Abstract

The present study was designed to evaluate the nature of intervening agents in L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced neurotoxicity in Neuro-2A cells.

In the absence of cells and in conditions of light protection, at 37°C, L-DOPA or dopamine (1 mM) in culture medium degraded spontaneously in a time-dependent manner, this being prevented by ascorbic acid (200 μM) and other antioxidants, namely glutathione (1 mM), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (1 mM), sodium metabisulphite (200 μM), but not N-ter-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (1 mM) and deferoxamine (100 μM).

The viability of Neuro-2A cells declined following treatment with L-DOPA or dopamine in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. The decrease in cell viability by L-DOPA (10±4% of control) or dopamine (15±4% of control) was markedly attenuated by antioxidants (ascorbic acid, glutathione, N-acetyl-L-cysteine and sodium metabisulphite). Autoxidation of L-DOPA or dopamine was accompanied by the formation of H2O2 in a time-dependent manner, this being completely prevented by ascorbic acid at 24 h or markedly reduced at 48 h.

Protective effects of 100 U ml−1 catalase (40±1% of control) against L-DOPA-induced cell death were lower than those conferred by 200 μM ascorbic acid (70±3% of control). Catalase-induced protection (59±5% of control) against dopamine-induced cell death was similar to that conferred by 200 μM ascorbic acid (57±4% of control). L-DOPA-induced neuronal cell death was also accompanied by increases in caspase-3 activity, this being insensitive to ascorbic acid. Dopamine-induced increase in caspase-3 activity occurred only when autoxidation of the amine was prevented by ascorbic acid.

It is suggested that in addition to generation of H2O2 and quinone formation, L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced cell death may result from induction of apoptosis, as evidenced by increases in caspase-3 activity. Dopamine per se induces apoptosis by a mechanism independent of oxidative stress, as evidenced by the fact that increases in caspase-3 activity occurred only when autoxidation of the amine was prevented.

Keywords: Autoxidation, dopamine, Parkinson's disease, neurotoxicity, neuroprotection, H2O2, antioxidants, caspase-3

Introduction

Parkinson's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized mainly at the cellular level by degeneration of dopamine containing neurones with origin in the substantia nigra (Forno, 1982). At present, the real cause of the degeneration and death of neurones in Parkinsonism is unknown, but evidence suggests that oxidative stress may be involved (Beal, 1995; Fahn & Cohen, 1992; Foley & Riederer, 2000). One source of oxidative stress that is unique to dopaminergic neurones is the presence of dopamine. Metabolism of dopamine via monoamine oxidase (MAO) or amine autoxidation can give rise to radical species, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), semiquinones, and quinones (Graham, 1978). L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), the precursor of dopamine in catecholaminergic neurones, is the most effective therapeutic agent for Parkinson's disease (Lloyd et al., 1975). However, the effectiveness of L-DOPA therapy declines on continuous use, this being accompanied by dyskinesia and on-off phenomena (Obeso et al., 2000). Another potential problem with the use of L-DOPA in treatment of Parkinson's disease arises from the fact that L-DOPA metabolism or autoxidation can give rise to radical species, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), semiquinones, and quinones (Graham, 1978). The quinones generated are thought to mediate toxicity by covalent binding to nucleophilic groups of biological macromolecules (Rotman et al., 1976). The H2O2 resulting from the metabolism or autoxidation of L-DOPA and dopamine can be easily reduced in the presence of ferrous iron (Fe2+) through the Fenton reaction originating the hydroxyl radical (HO•), which is considered the most damaging free radical for living cells. This may be of particular importance in Parkinson's disease, due to the fact that iron is increased in the substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease (Dexter et al., 1989; Griffiths et al., 1999; Riederer et al., 1989; Sofic et al., 1988).

Recently, it has been postulated that during the preclinical phase of Parkinson's disease the turnover rate of dopamine may increase to compensate the loss of dopamine containing neurones (Foley & Riederer, 2000; Lai & Yu, 1997; Schulz et al., 2000; Spina & Cohen, 1989). This increase in the rate of dopamine utilization is likely to accelerate the neurodegenerative process through the generation of quinones, semiquinones and H2O2, resulting from the oxidative metabolism of dopamine (Graham, 1978). Apoptosis may also have an important role in neuronal death induced by dopamine, because many of the chemical and physical treatments capable of inducing apoptosis are also known to induce oxidative stress. Recently, caspase-3, an effector enzyme in programmed cell death, was associated with Parkinson's disease on a post-mortem human brain study (Hartmann et al., 2000). However, the apoptotic degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurones in Parkinson's disease is still a controversial issue.

The aim of the present study was to define the neurotoxicity profile of L-DOPA and dopamine and evaluate the nature of intervening agents, namely quinones, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Neuro-2A cells, a cell line with origin in a mouse neuroblastoma that has been used as an in vitro neuronal model, was thought adequate for this type of study. In fact, Neuro-2A cells, similarly to human neuroblastoma (SK-N-MC) cells and cultures of foetal rat mesencephalon, were found sensitive to the neurotoxic effects of L-DOPA (Han et al., 1996). The mechanisms responsible for L-DOPA-induced toxicity appear to be partially dependent on the autoxidation of L-DOPA (Han et al., 1996). However, Neuro-2A cells were found to be less susceptible to exposure of H2O2 than PC12 cells, due to higher intracellular levels of antioxidant defense factors (Calderon et al., 1999). The third type of reason to use Neuro-2 cells is concerned with the fact they are endowed with the L-type amino acid transporter for the uptake of L-DOPA, similarly to that occurring in rat brain capillary endothelial cells and rat type 1 astrocytes (Sampaio-Maia et al., 2001). It is reported that in addition to generation of H2O2 and quinone formation, L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced cell death may result from induction of apoptosis, as evidenced by increases in caspase-3 activity. Dopamine per se induces apoptosis by a mechanism independent of oxidative stress, as evidenced by the fact that increases in caspase-3 activity occurred only when autoxidation of the amine was prevented by ascorbic acid.

Methods

Cell culture

Neuro-2A cells (CCL-131; passages 170–181) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.) and maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air at 37°C. Neuro-2A cells were grown in Minimum Essential Medium (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) supplemented with 1.5 g l−1 sodium bicarbonate (Sigma) and 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 10% foetal bovine serum (Sigma), 100 U ml−1 penicillin G, 0.25 μg ml−1 amphotericin B, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Sigma) and 25 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanosulphonic acid (HEPES; Sigma). The cell medium was changed every 2 days, and the cells reached confluence after 3–4 days of initial seeding. For subculture, the cells were dissociated with 0.05% tripsin-EDTA, split 1 : 5 and subculture in Costar Petri dishes with 21 cm2 growth area (Costar, Badhoevedorp, The Netherlands). All the test compounds were dissolved in Minimum Essential Medium, and the incubation was serum-free medium. For the measurement of cell viability, quantification of H2O2 and caspase-3 activity, the cells were seeded in 96 or six wells plastic culture clusters (Costar), respectively. Experiments were generally performed 2–3 days after cells reached confluence and 5–7 days after the initial seeding and each cm2 contained about 2×105 cells.

Measurement of L-DOPA and dopamine

Autoxidation was followed by disappearance of L-DOPA and dopamine. L-DOPA and dopamine working solutions were prepared in serum-free medium and stored in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air at 37°C. L-DOPA and dopamine were quantified by means of high pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection, as previously reported (Soares-Da-silva et al., 1994). The high pressure liquid chromatography system consisted of a pump (Gilson model 302; Gilson Medical Electronics, Villiers le Bel, France) connected to a manometric module (Gilson model 802 C) and a stainless-steel 5 μm ODS column (Biophase; Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN, U.S.A.) of 25 cm length; samples were injected by means of an automatic sample injector (Gilson model 231) connected to a Gilson dilutor (model 401). The mobile phase was a degassed solution of citric acid (0.1 mM), sodium octylsulphate (0.5 mM), sodium acetate (0.1 M), EDTA (0.17 mM), dibutylamine (1 mM) and methanol (8% v v−1), adjusted to pH 3.5 with perchloric acid (2 M) and pumped at a rate of 1.0 ml min−1. The detection was carried out electrochemically with a glassy carbon electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and an amperometric detector (Gilson model 141); the detector cell was operated at 0.75 V. The current produced was monitored using the Gilson 712 HPLC software. The lower limits for detection of L-DOPA and dopamine ranged from 350 to 500 fmol.

Measurement of cell viability

Cell viability was measured using calcein-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). The membrane permeant calcein-AM, a nonfluorescent dye, is taken up and converted by intracellular esterases to membrane impermeant calcein, which emits green fluorescence. After treatment, cells were washed twice with Hanks' medium (medium composition, in mM: NaCl 137, KCl 5, MgSO4 0.8, Na2HPO4 0.33, KH2PO4 0.44, CaCl2 0.25; MgCl2 1.0, Tris HCl 0.15 and sodium butyrate 1.0, pH=7.4) and loaded with 2 μM calcein-AM in Hanks medium, at room temperature for 30 min. Fluorescence was measured at 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emission wavelengths in a multiplate reader (Spectromax Gemini, Molecular Devices). To determine minimum staining for calcein-AM (calceinmin), six wells were treated with ethanol 15 min before calcein-AM addition. The per cent viability was then calculated as [(calceinSsample–calceinmin)/(calceincontrol–calceinmin)]×100.

Measurement of H2O2

H2O2 was measured fluorometrically using the Amplex™ Red Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). Amplex™ Red is a fluorogenic substrate with very low background fluorescence that reacts with H2O2 with a 1 : 1 stoichiometry to produce a highly fluorescent reagent (Mohanty et al., 1997). Measurement of H2O2 accumulation was followed both in extracellular medium, during treatment with drugs, and in dopamine solutions, during autoxidation. Fluorescence intensity was measured in multiplate reader (Spectromax Gemini, Molecular Devices) at an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm at room temperature. After subtracting background fluorescence, the concentration of H2O2 was calculated using a resorufin-H2O2 standard calibration curve generated from experiments using H2O2 and Amplex™ Red.

Caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was measured fluorometrically using the Caspase-3 Assay Kit #2 (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). After treatment, the growth medium was aspirated and the cells washed with Hanks medium and scraped from the six well plastic culture clusters (Costar). The cells were centrifuged (1300 r.p.m., 5 min, 4°C), and the resultant pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) and incubated on ice for 30 min. To pellet the cellular debris, the lysed cells were centrifuged at 5000 r.p.m. for 5 min. Thereafter, 50 μl of supernatant from each sample was transferred to individual microplate wells and incubated with the fluorogenic substrate rhodamine 110 bis-(N-CBZ-L-aspartyl-L-glutamyl-L-valyl-L-aspartic acid amide) (Z-DEVD-R110) (25 μM) at room temperature. Substrate cleavage and rhodamine 110 accumulation was followed fluorometrically with excitation at 496 nm and emission at 520 nm in a multiplate reader (Spectromax Gemini, Molecular Devices). Protein determination was performed by the method of Bradford (1976), with human serum albumin as a standard.

Data analysis

Arithmetic means are given with s.e.mean or geometric means with 95% confidence values. Statistical analysis was done by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons. A P value less than 0.05 was assumed to denote a significant difference.

Drugs

Ascorbic acid, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, N-t-butyl-α-phenyl-nitrone, catalase from bovine liver, deferoxamine mesylate, dopamine hydrochloride, glutathione, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, pargyline and sodium metabisulphite, were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Calcein-AM was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, U.S.A.).

Results

L-DOPA and dopamine autoxidation

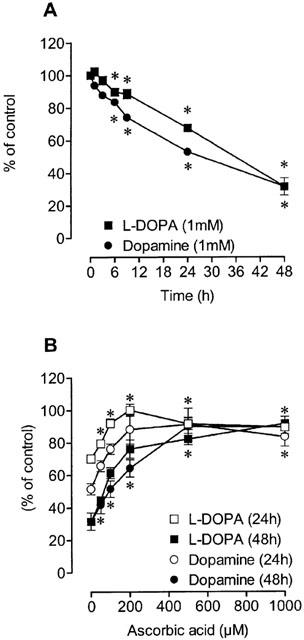

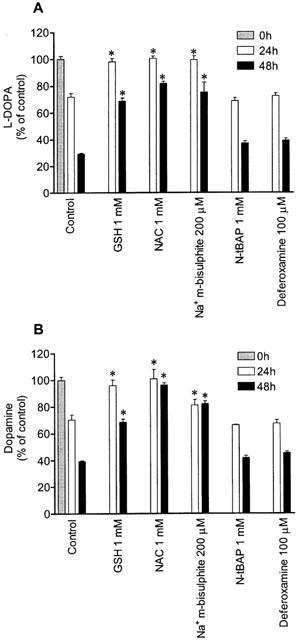

The autoxidation of L-DOPA and dopamine occurred spontaneously in the presence of O2 and was followed as the disappearance of L-DOPA or dopamine in solution. When 1 mM L-DOPA or dopamine working solution were incubated for 1 to 48 h in serum-free medium, the amounts of L-DOPA or dopamine decreased in a time-dependent manner (Figure 1a). After 24 and 48 h of incubation the amounts of L-DOPA were 67±2% and 32±1% of the initial concentration, respectively. After 24 or 48 h of incubation the amounts of dopamine were 53±1% and 32±5% of the initial concentration, respectively. The addition of ascorbic acid prevented the disappearance of L-DOPA or dopamine in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1b). When L-DOPA or dopamine were incubated in the presence of 200 μM ascorbic acid, the amounts of L-DOPA and dopamine after 24 h of incubation were, respectively, 100±4% and 88±9% of the initial concentration. A similar picture was observed after 48 h incubation in the presence of 200 μM ascorbic acid. The antioxidants glutathione (1 mM), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (1 mM), sodium metabisulphite (200 μM) partially prevented the autoxidation of dopamine, but the strong iron chelator deferoxamine (100 μM) and the free radical scavenger N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (1 mM) did not affect the autoxidation process (Figure 2). According to Basma et al. (1995), the in vitro autoxidation of L-DOPA generates quinones that give an orange-brown colour to incubation medium. During L-DOPA and dopamine autoxidation the orange-brown colour was also observed. In the presence of antioxidants this orange-brown colour was attenuated or abolished (data not shown). These findings strongly suggest that L-DOPA quinones and dopamine quinones may have been generated during autoxidation of these two catechol derivatives.

Figure 1.

The autoxidation of L-DOPA and dopamine was followed by h.p.l.c. with electrochemical detection in the (A) absence or in the (B) presence of different concentrations (50–1000 μM) of ascorbic acid (AA). Each symbol or column represents the mean of 3–16 experiments per group; vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 2.

Effect glutathione (GSH), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), sodium metabisulphite (Na+ m-bisulphite), N-ter-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (N-tBAP) and deferoxamine on autoxidation of (A) 1 mM L-DOPA and (B) 1 mM dopamine working solutions for 24 and 48 h. Each column represents the mean of four experiments per group; vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control.

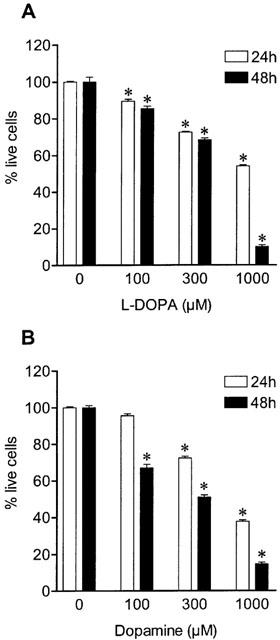

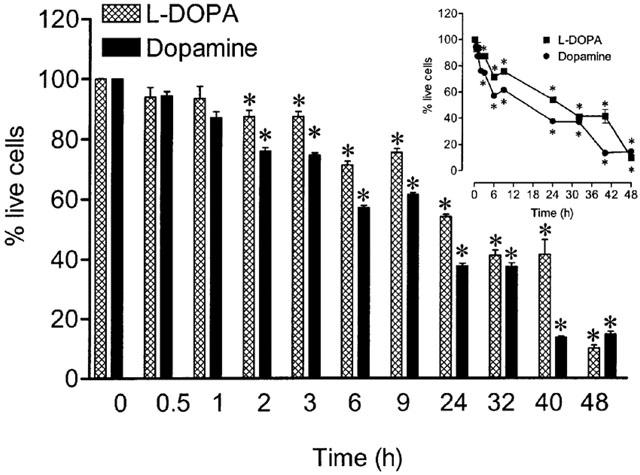

L-DOPA and dopamine citotoxicity

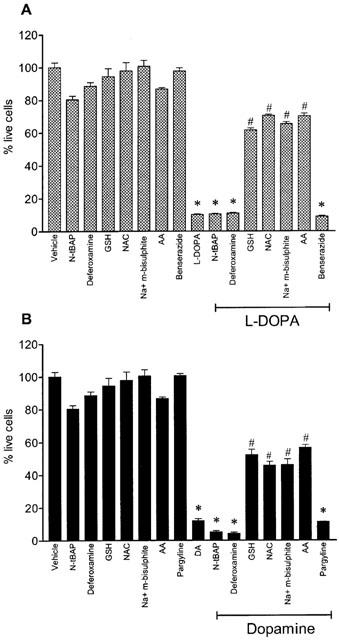

As shown in Figure 3, exposure of Neuro-2A cells to L-DOPA or dopamine (100–1000 μM) for 24 and 48 h reduced cell viability in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Figure 4 shows the time-dependent decrease in cell viability by L-DOPA or dopamine. After 48 h of incubation with 1 mM L-DOPA or 1 mM dopamine, viability of cells treated with L-DOPA and dopamine was, respectively, 10±4% and 15±4%, when compared to vehicle. The effects of ascorbic acid, glutathione, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, sodium metabisulphite, deferoxamine and N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone on L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced decrease in cell viability were examined after 48 h of incubation (Figure 5). In this set of experiments it was decided to use the most adverse conditions for the cells, which was found to be a 48 h exposure to 1 mM of either L-DOPA or dopamine. Ascorbic acid, glutathione, sodium metabisulphite, and N-acetyl-L-cysteine partially prevented the L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced decrease in cell viability by 50 to 59% and 34 to 44%, respectively. However, the free radical scavenger N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone and the strong iron chelator deferoxamine did not protect cells against L-DOPA- or dopamine-induced decrease in cell viability. The aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor benserazide (10 μM) and the MAO inhibitor pargyline (100 μM) failed to prevent cell death induced by 1 mM L-DOPA and 1 mM dopamine, respectively, after 48 h of incubation (Figure 5). The reduction in cell viability observed with N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone or ascorbic acid alone did not attain statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependent effect of (A) L-DOPA and (B) dopamine on cell viability for 24 and 48 h. Each column represents the mean of 6–18 experiments per group; vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 4.

Time dependence of cell viability during exposure to 1 mM L-DOPA or 1 mM dopamine. The inset shows the time-course in a real time scale. Each column or symbol represents the mean of 6–8 experiments per group; vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 5.

Effect of N-ter-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (N-tBAP, 1 mM), deferoxamine (100 μM), glutathione (GSH, 1 mM), N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC, 1 mM), sodium metabisulphite (Na+ m-bisulphite, 200 μM), benserazide (10 μM), pargyline (100 μM) and ascorbic acid (AA, 200 μM), on cell death induced by (A) 1 mM L-DOPA and (B) 1 mM dopamine. Each column represents the mean of 4–6 experiments per group; vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.01 compared with control; and #P<0.01 compared with L-DOPA alone or DA alone.

H2O2 generation

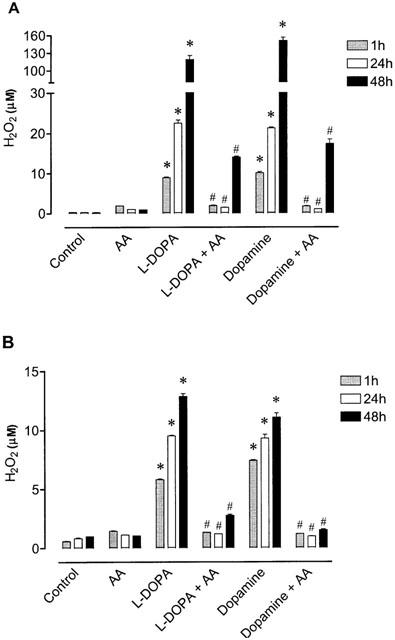

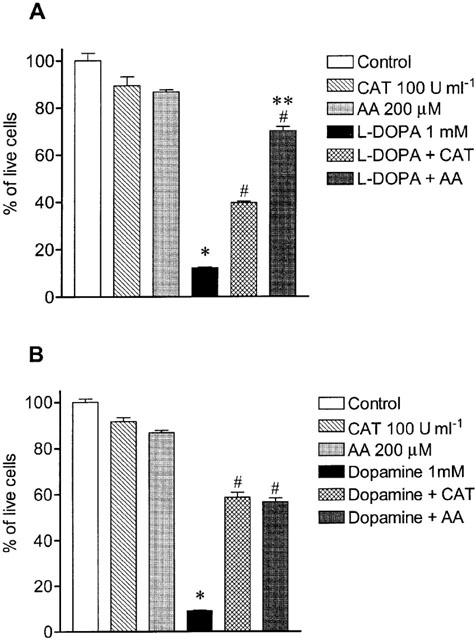

Exposure of cultured cells to L-DOPA or dopamine is associated with H2O2 production generated during dopamine metabolism or autoxidation. To elucidate whether L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced decrease in cell viability involved H2O2 production, we followed (1–48 h) the appearance of this toxic specie in L-DOPA and dopamine working solutions and in the extracellular medium. As shown in Figure 6a, autoxidation of L-DOPA and dopamine in working solutions was accompanied by the generation of H2O2 in a time-dependent manner. The levels of H2O2 during autoxidation of 1 mM L-DOPA and 1 mM dopamine at 48 h were 6 fold those at 24 h. The presence of 200 μM ascorbic acid markedly prevented the generation of H2O2 during autoxidation of both L-DOPA and dopamine at all time points (1, 24 and 48 h; Figure 6a). The exposure of Neuro-2A cells to L-DOPA or dopamine also resulted in a time-dependent increase in H2O2 levels in the extracellular medium (Figure 6b). As observed with L-DOPA and dopamine working solutions, levels of H2O2 in the extracellular medium of cells treated with L-DOPA or dopamine was markedly attenuated in the presence of 200 μM ascorbic acid (Figure 6b). It is interesting to observe, however, that levels of H2O2 in L-DOPA and dopamine working solutions were greater than in the extracellular medium, this being particularly evident at 48 h (Figure 6a,b). This observation may suggest that cells may be endowed with a mechanism to degrade H2O2. Following this rationale and to confirm the involvement of H2O2 as a casual agent in L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced cell death, it was decided to evaluate the effect of an effective concentration of catalase (Lai & Yu, 1997). As shown in Figure 7, catalase partially prevented the toxicity induced by 1 mM L-DOPA (39% cell viability) during a 48 h period. However, this protective effect of catalase was markedly lower than that obtained with ascorbic acid (70% cell viability). In contrast, catalase and ascorbic acid were equipotent (respectively, 59 and 57% cell viability) in preventing dopamine-induced cell death (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Levels of H2O2 in the absence and in the presence of ascorbic acid (AA, 200 μM) during (A) autoxidation working solutions of 1 mM L-DOPA or 1 mM dopamine and (B) extracellular medium during treatment with 1 mM L-DOPA or 1 mM dopamine. Each column represents the mean of 3–6 experiments per group and vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control; and #P<0.05 compared with L-DOPA alone or DA alone.

Figure 7.

Effect of catalase (CAT, 100 U ml−1) and ascorbic acid (AA, 200 μM) on cell death induced by (A) 1 mM L-DOPA and (B) 1 mM dopamine. Each column represents the mean of 6–11 experiments per group and vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control; #P<0.05 compared with L-DOPA alone or DA alone; and **P<0.05 compared with L-DOPA+CAT.

Caspase-3 activity

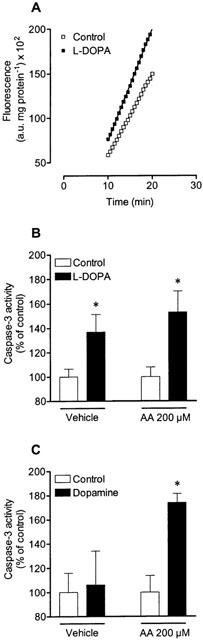

To investigate whether the cellular damage induced by L-DOPA and dopamine was accompanied by apoptosis it was thought worthwhile to measure caspase-3 activity. For this purpose, Neuro-2A cells were treated for 9 h with 1 mM L-DOPA or 1 mM dopamine alone or in the presence of 200 μM ascorbic acid. Figure 8a shows the cleavage of fluorogenic substrate during the linear phase (from 10 to 20 min) in vehicle- and L-DOPA-treated cells. As shown in Figure 8b, L-DOPA increased caspase-3 activity, this being insensitive to ascorbic acid. On the other hand, dopamine-induced increase in caspase-3 activity occurred only when autoxidation of the amine was prevented by ascorbic acid (Figure 8c).

Figure 8.

Fluorescence of specific caspase-3 substrate cleavage after treatment (9 h) with drugs. (A) represents the linear phase, used for determination of caspase-3 activity, of caspase-3 substrate cleavage in vehicle- and L-DOPA-treated cells. Effect of (B) 1 mM L-DOPA and (C) 1 mM dopamine in absence or in presence of 200 μM ascorbic acid (AA) on caspase-3 activity. Each symbol or column represents the mean of three experiments per group and vertical lines show s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control.

Discussion

The present study was designed to evaluate the extent and magnitude of L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced neurotoxicity and the importance of L-DOPA and dopamine autoxidation in neuronal cell death. The data gathered here indicates that in addition to generation of H2O2 and quinone formation, L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced cell death may result from induction of apoptosis, as evidenced by increases in caspase-3 activity. The finding that increases in caspase-3 activity by dopamine occurred only when autoxidation of the amine was prevented by ascorbic acid, strongly suggests that dopamine per se induces toxicity by a mechanism independent of oxidative stress. The finding that dopamine promotes apoptosis in the presence of antioxidants would explain why antioxidants fail to protect against cell death of dopaminergic neurones in vivo.

The results reported here indicate the occurrence of a rapid process of L-DOPA and dopamine autoxidation under physiological conditions of pH and temperature, in agreement with previous work in this field (Graham, 1978; Zhang & Dryhurst, 1994). The prevention of L-DOPA or dopamine degradation in solution by antioxidants, namely ascorbic acid, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, glutathione and sodium metabisulphite, but not by deferoxamine, a strong iron chelator, and N-tert-butyl-α-phenyl-nitrone, a free radical scavenger, strongly suggests the presence of an oxidative process. Autoxation of L-DOPA and dopamine was also accompanied by the formation of H2O2 in a time-dependent manner. In the presence of ascorbic acid, the generation of H2O2 during L-DOPA and dopamine autoxidation was completely prevented at 24 h or markedly reduced at 48 h.

The exposure of Neuro-2A cells to L-DOPA or dopamine was accompanied in a time- and concentration-dependent manner by a decline in cell viability. After 48 h of incubation with 1 mM L-DOPA or 1 mM dopamine cell viability was drastically reduced to 10 and 15% of control. In the presence of antioxidants, namely, ascorbic acid, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, glutathione and sodium metabisulphite, the decrease in cell viability induced by L-DOPA or dopamine was partially attenuated (by 50 to 59% and by 34 to 44%, respectively). These findings agree the view that mechanisms of L-DOPA and dopamine neurotoxicity may be partially related to the formation of quinones and reactive oxygen intermediates during L-DOPA or dopamine autoxidation. Furthermore, treatment of Neuro-2A cells with L-DOPA or dopamine resulted in the accumulation of H2O2 in the extracellular medium. The concentration of H2O2 in the extracellular medium was drastically reduced when cells were cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid. Taken together, the decrease in H2O2 levels in the extracellular medium and the increase in cell viability by ascorbic acid, strongly suggest that the generation of H2O2 may be of importance in L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced neurotoxicity. This view was confirmed by the finding that catalase, which promotes the conversion of H2O2 to H2O and O2, markedly attenuated the toxicity induced by L-DOPA and dopamine. Though this would agree with the involvement of H2O2 in cell death it also constitutes evidence against a major role of quinones in L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced cell death. In fact, removal of H2O2 by catalase should not affect the formation or disposition of L-DOPA quinones or dopamine quinones. In this respect it is interesting to note that the effect of catalase against L-DOPA-induced cell death markedly differed from that against dopamine-induced cell death. The effect of catalase against L-DOPA-induced cell death was half that obtained with the antioxidants, whereas catalase and antioxidants conferred similar protection against dopamine-induced cell death. This favours the view of a more pronounced involvement of L-DOPA quinones than dopamine quinones in cell death induced by L-DOPA and dopamine, respectively. On the other hand, the finding that protection conferred by antioxidants or catalase against dopamine-induced neuronal death was not greater than 50%, suggests the involvement of non-oxidative mechanisms in dopamine-induced toxicity. This observation is in agreement with a recent study showing a non-oxidative mechanism of dopamine cytotoxicity mediated by NF-κB activation (Weingarten et al., 2001). In line with this view are the findings showing that dopamine-induced cell death may arise from induction of apoptosis. In fact, when autoxidation of dopamine was prevented by ascorbic acid, dopamine markedly increased caspase-3 activity in Neuro-2A cells. This is in agreement with the view that dopamine per se induces toxicity by a mechanism independent of oxidative stress and suggests the involvement of apoptosis in dopamine-induced cell death through a non-oxidative mechanism. On the other hand, in the absence of ascorbic acid, when autoxidation of dopamine is facilitated, dopamine failed to alter caspase-3 activity. This contrasted with that observed with L-DOPA in that L-DOPA-induced cell death was also accompanied by increases in caspase-3 activity, this being insensitive to ascorbic acid. This suggests that dopamine-induced apoptosis occurs mainly through a non-oxidative mechanism. The findings that both L-DOPA and dopamine may promote apoptosis would explain why antioxidants fail to protect against cell death of dopaminergic neurones in vivo.

Because L-DOPA can be readily converted to dopamine in the presence of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, it could be hypothesized that dopamine may have exerted toxic effects in cells treated with L-DOPA. On the other hand, toxic effects of dopamine may result via either oxidative deamination by MAO or autoxidation (Graham, 1978; Michel & Hefti, 1990; Rosenberg, 1988). The finding that benserazide, which prevents the conversion of L-DOPA to dopamine, failed to affect L-DOPA toxicity, indicates that the autoxidation of dopamine was not important in L-DOPA-induced cell death. This is in agreement with previous studies (Basma et al., 1995; Walkinshaw & Waters, 1995) while showing that the mechanism of L-DOPA toxicity in PC12 cells arises from L-DOPA autoxidation rather than from enzymatic oxidative metabolism or autoxidation of dopamine formed from L-DOPA. The finding that pargyline, which prevents dopamine deamination, failed to affect dopamine toxicity indicates that the oxidative metabolism of dopamine may not be important in dopamine-induced cell death in Neuro-2A cells. This is in agreement with the findings that dopamine toxicity under in vitro (SH-SY5Y cells) or in vivo (Rat) experimental conditions arises from dopamine autoxidation rather than from enzymatic oxidative metabolism of dopamine (Ben-Shachar et al., 1995; Lai & Yu, 1997). The findings that the iron chelator deferoxamine and the hydroxyl free radical scavenger N-tert-butyl-α-phenyl-nitrone failed to protect Neuro-2A cells against the cytotoxic effects of L-DOPA and dopamine is in agreement with previous studies (Lai & Yu, 1997). However, others have reported that deferoxamine prevented the toxicity induced by iron in vitro and in vivo studies (Ben-Shachar et al., 1991; Okuda et al., 1996; Tanaka et al., 1991). One explanation that can be put forward is concerned with the extremely short (10−9 s) half-life of the hydroxyl radical (Pryor, 1986; Sies, 1991). Since availability of iron was vestigial, it is suggested that the hydroxyl radical and the Fenton reaction may be not involved in L-DOPA- or dopamine-induced toxicity of Neuro-2A cells. By contrast, in Parkinson's disease, due to the fact that iron is increased in the substantia nigra (Dexter et al., 1989; Griffiths et al., 1999; Riederer et al., 1989; Sofic et al., 1988), the H2O2 resulting from autoxidation of dopamine and L-DOPA can easily be reduced through the Fenton reaction to give the hydroxyl radical (HO•). These toxic species, i.e., H2O2 and HO•, have been reported to attack DNA (Brawn & Fridovich, 1981), membrane lipids (Minotti & Aust, 1987), and other essential cell components (Oliver et al., 1990).

In conclusion, the findings reported here support the view that in addition to generation of H2O2 and quinone formation, L-DOPA- and dopamine-induced cell death may result from induction of apoptosis, as evidenced by increases in caspase-3 activity. The finding that increases in caspase-3 activity by dopamine occurred only when autoxidation of the amine was prevented by ascorbic acid, strongly suggest that dopamine per se induces toxicity by a mechanism independent of oxidative stress. Finally, dopamine-induced cell death, in comparison with that by L-DOPA, may be considered a more complex and serious event since it involves mainly apoptosis through non-oxidative mechanisms for which a therapeutic intervention has not yet been envisioned.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia for fellowship POCTI 35747/2000 (R Pedrosa).

Abbreviations

- L-DOPA

L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

References

- BASMA A.N., MORRIS E.J., NICKLAS W.J., GELLER H.M. L-dopa cytotoxicity to PC12 cells in culture is via its autoxidation. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:825–832. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64020825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAL M.F. Aging, energy, and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Ann. Neurol. 1995;38:357–366. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEN-SHACHAR D., ESHEL G., FINBERG J.P., YOUDIN M.B. The iron chelator desferrioxamine (Desferal) retards 6-hydroxydopamine-induced degeneration of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons. J. Neurochem. 1991;56:1441–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb11444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEN-SHACHAR D., ZUK R., GLINKA Y. Dopamine neurotoxicity: inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:718–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64020718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADFORD M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAWN K., FRIDOVICH I. DNA strand scission by enzymatically generated oxygen radicals. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1981;206:414–419. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALDERON F.H., BONNEFONT A., MUNOZ F.J., FERNANDEZ V., VIDELA L.A., INESTROSA N.C. PC12 and neuro 2a cells have different susceptibilities to acetylcholinesterase-amyloid complexes, amyloid25-35 fragment, glutamate, and hydrogen peroxide. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;56:620–631. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990615)56:6<620::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEXTER D.T., WELLS F.R., LEES A.J., AGID F., AGID Y., JENNER P., MARSDEN C.D. Increased nigral iron content and alterations in other metal ions occurring in brain in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem. 1989;52:1830–1836. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAHN S., COHEN G. The oxidant stress hypothesis in Parkinson's disease: evidence supporting it. Ann. Neurol. 1992;32:804–812. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOLEY P., RIEDERER P. Influence of neurotoxins and oxidative stress on the onset and progression of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. 2000;247 Suppl. 2:82–94. doi: 10.1007/pl00007766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORNO L.S.Pathology of Parkinson's disease Movement Disorders 1982London: Butterworth Scientific; 25–49.ed. Marsden, D. and Fahn, S. pp [Google Scholar]

- GRAHAM D.G. Oxidative pathways for catecholamines in the genesis of neuromelanin and cytotoxic quinones. Mol. Pharmacol. 1978;14:633–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITHS P.D., DOBSON B.R., JONES G.R., CLARKE D.T. Iron in the basal ganglia in Parkinson's disease. An in vitro study using extended X-ray absorption fine structure and cryo-electron microscopy. Brain. 1999;122:667–673. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN S.K., MYTILINEOU C., COHEN G. L-DOPA up-regulates glutathione and protects mesencephalic cultures against oxidative stress. J. Neurochem. 1996;66:501–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66020501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARTMANN A., HUNOT S., MICHEL P.P., MURIEL M.P., VYAS S., FAUCHEUX B.A., MOUATT-PRIGENT A., TURMEL H., SRINIVASAN A., RUBERG M., EVAN G.I., AGID Y., HIRSCH E.C. Caspase-3: A vulnerability factor and final effector in apoptotic death of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:2875–2880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040556597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAI C.T., YU P.H. Dopamine- and L-beta-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine hydrochloride (L-Dopa)- induced cytotoxicity towards catecholaminergic neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Effects of oxidative stress and antioxidative factors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997;53:363–372. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00731-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LLOYD K.G., DAVIDSON L., HORNYKIEWICZ O. The neurochemistry of Parkinson's disease: effect of L-dopa therapy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1975;195:453–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHEL P.P., HEFTI F. Toxicity of 6-hydroxydopamine and dopamine for dopaminergic neurons in culture. J. Neurosci. Res. 1990;26:428–435. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490260405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINOTTI G., AUST S.D. The role of iron in the initiation of lipid peroxidation. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1987;44:191–208. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(87)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHANTY J.G., JAFFE J.S., SCHULMAN E.S., RAIBLE D.G. A highly sensitive fluorescent micro-assay of H2O2 release from activated human leukocytes using a dihydroxyphenoxazine derivative. J. Immunol. Methods. 1997;202:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OBESO J.A., RODRIGUEZ-OROZ M.C., CHANA P., LERA G., RODRIGUEZ M., OLANOW C.W. The evolution and origin of motor complications in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2000;55:S13–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKUDA S., NISHIYAMA N., SAITO H., KATSUKI H. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated neuronal cell death induced by an endogenous neurotoxin, 3-hydroxykynurenine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:12553–12558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLIVER C.N., STARKE-REED P.E., STADTMAN E.R., LIU G.J., CARNEY J.M., FLOYD R.A. Oxidative damage to brain proteins, loss of glutamine synthetase activity, and production of free radicals during ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury to gerbil brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:5144–5147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRYOR W.A. Oxy-radicals and related species: their formation, lifetimes, and reactions. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1986;48:657–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIEDERER P., SOFIC E., RAUSCH W.D., SCHMIDT B., REYNOLDS G.P., JELLINGER K., YOUDIM M.B. Transition metals, ferritin, glutathione, and ascorbic acid in Parkinsonian brains. J. Neurochem. 1989;52:515–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENBERG P.A. Catecholamine toxicity in cerebral cortex in dissociated cell culture. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:2887–2894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02887.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTMAN A., DALY J.W., CREVELING C.R., BREAKEFIELD X.O. Uptake and binding of dopamine and 6-hydroxydopamine in murine neuroblastoma and fibroblast cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1976;25:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(76)90337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPAIO-MAIA B., SERRAO M.P., SOARES-DA-SILVA P. Regulatory pathways and uptake of L-DOPA by capillary cerebral endothelial cells, astrocytes, and neuronal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C333–C342. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.2.C333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULZ J.B., LINDENAU J., SEYFRIED J., DICHGANS J. Glutathione, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:4904–4911. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIES H. Oxidative stress: from basic research to clinical application. Am. J. Med. 1991;91:31S–38S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOARES-DA-SILVA P., FERNANDES M.H., PINTO-DO-O P.C. Cell inward transport of L-DOPA and 3-O-methyl-L-DOPA in rat renal tubules. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:611–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOFIC E., RIEDERER P., HEINSEN H., BECKMANN H., REYNOLDS G.P., HEBENSTREIT G., YOUDIM M.B. Increased iron (III) and total iron content in post mortem substantia nigra of parkinsonian brain. J. Neural. Transm. 1988;74:199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF01244786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPINA M.B., COHEN G. Dopamine turnover and glutathione oxidation: implications for Parkinson disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:1398–1400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA M., SOTOMATSU A., KANAI H., HIRAI S. Dopa and dopamine cause cultured neuronal death in the presence of iron. J. Neurol. Sci. 1991;101:198–203. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(91)90046-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKINSHAW G., WATERS C.M. Induction of apoptosis in catecholaminergic PC12 cells by L-DOPA. Implications for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:2458–2464. doi: 10.1172/JCI117946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEINGARTEN P., BERMAK J., ZHOU Q.Y. Evidence for non-oxidative dopamine cytotoxicity: potent activation of NF-kappa B and lack of protection by anti-oxidants. J. Neurochem. 2001;76:1794–1804. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG F., DRYHURST G. Effects of L-cysteine on the oxidation chemistry of dopamine: new reaction pathways of potential relevance to idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:1084–1098. doi: 10.1021/jm00034a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]