Abstract

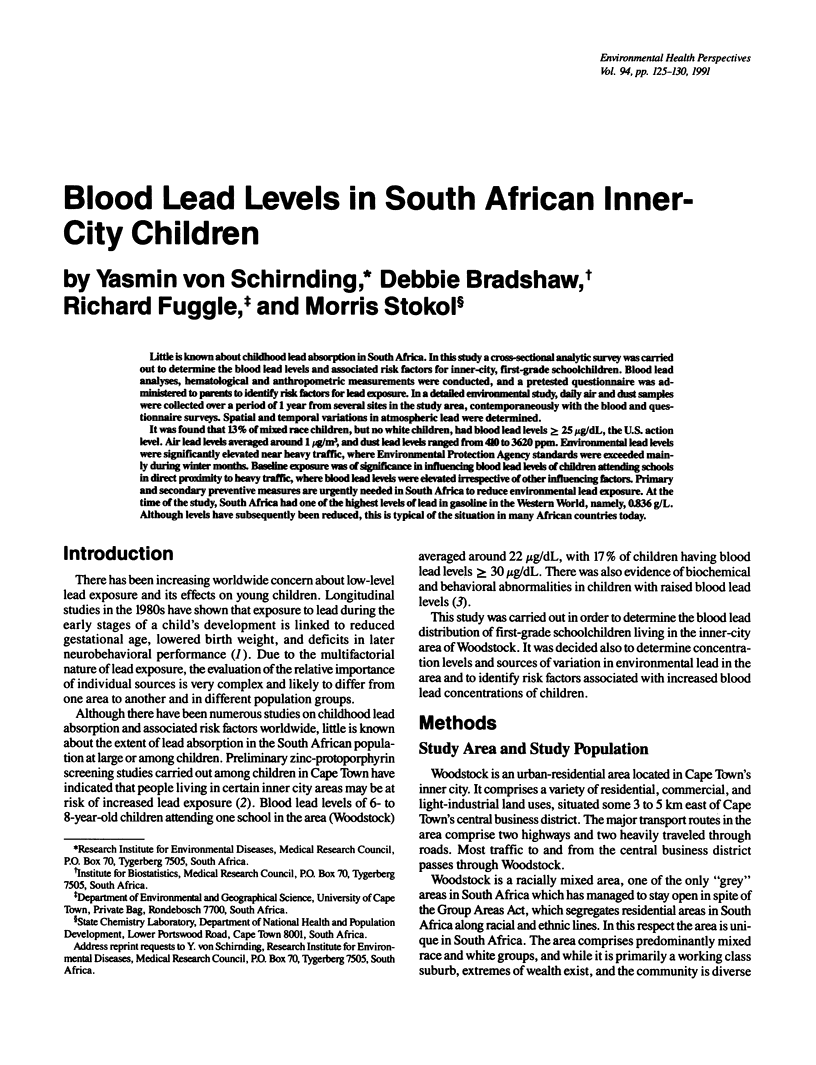

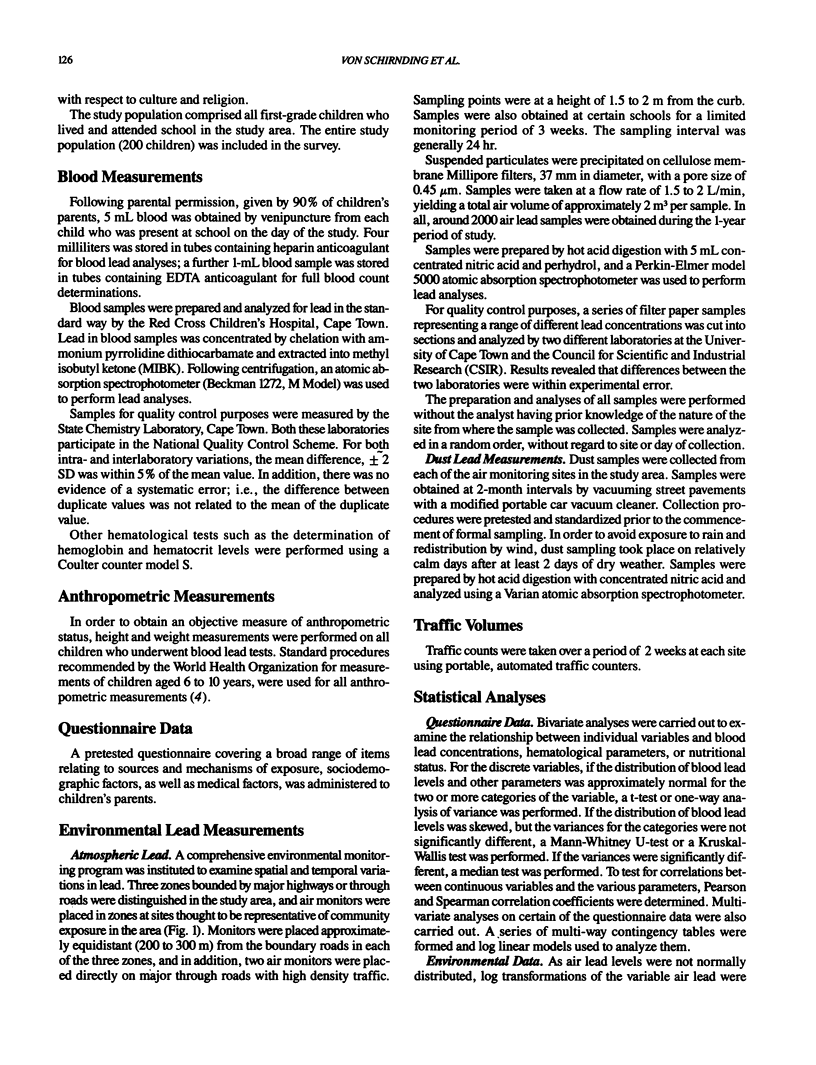

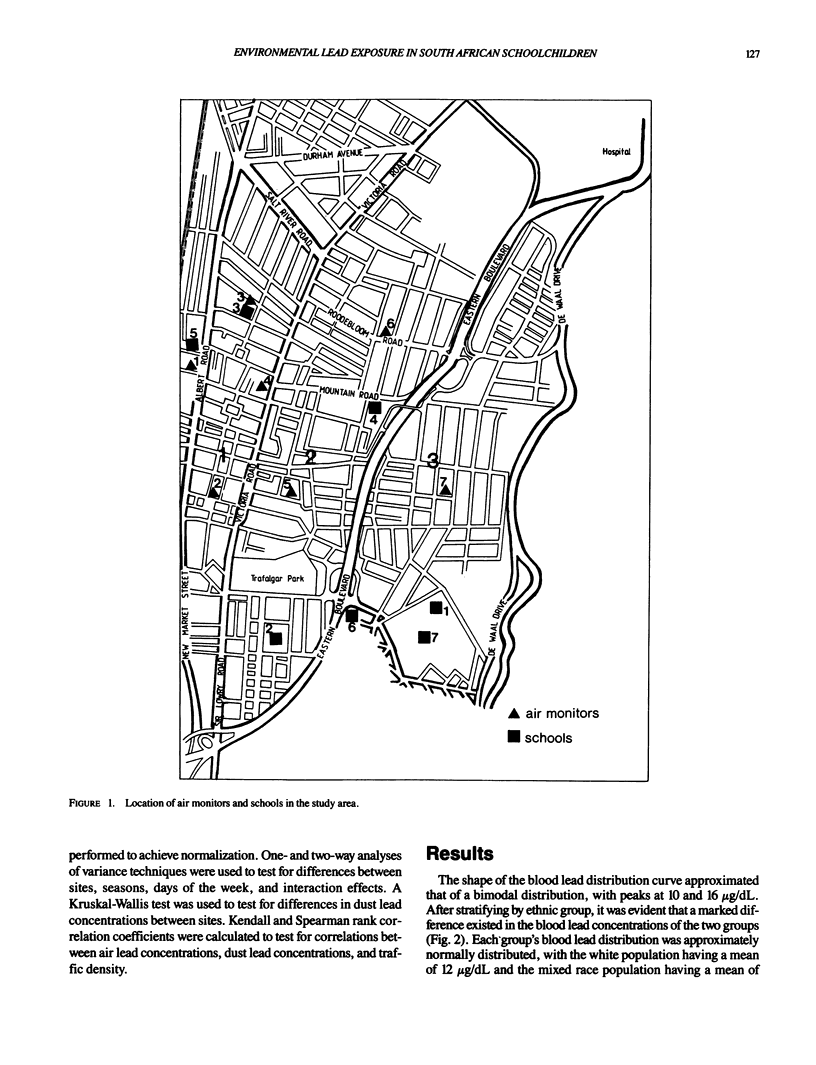

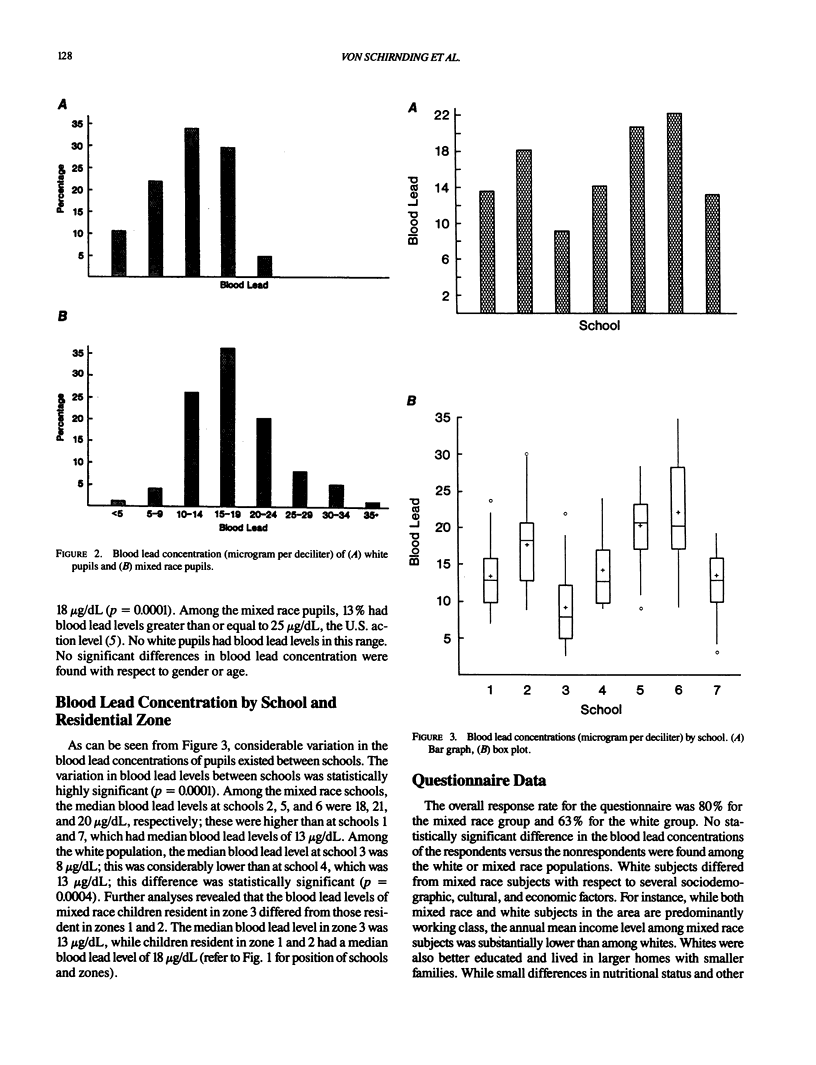

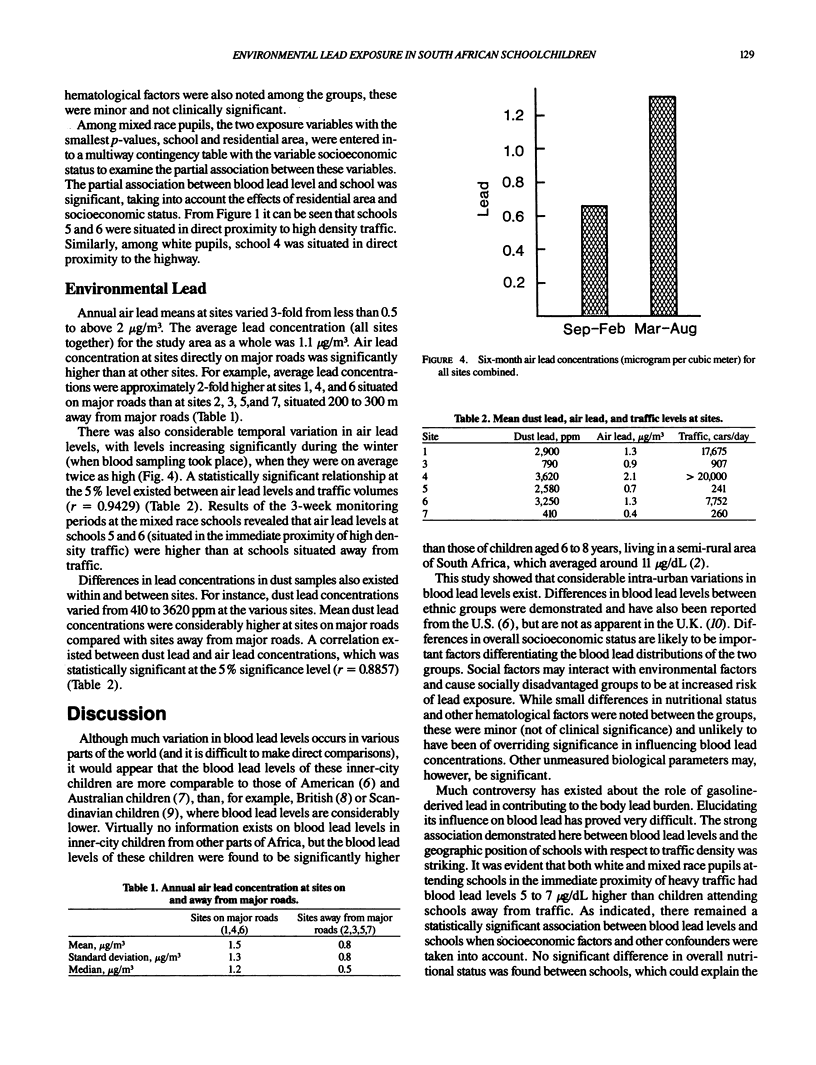

Little is known about childhood lead absorption in South Africa. In this study a cross-sectional analytic survey was carried out to determine the blood lead levels and associated risk factors for inner-city, first-grade schoolchildren. Blood lead analyses, hematological and anthropometric measurements were conducted, and a pretested questionnaire was administered to parents to identify risk factors for lead exposure. In a detailed environmental study, daily air and dust samples were collected over a period of 1 year from several sites in the study area, contemporaneously with the blood and questionnaire surveys. Spatial and temporal variations in atmospheric lead were determined. It was found that 13% of mixed race children, but no white children, had blood lead levels greater than or equal to 25 micrograms/dL, the U.S. action level. Air lead levels averaged around 1 microgram/m3, and dust lead levels ranged from 410 to 3620 ppm. Environmental lead levels were significantly elevated near heavy traffic, where Environmental Protection Agency standards were exceeded mainly during winter months. Baseline exposure was of significance in influencing blood lead levels of children attending schools in direct proximity to heavy traffic, where blood lead levels were elevated irrespective of other influencing factors. Primary and secondary preventive measures are urgently needed in South Africa to reduce environmental lead exposure. At the time of the study, South Africa had one of the highest levels of lead in gasoline in the Western World, namely, 0.836 g/L. Although levels have subsequently been reduced, this is typical of the situation in many African countries today.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bellinger D., Leviton A., Waternaux C., Needleman H., Rabinowitz M. Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med. 1987 Apr 23;316(17):1037–1043. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunekreef B. The relationship between air lead and blood lead in children: a critical review. Sci Total Environ. 1984 Sep;38:79–123. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(84)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. M., Svendsgaard D. J. Lead and child development. Nature. 1987 Sep 24;329(6137):297–300. doi: 10.1038/329297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M. J. Contribution of lead in dust to children's blood lead. Environ Health Perspect. 1983 Apr;50:371–381. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8350371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey K. R., Annest J. L., Roberts J., Murphy R. S. National estimates of blood lead levels: United States, 1976-1980: association with selected demographic and socioeconomic factors. N Engl J Med. 1982 Sep 2;307(10):573–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198209023071001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan B. M. School blood lead levels. Med J Aust. 1982 Jan 23;1(2):57–57. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1982.tb132138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn M. J. Factors affecting blood lead concentrations in the UK: results of the EEC blood lead surveys, 1979-1981. Int J Epidemiol. 1985 Sep;14(3):420–431. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerfving S., Schütz A., Ranstam J. Decreasing lead exposure in Swedish children, 1978-84. Sci Total Environ. 1986 Dec 31;58(3):225–229. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(86)90201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]