Abstract

Dominant mutations of transmembrane channel-like gene 1 (TMC1) cause progressive sensorineural hearing loss in humans and Beethoven (Tmc1Bth/+) mice. Here we show that Tmc1Bth/+ mice on a C3HeB/FeJ strain background have selective degeneration of inner hair cells while outer hair cells remain structurally and functionally intact. Inner hair cells primarily function as afferent sensory cells, whereas outer hair cells are electromotile amplifiers of auditory stimuli that can be functionally assessed by distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) analysis. When C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth is crossed with either C57BL/6J or DBA/2J wild-type mice, F1 hybrid Tmc1Bth/+ progeny have increased hearing loss associated with increased degeneration of outer hair cells and diminution of DPOAE amplitudes but no difference in degeneration of inner hair cells. We mapped at least one quantitative trait locus (QTL), Tmc1m1, for DPOAE amplitude on chromosome 2 in [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ backcross progeny, and three other QTL on chromosomes 11 (Tmc1m2), 12 (Tmc1m3), and 5 (Tmc1m4) in [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ progeny. The polygenic basis of outer hair cell degeneration in Beethoven mice provides a model system for the dissection of common, complex hearing loss phenotypes, such as presbycusis, that involve outer hair cell degeneration in humans.

THERE are >100 loci at which mutations cause monogenic nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in humans (Friedman and Griffith 2003). Most autosomal recessive loci are associated with prelingual severe to profound SNHL, whereas autosomal dominant alleles typically cause postlingual progressive SNHL (Griffith and Friedman 2002). The specific causes of SNHL associated with advanced age (presbycusis) are unknown, but thought to comprise a complex combination of genetic and environmental factors (Schultz et al. 2005). Mutant mice are important tools for identifying these factors, their function in the auditory system, and the pathogenesis of hearing loss (Haider et al. 2002). For example, studies of polygenic age-related hearing loss in inbred mouse strains (Noben-Trauth et al. 2003) facilitated the recent identification of a genetic modifier of hearing loss in humans (Schultz et al. 2005), demonstrating the applicability of mouse models to the dissection of complex hearing loss traits in humans.

Dominant and recessive mutations of transmembrane channel-like gene 1 (TMC1) cause nonsyndromic SNHL at the DFNA36 and DFNB7/B11 loci, respectively (Kurima et al. 2002, 2003). TMC1 encodes a polytopic transmembrane protein of unknown function that is expressed in cochlear hair cells (Kurima et al. 2002; Vreugde et al. 2002). In mice, dominant and recessive mutations of Tmc1 cause SNHL in the Beethoven (Bth) and deafness (dn) mouse lines, respectively (Kurima et al. 2002; Vreugde et al. 2002). Whereas DFNB7/B11 and dn homozygotes have severe to profound congenital hearing loss, heterozygous carriers of Bth and DFNA36 mutations have delayed-onset, progressive SNHL. SNHL in Beethoven and deafness mice is associated with rapid degeneration of cochlear hair cells (Bock and Steel 1983; Vreugde et al. 2002), indicating that Tmc1 is required for normal hair cell function or survival.

The mammalian cochlea contains two types of hair cells distinguished by their location, morphology, and function (Frolenkov et al. 2004). In general terms, inner hair cells (IHCs) have primarily afferent innervation and function as sensory cells transducing and transmitting auditory signals to the central nervous system. Outer hair cells (OHCs) receive principally efferent innervation and have a distinctive electromotile property postulated to underlie active biomechanical amplification of auditory stimuli. As a result of this active amplification, OHCs generate sounds known as otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) that can be measured noninvasively in living humans and mice with a sensitive microphone in the external auditory canal. In contrast, evaluation of hearing levels by auditory brainstem response (ABR) threshold analysis is an overall measure of peripheral auditory function, including both inner and outer hair cell function. Primary damage or secondary degeneration of OHCs characterizes many common hearing loss phenotypes, such as presbycusis, in humans. Since genetic modifiers are excellent candidates for etiologic determinants of these complex traits (Friedman et al. 2000; Schultz et al. 2005), including presbycusis, we sought to identify modifiers of hair cell degeneration in Beethoven mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals:

All protocols were approved by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Animal Care and Use Committee. Isogenic heterozygous Beethoven (Tmc1Bth/+) mice on C3HeB/FeJ (C3H) (Vreugde et al. 2002) were intercrossed to generate homozygous (C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth), heterozygous (C3H-Tmc1Bth/+), and wild-type (C3H-Tmc1+/+) animals. C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth homozygotes were crossed with wild-type C57BL/6J or DBA/2J mice to generate (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ and (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ hybrids, respectively. F1 hybrids were backcrossed to wild-type parental strains to generate [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ and [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ Beethoven progeny.

Tmc1 genotype analysis:

Genomic DNA was prepared from tail clip biopsies by a phenol/chloroform extraction procedure. A 213-bp fragment of Tmc1 exon 13 was amplified with forward (5′-TAT TAA AGGGAC CGC TCT GAA AAC-3′) and reverse (5′-ATC CAT CAA GGC GAG AAT GAA TAC-3′) primers in a 20-μl volume containing 50 ng DNA, 20 pmol of each primer, 200 μmol/liter of each dNTP, 1.5 mmol/liter MgCl2, and 1.6 units Taq DNA polymerase. Amplification conditions comprised an initial 2-min denaturation at 95°, followed by 30 step-cycles of 30 sec at 95°, 30 sec at 57°, and 45 sec at 72°, with a final elongation of 5 min at 72°. PCR products were directly sequenced on an automated sequencer (ABI-PRISM, model 3700; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

ABR and distortion product otoacoustic emissions analyses:

ABR thresholds were measured as described (Szymko-Bennett et al. 2003) with some modifications: we used alternating polarity click and tone-burst stimuli of 47-μsec and 5-msec duration, respectively. The number of stimulus presentations was varied from 128 to 1024 depending on signal-to-noise ratio, and suprathreshold stimulus intensities were initially decreased in 10-dB steps followed by 5-dB steps at lower intensities to determine the response threshold. When no waveform was detectable at the highest stimulus level of 90 dB sound pressure level (SPL), the threshold was considered to be 95 dB SPL for subsequent analyses.

Distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) were recorded with an acoustic probe (ER-10C; Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL) using DP2000 DPOAE measurement system version 3.0 (Starkey Laboratory, Eden Prairie, MN). Two primary tones with frequency ratio f2/f1 = 1.2 were presented at intensity levels L1 = 65 dB SPL and L2 = 55 dB SPL. f2 was varied in one-sixth-octave steps from ∼4 to 16 kHz. DP-grams comprised 2f1-f2 DPOAE amplitudes as a function of f2. Due to the limited frequency response of the acoustical transducers of the ER-10C probe, the software was able to correct stimulus intensities only at frequencies <16 kHz. Therefore, reliable DPOAE measurements were possible only at f2 frequencies <16 kHz. Table 1 shows the numbers of mice tested by ABR and DPOAE analyses.

TABLE 1.

Number of mice tested in ABR and DPOAE analyses

| Age (wk)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain-genotype | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 |

| C3H-Tmc1+/+ | 0/21 | 10/12 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 9/14 | 5/5 | 11/11 | ||

| (C/B)F1-Tmc1+/+ | 0/6 | 6/6 | 11/11 | 11/11 | 10/10 | ||||

| (C/D)F1-Tmc1+/+ | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | ||||||

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth | 0/6 | 5/7 | 4/4 | ||||||

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ | 0/15 | 15/15 | 0/15 | 0/14 | 12/12 | 15/15 | 11/11 | 11/11 | 10/10 |

| (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ | 0/12 | 12/12 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 15/20 | 27/27 | 17/17 | 17/17 | |

| (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ | 15/15 | 0/15 | 14/14 | 14/14 | 11/11 | 11/11 | |||

Number of mice tested in both ABR and DPOAE analyses are shown on the left and total number of mice tested by ABR analysis are shown on the right.

Histologic analysis:

Organ of Corti specimens were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with Alexa Fluor 568 phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) to visualize hair cells and stereocilia as described (Belyantseva et al. 2005). Inner and outer hair cells were counted in a central segment of each of three regions at 10–20, 40–50, and 70–80% of the total cochlear duct distance from the apex, approximately corresponding to frequency ranges of 7–8, 15–18, and 36–42 kHz (Viberg and Canlon 2004), respectively. Each segment contained a sum total of ∼80 hair cell positions/row with an intact, degenerated, or lost hair cell. Hair cells were counted in at least six mutant or four control ears for each genotype and developmental time point and were considered to be degenerated if the cell soma or stereocilia were absent. Table 2 shows the numbers of mice examined histologically.

TABLE 2.

Number of mice examined histologically

| Distance from apex

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain-genotype | Age (wk) | 10–20% | 40–50% | 70–80% |

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ | 4 | 11 | 7 | 7 |

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth | 4 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| C3H-Tmc1+/+ | 4 | 8 | 7 | 4 |

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ | 8 | 10 | 9 | 6 |

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth | 8 | 10 | 7 | 7 |

| C3H-Tmc1+/+ | 8 | 8 | 7 | 4 |

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ | 12 | 15 | 13 | 8 |

| C3H-Tmc1+/+ | 12 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ | 20 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| C3H-Tmc1+/+ | 20 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ | 8 | 10 | 8 | 7 |

| (C/B)F1-Tmc1+/+ | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ | 8 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| (C/D)F1-Tmc1+/+ | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

Short tandem repeat genotype analysis:

Short tandem repeat (STR) markers (listed in Table 3) spanning the mouse genome were selected at ∼20-cM intervals. The Jackson Laboratory Mouse Genome Informatics website (http://www.informatics.jax.org/) was the source of genetic map positions of STR markers. We analyzed additional markers (listed in Table 4) at loci with significant or suggestive linkage. PCR amplification conditions comprised an initial denaturation step of 95° for 2 min, 33 step-cycles of 95° for 30 sec, 51–60° for 30 sec, and 72° for 45 sec, followed by a final elongation at 72° for 5 min. Amplification products were separated by 3% agarose (NuSieve 3:1; Cambrex Bio Science Rockland, Rockland, ME) gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining and ultraviolet illumination.

TABLE 3.

STR markers used in genomewide QTL association analysis

| Marker | Map position (cM) | Marker | Map position (cM) | Marker | Map position (cM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1Mit212 | 21 | D7Mit56 | 2.5 | D14Mit140 | 14.5 |

| D1Mit132 | 43.1 | D7Mit247 | 16 | D14Mit63a | 22.5 |

| D1Mit442 | 63.1 | D7Mit318 | 37 | D14Mit262b | 28.4 |

| D1Mit15 | 87.9 | D7Mit 105 | 65 | D14Mit92 | 45 |

| D1Mit223 | 106.3 | ||||

| D8Mit190b | 21 | D15Mit102 | 7 | ||

| D2Mit464a | 9.5 | D8Mit301a | 32 | D15Mit128 | 26 |

| D2Mit369b | 27.3 | D8Mit162 | 37 | D15Mit105 | 48 |

| D2Mit323 | 31.7 | D8Mit215 | 59 | D15Mit246 | 60.1 |

| D2Mit92 | 41.4 | D8Mit280 | 72 | ||

| D2Mit444 | 65.8 | D16Mit38 | 28.5 | ||

| D2Mit307 | 74.9 | D9Mit224 | 17 | D16Mit30 | 36 |

| D2Mit59 | 86 | D9Mit208 | 35 | D16Mit76b | 43 |

| D9Mit308 | 49 | D16Mit50a | 53.5 | ||

| D3Mit221 | 2.4 | D9Mit137 | 66 | ||

| D3Mit333 | 22 | D17Mit164 | 4 | ||

| D3Mit77 | 49.7 | D10Mit80 | 4 | D17Mit51 | 23 |

| D3Mit292 | 72.9 | D10Mit106 | 17 | D17Mit238 | 35 |

| D10Mit115 | 38.4 | D17Mit155 | 55 | ||

| D4Mit236 | 12.1 | D10Mit180 | 64 | ||

| D4Mit53 | 19.8 | D18Mit94 | 17 | ||

| D4Mit26 | 42.5 | D11Mit2 | 2.4 | D18Mit105 | 25 |

| D4Mit134 | 62.3 | D11Mit313 | 28 | D18Mit40 | 37 |

| D4Mit190 | 79 | D11Mit320 | 43 | D18Mit80b | 50 |

| D11Mit288 | 55 | D18Mit128a | 55 | ||

| D5Mit349 | 8 | D11Mit253 | 71 | ||

| D5Mit394 | 34 | D19Mit68 | 6 | ||

| D5Mit205 | 45 | D12Mit270 | 13 | D19Mit41 | 16 |

| D5Mit23 | 54 | D12Mit52 | 32 | D19Mit11 | 41 |

| D5Mit292 | 80 | D12Mit20 | 58 | D19Mit91 | 47 |

| D6Mit268 | 15.6 | D13Mit266 | 16 | ||

| D6Mit146 | 38.5 | D13Mit64 | 30 | ||

| D6Mit366 | 50.5 | D13Mit226 | 59 |

Used only in [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice.

Used only in [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice.

TABLE 4.

QTX statistics for QTL affecting DPOAE amplitude

| Symbol | Tmc1m1 | Tmc1m2 | Tmc1m3 | Tmc1m4 | — | — |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 2 | 11 | 12 | 5 | 15 | 17 |

| Position (cM) | 46 | 55 | 3 | 61 | 60 | 25 |

| LOD score | 5.8 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

| Variance (%) | 16 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| Protective allelea | C | C | C | C | B | B |

| Susceptibility allelea | B | D | D | D | C | C |

Dashes indicate loci that did not reach statistical significance.

Strain alleles: C, C3HeB/FeJ; B, C57BL/6J; D, DBA/2J.

QTL association analysis:

The 2f1-f2 DPOAE amplitudes of P56 N2 mice were determined at three frequencies (f2 = 12,609, 14,156, and 15,891 Hz) in both ears. These frequencies correspond to a cochlear duct region ∼40% of the total duct distance from the apex (Viberg and Canlon 2004). The average of the six DPOAE values was analyzed for association with STR marker genotypes on a Macintosh computer with QTX software downloaded from http://www.mapmanager.org/mmQTX.html (Manly et al. 2001). The significance threshold of likelihood ratio statistic (LRS) = 12.4 for interval mapping was estimated by the Quick Test application of QTX (Manly et al. 2001). Conventional base-10 LOD scores were calculated by dividing the LRS by 4.61 (Manly et al. 2001).

Statistical analysis:

The significance of differences in ABR thresholds and DPOAE amplitudes was calculated by Mann–Whitney U testing with Stat View version 4.51 software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA) on a Macintosh computer.

RESULTS

Hearing thresholds:

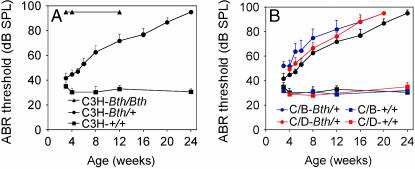

The mouse auditory system is functionally mature by 3 weeks of age (Ehret 1977). At 3 weeks of age, homozygous C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth mice had no detectable ABR to click stimuli, whereas C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ mice had slightly elevated thresholds in comparison to C3H-Tmc1+/+ littermates (Figure 1A). C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ ABR thresholds for both click and tone-burst stimuli steadily increased to reach undetectable levels by 24 weeks of age, whereas C3H-Tmc1+/+ thresholds remained stable (Figure 1; tone-burst response thresholds not shown). These results are consistent with reported compound action potential threshold recordings indicating the semidominant nature of Tmc1Bth (Vreugde et al. 2002).

Figure 1.—

Mean click-evoked ABR thresholds for right ears of Beethoven mice. (A) ABR thresholds for isogenic Tmc1+/+ (C3H-+/+), Tmc1Bth/+ (C3H-Bth/+), and Tmc1Bth/Bth (C3H-Bth/Bth) mice. (B) ABR thresholds for (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/B-Bth/+), (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/D-Bth/+), (C/B)F1-Tmc1+/+ (C/B-+/+), and (C/D)F1-Tmc1+/+ (C/D-+/+) hybrid mice. ABR thresholds for isogenic C3H-Tmc1+/+ and C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ mice are shown as in A. When responses were undetectable with a 95 dB SPL stimulus, the threshold was calculated and presented as 95 dB SPL. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations.

To determine if strain background affects phenotypic expression of Tmc1Bth, we crossed C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth with either DBA/2J or C57BL/6J mice and evaluated auditory function of F1 hybrid progeny from 3 weeks to 20 weeks of age (Figure 1B). In comparison to isogenic C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ mice, (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ ABR click thresholds were modestly but significantly higher (P = 0.0016, 4 weeks; P < 0.0001, 8 weeks; P = 0.0001, 12 weeks; P = 0.0007, 16 weeks; P < 0.0001, 20 weeks). (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ click thresholds were intermediate between those of C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ and (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ mice from 4 to 12 weeks of age, but still significantly higher than C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ thresholds at all but one of these developmental time points: P = 0.0055, 4 weeks; P = 0.0718, 8 weeks; P = 0.02, 12 weeks; P = 0.0003, 16 weeks; P < 0.0001, 20 weeks. (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ click thresholds were significantly lower than (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ thresholds only at the 8- and 12-week time points: P = 0.2134, 4 weeks; P = 0.0009, 8 weeks; P = 0.0019, 12 weeks; P = 0.9625, 16 weeks; P > 0.9999, 20 weeks. Figure 1B shows that these strain background effects on ABR thresholds were largely specific for Tmc1Bth/+ mice since similar differences were not observed with C3H-Tmc1+/+ mice in comparison to (C/B)F1-Tmc1+/+ (P = 0.4824, 4 weeks; P = 0.6222, 8 weeks; P = 0.2908, 24 weeks) or (C/D)F1-Tmc1+/+ mice (P = 0.4606, 4 weeks; P = 0.6222, 8 weeks; P = 0.0361, 24 weeks).

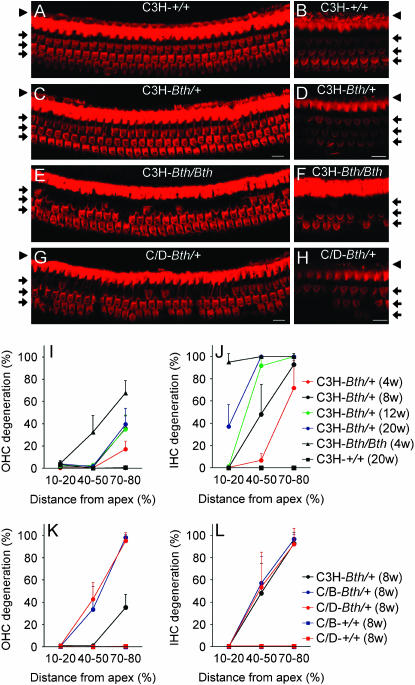

Cochlear hair cell degeneration:

We evaluated IHC and OHC degeneration in basal, middle, and apical regions of the cochlear ducts of isogenic Beethoven mice. At 4 weeks of age, C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth cochleae had nearly complete IHC degeneration in all three regions, whereas OHCs showed a tonotopic gradient of degeneration with a few percent degeneration in the apical duct, 30% in the middle turn, and 70% in the basal turn (Figure 2). In contrast, C3H-Tmc1+/+ cochleae had no degeneration of IHCs or OHCs at 20 weeks of age. C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ hair cells showed an intermediate phenotype. At all developmental time points, C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ OHC degeneration was limited to the basal region, progressing from 20% degeneration at 4 weeks of age to 40% at 20 weeks of age. C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ IHC degeneration was partial (70%) and mainly restricted to the basal region at 4 weeks of age, but increased in a base-to-apex direction with increasing age. By 20 weeks of age, IHC degeneration was essentially complete in the basal and middle regions, and 40% complete in the apical region.

Figure 2.—

Cochlear hair cell degeneration in P56 Beethoven mice. Phalloidin staining of the middle cochlear turn shows the single row of inner hair cells (arrowhead) and three rows of outer hair cells (arrows) in organs of Corti from (A and B) isogenic Tmc1+/+ (C3H-+/+), (C and D) Tmc1Bth/+ (C3H-Bth/+), (E and F) Tmc1Bth/Bth (C3H-Bth/Bth) mice, and (G and H) (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/D-Bth/+) hybrids. Both hair cell somata (A, C, E, and G) and stereocilia (B, D, F, and H) are lost in Tmc1Bth organs of Corti. Bars, 10 μm. (I) Percentage of outer hair cell degeneration and (J) inner hair cell degeneration in apical (10–20%), middle (40–50%), and basal (70–80%) regions of the cochlear duct are shown for isogenic Tmc1+/+ (C3H-+/+) at 20 weeks of age, Tmc1Bth/Bth (C3H-Bth/Bth) at 4 weeks of age, and Tmc1Bth/+ (C3H-Bth/+) mice at multiple time points. (K) Percentage of outer hair cell degeneration and (L) inner hair cell degeneration for (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/B-Bth/+), (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/D-Bth/+), (C/B)F1-Tmc1+/+ (C/B-+/+), and (C/D)F1-Tmc1+/+ (C/D-+/+) hybrid mice at 8 weeks of age. All data points for C/D-+/+ and C/B-+/+ exactly overlap at 0% OHC degeneration in K and L. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations.

To identify strain-dependent effects on hair cell degeneration, we compared isogenic C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ mice with (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ and (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ hybrids at 8 weeks of age. There were no detectable differences in the degree or location of IHC degeneration (Figure 2). However, there was greater OHC degeneration in the hybrid groups in comparison to the isogenic mutants: 100 vs. 35% degeneration in the basal region and ∼40 vs. 0% in the middle region, respectively. There were no significant differences in OHC degeneration between the two hybrid groups: P = 0.3068, apical; P = 0.2477, middle; P = 0.9639, basal. Whereas OHC degeneration was similar among the three rows at any particular location in both hybrid groups, the inner row was most affected and the outer row was least affected in C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ cochleae (not shown).

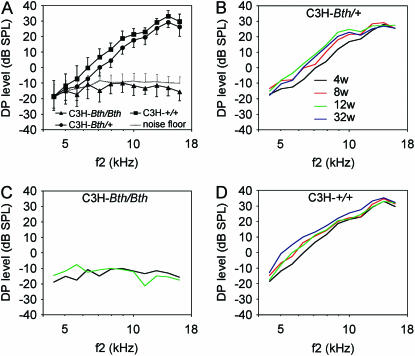

Outer hair cell function:

We measured DPOAEs to determine the effect of strain background on OHC function in Beethoven mice. Four- and 12-week-old C3H-Tmc1Bth/Bth mice had DPOAE amplitudes that were not different from the noise floor of −10 to −20 dB SPL (Figure 3, A and C) in comparison to robust DPOAEs of >30 dB SPL that increased slightly in amplitude from 4 through 32 weeks of age in Tmc1+/+ mice (Figure 3, A and D). C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ DPOAEs had a similar configuration and age dependence (Figure 3, A and B) but with ∼5 dB lower amplitudes than wild-type DPOAEs at most frequencies. At 4 weeks of age, these differences were significant (P < 0.05) for all f2 frequencies above ∼5 kHz. There were no differences at low f2 frequencies since even wild-type DPOAEs are typically undetectable above acoustic noise for f2 ≤ 5 kHz (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.—

Mean distortion product otoacoustic emissions in isogenic Beethoven mice. DP-grams for (A) isogenic Tmc1+/+ (C3H-+/+), Tmc1Bth/+ (C3H-Bth/+), and Tmc1Bth/Bth (C3H-Bth/Bth) mice at 4 weeks of age; (B) Tmc1Bth/+ (C3H-Bth/+) at 4, 8, 12, and 32 weeks of age; (C) Tmc1Bth/Bth (C3H-Bth/Bth) at 4 and 12 weeks of age; (D) Tmc1+/+ (C3H-+/+) at 4, 8, 12, and 32 weeks of age. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations. Data were included for both ears of each animal.

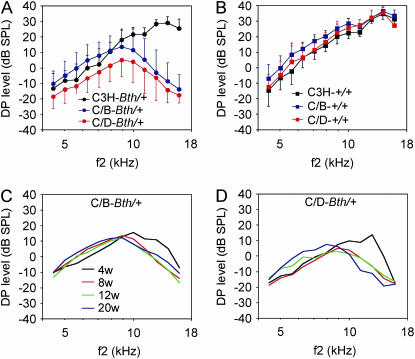

In comparison to C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ mice, DPOAE amplitudes were significantly decreased at the higher measured f2 frequencies in (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (P < 0.0001 for f2 = 11,203, 12,609, 14,156, and 15,891 Hz) and (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ mice (P < 0.0001 for f2 = 8906, 9984, 11,203, 12,609, 14,156, and 15,891 Hz) (Figure 4A). DPOAE amplitudes were significantly (P < 0.01) higher in (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ mice than in (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ mice only at lower f2 frequencies (4453, 5016, 5625, 6281, 7078, 7922, and 8906 Hz). The decrease in these DPOAE amplitudes in the hybrid mutant groups occurred between 4 and 8 weeks of age (Figure 4, C and D). Corresponding DPOAE amplitudes in F1 hybrid wild-type controls were identical or slightly increased in comparison with isogenic wild-type controls (Figure 4B), indicating the effect of background strain on DPOAE amplitudes is specific for heterozygous carriers of Tmc1Bth/+.

Figure 4.—

Mean distortion product otoacoustic emissions in F1 hybrid Beethoven mice. DP-grams for (A) (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/B-Bth/+) and (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/D-Bth/+) hybrids, and Tmc1Bth/+ (C3H-Bth/+) isogenic mice, at 8 weeks of age; (B) (C/B)F1-Tmc1+/+ (C/B-+/+) and (C/D)F1-Tmc1+/+ (C/D-+/+) hybrid mice and Tmc1+/+ (C3H-+/+) isogenic mice at 8 weeks of age; (C) (C/B)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/B-Bth/+) and (D) (C/D)F1-Tmc1Bth/+ (C/D-Bth/+) hybrid mice at 4, 8, 12, and 20 weeks of age. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations. Data were included for both ears of each animal.

Modifier loci:

The different phenotypes of isogenic and hybrid Tmc1Bth/+ mice suggested the existence of one or more modifier loci with strain-specific alleles that differentially affect OHC degeneration caused by Tmc1Bth. It also indicated that, for at least one modifier locus, DBA/2J and C57BL/6J alleles are dominant or semidominant in trans with C3HeJ/FeB alleles. We therefore backcrossed F1 hybrids to their parental strains and analyzed DPOAEs in their N2 offspring at 8 weeks of age. We initially observed a multimodal distribution of DPOAE amplitudes in [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ and [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice that suggested the existence of dominant or semidominant DBA/2J and C57BL/6J alleles at one or two modifier loci (not shown). Total or near-total loss of DPOAEs in [(C/D)F1 × D]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ and [(C/B)F1 × B]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ progeny were consistent with a semidominant model (not shown).

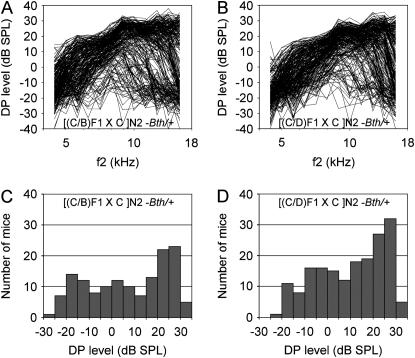

To map loci modifying OHC degeneration in Tmc1Bth/+ mice, we measured DPOAEs of 144 [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ and 180 [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ backcross progeny (Figure 5). The continuous distribution of DP-grams was not consistent with a simple model of mono- or digenic inheritance of modifier alleles, so we analyzed a three-frequency DPOAE amplitude average as a quantitative trait (see materials and methods). The heritability of this trait was 0.82 in [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice and 0.86 in [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice. The subtotal heritability is consistent with the degree of variation of DPOAE amplitudes in F1 hybrid mice (Figure 4).

Figure 5.—

Distortion product otoacoustic emissions in Beethoven backcross progeny. (A and B) DP-grams and (C and D) corresponding histograms for [(C/B)F1 × C)]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ (A and C) and [(C/D)F1 × C)]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ (B and D) backcross progeny at 8 weeks of age. Data were included for both ears of each animal.

Short tandem repeat genotypes were determined in 15 mice with the highest DPOAE amplitude averages and 15 mice with the lowest averages among the N2 progeny of each backcross. These selective genotype analyses identified a potential locus (Tmc1m1) on chromosome 2 in the C57BL/6J backcross and a locus (Tmc1m2) on chromosome 11 in the DBA/2J backcross (not shown). Genotypes of remaining backcross progeny at these loci revealed only weak associations with DPOAE amplitude, indicating that additional loci probably contribute to modification of OHC loss in Tmc1Bth/+ mice. Due to the selection for N2 mice carrying Tmc1Bth, which is located on chromosome 19, STR markers on chromosome 19 inherited from the F1 parent were nearly always C3HeB/FeJ alleles in linkage disequilibrium with Tmc1.

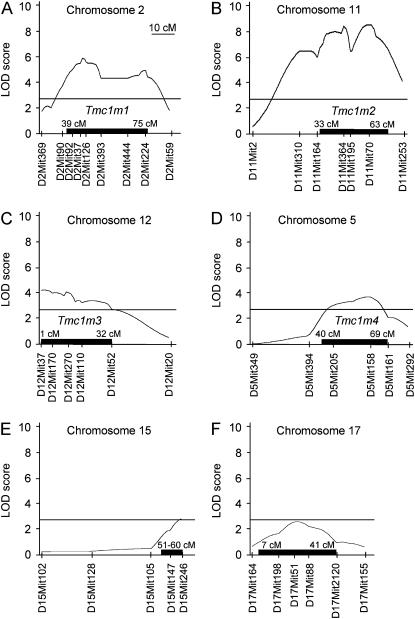

To detect additional modifier loci, we performed a genomewide QTL association analysis on a total of 144 [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ and 125 [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ backcross progeny (Table 5, Figure 6). Interval mapping confirmed the strong association on chromosome 11 in the DBA/2J backcross progeny (Figure 6B) and weaker but significant association with chromosome 2 in the C57BL/6J backcross progeny (Figure 6A). Although the appearance of two peaks might indicate that more than one locus may exist in each interval, genotype analysis of additional markers (listed in Table 4) and additional animals (55 [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice) could not significantly demonstrate the existence of two distinct loci within either broad interval. Tmc1m1 and Tmc1m2 accounted for 16 and 19% of the observed trait variation in the respective N2 backcross progeny (Table 5). We also detected significant associations of reduced DPOAE amplitudes with DBA/2J alleles of markers on chromosomes 12 (Tmc1m3; Figure 6C) and 5 (Tmc1m4; Figure 6D) that accounted for 10 and 9% of the observed trait variation, respectively (Table 5). Finally, we observed suggestive associations, which failed to reach statistical significance, of increased DPOAE amplitudes with C57BL/6J alleles of markers on chromosomes 15 (Figure 6E) and 17 (Figure 6F) that could account for 9 and 8%, respectively, of the observed trait variation (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

STR markers used for fine-mapping of QTL

| [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+

|

[(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Map position (cM) | Marker | Map position (cM) |

| D2Mit90 | 37 | D5Mit24 | 60 |

| D2Mit37 | 45 | D5Mit158 | 62 |

| D2Mit126 | 47.5 | D5Mit424 | 65 |

| D2Mit100 | 47.5 | D5Mit161 | 70 |

| D2Mit481 | 51.4 | ||

| D2Mit101 | 52.5 | D11Mit310 | 24 |

| D2Mit393 | 53.6 | D11Mit164 | 32 |

| D2Mit164 | 71 | D11Mit157 | 34.25 |

| D2Mit224 | 74 | D11Mit177 | 36 |

| D11Mit4 | 37 | ||

| D15Mit147 | 55.3 | D11Mit364 | 44 |

| D11Mit40 | 46 | ||

| D17Mit198 | 16 | D11Mit195 | 47 |

| D17Mit88 | 29.5 | D11Mit36 | 47.64 |

| D17Mit120 | 42 | D11Mit70 | 54 |

| D17Mit142 | 47.4 | D11Mit14 | 57 |

| D12Mit37 | 1 | ||

| D12Mit170 | 6 | ||

| D12Mit283 | 11 | ||

| D12Mit221 | 16 | ||

| D12Mit110 | 19 | ||

| D12Mit190 | 28 | ||

Figure 6.—

Associations of DPOAE amplitude with STR markers in Beethoven backcross progeny. Multipoint LOD plots show significant associations with markers on chromosome 2 (A) in 144 [(C/B)F1 × C)]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice and chromosomes 11 (B), 12 (C), and 5 (D) in 180 [(C/D)F1 × C)]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice. There are suggestive associations with markers on chromosomes 15 (E) and 17 (F). Solid lines, significant LOD levels; solid bars, 1.5-LOD support intervals.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that IHCs selectively degenerate while OHCs are relatively preserved in heterozygous Beethoven mice on the C3HeB/FeJ strain background. Another deaf mouse mutant, Bronx waltzer, also exhibits selective IHC loss with intact DPOAEs (Horner et al. 1985; Schrott et al. 1991). Bronx waltzer has been localized to chromosome 5 (Bussoli et al. 1997) but the underlying gene has not been reported. Although homozygous deafness (Tmc1dn/dn) mice were previously reported to lack DPOAEs, this may reflect age- and strain-dependent effects on OHCs since the tested mice were 40–50 days old and the strain background was not indicated (Horner et al. 1985). Alternatively, the loss of DPOAEs in Tmc1dn/dn mice may result from the homozygous mutant Tmc1 genotype, since homozygous Beethoven mice also lack DPOAEs (Figure 3).

The combination of intact OHC function with elevated hearing thresholds in human patients has been referred to as auditory dyssynchrony or auditory neuropathy (Starr et al. 1996), which can also affect speech perception ability. Auditory neuropathy is a misleading misnomer when a similar phenotype, albeit with better speech perception, results from IHC dysfunction. It is unknown if DFNA36 or DFNB7/B11 phenotypes clinically present with intact DPOAEs. However, speech perception is not affected in DFNA36 (Makishima et al. 2004), while the onset, severity, and nonauditory communication rehabilitation of DFNB7/B11 subjects prohibits assessment of their speech perception (Kurima et al. 2002). Only two autosomal nonsyndromic hearing loss loci in humans are known to be associated with an auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony phenotype: one is autosomal dominant (AUNA1) (Kim et al. 2004) and the other is autosomal recessive (DFNB9) (Rodriguez-Ballesteros et al. 2003; Varga et al. 2003). The contributions of these loci to the genetic load of nonsyndromic auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony are unknown, and it remains possible that some other cases might be caused by TMC1 mutations.

In comparison to isogenic C3H-Tmc1Bth/+ mice, we observed a different pattern of Tmc1Bth/+ hair cell degeneration on C57BL/6J or DBA2/J F1 hybrid backgrounds. Although IHC degeneration was essentially unchanged, OHCs degenerated more rapidly in a base-to-apex direction along the cochlear ducts of hybrid mutant mice. We have now mapped at least four distinct loci with different strain alleles that differentially modify OHC function in Beethoven mice. Tmc1m1 and potential loci on chromosomes 15 and 17 could collectively account for ∼33% of the observed phenotypic variation in [(C/B)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice, whereas Tmc1m2, Tmc1m3, and Tmc1m4 could account for up to 38% of the variation in [(C/D)F1 × C]N2-Tmc1Bth/+ mice (Table 5). Given the high heritability of the trait, these findings likely reflect the existence of other genetic modifiers with minor effects. Our initial impression of only one or two modifier loci may have been due to inadequate numbers (∼20–40) of N2 progeny in preliminary analyses. Additional modifier loci might be identified using other mouse strains or an intercross mapping strategy, which could also distinguish additive (semidominant) from dominant effects of the alleles. It is also possible that hair cell degeneration itself may be a better quantitative trait to detect and map modifiers. Finally, our strategy requiring selection for Tmc1Bth in N2 mice would be unlikely to detect potential modifier loci linked to Tmc1 on chromosome 19.

Mitochondrial mutations have been implicated in some human auditory neuropathy phenotypes (Ishikawa et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2005) and in modification of age-related hearing loss in mice (Johnson et al. 2001). However, we did not observe an effect of gender on the phenotype of F1 mice or N2 mice, or an effect of parental gender on N2 phenotypes (not shown). These findings indicate there was either no effect or a comparatively minor effect of sex-linked or mitochondrial modifiers in our backcross progeny.

The cochlear locations of OHC loss in Beethoven F1 hybrid mice were consistent with the affected frequencies of hearing and OHC function. ABR thresholds were affected in a high-to-low-frequency gradient (not shown) correlating with the base-to-apex gradient of both IHC and OHC degeneration. Similarly, low-frequency DPOAEs were intact and OHCs were preserved in the apical cochlea, where low-frequency stimuli are transduced. Conversely, the effect of the F1 hybrid background on DPOAE amplitudes was greatest at higher measured f2 frequencies (Figure 4). Because the upper frequency limit of reliable DPOAE measurements in our experiments was 16 kHz (see materials and methods), the capability to accurately measure DPOAEs at f2 ≥ 16 kHz in the future might also reveal diminution of DPOAE amplitudes at these frequencies in the hybrid mutants.

The comparatively modest elevation of ABR thresholds, which is similar in different hybrid Beethoven mice, likely reflects a predominant effect of IHC degeneration and loss of afferent function upon overall hearing. Indeed, we were unable to identify any modifier loci using ABR thresholds as a quantitative trait (not shown). This small effect of genetic background upon hearing thresholds in Beethoven mice is consistent with the uniformity of the DFNA36 phenotype among affected members of a single family (Makishima et al. 2004).

The broad chromosomal intervals of the Tmc1m loci (Figure 6) contain many excellent candidate genes and loci for other auditory disorders, including several implicated in auditory function and hearing loss. For example, the age-related hearing loss locus Ahl2 overlaps with Tmc1m4 on chromosome 5 (Johnson and Zheng 2002). Another example is Tmc2, a closely related paralog of Tmc1 (Kurima et al. 2002, 2003). Tmc2 is expressed in cochlear hair cells and colocalizes with Tmc1m1, but we found no strain-specific coding or splice site sequence variants of Tmc2 correlated with the phenotypic effects of Tmc1m1 (not shown). Similarly, we found no explanatory strain-specific variants of Myo1c (not shown), which colocalizes with Tmc1m2 and has been implicated in hair cell stereocilia function (Holt et al. 2002). Crosses with other strains and interval-specific haplotype analysis could narrow and potentially shift the Tmc1m intervals and our search for causative variants, especially if any of the intervals (Figure 6) are resolved into multiple discrete loci (Dipetrillo et al. 2005).

The microtubule-associated protein gene 1a (Mtap1a) that modifies hearing loss in tubby mice (Ikeda et al. 2002) also colocalizes with Tmc1m1. Although the C57BL/6J variant of Mtap1a is a recessive susceptibility allele for hearing loss in tubby mice (Ikeda et al. 2002), the genotypes and phenotypic effects of C3HeB/FeJ or DBA/2J alleles at this locus have not been reported but warrant future study. Other known modifiers of hearing loss include Cdh23 and Atp2b2 (Noben-Trauth et al. 2003; Schultz et al. 2005), which do not colocalize with any of the Tmc1m loci. We cannot rule out Atp2b2 as a potential modifier since there may not be functionally significant differences in Atp2b2 among the background strains we studied. In contrast, although DBA/2J and C57BL/6J carry the recessive age-related hearing loss (ahl) allele of Cdh23 and C3HeB/FeJ does not (Noben-Trauth et al. 2003), potential modifier loci with recessive DBA/2J or C57BL/6J alleles would not have been detected with our backcross design. Future studies are needed to identify potential interactions of these known modifiers of hearing loss with Tmc1Bth.

We anticipate that identifying the modifiers of Beethoven hair cell degeneration will be difficult, but the potential therapeutic insights offered by genetic modifiers justify a search for them (Nadeau 2005). Since the polygenic modification of OHC degeneration in Beethoven mice is consistent with the presumed complex etiology of OHC degeneration in common SNHL phenotypes in humans, the human orthologs of Beethoven modifiers will be excellent candidates to screen for these complex traits or the phenotypic variation associated with monogenic SNHL in humans (Schultz et al. 2005).

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Friedman and Konrad Noben-Trauth for critical review of the manuscript and Karen Avraham for sharing her observation of strain-dependence of hair cell degeneration in Beethoven mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health intramural research fund Z01-DC-000060-04. Y.N. was supported by research fund 15-KOU-57 from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and Sensory and Communicative Disorders research fund from the Japan Foundation for Aging and Health.

References

- Belyantseva, I. A., E. T. Boger, S. Naz, G. I. Frolenkov, J. R. Sellers et al., 2005. Myosin-XVa is required for tip localization of whirlin and differential elongation of hair-cell stereocilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 7: 148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock, G. R., and K. P. Steel, 1983. Inner ear pathology in the deafness mutant mouse. Acta Otolaryngol. 96: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussoli, T. J., A. Kelly and K. P. Steel, 1997. Localization of the bronx waltzer (bv) deafness gene to mouse chromosome 5. Mamm. Genome 8: 714–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipetrillo, K., X. Wang, I. M. Stylianou and B. Paigen, 2005. Bioinformatics toolbox for narrowing rodent quantitative trait loci. Trends Genet. 21: 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret, G., 1977. Postnatal development in the acoustic system of the house mouse in the light of developing masked thresholds. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 62: 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, T., J. Battey, B. Kachar, S. Riazuddin, K. Noben-Trauth et al., 2000. Modifier genes of hereditary hearing loss. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10: 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, T. B., and A. J. Griffith, 2003. Human nonsyndromic sensorineural deafness. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 4: 341–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolenkov, G. I., I. A. Belyantseva, T. B. Friedman and A. J. Griffith, 2004. Genetic insights into the morphogenesis of inner ear hair cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5: 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, A. J., and T. B. Friedman, 2002. Autosomal and X–Linked Auditory Disorders. Springer, New York.

- Haider, N. B., A. Ikeda, J. K. Naggert and P. M. Nishina, 2002. Genetic modifiers of vision and hearing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11: 1195–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, J. R., S. K. Gillespie, D. W. Provance, K. Shah, K. M. Shokat et al., 2002. A chemical-genetic strategy implicates myosin-1c in adaptation by hair cells. Cell 108: 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner, K. C., M. Lenoir and G. R. Bock, 1985. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions in hearing-impaired mutant mice. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 78: 1603–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, A., Q. Y. Zheng, A. R. Zuberi, K. R. Johnson, J. K. Naggert et al., 2002. Microtubule-associated protein 1A is a modifier of tubby hearing (moth1). Nat. Genet. 30: 401–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, K., Y. Tamagawa, K. Takahashi, H. Kimura, J. Kusakari et al., 2002. Nonsyndromic hearing loss caused by a mitochondrial T7511C mutation. Laryngoscope 112: 1494–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. R., and Q. Y. Zheng, 2002. Ahl2, a second locus affecting age-related hearing loss in mice. Genomics 80: 461–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. R., Q. Y. Zheng, Y. Bykhovskaya, O. Spirina and N. Fischel-Ghodsian, 2001. A nuclear-mitochondrial DNA interaction affecting hearing impairment in mice. Nat. Genet. 27: 191–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T. B., B. Isaacson, T. A. Sivakumaran, A. Starr, B. J. Keats et al., 2004. A gene responsible for autosomal dominant auditory neuropathy (AUNA1) maps to 13q14–21. J. Med. Genet. 41: 872–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurima, K., L. M. Peters, Y. Yang, S. Riazuddin, Z. M. Ahmed et al., 2002. Dominant and recessive deafness caused by mutations of a novel gene, TMC1, required for cochlear hair-cell function. Nat. Genet. 30: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurima, K., Y. Yang, K. Sorber and A. J. Griffith, 2003. Characterization of the transmembrane channel-like (TMC) gene family: functional clues from hearing loss and epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Genomics 82: 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makishima, T., K. Kurima, C. C. Brewer and A. J. Griffith, 2004. Early onset and rapid progression of dominant nonsyndromic DFNA36 hearing loss. Otol. Neurotol. 25: 714–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly, K. F., R. H. Cudmore, Jr. and J. M. Meer, 2001. Map Manager QTX, cross-platform software for genetic mapping. Mamm. Genome 12: 930–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau, J. H., 2005. Listening to genetic background noise. New Engl. J. Med. 352: 1598–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noben-Trauth, K., Q. Y. Zheng and K. R. Johnson, 2003. Association of cadherin 23 with polygenic inheritance and genetic modification of sensorineural hearing loss. Nat. Genet. 35: 21–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ballesteros, M., F. J. del Castillo, Y. Martin, M. A. Moreno-Pelayo, C. Morera et al., 2003. Auditory neuropathy in patients carrying mutations in the otoferlin gene (OTOF). Hum. Mutat. 22: 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrott, A., J. L. Puel and G. Rebillard, 1991. Cochlear origin of 2f1-f2 distortion products assessed by using 2 types of mutant mice. Hear. Res. 52: 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, J. M., Y. Yang, A. J. Caride, A. G. Filoteo, A. R. Penheiter et al., 2005. Modification of human hearing loss by plasma-membrane calcium pump PMCA2. New Engl. J. Med. 352: 1557–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, A., T. W. Picton, Y. Sininger, L. J. Hood and C. I. Berlin, 1996. Auditory neuropathy. Brain 119(Pt 3): 741–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymko-Bennett, Y. M., K. Kurima, B. Olsen, R. Seegmiller and A. J. Griffith, 2003. Auditory function associated with Col11a1 haploinsufficiency in chondrodysplasia (cho) mice. Hear. Res. 175: 178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga, R., P. M. Kelley, B. J. Keats, A. Starr, S. M. Leal et al., 2003. Non-syndromic recessive auditory neuropathy is the result of mutations in the otoferlin (OTOF) gene. J. Med. Genet. 40: 45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viberg, A., and B. Canlon, 2004. The guide to plotting a cochleogram. Hear. Res. 197: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreugde, S., A. Erven, C. J. Kros, W. Marcotti, H. Fuchs et al., 2002. Beethoven, a mouse model for dominant, progressive hearing loss DFNA36. Nat. Genet. 30: 257–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q., R. Li, H. Zhao, J. L. Peters, Q. Liu et al., 2005. Clinical and molecular characterization of a Chinese patient with auditory neuropathy associated with mitochondrial 12S rRNA T1095C mutation. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 133: 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]