Abstract

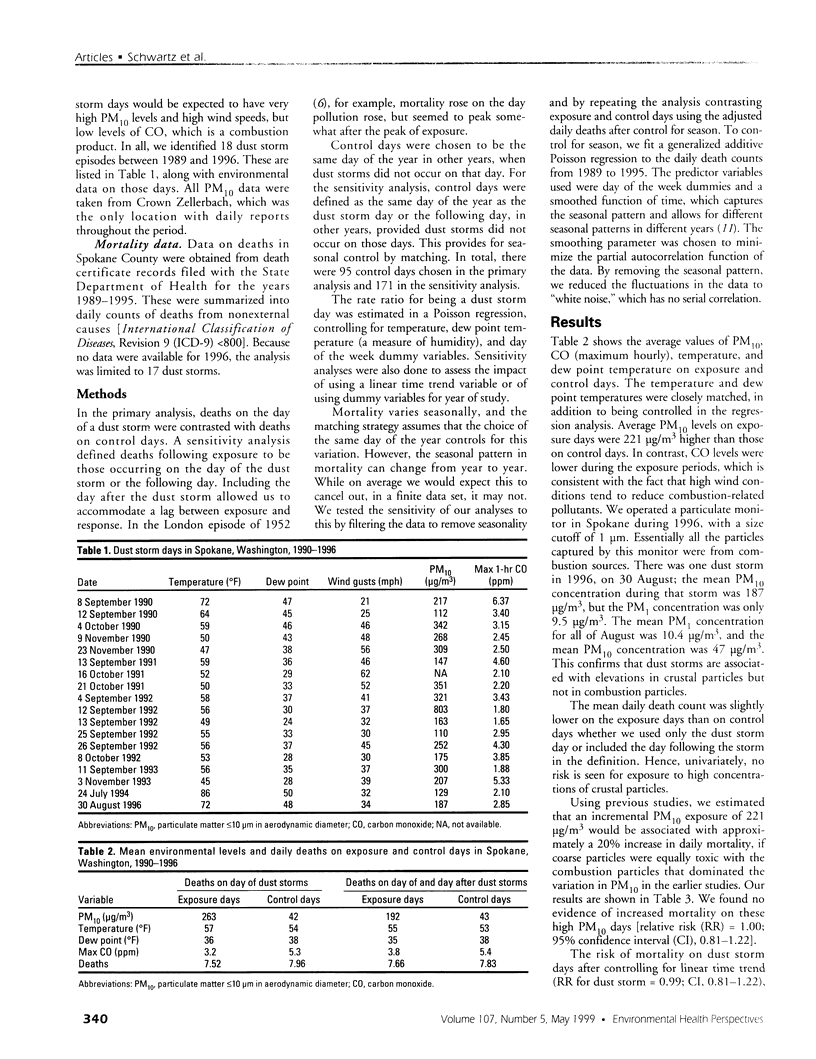

Fine particle concentration (i.e., particles <2.5 microm in aerodynamic diameter; PM2.5), but not coarse particle concentration, was associated with increased mortality in six U.S. cities. Others criticized this result, arguing that it could result from differences in measurement error between the two size ranges. Fine particles are primarily from combustion of fossil fuel, whereras coarse particles (i.e., particles between 2.5 and 10 microm in aerodynamic diameter) are all crustal material, i.e., dust. One way to determine if coarse particles are a risk for mortality is to identify episodes of high concentrations of coarse, but not fine, particles. Spokane, Washington, is located in an arid area and is subject to occasional dust storms after crops have been harvested. Between 1989 and 1995, we identified 17 dust storms in Spokane. The 24-hr mean PM10 concentration during those storms was 263 microg/m3. Using control dates that were the same day of the year in other years (but with no dust storm on that day) and that had a mean PM10 concentration of 42 microg/m3, we compared the rate of nonaccidental deaths on the episode versus nonepisode days. There was little evidence of any risk [relative risk (RR) = 1.00; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.81-1.22] on the episode days. Defining episode deaths as those occurring on the same or following day as the dust storm produced similar results (RR = 1.01; CI, 0.87-1.17). Sensitivity analyses, which tested more extensive seasonal control, produced smaller estimates. We conclude that coarse particles from windblown dust are not associated with mortality risk.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brunekreef B., Janssen N. A., de Hartog J., Harssema H., Knape M., van Vliet P. Air pollution from truck traffic and lung function in children living near motorways. Epidemiology. 1997 May;8(3):298–303. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist A. S., Johnson L. R., Vollmer W. M., Sexton G. J., Kanarek P. H. Acute effects of volcanic ash from Mount Saint Helens on lung function in children. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983 Jun;127(6):714–719. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa D. L., Dreher K. L. Bioavailable transition metals in particulate matter mediate cardiopulmonary injury in healthy and compromised animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 1997 Sep;105 (Suppl 5):1053–1060. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s51053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher K. L., Jaskot R. H., Lehmann J. R., Richards J. H., McGee J. K., Ghio A. J., Costa D. L. Soluble transition metals mediate residual oil fly ash induced acute lung injury. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1997 Feb 21;50(3):285–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour P. S., Brown D. M., Lindsay T. G., Beswick P. H., MacNee W., Donaldson K. Adverse health effects of PM10 particles: involvement of iron in generation of hydroxyl radical. Occup Environ Med. 1996 Dec;53(12):817–822. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.12.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefflin B. J., Jalaludin B., McClure E., Cobb N., Johnson C. A., Jecha L., Etzel R. A. Surveillance for dust storms and respiratory diseases in Washington State, 1991. Arch Environ Health. 1994 May-Jun;49(3):170–174. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9940378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Y., Gilmour P. S., Donaldson K., MacNee W. Free radical activity and pro-inflammatory effects of particulate air pollution (PM10) in vivo and in vitro. Thorax. 1996 Dec;51(12):1216–1222. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.12.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert F. W., Wyzga R. E. Air pollution and mortality: the implications of uncertainties in regression modeling and exposure measurement. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 1997 Apr;47(4):517–523. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1997.10464417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Wichmann H. E., Tuch T., Heinrich J., Heyder J. Respiratory effects are associated with the number of ultrafine particles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997 Apr;155(4):1376–1383. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.4.9105082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. Air pollution and daily mortality: a review and meta analysis. Environ Res. 1994 Jan;64(1):36–52. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1994.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. Air pollution and hospital admissions for heart disease in eight U.S. counties. Epidemiology. 1999 Jan;10(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. Air pollution and hospital admissions for respiratory disease. Epidemiology. 1996 Jan;7(1):20–28. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann H. E., Mueller W., Allhoff P., Beckmann M., Bocter N., Csicsaky M. J., Jung M., Molik B., Schoeneberg G. Health effects during a smog episode in West Germany in 1985. Environ Health Perspect. 1989 Feb;79:89–99. doi: 10.1289/ehp.897989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]