Abstract

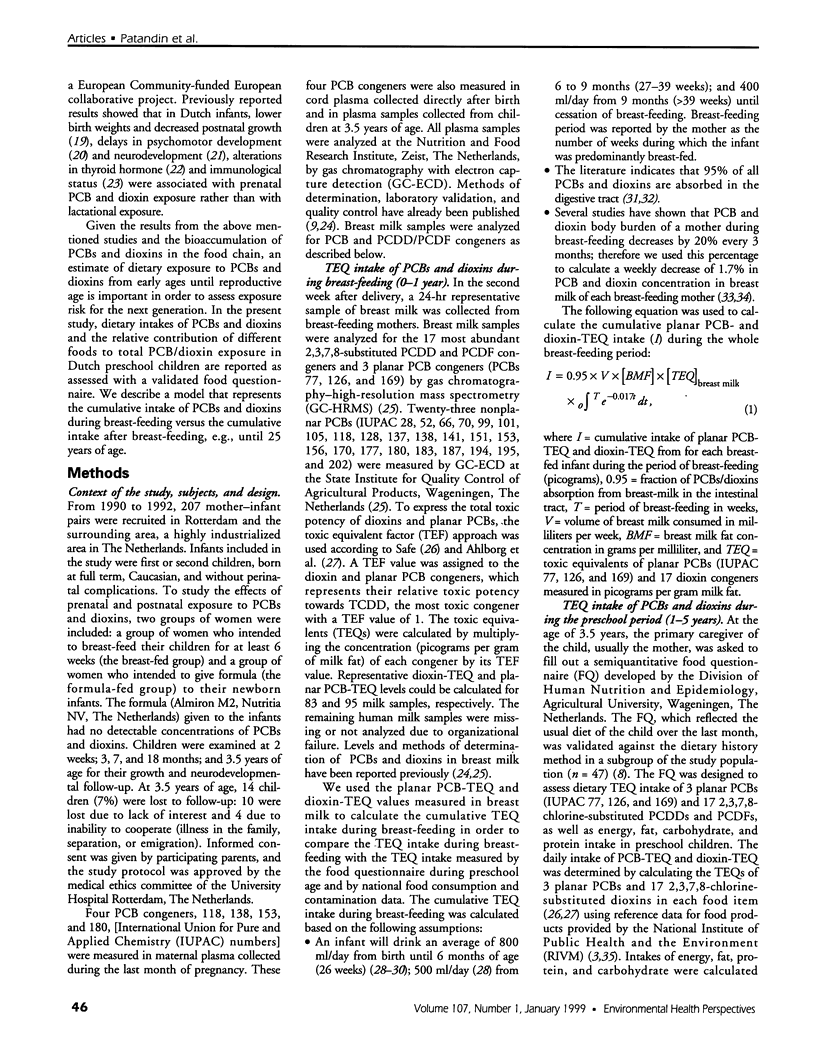

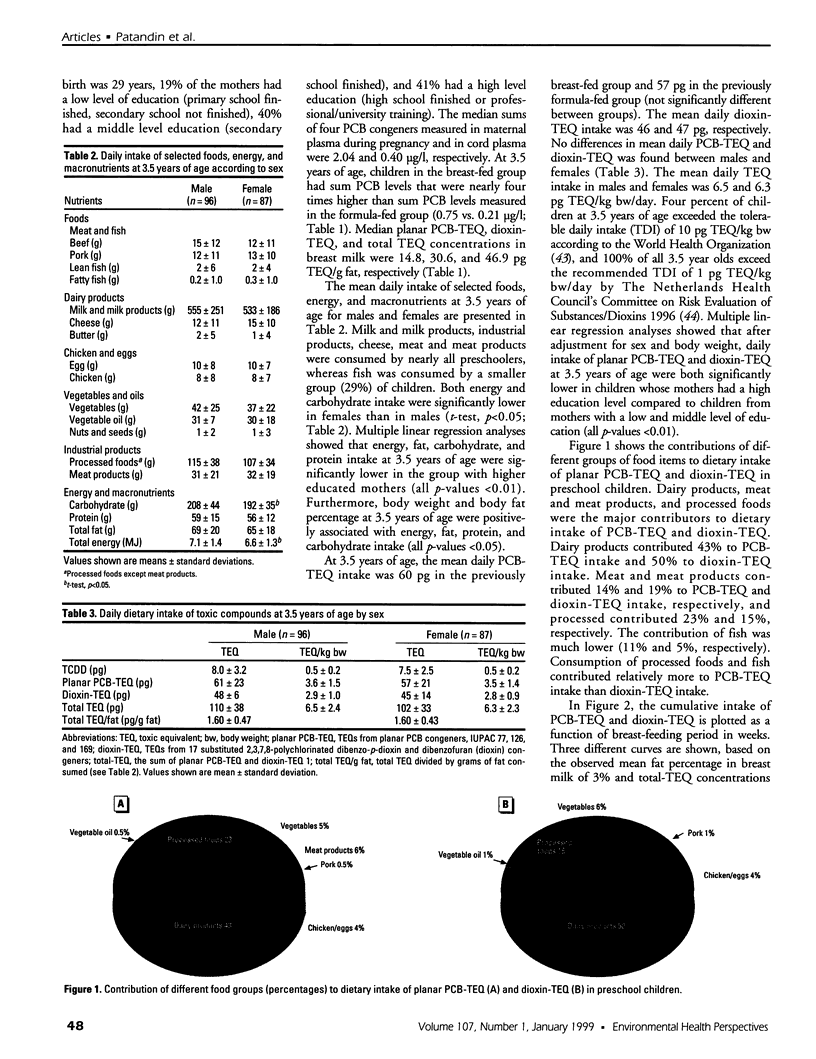

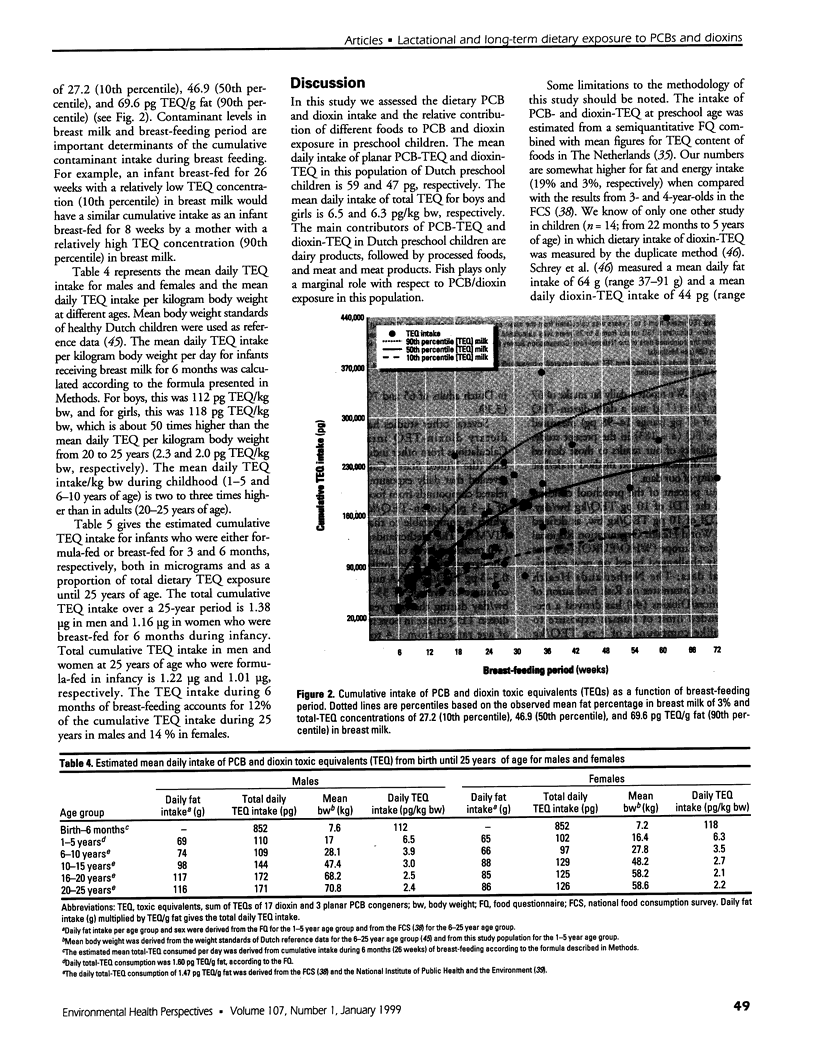

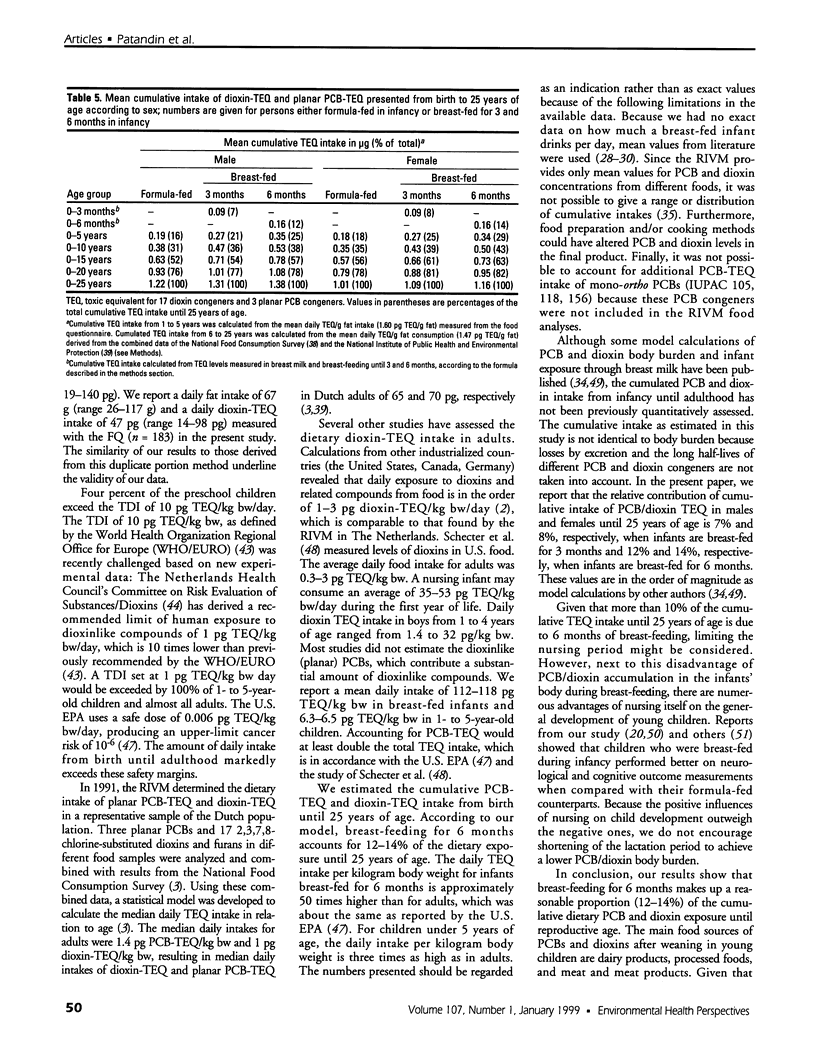

Food is the major source for polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) and dioxin accumulation in the human body. Therefore, investigating food habits from early ages until reproductive age (25 years) is important in order to assess exposure risk for the next generation. The objective of this study was to assess the PCB/dioxin exposure and the relative contribution of different foods to total exposure during preschool age. Particularly, the importance of lactational PCB/dioxin exposure vs. dietary exposure until adulthood was investigated. A cohort of 207 children was studied from birth until preschool age. Based on 3 planar PCBs and 17 2,3,7,8-substituted dibenzo-para-dioxins (PCDDs) and dibenzofurans (PCDFs) measured in breast milk, a model was developed to calculate the cumulative toxic equivalent (TEQ) intake during breast-feeding (0-1 year). In 3. 5-year-old children, daily dietary intake of planar PCB-TEQ and dioxin-TEQ was measured with a validated food questionnaire. Cumulative TEQ intake from 1 to 5 years was estimated using the PCB- and dioxin-TEQ intake measured with the food questionnaire. Cumulative TEQ intake from 6 to 25 years was estimated using national food consumption and contamination data of PCB- and dioxin-TEQ intake. In toddlers, dairy products contributed 43% to PCB-TEQ and 50% to dioxin-TEQ intake. Meat and meat products contributed 14% and 19%, respectively, and processed foods 23% and 15%, respectively. Breast-feeding for 6 months contributed to the cumulative PCB/dioxin TEQ intake until 25 years of age, 12% in boys and 14% in girls. The daily TEQ intake per kilogram body weight is 50 times higher in breast-fed infants and three times higher in toddlers than in adults. Long-term dietary exposure to PCBs and dioxins in men and women is partly due to breast-feeding (12 and 14%, respectively). After weaning, dairy products, processed foods, and meat are major contributors of PCB and dioxin accumulation until reproductive age. Instead of discouraging breast-feeding, maternal transfer of PCBs and dioxins to the next generation must be avoided by enforcement of strict regulations for PCB and dioxin discharge and by reducing consumption of animal products and processed foods in all ages.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abraham K., Knoll A., Ende M., Päpke O., Helge H. Intake, fecal excretion, and body burden of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in breast-fed and formula-fed infants. Pediatr Res. 1996 Nov;40(5):671–679. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers J. M., Kreis I. A., Liem A. K., van Zoonen P. Factors that influence the level of contamination of human milk with poly-chlorinated organic compounds. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1996 Feb;30(2):285–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00215810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck H., Dross A., Mathar W. PCDD and PCDF exposure and levels in humans in Germany. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Jan;102 (Suppl 1):173–185. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butte N. F., Garza C., Stuff J. E., Smith E. O., Nichols B. L. Effect of maternal diet and body composition on lactational performance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984 Feb;39(2):296–306. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl P., Lindström G., Wiberg K., Rappe C. Absorption of polychlorinated biphenyls, dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans by breast-fed infants. Chemosphere. 1995 Jun;30(12):2297–2306. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)00102-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey K. G., Heinig M. J., Nommsen L. A., Lonnerdal B. Maternal versus infant factors related to breast milk intake and residual milk volume: the DARLING study. Pediatrics. 1991 Jun;87(6):829–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte-Davidson R., Jones K. C. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the UK population: estimated intake, exposure and body burden. Sci Total Environ. 1994 Jul 11;151(2):131–152. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G. G., Jacobson J. L., Jacobson S. W., Schwartz P. M., Dowler J. K. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls: effects on birth size and gestational age. J Pediatr. 1984 Aug;105(2):315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch-Janys D., Becher H., Gurn P., Jung D., Konietzko J., Manz A., Päpke O. Elimination of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in occupationally exposed persons. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1996 Mar;47(4):363–378. doi: 10.1080/009841096161708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon N. Nutrition and cognitive function. Brain Dev. 1997 Apr;19(3):165–170. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(96)00560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M., Eerenstein S. E., Koopman-Esseboom C., Brouwer M., Fidler V., Muskiet F. A., Sauer P. J., Boersma E. R. Perinatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins through dietary intake. Chemosphere. 1995 Nov;31(10):4273–4287. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)00296-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M., Koopman-Esseboom C., Fidler V., Hadders-Algra M., van der Paauw C. G., Tuinstra L. G., Weisglas-Kuperus N., Sauer P. J., Touwen B. C., Boersma E. R. Perinatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins and its effect on neonatal neurological development. Early Hum Dev. 1995 Apr 14;41(2):111–127. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(94)01611-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J. L., Fein G. G., Jacobson S. W., Schwartz P. M., Dowler J. K. The transfer of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs) across the human placenta and into maternal milk. Am J Public Health. 1984 Apr;74(4):378–379. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.4.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J. L., Jacobson S. W. Intellectual impairment in children exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls in utero. N Engl J Med. 1996 Sep 12;335(11):783–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609123351104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman-Esseboom C., Morse D. C., Weisglas-Kuperus N., Lutkeschipholt I. J., Van der Paauw C. G., Tuinstra L. G., Brouwer A., Sauer P. J. Effects of dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls on thyroid hormone status of pregnant women and their infants. Pediatr Res. 1994 Oct;36(4):468–473. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman-Esseboom C., Weisglas-Kuperus N., de Ridder M. A., Van der Paauw C. G., Tuinstra L. G., Sauer P. J. Effects of polychlorinated biphenyl/dioxin exposure and feeding type on infants' mental and psychomotor development. Pediatrics. 1996 May;97(5):700–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda Y., Kagawa R., Kuroki H., Kuratsune M., Yoshimura T., Taki I., Kusuda M., Yamashita F., Hayashi M. Transfer of polychlorinated biphenyls from mothers to foetuses and infants. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1978 Dec;16(6):543–546. doi: 10.1016/s0015-6264(78)80221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patandin S., Koopman-Esseboom C., de Ridder M. A., Weisglas-Kuperus N., Sauer P. J. Effects of environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins on birth size and growth in Dutch children. Pediatr Res. 1998 Oct;44(4):538–545. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199810000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patandin S., Weisglas-Kuperus N., de Ridder M. A., Koopman-Esseboom C., van Staveren W. A., van der Paauw C. G., Sauer P. J. Plasma polychlorinated biphenyl levels in Dutch preschool children either breast-fed or formula-fed during infancy. Am J Public Health. 1997 Oct;87(10):1711–1714. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluim H. J., Boersma E. R., Kramer I., Olie K., van der Slikke J. W., Koppe J. G. Influence of short-term dietary measures on dioxin concentrations in human milk. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Nov;102(11):968–971. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan W. J., Gladen B. C., Hung K. L., Koong S. L., Shih L. Y., Taylor J. S., Wu Y. C., Yang D., Ragan N. B., Hsu C. C. Congenital poisoning by polychlorinated biphenyls and their contaminants in Taiwan. Science. 1988 Jul 15;241(4863):334–336. doi: 10.1126/science.3133768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S. H. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): environmental impact, biochemical and toxic responses, and implications for risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1994;24(2):87–149. doi: 10.3109/10408449409049308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A., Startin J., Wright C., Kelly M., Päpke O., Lis A., Ball M., Olson J. R. Congener-specific levels of dioxins and dibenzofurans in U.S. food and estimated daily dioxin toxic equivalent intake. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Nov;102(11):962–966. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner J. M., Whitehouse R. H. Revised standards for triceps and subscapular skinfolds in British children. Arch Dis Child. 1975 Feb;50(2):142–145. doi: 10.1136/adc.50.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilson H. A., Jacobson J. L., Rogan W. J. Polychlorinated biphenyls and the developing nervous system: cross-species comparisons. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1990 May-Jun;12(3):239–248. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(90)90095-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuinstra L. G., Traag W. A., van Rhijn J. A., vd Spreng P. F. The Dutch PCB/Dioxin Study. Development of a method for the determination of dioxins, planar and other PCBs in human milk. Chemosphere. 1994 Nov-Dec;29(9-11):1859–1875. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisglas-Kuperus N., Sas T. C., Koopman-Esseboom C., van der Zwan C. W., De Ridder M. A., Beishuizen A., Hooijkaas H., Sauer P. J. Immunologic effects of background prenatal and postnatal exposure to dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls in Dutch infants. Pediatr Res. 1995 Sep;38(3):404–410. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199509000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weststrate J. A., Deurenberg P. Body composition in children: proposal for a method for calculating body fat percentage from total body density or skinfold-thickness measurements. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989 Nov;50(5):1104–1115. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.5.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M. S., Fischbein A., Selikoff I. J. Changes in PCB serum concentrations among capacitor manufacturing workers. Environ Res. 1992 Oct;59(1):202–216. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(05)80240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakushiji T., Watanabe I., Kuwabara K., Tanaka R., Kashimoto T., Kunita N., Hara I. Postnatal transfer of PCBs from exposed mothers to their babies: influence of breast-feeding. Arch Environ Health. 1984 Sep-Oct;39(5):368–375. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1984.10545866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita F., Hayashi M. Fetal PCB syndrome: clinical features, intrauterine growth retardation and possible alteration in calcium metabolism. Environ Health Perspect. 1985 Feb;59:41–45. doi: 10.1289/ehp.59-1568075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]