NAD+ was 0.1 mM [at 10 mM racemic 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate]. Because no activity was observed with NADP+, it is unlikely that the NADPH produced by nicotinate dehydrogenase is the substrate for the Hgd-catalyzed reduction of 2-formylglutarate. An NADPH:NAD+ transhydrogenase could supply an additional source of energy via the difference in electrochemical potentials of nicotinate/6-hydroxynicotinate [<−380 mV (12)] vs. 2-(hydroxymethyl)-/2-formyl-glutarate couples (estimated to be −200 mV).

Upstream of ndhFSLM, a gene was identified which encoded a protein (30,874 Da) with 37% and 38% amino acid sequence identity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase and Escherichia coli tartronate reductase, respectively. Comparison of 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate with substrates of these and other enzymes of the 3-hydroxyisobutyrate/phosphogluconate dehydrogenase family (39) revealed a common substituted 3-hydroxypropionate moiety. With the anticipation that Hgd was encoded by this gene, we purified the corresponding N-terminally Streptagged protein after heterologous expression in Escherichia coli. The tetrameric protein (4 × 32.5 kDa, including tag) had a specific activity and Km values similar to those of partially purified wild-type enzyme.

Conversion of 2-(Hydroxymethyl)glutarate to 2-Methyleneglutarate.

Because the substrates for Hgd and 2-methyleneglutarate mutase are free carboxylates, either transient formation of CoA-esters would have to occur or a [4Fe-4S]-cluster containing dehydratase could be involved. A gene in the 23.2-kb DNA fragment encodes a protein of 471 amino acids with similarity to both α- and β-subunits of labile [4Fe-4S]-containing bacterial serine dehydratases (40). The N-terminal amino acid sequence showed 31% identity with the Lactobacillus johnsonii serine dehydratase α-subunit (LJ1328) and the C-terminal part had 28% identity with the corresponding β-subunit (LJ1329). Three conserved cysteines (171, 214, and 224) match those proposed to coordinate the [4Fe-4S] cluster in the serine dehydratase α-subunit (40). The presence of HOCH2-CH-CO2− substructures both in 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate and l-serine lends support to the argument that this gene (hmd; Fig. 2A) encodes 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydratase. Purification of N-terminally Streptagged Hmd in an active form has not thus far been successful, presumably because of the same [4Fe-4S] cluster lability known for l-serine dehydratase (40).

Chirality of 2-Formylglutarate and 2-(Hydroxymethyl)glutarate.

Previous studies on E. barkeri nicotinate fermentation identified (R)-3-methylitaconate (23) and (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate (26) as chiral intermediates, but chirality of 2-formyl- or 2-(hydroxymethyl)-glutarate has not been considered. Because an enantioselective synthesis of the latter substrate has not yet been accomplished, serine and 3-hydroxyisobutyrate enantiomers were used to determine the stereoselectivity of Hgd. The dehydrogenase catalyzed oxidation of (S)-serine (0.3 units/mg) and (S)-3-hydroxyisobutyrate (0.1 units/mg) but not the corresponding (R)-enantiomers (<0.005 units/mg). With the assumption that the HOCH2-CH-CO2− moieties of the probes and 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate are bound in the active site in a comparable manner, it reasonable to conclude that (S)-2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate and thus (S)-2-formylglutarate are the physiological intermediates.

The stereospecificity of Hgd was used to determine the chirality of the 2-formylglutarate formed by enamidase action. Spontaneous hydrolysis of 2-(enamine)glutarate would lead to racemization. If, however, 2-(enamine)glutarate would not be released from the binuclear center of enamidase, a proton could stereospecifically be added to C-2, forming a chiral iminium intermediate (Fig. 5). After hydration to 2-(carbinolamine)glutarate, loss of ammonia would yield (S)-2-formylglutarate, the substrate for Hgd. When THON was incubated with enamidase initially 0.98 equivalents of (S)-2-formylglutarate were recovered per mole of THON hydrolyzed, which progressively decreased to 0.74 over 80 min (Fig. 4C). This loss probably results from decarboxylation of (S)-2-formylglutarate and racemization. We note that the (S)-2-formylglutarate determination was carried out quickly (20 s) to avoid overestimation of (S)-2-formylglutarate by racemization during the Hgd assay. After removal of enamidase by membrane filtration, (S)-2-formylglutarate solutions could be used to determine a Km of 0.061 mM (at 0.25 mM NADH) and 0.016 mM for NADH [at 1.2 mM (S)-2-formylglutarate].

(2R,3S)-Dimethylmalate Dehydratase and Lyase.

Partial enrichment of the Fe2+-dependent and oxygen-sensitive (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate dehydratase from E. barkeri has been reported (28). Analysis of the cloned E. barkeri sequence identified two genes (dmdAB) encoding proteins with amino acid sequence identities of 70% to archaeal proteins of the aconitase family (41) and 30% with biochemically characterized eubacterial isopropylmalate isomerase subunits. Inclusion of (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate dehydratase in the aconitase family is further supported by the presence of conserved cysteine residues at position 301, 361, and 364 in DmdA, typical for [4Fe-4S] cluster coordination in other members.

(2R,3S)-Dimethylmalate lyase is encoded by the dml gene that has been expressed in Escherichia coli. The purified enzyme is a homotetramer (4 × 31.4 kDa) and has the same Mg2+ dependence and catalytic properties as from wild type (25). A primary sequence identity of 36% with Escherichia coli 2-methylisocitrate lyase and the conserved KKCGH active site motif (42) defined Dml as a member of the isocitrate lyase family.

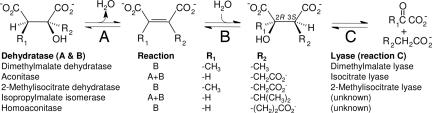

Dehydratases and lyases acting on (2R,3S) 3-substituted malate substrates (Fig. 6) can be found in many pathways: (methyl)citrate and glyoxalate cycle, lysine biosynthesis via homoaconitate, coenzyme B biosynthesis, and, as shown here, in nicotinate fermentation. Primary sequence and structural conservation in the aconitase and isocitrate lyase families seem to be inherently linked to stereoselectivity.

Fig. 6.

Dehydratase and lyase pairs acting on the (2R,3S)-3-substituted malate moiety.

Nicotinate Catabolism in Other Organisms.

Database searches identified nine Proteobacteria with gene clusters encoding proteins with amino acid sequence identities of 40–46, 17–38, 40–43, and 42–47% to E. barkeri, NdhS, NdhLM, Hnr, and Ena, respectively (see Fig. 2B). These observations led us to postulate that these organisms are nicotinate-catabolizing Proteobacteria (NCP), which have the first three enzymes in common with E. barkeri. This assumption is supported by preliminary data, which show that the heterologously expressed Bradyrhizobium japonicum ena homolog has kinetic parameters similar to that of E. barkeri enamidase. The α-Proteobacterium Azorhizobium caulinodans is known to catabolize nicotinate via THON (6, 43) and can therefore be expected to harbor genes similar to those of the nine NCPs. In M. loti, THON hydrolysis might be carried out by an evolutionary divergent type of enamidase, because no Ena homolog is encoded on the genome. Further catabolism of 2-formylglutarate in the nine NCPs probably proceeds via the glutarate/glutaryl-CoA pathway identified in A. caulinodans (43) and thus explains the absence of hgd, hmd, mgm, mii, dmdAB, and dml homologs.

The gene clusters of eight NCPs contained ABC-transporter encoding genes (Fig. 2B). These genes are presumably involved in nicotinate transport as the B. japonicum periplasmic binding protein has submicromolar affinity for nicotinate (data not shown). Five NCPs lacked flavin-binding NdhF homologs but had C-terminal extensions to the NdhLM homologs with CXXCH cytochrome c binding motifs (three each). Instead of NAD(P)+, these nicotinate dehydrogenases might link to the respiratory chain, as in A. caulinodans (43). Gene clusters containing nicotinate dehydrogenases with C-terminal tricytochrome c extensions but without hnr and ena were found in Pseudomonads (data not shown). This finding unravels gene clusters associated with nicotinate catabolism via 2,5-dihydroxypyridine, because 6-hydroxynicotinate monoxygenase (4) and maleate cis-trans-isomerase homologous genes were found adjacent.

Concluding Remarks.

Fifty years after the discovery of a soil bacterium fermenting nicotinate (8), the plethora of enzymes and cofactors involved in the pathway can now be understood at a molecular level. Two nonmetalloenzymes and seven metalloenzymes containing molybdopterin, selenium, FAD, [2Fe-2S], covalently bound flavin, [4Fe-4S], binuclear Fe-Zn, adenosylcobalamin, and Mg2+ catalyze nine highly unique reactions. Structural characterization is in progress and will extend our knowledge on the enzymes at the atomic level.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Cell Growth.

E. barkeri (DSMZ 1223) was grown under anaerobic conditions at 32°C with nicotinate medium in a 100-l fermentor (24).

Molecular Biology.

λ-ZAP-Express phage libraries (30) were prepared by ligation of EcoRI or BamHI/BglII-digested E. barkeri DNA into EcoRI or BamHI cut λ-DNA according to manufacturer’s protocol (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Phage plaques were screened with Southern blot hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes based on the known PstI fragment (24), already cloned DNA fragments, or PCR fragments obtained with primers derived from ≈400 bp reads of direct genomic sequencing at GATC (31). pBK-CMV plasmids were generated by in vivo excision and circularization of λ-phage DNA of positive plaques (30). Thus, two EcoRI (1.5 and 4.9 kbp), a 5.4-kbp BglII/BamHI fragment, a 4.2-kbp BglII fragment, and a 2.3-kbp EcoRI fragment were cloned. The extreme 5′ and 3′ ends of the contig were obtained by TOPO TA-cloning (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) of PCR fragments. Primers for PfuHotstart amplification were derived from direct genomic sequencing data and nested PCR by using SeeGene DNA walking with gene specific and annealing control primers (32). Details on cloning and sequencing can be found in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Substrates.

THON was synthesized from coumalic acid (29) omitting UV-induced (E/Z) isomerization of dimethyl-2-aminomethyleneglutarate. Synthesis of 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate was by saponification (0.1 M NaOH in ethanol for 10 h at room temperature) of NaBH4-reduced dimethyl 2-formylglutarate obtained by condensation of ethylformate and NaH-treated dimethylglutarate in ether (0°C for 4 h, then room temperature for 10 h). Preparation of 2-formylglutarate was by incubation of 10 mM THON in 20 mM KPi at pH 7.4 with 40 units enamidase at 23°C for 20 min. After Centricon (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany) YM10 membrane filtration, such preparations contained ≈70 mol % enzymatically active 2-formylglutarate (i.e., NADH consumption in 20 s with 1 unit 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydrogenase in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.4) and a residual 20 mol % THON as judged by UV spectroscopy. The (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate was prepared according to ref. 26.

Activity Measurements.

The 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase was assayed according to ref. 7. Enamidase activity was measured by the decrease of THON absorbance in 50 mM CHES/NaOH, pH 9.5 (Δε307 nm = −1.1 mM−1cm−1). NADH production at 340 nm determined 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate dehydrogenase activity by using racemic 2-(hydroxymethyl)glutarate in 100 mM glycine/NaOH at pH 9.2. The (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate lyase activity was measured as in ref. 25.

Purification of Enzymes.

The 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase was isolated from soluble protein extracts of nicotinate-grown E. barkeri cells by FPLC purification by using Source 15Q, ceramic hydroxyapatite, and MonoQ columns in an anaerobic glovebox. Enamidase was purified aerobically with Source Phe substituting the second column and an additional MonoQ step. The (2R,3S)-dimethylmalate lyase was isolated from Escherichia coli BL21 transformed with pBluescript SK+ containing a KpnI-EcoRI fragment with E. barkeri dml. After heat-treatment of soluble protein, purification was effected by fractionated (NH4)2SO4 precipitation, Source Phe, and Source 15Q FPLC purification. Detailed purification protocols can be found in Supporting Text.

Expression and Purification of N-Terminally Streptagged Proteins.

Hnr, hmd and hgd genes were PCR amplified with PfuUltra (Stratagene) by using primers for BsaI ligation into pPR-IBA2 as suggested by Primer D’signer (IBA GmbH; Göttingen, Germany). For ena, Cfr42I and BamHI restriction sites were used. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) expression at 30°C and Streptactin II affinity chromatography was according to IBA specifications.

Other Biochemical Techniques.

Protein, Fe, S2− and flavin determination, gel-filtration, SDS/PAGE, MALDI-TOF MS, UV-visible, and EPR spectroscopy were performed as in ref. 44. Zinc was determined as in ref. 45. D. Linder (Giessen, Germany) N-terminally sequenced 6-hydroxynicotinate reductase blotted on PVDF. Purified enamidase was carboxymethylated and subjected to C4-RP HPLC and N-terminally sequenced (G. Mersmann; Münster, Germany), as well as two tryptic peptides (C18-RP HPLC, 0.1% TFA in water, 0–100% acetonitrile gradient).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Selmer for peptide analysis; Prof. R. K. Thauer for access to MALDI-TOF mass and EPR spectrometers; Profs. W. Buckel and B. T. Golding for discussion and support; and Drs. A. Fackelmayer (Genomic Analysis and Technology Core, Konstanz, Germany), O. Knobloch (Seqlab, Göttingen, Germany), and S. Zauner for help with sequencing. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft via the Graduiertenkolleg “Protein Function at the Atomic Level” (to A.A.).

Abbreviations

- NCP

nicotinate-catabolizing Proteobacteria

- THON

1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-6-oxonicotinate.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. DQ310789).

References

- 1.London J., Knight M. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1966;44:241–254. doi: 10.1099/00221287-44-2-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser J.-P., Feng Y., Bollag J.-M. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;60:483–498. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.483-498.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreesen J. R., Fetzner S. Met. Ions Biol. Syst. 2002;39:405–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakano H., Wieser M., Hurh B., Kawai T., Yoshida T., Yamane T., Nagasawa T. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;260:120–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagel M., Andreesen J. R. Arch. Microbiol. 1990;154:605–613. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitts C. L., Schaechter L. E., Rabin R. S., Ludwig R. A. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:3406–3411. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3406-3411.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holcenberg J. S., Tsai L. J. Biol. Chem. 1969;244:1204–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harary I. Nature. 1956;177:328–329. doi: 10.1038/177328a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stadtman E. R., Stadtman T. C., Pastan I., Smith L. D. J. Bacteriol. 1972;110:758–760. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.2.758-760.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastan I., Tsai L., Stadtman E. R. J. Biol. Chem. 1964;239:902–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai L., Pastan I., Stadtman E. R. J. Biol. Chem. 1966;241:1807–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holcenberg J. S., Stadtman E. R. J. Biol. Chem. 1969;244:1194–1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kung H. F., Cederbaum S., Tsai L., Stadtman T. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1970;65:978–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.65.4.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kung H. F., Stadtman T. C. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:3378–3388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gladyshev V. N., Khangulov S. V., Stadtman T. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:232–236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gladyshev V. N., Lecchi P. Biofactors. 1996;5:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gladyshev V. N., Khangulov S. V., Stadtman T. C. Biochemistry. 1996;35:212–223. doi: 10.1021/bi951793i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dilworth G. L. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1982;219:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Self W. T., Stadtman T. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7208–7213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner R., Cammack R., Andreesen J. R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;791:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schräder T., Rienhöfer A., Andreesen J. R. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;264:862–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber R., Hof P., Duarte R. O., Moura J. J. G., Moura I., Liu M.-Y., LeGall J., Hille R., Archer M., Romão M. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8846–8851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartrampf G., Buckel W. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986;156:301–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beatrix B., Zelder O., Linder D., Buckel W. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;221:101–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirzer P., Lill U., Eggerer H. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem. 1979;360:1693–1702. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1979.360.2.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lill U., Pirzer P., Kukla D., Huber R., Eggerer H. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem. 1980;361:875–884. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1980.361.1.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Löhlein G., Eggerer H. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem. 1982;363:1103–1109. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1982.363.2.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kollmann-Koch A., Eggerer H. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem. 1984;365:847–857. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1984.365.2.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai L., Stadtman E. R. Methods Enzymol. 1971;18B:233–249. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Short J. M., Fernandez J. M., Sorge J. A., Huse W. D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7583–7600. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heiner C. R., Hunkapiller K. L., Chen S. M., Glass J. I., Chen E. Y. Genome Res. 1998;8:557–561. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.5.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang I. T., Kim Y. J., Kim S. H., Kwak C. I., Gu Y. Y., Chun J. Y. BioTechniques. 2003;35:1180–1184. doi: 10.2144/03356st03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tropel D., van der Meer J. R. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:474–500. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.474-500.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unciuleac M., Warkentin E., Page C. C., Boll M., Ermler U. Structure (London) 2004;12:2249–2256. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonin I., Martins B. M., Purvanov V., Fetzner S., Huber R., Dobbek H. Structure (London) 2004;12:1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holm L., Sander C. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 1997;28:72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seibert C. M., Raushel F. M. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6383–6391. doi: 10.1021/bi047326v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ireton G. C., McDermott G., Black M. E., Stoddard B. L. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;315:687–697. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawes J. W., Harper E. T., Crabb D. W., Harris R. A. FEBS Lett. 1996;389:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmeister A. E. M., Textor S., Buckel W. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:4937–4941. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4937-4941.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irvin S. D., Bhattacharjee J. K. J. Mol. Evol. 1998;46:401–408. doi: 10.1007/pl00006319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimm C., Evers A., Brock M., Maerker C., Klebe G., Buckel W., Reuter K. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:609–621. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitts C. L., Lapointe J. P., Lam V. T., Ludwig R. A. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:7791–7797. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7791-7797.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dickert S., Pierik A. J., Buckel W. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:49–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunt J. B., Neece S. H., Schachman H. K., Ginsburg A. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:14793–14803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.