Abstract

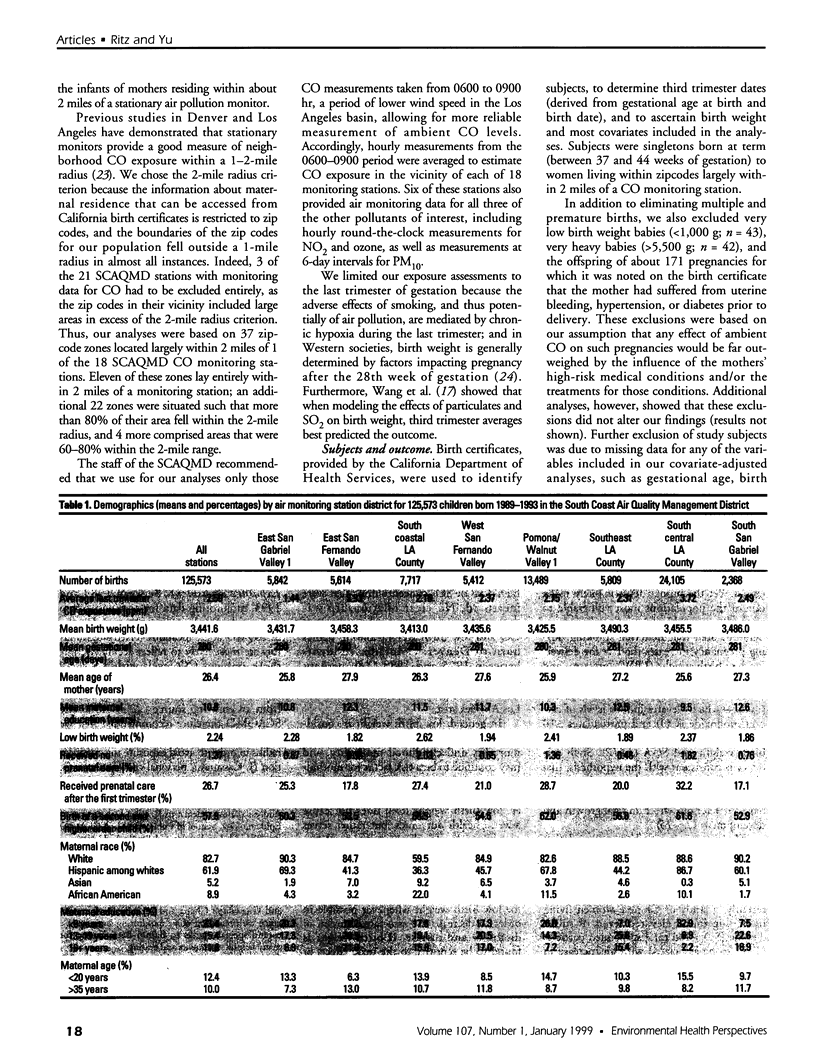

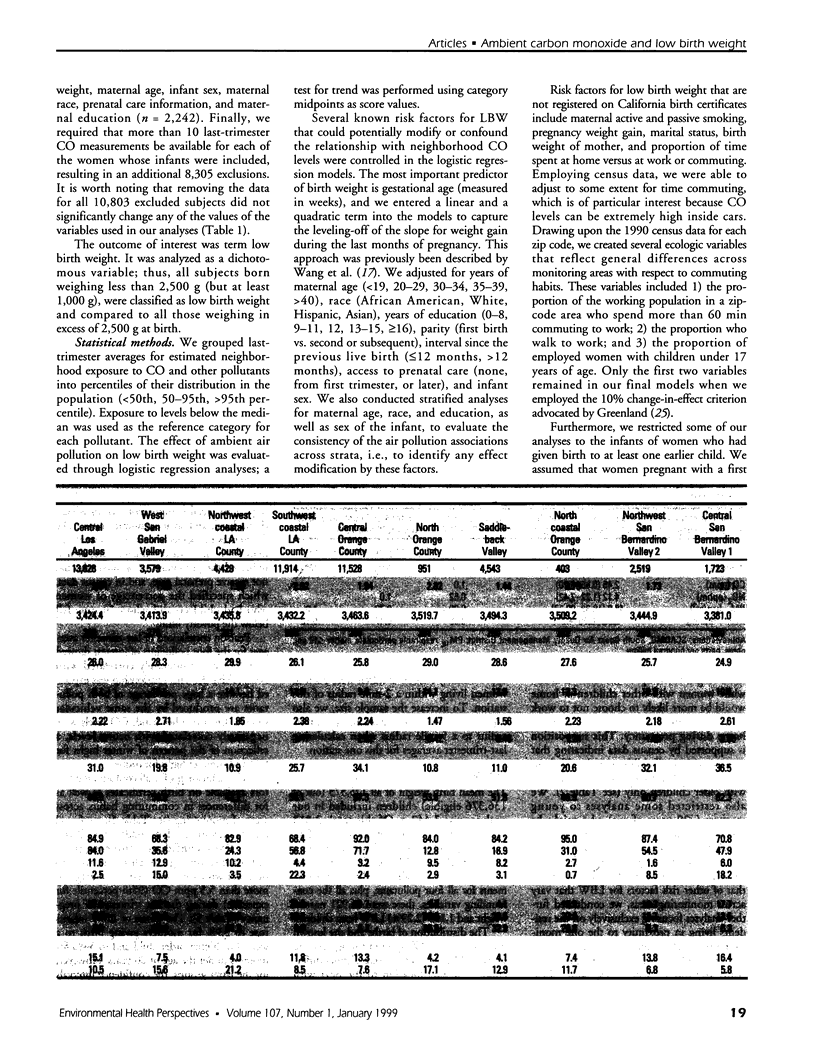

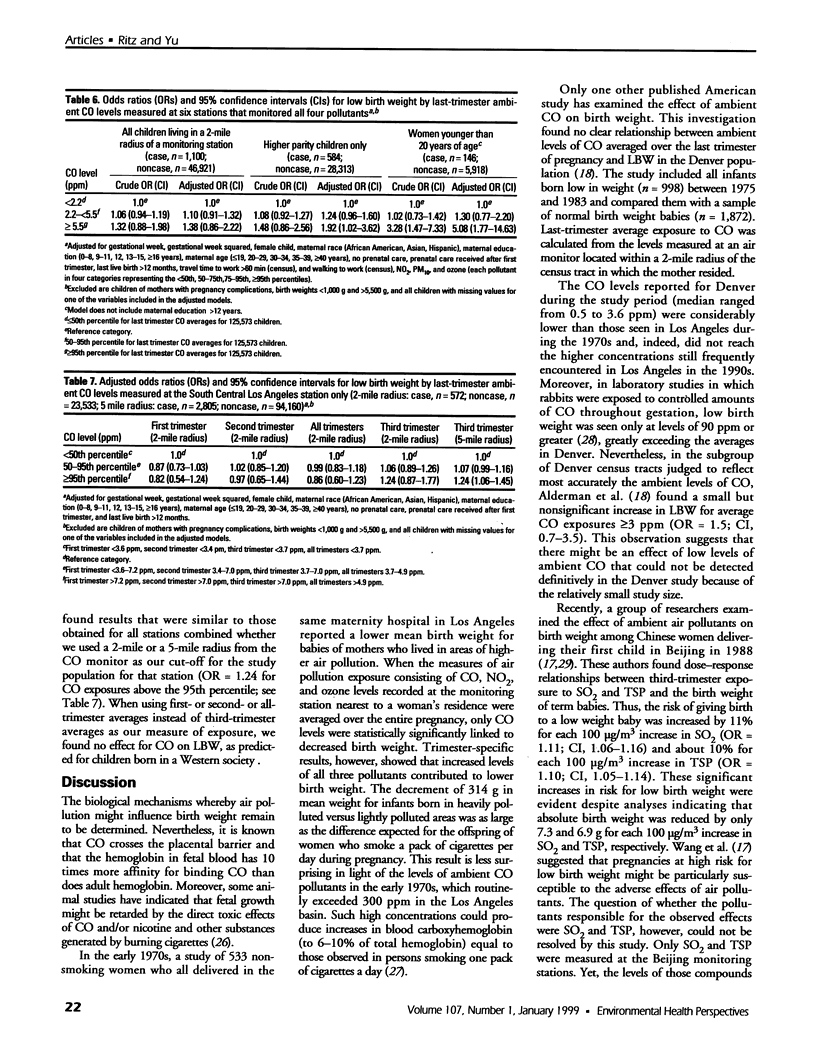

We evaluated the effect of carbon monoxide (CO) exposures during the last trimester of pregnancy on the frequency of low birth weight among neonates born 1989-1993 to women living in the Los Angeles, California, area. Using birth certificate data for that period, we assembled a retrospective cohort of infants whose mothers resided within 2 miles of 1 of 18 CO monitoring stations. Based on the gestational age and birth date of each child, we estimated last-trimester exposure by averaging the corresponding 3 months of daily CO concentrations registered at the monitoring station closest to the mother's residence (determined from the birth certificate). Where data were available (at 6 stations), we also averaged measurements taken daily for nitrogen dioxide and ozone and those taken at 6-day intervals for particulate matter [less than/equal to]10 microm (PM10) to approximate last-trimester exposures to other pollutants. Overall, the study cohort consisted of 125,573 singleton children, excluding infants born before 37 or after 44 weeks of gestation, those weighing below 1,000 or above 5,500 g at birth, those for whom fewer than 10 days of CO measurements were available during the last trimester, and those whose mothers suffered from hypertension, diabetes, or uterine bleeding during pregnancy. Within the cohort, 2,813 (2.2%) were low in birth weight (between 1,000 and 2,499 g). Exposure to higher levels of ambient CO (>5.5 ppm 3-month average) during the last trimester was associated with a significantly increased risk for low birth weight [odds ratio (OR) = 1.22; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.03-1.44] after adjustment for potential confounders, including commuting habits in the monitoring area, sex of the child, level of prenatal care, and age, ethnicity, and education of the mother.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahlborg G., Jr, Bodin L. Tobacco smoke exposure and pregnancy outcome among working women. A prospective study at prenatal care centers in Orebro County, Sweden. Am J Epidemiol. 1991 Feb 15;133(4):338–347. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderman B. W., Baron A. E., Savitz D. A. Maternal exposure to neighborhood carbon monoxide and risk of low infant birth weight. Public Health Rep. 1987 Jul-Aug;102(4):410–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrup P., Olsen H. M., Trolle D., Kjeldsen K. Effect of moderate carbon-monoxide exposure on fetal development. Lancet. 1972 Dec 9;2(7789):1220–1222. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz G. S., Papiernik E. Epidemiology of preterm birth. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(2):414–443. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosley A. R., Sibert J. R., Newcombe R. G. Effects of maternal smoking on fetal growth and nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1981 Sep;56(9):727–729. doi: 10.1136/adc.56.9.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. J., Lewry J., Wailoo M. Further evidence for the effect of passive smoking on neonates. Postgrad Med J. 1988 Sep;64(755):663–665. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.64.755.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnattingius S., Axelsson O., Eklund G., Lindmark G. Smoking, maternal age, and fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1985 Oct;66(4):449–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnattingius S. Does age potentiate the smoking-related risk of fetal growth retardation? Early Hum Dev. 1989 Dec;20(3-4):203–211. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(89)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnattingius S., Forman M. R., Berendes H. W., Graubard B. I., Isotalo L. Effect of age, parity, and smoking on pregnancy outcome: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Jan;168(1 Pt 1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Bremauntz A. A., Ashmore M. R. Exposure of commuters to carbon monoxide in Mexico City II. Comparison of in-vehicle and fixed-site concentrations. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1995 Oct-Dec;5(4):497–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flachsbart P. G. Long-term trends in United States highway emissions, ambient concentrations, and in-vehicle exposure to carbon monoxide in traffic. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1995 Oct-Dec;5(4):473–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier I., Marcoux S., Brisson J. Passive smoking during pregnancy and the risk of delivering a small-for-gestational-age infant. Am J Epidemiol. 1994 Feb 1;139(3):294–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. H., Koepsell T. D., Daling J. R. Birth weight and smoking during pregnancy--effect modification by maternal age. Am J Epidemiol. 1994 May 15;139(10):1008–1015. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989 Mar;79(3):340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph K. S., Kramer M. S. Review of the evidence on fetal and early childhood antecedents of adult chronic disease. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18(2):158–174. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J. M., Lieberman E., Cohen A. A comparison of risk factors for preterm labor and term small-for-gestational-age birth. Epidemiology. 1996 Jul;7(4):369–376. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo L. D. The biological effects of carbon monoxide on the pregnant woman, fetus, and newborn infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977 Sep 1;129(1):69–103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90824-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez F. D., Wright A. L., Taussig L. M. The effect of paternal smoking on the birthweight of newborns whose mothers did not smoke. Group Health Medical Associates. Am J Public Health. 1994 Sep;84(9):1489–1491. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navidi W., Lurmann F. Measurement error in air pollution exposure assessment. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1995 Apr-Jun;5(2):111–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neas L. M., Dockery D. W., Koutrakis P., Tollerud D. J., Speizer F. E. The association of ambient air pollution with twice daily peak expiratory flow rate measurements in children. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Jan 15;141(2):111–122. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott W. R. Human exposure assessment: the birth of a new science. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1995 Oct-Dec;5(4):449–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott W. R., Mage D. T., Thomas J. Comparison of microenvironmental CO concentrations in two cities for human exposure modeling. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1992 Apr-Jun;2(2):249–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebagliato M., Bolumar F., Florey C. du V. Assessment of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in nonsmoking pregnant women in different environments of daily living. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Sep 1;142(5):525–530. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebagliato M., Florey C. du V., Bolumar F. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in nonsmoking pregnant women in relation to birth weight. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Sep 1;142(5):531–537. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J., Khoury M. J., Finucane F. F., Delgado H. L. Differences in the epidemiology of prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. Early Hum Dev. 1986 Dec;14(3-4):307–320. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(86)90193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ding H., Ryan L., Xu X. Association between air pollution and low birth weight: a community-based study. Environ Health Perspect. 1997 May;105(5):514–520. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen S. W., Goldenberg R. L., Cutter G. R., Hoffman H. J., Cliver S. P., Davis R. O., DuBard M. B. Smoking, maternal age, fetal growth, and gestational age at delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jan;162(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90819-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. L., Colome S. D., Tian Y., Becker E. W., Baker P. E., Behrens D. W., Billick I. H., Garrison C. A. California residential air exchange rates and residence volumes. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1996 Jul-Sep;6(3):311–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Ding H., Wang X. Acute effects of total suspended particles and sulfur dioxides on preterm delivery: a community-based cohort study. Arch Environ Health. 1995 Nov-Dec;50(6):407–415. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1995.9935976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Ratcliffe J. M. Paternal smoking and birthweight in Shanghai. Am J Public Health. 1993 Feb;83(2):207–210. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]