Abstract

We examined the effects of several E-ring and F-ring isoprostanes on mechanical activity in pulmonary artery and vein.

8-iso PGE2 and 8-iso PGF2α were powerful spasmogens in human vasculature and in canine pulmonary vein. 8-iso PGE1 and 8-iso PGF2β also exhibited moderate spasmogenic activity in canine pulmonary vein; 8-iso PGF1α, 8-iso PGF1β, and 8-iso PGF3α were generally ineffective. Canine pulmonary arteries did not exhibit excitatory responses to any of the isoprostanes.

The spasmogenic effects of 8-iso PGE2 were markedly attenuated by the TP-receptor blocker ICI 192605 and by the EP-receptor blocker AH 6809 (−log KB=8.4 and 5.7, respectively). PGE2 was a very weak agonist (≈100 fold less so than 8-iso PGE2).

In the presence of ICI 192605 (10−6 M), 8-iso PGE1 evoked modest dose-dependent relaxations in human and canine pulmonary vein, and in canine pulmonary artery, but not in the human pulmonary artery. The other isoprostanes were generally ineffective as vasodilators in the pulmonary vasculature of both species.

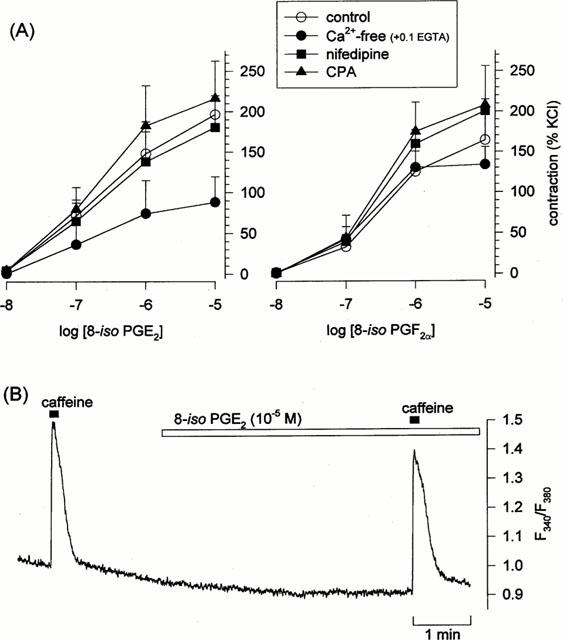

The spasmogenic effects of 8-iso PGE2 and 8-iso PGF2α did not involve elevation of [Ca2+]i.

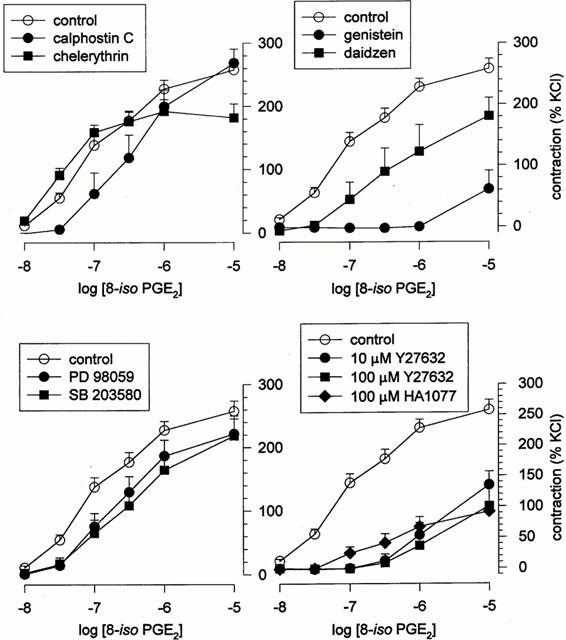

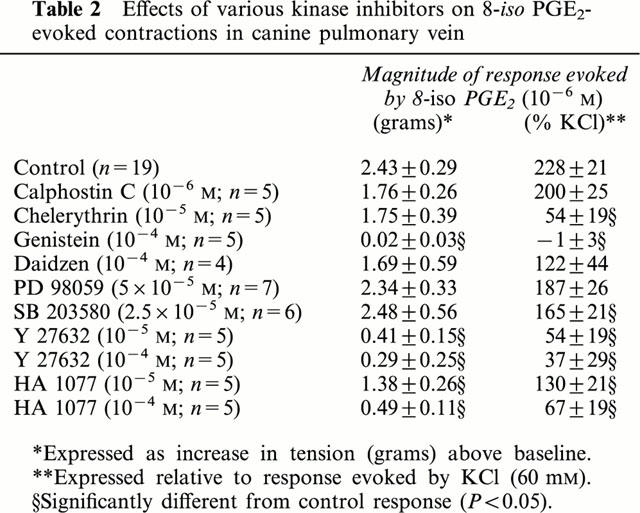

8-iso PGE2-evoked contractions were blocked by inhibitors of tyrosine kinase (genistein) and Rho kinase (Y 27632 and HA 1077), but not by inhibitors of protein kinase C (calphostin C or chelerythrine), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (PD 98059) or p38-kinase (SB 203580).

The actions of 8-isoprostanes in the lungs are compound-, species- and tissue-dependent. Several isoprostanes evoke vasoconstriction: in the case of 8-iso PGE2, this involves activation of TP-receptors, tyrosine kinases and Rho kinases. 8-iso PGE1 is also able to cause vasodilation.

Keywords: Pulmonary artery, pulmonary vein, vascular smooth muscle, contraction, isoprostanes, relaxation, prostanoid receptors, tyrosine kinase, MAP kinase

Introduction

The pulmonary arteries and veins are continually exposed to free radicals and reactive oxygen species originating from inspired air and/or from inflammatory cells (in the blood or resident in the airway wall). Recently, it has been found that pulmonary vascular tone is dramatically altered by reactive oxygen species such as peroxide and superoxide, and that several signalling pathways might be involved. For example, H2O2 constricts rat pulmonary artery via activation of tyrosine kinases (Jin & Rhoades, 1997), and rabbit pulmonary artery via activation of serine esterases and/or phospholipase C (Sheehan et al., 1993). In bovine pulmonary artery, however, H2O2 evokes vasodilation via activation of guanylate cyclase (Burke & Wolin, 1987).

It is now recognized that peroxide and superoxide can oxidize arachidonic acid in the plasmalemma in a non-enzymatic fashion, giving rise to a class of compounds known as isoprostanes (Morrow et al., 1990). Isoprostanes differ structurally from prostaglandins by the cis-orientation at the cyclopentane ring junction compared to the trans-orientation in the classical prostanoids. Thus, plasma and urinary levels of 8-isoprostanes are markedly elevated in many conditions characterized by oxidative stress, including asthma (Montuschi et al., 1999a), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Praticò et al., 1998b), interstitial lung disease (Montuschi et al., 1998), cystic fibrosis (Montuschi et al., 1999b), or acute chest syndrome (Klings et al., 1999); they are also increased in healthy volunteers exposed to cigarette smoke (Chiabrando et al., 1999; Delanty et al., 1996; Morrow et al., 1995; Praticò et al., 1998a; Reilly et al., 1996), allergen (Dworski et al., 1999), ozone (Hazbun et al., 1993) or hyperoxia (Vacchiano & Tempel, 1994).

Despite their prevalence in these disease states, the biological effects of 8-isoprostanes in smooth muscle are very poorly understood. Most previous studies describe the effects of only one particular isoprostane (8-iso-PGF2α) in smooth muscle tissues from one species (rat), finding it to be a potent vasoconstrictor which appears to act through prostanoid TP receptors (Kang et al., 1993; John & Valentin, 1997). One other group also described a vasodilatory effect of 8-iso-PGF2α (Jourdan et al., 1997). However, a great deal of work remains to be done, since: (1) dozens of isoprostanes exist whose effects have not yet been studied; (2) most of the studies which have been done have used rat smooth muscles, and none have used human pulmonary vasculature; (3) the intracellular signalling pathways through which isoprostanes act are entirely unclear. Consequently, we set out to address each of these three deficiencies by investigating the effects of a series of isoprostanes in human and canine pulmonary vasculature.

Methods

Preparation of tissues

Peripheral portions of human lungs were obtained which had been resected at a local hospital (St. Joseph's Hospital, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) and judged by the pathologist to be macroscopically normal (n=28); prior approval has been obtained for use of such tissues in our research. Pairs of blood-containing and air-containing vessels (outer diameter 0.5 to 2 mm) wrapped together within a connective tissue sheath (the tunica media) were presumed to be small order pulmonary artery and bronchial airway, respectively; blood-containing vessels which were not closely associated with an airway were presumed to be pulmonary vein. These small order arteries and veins were carefully removed and cut into ring segments ≈4 – 5 mm long; no attempt was made to remove the endothelium.

Adult mongrel dogs were euthanized with pentobarbitone sodium (100 mg kg−1), after which lung lobes were excised and kept in physiological solution. After removing the overlying parenchyma and connective tissue, the pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein were excised and cut into ring segments ≈4 – 5 mm long (O.D.≈2 – 10 mm); no attempt was made to remove the endothelium.

Organ bath studies

Ring segments of smooth muscle were mounted vertically in organ baths using silk (Ethicon 4.0) tied to either end of the strip; one end was fastened to a Grass FT03 force transducer while the other was anchored. Isometric changes in tension were digitized and recorded using an on-line program (DigiMed System Integrator, MicroMed, Louisville, KY, U.S.A.). Tissues were bathed in Krebs-Ringer's buffer (see below for composition) containing indomethacin (10 μM), bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2, and maintained at 37°C, with a preload tension of ≈1.25 g. Tissues were first equilibrated for 1 – 2 h; where indicated, some tissues were challenged with 60 mM KCl for use later in standardizing the excitatory responses to the isoprostanes. After wash-out of KCl and recovery of the tissues, the specific experiments were commenced.

Fura-2 fluorimetry

Ring segments (0.5 – 1.0 g wet weight) of pulmonary vasculature were minced and transferred to dissociation buffer (composition given below) containing collagenase (type IV; 2.7 u ml−1), elastase (type IV; 12.5 u ml−1), and BSA (1 mg ml−1), then were either used immediately or stored at 4°C for use the next day; we have previously found that cells used immediately and those used after refrigeration exhibit similar functional responses. To liberate single cells, tissues in enzyme-containing solution were incubated at 37°C for 40 – 60 min, then gently triturated. Cells were studied using a filter-based photometer-driven system (DeltaScan; Photon Technology International, Inc., South Brunswick, NJ, U.S.A.). After settling onto a glass coverslip mounted onto a Nikon TMD inverted microscope, cells were loaded with the membrane-permeant form of fura-2 (fura-2/AM, 2 μM for 30 min at 37°C), then superfused continuously with Ringers buffer (2 – 3 ml min−1). Cells were illuminated alternately (0.5 Hz) at the excitation wavelengths and the emitted fluorescence (measured at 510 nm) induced by 340 nm excitation (F340) and that induced by 380 nm excitation (F380) was measured using a photomultiplier tube assembly. Agonists were applied by pressure ejection from a puffer pipette (Picospritzer II; General Valve Corp., Fairfield, NJ, U.S.A.).

Solutions and chemicals

Dissociation buffer contained (in mM): NaCl, 125; KCl, 5; CaCl2, 1; MgCl2, 1; HEPES, 10; EDTA, 0.25; D-glucose, 10; L-taurine, 10; pH 7.0. Single cells were studied in Ringer's buffer containing (in mM): NaCl, 130; KCl, 5; CaCl2, 1; MgCl2, 1; HEPES, 20; D-glucose, 10; pH 7.4. Intact tissues were studied using Krebs-Ringer's buffer containing (in mM): NaCl, 116; KCl, 4.2; CaCl2, 2.5; NaH2PO4, 1.6; MgSO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 22; D-glucose, 11; bubbled to maintain pH at 7.4. Indomethacin (10 μM) was also added to the latter to prevent generation of cyclo-oxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid.

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company, with the exception of the isoprostanes (Cayman Chemical Company; Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.) and Y 27632 (kindly provided by A. Yoshimura, Welfide Corporation, Osaka, Japan). All isoprostanes were dissolved initially in ethanol except for 8-iso PGF3α (methyl acetate); these stock solutions can be stored for several months at −10°C. Cyclopiazonic acid, calphostin C, chelerythrin, genistein, daidzen, PD 98059, SB 203580, ICI 192605 and AH 6809 were dissolved in DMSO; nifedipine and Y27632 were dissolved in ethanol. These 10 mM stock solutions were then diluted using Krebs-Ringer's buffer to the concentrations indicated in the text; the final bath concentration of solvent did not exceed 0.1%, which was found to have no effect on mechanical activity. All other pharmacological agents used were made up as aqueous solutions. Calphostin C was photoactivated using a fluorescent lamp (12 W) placed approximately 15 cm from the baths for 5 min. Each tissue was exposed to only one isoprostane (and in some cases to one antagonist), then discarded.

Data analysis

Contractile responses to isoprostanes in canine vasculature were standardized as a per cent of the response to 60 mM KCl. The human vascular tissues, on the other hand, sometimes exhibited little or no response to KCl yet substantial responses to the isoprostanes (e.g., see Figure 1); thus, the responses in human vascular tissues were expressed as grams tension generated. Relaxations were expressed as a per cent reversal of the adrenergic tone existing before addition of isoprostane.

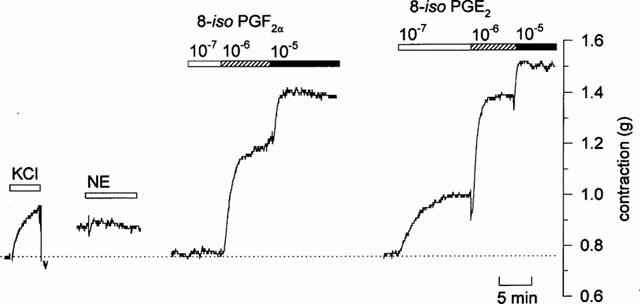

Figure 1.

Original tracing showing mechanical responses in human pulmonary artery with outer diameter of less than 1 mm. This tissue exhibited a relatively small response to KCl (30 mM), and essentially no response 90 min later when challenged with norepinephrine (10−6 M). However, substantial contractions were evoked in this tissue 30 min later following challenge with 8-iso PGF2α (10−7 to 10−5 M); after wash-out and another 45 min for recovery, even larger responses were evoked by 8-iso PGE2 (10−7 to 10−5 M).

The maximal contraction (Emax) produced with the highest concentration and the half-maximum effective concentration (EC50) for the isoprostanes were interpolated from the individual concentration-effect curves. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KB) for a given antagonist was calculated using the equation: KB=[B]/(DR-1), where [B] is the concentration of the antagonist and DR (dose ratio) is the ratio of EC50 in the presence and absence of antagonist.

Data are reported as mean±s.e. mean, and compared using a paired Students' t-test, with P values <0.05 being considered significant.

Results

Contractile responses to isoprostanes

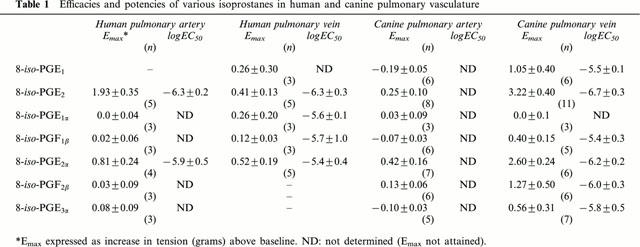

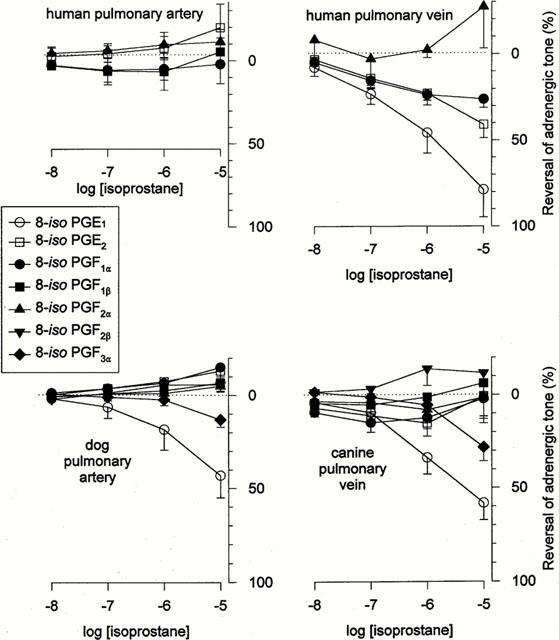

In human pulmonary artery and vein, the isoprostanes 8-iso PGE2 and 8-iso PGF2α evoked large, sustained and dose-dependent contractions, even in tissues which exhibited little or no response to KCl (60 mM), phenylephrine (10−5 M) or norepinephrine (10−6 M) (e.g., Figure 1). 8-iso PGE2 was significantly more efficacious than 8-iso PGF2α in the human pulmonary artery (although equipotent; Table 1), while the two were equally potent and effective in the human pulmonary vein (Table 1). The other isoprostanes tested – 8-iso PGE1, 8-iso PGF1α, 8-iso PGF1β, 8-iso PGF2β and 8-iso PGF3α – had little or no excitatory effect on the human vasculature (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Efficacies and potencies of various isoprostanes in human and canine pulmonary vasculature

Figure 2.

Spasmogenic effects of 8-isoprostanes. Mean dose-contraction relationships obtained in pulmonary artery (left panels) and pulmonary vein (right panels) of the human (top) and dog (bottom), as indicated. Data indicate means±s.e.mean (values for n given in Table 1).

Canine pulmonary vasculature, on the other hand, displayed a markedly different profile of responsiveness to these isoprostanes. The pulmonary artery was essentially unresponsive to any of the isoprostanes, while the pulmonary vein exhibited an excitatory response to both E-ring isoprostanes as well as 8-iso PGF2α and 8-iso PGF2β, with 8-iso PGE2 and 8-iso PGF2α being the most potent and efficacious. The mean concentration-response relationships for the isoprostanes in both tissues are summarized in Figure 2, and EC50 values given in Table 1.

Sensitivity of excitatory responses to prostanoid receptor blockers

In many other smooth muscle preparations, excitatory responses evoked by isoprostanes are sensitive to a variety of TP-receptor antagonists (Kang et al., 1993; Kawikova et al., 1996; Okazawa et al., 1997); one other report provided evidence that they might act through EP-receptors (Elmhurst et al., 1997). We therefore tested the effects of the TP receptor blocker ICI 192605 (10−6 M) and the DP/EP receptor blocker AH 6809 (50 μM) on isoprostane-mediated contractions in canine pulmonary vein. Tissues were preexposed to these blockers for 20 – 30 min before re-examining the dose-contraction relationship for 8-iso PGE2 (the most potent isoprostane).

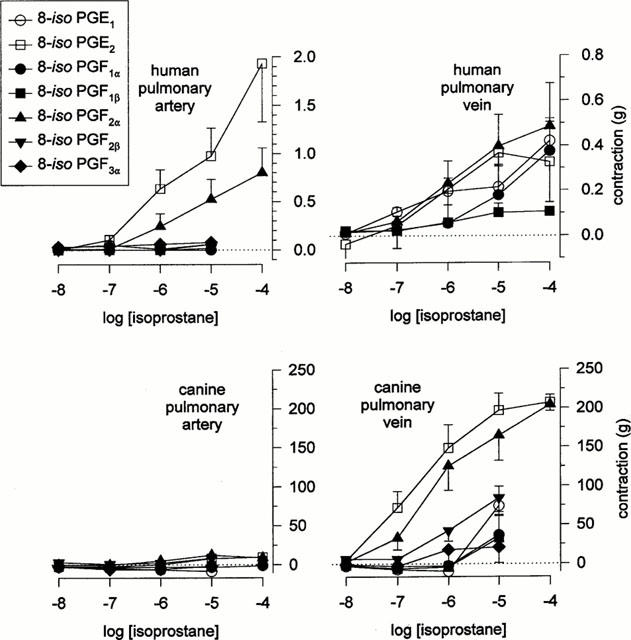

ICI 192605 markedly suppressed 8-iso PGE2-evoked contractions, displacing the 8-iso PGE2 dose-response relationship one full log unit when used at 10−8 M (Figure 3A); KB was determined to be 3.7×10−9 M (−log KB=8.4). 8-iso PGE2-contractions were nearly abolished by 10−7 ICI 192605; thus, it was not possible to determine a value for KB using these data.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological characterization of excitatory receptors through which isoprostanes act. Mean dose-response relationship for 8-iso PGE2 in canine pulmonary vein, obtained in the presence and absence of the TP-receptor blocker ICI 192605 (A; n=5) or the EP-receptor blocker AH 6809 (B; n=5). For comparison, the mean dose-response relationship for prostaglandin E2 in the presence and absence of AH 6809 are also given in B (n=4).

Prostaglandin E2 evoked dose-dependent contractions (Figure 3B); however, the concentrations required were ≈100 fold higher than those at which 8-iso PGE2 is effective, arguing against the possibility that 8-iso PGE2 is acting through EP-receptors. These PGE2-evoked contractions were markedly suppressed by AH 6809 (Figure 3B); it was not possible to ascertain values for KB from these data. The 8-iso PGE2 dose-response relationship was also sensitive to AH 6809, being displaced ≈0.5 and ≈1 log units by 5×10−6 and 5×10−5 M AH-6809, respectively (Figure 3B), yielding values for KB of 1.4×10−6 and 2.1×10−6 M, respectively.

Relaxant responses to isoprostanes in pulmonary vasculature

We also sought to determine if pulmonary vascular tissues might exhibit vasodilation in response to isoprostanes, as has been shown in rat pulmonary artery (Jourdan et al., 1997) and human airway smooth muscle (Janssen et al., 2000). Tissues were preconstricted with phenylephrine (3×10−5 M) in the presence of ICI 192605 (10−6 M; to block the excitatory effects of the isoprostanes described above).

The human pulmonary arterial segments did not exhibit vasodilatory responses to any of the isoprostanes tested, while human pulmonary vein relaxed in response to 8-iso PGE1, and much less so in response to 8-iso PGE2, and 8-iso PGF1α (Figure 4). The canine pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein were both essentially unresponsive to any of the isoprostanes except 8-iso PGE1, which caused ≈50% reversal of adrenergic tone (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Vasodilatory effects of 8-isoprostanes. Human (top) and canine (bottom) pulmonary arterial and venous tissues (left and right panels, respectively) were preconstricted with phenylephrine (3×10−5 M) in the presence of ICI 192605 (10−6 M; to prevent isoprostane-induced vasoconstriction), after which increasing doses of isoprostanes were added in cumulative fashion. Data indicate means±s.e.mean (n=4 – 7 for canine data; n=3 – 5 for human data).

Role of Ca2+ in mediating isoprostane-contractions

Contraction in smooth muscle is ultimately dependent on Ca2+, and spasmogens can act either by mobilizing Ca2+ (triggering influx of external Ca2+ or release of internal Ca2+) and/or by increasing the sensitivity of the contractile apparatus to cytosolic [Ca2+]i (Somlyo & Somlyo, 2000). We therefore examined the role(s) of Ca2+ in mediating isoprostane responses in canine pulmonary vein by preventing Ca2+-influx using nominally Ca2+-free media (supplemented with 0.1 mM EGTA to chelate trace Ca2+) or using nifedipine (10−6 M), and by depleting the internal Ca2+ pool using cyclopiazonic acid (3×10−5 M). Neither nifedipine nor cyclopiazonic acid had any effect on the dose-response relationship for 8-iso PGE2 nor 8-iso PGF2α (Figure 5A). Likewise, omission of external Ca2+ had no effect on the responses to 8-iso PGF2α, and only partially reduced the responses to 8-iso PGE2 (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Role of Ca2+ in isoprostane-evoked contractions. (A) Effects of nifedipine, cyclopiazonic acid, or nominally Ca2+-free media (supplemented with 0.1 mM EGTA) on the mean dose-response relationship for 8-iso PGF2 (left) or 8-iso PGF2α (right) in canine pulmonary vein. Data indicate means±s.e.mean (n=5). (B) Original recording from a single human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell loaded with the Ca2+-indicator dye fura-2 : 8-iso PGE2 (10−5 M) had no effect on F340/F380, although the cell exhibited normal responsiveness to caffeine (10 mM).

We also examined directly the ability of isoprostanes to mobilize Ca2+ in single cells loaded with the Ca2+-indicator dye fura-2. None of the canine pulmonary vein cells exhibited a change in [Ca2+]i in response to either 8-iso PGE2 (16 cells; n=7) or 8-iso PGF2α (7 cells; n=5), even though all of these cells exhibited a substantial response to caffeine. Qualitatively similar observations were made in human pulmonary artery cells (Figure 5B): 8-iso PGE2 had no effect in three of four cells (n=2) which exhibited large responses to caffeine (evoking a small elevation in the fourth cell), and 8-iso PGF2α evoked no change in four caffeine-responsive cells tested (n=2).

Role of kinases in mediating isoprostane-contractions

Finally, we examined the possibility that isoprostanes act by increasing the sensitivity of the contractile apparatus to [Ca2+]i; this mechanism has been shown elsewhere to involve protein kinase C, tyrosine kinases, and/or mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (Somlyo & Somlyo, 2000). Tissues were exposed to various kinase blockers for 20 – 30 min before the 8-iso PGE2 dose-response relationship was examined.

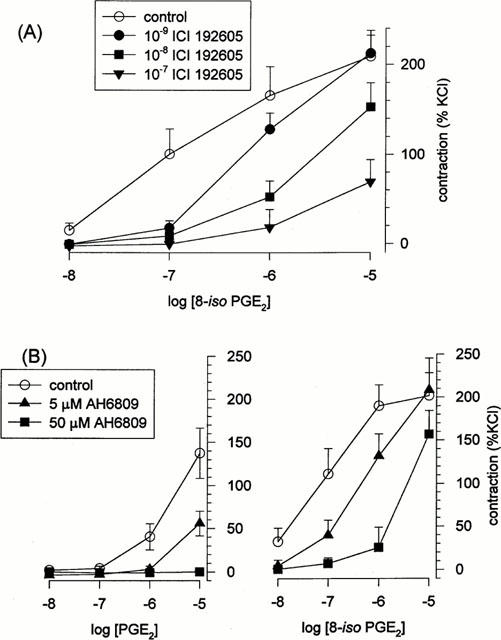

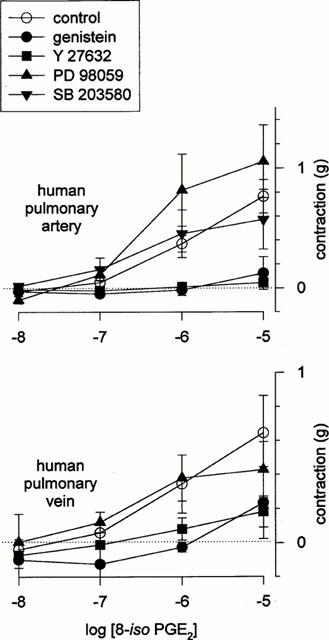

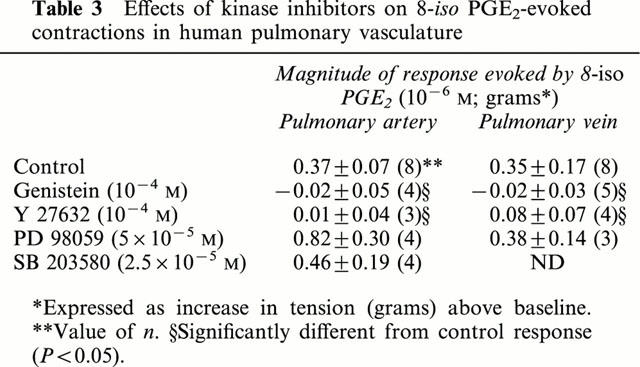

In the canine pulmonary vein, contractions to 8-iso PGE2 were unaffected by the protein kinase C inhibitors calphostin C (10−6 M) or chelerythrine (10−6 M) (Figure 6; Table 2), but were essentially abolished by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (10−6 M) (Figure 6; Table 2). Daidzen (10−6 M), the less active analogue of genistein, produced only marginal suppression of 8-iso PGE2-contractions (Figure 6; Table 2). Tyrosine kinases trigger contraction in smooth muscle via activation of one or more MAP kinases. We found the inhibitory effect of genistein on responses to 8-iso PGE2 was mimicked by the Rho kinase inhibitors Y 27632 and HA 1077 (10−5 and 10−4 M; Figure 6; Table 2) but not by inhibitors of MAP kinase kinase (PD 98059; 5×10−5 M) or of p38-kinase (SB 203580; 2.5×10−5 M) (Figure 6; Table 2). Similar findings were obtained when human pulmonary artery and vein were used (Figure 7; Table 3).

Figure 6.

Role of protein kinases in isoprostane-evoked contractions. Mean dose-response relationship for 8-iso PGE2 in canine pulmonary vein, obtained in the presence and absence of: (top left) the protein kinase C inhibitors calphostin C (10−6 M) or chelerythrine (10−6 M); (top right) the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (10−4 M), and its less active analogue daidzen (10−4 M); (bottom left) the MAP kinase kinase inhibitor PD 98059 (5×10−5 M) or the p38-kinase inhibitor SB 203580 (2.5×10−5 M); (bottom right) the Rho-kinase inhibitors Y 27632 (10−5 or 10−4 M) or HA 1077 (10−4 M). Data indicate means±s.e.mean (n values given in Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of various kinase inhibitors on 8-iso PGE2-evoked contractions in canine pulmonary vein

Figure 7.

Effect of kinase blockers on 8-iso PGE2-contractions in human vasculature. Mean dose-response relationship for 8-iso PGE2 in human pulmonary vasculature, obtained in the presence and absence of genistein (10−4 M), Y 27632 (10−4 M), calphostin C (10−6 M), PD 98059 (5×10−5 M) or SB 203580 (2.5×10−5 M). Data indicate means±s.e.m (n=3 – 5).

Table 3.

Effects of kinase inhibitors on 8-iso PGE2-evoked contractions in human pulmonary vasculature

Discussion

There have been some reports in the past of isoprostane-mediated contractions in smooth muscle, including a few using pulmonary artery from rodents (Kang et al., 1993; John & Valentin 1997; Jourdan et al., 1997), but none using human pulmonary artery or vein. It is important to also point out that many previous studies used main branch segments of vasculature, not smaller resistance vessels. Furthermore, previous studies of the effects of isoprostanes in smooth muscle in general have been very limited in that the excitatory effects of only one isoprostane (8-iso PGF2α) were examined (although there are dozens or hundreds of others), and that the signalling pathways underlying these responses were not elucidated. In this study, we examined the effects of several different E-ring and F-ring isoprostanes on human and canine pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein, and the roles of Ca2+, protein kinase C, tyrosine kinases, and MAP kinases in mediating these responses.

We describe here for the first time the effects on human pulmonary artery and vein (outer diameter of 0.5 – 2 mm) of a wide range of E-ring and F-ring isoprostanes, finding these to mediate both powerful excitatory and modest inhibitory effects. These responses were isoprostane-specific and species-dependent. Human pulmonary artery and vein, as well as canine pulmonary vein, exhibited substantial contractions to several isoprostanes (8-iso PGE2 and 8-iso PGF2α in particular), while canine pulmonary artery did not. It is worth pointing out that 8-iso PGE2 was considerably more potent and efficacious than 8-iso PGF2α, the isoprostane previously studied most frequently. On the other hand, vasodilation was evoked by 8-iso PGE1 in the pulmonary vein of both species and in canine pulmonary artery, but not human pulmonary artery. The knowledge that the isoprostanes are relatively ineffective as vasodilators is valuable in interpreting the excitatory responses to these agents: it rules out the possibility that the contractile responses are partially or wholly masked by a simultaneous inhibitory effect by the isoprostane(s) studied.

As in our earlier study of the effect of isoprostanes on airway smooth muscle, we were struck by the marked differences in responses to isoprostanes with nearly identical structure. For example, 8-iso PGF2α is a powerful spasmogen in human pulmonary vasculature, while 8-iso PGF1α and 8-iso PGF3α (which differ only in having one less or one more double bond, respectively) are not. On the other hand, 8-iso PGE2 is a very potent spasmogen and ineffective as a vasodilator, while the complete opposite is true of 8-iso PGE1. These stark differences in structure-activity relationships indicate their involvement through very specific receptors, rather than some non-specific change such as altered membrane fluidity.

Receptors mediating isoprostane-responses

We examined the type/subtype of receptor(s) through which the responses to the most potent and powerful isoprostane (8-iso PGE2) are mediated. Previous studies have shown that contractions triggered by isoprostanes are sensitive to a wide variety of agents which are structurally distinct but which all exhibit TP-receptor blocking activity (Kang et al., 1993; Kawikova et al., 1996; Okazawa et al., 1997), suggesting that they are mediated through TP-receptors; there is evidence that EP-receptors may also be involved (Elmhurst et al., 1997). Excitatory prostanoid receptors in human pulmonary vasculature include TP-and EP3-receptors (Qian et al., 1994). Consistent with this, we found the responses in both human and canine pulmonary vasculature to be highly sensitive to the TP-receptor antagonist ICI 192605, and the −log KB value which we derived was comparable to those published elsewhere (Coleman et al., 1994). The DP/EP-receptor antagonist AH 6809 was also able to displace 8-iso PGE2 in an apparently competitive fashion, and the −log KB values of 5.9 and 5.7 which we obtained were also comparable to published values of 6.4 – 7.0 (Coleman et al., 1994) and 5.8 (Norel et al., 1999). However, we find it difficult to interpret this to mean that 8-iso PGE2 acts through EP-receptors in the canine pulmonary vein, since the non-specific EP-agonist PGE2 was very ineffective (100 times less potent than 8-iso PGE2), suggesting that this tissue is in fact poorly endowed with EP receptors. It may be, then, that AH 6809 can exert some degree of inhibition of TP-receptors.

In addition to their spasmogenic properties, we uncovered some inhibitory effects of the isoprostanes: 8-iso PGE1 (but not the other isoprostanes tested) partially reversed adrenergic tone in canine pulmonary artery, as well as the pulmonary vein of both species. The relative inability of isoprostanes to evoke relaxation in pulmonary vasculature is in marked contrast to airway smooth muscle, in which we found several isoprostanes, particularly 8-iso PGE1 and 8-iso PGE2, to be capable of completely reversing cholinergic tone at relatively low concentrations (10−2 to 10−6 M) (Janssen et al., 2000). The receptors through which these inhibitory effects are mediated are as yet unclear. Walch et al., (1999) have characterized the prostanoid receptors mediating dilation of the human pulmonary vasculature, finding them to include DP-, IP-, and some EP-receptors in the pulmonary veins, but only IP-receptors in the pulmonary arteries.

We made no attempt in this study to ascertain whether the receptor(s) which are activated by the isoprostanes are located on the smooth muscle and/or on the endothelium, nor whether the responses involve generation of some other factor from the endothelium.

Signalling pathways

We also examined the signalling pathways underlying the excitatory responses to 8-iso PGE2. These appear not to be critically dependent upon Ca2+ mobilization, since they were unaffected by blocking Ca2+-influx using nifedipine or depleting the internal Ca2+ pool using cyclopiazonic acid. Moreover, direct measurements of [Ca2+]i in single cells showed they did not elevate [Ca2+]i, even though the cells were still able to respond in this way to caffeine or phenylephrine. These findings suggest that 8-iso PGE2 does not act by elevating [Ca2+]i.

Instead, 8-iso PGE2 may act by increasing the [Ca2+]i-sensitivity of the contractile apparatus; others have shown that Ca2+-sensitization in smooth muscle involves suppression of myosin light chain phosphatase activity by Rho kinase and net accumulation of phosphorylated myosin light chain (Somlyo & Somlyo, 2000). We found that two agents which are selective blockers of protein kinase C – but with differing mechanisms of action (chelerythrin interacts with the catalytic domain of protein kinase C, while calphostin C interacts with its regulatory domain) – had little or no effect on the responses, clearly ruling out a role for protein kinase C. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein, however, essentially abolished these responses, while daidzen (a structural analogue of genistein, but lacking most of the tyrosine kinase blocking activity) did not, strongly suggesting that tyrosine kinases are involved. Tyrosine kinases are known to activate several other kinases. We found that the inhibitory effect of genistein was mimicked by two structurally distinct agents which are both putatively highly selective for Rho-kinase, but was not mimicked at all by PD 98059 (putatively specific inhibitor of MAP kinase kinase, which activates ERK1/ERK2) or by SB 203580 (putatively highly specific inhibitor of p38-kinase).

Our observation that 8-iso PGE2-contractions were partially reduced by chelation of external Ca2+ is not inconsistent with the mechanism we promote above. While an increase in the Ca2+-sensitivity of the contractile apparatus permits contraction to occur at levels of [Ca2+]i which are otherwise sub-threshold, it is still possible to reduce [Ca2+]i sufficiently that contractions are eventually impaired (as can happen using high concentrations of a Ca2+ chelator). It is important to distinguish between contractions which are not dependent on Ca2+-mobilization from those which are truly ‘Ca2+-independent'.

Conclusion

We have examined the effects of several different isoprostanes on human and canine pulmonary artery and vein, finding them to be highly biologically active, evoking contractions and/or relaxations in a species-, tissue-, and compound-specific fashion. In our experience, 8-iso PGE2 is the most potent, more so than the isoprostane most commonly studied previously (8-iso PGF2α). The excitatory effects of 8-iso PGE2 are mediated through a TP receptor coupled to tyrosine kinase(s) and Rho-kinase, but not through mobilization of Ca2+. Instead, they would seem to increase the sensitivity of the contractile apparatus to Ca2+ such that even basal levels of [Ca2+]i are sufficient to produce contraction.

Abbreviations

- AH 6809

6-isopropoxy-9-oxoxanthene-2-carboxylic acid

- [Ca2+]i

cytosolic concentration of Ca2+

- CPA

cyclopiazonic acid

- EC50

half-maximally effective concentration

- HA 1077

1-(5-isoquinolinylsulphonyl)-homopiperazine

- ICI 192605

4(Z)-6-[(2,4,5 cis)2-(2-chlorophenyl)-4-(2-hydroxy phenyl)1,3-dioxan-5-yl]hexenoic acid

- MAP kinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- O.D.

outer diameter

- PASM

pulmonary arterial smooth muscle

- PD 98059

2-2(2′-amino-3′-methoxyphenol)-oxanapthalene-4-one

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- PVSM

pulmonary venous smooth muscle

- SB 203580

4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulphinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole

- SM

smooth muscle

- Y27632

(+)-(R)-trans-4-(1-aminoethyl)-N-(pyridyl) cyclohexanecarboxamide dihydrochloride

References

- BURKE T.M., WOLIN M.S. Hydrogen peroxide elicits pulmonary arterial relaxation and guanylated cyclase activation. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;252:H721–H732. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.4.H721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIABRANDO C., VALAGUSSA A., RIVALTA C., DURAND T., GUY A., ZUCCATO E., VILLA P., ROSSI J.C., FANELLI R. Identification and measurement of endogenous beta-oxidation metabolites of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1313–1319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., SMITH W.L., NARUMIYA S. VIII International union of pharmacology classification of prostanoid receptors: properties, distribution, and structure of receptors and their subtypes. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELANTY N., REILLY M., PRATICÒ D., FITZGERALD D.J., LAWSON J.A., FITZGERALD G.A. 8-Epi PGF2α: specific analysis of an isoeicosanoid as an index of oxidant stress in vivo. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996;42:15–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.03804.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DWORSKI R., FISHER L., MURRAY J.J., ROBERTS L.J., OATES J.A., SHELLER J.R. Allergen-induced increase in urinary and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) F-isoprotanes (IsoPs), 8-epi-PGF2α in atopic asthmatics. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1999;159:A96. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9903064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELMHURST J.L., BETTI P.A., RANGACHARI P.K. Intestinal effects of isoprostanes: evidence for the involvement of prostanoid EP and TP receptors. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 1997;282:1198–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAZBUN M.E., HAMILTON R., HOLIAN A., ESCHENBACHER W.L. Ozone-induced increases in substance P and 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α in the airways of human subjects. Am. J. Resp. Cell Mol. Biol. 1993;9:568–572. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/9.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSSEN L.J., PREMJI M., NETHERTON S., CATALLI A., COX P., KESHAVJEE S., CRANKSHAW D.J. Excitatory and inhibitory actions of isoprostanes in human and canine airway smooth muscle. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:506–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN H., RHOADES R.A. Activation of tyrosine kinases in H2O2-induced contraction in pulmonary artery. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:H2686–H2692. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHN G.W., VALENTIN J.P. Analysis of the pulmonary hypertensive effects of the isoprostane derivative, 8-iso-PGF2alpha, in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:899–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOURDAN K.B., EVANS T.W., CURZEN N.P., MITCHELL J.A. Evidence for a dilator function of 8-iso prostaglandin F2 alpha in rat pulmonary artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:1280–1285. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANG K.H., MORROW J.D., ROBERTS L.J., NEWMAN J.H., BANERJEE M. Airway and vascular effects of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α in isolated perfused rat lung. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;74:460–465. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.1.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWIKOVA I., BARNES P.J., TAKAHASHI T., TADJKARIMI S., YACOUB M.H., BELVISI M.G. 8-Epi-PGF2α, a novel noncyclooxygenase-derived prostaglandin, constricts airways in vitro. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1996;153:590–596. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINGS E.S., CHRISTMAN B., HEALY A.M., FARBER H.W. Increased oxidant stress and altered nitric oxide metabolism in acute chest syndrome of sickle cell disease. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1999;159:A568. [Google Scholar]

- MONTUSCHI P., CIABATTONI G., CORRADI M., NIGHTINGALE J., COLLINS J.V., KHARITONOV S.A., BARNES P.J. 8-Isoprostane, a new biomarker of oxidative stress in asthma. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1999a;159:A97. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9809140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTUSCHI P., CIABATTONI G., PAREDI P., PANTELIDIS P., DU BOIS R.M., KHARITONOV S.A., BARNES P.J. 8-Isoprostane as a biomarker of oxidative stress in interstitial lung diseases. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1998;158:1524–1527. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9803102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTUSCHI P., PAREDI P., CORRADI M., CIABATTONI G., HODSON M.I., KHARITONOV S.A., BARNES P.J. 8-Isoprostane, a biomarker of oxidative stress, is increased in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1999b;159:A271. [Google Scholar]

- MORROW J.K., HILL K.E., BURK R.F., NAMMOUR T.M., BADR K.F., ROBERTS L.J. A series of prostaglandin F2-like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:9383–9387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORROW J.D., FREI B., LONGMIRE A.W., GAZIANO J.M., LYNCH S.M., SHYR Y., STRAUSS W.E., OATES J.A., ROBERTS L.J. Increase in circulating products of lipid peroxidation (F2-sioprostanes) in smokers. New Eng. J. Med. 1995;332:1198–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOREL X., WALCH L., LABAT C., GASCARD J.-P., DULMET E., BRINK C. Prostanoid receptors involved in the relaxation of human bronchial preparations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:867–872. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKAZAWA A., KAWIKOVA I., CUI Z.H., SKOOGH B.E., LOTVALL J. 8-Epi-PGF2α induces airflow obstruction and airway plasma exudation in vivo. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1997;155:436–441. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATICÒ D., BARRY O.P., LAWSON J.A., ADIYAMAN M., HWANG S.W., KHANAPURE S.P., IULIANO L., ROKACH J., FITZGERALD G.A. IPF2alpha-I: an index of lipid peroxidation in humans. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998a;95:3449–3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATICÒ D., BASILI S., VIERI M., CORDOVA C., VIOLI F., FITZGERALD G.A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with an increase in urinary levels of isoprostane F2alpha-III, an index of oxidant stress. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1998b;158:1709–1714. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9709066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QIAN Y.-M., JONES R.L., CHAN K.-M., STOCK A.I., HO J.K.S. Potent contractile actions of prostanoid EP3-receptor agonists on human isolated pulmonary artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb16997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REILLY M., DELANTY N., LAWSON J.A., FITZGERALD G.A. Modulation of oxidant stress in vivo in chronic cigarette smokers. Circ. 1996;94:19–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEEHAN D.W., GIESE E.C., GUGINO S.F., RUSSELL J.A. Characterization and mechanisms of H2O2-induced contractions of pulmonary arteries. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:H1542–H1547. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.5.H1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMLYO A.P., SOMLYO A.V. Signal transduction by G-proteins, Rho-kinase and protein phosphatase to smooth muscle and non-muscle myosin II. J. Physiol. 2000;522.2:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VACCHIANO C.A., TEMPEL G.E. Role of nonenzymatically generated prostanoid, 8-iso-PGF2α in pulmonary oxygen toxicity. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994;77:2912–2917. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALCH L., LABAT C., GASCARD J.-P., DE MONTPREVILLE V., DULMET E., BRINK C. Prostanoid receptors involved in the relaxation of human pulmonary vessels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:859–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]