Abstract

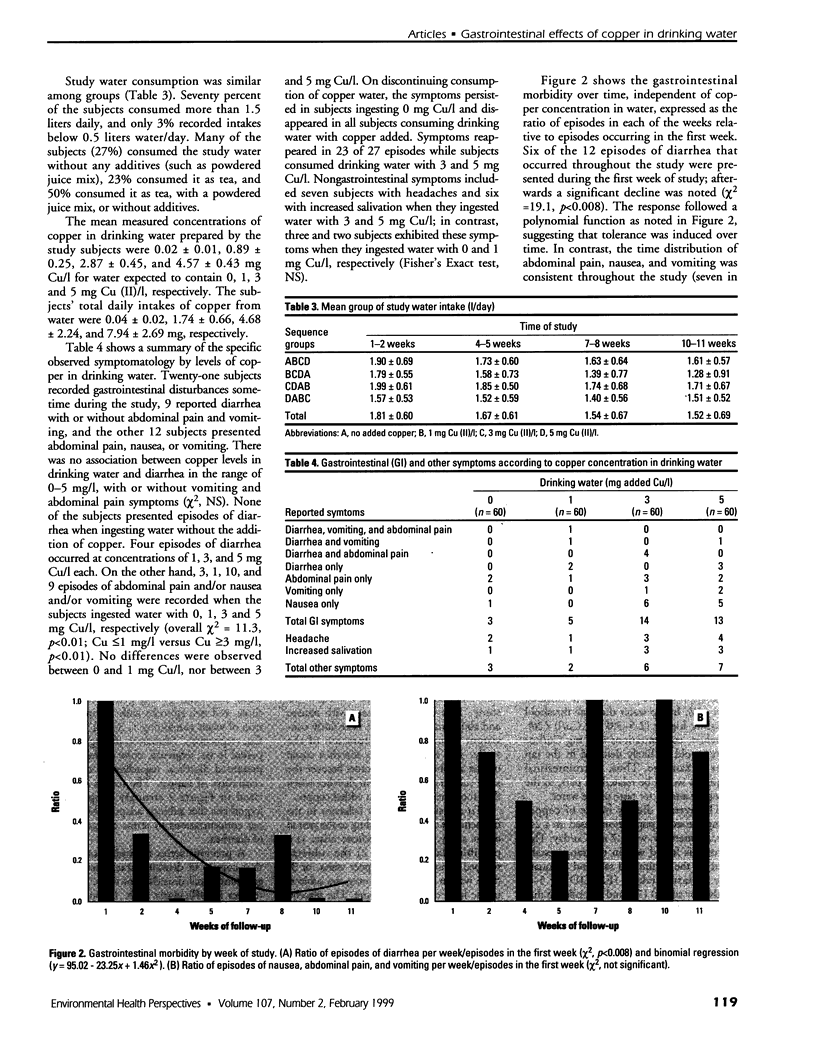

The objective of this study was to determine the acute gastrointestinal effects caused by the consumption of drinking water containing graded levels of added copper. Sixty healthy, adult women were randomly assigned to receive copper [Cu(II)] at four concentrations in their drinking water following a Latin-square design. Each group (n = 15) received tap water with no added copper, 1, 3, and 5 mg Cu/l of added copper sulfate for a 2-week study period, followed by 1 week of standard tap water. The subjects recorded their water consumption and gastrointestinal symptoms daily on a special form. The average daily consumption of water was 1.64 liters per subject, regardless of the amount of copper added. Final serum copper, ceruloplasmin, and liver enzymes were measured in all subjects and were not different from baseline concentrations. Twenty-one subjects (35%) recorded gastrointestinal disturbances sometime during the study, 9 had diarrhea, some with abdominal pain and vomiting, and 12 subjects presented abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting. There was no association between copper levels in drinking water and diarrhea. However, nausea, abdominal pain, or vomiting were significantly related to copper concentrations in water. The recorded incidence rate of these symptoms was 5, 2, 17, and 15% while ingesting water with 0, 1, 3, and 5 mg Cu/l, respectively (overall [chi]2 = 11.3, p<0.01; Cu [less than/equal to]1 mg/l versus Cu [Greater than/equal to]3 mg/l, [chi]2, p<0.01). When subjects interrupted their consumption of drinking water with added copper, most symptoms disappeared. We conclude that under the conditions of the study, there was no association between aggregate copper in drinking water within the range of 0-5 mg/l and diarrhea, but a [Greater than/equal to]3 mg Cu/l level of ionized copper was associated with nausea, abdominal pain, or vomiting. Additional studies with sufficient numbers of subjects are needed to define thresholds for specific gastrointestinal symptoms with precision and to extrapolate these results to the population at large.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ACHAR S. T., RAJU V. B., SRIRAMACHARI S. Indian childhood cirrhosis. J Pediatr. 1960 Nov;57:744–758. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(60)80170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari B., Sharda S. Indian childhood cirrhosis: a search for cause and remedy. Indian J Pediatr. 1984 Mar-Apr;51(409):135–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02825917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobeloch L., Ziarnik M., Howard J., Theis B., Farmer D., Anderson H., Proctor M. Gastrointestinal upsets associated with ingestion of copper-contaminated water. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Nov;102(11):958–961. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder M. C., Hazegh-Azam M. Copper biochemistry and molecular biology. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 May;63(5):797S–811S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luza S. C., Speisky H. C. Liver copper storage and transport during development: implications for cytotoxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 May;63(5):812S–820S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden J. P., Goodman S. J., Guthrie H. A. Validity of the 24-hr. recall. Analysis of data obtained from elderly subjects. J Am Diet Assoc. 1976 Feb;68(2):143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina E., Kaempffer A. M. Morbilidad y atención médica en el Gran Santiago. Rev Med Chil. 1979 Feb;107(2):155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares M., Pizarro F., Speisky H., Lönnerdal B., Uauy R. Copper in infant nutrition: safety of World Health Organization provisional guideline value for copper content of drinking water. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Mar;26(3):251–257. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares M., Uauy R. Limits of metabolic tolerance to copper and biological basis for present recommendations and regulations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 May;63(5):846S–852S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitalny K. C., Brondum J., Vogt R. L., Sargent H. E., Kappel S. Drinking-water-induced copper intoxication in a Vermont family. Pediatrics. 1984 Dec;74(6):1103–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlieb I. Copper and the liver. Gastroenterology. 1980 Jun;78(6):1615–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnlund J. R., Keyes W. R., Anderson H. L., Acord L. L. Copper absorption and retention in young men at three levels of dietary copper by use of the stable isotope 65Cu. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989 May;49(5):870–878. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M., Müller-Höcker J., Wiebecke B., Belohradsky B. H. First description of "Indian childhood cirrhosis" in a non-Indian infant in Europe. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1989 Jan;78(1):152–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1989.tb10908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]