Abstract

Amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange rates have been determined for two mutants of α-spectrin Src homology 3 domain (WT), containing an elongated stable (SHH) and unstable (SHA) distal loop. SHA, similarly to WT, follows a two-state transition, whereas SHH apparently folds via a three-state mechanism. Native-state amide hydrogen exchange is effective in ascribing energetic readjustments observed in kinetic experiments to species stabilized within the denatured base and distinguishing those from high-energy barrier crossings. Comparison of ΔGex and mex parameters for amide protons of these mutants demonstrates the existence of an intermediate and allows the identification of protons protected in this state. The consolidation of a form containing a prefolded long β-hairpin induces the switch to a three-state mechanism in an otherwise two-state folder. It can be inferred that the unbalanced high stability of individual elements of secondary structure in a polypeptide could ultimately complicate its folding mechanism.

Keywords: kinetics‖β-hairpin

The Src homology 3 (SH3) domain from α-spectrin is a well-characterized model system for protein folding and stability (1). It was shown early that this domain folds by a two-state transition (2) and that its isolated secondary structure elements are quite unstructured (3). We have investigated (4) the consequences of fusing the SH3 domain with a short sequence KITVNGKTYE (BHH) that tends to fold as a stable β-hairpin (5). In the SHH-Bergerac mutant (SHH for short) the two-residue distal β-turn (N47-D48) of α-spectrin SH3 has been substituted by BHH. SHH is more stable and folds significantly faster than the short WT α-spectrin SH3 at moderate urea concentrations, but unlike WT, its folding rate levels off under strong folding conditions (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org), thus deviating from the simplest two-state folding mechanism. Mutation of two residues in the inserted BHH region of SHH (Ile-2′ and Val-4′ to Ala, SHA-Bergerac) destabilizes the protein and switches it back to a two-state folding process (Fig. 6). When fused to WT, the inserted BHH and BHH_I2′A_V4′A sequences adopt a fully folded β-hairpin structure protruding from the protein (4), but the corresponding isolated peptides are, respectively, ≈30% folded (BHH) and fully unfolded (BHH_I2′A_V4′A).

Understanding the reasons behind rate constant deviations could be important in improving the methods available for in vitro protein stabilization, as well as in revealing limiting steps related to switches from two to higher order folding mechanisms. Deviations in chevron plots do not have an unequivocal interpretation. Rate constants reflect free energy differences from reactants to the highest energy level in the reaction coordinate or transition state (‡). The deviations often occurring at lower denaturant concentrations in refolding experiments are usually assigned to changes within the denatured ensemble, i.e., a new energy level or intermediate state (I) is stabilized (Fig. 1, plots I and III). Curved chevron plots also have, although less frequently, been associated to movements of a single ‡ ensemble (6) or to multiple sequential barriers (ref. 7; Fig. 1, plots II and IV). Unambiguous proof of whether barrier crossings are occurring in the ground, denatured, or the highest, ‡, energy levels could be provided by any experiment that allows the direct measurement under native conditions of k‡-F or ΔGF-U, where F is the native state and U is the fully unfolded state. Under these conditions, F is overwhelmingly populated, and most spectroscopic methods allow a direct measure of k‡-U but provide only estimates of k‡-F or ΔGF-U obtained by extrapolation from values measured under denaturing conditions. Hydrogen exchange (HX) analysis results are extremely valuable in this sense because this technique is blind for F. Depending on the condition used, EX1 or EX2, one can have a measure of k‡-F (8–10) or ΔGU-F (11–14), respectively.

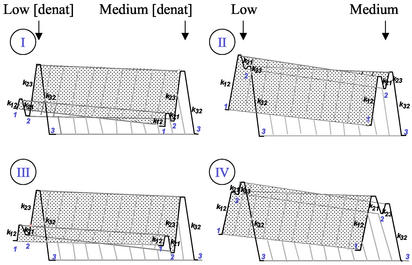

Figure 1.

Four schematic plots of the total free energy versus denaturant concentration of kinetically relevant states (N, U, I, and ‡). All schemes are equally compatible with a curved kinetic chevron plot for protein folding. (Left) On-pathway (I) and off-pathway (III) stable folding intermediate. (Right) The arising of earlier (II) or later (IV) barriers within the ‡ ensemble. In II and IV, deviations in lnk‡-U would be accompanied by a curvature in the unfolding limb, lnk‡-F, at low denaturant concentration, parallel to the one found in refolding, which would produce a linear dependence of the total free energy versus denaturant concentration. The difference between diagrams on the right and on the left is not the existence of folding intermediates, but their stability. ΔGex is unaffected by high energy intermediates.

HX is used here as one of the few tools that could help identify the events responsible for the observed curvature in the SHH chevron plot. If a new state, I, more stable than U is emerging in the SHH landscape, under moderately native conditions, protein molecules should populate each ensemble or state (F, U, or I) according to the free energies extracted from folding kinetics. Additionally, analysis of the HX data collected for the subset of protected amides in SHH and SHA mutants should provide data to distinguish protons submitted to partial openings, to semifolded forms within the folded ensemble, from those unprotected in I. The low-resolution structure of I at the level of preserved hydrogen bonds should shed light on rate-limiting steps in SHH folding.

Materials and Methods

1H-NMR Spectroscopy.

Amide exchange was initiated by suspending the lyophilized protein sample in 600 ml of 0–3 M urea (ultrapure, Roche Molecular Biochemicals), pD 3.0 dissolved in 100% 2H2O (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Cambridge, MA). As exchange occurs in D2O, 0.4 is added to the pH meter reading to correct for the glass electrode solvent isotope artifact, pD = pH (read) + 0.4. Protein concentration ranged from 1 to 2 mM. Sodium 3-trimethylsilyl (2,2,3,3-2H4) propionate was used as an internal reference at 0.00 ppm. The sample was equilibrated at 298 K for 5 min in a Bruker DRX-500 pulse spectrometer, and 1H total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) spectra were acquired by applying the standard MLEV17 spinlock sequence with 80-ms mixing time, using the time proportional phase incrementation technique. Each 1H TOCSY spectrum took 1 h and 38 min. Slowly exchanging amide protons were identified by means of cross-peaks in the fingerprint region in 1H TOCSY spectra that were integrated by means of brucker software. Volume integrals were normalized to the peak corresponding to nonexchangeable Hd-He protons of Tyr-15.

Data Analysis.

Amide HX rate constants (kex) were obtained by fitting the time course of cross-peak volume decrease to a first-order exponential by using kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA):

|

where I is the peak intensity, I0 is the peak intensity at time 0, and b is the baseline correction term. Random coil HX rate constants, kint, can be obtained with the sphere program provided by the Roder laboratory at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia (www.fccc.edu/research/labs/roder/). The average value of kint at pH 3.0 is 0.0025 s−1, yet the F fluorescence signal is gained with an effective rate constant ranging from 34 to 4 s−1 in all conditions used. Hence, we can be confident that, in our experimental conditions, the closing rate associated with hydrogen bond formation during folding (>4 s−1) is comfortably larger than the intrinsic exchange rate. EX2 exchange (which is a necessary condition for determining ΔGex) was also assured by demonstration of ideal pH dependence (EX1 exchange is pH independent) and by the coincidence of ΔGex and ΔGU-F for slowly exchanging protons. Free energy of HX, ΔGex = −RT ln(K ) = −RT ln(kex/kint), where K

) = −RT ln(kex/kint), where K is the apparent equilibrium constant calculated from HX experiments, can be plotted as a function of denaturant for each probe and fitted to the equation ΔGex = ΔGex(0 M) + mex [urea].

is the apparent equilibrium constant calculated from HX experiments, can be plotted as a function of denaturant for each probe and fitted to the equation ΔGex = ΔGex(0 M) + mex [urea].

Ensemble Calculations.

The linear unfolded structure of the SHH was submitted to a distance geometry and combined simulated-annealing/maximum-likelihood model refinement protocol by means of the Crystallography and NMR System (15). Distance restraints were imposed among residues connected by hydrogen bonds. Several rounds were run after sequentially eliminating from the restraints list each of the four groups of hydrogen bonds, according to ΔGex of the corresponding amide hydrogen (NH).

Results

Fig. 6 shows the chevron plots (lnk vs. [urea]) for SHH and SHA, as well as estimates for lnk‡-F, lnk‡-U, and ΔGF-U/RT for SHH extracted from these kinetic data. The kinetic parameters obtained at 298 K, pH 3.0 in 50 mM sodium citrate are as follows for SHH and SHA, respectively: k‡-F = 0.15 ± 0.02 and 0.29 ± 0.01 s−1; k‡-U = 249 ± 18 and 31 ± 0.6 s−1; ΔGF-U = −4.4 ± 0.1 and −2.8 ± 0.3 kcal⋅mol−1; KI-U = 5.7 ± 0.5 and negligible; and mI-U = 0.77 ± 0.2 kcal⋅mol−1⋅M−1 and unknown. According to the more conventional interpretation, the refolding of SHH occurs via the formation of a transient I, which under native conditions at pH 3.0 is ≈6-fold more populated than U and ≈300-fold less populated than F. The free energy of I decreases linearly versus [urea] with respect to U: at 0 M urea I is 1 kcal⋅mol−1 more stable than U for SHH; at 1.3 M urea both states have the same free energy and should be equally populated; and, at higher urea concentrations, U is more stable.

SHH Exchange Rates Under Native Conditions.

Most of the NH-CαH cross-peaks of SHH residues appear well resolved in the fingerprint region of the two-dimensional 1H-NMR experiment registered at pD 3.0 and 298 K (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). A total of 61 cross-peaks were present in the first spectra recorded 22 min after the initiation of exchange. The individual H/D exchange rates, kex (Fig. 8 and Tables 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and ΔGex of 51 of these NHs were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

NHs highly protected from exchange in F, under EX2 conditions, could be protected or exposed to direct exchange with solvent in any populated stable I. Those NHs not protected in I would exchange much more rapidly, with ΔGex = ΔGI-F. In other words, for these NHs, I behaves as U, K = ([U] + [I])/[F]. On the other hand, those NHs protected in I, as much as in F, would show a ΔGex = ΔGU-F, [K

= ([U] + [I])/[F]. On the other hand, those NHs protected in I, as much as in F, would show a ΔGex = ΔGU-F, [K = ([U]/[F] + [I]) ≈ [U]/[F]]. Conversely, if ln k‡-U deviations are caused by a switch between different rate-determining steps, no consequences are expected in the observed exchange rates, as very high energy states are faintly populated and do not affect stability. High-energy intermediates in the later case would remain undetected in the equilibrium HX experiment.

= ([U]/[F] + [I]) ≈ [U]/[F]]. Conversely, if ln k‡-U deviations are caused by a switch between different rate-determining steps, no consequences are expected in the observed exchange rates, as very high energy states are faintly populated and do not affect stability. High-energy intermediates in the later case would remain undetected in the equilibrium HX experiment.

Results of the HX analysis on SHH are summarized in Fig. 4 as the distribution of ΔGex throughout the sequence and by a color code at the level of secondary and global structure in Fig. 2. As expected, isotope exchange rates for SHH NHs depend primarily on the amide's intramolecular hydrogen bonding and access to the solvent (17). In general, the most stable regions of SHH, those showing slowly exchanging amide protons, coincide with the secondary structure elements. Hydrogens located at buried peptide amide linkages show slow exchange, whereas NHs located in loops and flexible regions on the protein surface are usually hydrogen-bonded only to water and have good access to solvent, therefore exchanging rapidly.

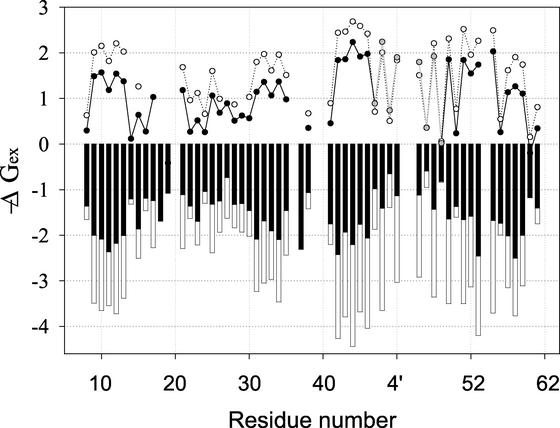

Figure 4.

Superimposition of ΔGex at pD 3.0 obtained for SHA (filled bars) and SHH (empty bars) in the absence of denaturant. Filled circles (gray in the BHH inserted sequence) represent the subtraction of these two values for each proton. Open circles represent ΔΔGex of SHH at 0 M relative to 3 M urea.

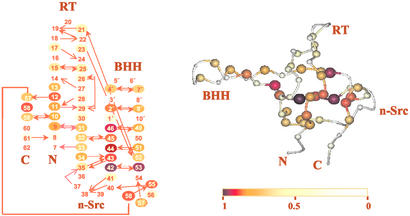

Figure 2.

Distribution of unfolding HX free energies (ΔGex) of SHH in native conditions pD 3.0, at 298 K. (Left) Hydrogen bond diagram of the of SHH model. Filled arrows indicate backbone–backbone, donor to acceptor. Empty arrows are used when the acceptor is a side chain group. (Right) Ribbon representation of the modeled structure of the SHH. Each sphere represents a backbone amide site colored according to the ratio ΔGex/ΔGF-U; the sphere radius is also inversely proportional to this ratio. The figure was prepared with the program molmol (16).

We find few amide protons (W42, V44, and V53) at pH 3.0 and 298 K with exchange rates dictated by global unfolding of the protein, ΔGex ≈ ΔGU-F = 4.4 ± 0.4 kcal⋅mol−1. These residues are involved in the hydrogen bonding network within the distal hairpin (third and fourth β-strands), now fused to BHH. W42 and V53 are doubly hydrogen-bonded to each other, whereas V44 and V46 pair with G51 and K49, respectively, which are protected to a lesser extent. In the fused BHH sequence, steadily decreasing ΔGex values are obtained from the N and C termini to the β-turn. The saw shape of ΔGex distribution within this region (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) displays the hydrogen bond pattern expected for a 2:2 antiparallel β-hairpin (18).

NHs located in the N- and C-terminal strands of the protein and the 310 helix (residues 54–58) also exhibit high protection. It should be noted that these regions are important determinants of protein topology. Residues in the outside strands of both β-sheets have, overall, lower protection than the central strands.

On the other hand, hydrogen bonds defining the RT loop (residues 14–26) are more labile in general. This loop is anchored to the distal hairpin, partially wrapping the domain core, with only one couple of hydrogen bonds from V23 and F52 amide protons to F52 and R21 carbonyls, respectively. The adjacent second strand (residues 30–35) serves as an edge for both β-sheets and is slightly less protected than the first and third central strands with ΔGex ≈3 kcal⋅mol−1. Residues 36–40 are configuring the β-turn and β-bulge within the n-Src loop, with no main-chain hydrogen bond and, as expected, interchange rather fast with solvent.

In principle, there is no reason to think that there should be any correlation of the equilibrium exchange rates and the role that some side-chain groups have in folding kinetics. φ‡-U Values report on the latter and are assumed to be correlated to the structure of the ‡ ensemble (19). This state is, by definition, very high in energy and should not affect any measurement under equilibrium conditions (apart from its effect in exchange mechanism). In fact, we do not find any correlation between the protection factors and the φ‡-U values, as shown more dramatically in the case of the first β-strand that has φ‡-U values close to zero and large protection factors.

SHH Exchange Rates Versus Denaturant.

Increasing concentrations of denaturant stabilize unfolded and semifolded conformations of proteins according to the hydrophobic surface they expose. The HX method benefits from this fact to selectively alter the distribution of conformations in equilibrium. The mex value, measured as the slope of ΔGex versus [denaturant], indicates the magnitude of the opening motion responsible for the exchange of a given hydrogen. This parameter thus distinguishes between denaturant-dependent unfolding events and denaturant-independent local fluctuations.

SHH was titrated with increasing concentrations of urea at pD 3.0 and kex was determined for observable amide protons. At 3 M urea KI-U = 0.115 (I is 8.7 times less populated than the U), KF-U = 26.4, ΔGF-U = −1.94 kcal⋅mol−1.

The amide protons of residues 42, 44, and 53 show the maximal protection in the whole range of urea ΔGex ≈ ΔGU-F and mex ≈ mU-F. Residue 58 is incorporated in this group at 1.5 M urea. Other residues within the long β-hairpin (residues 46 and 2′) have very similar mex values but at a 0.2 kcal⋅mol−1 lower level. A second group of amide protons fuse in an isotherm somewhat lower. This group is composed mainly of residues located in the first, second, and third β-strands: V9 L10, A11, L12, L31, L34, K43, and Y57. V9 could serve as a marker for the global unfolding isotherm of this group of protons.

Another fraction of residues shows ΔGex values >0.8 kcal⋅mol−1 lower than the main unfolding isotherm. For many of them, the ΔGex values obtained are more independent of urea concentration, showing that these NHs exchange through small molecular fluctuations that have very small mex values (these openings give rise to the exposure of small hydrophobic surfaces). The global unfolding of this group of protons indicated by those with close to linear urea dependence (E45, Q51, and A55) have a mex value similar to the most protected group of protons. Other residues in this group are Y15, V23, T32, V4′, K7′, Y9′ R49, F52, and K59.

Most of the NHs showing very low ΔGex values belong to the RT loop or C terminus (E22, M25, G28, N35, and L61). M25 and N35 could be taken as representatives of this group, with a linear ΔGex dependence in the range from 1 to 3 M urea. The linear extrapolation of ΔGex renders a value of 2.8 kcal⋅mol−1 at 0 M urea and a mex value of −0.69 kcal⋅mol−1⋅M−1.

Conformational Ensembles.

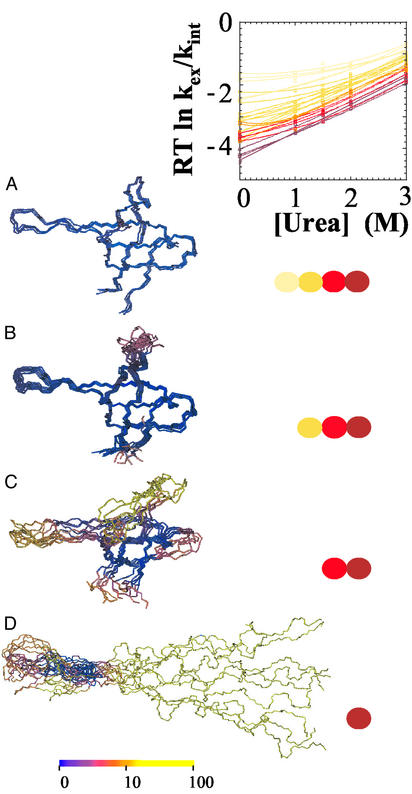

In principle, the HX method provides a means of exploring the excited-state manifold between the native and unfolded protein. In an attempt to exemplify the results obtained by this method on SHH on the basis of coexisting conformational ensembles, we have calculated the group of structures resulting after the partial unfolding of different regions. Hydrogen bonds involving protons with ΔGex 4.4 kcal⋅mol−1 remain disrupted in a fraction of time of 1 per 1,680, whereas those with ΔGex 2.8 kcal⋅mol−1 are broken in a proportion of 1 per 113. It could be easy to find the SHH protein in a conformation in which the latter are broken and the former remain intact. There is no evidence that protons with similar ΔGex values are unbonded simultaneously, nor that the ΔGex pattern reflects a staircase that the proteins follows in unfolding (20). The depiction we use here tries to illustrate a possible scenario, compatible with the HX data, of coexisting conformational ensembles in equilibrium. Hydrogen bonds are categorized as a function of the ΔGex values of the donor NHs into four groups: (i) 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 33, 37, 35, 40, 41, and 61; (ii) 15, 23, 32, 45, 4′, 7′, 9′, 49, 51, 52, 55, and 59; (iii) 9, 10, 11, 12, 31, 34, 43, 57, 58, and 2′; and (iv) 42, 44, 46, and 53. Clustering is made attending mainly to ΔGex at 0 M urea, where I is more populated, but also considering the urea dependence; e.g., Val-46 is added to the group of most protected protons, because it exhibits a constant mex, indicating that the slight difference of its ΔGex is most probably caused by its higher accessibility to solvent in F and not by an opening to a partially unfolded form.

The linear polypeptide with the SHH sequence was submitted to a simulated annealing protocol, complying with the constraints provided by the defined hydrogen bonds in the model structure of SHH, beginning with the complete set and repeating the procedure after eliminating from the constraints list each group of hydrogen bonds sequentially. The superimposition of the 10 resulting structures, when the subset of hydrogen bonds whose amide protons have ΔGex < 2.5 kcal⋅mol−1 is deleted from the constraints list, is labeled B in Fig. 3, whereas the A ensemble contains all of the hydrogen bonds. The group labeled C is obtained when the next group of protons (Y15 and others) is also eliminated. Ensemble D only retains hydrogen bonds whose donors are amide protons of residues W42, V44, V46, and V53. These four hydrogen bonds are intact in A, B, C, and D ensembles and only exchange when the protein is fully open. In contrast, M25 is protected only in the ensemble A and is broken in B, C, D, and U ensembles. B embraces conformations with a very flexible RT loop. The anchor of this loop with the distal hairpin is lost in C, the RT loop is still freer to move and departs from its original position; also the termini and the other two loops (n-Src and BHH) have a high rms deviation relative to the SHH model structure (structure color ranges from blue to yellow depending on this deviation). Most interestingly, D contains largely unfolded conformations, with a closed, although breathing, BHH + distal hairpin. The HX method does not give any information about the order of events connecting the observed partially unfolded forms (equilibrium data cannot define a kinetic sequence, ref. 20); however, based on the proportion of ordered amino acids found in the different groups, it looks reasonable to consider forms A, B, and C as part of F. They are more ordered than the main ‡ for folding (1), whereas conformations grouped in D are sufficiently unordered to consider them as part of the denatured ensemble, but distinguishable from U; i.e., it can be regarded as an I state.

Figure 3.

Urea dependence of ΔGex for hydrogen-bonded amide proton probes of SHH at pD 3.0. Four colors, from red to yellow, are used, depending on protection. Three protons in the distal hairpin, 44, 42, and 53, coincide with the global unfolding isotherm. Protection decreases advancing toward the β-turn region; residues 46 and 2′ show slightly lower stability. Strands flanking the long RT loop (residues 9–13 and 31–34) converge to ΔGex values 0.6 kcal⋅mol−1 lower than global unfolding. Residues within the RT loop reflect a much lower stability in the whole 0–3 M urea range. (Left) Ensembles of fully or partially folded SHH conformations coexist in equilibrium under native conditions, calculated according to HX data. Colored circles indicate the group of protons protected in each ensemble. Structures are colored according to the rms deviation with respect to folded SHH model structure.

Comparison of Exchange Behavior Between SHH and SHA.

One possible situation that could arise in the elongation experiment is the appearance of an intermediate that contains a partially folded BHH + distal β-hairpin, whereas the N and C termini, belonging to the SH3 domain are completely unstructured, i.e., the low contact order (21) β-hairpin folds much faster (22) and accumulates until folding resumes. If this were the case, highly protected hydrogen-bonded protons in the distal hairpin would exhibit a high ΔGex linearly dependent on [urea] as if I does not exist; I behaves as N for these probes. Those residues in the N and C extensions from the BHH nucleus would show a lower ΔGex, with curved urea dependence, as happens with the effective stability calculated from fluorescence experiments. As many protons are not completely protected in F and/or they suffer partial openings, the curvature in ΔGex does not guarantee that a proton is solvent exposed in I.

Protein mutations can also be used, instead of increasing denaturant concentration, to alter the extent to which the different conformational ensembles are populated, providing another way of examining the influence of intermediates in HX behavior. The kint constant will be the same for all residues in SHH and SHA apart from I2′ and V4′. The change in the free energy of exchange ΔΔGex, can be determined by:

|

where k and k

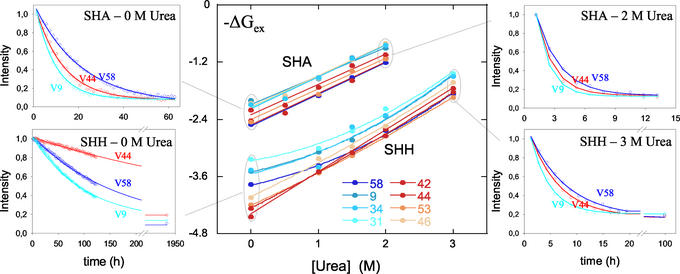

and k are the exchange rates of a given proton in SHH and SHA, respectively (23, 24). The value for ΔΔGex of globally exchanging residues should give an accurate measurement of the global effect of mutation. Fig. 4 shows the ΔGex values at the residue level, obtained in the absence of denaturant for both mutants, as well as ΔΔGex obtained as indicated above (ΔΔGex of SHH at 3 M relative to 0 M urea is also represented). Unlike SHH and like WT (25), amide protons within the five SHA β-strands show similar protection. As a consequence, among the most protected protons, those in the first, second, and fifth strands exhibit ΔΔGex values in the range of 1–1.5 kcal⋅mol−1, whereas residues in the third and fourth strands (BHH + distal hairpin) show ΔΔGex values close to 2 kcal⋅mol−1. These differences with SHH are not limited to the inserted BHH region (shown in gray in Fig. 4) but also extend to the complete distal hairpin. These data are in accordance with the population of an intermediate in SHH whose structure is similar to the one depicted in the superimposition labeled D in Fig. 3 and that is unstable in SHA. It could be argued that this differential ΔΔGex is caused by a local stabilization; i.e., the long hairpin could breathe more vigorously in SHA (and the short distal hairpin in WT) than in SHH. In that case, the observed discrepancy would be caused by the different dynamics within F and not by a preservation of local structural within the denatured collection. This latter possibility is not confirmed by the ΔGex dependence with [urea] for both mutants. Fig. 5 shows this dependence for eight protons in SHH and SHA. Four of these (W42, V44, V46, and V53) are located in the distal hairpin and should be protected in F and I, whereas those of V9, L31, L34, and V58 are in the first, second, and fifth strands with high protection in F, but exposed in I. As mF-U values are similar for the two proteins (F destabilizes likewise versus [urea]) the ΔΔGex values should remain unchanged in the whole range of [urea] if the effect were caused by fluctuations of F. On the contrary, if the differences are to be assigned to the population of an intermediate in SHH, which is absent in SHA, ΔGex should curve to lower values, as a function of I population, for those protons exchanging in this partially folded form. This is exactly what is observed. The gradient of ΔGex obtained for the four protons in SHH and SHA at high denaturant concentrations is identical, but diverges when I is significantly populated in SHH at low urea concentrations. Those residues that are protected in I (W42 and V44) retain maximal protection in SHH in the absence of denaturant, i.e., only exchange in U. On the other hand, V9 and V58 amide protons exchange freely in both U and I and deviate from maximal protection at lower urea values. Fig. 5 shows that when I is populated, e.g., SHH at 0 M urea, the proton showing slower exchange kinetics is V44; when I is destabilized, either by urea or mutation, V58 is the slowest exchanging proton.

are the exchange rates of a given proton in SHH and SHA, respectively (23, 24). The value for ΔΔGex of globally exchanging residues should give an accurate measurement of the global effect of mutation. Fig. 4 shows the ΔGex values at the residue level, obtained in the absence of denaturant for both mutants, as well as ΔΔGex obtained as indicated above (ΔΔGex of SHH at 3 M relative to 0 M urea is also represented). Unlike SHH and like WT (25), amide protons within the five SHA β-strands show similar protection. As a consequence, among the most protected protons, those in the first, second, and fifth strands exhibit ΔΔGex values in the range of 1–1.5 kcal⋅mol−1, whereas residues in the third and fourth strands (BHH + distal hairpin) show ΔΔGex values close to 2 kcal⋅mol−1. These differences with SHH are not limited to the inserted BHH region (shown in gray in Fig. 4) but also extend to the complete distal hairpin. These data are in accordance with the population of an intermediate in SHH whose structure is similar to the one depicted in the superimposition labeled D in Fig. 3 and that is unstable in SHA. It could be argued that this differential ΔΔGex is caused by a local stabilization; i.e., the long hairpin could breathe more vigorously in SHA (and the short distal hairpin in WT) than in SHH. In that case, the observed discrepancy would be caused by the different dynamics within F and not by a preservation of local structural within the denatured collection. This latter possibility is not confirmed by the ΔGex dependence with [urea] for both mutants. Fig. 5 shows this dependence for eight protons in SHH and SHA. Four of these (W42, V44, V46, and V53) are located in the distal hairpin and should be protected in F and I, whereas those of V9, L31, L34, and V58 are in the first, second, and fifth strands with high protection in F, but exposed in I. As mF-U values are similar for the two proteins (F destabilizes likewise versus [urea]) the ΔΔGex values should remain unchanged in the whole range of [urea] if the effect were caused by fluctuations of F. On the contrary, if the differences are to be assigned to the population of an intermediate in SHH, which is absent in SHA, ΔGex should curve to lower values, as a function of I population, for those protons exchanging in this partially folded form. This is exactly what is observed. The gradient of ΔGex obtained for the four protons in SHH and SHA at high denaturant concentrations is identical, but diverges when I is significantly populated in SHH at low urea concentrations. Those residues that are protected in I (W42 and V44) retain maximal protection in SHH in the absence of denaturant, i.e., only exchange in U. On the other hand, V9 and V58 amide protons exchange freely in both U and I and deviate from maximal protection at lower urea values. Fig. 5 shows that when I is populated, e.g., SHH at 0 M urea, the proton showing slower exchange kinetics is V44; when I is destabilized, either by urea or mutation, V58 is the slowest exchanging proton.

Figure 5.

A comparison of the urea dependence of ΔGex at pD 3.0 for some amide probes: in red W42, V44, V46, and V53 within the BHH + distal hairpin, and in blue V9, L31, L34, and V58 outside this nucleus (Center). Corresponding exchange time course of the three indicated protons for both SHH and SHA in lowest (Left) and highest (Right) urea concentrations are shown.

Correlation with Folding Kinetics.

ΔGI-U calculated from folding kinetics is ≈−1 kcal⋅mol−1 whereas differences in ΔΔGex between residues protected and not protected in I are ≈−0.5 kcal⋅mol−1. This discrepancy is maintained in the whole range of denaturant concentrations; whereas ΔGex vs. [urea] of protected protons perfectly coincide with ΔGU-F calculated from the kinetics analysis, no proton is found that coincide with the effective ΔG = [U] + [I]/[F] vs. [urea] isotherm, expected for protons unprotected in I. ΔG

= [U] + [I]/[F] vs. [urea] isotherm, expected for protons unprotected in I. ΔG is obtained from the ratio of the effective rate constant for refolding and the estimated unfolding rate constant obtained by extrapolation from high urea concentration. The latter estimate could imply a large error and cause the indicated discrepancy. HX data assign, at least partly, lnk deviations to ground-state rearrangements, although it cannot be discarded that these are accompanied by adjustments in barrier profiles, because of the above-mentioned discrepancy in the ΔGI-U value calculated from both methods.

is obtained from the ratio of the effective rate constant for refolding and the estimated unfolding rate constant obtained by extrapolation from high urea concentration. The latter estimate could imply a large error and cause the indicated discrepancy. HX data assign, at least partly, lnk deviations to ground-state rearrangements, although it cannot be discarded that these are accompanied by adjustments in barrier profiles, because of the above-mentioned discrepancy in the ΔGI-U value calculated from both methods.

Discussion

Exchange methods have been able to measure protein stability (26) and detect and characterize in both kinetic and equilibrium modes partially unfolded forms (11, 12, 24, 27–34) as well as folding intermediates (35–37) of proteins. The HX method was proposed to relate the pattern of the exchange free energies, ΔGex, of amide protons under low concentrations of denaturant to the partially unfolded forms' stabilities.

Here we have applied the HX technique to identify species different from the fully folded or unfolded states in the α-spectrin SH3 domain mutant SHH. The detection of forms related to the rollover obtained in kinetic chevron plots of SHH is of special interest. If such species are detected in equilibrium, alternative explanations, e.g., a different event develops into the rate-determining step at low denaturant concentration (Fig. 1), could be discarded. The general problem is that HX in many proteins is dominated by local fluctuations that break only a few H-bonds. These forms do not show important folding intermediates, and they obscure the measurements of larger unfolding events (38). To minimize the inconvenience of the existence of exchange events occurring through local openings of F that could obscure HX results, we use here varying urea concentrations, as well as two mutants with very similar sequences, SHH and SHA, showing curved and linear chevron plots, respectively. Protons that show maximal protection in SHA at varying [urea] but exhibit curved ΔGex vs. [urea] in SHH should be unbonded in I.

At a detailed level, there appears to be a broad continuum of stabilities throughout each region, but protons can be grouped in clusters with similar ΔGex values. The analysis on the equilibrium distribution of unfolded and partly folded states on SHH (summarized in Fig. 3) distinguishes forms (different form the fully folded, A in Fig. 3, and the fully unfolded U, not depicted) that expose many loop protons but retains most of the hydrogen bonds defining the five β-strands (B and C) and conformations that have lost almost all hydrogen bonds apart from those in the distal hairpin (D). Accumulation of D conformations over the U forms should relatively increase the exchange rates of all protons except those located in the long hairpin, whereas a more global protection should be expected when U is more populated. Our data on SHH and SHA at different urea concentrations follow this behavior. Regions that are formed early in the folding reaction in SHH as part of the folding I constitute the group of slowest-exchanging protons (high φI-U values are also obtained in this hairpin). However, when I is not populated, the overall subdomain hierarchy of energies does not mirror data on the folding pathway for this protein, but is highly correlated to protein topology.

The underlying principles of protein structure need to be understood if stability is to be modulated at will. Proteins can be engineered to be more stable in vitro with few mutations, by introduction of specific bonds (39, 40) or favorable interactions (41–43). However, it has been shown that in vitro protein stabilization based on local stabilization of a secondary structural element can strengthen not only the final F state but also a small set of discrete partially folded native-like intermediates (41).

We find here that even relatively unstable (undetected in WT) intermediates can be stabilized by the insertion of a stable element of local structure upgrading a two-state folder to a more complex mechanism. Folding mechanism switches are not so unusual, nonetheless. For some polypeptides, curved chevron plots have been observed only in some variants (44, 45), members of the protein family (46), or solvent conditions (47, 48).

Protein size, although important (49), does not seem to be the key determinant for formation of the folding I in SHH (e.g., SHA). Conversely, it is the discontinuity, derived from the imbalance in secondary structural elements stabilities, in the folding process of SHH that seems to lead to the transient accumulation of distinct species containing at least a folded BHH β-hairpin. Although some additional hydrophobic contacts could appear between other protein regions with the preformed hairpin, further stabilizing it, they are probably not critical for its accumulation. The occurrence of regions with strong local favorable interactions is possibly the true feature that characterizes a multistate folder.

Alternatively, thermophilic organisms produce proteins of exceptional stability by introducing surface favorable, mainly ionic, interactions (50, 51) carefully distributed throughout the structure. Thermodynamic stability has evolved to an optimal level to fit the functional needs over the protein's physiological lifetime by preserving a fine balance of largely delocalized stabilizing interactions. Conversely, there is now growing evidence that excessive local protein stabilization can be detrimental to fast folding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Drs. M. Macías and C. Civera for help with NMR spectra acquisition.

Abbreviations

- SH3

Src homology 3

- HX

hydrogen exchange

- NH

amide hydrogen

- F

native state

- U

fully unfolded state

- ‡

transition state

- I

intermediate state

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Martinez J C, Serrano L. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:1010–1016. doi: 10.1038/14896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viguera A R, Martinez J C, Filimonov V V, Mateo P L, Serrano L. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2142–2150. doi: 10.1021/bi00174a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viguera A R, Jimenez M A, Rico M, Serrano L. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:507–521. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viguera A R, Serrano L. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:357–371. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez-Alvarado M, Kortemme T, Blanco F J, Serrano L. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveberg M, Tan Y J, Silow M, Fersht A R. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:933–943. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sánchez I E, Kiefhaber T. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takei J, Chu R A, Bai Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10796–10801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190265797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fersht A R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14121–14126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260502597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu R A, Bai Y. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:759–770. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai Y, Sosnick T R, Mayne L, Englander S W. Science. 1995;269:192–197. doi: 10.1126/science.7618079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamberlain A K, Handel T M, Marqusee S. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:782–787. doi: 10.1038/nsb0996-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Mayne L, Englander S W. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:774–778. doi: 10.1038/1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llinas M, Gillespie B, Dahlquist F W, Marqusee S. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/14956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brünger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, DeLano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Englander S W, Kallenbach N R. Q Rev Biophys. 1984;16:521–655. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sibanda B L, Thornton J M. Nature. 1985;316:170–174. doi: 10.1038/316170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fersht A R. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding. New York: Freeman; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke J, Itzhaki L S, Fersht A R. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:284–287. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plaxco K W, Simons K, Baker D. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:985–994. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton W A, Munoz V, Hagen S J, Jas G S, Lapidus L J, Henry E R, Hofrichter J. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:327–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke J, Hounslow A M, Fersht A R. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:505–513. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perrett S, Clarke J, Hounslow A, Fersht A R. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9288–9298. doi: 10.1021/bi00029a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadqi M, Casares S, Abril M A, López-Mayorga O, Conejero-Lara F, Freire E. Biochemistry. 1999;33:8899–8906. doi: 10.1021/bi990413g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huyghues-Despointes B M P, Scholtz J M, Pace N. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:910–912. doi: 10.1038/13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itzhaki L S, Neira J L, Fersht A R. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:89–98. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamberlain A K, Marqusee S. Structure (London) 1997;5:859–863. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuentes E J, Wand A J. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3687–3698. doi: 10.1021/bi972579s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuentes E J, Wand A J. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9877–9883. doi: 10.1021/bi980894o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milne J S, Xu Y, Mayne L C, Englander S W. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:811–822. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arrington C B, Teesch L M, Robertson A D. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1265–1275. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng Y, Smith D L. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:247–258. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoang L, Bédard S, Krishna M M G, Englander S W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12173–12178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152439199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raschke T M, Marqusee S. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1998;9:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(98)80088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker M J, Marqusee S. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:593–602. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauder J M, Roder H. Folding Des. 1998;3:293–301. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Englander S W. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry L J, Wetzel R. Science. 1984;226:555–557. doi: 10.1126/science.6387910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumura M, Signor G, Matthews B W. Nature. 1989;342:291–293. doi: 10.1038/342291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munoz V, Cronet P, Lopez E, Serrano L. Folding Des. 1996;1:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(96)00029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villegas V, Viguera A R, Aviles F X, Serrano L. Folding Des. 1996;1:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spector S, Wang M, Carp S A, Robblee J, Hendsch Z S, Fairman R, Tidor B, Raleigh D P. Biochemistry. 2000;39:872–879. doi: 10.1021/bi992091m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khorasanizadeh S, Peters I D, Roder H. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:193–205. doi: 10.1038/nsb0296-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bachmann A, Kiefhaber T. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:375–386. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capaldi A P, Kleanthous C, Radford S E. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:209–216. doi: 10.1038/nsb757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park S H, O′Neil K T, Roder H. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14277–14283. doi: 10.1021/bi971914+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamada D, Chiti F, Guijarro J I, Kataoka M, Taddei N, Dobson C M. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:58–61. doi: 10.1038/71259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inaba K, Kobayashi N, Fersht A R. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:219–233. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fukuchi S, Nishikawa K. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:835–843. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karshikoff A, Ladenstein R. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:550–556. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01918-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.