Abstract

Protein synthesis dependency and the role of endogenously generated platelet activating factor (PAF) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4) in leukocyte migration through interleukin-1β (IL-1β)- and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-stimulated mouse cremasteric venules was investigated using established pharmacological interventions and the technique of intravital microscopy.

Based on previously obtained dose-response data, 30 ng rmIL-1β and 300 ng rmTNFα were injected intrascrotally (4 h test period) to induce comparable levels of leukocyte firm adhesion and transmigration in mouse cremasteric venules.

Co-injection of the mRNA synthesis inhibitor, actinomycin D (0.2 mg kg−1), with the cytokines significantly inhibited firm adhesion (49±13.6%) and transmigration (67.2±4.2%) induced by IL-1β, but not TNFα.

In vitro, TNFα (1–100 ng ml−1), but not IL-1β, stimulated L-selectin shedding and increased β2 integrin expression on mouse neutrophils, as quantified by flow cytometry.

The PAF receptor antagonist, UK-74,505 (modipafant, 0.5 mg kg−1, i.v.), had no effect on adhesion induced by either cytokine, but significantly inhibited transmigration induced by IL-1β (66.5±4.5%).

The LTB4 receptor antagonist, CP-105,696 (100 mg kg−1, p.o.), significantly inhibited both IL-1β induced adhesion (81.4±15.2%) and transmigration (58.7±7.2%), but had no effect on responses elicited by TNFα. Combined administration of the two antagonists had no enhanced inhibitory effects on responses induced by either cytokine.

The data indicate that firm adhesion and transmigration in mouse cremasteric venules stimulated by IL-1β, but not TNFα, is protein synthesis dependent and mediated by endogenous generation of PAF and LTB4. Additionally, TNFα but not IL-1β, can directly stimulate mouse neutrophils in vitro. The findings provide further evidence to suggest divergent mechanisms of actions of IL-1β and TNFα, two cytokines often considered to act via common molecular/cellular pathways.

Keywords: Cytokine, inflammation, intravital microscopy, leukocyte, chemoattractant

Introduction

IL-1β and T NFα are multifunctional cytokines with potent immunomodulatory and pro-inflammatory properties (Dinarello, 2000; Kunkel et al., 1991; Larrick & Kunkel, 1988). These cytokines can be generated during both acute and chronic phases of an inflammatory response and as such have been implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of inflammatory disease states, such as rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease (Brennan et al., 1992; Cominelli et al., 1990; Cominelli & Dinarello, 1989; Fiotti et al., 1999; Haraoui et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2001; Kollias et al., 1999; Maini et al., 1995; Ross, 1993; Schiff, 2000). Both cytokines can enhance the adhesiveness of endothelial cells for leukocytes in vitro (Bevilacqua et al., 1987; 1989; Bochner et al., 1991; Dustin et al., 1986; Osborn et al., 1989; Pober et al., 1986) and are potent inducers of leukocyte accumulation in vivo (Cybulsky et al., 1989; Issekutz et al., 1981; Nourshargh et al., 1989; Perretti & Flower, 1994; Rampart et al., 1989a; Rampart & Williams, 1988; Sanz et al., 1995; 1997), responses that are largely attributed to the ability of the cytokines to induce the expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (Bevilacqua et al., 1987; 1989; Bochner et al., 1991; Dustin et al., 1986; Osborn et al., 1989; Pober et al., 1986). The pro-inflammatory properties of IL-1β and TNFα also includes their ability to stimulate the release of other inflammatory mediators, such as chemokines, PAF and eicosanoids (Barnes et al., 1998; Brain & Williams, 1990; Bussolino et al., 1988; Huber et al., 1991; Strieter et al., 1989). Given their overlapping properties, such as those exemplified above, IL-1β and TNFα are frequently used in an interchangeable manner in both in vitro and in vivo inflammatory models and are commonly considered to exert their pro-inflammatory effects via similar molecular and cellular pathways.

There is, however, evidence for diverse modes of actions of IL-1β and TNFα. For example, in vitro studies have shown that TNFα can induce human neutrophil degranulation and generation of superoxide anions from adherent leukocytes (Nathan & Sporn, 1991) and stimulate rapid adhesion of human and murine neutrophils to cultured endothelial cells or protein-coated plates, respectively (Gamble et al., 1985; Thompson et al., 2001). No such stimulatory effects have been reported for IL-1β. In vivo, Rampart et al. (1989b) demonstrated that intradermal injection of IL-1β induced a slow (maximum within 3–4 h) and protein synthesis dependent neutrophil accumulation response in rabbit skin, whilst neutrophil accumulation induced by TNFα was rapid (maximum within 30 min) and protein synthesis independent. Furthermore, we have recently found that neutrophil transmigration through mouse cremasteric venules induced by IL-1β, but not TNFα, is suppressed in platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) deficient mice (Thompson et al., 2001). The aim of the present study was to extend these observations by investigating the existence of further differences in the mechanisms by which these cytokines elicit leukocyte migration from the vascular lumen to the extravascular tissue. For this purpose, we have used well-characterized pharmacological interventions and the technique of intravital microscopy to investigate the protein synthesis dependency and the role of endogenously generated PAF and LTB4 in the different stages of leukocyte migration through mouse cremasteric venules stimulated by IL-1β and TNFα. The results provide further evidence for the divergent mechanisms of action of these cytokines and demonstrate a clear involvement for endogenously generated LTB4 and PAF in IL-1β-induced, but not TNFα-induced, leukocyte firm adhesion and transmigration, respectively.

Methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (20–25 g, Harlan-Olac, Bicester, U.K.) were used for all experiments.

Intravital microscopy

Intravital microscopy was used to observe cytokine elicited leukocyte responses within mouse cremasteric venules, following intrascrotal (i.s.) administration of IL-1β (30 ng in 400 μl) or TNFα (300 ng in 400 μl), as compared to responses in animals injected with i.s. saline (400 μl). To assess the role of protein synthesis, the RNA transcription inhibitor, actinomycin D (Act D, 0.2 mg kg−1), was co-administered i.s. with saline or cytokines. The roles of endogenously generated PAF and LTB4 in cytokine-induced responses were investigated by using the selective PAF and LTB4 receptor antagonists, UK-74,505 (modipafant; Alabaster et al., 1991) and CP-105,696 (Koch et al., 1994), respectively. UK-74,505, initially made up at 15 mg ml−1 in 0.1 M hydrochloric acid and then diluted with saline, was administered intravenously (i.v.) at the dose of 0.5 mg kg−1 10 min before i.s. injection of cytokines or saline control. CP-105,696 was administered as an oral suspension in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose at the dose of 100 mg kg−1 19 h prior to the i.s. injection of cytokine or saline. Some groups of mice were pre-treated with both UK-74,505 and CP-105,696 or their corresponding vehicles.

Four hours after cytokine injection, the mice were prepared for intravital microscopy as previously described (Ley et al., 1995; Thompson et al., 2001). After induction of anaesthesia with ketamine (100 mg kg−1) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1) by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, animals were maintained at 37°C on a custom-built heated Perspex microscope stage. The cremaster muscle was exteriorized through an incision in the scrotum and one testis gently drawn out to allow the cremaster muscle to be opened and pinned out flat over the optical window within the microscope stage. The tissue was kept warm and moist throughout each experiment by superfusion of warmed Tyrode's balanced salt solution. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions were observed on an upright fixed-stage microscope (Axioscop FS, Carl Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, U.K.) fitted with water immersion objectives. Video recordings were made with a chilled colour video camera (C5810-01, Hamamatsu Photonics, Enfield, U.K.) and S-VHS videocassette recorder (AG-MD830E, Panasonic, Bracknell, U.K.). Leukocyte responses of rolling, firm adhesion and transmigration in postcapillary venules of 20–40 μm diameter were quantified as previously detailed (Nourshargh et al., 1995). Briefly, leukocyte rolling flux was quantified as the number of rolling cells moving past a fixed point on the venular wall per minute, averaged over 5 min. Firmly adherent leukocytes were considered as those remaining stationary for at least 30 s within a given 100 μm vessel segment. Transmigrated leukocytes were quantified as those in the extravascular tissue within 50 μm of the 100 μm vessel segments quantified. In each animal, responses in several vessel segments (3–5), from multiple vessels (3–5), were studied and averaged.

In selected experiments, microvascular centreline erythrocyte velocity and peripheral leukocyte counts were determined. With respect to the former, centreline velocity was quantified using a Doppler velocimeter (Microvessel Velocity OD-RT, CircuSoft Instrumentation LLC, Hockessin, DE, U.S.A.) and in each animal, values from at least three vessels were determined. With respect to leukocyte counts, blood samples were collected from tail veins into acid citrate dextrose (ACD) and total and differential leukocyte counts were carried out using a haemocytometer following the staining of blood samples with Kimura.

Flow cytometry

Whole blood was taken by cardiac puncture from donor animals and diluted 50 : 50 with anti-coagulant (20 mM EDTA in 1×PBS). The blood was incubated for 20 min at room temperature with a range of concentrations (1–100 ng ml−1) of IL-1β and TNFα, PMA (100 ng ml−1) as a positive control and with PBS (supplemented with 1 mM Ca2+ and Mg2+) used as vehicle control. After washing, samples were incubated with primary monoclonal antibody (mAb) directed against either L-selectin (MEL-14, IgG2a, PharMingen, Oxford, U.K.) or β2 integrin (GAME-46, IgG1, PharMingen, Oxford, U.K.) on ice and the binding of test mAbs was detected with a F(ab′)2 FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Serotec Ltd, Oxford, U.K.) antibody. Isotype-matched controls (PharMingen, Oxford, U.K.) were also used in all experiments. Erythrocytes were lysed by treating the samples with a FACS lysing reagent (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, U.K.) before analysing the samples on an EPICS XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, U.K.). Gating on neutrophils was based on characteristic forward and side scatter parameters as well as the binding of the mAb, Gr-1 (PharMingen, Oxford, U.K.). The ratio of fluorescence intensities associated with the binding of primary mAbs and isotype-matched control mAbs was used to express specific binding of test mAbs in terms of relative fluorescence intensity (RFI).

Drugs and reagents

The following reagents were purchased: recombinant murine IL-1β and TNFα (Serotec, Oxford, U.K.); ketamine (Ketalar, Parke-Davis, Eastleigh, U.K.); xylazine (Rompun, Bayer, Bury St. Edmunds, U.K.); LTB4 (Calbiochem, U.K.); ACD (Baxter Healthcare Ltd, Newbury, U.K.); MEL-14, GAME-46, Gr-1 and isotype matched controls (PharMingen, Oxford, U.K.); FACS lysing reagent (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, U.K.); F(ab′)2 FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Serotec Ltd, Oxford, U.K.). UK-74,505 [4-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,4-dihydro-3-(ethoxycarbonyl)-6-methyl-2-[4-(2-methyamidazo[4,5-c-pyrid-1-yl)-5-[N-(2-pyridyl)carbamoyl]pyridine)] (modipafant; Alabaster et al., 1991; Cooper et al., 1992; Pons et al., 1993) and CP-105,696 [(+)-1-(3S,4R)-[3-(4-phenyl-benzyl)-4-hydroxy-chroman-7-yl]-cyclopentane carboxylic acid] (Koch et al., 1994; Showell et al., 1996) were gifts from Pfizer, Sandwich, U.K., and Pfizer, Groton, CT, U.S.A., respectively. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, U.K.).

Statistical analysis

Results are given as mean±s.e.mean, unless otherwise stated, and analysed using either an unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls post test with P<0.05 taken as significant (Prism, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Results

Effect of actinomycin D on leukocyte responses elicited by IL-1β and TNFα

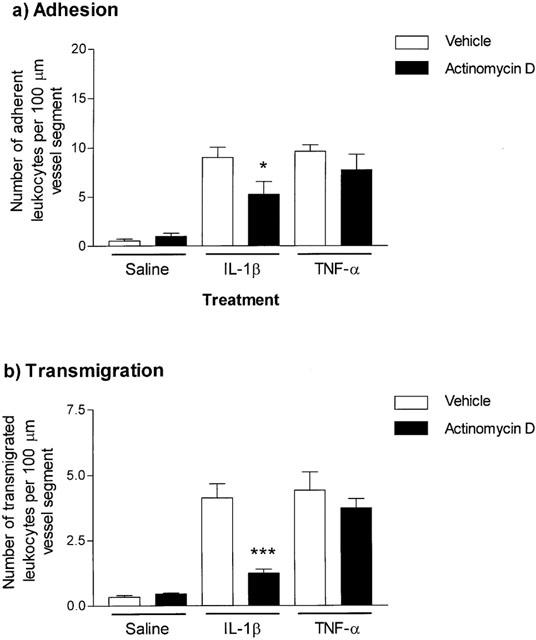

Based on previous dose-response data (Thompson et al., 2001), IL-1β and TNFα were administered intrascrotally at the doses of 30 ng and 300 ng respectively and 4 h later leukocyte responses within mouse cremasteric venules were observed and quantified by intravital microscopy. Figure 1 shows that at these doses the cytokines elicited comparable and significant levels of leukocyte firm adhesion and transmigration as compared to animals injected with intrascrotal saline. No significant change in leukocyte rolling flux was observed with IL-1β or TNFα as compared to saline-injected mice (data not shown). The role of local protein synthesis in leukocyte responses induced by the cytokines was investigated using the transcription inhibitor, actinomycin D. When co-administered with IL-1β, actinomycin D (0.2 mg kg−1), significantly suppressed leukocyte firm adhesion (49.0±13.6%; P<0.05) and transmigration (67.2±4.2%; P<0.001) as compared to responses elicited by the cytokine alone (Figure 1a,b). In contrast, actinomycin D had no effect on TNFα-induced leukocyte adhesion and transmigration (Figure 1a,b). Local administration of actinomycin D had no effect on blood flow within the cremaster muscle venules or on peripheral blood leukocyte counts (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of the protein synthesis inhibitor, actinomycin D, on IL-1β- or TNFα-induced leukocyte adhesion and transmigration in mouse cremasteric venules. Mice were injected intrascrotally with saline (400 μl), IL-1β (30 ng in 400 μl saline) or TNFα (300 ng in 400 μl saline) with or without actinomycin D (0.2 mg kg−1) and leukocyte firm adhesion (a) and transmigration (b), per 100 μm vessel segment, were quantified by intravital microscopy 4 h later, as detailed in Methods. Results are presented as mean±s.e.mean for n=5 mice per group. Statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls post-test) between control and drug-treated groups are shown by asterisks, *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001.

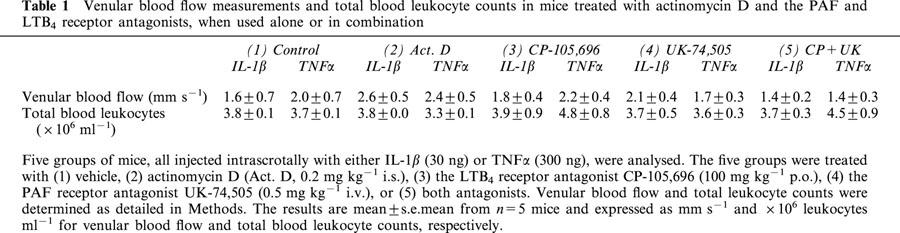

Table 1.

Venular blood flow measurements and total blood leukocyte counts in mice treated with actinomycin D and the PAF and LTB4 receptor antagonists, when used alone or in combination

Effect of IL-1β and TNFα on cell surface expression of L-selectin and β2 integrins on mouse neutrophils

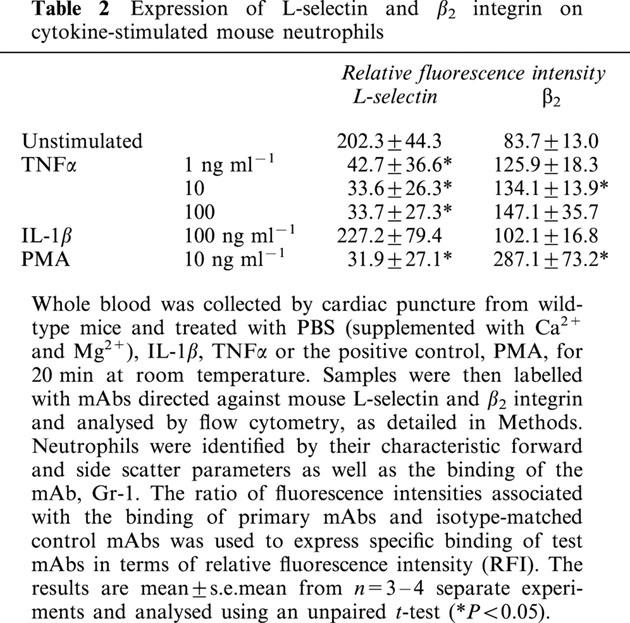

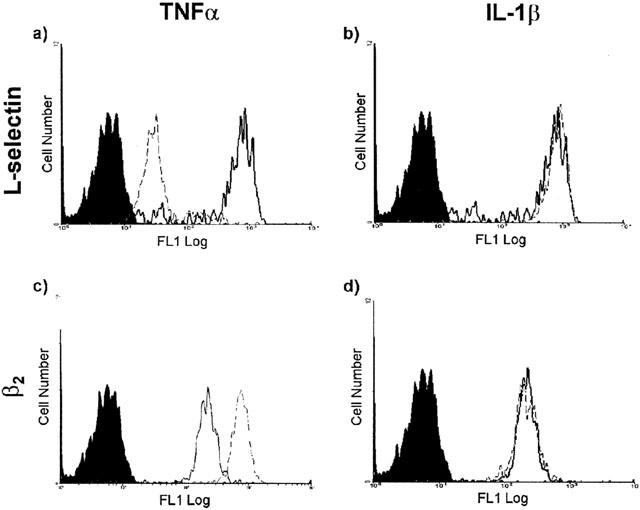

Since a potential explanation for the findings of the above experiments is that TNFα may be directly stimulating mouse neutrophils, the aim of the following studies was to address this possibility by investigating the effect of TNFα on regulation of expression of the adhesion molecules L-selectin and β2 integrin on mouse neutrophils. For this purpose, mouse whole blood was stimulated with IL-1β and TNFα (1–100 ng ml−1), for 20 min, and cell surface expression of L-selectin and β2 quantified by indirect immunofluorescent staining and flow cytometry, as detailed in Methods. The concentrations of the cytokines employed were based on previous investigations from our own group (Thompson et al., 2001) and other researchers (Bochner et al., 1991; Brandt et al., 1992; Christofidou-Solomidou et al., 1997; Takahashi et al., 2001). The results in Table 2 and Figure 2 clearly demonstrate that TNFα dose-dependently enhanced cell surface expression of β2 integrin (significant at 10 ng ml−1) and the shedding of L-selectin (significant for all concentrations investigated). The potent leukocyte stimulant, PMA, gave a similar profile of responses to that observed with TNFα. In contrast, IL-1β-stimulated samples failed to show any significant change in cell surface expression of molecules as compared to unstimulated samples.

Table 2.

Expression of L-selectin and β2 integrin on cytokine-stimulated mouse neutrophils

Figure 2.

Effect of TNFα and IL-1β on expression of L-selectin and β2 integrin on mouse neutrophils. Figure shows representative fluorescence histograms comparing cell surface expressions of L-selectin and β2 integrins on unstimulated and cytokine stimulated mouse neutrophils. Briefly, blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture and stimulated with the cytokines (both at 100 ng ml−1) at room temperature for 20 min prior to labelling with isotype-matched control mAbs or mAbs directed against L-selection (a/TNFα and b/IL-1β) and β2 (c/TNFα and d/IL-1β), followed by incubation with a FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 mAb. Samples were analysed by flow cytometry as described in Methods. The filled tracings are from blood samples incubated with an isotype-matched control mAb, solid lines represent unstimulated cells and dashed lines represent stimulated cells. The histograms represent the cell number relating to the expression of the molecule examined and are representative of four separate experiments.

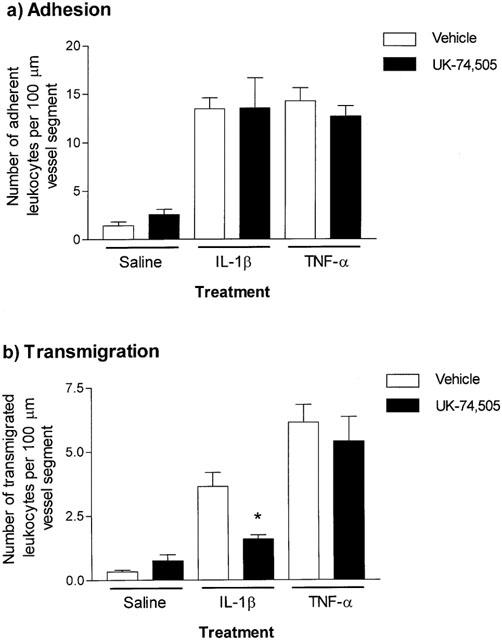

Effect of the PAF receptor antagonist UK-74,505 on leukocyte responses elicited by IL-1β and TNFα

To further investigate potential differences in mechanisms of actions of the two cytokines, the role of endogenously generated PAF in leukocyte responses elicited by IL-1β and TNFα was investigated using the selective PAF receptor antagonist UK-74,505 (Alabaster et al., 1991; Cooper et al., 1992). Based on previous studies in mice (Miotla et al., 1998), rats (Sanz et al., 1995) and rabbits (Pons et al., 1993), animals were injected intravenously with this antagonist at the dose of 0.5 mg kg−1. In mice treated with UK-74,505, no significant effects on leukocyte firm adhesion induced by either cytokine were observed (Figure 3a). However, leukocyte transmigration elicited by IL-1β was significantly inhibited (66.5±4.5%, P<0.05), while TNFα-induced transmigration was unaffected (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Effect of the PAF receptor antagonist, UK-74,505, on IL-1β- or TNFα-induced leukocyte adhesion and transmigration in mouse cremasteric venules. Mice were pretreated with vehicle or UK-74,505 (0.5 mg kg−1, i.v.) 10 min before the intrascrotal administration of saline (400 μl), IL-1β (30 ng in 400 μl saline) or TNFα (300 ng in 400 μl saline). Four hours later, leukocyte responses of adhesion (a) and transmigration (b), per 100 μm vessel segment, were quantified by intravital microscopy, as detailed in Methods. Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n=5 mice per group. Statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA and Newman–Keuls post-test) between vehicle and drug-treated groups are shown by asterisks, *P<0.05.

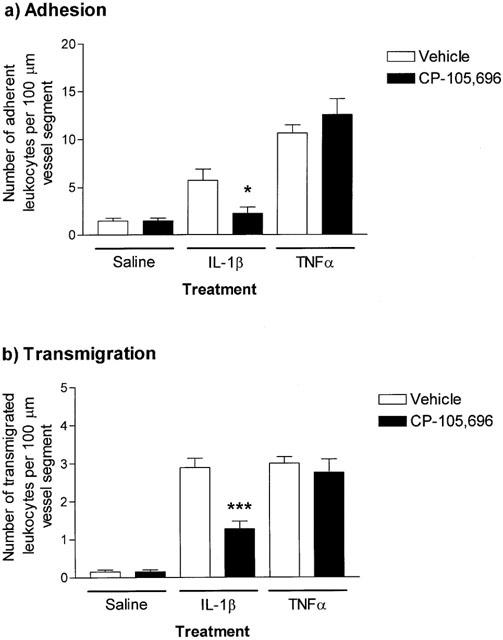

Effect of the LTB4 receptor antagonist CP-105,696 on leukocyte responses elicited by IL-1β and TNFα

The LTB4 receptor antagonist, CP-105,696 (Koch et al., 1994; Showell et al., 1996), was used to investigate the role of endogenously generated LTB4 in IL-1β- and TNFα-induced leukocyte responses. In mice treated with this antagonist (100 mg kg−1, p.o., 19 h prior to intrascrotal injection of cytokines), leukocyte firm adhesion and transmigration induced by IL-1β was significantly inhibited by 81.4±15.2% (P<0.05) and 58.7±7.2% (P<0.05), respectively (Figure 4a,b). In contrast, CP-105,696 had no effect on leukocyte responses induced by TNFα (Figure 4a,b). Additional analysis of the data for IL-1β, involving calculation of the ratio of adherent to transmigrated leukocytes as a measure of the fraction of adherent leukocytes that transmigrated, suggested that the inhibitory effect of the CP-105,696 compound was most likely at the stage of adhesion and not transmigration (a ratio of 1.76 for CP-105,696-treated animals compared with 2.00 for control-treated animals). Of importance, in cremasteric venules stimulated with IL-1β, topical LTB4 could induce a further increase in leukocyte responses in control mice but not CP-105,696-treated animals, demonstrating that the dosing regime employed for the administration of the antagonist was effective at abrogating LTB4 elicited responses in this model (data not shown).

Figure 4.

The effect of the LTB4 receptor antagonist, CP-105,696, on IL-1β- and TNFα-induced leukocyte adhesion and transmigration in mouse cremasteric venules. Mice were pretreated with vehicle or CP-105,696 (100 mg kg−1, p.o.) 19 h prior to intrascrotal administration of saline (400 μl), IL-1β (30 ng in 400 μl saline) or TNFα (300 ng in 400 μl saline). Four hours later, leukocyte responses of adhesion (a) and transmigration (b), per 100 μm vessel segment, were quantified by intravital microscopy, as detailed in Methods. Values represent mean±s.e.mean of n=5 mice per group. Statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls post-test) between vehicle and drug-treated groups are shown by asterisks, *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001.

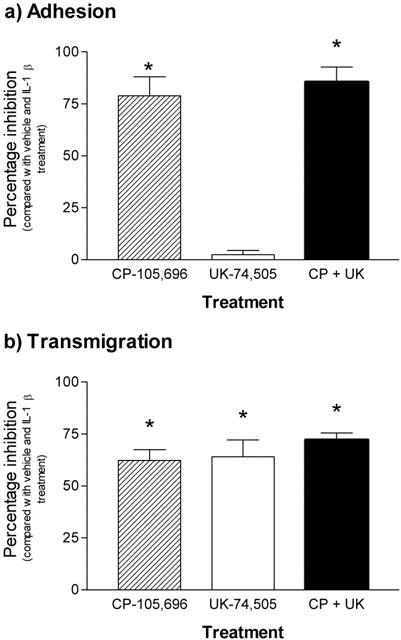

Effect of combined PAF and LTB4 receptor antagonist treatment on cytokine-induced responses

In a final series of experiments, the effect of combined treatment of mice with both the PAF and LTB4 receptor antagonist, using the dosing regimes detailed above, was investigated. For clarity, the data from these experiments are compared with data obtained in parallel experiments when each antagonist was used alone, and expressed as percentage inhibition of cytokine-induced responses. Hence, as previously found, Figure 5a shows that IL-1β-induced leukocyte firm adhesion was significantly inhibited by the LTB4 receptor antagonist, CP-105,696, but not the PAF receptor antagonist, UK-74,505. Furthermore, treatment of mice with both antagonists resulted in a similar inhibition to that observed with the LTB4 receptor antagonist alone. The combined treatment of mice with the two antagonists also led to a similar level of inhibition of IL-1β-induced transmigration as that observed with either antagonist alone (Figure 5b). The combined administration of the PAF and LTB4 receptor antagonists, as found when the antagonists were administered alone, had no effect on responses induced by TNFα (data not shown). Of relevance to the whole study, treatment of mice with the antagonists, when administered alone or in combination, had no effect on blood flow or leukocyte blood counts as compared with vehicle-treated control mice (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Effect of combined administrations of PAF (UK-74,505) and LTB4 (CP-105,696) receptor antagonists on IL-1β-induced leukocyte adhesion and transmigration in mouse cremasteric venules. Mice were pretreated with CP-105,696 (100 mg kg−1, p.o., 19 h prior to the intrascrotal injection of saline or 30 ng IL-1β), UK-74,505 (0.5 mg kg−1 i.v., 10 min prior to intrascrotal injection of saline or 30 ng IL-1β), or both antagonists. The results are presented as percentage inhibition of leukocyte adhesion (a) and transmigration (b) as compared to responses obtained in animals treated with appropriate vehicles and intrascrotal IL-1β, following subtraction of responses detected in mice treated with intrascrotal saline. Values represent mean±s.e.mean from n=5 mice per group. Statistically significant difference (one-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls post-test) from vehicle treated groups is shown by asterisks, *P<0.05.

Discussion

The pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNFα, have many overlapping properties and as such are often used within experimental inflammatory models interchangeably. However, a number of studies have also demonstrated key differences in the mechanisms of action of these cytokines suggesting divergence in their molecular and cellular targets (Rampart et al., 1989b; Nathan & Sporn, 1991; Thompson et al., 2001). The aim of the present study was to further investigate differences in the mechanisms of action of these cytokines by specifically examining the contribution of protein synthesis and the endogenously generated phospholipid mediators, PAF and LTB4, in different stages of leukocyte migration elicited by IL-1β and TNFα. For this purpose the effect of the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D and PAF or LTB4 receptor antagonists on leukocyte migration through cytokine-stimulated cremasteric venules, as observed by intravital microscopy, was investigated. In addition, the study provides data demonstrating that TNFα, but not IL-1β, can regulate the cell surface expression of the adhesion molecules L-selectin (down-regulation) and β2 integrins (up-regulation) on mouse neutrophils. Collectively, the findings suggest that leukocyte adhesion and/or transmigration induced by IL-1β, but not TNFα, is mediated by endogenously generated proteins and the lipid mediators, PAF and LTB4, whilst TNFα-induced responses may be at least partly mediated via direct stimulation of mouse neutrophils. The present findings add to the growing list of important mechanistic differences in the pro-inflammatory actions of these cytokines.

Local administration of IL-1β or TNFα into the mouse cremaster muscle induced significant leukocyte adhesion and transmigration responses as compared to the local injection of saline, as previously reported (Thompson et al., 2001). The involvement of locally generated proteins in these responses was investigated by using the RNA synthesis inhibitor, actinomycin D. Co-administration of actinomycin D with the cytokines markedly suppressed leukocyte adhesion (49%) and transmigration (67%) induced by IL-1β, but had no effect on responses elicited by TNFα. The present observations are in agreement with the findings of Rampart and colleagues who reported that the accumulation of 111In-neutrophils in rabbit skin in response to IL-1β, but not TNFα, was protein synthesis dependent (Rampart & Williams, 1988; Rampart et al., 1989b). Interestingly, using a very similar model, Cybulsky et al. (1989) found that neutrophil accumulation into rabbit skin induced by both IL-1β and TNFα was blocked by local administration of protein synthesis inhibitors. The reason for the difference between our findings and those of Rampart and colleagues as compared to the results reported by Cybulsky et al. is unclear, but may be related to the species and/or doses of cytokines and inhibitors employed in the different studies.

Since one potential explanation for the above findings is that TNFα, but not IL-1β, may be directly stimulating mouse neutrophils, as part of the present investigation the effect of the cytokines on regulation of expression of the adhesion molecules L-selectin and β2 integrins was investigated. The results clearly demonstrated the ability of TNFα to induce rapid shedding of L-selectin and upregulation of β2 integrins on mouse neutrophils in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, IL-1β was found to be without any such effects. Of direct relevance, we have previously found that TNFα, but not IL-1β, can stimulate the adhesion of murine neutrophils to protein-coated plates (Thompson et al., 2001). Furthermore, Gamble et al. (1985) demonstrated that TNFα could stimulate neutrophil adhesion to cultured endothelial cells through effects on both cell types, though the effect on neutrophils was rapid (5 min) and protein synthesis independent whilst the effect on endothelial cells was slow (4 h) and dependent on de novo protein generation. Evidence for the ability of TNFα to directly stimulate mouse neutrophils leading to firm adhesion is also suggested by the in vivo observations of Thorlacius et al. (2000), where it was found that topical application of TNFα to the mouse cremaster muscle induced an LFA-1-dependent increase in leukocyte firm adhesion within a 30 min test-period.

Collectively, the above in vitro and in vivo findings strongly indicate that in IL-1β-stimulated cremasteric venules, locally generated proteins are involved in mediating leukocyte adhesion to and migration through endothelial cells. In contrast however, the results suggest that leukocyte responses elicited by TNFα occur independently of local protein synthesis and that in eliciting acute neutrophil migration, the principal target cell of TNFα may be the neutrophil itself or cells resident within the tissue (e.g. mast cells). This property of TNFα may be associated with direct neutrophil stimulatory effects of the cytokine leading to cellular responses such as enhanced adhesion, and/or with the ability of TNFα to stimulate the rapid release of preformed protein or lipid mediators, such as IL-8 or LTB4, from adherent neutrophils.

Proteins mediating IL-1β-induced leukocyte responses may include recognition and/or activation structures such as adhesion molecules (e.g. ICAM-1) (Oppenheimer-Marks et al., 1991) and inflammatory mediators (e.g. the chemokine, IL-8) (Mccoll & Clark-Lewis, 1999), respectively. In addition, IL-1β may be inducing the expression of enzymes, such as phospholipase A2, lyso-PAF acetyl transferase or 5-lipoxygenase, that are responsible for the synthesis of inflammatory mediators, such as PAF and LTB4, as suggested by in vitro studies (Bussolino et al., 1988; Jackson et al., 1993; Nassar et al., 1997; Schwemmer et al., 2001). To investigate the roles of endogenously generated PAF and LTB4 in leukocyte migration through IL-1β-stimulated venules, in comparison with responses elicited by TNFα, the selective PAF and LTB4 receptor antagonists, UK-74,505 (modipafant; Alabaster et al., 1991) and CP-105,696 (Koch et al., 1994), respectively, were used. Pretreatment of mice with the PAF antagonist had no effect on IL-1β-induced leukocyte adhesion but markedly inhibited leukocyte transmigration elicited by this cytokine (66.5%). These results are in agreement with our previous findings investigating leukocyte migration through rat mesenteric venules as observed by intravital microscopy (Nourshargh et al., 1995) and the in vitro findings of Kuijpers et al. (1992). Interestingly, this suppression appeared to occur at the level of the endothelium, as determined by transmission electron microscopy (R.D. Thompson and S. Nourshargh, unpublished observations), indicating a role for locally generated PAF in leukocyte migration through endothelial cells as opposed to leukocyte migration through the perivascular basement membrane, induced by IL-1β. The precise mechanism by which IL-1β-induced PAF mediates this response is unclear. However, since the majority of the PAF generated by endothelial cells remains cell bound (typically 70–80%) (Bussolino et al., 1986; 1988; Camussi et al., 1987), endothelial cell associated PAF may (1) act in a haptotactic manner to guide the firmly adherent leukocytes through endothelial cell junctions, or (2) may stimulate the adherent leukocytes so that the expression profile of their cell surface molecules changes in favour of leukocyte migration as opposed to firm adhesion. Finally, (3) PAF may regulate the function and/or ligand binding profile of junctional endothelial cell adhesion molecules, and hence facilitate transmigration. In this context, PAF receptor antagonists have been shown to abolish both PECAM-1 phosphorylation induced by endothelial cell activation, and subsequent monocyte transmigration in vitro (Kalra et al., 1996). Despite the reported ability of TNFα to stimulate PAF generation in different cell systems (Alloatti et al., 2000; Bussolino et al., 1990; Myers et al., 1990), in our studies, leukocyte transmigration in response to TNFα was unaffected by PAF receptor blockade. These findings suggest that in the present model, TNFα-induced leukocyte migration occurred independently of endogenously generated PAF, illustrating yet another important mechanistic difference between the responses elicited by IL-1β and TNFα. Interestingly, PAF antagonists have no inhibitory effects on leukocyte transmigration elicited by the direct neutrophil chemoattractant FMLP both in vitro (Kuijpers et al., 1992) and in vivo (Nourshargh et al., 1995), yet again suggesting that TNFα may be acting in a similar manner to direct neutrophil chemoattractants and eliciting neutrophil transmigration via direct neutrophil stimulation.

In mice pre-treated with the LTB4 receptor antagonist, IL-1β-induced leukocyte adhesion and transmigration were significantly suppressed (81 and 59%, respectively). On analysing the ratio of transmigrated leukocytes to adherent leukocytes, a similar ratio was obtained in mice treated with vehicle and mice treated with the LTB4 antagonist, suggesting that the observed inhibition of leukocyte transmigration was directly associated with the inhibition of leukocyte adhesion. Hence, collectively, the present results suggest that whilst IL-1β-induced firm adhesion is mediated by endogenously generated LTB4, transmigration through IL-1β-stimulated venules is mediated by endogenously generated PAF. Alternatively, protein mediators such as IL-8 induced in response to IL-1β (from endothelial cells or other tissue cells) may in turn stimulate adherent leukocytes to generate additional inflammatory mediators, such as LTB4, that may act in an autocrine manner to further stimulate the activation of leukocyte integrins, hence contributing to the adhesive response (Marleau et al., 1999). The adherent leukocytes can then become activated and/or guided through endothelial cell junctions via endothelial cell associated PAF, as discussed above. As found with actinomycin D and the PAF receptor antagonist, the LTB4 antagonist had no effect on leukocyte responses induced by TNFα. However, since IL-1β and TNFα can reportedly stimulate the generation of both LTB4 and PAF (Alloatti et al., 2000; Borish et al., 1990; Bussolino et al., 1988; 1990; Camussi et al., 1989), to investigate the potential additive or synergistic effects of these mediators in leukocyte migration elicited by the two cytokines, in a final series of experiments, mice were pretreated with both receptor antagonists. The results indicated that co-administration of the blockers did not lead to a greater inhibitory effect than that observed when the antagonists were administered alone, suggesting that the two lipid mediators did not act in a cooperative manner.

In summary, the results of the present study strongly suggest that TNFα can stimulate leukocyte responses of firm adhesion and transmigration within the mouse cremaster microcirculation without the need for local protein synthesis or the generation of the pro-inflammatory lipid mediators PAF and LTB4. In conjunction with previously published results (discussed above), the present findings support the hypothesis that TNFα can induce leukocyte migration via direct effects on leukocytes and/or tissue inflammatory cells, such as mast cells, capable of releasing pre-formed protein mediators in response to TNFα (van overveld et al., 1991). In contrast, leukocyte firm adhesion to and transmigration through IL-1β-stimulated cremasteric venules was dependent on local generation of proteins and indicated that in the present model, IL-1β-induced leukocyte firm adhesion was dependent on endogenously generated LTB4, whilst transmigration was strongly mediated by endogenously generated PAF. As well as identifying components of the leukocyte migration response elicited by IL-1β, the present study has also directly compared the effects of IL-1β and TNFα in a commonly used inflammatory model and identified key differences in their mechanisms of action. A better understanding of the mechanisms of action of IL-1β and TNFα may aid the development of more specific anti-inflammatory therapies for disease states in which these cytokines have been implicated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank John Dangerfield for his valuable contribution to the flow cytometry experiments. This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council and The Wellcome Trust.

Abbreviations

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- LTB4

leukotriene B4

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- PAF

platelet activating factor

- PECAM-1

platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor α

References

- ALABASTER V.A., KEIR R.F., PARRY M.J., DE SOUZA R.N. UK-74,505, a novel and selective PAF antagonist, exhibits potent and long lasting activity in vivo. Agents Actions. 1991;34:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALLOATTI G., PENNA C., MARIANO F., CAMUSSI G. Role of NO and PAF in the impairment of skeletal muscle contractility induced by TNFα. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279:R2156–R2163. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F., PAGE C.P. Inflammatory mediators of asthma: an update. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:515–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEVILACQUA M.P., POBER J.S., MENDRICK D.L., COTRAN R.S., GIMBRONE M.A., JR Identification of an inducible endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:9238–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEVILACQUA M.P., STENGELIN S., GIMBRONE M.A., JR, SEED B. Endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1: an inducible receptor for neutrophils related to complement regulatory proteins and lectins. Science. 1989;243:1160–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.2466335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOCHNER B.S., LUSCINSKAS F.W., GIMBRONE M.A., JR, NEWMAN W., STERBINSKY S.A., DERSE-ANTHONY C.P., KLUNK D., SCHLEIMER R.P. Adhesion of human basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils to interleukin 1-activated human vascular endothelial cells: contributions of endothelial cell adhesion molecules. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1553–1557. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORISH L., ROSENBAUM R., MCDONALD B., ROSENWASSER L.J. Recombinant interleukin-1 beta interacts with high-affinity receptors to activate neutrophil leukotriene B4 synthesis. Inflammation. 1990;14:151–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00917454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAIN S.D., WILLIAMS T.J. Leukotrienes and inflammation. Pharmacol. Ther. 1990;46:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRANDT E., PETERSEN F., FLAD H.-D. Recombinant tumour necrosis factor-α potentiates neutrophil degranulation in response to host defense cytokines neutrophil-activating peptide 2 and IL-8 by modulating intracellular cyclic AMP levels. J. Immunol. 1992;149:1356–1364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNAN F.M., MAINI R.N., FELDMANN M. TNFα – a pivotal role in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1992;31:293–298. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.5.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSSOLINO F., BREVIARIO F., TETTA C., AGLIETTA M., SANAVIO F., MANTOVANI A., DEJANA E. Interleukin 1 stimulates platelet activating factor production in cultured human endothelial cells. Pharmacol. Res. Comm. 1986;18 Suppl:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0031-6989(86)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSSOLINO F., CAMUSSI G., BAGLIONI C. Synthesis and release of platelet-activating factor by human vascular endothelial cells treated with tumor necrosis factor or interleukin 1 alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:11856–11861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSSOLINO F., CAMUSSI G., TETTA C., GARBARINO G., BOSIA A., BAGLIONI C. Selected cytokines promote the synthesis of platelet-activating factor in vascular endothelial cells: comparison between tumor necrosis factor alpha and beta and interleukin-1. J. Lipid Mediators. 1990;2:S15–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMUSSI G., BUSSOLINO F., SALVIDIO G., BAGLIONI C. Tumor necrosis factor/cachectin stimulates peritoneal macrophages, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, and vascular endothelial cells to synthesize and release platelet-activating factor. J. Exp. Med. 1987;166:1390–1404. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMUSSI G., TETTA C., BUSSOLINO F., BAGLIONI C. Tumor necrosis factor stimulates human neutrophils to release leukotriene B4 and platelet-activating factor. Induction of phospholipase A2 and acetyl-CoA:1-alkyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine O2-acetyltransferase activity and inhibition by antiproteinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1989;182:661–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTOFIDOU-SOLOMIDOU M., NAKADA M.T., WILLIAMS J., MULLER W.A., DELISSER H.M. Neutrophil platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 participates in neutrophil recruitment at inflammatory sites and is down-regulated after leukocyte extravasation. J. Immunol. 1997;158:4872–4878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMINELLI F., DINARELLO C.A. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of and protection from inflammatory bowel disease. Biotherapy. 1989;1:369–375. doi: 10.1007/BF02171013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMINELLI F., NAST C.C., CLARK B.D., SCHINDLER R., LIERENA R., EYSSELEIN V.E., THOMPSON R.C., DINARELLO C.A. Interleukin 1 (IL-1) gene expression, synthesis, and effect of specific IL-1 receptor blockade in rabbit immune complex colitis. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;86:972–980. doi: 10.1172/JCI114799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOPER K., FRAY M.J., PARRY M.J., RICHARDSON K., STEELE J. 1,4-Dihydropyridines as antagonists of platelet activating factor. 1. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 2-(4-heterocyclyl)phenyl derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:3115–3129. doi: 10.1021/jm00095a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CYBULSKY M.I., MCCOMB D.J., MOVAT H.Z. Protein synthesis dependent and independent mechanisms of neutrophil emigration. Different mechanisms of inflammation in rabbits induced by interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha or endotoxin versus leukocyte chemoattractants. Am. J. Pathol. 1989;135:227–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINARELLO C.A. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;118:503–508. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUSTIN M.L., ROTHLEIN R., BHAN A.K., DINARELLO C.A., SPRINGER T.A. Induction by IL 1 and interferon-gamma: tissue distribution, biochemistry, and function of a natural adherence molecule (ICAM-1) J. Immunol. 1986;137:245–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIOTTI N., GIANSANTE C., PONTE E., DELBELLO C., CALABRESE S., ZACCHI T., DOBRINA A., GUARNIERI G. Atherosclerosis and inflammation. Patterns of cytokine regulation in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Atherosclerosis. 1999;145:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAMBLE J.R., HARLAN J.M., KLEBANOFF S.J., VADAS M.A. Stimulation of the adherence of neutrophils to umbilical vein endothelium by human recombinant tumor necrosis factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:8667–8671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARAOUI B., STRAND V., KEYSTONE E. Biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2000;1:217–233. doi: 10.2174/1389201003378915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG C.M., TSAI F.J., WU J.Y., WU M.C. Interleukin-1β and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphisms in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2001;30:225–228. doi: 10.1080/030097401316909576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUBER A.R., KUNKEL S.L., TODD R.F., III, WEISS S.J. Regulation of transendothelial neutrophil migration by endogenous interleukin-8. Science. 1991;254:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1718038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISSEKUTZ T.B., ISSEKUTZ A.C., MOVAT H.Z. The in vivo quantitation and kinetics of monocyte migration into acute inflammatory tissue. Am. J. Pathol. 1981;103:47–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACKSON B.A., GOLDSTEIN R.H., ROY R., COZZANI M., TAYLOR L., POLGAR P. Effects of transforming growth factor β and interleukin-1β on expression of cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 and phospholipase-A2 mRNA in lung fibroblasts and endothelial cells in culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;197:1465–1474. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALRA V.K., SHEN Y., SULTANA C., RATTAN V. Hypoxia induces PECAM-1 phosphorylation and transendothelial migration of monocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H2025–H2034. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.5.H2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOCH K., MELVIN L.S., JR, REITER L.A., BIGGERS M.S., SHOWELL H.J., GRIFFITH R.J., PETTIPHER E.R., CHENG J.B., MILICI A.J., BRESLOW R. (+)-1-(3S,4R)-[3-(4-phenylbenzyl)-4-hydroxychroman-7-yl]cyclopentane carboxylic acid, a highly potent, selective leukotriene B4 antagonist with oral activity in the murine collagen-induced arthritis model. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:3197–3199. doi: 10.1021/jm00046a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLLIAS G., DOUNI E., KASSIOTIS G., KONTOYIANNIS D. The function of tumour necrosis factor and receptors in models of multi-organ inflammation, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1999;58:I32–I39. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.2008.i32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUIJPERS T.W., HAKKERT B.C., HART M.H., ROOS D. Neutrophil migration across monolayers of cytokine-prestimulated endothelial cells: a role for platelet-activating factor and IL-8. J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:565–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.3.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNKEL S., STANDIFORD T., CHENSUE S.W., KASAHARA K., STRIETER R.M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of cytokine networking. Agents Actions. 1991;32:205–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7405-2_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARRICK J.W., KUNKEL S.L. The role of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 in the immunoinflammatory response. Pharm. Res. 1988;5:129–139. doi: 10.1023/a:1015904721223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEY K., BULLARD D.C., ARBONES M.L., BOSSE R., VESTWEBER D., TEDDER T.F., BEAUDET A.L. Sequential contribution of L- and P-selectin to leukocyte rolling in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:669–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAINI R.N., ELLIOTT M.J., BRENNAN F.M., WILLIAMS R.O., CHU C.Q., PALEOLOG E., CHARLES P.J., TAYLOR P.C., FELDMANN M. Monoclonal anti-TNFα antibody as a probe of pathogenesis and therapy of rheumatoid disease. Immunol. Rev. 1995;144:195–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARLEAU S., FRUTEAU B., SANCHEZ A.B., POUBELLE P.E., BORGEAT P. Role of 5-lipoxygenase products in the local accumulation of neutrophils in dermal inflammation in the rabbit. J. Immunol. 1999;163:3349–3458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCOLL S.R., CLARK-LEWIS I. Inhibition of murine neutrophil recruitment in vivo by CXC chemokine receptor antagonists. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2829–2835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIOTLA J.M., JEFFERY P.K., HELLEWELL P.G. Platelet-activating factor plays a pivotal role in the induction of experimental lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1998;18:197–204. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.2.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MYERS A.K., ROBEY J.W., PRICE R.M. Relationships between tumour necrosis factor, eicosanoids and platelet-activating factor as mediators of endotoxin-induced shock in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;99:499–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASSAR G.M., MONTERO A., FUKUNAGA M., BADR K.F. Contrasting effects of proinflammatory and T-helper lymphocyte subset-2 cytokines on the 5-lipoxygenase pathway in monocytes. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1520–1528. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHAN C., SPORN M. Cytokines in context. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:981–986. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOURSHARGH S., LARKIN S.W., DAS A., WILLIAMS T.J. Interleukin-1-induced leukocyte extravasation across rat mesenteric microvessels is mediated by platelet-activating factor. Blood. 1995;85:2553–2558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOURSHARGH S., RAMPART M., HELLEWELL P.G., JOSE P.J., HARLAN J.M., EDWARDS A.J., WILLIAMS T.J. Accumulation of 111In-neutrophils in rabbit skin in allergic and non-allergic inflammatory reactions in vivo. Inhibition by neutrophil pretreatment in vitro with a monoclonal antibody recognizing the CD18 antigen. J. Immunol. 1989;142:3193–3198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OPPENHEIMER-MARKS N., DAVIS L.S., BOGUE D.T., RAMBERG J., LIPSKY P.E. Differential utilization of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 during the adhesion and transendothelial migration of human T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1991;147:2913–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSBORN L., HESSION C., TIZARD R., VASSALLO C., LUHOWSKYJ S., CHI-ROSSO G., LOBB R. Direct expression cloning of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, a cytokine-induced endothelial protein that binds to lymphocytes. Cell. 1989;59:1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERRETTI M., FLOWER R.J. Cytokines, glucocorticoids and lipocortins in the control of neutrophil migration. Pharmacol. Res. 1994;30:53–59. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(94)80087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POBER J.S., GIMBRONE M.A., JR, LAPIERRE L.A., MENDRICK D.L., FIERS W., ROTHLEIN R., SPRINGER T.A. Overlapping patterns of activation of human endothelial cells by interleukin 1, tumor necrosis factor, and immune interferon. J. Immunol. 1986;137:1893–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PONS F., ROSSI A.G., NORMAN K.E., WILLIAMS T.J., NOURSHARGH S. Role of platelet-activating factor (PAF) in platelet accumulation in rabbit skin: effect of the novel long-acting PAF antagonist, UK-74,505. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:234–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMPART M., DE SMET W., FIERS W., HERMAN A.G. Inflammatory properties of recombinant tumor necrosis factor in rabbit skin in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1989a;169:2227–2232. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMPART M., FIERS W., DE SMET W., HERMAN A.G. Different pro-inflammatory profiles of interleukin 1 (IL 1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in an in vivo model of inflammation. Agents Actions. 1989b;26:186–188. doi: 10.1007/BF02126603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMPART M., WILLIAMS T.J. Evidence that neutrophil accumulation induced by interleukin-1 requires both local protein biosynthesis and neutrophil CD18 antigen expression in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;94:1143–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSS R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANZ M.J., HARTNELL A., CHISHOLM P., WILLIAMS C., DAVIES D., WEG V.B., FELDMANN M., BOLANOWSKI M.A., LOBB R.R., NOURSHARGH S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced eosinophil accumulation in rat skin is dependent on alpha4 integrin/vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 adhesion pathways. Blood. 1997;90:4144–4152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANZ M.J., WEG V.B., BOLANOWSKI M.A., NOURSHARGH S. IL-1 is a potent inducer of eosinophil accumulation in rat skin. Inhibition of response by a platelet-activating factor antagonist and an anti-human IL-8 antibody. J. Immunol. 1995;154:1364–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFF M.H. Role of interleukin 1 and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the mediation of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000;59:i103–i108. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.suppl_1.i103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWEMMER M., AHO H., MICHEL J.-B. Interleukin-1β-induced type IIA secreted phospholipase A2 gene expression and extracellular activity in rat vascular endothelial cells. Tissue Cell. 2001;33:233–240. doi: 10.1054/tice.2000.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHOWELL H.J., BRESLOW R., CONKLYN M.J., HINGORANI G.P., KOCH K. Characterization of the pharmacological profile of the potent LTB4 antagonist CP-105,696 on murine LTB4 receptors in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1127–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRIETER R.M., KUNKEL S.L., SHOWELL H.J., REMICK D.G., PHAN S.H., WARD P.A., MARKS R.M. Endothelial cell gene expression of a neutrophil chemotactic factor by TNFα, LPS, and IL-1β. Science. 1989;243:1467–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.2648570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI T., HATO F., YAMANE T., FUKUMASU H., SUZUKI K., OGITA S., NISHIZAWA Y., KITAGAWA S. Activation of human neutrophil by cytokine-activated endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 2001;88:422–429. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON R.D., NOBLE K.E., LARBI K.Y., DEWAR A., DUNCAN G.S., MAK T.W., NOURSHARGH S. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1)-deficient mice demonstrate a transient and cytokine-specific role for PECAM-1 in leukocyte migration through the perivascular basement membrane. Blood. 2001;97:1854–1860. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORLACIUS H., VOLLMAR B., GUO Y., MAK T.W., PFREUNDSCHUH M.M., MENGER M.D., SCHMITS R. Lymphocyte function antigen 1 (LFA-1) mediates early tumour necrosis factor α-induced leukocyte adhesion in venules. Br. J. Haematol. 2000;110:424–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN OVERVELD F.J., JORENS P.G., RAMPART M., DE BACKER W., VERMEIRE P.A. Tumour necrosis factor stimulates human skin mast cells to release histamine and tryptase. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1991;21:711–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1991.tb03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]