Abstract

Background

Overlapping sense/antisense genes orientated in a tail-to-tail manner, often involving only the 3'UTRs, form the majority of gene pairs in mammalian genomes and can lead to the formation of double-stranded RNA that triggers the destruction of homologous mRNAs. Overlapping polyadenylation signal sequences have not been described previously.

Results

An instance of gene overlap has been found involving a shared single functional polyadenylation site. The genes involved are the human alpha/beta hydrolase domain containing gene 1 (ABHD1) and Sec12 genes. The nine exon human ABHD1 gene is located on chromosome 2p23.3 and encodes a 405-residue protein containing a catalytic triad analogous to that present in serine proteases. The Sec12 protein promotes efficient guanine nucleotide exchange on the Sar1 GTPase in the ER. Their sequences overlap for 42 bp in the 3'UTR in an antisense manner. Analysis by 3' RACE identified a single functional polyadenylation site, ATTAAA, within the 3'UTR of ABHD1 and a single polyadenylation signal, AATAAA, within the 3'UTR of Sec12. These polyadenylation signals overlap, sharing three bp. They are also conserved in mouse and rat. ABHD1 was expressed in all tissues and cells examined, but levels of ABHD1 varied greatly, being high in skeletal muscle and testis and low in spleen and fibroblasts.

Conclusions

Mammalian ABHD1 and Sec12 genes contain a conserved 42 bp overlap in their 3'UTR, and share a conserved TTTATTAAA/TTTAATAAA sequence that serves as a polyadenylation signal for both genes. No inverse correlation between the respective levels of ABHD1 and Sec12 RNA was found to indicate that any RNA interference occurred.

Background

Antisense RNA-mediated regulation is widespread in bacteria [1]. Recently, computational analysis of the human and mouse transcriptome identified many potential pairs of transcripts that overlap in an antisense fashion [2-5] indicating that the regulation of gene expression by antisense could be a more common phenomenon in mammalian cells than previously thought. The number of potential gene pairs identified range from 56–144 in humans [2-4] and 93–2,431 in mouse [4,5]. From an evolutionary standpoint, one would expect strong conservation of gene pairs between man and mouse paralleling the general conservation of mRNAs between these species. The large number of gene pairs that have been identified in the mouse suggests that many more are likely to be discovered by both in silico and gene expression methods in humans.

Gene overlap increases the likelihood that mRNAs derived from complementary genes will form double-stranded RNA when both genes are transcribed simultaneously. Cells monitor the quality of their mRNAs and degrade any transcripts that are incompletely translated [6]. RNA interference (RNAi) is the process by which double-stranded RNA triggers the destruction of homologous mRNAs. Considerable attention is now being given to the use of RNAi as a potential therapeutic tool [7]. The double-stranded RNA is cut into small RNAs by double strand-specific RNases. These small RNAs subsequently guide a protein nuclease to destroy their complementary mRNA targets in a catalytic manner [8,9] leading to a reduction in the expression of that particular protein.

The function of naturally occurring antisense RNAs in eukaryotes is beginning to be understood. However, no generalisations concerning the mechanism of action can be made based on those few gene pairs that have been examined experimentally. One possible function of these antisense RNAs is to control the post-transcriptional levels of their complementary RNA by regulating their stability [10,11]. Genes can overlap in many ways; they may overlap in their 5' or 3' regions or be nested. One or both of the paired transcripts may code for a protein. A common bi-directional promoter such as that between the alpha 1 and alpha 2 type IV collagen mRNAs regulates and co-ordinates the expression of these related genes [12]. The expression of the Surfeit locus genes, Surf-1 and Surf-2 are co-ordinated [13]. The reason for their co-ordinated expression remains to be determined since they are sequence-unrelated.

Both the histidyl-tRNA synthetase gene and the N-myc oncogene have overlapping gene partners arranged in a head-to-head manner. The histidyl-tRNA synthetase gene overlaps with an antisense gene, HO3, with which it shares extensive amino acid sequence homology [14]. It is unknown whether expression interference occurs, but they do have distinct tissue expression patterns. N-myc transcripts and its antisense partner, N-cym, form an RNA-RNA duplex and their expression is co-regulated, although the function of the antisense RNA is not yet understood [15]. The B cell maturation protein gene (BCMA) is the receptor for the tumour necrosis factor family member TALL-1. Nested within its mRNA is an antisense-BCMA transcript that is co-expressed [16].

The majority of gene pairs overlap in a tail-to-tail orientation, and often involve only the 3'UTRs [3,4]. The basic fibroblast growth factor gene (bFGF) has a tail-to-tail complementary transcript encoding GFG, which is a member of the MutT family of antimutator NTPases [17]. The resulting double-stranded RNA is a substrate for adenine to inosine modification that would trigger rapid degradation of the reacting RNAs [11]. Such examples indicate that antisense RNA can exhibit both regulatory and coding capacities. Thymidylate synthase mRNA overlaps with the 3'UTR of an antisense transcript, rTSalpha, the expression of which was inversely correlated with the level of thymidylate synthase mRNA [18]. Thymidylate synthase mRNA is cleaved in a site-specific manner suggesting that it is down regulated through a natural RNA-based antisense mechanism. The thyroid hormone receptor gene, c-erbAalpha, overlaps with RevErb in a tail-to-tail orientation [19]. The c-erbAalpha gene has two isoforms and there is evidence that the expression of isoform alpha2 is negatively regulated by antisense interactions with the complementary RevErb mRNA [20]. Antisense transcripts of the epithelial Na/Pi cotransporter have no effect on transcript stability, but Pi transport activity is reduced suggesting that they interfered with the translation of the transporter mRNA [21]. The human Misshapen/NIK-related kinase and the nicotinic cholinergic receptor, epsilon polypeptide 3'UTRs overlap [22]. They possess the classical AATAAA and ATTAAA polyadenylation signal sites respectively, but these sites do not overlap. The Surfeit locus contains another example of overlapping genes. The 3'UTRs of Surf-2 and Surf-4 overlap in mouse, but not man [23]. However, the murine polyadenylation signals do not overlap. The PR264/SC35 splicing factor is a member of the SR protein family. There are many varieties of antisense transcripts, entitled ET RNAs, which overlap predominantly in the 3'UTR of PR264/SC35, of which some may be protein-encoding [24]. Single cells co-expressed both mRNAs.

The research presented here is the case of two coding transcripts, human ABHD1 and Sec12, which overlap in their 3'UTRs. In the mouse, the presence of antisense transcripts of the lung alpha/beta hydrolase-1 (ABHD1)[25] and prolactin regulatory element binding (Sec12/PREB) genes [26] has been identified by a computational search [3]. Recently, we cloned three closely related cDNAs from a murine lung cDNA library [25], the open reading frames (ORF) of which contained a predicted alpha/beta hydrolase domain [27], containing a catalytic triad analogous to that present in serine proteases, leading them to be named lung alpha/beta hydrolase (LABH1-3) fold proteins. Subsequently, their tissue distribution suggested that they were more abundant in other tissues and, in keeping with the wishes of the gene nomenclature committee; they have been designated alpha/beta hydrolase domain containing genes 1, 2 and 3 (ABHD1, ABHD2 and ABHD3). The proteins encoded by their ORFs are related to the Escherichia coli ORF YHET that belongs to the prosite UPF0017 protein family, whose function remains unknown [28].

A BLAST search of the GenBank database with the cDNA sequence of human ABHD1 revealed a 3'UTR region of similarity with rat Sec12/PREB cDNA sequence [29]. In yeast, Sec12p is involved in vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the formation of autophagosomes [30,31]. Sec12p is a type II transmembrane glycoprotein protein with a large cytosolic domain, which promotes efficient guanine nucleotide exchange on the Sar1 GTPase [30,32,33]. A recombinant part of rat Sec12, encompassing residues 175–417, has been reported as the prolactin regulatory element binding protein (PREB) transcription factor which regulates the activity of the prolactin promoter [29]. The murine PREB gene has been localised to the proximal end of chromosome 5 [26] and a partial human cDNA encoding PREB was cloned from brain and mapped to 2p23 [34]. Overall, Sec12/PREB transcripts are highly abundant in tissues that are active in secretion [29]. To investigate the nature of the shared cDNA sequences of human ABHD1 and Sec12, 3' RACE was used to clone the human homologue of murine ABHD1, the human and mouse Sec12 cDNA sequences and determine the location of the polyadenylation sites. I found that the human ABHD1 and Sec12 3'UTRs share overlapping polyadenylation signal sequences. Overlapping polyadenylation signal sequences have not been described previously in eukaryotic genomes.

Results

Human ABHD1 cDNA

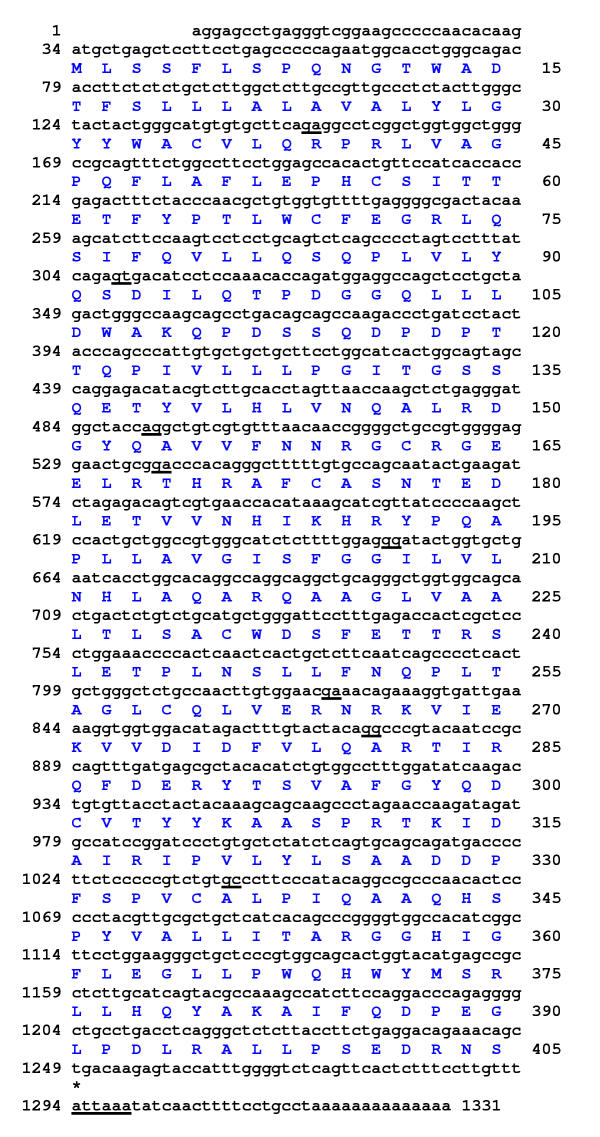

The human homologue of the murine alpha/beta hydrolase domain gene 1 (ABHD1) was cloned by 3'RACE and sequenced. The human ABHD1 1331 bp cDNA sequence has a 33 bp 5'UTR, the first ATG of the ORF is in good sequence consensus for an initiation methionine, and has a short, 69 bp, 3'UTR which includes an ATTAAA polyadenylation signal at 1294–1299 (GenBank accession No. AY033290) (Fig. 1). The ORF encodes a 405 residue predicted protein with a 45,221 Da molecular mass and an isoelectric point 5.80.

Figure 1.

The cDNA sequence and translation of human ABHD1. The exon/exon boundaries were determined by comparison with the sequence of genomic BAC clone RP11-195B17. An asterisk indicates the tga stop codon. The underlined nucleotide pairs indicate the exon/exon boundaries. There is a single polyadenylation signal (attaaa at 1294–1299) shown in bold type and underlined.

Sequence comparison of the human ABHD1 protein with other members of the prosite UPF0017 family

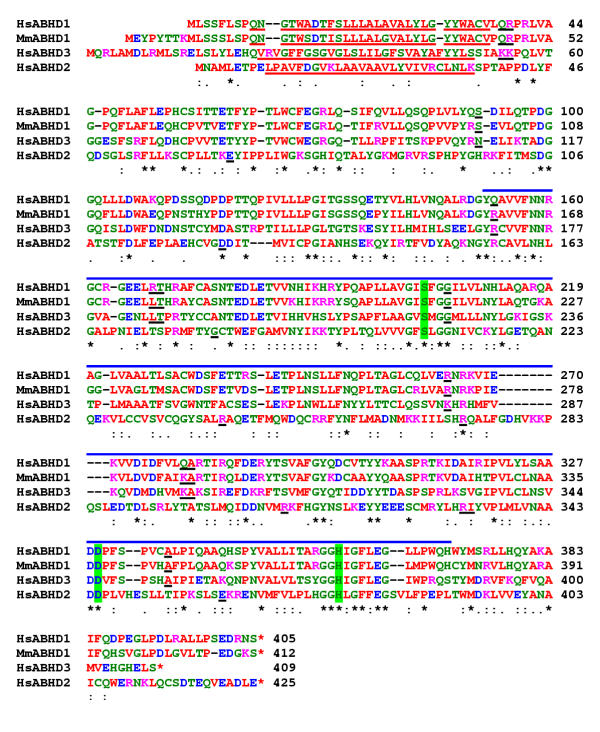

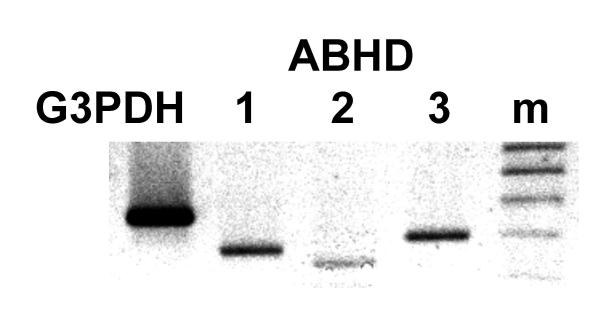

The human ABHD1 cDNA was compared with that of the mouse [25]. They are of similar length, having 81% identity at the nucleotide level. However, there is a 15 bp deletion in the human sequence in the 5' region relative to the mouse sequence. In the mouse, this region contains an initiation ATG codon that is in excellent sequence context for the start of translation. Consequently, the human protein is eight residues shorter at the NH2 terminal and has the ORF starting at the second ATG site on the corresponding mouse sequence (Fig. 2). A database search identified a porcine EST (BI184779) and a rat EST (AW916573) that have predicted starts of translations that are the same as the human and mouse proteins respectively. Overall, the human and mouse proteins have 79% identity and 96% similarity and all 8 exon/exon boundaries are conserved. The human protein has an additional serine residue inserted close to the COOH terminal. A database search of the human genome with the human ABHD1 protein sequence identified two other related genes belonging to the prosite UPF0017 family. They are the HS1-2 protein [35] that is homologous to murine protein ABHD2 and the ORF of the unnamed cDNA (AF007152)[36]. The deduced protein sequence of this unnamed cDNA (AAC19155) has been truncated to the first methionine residue by homology with murine ABHD3 [25]. A comparison of these three proteins showed that human ABHD1 is most closely related to the AAC19155/ABHD3 protein having 43% identity and 76% similarity (Fig. 2). All three proteins have single predicted amino-terminus transmembrane domains despite having very little sequence identity in this region. The central cores of the three proteins are predicted to form alpha/beta hydrolase folds. This catalytic domain is found in a very wide range of enzymes such as serine proteases. In human ABHD1, the predicted catalytic triad is Ser203, Asp329 and His358 and is conserved in all members of the prosite UPF0017 family [25]. The suggested reaction mechanism is that the sidechain group of Ser203 acts as a nucleophilic centre; His358 sidechain acts as a general base and is hydrogen bonded to the carboxylic group of Asp329 to form a charge relay system. Human ABHD1, HS1-2/ABHD2 and protein AAC19155/ABHD3 are also expressed in lung tissue (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Sequence comparison of the human and murine ABHD1 proteins with two other closely related human ABHD proteins. The species are; Homo sapiens, Hs and Mus musculus, Mm. The proteins are human ABHD1; murine ABHD1 [25]; the putative transmembrane protein, HS1-2, ABHD2 [35] and the ORF of clones 23649 and 23755, accession No. AAC19155 truncated to first methionine residue, ABHD3 [36]. The stop codons are indicated by red asterisks. The predicted amino-terminus transmembrane domains are shown underlined. The predicted alpha/beta hydrolase fold domain is shown by a continuous blue line above the alignment and the predicted catalytic triads (which on human ABHD1 it is Ser203, Asp329 and His358) are indicated in bold and highlighted in green. The locations of the exon/exon boundaries are shown on the protein sequences as underlined residues. Residues conserved in all proteins are indicated by an (*), strongly conserved residues by (:) and weakly conserved residues by (.). Residues are colour coded: basic, DE, red; acidic, KR, pink; polar, CGHNQSTY, green and hydrophobic, AFILMPVW, red.

Figure 3.

Expression of the mRNAs of three members of the prosite UPF0017 family in human lung tissue determined by RT-PCR analysis. Lane 1, the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, G3PDH; lane 2, ABHD1; lane 3, ABHD2 (HS1-2); lane 4, ABHD3, (accession AF007152); lane 5, 100 bp marker, m.

The ABHD1 and Sec12 genes overlap in an antisense manner

Intriguingly, a database search of expressed sequences with the human ABHD1 cDNA sequence identified numerous human EST sequences with homology to the rat Sec12/PREB cDNA sequence [29]. To determine nature of this shared gene homology this region was amplified by PCR from human genomic DNA using primers corresponding to the ends of a human ABHD1/Sec12 electronic contiguous sequence. The sequence of this cloned amplicon confirmed that ABHD1 and Sec12 genes overlap in an antisense manner (data not shown). Subsequently, the sequence of this region was found to match that of BAC clone RP11-195B17 (GenBank accession AC013403 Genome Sequencing Center, St. Louis, USA). To identify the extent of the gene overlap the human and murine Sec12 cDNAs were cloned by 3'RACE and sequenced and the location of their polyadenylation sites identified.

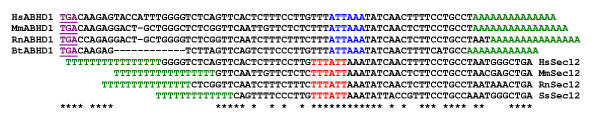

The human Sec12 2059 bp cDNA sequence has 131 bp 5'UTR; the first ATG of the ORF is in excellent sequence context for the start of translation and has a 677 bp 3'UTR which includes a single polyadenylation signal, AATAAA, at 2010–2015 (GenBank accession No. AF203687) (data not shown). The murine Sec12 1983 bp cDNA sequence has an homologous AATAAA polyadenylation signal at 1953–1958 (GenBank accession No. AF150808) (data not shown). The human ABHD1 and Sec12 cDNAs have a 42 bp overlap in their 3'UTR (Fig. 4). A conserved TTTATTAAA/TTTAATAAA sequence serves as a polyadenylation signal for both genes. The ABHD1 cDNAs have short 3'UTRs and use an ATTAAA polyadenylation signal, whilst the Sec12 cDNAs use an AATAAA polyadenylation signal. These signals are also conserved in mouse, rat, cow and pig ABHD1 and Sec12 ESTs sequences (Fig. 4). Also conserved are the sequences adjacent to the common ABHD1 and Sec12 polyadenylation sites suggesting that they may be important recognition sites for pre-mRNA cleavage factors. In the human and mouse ABHD1 mRNAs, the 3'UTR region upstream of the polyadenylation signals is more uracil rich (37–40%) than the expected 30% average for a 3'UTR [37] suggesting that this region may harbour upstream sequence elements involved in polyadenylation.

Figure 4.

Conservation and shared usage of a polyadenylation signal sequence by mammalian ABHD1 and Sec12 cDNAs. The stop codons of ABHD1 transcripts are shown in purple. The 3'UTRs of human, Homo sapiens (Hs); mouse, Mus musculus (Mm); rat, Rattus norvegicus (Rn); cow, Bos taurus (Bt) and pig, Sus scrofa (Ss) ABHD1 and Sec12 cDNAs were aligned. For clarity, the complementary and reversed Sec12 sequences are shown. The ABHD1 polyadenylation signal is ATTAAA, coloured blue and the Sec12 signal is AATAAA (TTTATT, coloured red). The polyadenylic acid tails are shown in green. The accession numbers are: HsABHD1, AY033290; HsSec12, AF203687; MmSec12, AF150808 (all this study); Mm ABHD1, AF189764 [25]; RnSec12 cDNA, BI300647; RnSec12, EST BE100313; BtABHD1, EST BI541180 and SsSec12 EST, AW785453. The conserved nucleotides are indicated (*).

The cDNA sequence of the human Sec12/PREB gene has previously been reported [34]. However, nucleotide cytidine-186 is thymidine in their sequence and this alters the deduced amino acid sequence from a leucine to a phenylalanine at residue 19. Leucine-19 is conserved in mouse, rat and Caenorhabditis elegans Sec12/PREB proteins. The mouse Sec12/PREB cDNA sequence has been previously reported [26]. However, the ORF reported here differs by the inclusion of an inserted glycine-136 residue. Glycine-136 is conserved in the human and rat homologues [29,34].

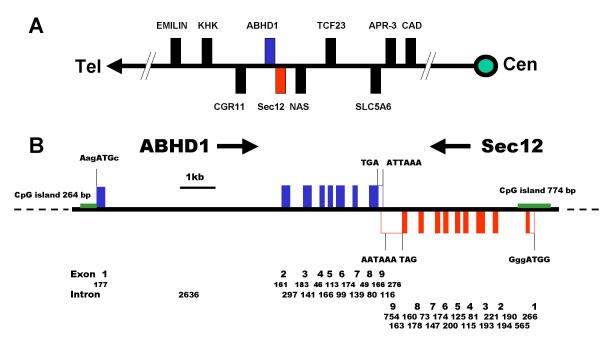

Human ABHD1 and Sec12 genes

Previously, the human PREB gene was mapped to chromosome 2p23 [34]. A BLAST search of the human genome identified the location of the ABHD1 and Sec12 genes as 2p23.3, being encoded on opposite strands. They are flanked by the cell growth regulatory with EF-hand domain gene, CGR11 in the telomeric direction and by the NAS hypothetical protein, LOC165086, in the centromeric direction (Fig. 5A). Both are nine exon genes, the ABHD1 gene spans 6.9 kb and the Sec12 gene spans 3.8 kb (Fig. 5B). All splice donor/acceptor sites contained consensus GT/AT dinucleotides. Both ABHD1 and Sec12 have CpG islands in their promoter regions, such islands being one of the characteristics of housekeeping genes [38]. The ABHD1 gene has a short CpG island (264 bp, 72% GC) 5' of and encompassing part of exon 1 and the Sec12 gene has a longer CpG island (774 bp, 71% GC) spanning exon 1. The genes for HS1-2/ABHD2 and ABHD3 are much longer than ABHD1 and are located on different chromosomes. The 107 kb ABHD2 gene is located at 15q26.1 and the 54 kb ABHD3 gene is located at 18q11.1 close to the centromere.

Figure 5.

Chromosomal localisation and structures of the ABHD1 and Sec12 genes. (A) The human ABHD1 and Sec12 genes are at locus 2p23.3 on opposite strands. Genes encoded on + strand are shown above the line. They are flanked by the elastin microfibril interface located protein, EMILIN; ketohexokinase or fructokinase, KHK; cell growth regulatory with EF-hand domain, CGR11; solute carrier family 5 (sodium-dependent vitamin transporter) member 6 in the telomeric direction and by the NAS hypothetical protein, LOC165086; transcription factor 23, TCF23; SLC5A6; apoptosis related protein, APR-3 and the trifunctional protein of pyrimidine biosynthesis, carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2, aspartate transcarbamylase, and dihydroorotase, CAD genes in the centromeric direction. Genes orientated in the opposite direction to ABHD1 are shown below the line. (B) The gene structures of the ABHD1 and Sec12 genes. The human genomic sequence corresponding to these two cDNAs is located on BAC clone RP11-195B17 and both genes have nine exons and CpG islands. The ORF is indicated by closed boxes. The sequences around the initiation methionine codons are shown, as are the stop codons and the polyadenylation sites. The size of the exons and introns are indicated.

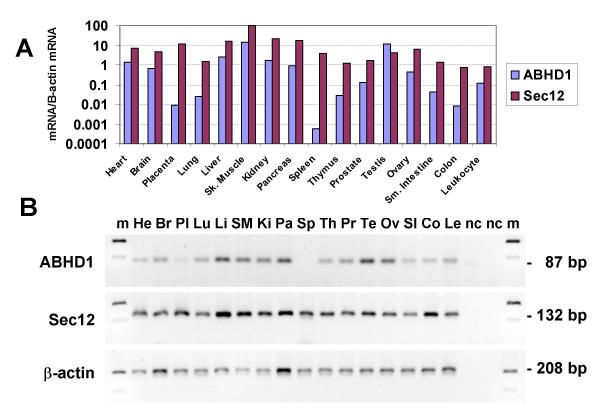

Tissue and cellular distribution of human ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA

The expression of the ABHD1 and Sec12 genes in different adult tissues relative to the expression of the housekeeping gene, β-actin, was examined by real time PCR (Fig. 6A). Both genes were expressed in all tissues examined, being highest in skeletal muscle, but the expression level of β-actin/μg cDNA was low in skeletal muscle relative to all the other tissues examined. The expression of ABHD1 in spleen was detectable by SYBR green fluorescence, but was below the level of detection by ethidium bromide agarose gel electrophoresis after 40 cycles (Fig. 6B). The expression level of ABHD1 was, on average, about 7% that of Sec12. However, in testis the expression of ABHD1 was greater than Sec12. In the steady-state situation in tissues, there was a positive correlation (r= 0.73) between the expression of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA relative to the expression of β-actin and not an inverse correlation, which would have suggested that RNA interference occurred.

Figure 6.

Expression of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNAs in human adult tissues by semiquantitative real time PCR. (A) Expression levels in each tissue cDNA were normalised to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene β-actin. The ratios of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA/β-actin mRNA (Y axis, arbitrary units) from each tissue were standardised to that of Sec12 expression in skeletal muscle, which was taken as 100. (B) Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel of PCR products after 40 cycles of amplification. The tissues examined were: heart, He; whole brain, Br; placenta, Pl; lung, Lu; liver, Li, skeletal muscle, SM, kidney, Ki, pancreas, Pa; spleen, Sp; thymus, Th; prostate, Pr, testis, Te, ovary, Ov, small intestine, SI, colon, Co; peripheral blood leukocyte, Le; and no cDNA control, -c; 100 bp ladder, m.

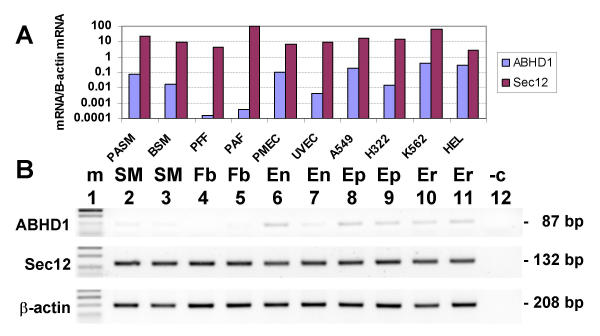

ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNAs were expressed in all cultured cell types examined, being found in smooth muscle, fibroblasts, endothelial, epithelial and blood cell types (Fig. 7A and 7B). The expression of ABHD1 in fibroblasts was notably low relative to other cell types. On average, the expression level of ABHD1 was 1.4% that of Sec12. In the cell types, there was no correlation between the expression of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA.

Figure 7.

Expression of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNAs in human cell types by semiquantitative real time PCR. (A) Expression levels in each cell type cDNA were normalised to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene β-actin. The ratios of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA/β-actin mRNA (Y axis, arbitrary units) from each cell type were standardised to that of Sec12 expression in pulmonary adult fibroblasts, which was taken as 100. (B) Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel of PCR products after 40 cycles of amplification. The lanes are: 1, phiX174 DNA/HaeIII markers (m); 2, pulmonary artery smooth muscle (SM); 3, bronchial smooth muscle (SM); 4, HFL-1 (pulmonary foetal fibroblasts) (Fb); 5, pulmonary adult fibroblasts (Fb); 6, placental microvascular endothelial (En); 7, umbilical vein endothelial (En); 8, A549 (adenocarcinoma alveolar epithelial) (Ep); 9, H322 (adenocarcinoma bronchial epithelial) (Ep); 10, HEL (erythroleukemia) (Er); 11, K562 (erythroleukemia) (Er); 12, negative control (-c).

Discussion

The human ABHD1 and Sec12 genes contain a short conserved overlapping region in their 3'UTR, and share 3 base pairs (ATT/AAT) in their polyadenylation signal sequences, a novel feature that has not been identified previously in the human genome. This feature has been found also in two other mammals. The homologues of human ABHD1 and Sec12 do not overlap and are not linked in the genomes of the fish, Takifugu rubripes; fly, Drosophila melanogaster; mosquito, Anopheles gambiae and the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. A single 3' RACE PCR amplicon was seen after agarose gel electrophoresis for both the human and mouse ABHD1 and Sec12 gene transcripts, indicating that a single polyadenylation signal only is utilised and alternative splicing in both genes is absent. The Sec12/PREB gene transcript was suggested previously to display alternative splicing since most tissues yielded two bands of 2.2 and 1.5 kb on northern blots [29]. However, the lower band is probably due to hybridisation of the Sec12/PREB cDNA probe to the 3'UTR of the ABHD1 transcript.

Overlapping genes are often functionally and/or structurally related and may regulate each others expression by a natural antisense mechanism. Although Sec12 and ABHD1 proteins do not share any sequence homology, it is possible that they could be functionally related. In this regard, it is of interest to note that both Sec12 and ABHD1 have a single transmembrane domain. Sec12 is located in the ER and it is possible that this is the location of ABHD1 also.

If both genes in a gene pair are transcribed simultaneously, the complementary regions in their mRNAs could possibly meet and form double-stranded RNA. Any such double-stranded RNA is liable to be mistaken for viral DNA, leading to the destruction of the double-stranded RNA and homologous mRNAs by the cell's antiviral defence mechanism [39]. This may provide an evolutionary pressure to avoid such regions of gene overlap, unless the formation of double-stranded RNA is one mechanism by which gene translation may be regulated. However, when the chromosomal rearrangement in the common ancestor of man and rodents that, perchance, brought the ABHD1 and Sec12 genes together occurred, the rearrangement became "locked-in" since evolutionary pressure has selected to maintain this polyadenylation site. A mutation in this polyadenylation site would be potentially hazardous, resulting in loss of the correct processing of both mRNAs. In this regard, it is of interest to note that the next classical polyadenylation signal site that could be utilised by Sec12 transcripts is 11.5 kb downstream, beyond the ABHD1 gene. However, there are classical polyadenylation signal sites within introns 8 and 6 of the Sec12 gene that could be utilised by longer ABHD1 transcripts. Both genes appear to have housekeeping roles and loss of one or both would be detrimental to survival. Sec12 is a housekeeping gene in the secretory pathway [32] being expressed in all tissues and cells examined. It has no other closely related paralogs in the genome that could take over its cellular role if Sec12 transcripts were lost. The human ABHD1 protein may have an enzymatic function such as an esterase, lipase or thioesterase. It is evolutionarily conserved, being found in bacteria such as E.coli, suggesting an important housekeeping role for the enzyme. It is expressed in a wide range of tissues and cells, although its expression level varied greatly. However, it is one of three related genes in the genome, being most closely related to ABHD3. It remains to be determined whether ABHD2 and ABHD3 could take over the cellular role of ABHD1 if the ABHD1 gene was lost.

Although both ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNAs were cloned from human lung cDNA, they were expressed in all adult tissues and cell types examined. The expression level of ABHD1 was generally 7% that of Sec12. ABHD1 levels were highest in skeletal muscle, testis and liver, but over a thousand-fold lower in spleen and fibroblasts. A similar tissue expression pattern for ABHD1 has been found in mice [25]. The reasons for the wide variation in expression are not known. However, the expression of ABHD1 was greater than Sec12 in testis, which suggests that ABHD1 may have an important role in this organ. The level of expression of Sec12 was more constant between tissues and cells types, varying less than a hundred-fold.

The expression of steady-state ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA in both tissues and cells showed that these two genes are co-expressed in a spatial manner. However, their expression may be separated in a temporal manner. There was no evidence of an inverse correlation between the respective levels of both RNA species that would be expected if RNA interference were occurring. However, antisense transcripts may not affect mRNA stability, but may interfere with translation [21]. It remains to be determined whether the formation of double-stranded RNA occurs and if there is an inverse correlation in ABHD1 and Sec12 protein levels.

Conclusions

The human ABHD1 cDNA encodes a deduced protein of 405 residues predicted to contain an amino-terminus transmembrane domain and a carboxy-terminus alpha/beta hydrolase fold. The ABHD1 gene maps to chromosome 2p23.3. ABHD1 has characteristics of a housekeeping gene, possessing a 5' CpG island and being expressed in all tissues and cells examined. The ABHD1 and the Sec12 cDNAs overlap in a tail-to-tail manner in their 3'UTR, and share overlapping polyadenylation signal sequences. There was no inverse correlation between the respective levels of both RNA species to indicate that RNA interference had occurred.

Methods

Molecular cloning of human ABHD1 and human and mouse Sec12 cDNAs

The mouse ABHD1 cDNA sequence [25] was used in a BLAST search of the human genome sequence to identify the location of the human ABHD1 gene. The genomic BAC clone RP11-195B17 was identified as the likely location of the gene. From the sequence of the BAC clone a PCR primer, AGGAGCCTGAGGGTCGGAAGCCCC (Amersham-pharmacia Biotech, UK), located at the 5' end of the cDNA, was designed and used to clone the human ABHD1 cDNA by 3' RACE from RACE ready lung cDNA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech, UK). To investigate the nature of the complementary cDNA sequences of human ABHD1 with Sec12, 3' RACE analysis was used to clone the human and mouse Sec12 cDNA sequences and determine the location of the polyadenylation sites. Human and mouse Sec12 electronic contiguous sequences were generated from EST sequences homologous to the rat Sec12/PREB cDNA sequence [29]. PCR primers, GTGTGAGAGGGGTAGGGAGTGCTCCCG and CAAGTCCAGTGCTGAGAGGGGTCGGC were designed from the 5' end of the Sec12 electronic contiguous sequences of human and mouse respectively. Utilising these primers clones encoding the human and mouse Sec12 cDNA sequences were obtained by 3' RACE from lung cDNAs. RACE-PCR was carried out in a PE2400 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, UK) using Advantage cDNA polymerase (Clontech). PCR products were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. PCR products were cloned and sequenced as previously described [40].

The expression of the ABHD1, ABHD2 and ABHD3 mRNA in lung tissue

Total RNA was extracted from lung tissue using guanidine thiocyanate and treated with DNase-I to remove any contaminating genomic DNA (Total RNA isolation system, Promega, UK). Total RNA was reverse transcribed with AMV RNase H-reverse transcriptase (ThermoScript, Life Technologies, UK) using an oligo-dT primer. The cDNA was amplified by PCR with an annealing temperature of 60°C using the PCR primers for: G3PDH, GGAAATCCCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAGC and GGCCATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTC producing a 486 bp amplicon; ABHD1, CGTGGGCATCTCTTTTGGAGGGATAC and CACAGACGGGGGAGAAGGGGTCAT producing a 410 bp amplicon; ABHD2 (HS1-2), GATCCGTTGGTGCATGAAAGTCTTCT and CATCTCCCTCAGTGACCTGGATCTGA producing a 347 bp amplicon and ABHD3 (AF007152), TTCACTTCAGTCATGTTTGGATACCA and CCATCTGCTGGCTTATTTGCTTTAT producing a 416 bp amplicon. PCR products were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide.

Tissue and cellular distribution of human ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA by real time PCR

Human cDNA was analysed for the relative expression of the ABHD1, Sec12 and β-actin mRNA by real time PCR. The 16 adult tissue cDNAs (Clontech, UK) were generated from polyA+ selected RNA and reverse transcribed using an oligo-dT primer. The 10 cell type cDNAs were generated from total RNA and reverse transcribed using random hexamers. PCR was carried out on a GeneAmp 5700 Sequence Detection System using a SYBR Green I double-stranded DNA binding dye assay (both from AB Applied Biosystems). Approximately 4 ng of cDNA from each tissue, and cDNA derived from 50 ng of total RNA from each cell type was amplified by PCR using Taq Gold polymerase. Tissue and cellular master mixes were divided into gene specific mixes with the addition of PCR primers to a final concentration of 200 μM. The primers were: ABHD1, CCAAGATAGATGCCATCCGGA (exon 8) and CCTGTATGGGAAGGGCACAGA (exon 8/9) producing a 87 bp amplicon; Sec12, GATGTGGCCTTTCTACCTGAGAAG (exon 8) and CACAGGAACACTCCGCCGT (exon 8/9) producing a 132 bp amplicon and β-actin, GGCCACGGCTGCTTC and GTTGGCGTACAGGTCTTTGC producing a 208 bp amplicon. The amplification conditions were; a 10 min hot start to activate the polymerase followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The number of cycles required for the SYBR Green I dye fluorescence to become significantly higher than background fluorescence (termed cycle threshold [Ct]) was used as a measure of abundance. An average Ct value was determined for each sample. A comparative Ct method was used to determine gene expression. Expression levels in each tissue and cell type cDNA sample were normalised to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene β-actin (ΔCt). The ratios of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA/β-actin mRNA from each tissue were standardised to that of Sec12 expression in skeletal muscle, which was taken as 100% (ΔΔCt). For the cell types, the ratios of ABHD1 and Sec12 mRNA/β-actin mRNA were standardised to that of Sec12 expression in pulmonary adult fibroblasts which was taken as 100%. The formula 2-ΔΔCt was used to calculate relative expression levels assuming a doubling of the DNA template per PCR cycle. Amplification specificity was confirmed by melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Bioinformatics

Sequence database searches were carried out using BLAST 2.0 [41]. Protein multiple sequence alignments were carried out with the aid of the programme CLUSTAL W using the default parameters [42]. Transmembrane domains were predicted using CoPreTHi [43]. The prediction of the alpha/beta hydrolase fold domain and its catalytic triad were carried out using 3D-PSSM version 2.6.0 [44] as previously described [25].

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

I thank Lisa Lowery for DNA sequencing, Athina Milona for assistance with the real time PCR, June Edgar and the reviewers for their constructive comments on this paper.

References

- Wagner EG, Altuvia S, Romby P. Antisense RNAs in bacteria and their genetic elements. Adv Genet. 2002;46:361–398. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(02)46013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey ME, Moore TF, Higgins DG. Overlapping antisense transcription in the human genome. Comp Functional Genomics. 2002;3:244–253. doi: 10.1002/cfg.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner B, Williams G, Campbell RD, Sanderson CM. Antisense transcripts in the human genome. Trends Genet. 2002;18:63–65. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shendure J, Church GM. Computational discovery of sense-antisense transcription in the human and mouse genomes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:research0044. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-9-research0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki Y, Furuno M, Kasukawa T, Adachi J, Bono H, Kondo S, Nikaido I, Osato N, Saito R, Suzuki H, et al. Analysis of the mouse transcriptome based on functional annotation of 60,770 full-length cDNAs. Nature. 2002;420:512–514. doi: 10.1038/nature01266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mango SE. Stop making nonSense: the C. elegans smg genes. Trends Genet. 2001;17:646–653. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkhardt A. Blocking oncogenes in malignant cells by RNA interference-New hope for a highly specific cancer treatment? Cancer Cell. 2002;2:167–168. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, Zamore PD. RNAi: nature abhors a double-strand. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:225–232. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura K. A short primer on RNAi: RNA-directed RNA polymerase acts as a key catalyst. Cell. 2001;107:415–418. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq M, Hildebrandt M, Maniak M, Nellen W. Developmental regulation of antisense-mediated gene silencing in Dictyostelium. Antisense Res Dev. 1994;4:263–267. doi: 10.1089/ard.1994.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelman D, Kirschner MW. An antisense mRNA directs the covalent modification of the transcript encoding fibroblast growth factor in Xenopus oocytes. Cell. 1989;59:687–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila P, Soininen R, Tryggvason K. Directional regulatory activity of cis-acting elements in the bidirectional alpha 1(IV) and alpha 2(IV) collagen gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24677–24682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K, Fried M. CpG methylation and the binding of YY1 and ETS proteins to the Surf-1/Surf-2. Gene. 1995;157:257–259. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00120-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hanlon TP, Raben N, Miller FW. A novel gene oriented in a head-to-head configuration with the human histidyl-tRNA synthetase (HRS) gene encodes an mRNA that predicts a polypeptide homologous to HRS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:556–566. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal GW, Armstrong BC, Battey JF. N-myc mRNA forms an RNA-RNA duplex with endogenous antisense transcripts. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4180–4191. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laabi Y, Gras MP, Brouet JC, Berger R, Larsen CJ, Tsapis A. The BCMA gene, preferentially expressed during B lymphoid maturation, is bidirectionally transcribed. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1147–1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.7.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AW, Too CK, Murphy PR. The basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) antisense RNA (GFG) is translated into a MutT-related protein in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;223:19–23. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Dolnick BJ. Natural antisense (rTSalpha) RNA induces site-specific cleavage of thymidylate synthase mRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1587:183–193. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4439(02)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar MA, Hodin RA, Cardona G, Chin WW. Gene expression from the c-erbA alpha/Rev-ErbA alpha genomic locus. Potential regulation of alternative splicing by opposite strand transcription. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12859–12863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings ML, Milcarek C, Martincic K, Peterson ML, Munroe SH. Expression of the thyroid hormone receptor gene, erbAalpha, in B lymphocytes: alternative mRNA processing is independent of differentiation but correlates with antisense RNA levels. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4296–4300. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A, Preston-Fayers K, Dehmelt L, Nalbant P. Regulation of the NPT gene by a naturally occurring antisense transcript. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2002;36:241–252. doi: 10.1385/CBB:36:2-3:241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan I, Watanabe NM, Kajikawa E, Ishida T, Pandey A, Kusumi A. Overlapping of MINK and CHRNE gene loci in the course of mammalian evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2906–2910. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhig T, Ruhrberg C, Mor O, Fried M. The human Surfeit locus. Genomics. 1998;52:72–78. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sureau A, Soret J, Guyon C, Gaillard C, Dumon S, Keller M, Crisanti P, Perbal B. Characterization of multiple alternative RNAs resulting from antisense transcription of the PR264/SC35 splicing factor gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4513–4522. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar AJ, Polak JM. Cloning and tissue distribution of 3 murine alpha/beta hydrolase fold protein cDNAs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;292:617–625. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Clelland CL, Craciun L, Bancroft C, Lufkin T. Mapping and developmental expression analysis of the WD-repeat gene Preb. Genomics. 2000;63:391–399. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist M. Alpha/Beta-hydrolase fold enzymes: structures, functions and mechanisms. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2000;1:209–235. doi: 10.2174/1389203003381405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Godzik A, Skolnick J, Fetrow JS. Functional analysis of the Escherichia coli genome for members of the alpha/beta hydrolase family. Fold Des. 1998;3:535–548. doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(98)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliss MS, Hinkle PM, Bancroft C. Expression cloning and characterization of PREB (prolactin regulatory element binding), a novel WD motif DNA-binding protein with a capacity to regulate prolactin promoter activity. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:644–657. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.4.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano A, Brada D, Schekman R. A membrane glycoprotein, Sec12p, required for protein transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:851–863. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.3.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N, Hamasaki M, Yokota S, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Kihara A, Yoshimori T, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Autophagosome requires specific early Sec proteins for its formation and NSF/SNARE for vacuolar fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3690–3702. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Enfert C, Barlowe C, Nishikawa S, Nakano A, Schekman R. Structural and functional dissection of a membrane glycoprotein required for vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5727–5734. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman T, Plutner H, Balch WE. The Mammalian Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor mSec12 is Essential for Activation of the Sar1 GTPase Directing Endoplasmic Reticulum Export. Traffic. 2001;2:465–475. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.20704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Clelland CL, Levy B, McKie JM, Duncan AM, Hirschhorn K, Bancroft C. Cloning and characterization of human PREB; a gene that maps to a genomic region associated with trisomy 2p syndrome. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:675–681. doi: 10.1007/s003350010142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapiejko PJ, George ST, Malbon CC. Primary structure of a human protein which bears structural similarities to members of the rhodopsin/beta-adrenergic receptor family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:8721. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.17.8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Andersson B, Worley KC, Muzny DM, Ding Y, Liu W, Ricafrente JY, Wentland MA, Lennon G, Gibbs RA. Large-scale concatenation cDNA sequencing. Genome Res. 1997;7:353–358. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre M, Gautheret D. Sequence determinants in human polyadenylation site selection. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-7. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/4/7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale ST, Baltimore D. The "initiator" as a transcription control element. Cell. 1989;57:103–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR. RNA interference: antiviral defense and genetic tool. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:597–599. doi: 10.1038/ni0702-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar AJ, Polak JM. The human homologues of yeast vacuolar protein sorting 29 and 35. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:622–630. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promponas VJ, Palaios GA, Pasquier CM, Hamodrakas JS, Hamodrakas SJ. CoPreTHi: a Web tool which combines transmembrane protein segment prediction methods. In Silico Biol. 1999;1:159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LA, MacCallum RM, Sternberg MJE. Enhanced Genome Annotation using Structural Profiles in the Program 3D-PSSM. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:499–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]