Abstract

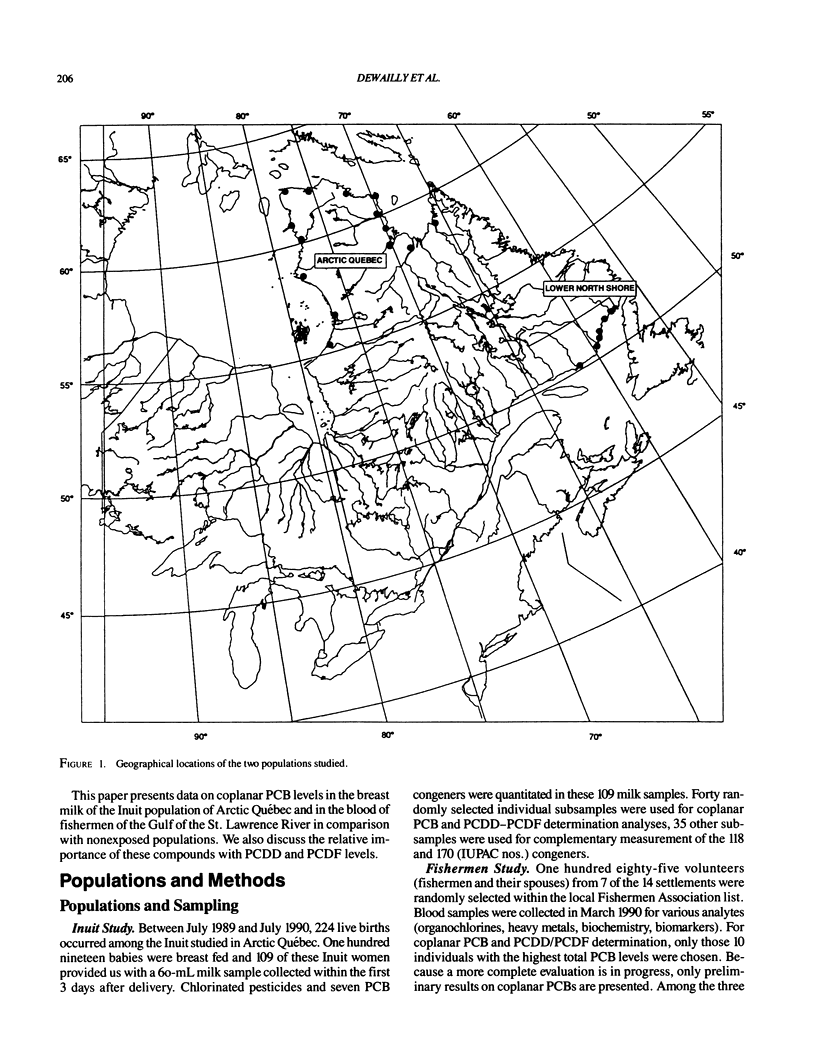

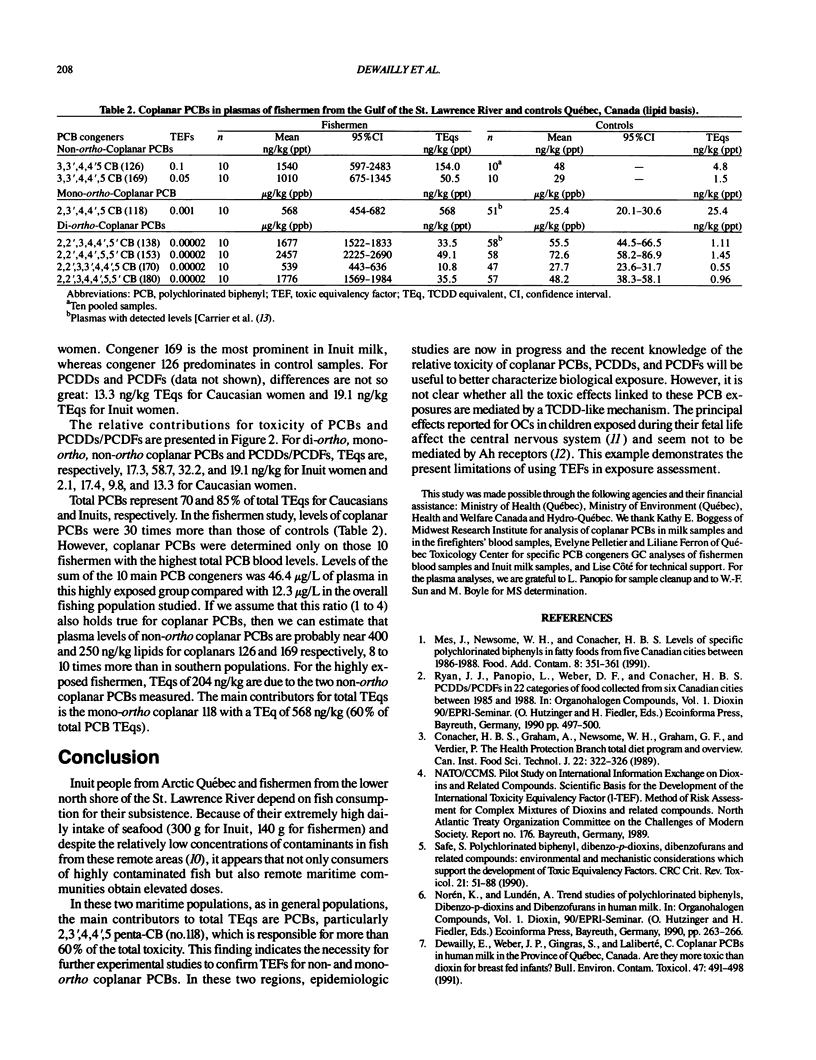

Two remote maritime populations were evaluated for their biological exposure to organochlorines in 1989-1990. Because of their high intake of seafood, these two populations have high biological levels. One hundred nine breast milk samples from Inuit women from Arctic Québec were analyzed to determine levels of polychlorodibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs), polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs), and coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) including non-ortho, mono-ortho, and di-ortho congeners. Total 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin equivalents (TEqs) for PCBs were 3.5 times higher in Inuit milk samples than in 96 Caucasian milk samples. Among the 185 fishermen from the Lower North Shore of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River, we evaluated 10 highly exposed fishermen for their coplanar PCB blood levels. Total TEqs were 900 ng/kg for highly exposed individuals with 36 ng/kg for controls. In these two nonoccupationally exposed populations, coplanar PCBs make a larger contribution to the TEq than PCDDs and PCDFs. However, the mono-ortho penta CB No. 118 is the major contributor for the total toxicity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Dewailly E., Weber J. P., Gingras S., Laliberté C. Coplanar PCBs in human milk in the province of Québec, Canada: are they more toxic than dioxin for breast fed infants? Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1991 Oct;47(4):491–498. doi: 10.1007/BF01700935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J. L., Jacobson S. W., Humphrey H. E. Effects of in utero exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and related contaminants on cognitive functioning in young children. J Pediatr. 1990 Jan;116(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mes J., Newsome W. H., Conacher H. B. Levels of specific polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in fatty foods from five Canadian cities between 1986 and 1988. Food Addit Contam. 1991 May-Jun;8(3):351–361. doi: 10.1080/02652039109373984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir D. C., Wagemann R., Hargrave B. T., Thomas D. J., Peakall D. B., Norstrom R. J. Arctic marine ecosystem contamination. Sci Total Environ. 1992 Jul 15;122(1-2):75–134. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(92)90246-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs), dibenzofurans (PCDFs), and related compounds: environmental and mechanistic considerations which support the development of toxic equivalency factors (TEFs). Crit Rev Toxicol. 1990;21(1):51–88. doi: 10.3109/10408449009089873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]