Abstract

Abasic substitutions in the non-template strand and promoter sequence changes were made to assess the roles of various promoter features in σ70 holoenzyme interactions with fork junction probes. Removal of –10 element non-template single strand bases, leaving the phosphodiester backbone intact, did not interfere with binding. In contrast these abasic probes were deficient in promoting holoenzyme isomerization to the heparin resistant conformation. Thus, it appears that the melted –10 region interaction has two components, an initial enzyme binding primarily to the phosphodiester backbone and a base dependent isomerization of the bound enzyme. In contrast various upstream elements cooperate primarily to stimulate binding. Features and positions most important for these effects are identified.

INTRODUCTION

σ70 dependent bacterial promoters (1–3) contain two moderately conserved hexamers separated by an optimal spacer length of 17 bp. These two recognition elements are near positions –10 and –35 relative to the start site at +1. The elements stabilize polymerase binding to DNA, direct polymerase dependent DNA melting within the –10 element and promote isomerization of the polymerase to its functional heparin-resistant form. Naturally occurring promoters deviate from the consensus resulting in a diverse array of promoter activities (4,5). DNA sequences outside these elements also have a very important influence (6,7).

Recent studies have emphasized that the –10 and –35 elements may have significantly different functions. The –35 region acts through duplex DNA and makes stabilizing contacts to region 4 of the polymerase σ subunit (8). This can help anchor the enzyme to the DNA throughout the preinitiation pathway (9,10). The role of the –10 region is more complex because it is converted to the single stranded form during open complex formation. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) studies using either duplex or fork junction probes (where the –10 region is presented as a non-template single strand) show effects of base substitutions (11). When fork junction probes lacking the –35 region are tested using energy transfer the effects are larger (12). However, when fork junction probes (with –35) are tested by EMSA in the presence of heparin, nucleotide substitutions lead to large defects (11,13). This led to the idea that a primary function of the –10 region is to assist in isomerizing polymerase to the heparin resistant form via interactions with melted DNA (11). The comparisons also point out the importance of DNA context in evaluating the function of the –10 region.

Several studies have suggested that the A on the non-template strand at –11 is of paramount importance for the function of the –10 region DNA element in single stranded form (12–15). The extension of an upstream duplex to include this as a single melted nucleotide confers stability in EMSA assays using fork junction probes (13). The effect is greater when assays measure the ability of the isomerized enzyme to resist heparin challenge. It has been suggested that that this nucleotide performs a ‘gating’ (13) or ‘master’ (16) function during the melting of the promoter DNA. This may be related to its unpairing during the nucleation of the melting process. The unpairing at –11 to create a fork junction is likely to be a seminal event, although how the structure contributes to subsequent events is still unclear. Substitutions at this position can have wide-ranging effects on binding, isomerization and ultimately transcription.

Understanding the roles of sequence-specific recognition of the –10 region nucleotides has been hampered by the lack of a high-resolution structure and by the lack of a uniform context for diverse biochemical experiments. It is clear that many contacts come from the σ subunit (17,18), but it is not clear as to how the effects of these contacts partition before and after the isomerization of the enzyme. It is also not clear how the upstream DNA elements, and the fork junction itself, contribute to –10 function. This is because different experiments have used probes with and without upstream sequences, and in the presence and absence of heparin.

In this report we investigate the effect of upstream sequences and the nature of sequence-specific interactions with the –10 element, with and without heparin challenge. The primary approach uses EMSA on fork junction probes. In one set of experiments various upstream elements are combined to learn their contributions to probe binding. Other experiments use probes in which bases have been removed individually but the backbone remains intact. These allow the assessment of the base-specific interactions in the duplex –35 region and in the single stranded –10 region of the non-template strand. The results show that probes with an intact non-template strand backbone but lacking single bases can be bound quite well, with significant reductions seen only in the presence of heparin. In this circumstance the binding is reduced somewhat more when the abasic site receives a non-consensus base. Overall, the results support a significant role for the –10 region backbone in polymerase binding with a major role for the bases in enzyme isomerization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins and DNA

The plasmid pQE30-rpoD was over-expressed and σ70 was purified as described (19). Escherichia coli RNA polymerase core is a commercial product from Epicenter Technologies. Oligonucleotides and probes were prepared as described (20). Briefly, the bottom strand of each probe was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. The 40-µl mixture, containing 4 pmol of kinased DNA and 6 pmol complementary strand in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5/50 mM NaCl, was annealed by rapid heating to 95°C and slow cooling to room temperature in a PCR thermo cycler (MJ Research). The resulting annealed probes were diluted in Tris–EDTA buffer containing 50 mM NaCl to the desired concentration. Proper annealing was monitored by electrophoresis.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Mobility shift assays with and without heparin were as described (11). Briefly, 20 nM core was mixed with 50 nM σ70 in a 10 µl reaction mixture with 1× buffer A [30 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 100 µg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 3.25% glycerol] with 6 ng/µl (dI-dC) and 1 nM annealed probe, and incubated for 20 min on ice. For heparin challenge experiments, 0.25 µl of 2 mg/ml heparin was added into samples for an additional 5 min (11). Samples were run on 5% PAGE with 1× TBE buffer, packed in ice.

Results

Upstream elements

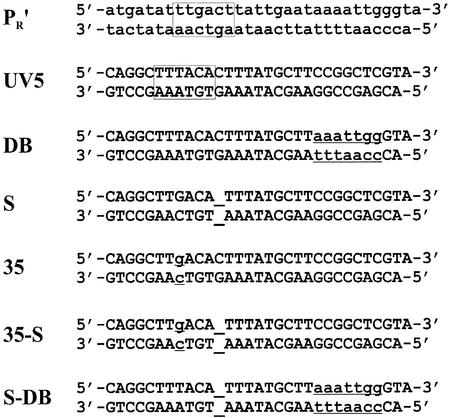

A collection of seven probes is used to assess the importance of the upstream elements in fork probes (Fig. 1). Each probe contains a –35 element and spacer but within the –10 element only base pair –12 and non-template strand nucleotide –11 are present. Previously we found that such a short fork probe modeled after the PR′ promoter can be bound well by RNA polymerase (13) but an analogous UV5 fork probe is bound poorly (11). Differences in PR′ and UV5 fork probes include the spacer and the –35 element. To learn the source of the difference in binding we altered the UV5 probe to include features of PR′. These include changing position –34T in the –35 region to a consensus G, altering the spacer length of 18 bp to an optimal 17 bp, and swapping the upstream PR′ sequence from –14 to –20 into UV5. Pairs of changes were also made in two probes. The collection of five hybrid probes and the two parents are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Parental and hybrid T11/B12 fork junction probes. The parent PR′ (lowercase DNA sequence) and UV5 (uppercase DNA sequence) probes are at the top with the –35 element boxed. DB refers to a PR′ sequence specified as the downstream block (–14 to –20) placed in UV5; S refers to a spacer length change that shortens the UV5 spacer by 1 bp (position –30 deleted, as indicated by an underscore); 35 refers to the indicated change in the UV5 –35 region.

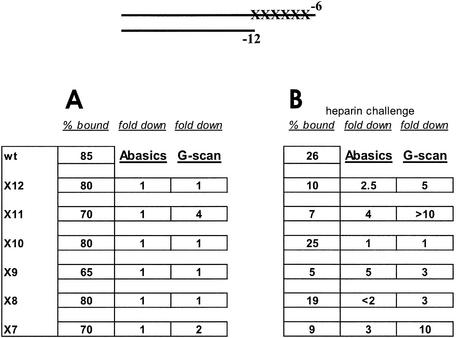

EMSA experiments were done to assess binding on these altered UV5 fork junction probes. The data show that only probes containing pairs of changes formed tightly bound complexes with polymerase (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4). Each of the individual changes also increased binding somewhat (Fig. 2A, lanes 5–7). The –14 to –20 region substitution was slightly better than the spacer length change which in turn was slightly better than the –35 base substitution. It appears that spacer length, non-conserved spacer sequence and the –35 element work together to stabilize binding to fork junction probes.

Figure 2.

EMSA of holoenzyme with fork junction probes shown in Figure 1. Bound complexes are indicated by an arrow. (A) Without heparin: PR′, S-DB, and 35-S bound from 80–95%; S, DB and 35 bound from 20–35%; UV5 did not bind detectably. The lower band in the UV5 lane is representative of core binding. (B) With heparin: PR′ and S-DB, bound from 60–75%; 35-S at ∼30%; DB, S and 35 at 2–10%.

In Figure 2B the experiments were repeated in the presence of heparin. Because the DNA is pre-melted the comparison with Figure 2A bypasses DNA melting and assesses only the ability of the polymerase itself to isomerize to a heparin resistant form. The binding was less but the overall patterns were preserved (compare Fig. 2A with 2B). Thus no upstream feature appears to play a unique role either in DNA binding or in isomerization, but all features are important.

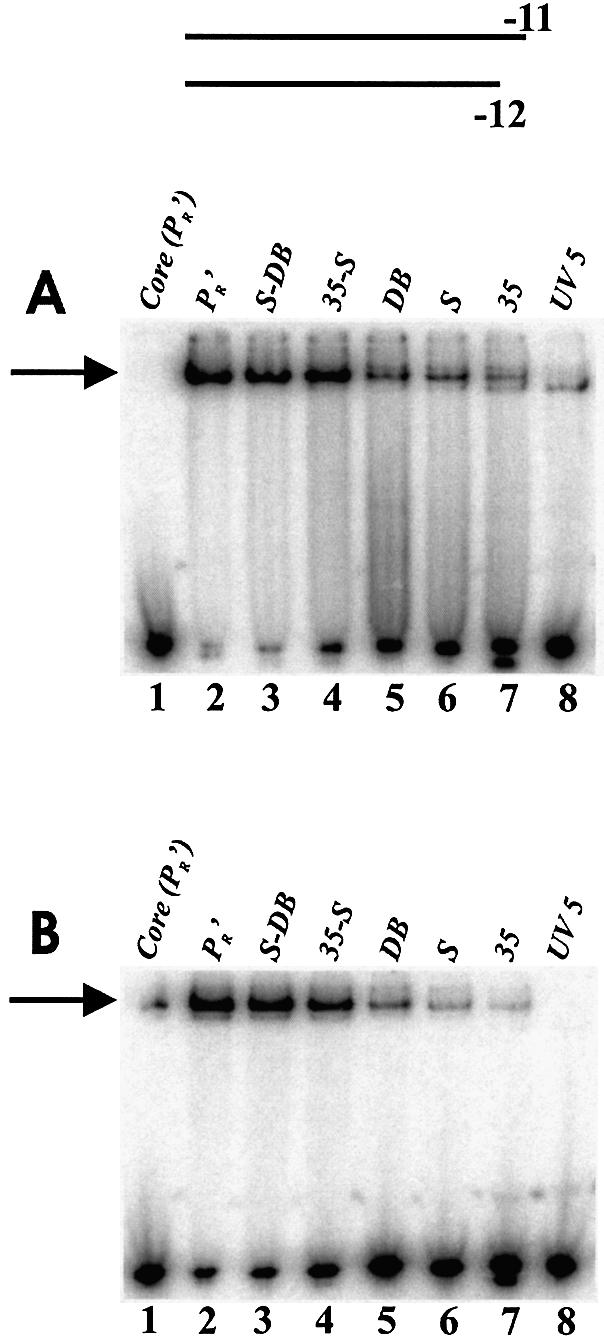

The –35 region is known to be involved in base-specific recognition (21,22). We wished to evaluate the properties of the –35 region bases in a fork junction probe context. The non-template strand was altered in order to provide a direct comparison with studies of the –10 region. Individual bases were deleted, leaving the backbone fully intact, leading to abasic positions in the non-template strand. One of the stronger binding hybrid fork junction probes (35-S) was used in order to reveal partial defects that might occur. The collection of probes contained abasic sites on the non-template strand of the –35 hexamer at each of the six consensus positions (–30 to –35 on the 17 bp spacer 35-S promoter). As a comparison the non-conserved base at position –39 was also made abasic. EMSA experiments were done with and without heparin.

Figure 3A shows that the removal of any one of four out of the six –35 element bases leads to a reduction in binding to fork junction probes (X30A, X32A, X33G and X35T). Removal of either of the other two consensus bases, –31C and –34T, leads to only a slight reduction compared to either the parent or the control probe outside the –35 region (X39). The pattern is similar with and without heparin except that the –30 abasic is somewhat more deleterious in a heparin challenge protocol (compare Fig. 3A with 3B). The data show that some bases are important for fork probe binding but, rather surprisingly, some have a limited importance despite their conservation and the contacts made by their template strand partners to σ (8). Apparently the template strand contacts to –31 and –34 can be maintained in the absence of the non-template base partner.

Figure 3.

EMSA using the 35-S T11/B12 fork junction probes with abasic sites. Abasic sites are at individual positions in the –35 element non- template strand (TTGACA from positions –35 to –30) with a preceding X indicating removal of the specified base. The control used outside the –35 element was at position –39. (A) Without heparin: abasic probes 31, 34 and 39 bound at wild type levels (50% in lane 2), probe 30 bound at 30%, probes 32 and 33 at 15% and probe 35 did not bind detectably. (B) With heparin: probe 39 bound at wild type levels (20% in lane 2), probes 31 and 34 bound at 15%, and binding of probes 30, 32, 33 and 35 was barely detectable.

Removal of the overhanging –11A base from a short fork junction probe

These short fork junction probes contain a single unpaired nucleotide, a consensus A at non-template strand position –11. This –11 nucleotide overhang at the optimal fork junction is required for strong binding (13). The nucleotide must be the consensus A to obtain efficient enzyme isomerization (13). The next experiment tests the contribution of the base and backbone to these properties. A hybrid fork junction probe with a 3′ phosphate on the non-template strand (35-S) was used to obtain the strongest parental signal. The test probe was constructed to be abasic at –11 with the backbone remaining intact.

In the absence of heparin, removal of the base led to a 2- or 3-fold reduction in binding (Fig. 4A, compare lane 3 with 4). In the presence of heparin, the –11 abasic fork junction probe was incapable of enzyme isomerization (Fig. 4B, compare lane 7 with 8). We conclude that the consensus base A at –11, and not just the backbone, is helpful for DNA binding by polymerase. However, the base itself is necessary for polymerase isomerization.

Figure 4.

EMSA using 35-S fork junction probes. The 35-S-P has a phosphate at the 3′ end of the non-template strand and X11 is also abasic at –11. (A) Without heparin: probes 35-S and 35-S-P bound ∼50% and probe X11-P bound ∼20%. (B) With heparin: probes 35-S and 35-S-P bound ∼15% and X11-P did not bind detectably. The core lanes used the 35-S fork probe.

Effects of abasic sites within the melted –10 region

Abasic sites were also introduced into a probe containing a duplex –10 region in order to assess effects on double strand DNA binding. However, binding to all duplex probes was stimulated by the removal of a base (not shown), likely due to the creation of easily melted DNA around the abasic positions. To investigate the roles of bases in single stranded DNA a fork junction probe with a longer single strand tail was used. In such probes the melted non-template strand extends to position –6. The probes with a longer single strand tail bind better than the short fork probes with a one nucleotide overhang under non-saturated binding conditions. When bases and backbones together are progressively removed from such probes binding is strongly decreased (11). Nonetheless, the effects of base substitution are modest on binding; they remain substantial on enzyme isomerization (11).

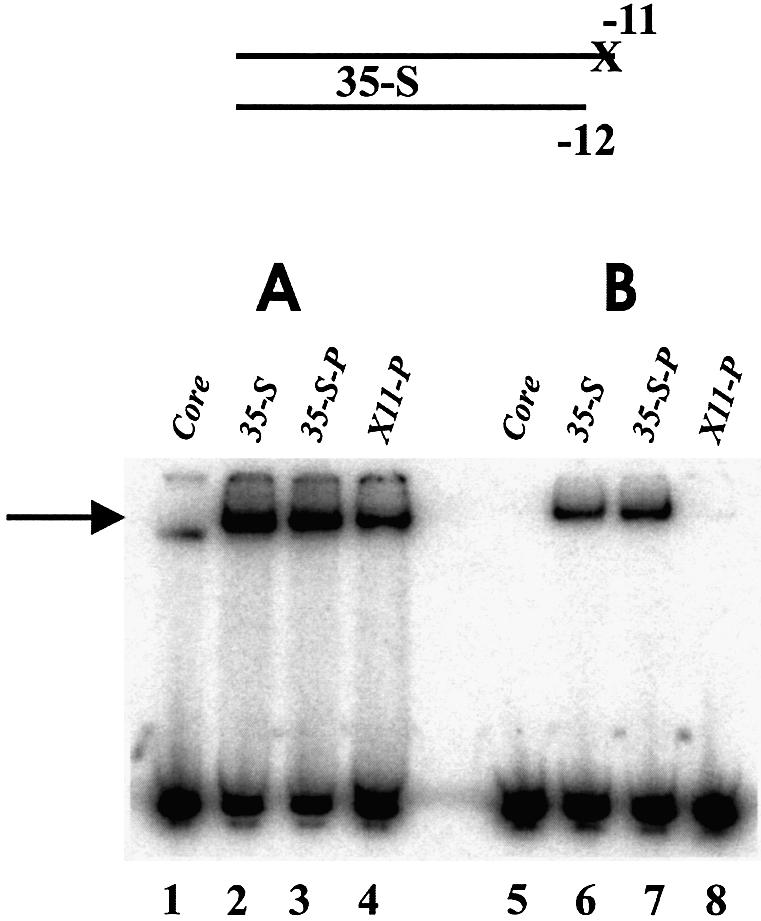

In order to evaluate the contributions of the consensus bases, six abasic probes were created by removal of individual bases from –12 to –7 (Fig. 5 top). The backbone remains intact in all cases. EMSA was done in the absence and presence of heparin. The data was tabulated and is presented in Figure 5. For the sake of comparison, data from prior EMSA experiments (11) where G was substituted at each position is also presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

EMSA on T6/B12 fork + tail probes with abasics in the single strand –10 element. The left column indicates the abasic position (X7 is a probe with an abasic at –7 and so forth). (A) Without heparin and (B) with heparin. The independent data for G substitutions at each positon is reproduced from prior EMSA experiments (11).

Results in the absence of heparin show that individual abasic substitutions have little or no effect on probe binding (Fig. 5A). For example removal of the –7 base had little effect whereas it was shown previously that removal of both the base and backbone led to a large decrease in binding. The results indicate that the backbone is a critical determinant for binding. In comparison, G substitutions show effects at positions –11 and –7 (see Fig. 5A). Because the consensus base can be removed without detectable effect, the comparison suggests that inclusion of a non-consensus base can actively inhibit binding. Strong effects are seen with a probe abasic at both –11 and –7 (data not shown). Thus, although the main binding interaction is with the backbone, the bases present at positions –11 and –7 have an influence on binding.

Experiments that evaluate enzyme isomerization via heparin challenge gave a different picture of the effects of removing bases (Fig. 5B). In this circumstance five of the six probes showed reductions (the abasic at position –10 is the exception). The remaining abasics led to an average 3-fold reduced binding. When compared with data obtained from G substitutions, the results indicate that substitution of a non-consensus base can lead to a weakened signal compared with simple removal of a consensus base. As was the case for binding without heparin challenge this is most clear at positions –11 and –7 (see Fig. 5). Overall, the results suggest that the bases themselves, not just the backbone, are centrally involved in enzyme isomerization.

In order to place these results in the context of intact DNA, –11 and –7 cytosine substitutions were studied on supercoiled plasmid DNA (pTH8-UV5). Occupancy of the mutant promoters was measured via DNase I protection (data not shown). Both mutants (–7C and –11C) led to a partial reduction in protection against DNase I digestion. The reductions in occupancy were reflected in diminished melting as assessed by permanganate reactivity and diminished transcription (data not shown) and the –11C mutation was slightly more defective in all assays. The transcription results with the –11 mutant were consistent with the defects observed in transcription from the PR′ promoter (23). The –7C mutant on lacUV5 was more defective in transcription than on the PR′ promoter, consistent with binding assays that demonstrate the PR′ promoter has more optimal upstream elements (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Overall, the data indicate that binding studies on these probes reflect properties of transcription complexes.

DISCUSSION

DNA binding

The data show that a variety of DNA elements and structures cooperate to promote holoenzyme binding prior to polymerase isomerization. These include the –35 element, the spacer length, the spacer sequence (independent of length), the fork junction structure and the phosphodiester backbone of the non-template strand when the –10 region is melted. No feature appears to be truly unique in that any can be altered and binding still occurs when an optimal combination of the others is present. Some aspects of how they contribute to binding are unusual.

Prior data showed that when the nucleotides of the melted –10 region are removed progressively from position –7, binding is very strongly diminished (11). However, the current data show that when individual bases are removed, leaving the phosphodiester backbone intact, binding levels are not significantly altered (Fig. 5A). Effects can be seen only when multiple bases are removed (data not shown), or when using a weaker-binding truncated probe in which only the –11 nucleotide is melted (Fig. 4). This implies that a large component of the initial binding of holoenzyme to melted DNA involves the DNA backbone. The effects of removing the base at either –11 or –7 are less than when a non-consensus base is substituted [(11) and see Fig. 5B]. This suggests that non-consensuses bases in the –10 regions of natural promoters may interfere with binding by hindering the holoenzyme from properly engaging the melted DNA backbone.

These results are consistent with prior experiments using fork junction probes in which substitutions had modest effects on DNA binding in the absence of heparin (11). Other studies detected more significant reductions in binding upon substitution of non-consensus nucleotides (12,14). These studies used probes that did not contain upstream stabilizing features and thus would allow smaller differences to be detected. The larger effects on enzyme isomerization (see below) were not explored in those investigations.

Removal of non-template stand bases in the duplex –35 promoter region, also leaving the backbone intact, led to variable effects on holoenzyme binding. Significant reductions were seen in four of the six positions (underlined in TTGACA) (Fig. 3). Only the initial –35T appears to be contacted directly in the structure of σ region 4 with short duplex DNA (8). Consistent with this, the removal of the contacted –35T led to a more severe binding defect than at the other three affected positions. It is possible that the other base removals disrupt the DNA helical structure and thus indirectly interfere with polymerase contacts on the template strand. However, removal of either –34T or –31C is without effect so this view is difficult to support except in a strongly localized context. It should be noted that non-consensus bases at these two positions (–35T and –32C at the lacUV5 promoter) lead to a reduction in transcription (24). It may be that the source of these various effects would be more apparent if the overall kinetic pathway of recognition were understood.

Enzyme isomerization

The ability of holoenzyme to isomerize to its functional conformation was assessed using a heparin challenge assay. Because the DNA probes were pre-melted the need to melt DNA is not a part of this assay. Thus, comparing EMSA results on various probes with and without heparin reveals how features of the probes contribute to driving the enzyme into the heparin-resistant conformation.

All of the elements tested were important in obtaining maximal amounts of heparin-resistant binding. There were two experiments in which isomerization was much more affected than binding. When individual bases were removed from the melted –10 region, leaving the backbone intact, large effects were only seen in the heparin challenge protocol (compare Fig. 5A with 5B). With probes containing only the –11 overhanging nucleotide, the reduction caused by removing the base was significantly greater in the presence of heparin than in the absence (Fig. 4, lane 4 versus lane 8). The comparisons indicate that within the melted –10 region DNA the bases themselves, as distinct from the backbone, are important for holoenzyme isomerization. The exception is position –10, which in the fork probe context shows no importance in either binding or isomerization.

The overall data suggest two stages in the use of the melted –10 region DNA during formation of functional open complexes. During the initial stages of opening the holoenzyme could make its most important contacts with the DNA backbone in this region, as suggested by the overall binding data (Fig. 5) (11). The data indicate that the most important contributions at this stage would come from exposure of position –11 (Figs 4 and 5), which would help to create the fork junction. Subsequently, establishment of holoenzyme contacts with most or all of the –10 element bases, along with stabilization provided by upstream interactions, would help to stabilize the isomerized form of the enzyme (Figs 2 and 5). As promoters typically do not have fully consensus –10 sequences or optimal upstream elements they would vary in how easily the isomerization phase would be promoted. This is consistent with prior data on the lacUV5 promoter (25), which was the parent for these studies. In general the degree of binding and the rate of isomerization, set by the combination of these and other promoter features along with activators, would determine the initiation rate for each promoter.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by NIH grant GM35754.

REFERENCES

- 1.deHaseth P.L., Zupancic,M.L. and Record,M.T.,Jr (1998) RNA polymerase–promoter interactions: the comings and goings of RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol, 180, 3019–3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross C.A., Chan,C., Dombroski,A., Gruber,T., Sharp,M., Tupy,J. and Young,B. (1998) The functional and regulatory roles of sigma factors in transcription. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 63, 141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmann J.D. and deHaseth,P.L. (1999) Protein–nucleic acid interactions during open complex formation investigated by systematic alteration of the protein and DNA binding partners. Biochemistry, 38, 5959–5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyle H., Waldburger,C. and Susskind,M.M. (1991) Hierarchies of base pair preferences in the P22 ant promoter. J. Bacteriol, 173, 1944–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youderian P., Bouvier,S. and Susskind,M.M. (1982) Sequence determinants of promoter activity. Cell, 30, 843–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keilty S. and Rosenberg,M. (1987) Constitutive function of a positively regulated promoter reveals new sequences essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 6389–6395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross W., Gosink,K.K., Salomon,J., Igarashi,K., Zou,C., Ishihama,A., Severinov,K. and Gourse,R.L. (1993) A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. Science, 262, 1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell E.A., Muzzin,O., Chlenov,M., Sun,J.L., Olson,C.A., Weinman,O., Trester-Zedlitz,M.L. and Darst,S.A. (2002) Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Mol. Cell, 9, 527–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schickor P., Metzger,W., Werel,W., Lederer,H. and Heumann,H. (1990) Topography of intermediates in transcription initiation of E.coli. EMBO J., 9, 2215–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mecsas J., Cowing,D.W. and Gross,C.A. (1991) Development of RNA polymerase-promoter contacts during open complex formation. J. Mol. Biol., 220, 585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenton M.S. and Gralla,J.D. (2001) Function of the bacterial TATAAT –10 element as single-stranded DNA during RNA polymerase isomerization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 9020–9025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matlock D.L. and Heyduk,T. (2000) Sequence determinants for the recognition of the fork junction DNA containing the –10 region of promoter DNA by E. coli RNA polymerase. Biochemistry, 39, 12274–12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Y. and Gralla,J.D. (1998) Promoter opening via a DNA fork junction binding activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 11655–11660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu J. and Helmann,J.D. (1999) Adenines at –11, –9 and –8 play a key role in the binding of Bacillus subtilis Esigma(A) RNA polymerase to –10 region single-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4541–4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marr M.T. and Roberts,J.W. (1997) Promoter recognition as measured by binding of polymerase to nontemplate strand oligonucleotide. Science, 276, 1258–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim H.M., Lee,H.J., Roy,S. and Adhya,S. (2001) A “master” in base unpairing during isomerization of a promoter upon RNA polymerase binding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 14849–14852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenton M.S., Lee,S.J. and Gralla,J.D. (2000) Escherichia coli promoter opening and –10 recognition: mutational analysis of sigma70. EMBO J., 19, 1130–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomsic M., Tsujikawa,L., Panaghie,G., Wang,Y., Azok,J. and deHaseth,P.L. (2001) Different roles for basic and aromatic amino acids in conserved region 2 of Escherichia coli sigma(70) in the nucleation and maintenance of the single-stranded DNA bubble in open RNA polymerase–promoter complexes. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 31891–31896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson C. and Dombroski,A.J. (1997) Region 1 of sigma70 is required for efficient isomerization and initiation of transcription by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol., 267, 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo Y., Wang,L. and Gralla,J.D. (1999) A fork junction DNA–protein switch that controls promoter melting by the bacterial enhancer-dependent sigma factor. EMBO J., 18, 3736–3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardella T., Moyle,H. and Susskind,M.M. (1989) A mutant Escherichia coli sigma 70 subunit of RNA polymerase with altered promoter specificity. J. Mol. Biol., 206, 579–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegele D.A., Hu,J.C., Walter,W.A. and Gross,C.A. (1989) Altered promoter recognition by mutant forms of the sigma 70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol., 206, 591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts C.W. and Roberts,J.W. (1996) Base-specific recognition of the nontemplate strand of promoter DNA by E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell, 86, 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi M., Nagata,K. and Ishihama,A. (1990) Promoter selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: effect of base substitutions in the promoter –35 region on promoter strength. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 7367–7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stefano J.E. and Gralla,J.D. (1982) Mutation-induced changes in RNA polymerase–lac ps promoter interactions. J. Biol. Chem., 257, 13924–13929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]