Abstract

In this study reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) has been used to identify mt1 and MT2 receptor mRNA expression in the rat tail artery. The contributions of both receptors to the functional response to melatonin were examined with the putative selective MT2 receptor antagonists, 4-phenyl-2-propionamidotetraline (4-P-PDOT) and 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine. In addition, the action of melatonin on the second messenger cyclic AMP was investigated.

Using RT–PCR, mt1 receptor mRNA was detected in the tail artery from seven rats. In contrast MT2 receptor mRNA was not detected even after nested PCR.

At low concentrations of the MT2 selective ligands, neither 10 nM 4-P-PDOT (pEC50=8.70±0.31 (control) vs 8.73±0.16, n=6) nor 60 nM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine (pEC50=8.53±0.20 (control) vs 8.83±0.38, n=6) significantly altered the potency of melatonin in the rat tail artery.

At concentrations non-selective for mt1 and MT2 receptors, 4-P-PDOT (3 μM) and 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine (5 μM) caused a significant rightward displacement of the vasoconstrictor effect of melatonin. In the case of 4-P-PDOT, the estimated pKB (6.17±0.16, n=8) is similar to the binding affinity for mt1 receptor.

Pre-incubation with 1 μM melatonin did not affect the conversion of [3H]-adenine to [3H]-cyclic AMP under basal condition (0.95±0.19% conversion (control) vs 0.92±0.19%, n=4) or following exposure to 30 μM forskolin (5.20±1.30% conversion (control) vs 5.35±0.90%, n=4).

Based on the above findings, we conclude that melatonin receptor on the tail artery belongs to the MT1 receptor subtype, and that this receptor is probably independent of the adenylyl cyclase pathway.

Keywords: Melatonin, MT2 selective antagonists, 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine, 4-P-PDOT, mt1 receptor subtype, MT2 receptor subtype, vasoconstriction, rat tail artery, RT–PCR, cyclic AMP

Introduction

The pineal hormone melatonin exerts numerous effects on the body, influencing circadian rhythms, the immune system and the cardiovascular system, for example. The majority of these actions are thought to be mediated through specific binding sites identified by [125I]-2-iodomelatonin, originally termed ML1 and ML2 receptor subtypes, that possess pharmacologically different characteristics based on the potency of both indole-based and non indolebased compounds (see Morgan et al., 1994). More recently, Reppert and coworkers (1994; 1995a) have cloned and characterized two high affinity, G-protein coupled receptors for melatonin from mammalian tissues that appear to belong to the ML1 subgroup. Both receptors also have the potential to couple negatively to adenylyl cyclase. The two cloned receptors, originally termed as Mel1a and Mel1b (Reppert et al., 1994; 1995a,1995b), have since been renamed mt1 and MT2, respectively (Dubocovich et al., 1998; The nomenclature and classification of melatonin receptors used here has been approved by the Nomenclature Committee of IUPHAR). The abbreviation ‘mt1' corresponds to the recombinant melatonin receptor subtype previously known as Mel1a, which has not yet been linked to a specific functional response. ‘MT2' refers to native receptors, previously known as Mel1b, which have been defined function and pharmacological characteristics similar to the recombinant ‘mt2'.

In the study of melatonin receptor pharmacology, two of the few functional bioassays available include the inhibition of Ca2+-dependent, electrical field-stimulated [3H]-dopamine release from the rabbit retina (Dubocovich 1983; 1985; 1988) and enhancement of electrically-evoked contractions in rat isolated tail artery (Krause et al., 1995; Ting et al., 1997). In the latter study, which involved the use of several indole-based and naphthalenic derivatives, we concluded that the receptor involved in the action of melatonin belonged to a Mel1-like (now comprising mt1 and MT2) receptor.

Recently, Dubocovich and coworkers (1997) compared the pharmacological profile of the melatonin receptor of rabbit retina to that of the recombinant mt1 and MT2 melatonin receptors. Their results show that the pharmacological profile of the recombinant MT2 melatonin receptor is similar to that of the functional melatonin receptor in the rabbit retina (Dubocovich et al., 1997). In addition, the reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) has also shown that MT2 mRNA is expressed in the retina (Reppert et al., 1995a). Unambiguous evidence for the presence of a functional correlate of the retinal MT2 receptor was provided by the finding of a series of amidotetraline derivatives (including 4-phenyl-2-acetamidotetraline, 4-P-ADOT) that behaved as potent antagonists against melatonin-induced inhibition of [3H]-dopamine release from the rabbit retina. In the case of the rat tail artery preparation, Bucher and colleagues (1999) have recently reported that luzindole, a putative MT2 selective antagonist, failed to affect melatonin-induced enhancement of phenylephrine-induced contractions. Based on exclusion criteria, and accompanying molecular biological data, the authors argued for the presence of Mela (MT1) receptors. On the other hand, Doolen et al. (1998) reported that 4-P-ADOT (3 μM) failed to affect melatonin-induced enhancement of phenylephrine-induced contractions at low melatonin concentrations (0.1–100 nM) but augmented the vasoconstrictor effect of high concentrations of melatonin (1–10 μM). Based on the effect of this antagonist, the authors proposed that both mt1 and MT2 receptors were present on the tail artery, and that the response to melatonin represented the net effect of a constrictor action on mt1 receptors and a relaxatory response via a MT2 receptor (Doolen et al., 1998).

In the present study, we have attempted to clarify the characteristics of melatonin receptor(s) on the rat tail artery. This has involved the use of RT–PCR to identify mt1 and MT2 receptor subtype mRNA expression, and measurement of cyclic AMP accumulation using the prelabelling [3H]-adenine technique described by Wright et al. (1995). In addition, we have examined pharmacologically the contributions of both receptors to the functional response to melatonin. Presently, there are no selective mt1 receptor ligands. We have, therefore, compared the effects of MT2 selective antagonists 4-phenyl-2-propionamidotetraline (4-P-PDOT), a congener of 4-P-ADOT (Dubocovich et al., 1997) and 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine, a newly synthesized derivative of luzindole (Teh & Sugden, 1998), against melatonin-induced enhancement of electrically-evoked responses.

Methods

Tissue preparation

Male juvenile (3–4 week old; 55–100 g) Wistar rats (strain BKW, from colony maintained at Biomedical Services Unit, Nottingham, U.K.) were housed in a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 08 00 h; lights off at 20 00 h). Rats were usually killed 1–2 h after lights on by decapitation. The ventral artery of the tail was dissected and placed onto a dissecting disc immersed in gassed modified Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) solution. Ring segments were removed and used for the comparative functional and biochemical studies. For RT–PCR, adjacent ring segment of some arteries were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C. The blood vessel was carefully cleaned of fat and connective tissues with the aid of a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ-2B, Japan), and divided into ring segments of 2–3 mm in length.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) experiments

Each tail artery ring segment sample was sonicated on ice in lysis buffer (Tris HCl 100 mM, pH 8.0, LiCl 500 mM, EDTA 10 mM, lithium dodecylsulphate 0.1%, dithiothreitol 5 mM) and mRNA was isolated using magnetic oligo (dT)25 beads (Dynal, Wirral, U.K.). cDNA was synthesized from each mRNA sample immediately. Oligo(dT)15 (250 ng) and random hexamers (750 ng) were added to the mRNA and the mixture heated (70°C, 5 min) to remove secondary RNA structure then cooled immediately on ice. DTT (20 mM), dATP, dCTP, dTTP and dGTP (all 0.5 mM, Promega, Southampton, U.K.), recombinant ribonuclease inhibitor (40 u, RNasin, Promega), avian myoblastosis virus-reverse transcriptase (10 u, AMV-RT, Promega) and diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water were added to make the final volume 20 μl and the mixture was incubated at 42°C for 1 h. AMV-RT was inactivated by heating at 98°C for 3 min. mRNA was also isolated from rat retina, liver, suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus and brain, and cDNA synthesized as described for tail artery.

Tail artery cDNA from seven individual rats and a cDNA pool (made up of equal amounts from each animal) was amplified by PCR using forward and reverse primers designed from the partial sequences of rat mt1 and MT2 receptors (Reppert et al., 1995a). For the mt1 receptor: sense primer 5′-GTG CTA CGT GTT CCT GAT ATG G-3′ bp 57–78; antisense primer 5′-GGA TCT GAG GCC ACA ATA AGA C-3′ bp 395–416. The predicted size of the mt1 PCR product was 360 bp. The mt1 primers were a kind gift from Dr J. Vanecek (Institute of Physiology, Prague, Czech Republic). For the MT2 receptor subtype two primer sets were designed with the aid of the PRIME programme on the Genetics Computer Group Sequence Analysis Software Package (Devereux et al., 1984) and synthesized (Life Technologies, Paisley, U.K.): sense primer (1bF) 5′-ATC TGT CAC AGT GCG ACC TAC C-3′ bp 10–31, antisense primer (1bR) 5′-TTC TCT CAG CCT TTG CCT TC-3′ bp 282–301; and sense primer (2bF) 5′-AGC CTC ATC TGG CTT CTC AC-5′ bp 70–89, antisense primer (2bR) 5′-TTG GAA GGA GGA AGT GGA TG-3′ bp 204–223. For the MT2 primer pair 1bF/1bR the predicted size of the PCR product was 292 bp, and for the 2bF/2bR primer pair the product was 154 bp. cDNA (1 μl from the 20 μl cDNA reaction volume) was amplified in a thermal cycler (Hybaid Omnigene) in a reaction (20 μl) containing 100 μM of each deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphate, 0.5 μM of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 u of Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Crawley, Sussex). A ‘hot-start' procedure was employed (D'Aquila et al., 1991) and thermal cycling conditions were 94°C, 1 min, 55°C, 1 min and 72°C, 2 min for 40 cycles with a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. PCR reaction products were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5–2.2% w v−1) and stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μ g ml−1).

To determine the identity of the amplification products agarose gel bands were excised and the DNA purified using a Qiaquick gel extraction kit (Quiagen). Purified mt1 PCR product was digested with the restriction enzyme BamHI (10 u, 37°C, overnight; Promega) or directly sequenced on an ABI automated sequencer (Department of Molecular Medicine, King's College Hospital, London). For MT2, 1 μl of the PCR mixture obtained using primers 1bF/1bR was subjected to a second round of PCR (20–40 cycles) with the nested MT2 primers 2bF/2bR.

Functional studies

Ring segments from the tail artery were suspended between two supporting jaws in a stainless steel chamber of a Mulvany-Halpern wire-myograph and allowed to equilibrate for 30 min (Ting et al., 1997). The initial resting tension was 0.2–0.3 g and preparations were allowed to relax to 0.1–0.2 g. Changes in isometric tension were recorded by a MacLab and displayed on a Macintosh computer. Vessels were contracted with KCl (60 mM) to assess tissue viability and provide a reference contraction for subsequent data analysis. The preparations were stimulated with a 5 s train of electrical pulses (10–20 V; 0.3 ms pulse width) at a frequency of 2–3 Hz every 4–5 min (Ting et al., 1997) with a D330-Multisystem stimulator (Digitimer, U.K.). The voltage and frequency of the electrical field stimulation were modified in the beginning of each set of experiments to obtain a contraction which was 20–35% of the response to 60 mM KCl. Upon obtaining constant, ‘baseline' neurogenic responses, non-cumulative concentration-response curves (CRC) were constructed for melatonin (0.01 nM–1 μM) as previously described (Ting et al., 1997). Antagonists were added at least 20 min before the construction of non-cumulative CRC of melatonin, and readded after the final washout between non-cumulative application of melatonin (20 min before the next addition of the agonist). The intrinsic activity of the antagonists per se was also examined. In an additional series of experiments, some of the vessels were stimulated with phenylephrine (50–100 nM) to produce a response approximately 25% of the response to 60 mM KCl. Upon establishing a stable contraction, 100 nM of melatonin was added in the absence and presence of the antagonist 4-P-PDOT (10 nM).

Second messenger studies

Ring segments (5 mm) of the tail artery were incubated for 60 min at 37°C in a shaking waterbath before incubation with [3H]-adenine (specific activity=851 GBq mmol−1, 74 kBq ml−1) for a further 60 min (Wright et al., 1995). Each segment was then transferred to a flat bottom vial containing K-H solution with a final assay volume of 300 μl and allowed to equilibrate for 20 min. Where appropriate, melatonin (1 μM) was added 10 min prior exposure to forskolin (30 μM). The reaction was terminated 5 min later by the addition of 200 μl 1 M HCl and followed by 750 μl of distilled water. [3H]-cyclic AMP was separated from [3H]-adenine and other [3H]-products using sequential Dowex/alumina chromatography (Salomon et al., 1974). In order to correct the results for variation in recovery, [14C]-cyclic AMP (c. 30 Bq) was added to each tube (Wright et al., 1995). [3H]-cyclic AMP levels were corrected for the recovery from the dowex/alumina chromatography by measurement of the total tritium taken up into tissue samples. [14C]-cyclic AMP, [3H]-cyclic AMP and total tritium in each sample were determined by liquid scintillation counting. All treatments were carried out in quadruplicate.

Data analysis

For studies involving isometric tension, responses have been expressed as percentage of the enhancement to the predrug, neurogenic or phenylephrine-induced contractions. The effect of the antagonist per se has been expressed as the percentage of basal (predrug) neurogenic responses. The sensitivity of the preparations to melatonin was assessed as the negative logarithm of the concentration required to produce 50% of the maximum response (pEC50) after the melatonin concentration-effect (E/[A]) data were fitted to the formula:

where E is the response, α is the asymptote, [A] is the agonist concentration, n is the gradient of the E/[A] curve and [A50] is the mid-point of E/[A] curve (Black et al., 1985). [A50] values represent melatonin concentration giving 50% of the maximum responses and are shown as the negative logarithm (pEC50). The maximum response (Emax) to melatonin in the absence and presence of the antagonist was compared. The negative logarithm of the dissociation constant for the antagonist (pKB value) was determined by the method of Furchgott (1972). For these experiments, the agonist concentration-ratio (CR) was determined in each preparation. The CR is the ratio of EC50 values of melatonin in the presence and absence of antagonist. For the biochemical studies, [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation has been expressed as a percentage of conversion of [3H]-adenine to [3H]-cyclic AMP.

Statistical analysis was performed using either two-way analysis of variance, paired or unpaired Student's t-test (two-tailed), as appropriate. Differences between mean values were considered statistically significant if P<0.05.

Solutions and drugs

The composition of the K-H solution was (in mM): NaCl 118.4, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 1.25, MgSO4 1.2, NaHCO3 24.9, KH2PO4 1.2 and glucose 11.1. The following compounds were used: L-phenylephrine HCl, melatonin, forskolin (Sigma); KCl (Fisons); 4-P-PDOT (4-phenyl-2-propionamidotetraline; Tocris); 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine (supplied by Dr Duncan Crawford, Tocris) and [3H]-adenine, [14C]-cyclic AMP (Amersham International, Amersham). 4-P-PDOT and melatonin were prepared as 10 mM stock solutions in 100% dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and DH97 was dissolved in 100% ethanol at 10 mM. Further dilutions were freshly prepared each day with distilled water except 4-P-PDOT (1 mM) in 50% DMSO. The maximum concentration of the solvent in the organ bath never exceeded 0.1% v v−1.

Results

Molecular characterization of melatonin receptor subtypes: RT–PCR

mt1 receptor subtype

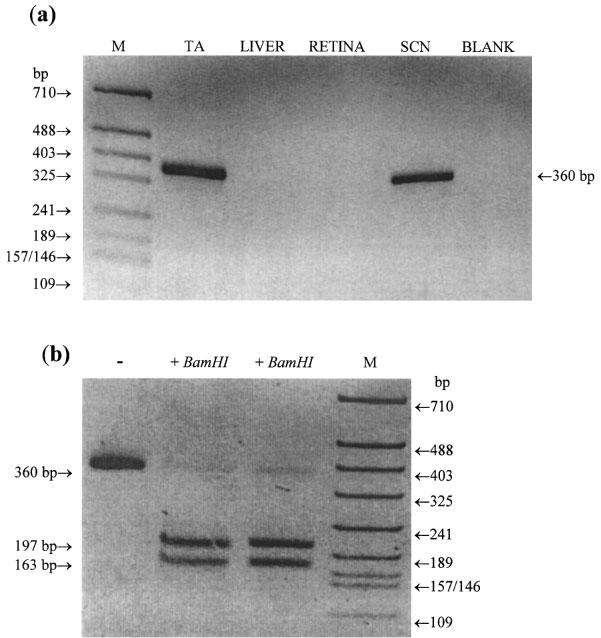

A single PCR product of the expected size (360 bp) was detected on amplification of cDNA prepared from all seven rat tail artery segments (Figure 1a). This product was also apparent when SCN cDNA was amplified but was not detected in liver or retina. Digestion of the purified mt1 PCR product with the restriction enzyme BamHI gave two bands of the size predicted (197 and 163 bp) from the published sequence of a rat mt1 receptor fragment (GenBank accession number U14409) (Figure 1b). Digestion of the SCN mt1 PCR product with BamHI also gave two fragments of this size (data not shown). Sequence analysis of the mt1 PCR product in the sense and antisense directions showed it to be 99.3% identical to the genuine mt1 sequence.

Figure 1.

(a) PCR of the mt1 receptor in rat tail artery (TA), liver, retina and suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). cDNA was amplified for 40 cycles using the specific mt1 receptor subtype primers and the conditions given in the Methods section. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5% w v−1) and stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg ml−1). A single product of the size expected (360 bp) was observed on amplification of tail artery and SCN cDNA but not with liver or retinal cDNA. Blank, no cDNA was included in the PCR amplification. M=molecular weight markers (HpaII digest of pBluescript SK+). (b) The PCR product of 360 bp amplified from tail artery was excised from the gel, purified and duplicate samples were digested with the restriction enzyme BamHI (10 u, 37°C, overnight). The products were separated on a 2.2% w v−1 agarose gel. Two fragments of the size expected for the genuine mt1 PCR product were obtained (197 and 163 bp).–, uncut mt1 PCR product.

MT2 receptor subtype

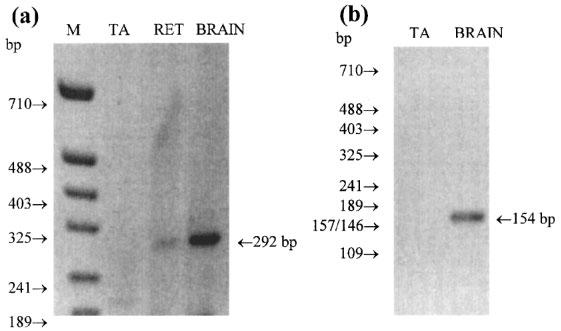

Amplification of the tail artery cDNA with MT2 specific primers (1bF/1bR) failed to generate any detectable PCR products (Figure 2a). Brain cDNA did yield a product of the expected size (292 bp), and a faint band was also seen in retina. To confirm the identity of the PCR product obtained with brain cDNA and to determine if a small amount of the product (below the limit of detection by ethidium bromide staining) had been produced for tail artery, nested PCR was done on a sample (1 μl) of the first round PCR mix. The primers used (2bF/2bR) anneal to sequences specific for the MT2 receptor contained within the 292 bp fragment. Nested PCR of the brain sample gave a single product of the expected size (154 bp) confirming that it was amplified from genuine MT2 receptor (Figure 2b). This product at 154 bp was evident for the brain sample after 20 PCR cycles (data not shown), but was not detected even after 40 cycles with the tail artery sample.

Figure 2.

(a) PCR of the MT2 receptor in tail artery (TA), retina (RET) and brain. cDNA was amplified for 40 cycles under the conditions given in the methods section using the specific MT2 receptor primers 1bF and 1bR. A single product of the size expected (292 bp) was observed on amplification of retina and brain cDNA but not with tail artery cDNA. M=molecular weight markers. (b) 1 μl of the 20 μl PCR reaction mixture from the tail artery and brain in (a) was re-amplified for a further 40 cycles using the nested primers 2bF and 2bR. Eight μl of the reaction mixture was separated on a 2.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. No amplification product was seen for the tail artery sample but a single product of the expected size (154 bp) was observed for the brain sample. This product was readily detected also after 20 cycles.

In a parallel series of experiments, adjacent ring segments of the tail artery from the same animals (n=7) used in the above study, responded to melatonin (0.1 nM–0.3 μM) with a concentration-dependent enhancement of electrically-evoked contractions (data not shown).

Pharmacological characterization of melatonin receptor subtypes

The binding affinities (pKi) of 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine to compete for [125I]-2-iodomelatonin binding to human recombinant mt1 and MT2 melatonin receptors expressed in NIH3T3 cells are 6.1 and 8.0, respectively (Teh & Sugden, 1998). The pKi values of 4-P-PDOT for mt1 and MT2 receptors are 6.3 and 8.8, respectively (Dubocovich et al., 1997). 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine and 4-P-PDOT exhibited 80–300 fold greater affinity for the MT2 binding site compared to mt1 binding sites. On the basis of these data, 60 nM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine and 10 and 100 nM 4-P-PDOT were used as selective concentrations to examine the effect of MT2 binding sites, while 5 μM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine and 3 μM 4-P-PDOT were employed to affect both MT2 and mt1 binding sites. Neither the high nor the low concentrations of the antagonists affected the basal tone of the isolated tail artery.

Electrical field stimulation of the rat tail artery every 4–5 min caused a reproducible, transient contraction equivalent to 25.1±3.0% of the response to 60 mM KCl (0.93±0.10 g, n=11). MT2 selective concentrations of the ligands failed to affect the electrically-evoked responses (n=4). However, 5 μM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine significantly suppressed electrically-evoked responses (64.6±7.9% of basal responses, n=4) while 3 μM 4-P-PDOT significantly increased the electrically-evoked responses (182.7±12.1% of basal responses, n=4).

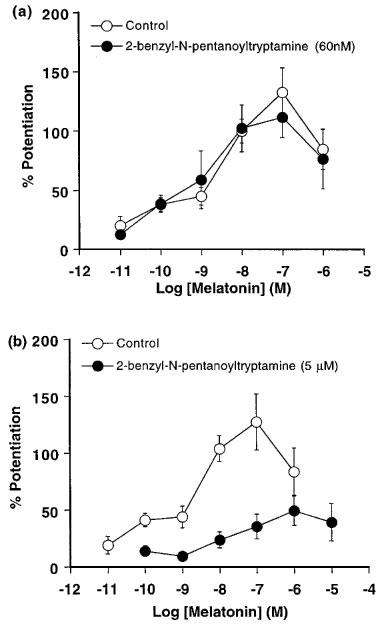

Effect of 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine against vascular responses to melatonin

As shown in Figure 3, melatonin (0.1 nM–1 μM) produced a concentration-dependent enhancement of the electrically-evoked contractions. Sixty nM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine failed to modify the effect of melatonin against electrically-evoked contractions (Figure 3a and Table 1). In contrast, 5 μM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine caused a non-parallel rightward displacement of the concentration-response curve for melatonin which was associated with a significant reduction in the maximum response (Figure 3b and Table 1). The latter effect prevented an accurate estimate of the mid point of the concentration-response curve in the presence of 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine and, therefore, determination of the pKB value.

Figure 3.

Effect of 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine (a) 60 nM (n=6) and (b) 5 μM (n=5) on the concentration-response curves for melatonin against electrically-evoked contractions (2–3 Hz, 0.3 ms pulse width, 10–20 V) of isolated tail arteries from juvenile rats. Responses have been expressed as the percentage enhancement of the electrically-evoked contractions (measured prior to exposure to melatonin) and are shown as the mean±s.e.mean (vertical lines).

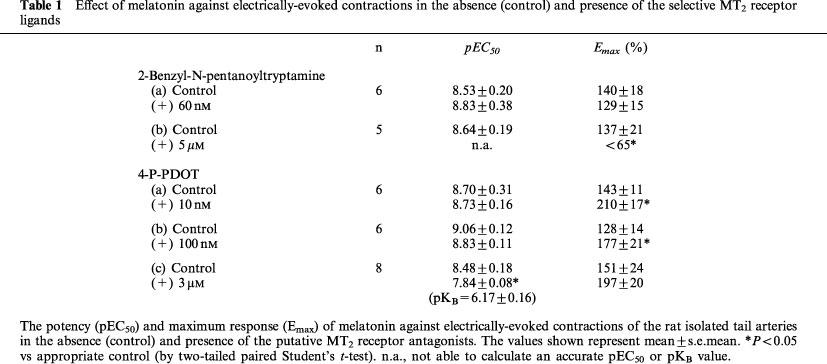

Table 1.

Effect of melatonin against electrically-evoked contractions in the absence (control) and presence of the selective MT2 receptor ligands

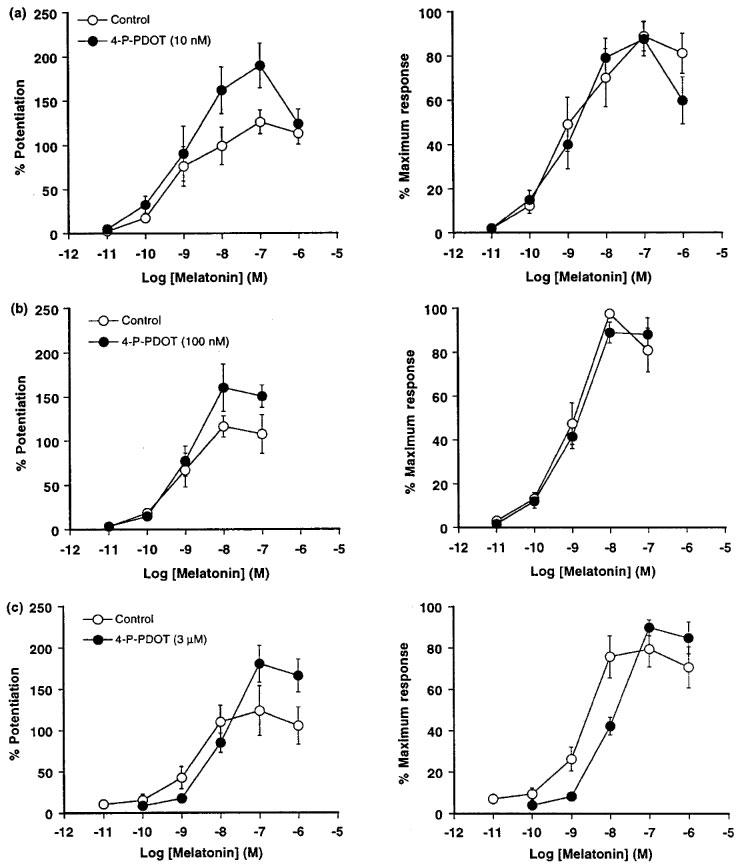

Effect of 4-P-PDOT against vascular responses to melatonin

The maximum response (Emax) to melatonin was increased further in the presence of 4-P-PDOT (10 nM–3 μM; Table 1). However, this enhancing effect of 4-P-PDOT (30–45% in all preparations) was largely independent of concentration (see Table 1). Therefore, the data obtained from this series of study were also expressed as a percentage of the maximum response observed in each preparation to enable easier, visual detection of any shift in melatonin response curves (see Figure 4, left and right).

Figure 4.

Effect of 4-P-PDOT (a) 10 nM (n=6), (b) 100 nM (n=6) and (c) 3 μM (n=8) on the concentration-response curves for melatonin against electrically-evoked contractions (2–3 Hz, 0.3 ms pulse width, 10–20 V) of isolated tail arteries from juvenile rats. For graphs on the left, responses have been expressed as the percentage enhancement of the electrically-evoked contractions (measured prior to exposure to melatonin) and are shown as the mean±s.e.mean (vertical lines). For graphs on the right, responses have been expressed as the percentage of the maximum response.

4-P-PDOT (10–100 nM) did not significantly alter the sensitivity of the preparations to melatonin (see Figure 4a and b). However, a non-selective concentration of 4-P-PDOT (3 μM) caused a significant 5 fold rightward shift of the concentration-response curve for melatonin (Figure 4c and Table 1) with an estimated pKB value of 6.17±0.16 (n=8).

In a separate study, phenylephrine (50–100 nM) produced stable, sustained contractions in the tail artery (24.5±3.4% of the 60 mM KCl response, n=8). Melatonin (100 nM) enhanced phenylephrine-induced contractions (208.2±29.2%, n=8) in the rat tail artery. In the presence of 4-P-PDOT (10 nM) the response to melatonin was not different compared to the control group (227.5±28.3%, n=8; P>0.05).

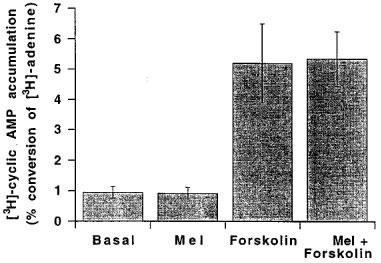

Melatonin and [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation

Under basal conditions, 0.95±0.19% (n=4) of [3H]-adenine was converted to [3H]-cyclic AMP by 5 mm segments of rat tail artery. Following exposure to 30 μM forskolin, the accumulation of [3H]-cyclic AMP increased 5 fold to 5.20±1.30% (n=4) of [3H]-adenine. As shown in Figure 5, 1 μM melatonin did not affect [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation under either basal condition (0.92±0.19%, n=4) or in the presence of 30 μM forskolin (5.35±0.90%, n=4).

Figure 5.

Effects of 1 μM melatonin (mel), 30 μM forskolin and a combination of melatonin and forskolin on [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation in the rat isolated tail artery. The results have been expressed as percentage conversion of [3H]-adenine to [3H]-cyclic AMP and are shown as the mean±s.e.mean of four separate experiments (each conducted in quadruplicate).

Discussion

In an earlier study of the melatonin receptor mediating enhancement of neurogenic contractions of the rat isolated tail artery (Ting et al., 1997), we concluded that the receptor belonged to the Mel1 subgroup (now comprising mt1 and MT2 receptors) but were unable to determine conclusively which subtype was implicated. In the present study, we have employed molecular biological techniques, to establish which receptor subtype mRNA may be expressed and pharmacological approaches to provide confirmation of a functional correlate. In the latter instance, however, it has been necessary to rely upon exclusion criteria for identifying the functional receptor; while there are agents available that possess 100 fold selectivity for the MT2 subtype, there are no corresponding tools for the mt1 receptor subtype. Nonetheless, our results suggest strongly that the rat tail artery expresses only one melatonin receptor subtype. Based on the Nomenclature-Committee of IUPHAR recommendations (Vanhoutte et al., 1998), the recombinant mt1 receptor has now been shown to be of a functional relevance (i.e. mediates the enhancement of electrically-evoked contractions in the rat tail artery) can now be referred as MT1 melatonin receptor.

Molecular biological evidence for mt1 receptor subtype

Using RT–PCR mt1 mRNA was detected in rat tail artery segments identical to those used in the functional experiments, and was also identified in SCN, but not in liver or retina. The transcript for the mt1 receptor has previously been found in the SCN of various rodents by in situ hybridization (Reppert et al., 1994; Roca et al., 1996), but it was not found in liver and was just detectable in retina by RT–PCR (Reppert et al., 1995a). Although the full coding sequence of the rat mt1 receptor has not yet been isolated, the fragment which has been sequenced (Reppert et al., 1995b) has a deduced amino acid sequence 89% identical to the human mt1 receptor. The PCR product amplified from tail artery cDNA was identified as a genuine mt1 product by restriction analysis and sequencing.

RT–PCR failed to detect MT2 mRNA in tail artery, but did identify MT2 transcripts in cDNA prepared from brain and retina after 40 cycles of PCR. Although there is an apparent low level of expression of MT2 receptor transcripts precluding detection by in situ hybridization (Reppert et al., 1995a), expression has been shown in brain and retina by RT–PCR. In our experiments, a second round of PCR using nested primers which anneal to specific MT2 sequences within the first round PCR product confirmed that the product generated from brain cDNA was genuine MT2 product, but did not amplify a specific MT2 fragment from tail artery. Thus, despite the very sensitive techniques employed we could find no evidence to support the contention that the MT2 receptor is expressed in rat tail artery. It is noteworthy that our findings are consistent with the preliminary RT–PCR results of Krause and coworkers (1996) that both rat and human cerebral arteries possess mt1 transcripts.

Pharmacological evidence for MT1 receptor in the rat tail artery

Several studies have shown that physiological levels of melatonin can increase vascular tone in perfused rat tail artery (Vandeputte et al., 1997) or isolated tail artery (Evans et al., 1992). Direct vasoconstriction to melatonin is observed when vessels are pressurized (Evans et al., 1992; Ting et al., 1997) but no direct constriction is apparent in tail artery maintained under isometric tension. However, melatonin is able to potentiate agonist-induced and electrically-evoked contractions in the rat isolated tail artery (Viswanathan et al., 1990; Krause et al., 1995). The binding sites for melatonin appeared to be restricted to the smooth muscle layer (Viswanathan et al., 1990; Seltzer et al., 1992). In this present study, we observed the effect of melatonin in both phenylephrine-induced and electrically-evoked, isometric contractions in the rat isolated tail artery, supporting the view that melatonin acts at a postjunctional site. This action appears to proceed through a cyclic AMP-independent pathway, possibly via closure of Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Geary et al., 1998), since melatonin failed to inhibit either basal or forskolin-elevated levels of [3H]-cyclic AMP accumulation. Although there are several reports which suggest that activation of melatonin receptors is associated with a reduction in forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP, it is significant that this has usually been observed in recombinant systems with a high level of receptor expression (Reppert et al., 1994; Browning et al., 1997). Interestingly, Conway and coworkers (1997) noted that while melatonin reduced cyclic AMP formation in cell line HEK293 stably expressing recombinant melatonin receptors (∼400 fmol mg−1), it failed to do so in HEK293 cells expressing low level of native melatonin receptors (∼1.1 fmol mg−1). Since the density of melatonin receptors on the tail ranges from 15–29 fmol mg−1 (Viswanathan et al., 1990; 1992), it appears unlikely that modulation of cyclic AMP formation contributes to the vasoconstrictor action of melatonin.

As indicated earlier, the lack of mt1 and MT2 receptors selective radioligands and analogues has hindered the characterization of melatonin receptor subtypes in native tissues (Dubocovich et al., 1997). Recently, however, Dubocovich and coworkers (1997) have demonstrated that human mt1 and MT2 recombinant melatonin receptors can be distinguished pharmacologically using a series of non indole-based melatonin antagonists, including the amidotetraline derivative 4-P-P-DOT, which display over 300 times higher affinity for the MT2 compared to the mt1 subtype (Dubocovich et al., 1997). Another recently characterized MT2 selective ligand, 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine, a derivative of the indole-based antagonist luzindole, also has high (90 fold) selectivity for the recombinant MT2 receptor expressed in NIH3T3 cells (Teh & Sugden, 1998).

Appropriate concentrations of the antagonists were chosen based on the affinity constant (pKi) of these agents for recombinant MT2 and mt1 receptors determined by radioligand binding. At low concentrations, neither 10 nM 4-P-PDOT nor 60 nM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine significantly altered the potency of melatonin in the rat tail artery. It is noteworthy, however, that 10 nM 4-P-PDOT, but not 60 nM 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine, significantly increased the maximum effect of melatonin against electrically-evoked contractions. This effect of 4-P-PDOT appears to be concentration-independent and, since it failed to enhance the action of melatonin against phenylephrine-induced contractions, involve a prejunctional site. A role for prejunctional MT2 receptor seems unlikely for two reasons. First, this action was not seen with 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine. Second, we failed to detect any molecular biological evidence to support the presence of the MT2 receptor (see above). While the effect of 4-P-PDOT is qualitatively similar that reported by Doolen and coworkers (1998) for the analogue 4-A-PDOT, which was the basis of their suggestion for the presence of MT2 receptors on the tail artery of Fischer 344 adult rats, it is significant that they did not employ concentrations of the agent with proven selectivity for the MT2 receptor subtype. Thus, we are unable to support claims that responses to melatonin in this preparation represent the sum of pharmacologically different receptors that mediate functionally opposing responses on vascular smooth muscle (see Doolen et al., 1998).

At higher, non-selective concentrations of the antagonists both agents inhibited the effect of melatonin against neurogenic responses of the rat isolated tail artery. Significantly, the amidotetraline derivative 4-P-PDOT (3 μM) produced a competitive antagonism of the effect of melatonin. The calculated pKB for 4-P-PDOT (6.1) was very similar to the binding affinity constant to the mt1 receptor subtype (pKi=6.3; Dubocovich et al., 1997) and, as such, provides the first functional correlate of a MT1 receptor; the recent study of Bucher and colleagues (1999) excluded a role for MT2 (Mel1b) receptors but failed to provide pharmacological evidence for the involvement of MT1 receptors. In addition, we have also observed a modest degree of a concentration-dependent enhancement against neurogenic contractions of 4-P-PDOT per se (data not shown) suggesting that 4-P-PDOT may act as a weak partial agonist at the vascular melatonin receptor. In the case of the indole-based analogue 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine (5 μM), the maximum response to melatonin was also significantly reduced which made it difficult to calculate an accurate pKB value. The basis of this effect is unclear, but it appears to be a consequence of an inhibitory action per se on the neurogenic response.

In conclusion, based on the molecular biological and pharmacological criteria adopted we have identified the melatonin receptor on the tail artery of the rat as belonging to the MT1 receptor subtype. As such, our findings represent the first functional correlate for the MT1 subtype which, unlike the studies of recombinant receptors on different cell lines, does not appear to be negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Duncan Crawford for supplying 2-benzyl-N-pentanoyltryptamine and Dr J. Vanecek for providing mt1 receptor primers.

Abbreviations

- CRC

concentration-response curve

- cyclic AMP

3′ : 5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- DMSO

dimethylsuphoxide

- K-H

Krebs-Henseleit

- 4-P-ADOT

4-Phenyl-2-acetamidotetraline

- 4-P-PDOT

4-phenyl-2-propionamidotetraline

- RET

retina

- RT–PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- TA

tail artery

References

- BLACK J.W., LEFF P., SHANKLEY N.P. An operational model of pharmacological agonism: the effect of E/[A] curve shape on agonist dissociation constant estimation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;84:561–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb12941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWNING C., BROWN J.D., BERESFORD I.J.M., GILES H. Pharmacological characterization of [3H]-melatonin binding to human recombinant mt1 and MT2 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:361P. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCHER B., GAUER F., PEVET P., MASSON-PEVET M. Vasoconstrictor effect of various melatonin analogs on the rat tail artery in the presence of phenylephrine. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1999;33:316–322. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199902000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONWAY S., DREW J.E., CANNING S.J., BARRETT P., JOCKERS R., STROSBERG A.D., GUARDIOLA-LEMAITRE B., DELAGRANGE P., MORGAN P.J. Identification of Mel1a melatonin receptors in the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293: evidence of G-protein-coupled melatonin receptors which do not mediate the inhibition of stimulated cyclic AMP levels. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'AQUILA R.T., BECHTEL L.J., VIDELER J.A., ERON J.J., GORCZYCA P., KAPLAN J.C. Maximizing sensitivity and specificity of PCR by preamplification heating. Neuron. 1991;13:1177–1185. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.13.3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVEREUX J., HAEBERLI P., SMITHIES A. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for VAX and CONVEX systems. Nuc. Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOOLEN S., KRAUSE D.N., DUBOCOVICH M.L., DUCKLES S.P. Melatonin mediates two distinct responses in vascular smooth muscle. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;345:67–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBOCOVICH M.L. Melatonin is a potent modulator of dopamine release in the retina. Nature. 1983;306:782–784. doi: 10.1038/306782a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBOCOVICH M.L. Characterization of a retinal melatonin receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985;234:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBOCOVICH M.L. Luzindole (N-0774): A novel melatonin receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;246:902–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBOCOVICH M.L., CARDINALI D.P., GUARDIOLA-LEMAITRE B., HAGAN R.M., SUGDEN D., VANHOUTTE P.M., YOCCA F.D. The IUPHAR Compendium of Receptor Characterization and Classification. IUPHAR Media, London; 1998. Melatonin receptors; pp. 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- DUBOCOVICH M.L., MASANA M.I., IACOB S., SAURI D.M. Melatonin receptor antagonists that differentiate between the human Mel(1a), and Mel(1b) recombinant subtypes are used to assess the pharmacological profile of the rabbit retina ML(1) presynaptic heteroreceptor. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1997;355:365–375. doi: 10.1007/pl00004956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS B.K., MASON R., WILSON V.G. Evidence for direct vasoconstriction activity of melatonin in ‘pressurized' segments of isolated caudal artery from juvenile rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1992;346:362–365. doi: 10.1007/BF00173553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURCHGOTT R.F.The classification of adrenoceptors (adrenergic receptors). An evaluation from the standpoint of receptor theory Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Catecholamines 1972Vol 33Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 283–335.eds. Blaschko, H. & Muscholl, E. pp [Google Scholar]

- GEARY G.G., DUCKLES S.P., KRAUSE D.N. Effect of melatonin in the rat tail artery: role of K+ channels and endothelial factors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1533–1540. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAUSE D.N., BARRIOS V.E., DUCKLES S.P. Melatonin receptors mediate potentiation of contractile responses to adrenergic nerve stimulation in rat caudal artery. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;276:207–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00028-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAUSE D.N., DUBOCOVICH M.L., EDVINSSON L., GEARY G.G., MASANA M.I., DUCKLES S.P. Mel1a melatonin receptors in human and rat cerebral peripheral arteries: mRNA expression and functional pharmacology. Soc. Neurosci. Abst. 1996;22:551–19. [Google Scholar]

- MORGAN P.J., BARRETT P., HOWELL H.E., HELLIWELL R. Melatonin receptors: Localization, molecular pharmacology and physiological significance (Invited review) Neurochem. Int. 1994;24:101–146. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REPPERT S.M., GODSON C., MAHLE C.D., WEAVER D.R., SLAUGENHAUPT S.A., GUSELLA J.F. Molecular characterisation of a second melatonin receptor expressed in human retina and brain: The Mel1b melatonin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995a;92:8734–8738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REPPERT S.M., WEAVER D.R., CASSONE V.M., GODSON C., KOLAKOWSKI L.F. Melatonin receptors are for the birds: molecular analysis of two receptor subtypes differentially expressed in chick brain. Neuron. 1995b;15:1003–1015. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REPPERT S.M., WEAVER D.R., EBISAWA T. Cloning and characterisation of a mammalian melatonin receptor that mediates reproductive and circadian responses. Neuron. 1994;13:1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCA A.L., GODSON C., WEAVER D.R., REPPERT S.M. Structure, characterization and expression of the gene encoding the mouse Mel1a melatonin receptor. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3469–3477. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.8.8754776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALOMON Y., LONDOS C., RODBELL M. A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal. Biochem. 1974;58:541–548. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELTZER A., VISWANATHAN M., SAAVEDRA J.M. Melatonin-binding sites in brain and caudal arteries of the female rat during the estrous cycle and after estrogen administration. Endocrinology. 1992;130:1896–1902. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.4.1547717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGDEN D., PICKERING H., TEH M-T., GARRATT P.J. Melatonin receptor pharmacology: towards subtype specificity. Biol. Cell. 1997;89:531–537. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(98)80009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEH M-T., SUGDEN D. Comparison of the structure-activity relationships of melatonin receptor agonists and antagonists: lengthening the N-acyl side chain has differing effect on potency on Xenopus melanophores. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1998;358:522–528. doi: 10.1007/pl00005288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TING K.N., DUNN W.R., DAVIES D.J., SUGDEN D., DELAGRANGE P., GUARDIOLA-LEMAITRE B., SCALBERT E., WILSON V.G. Studies on the vasoconstrictor action of melatonin and putative melatonin receptor ligands in the tail artery of juvenile Wistar rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1299–1306. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANDEPUTTE C., DELAGRANGE P., SCALBERT E., TRAN N.P.N., ATKINSON J., CAPDEVILLE-ATKINSON C. Melatonin potentiates the contractile response to noradrenaline without modifying intracellular calcium mobilisation in the rat perfused tail artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:383P. [Google Scholar]

- VANHOUTTE P.M., HUMPHREY P.P.A., SPEDDING M. The IUPHAR Compendium of Receptor Characterization and Classification. IUPHAR Media, London; 1998. NC-IUPHAR recommendations for nomenclature of receptor; pp. 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- VISWANATHAN M., LAITINEN J.T., SAAVEDRA J.M. Expression of melatonin receptors in arteries involved in thermoregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:6200–6203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VISWANATHAN M., LAITINEN J.T., SAAVEDRA J.M. Differential expression of melatonin receptors in spontaneouly hypertensive rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;56:864–870. doi: 10.1159/000126318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT I.K., HARLING R., KENDALL D.A., WILSON V.G. Examination of the role of inhibition of cyclic AMP in α2-adrenoceptor mediated contractions of the porcine isolated palmar lateral vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:157–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14920.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]