Abstract

Dimemorfan, an antitussive for more than 25 years, has previously been reported to be a relative high-affinity ligand at sigma-1 (σ1) receptor with the Ki value of 151 nM.

To test whether dimemorfan has anti-amnesic effects similar to a σ1 receptor agonist, this study examined its effects on scopolamine- and β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia in mice.

Dimemorfan (10–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) administered 30 min before the training trial, immediately after the training trial, or 30 min before the retention test significantly improved scopolamine (1 mg kg−1, i.p.)- or β-amyloid peptide-(25-35) (3 nmol mouse−1, i.c.v.)-induced amnesia in a step-through passive avoidance test. Dimemorfan (5–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) pretreatment also attenuated scopolamine (8 mg kg−1, i.p.)-induced amnesia in a water-maze test. And, these anti-amnesic effects of dimemorfan, like the putative σ1 receptor agonist (+)-N-allylnormetazocine ((+)-SKF-10047), were antagonized by a σ receptor antagonist haloperidol (0.25 mg kg−1, i.p.).

These results indicated that dimemorfan has anti-amnesic effects and acts like a σ1 receptor agonist.

Keywords: Dimemorfan, anti-amnesic effect, σ1 receptor, scopolamine, β-amyloid peptide-(25-35), step-through passive avoidance, water maze, (+)-SKF-10047, haloperidol

Introduction

Dimemorfan (d-3-methyl-N-methylmorphinan) is an analogue of dextromethorphan and both compounds are non-opioid antitussive drugs safely used in the clinic for more than 25 years (Kase et al., 1976). In addition, dextromethorphan has been shown to have anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects in a variety of experimental models (Tortella & Musacchio, 1986; Choi, 1987; Leander et al., 1988; Steinberg et al., 1993). Our previous study demonstrated that dimemorfan has equipotent anticonvulsant effect as dextromethorphan, but does not produce phencyclidine-like hyperlocomotion exhibited by dextromethorphan in mice (Chou et al., 1999). Furthermore, we demonstrated that dimemorfan has a relative high affinity at sigma-1 (σ1) receptors (Ki=151 nM) vs sigma-2 receptors (Ki=4421 nM) as determined by receptor binding assay on rat brain membranes (Chou et al., 1999).

The σ1 receptors are a subtype of σ receptors known to be widely distributed in the nervous, peripheral, endocrine, and immune systems (Su, 1991; Hanner et al., 1996). Over seven diverse structural classes of pharmacological agents, including morphinans (e.g., dextromethorphan), (+)-benzomorphans (e.g., (+)-N-allylnormetazocine ((+)-SKF-10047)), butyrophenones (e.g., haloperidol) and neurosteroids, can bind σ1 receptors with high affinity. The σ1 receptor has been cloned and its deduced amino acid sequence is 30% identical and 66% similar to a yeast C8-C7 sterol isomerase, but without similar enzymatic activity (Hanner et al., 1996; Prasad et al., 1998). σ1 receptors are ordinarily present in the endoplasmic reticulum, while in the presence of σ1 receptor ligand a part of σ1 receptors translocate to the nuclear membrane and plasma membrane (Morin-Surun et al., 1999; Hayashi et al., 2000). Despite the fact that it is not a GTP-binding protein coupled receptor, some effects at the σ1 receptor are indirectly inhibited by pertussis toxin (Monnet et al., 1994; Hayashi et al., 2000) and activation of this receptor can result in the recruitment of the subsequent, calcium-dependent phospholipase C and protein kinase C cascade (Morin-Surun et al., 1999). Hayashi & Su (2001) reported that σ1 receptor formed a trimeric complex with ankyrin B (a cytoskeletal adaptor protein) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor and σ1 receptor agonists might modulate vesicle transport and neurotransmitter release by regulating the dynamics of ankyrin B. Although the precise physiological function of this receptor is unclear, many preclinical studies have implied that selective σ1 receptor ligands have therapeutic potentials in the treatment of certain disorders of central nervous system including learning and memory impairments (Maurice & Lockhart, 1997; Maurice et al., 1999; 2001).

It is well known that central cholinergic system plays an important role in the learning and memory processes (Smith, 1988). The σ1 receptors appear to play a potent neuromodulatory role on the cholinergic neurotransmission including the enhancement of stimulus-evoked acetylcholine (ACh) release in cerebral and hippocampal slices in vitro (Siniscalchi et al., 1987; Junien et al., 1991) and the increment of the extracellular ACh concentrations in the rat frontal cortex and hippocampus in vivo (Matsuno et al., 1992; 1993a; 1995). Furthermore, several selective σ1 receptor ligands have been reported to have anti-amnesic effects against cholinergic dysfunction-induced memory impairments in rodents, including those induced by muscarinic ACh receptor antagonist scopolamine (Earley et al., 1991; Matsuno et al., 1993b; 1997), nicotinic ACh receptor antagonist mecamylamine (Maurice et al., 1994), choline uptake blocker hemicholinium-3 (Matsuno et al., 1994), the toxic aggregated β-amyloid peptide-(25-35) (Maurice et al., 1998), and the lesions of the basal forebrain (Senda et al., 1996).

Although dimemorfan is a relative high affinity ligand at σ1 receptors, its putative anti-amnesic effect and σ1 receptor agonist properties are unclear. Therefore, this study examined the effects of dimemorfan on scopolamine- and β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia in mice using a step-through passive avoidance test or a water-maze test and compared with those of the selective σ1 ligand (+)-SKF-10047.

Methods

Animals

Male ICR (Institute of Cancer Research) mice (25–30 g) were obtained from the Animal Center of National Taiwan University. They were maintained on a 12-h light and 12-h dark cycle (light on between 0700 and 1900 h) with food and tap water ad libitum.

Drugs and reagents

Dimemorfan phosphate was kindly given by Dr Yueh-Ching Chou as a gift from Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Company Ltd.; (+)-SKF-10047 hydrochloride was purchased from Tocris (Ballwin, U.S.A.); haloperidol (Binin-U® injection) was obtained from Swiss Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tainan, Taiwan); (−)-scopolamine hydrochloride and amyloid β-protein fragment 25-35 (β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Drugs were dissolved in twice-filtered water and administered in a dosage of 0.1 ml per 10 g of body weight.

Step-through passive avoidance test

This experiment was according to our previous established method (Wang et al., 2001). The experimental apparatus for the step-through passive avoidance test is an automated shuttle-box (Cat. 7551 Passive Avoidance Controller and Cat 7553 Passive Avoidance Mouse Cage, UGO Basile, Italy), that is divided into an illuminated compartment and a dark compartment of the same size by a wall with a guillotine door. Each mouse was put through the adaptation trial by placing it gently in the illuminated compartment, facing away from the dark compartment. After 10 s, the door was opened and the mouse moved into the dark compartment freely. When the latency to leave the illuminated compartment was less than 30 s, the mouse was chosen for the training trial 2 h later. The training trial is similar to the adaptation trial except that the door is closed as soon as the mouse steps into the dark compartment and an inescapable foot shock (0.6 mA, 2 s) is delivered through the grid floor (Venault et al., 1986). The responses to the electric shock were observed and scored as follows: 0, no response; 1, flinch (movement of any part of the body); and 2, run (running or jumping) or vocalization (Riekkinen, 1994). The retention test was performed 24 h after the training trial in the similar manner without the electric shock and the step-through latency to the dark compartment was recorded. The maximal cut-off time for step-through latency was 300 s (Venault et al., 1986).

In scopolamine-induced amnesia, scopolamine (1 mg kg−1, i.p.) was administered 20 min prior to the training trial. In β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia, the peptide was dissolved in sterile twice-filtered water and aggregated by incubation at 37°C for 4 days before use. The aggregated form of β-amyloid peptide-(25-35) (3 nmol) was administered i.c.v. using a microsyringe with a 28-gauge stainless-steel needle 3.0-mm-long (Hamilton), according to previous studies (Maurice et al., 1996a, b; Wang et al., 2001). The needle was inserted unilaterally 1 mm to the right of the midline point equidistant from each eye, at an equal distance between the eyes and the ears and perpendicular to the plane of the skull. Peptides or sterile twice-filtered water (3 μl) were delivered gradually within 3 s. Mice exhibited normal behaviour within 1 min after injection. After 10 days, the mice were put through the passive avoidance test. To examine the anti-amnesic effect of a test drug, dimemorfan or (+)-SKF-10047 was administered i.p. 30 min before or immediately after the training trial, or 30 min before the retention test (Matsuno et al., 1994). To examine the effect of a σ receptor antagonist, haloperidol was administered i.p. 40 min before the training trial in scopolamine-induced amnesia or immediately after the training trial in β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia. All tests were performed between 1000 and 1800 h.

Place learning in the water-maze test

This experiment was according to the method of Urani et al. (1998) with some modifications. The apparatus consisted of a black plexiglass rectangular pool (30×60×36 cm high) filled with water at a height of 15 cm and a transparent plexiglass platform (5×8.5×14 cm) fixed in the southeast corner of the pool, 1 cm below the water surface. China black ink was used to render the water opaque and the water temperature was controlled at 23±1°C before experiments. Each mouse was placed in the middle of the west side of the pool, facing the wall, and the escape latency to reach the hidden platform was recorded. The mouse was allowed to stay on the platform for 20 s then removed to its home cage. Each mouse was trained in this manner for a total of five trials on day 1 and three trials on day 2. The starting point and platform location did not change during all training trials and the interval between each training trial was about 15 min. On day 4, 48 h after the last training trial, the animals were tested for retention. The platform was removed and each mouse was placed again at the starting point and observed for 60 s. The escape latency to reach and the time spent on the platform location were recorded. Scopolamine was administered i.p. 20 min before the first acquisition trial on each training day and the test drug was administered i.p. 10 min before scopolamine.

Statistical analysis

The results of the passive avoidance test were expressed as the medians with interquartile and 5th to 95th percentile ranges and the data were analysed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and followed by Mann–Whitney U-test. The results obtained from the water-maze test were expressed as means± s.e.mean and were analysed with ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test. The statistical significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

Study on scopolamine-induced amnesia in passive avoidance test

None of the drug treatments had significant effects on either the step-through latency in the training trial or the sensitivity to electric shocks throughout the passive avoidance test as compared with the control group (data not shown). As shown in Figures 1,2,3, the median values of step-through latency in the retention test for many groups of naïve mice were around 300 s. Scopolamine (1 mg kg−1, i.p.) administered 20 min before the training trial significantly reduced the median values of step-through latency to about 20 s (P<0.01).

Figure 1.

Effects of (+)-SKF-10047 on scopolamine-induced amnesia in the step-through passive avoidance test in mice. Scopolamine (1 mg kg−1, i.p.) was administered 20 min before the training trial to induce amnesia. Various doses of (+)-SKF-10047 (0.025–0.25 mg kg−1, i.p.) were administered 30 min before the training trial (a), immediately after the training trial (b), or 30 min before the retention test (c). The step-through latency was recorded in the retention test performed 24 h after the training trial. Data are expressed as medians (horizontal bar within the column), interquartile range (column), and 5th to 95th percentile range. The number of mice in each group is indicated in parentheses. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with the scopolamine-treated control group (SC) (Mann–Whitney U-test).

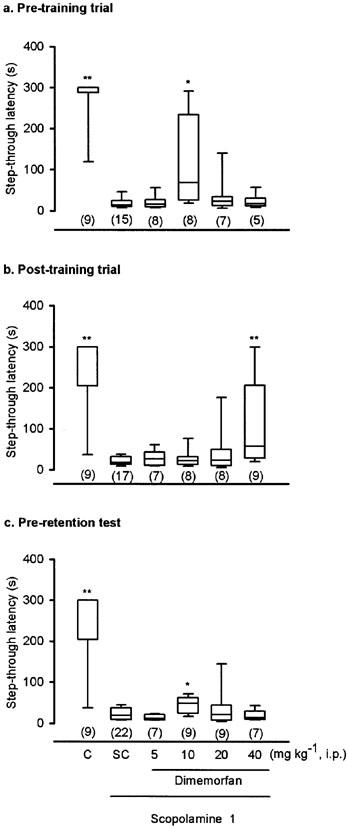

Figure 2.

Effects of dimemorfan on scopolamine-induced amnesia in the step-through passive avoidance test in mice. The experimental procedures were the same as listed in Figure 1. Various doses of dimemorfan (5–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) were administered 30 min before the training trial (a), immediately after the training trial (b), or 30 min before the retention test (c). Data are expressed as medians (horizontal bar within the column), interquartile range (column), and 5th to 95th percentile range. The number of mice in each group is indicated in parentheses. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with the scopolamine-treated control group (SC) (Mann–Whitney U-test).

Figure 3.

Effects of haloperidol on the anti-amnesic effects of (+)-SKF-10047 (a) and dimemorfan (b) in the step-through passive avoidance test in mice. Scopolamine (SCOP, 1 mg kg−1) was administered i.p. 20 min before the training trial to induce amnesia. Vehicle (10 ml kg−1), (+)-SKF-10047 (SKF, 0.1 mg kg−1) or dimemorfan (DF, 10 mg kg−1) was administered i.p. 30 min before the training trial, whereas haloperidol (HAL, 0.25 mg kg−1) was pretreated i.p. 10 min prior to SKF or DF administration. The step-through latency was recorded in the retention test performed 24 h after training trial. Data are expressed as medians (horizontal bar within the column), interquartile range (column), and 5th to 95th percentile range. The number of mice in each group is indicated in parentheses. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with SCOP-treated control group; +, #P<0.05, as compared with (SCOP+SKF) group and (SCOP+DF) group, respectively (Mann–Whitney U-test).

As shown in Figure 1, (+)-SKF-10047 (0.025–0.25 mg kg−1, i.p.) significantly attenuated scopolamine-induced amnesia when administered 30 min before the training trial (H(3)=8.66, P<0.05), immediately after the training trial (H(3)=8.40, P<0.05), and 30 min before the retention test (H(3)=9.61, P<0.05). In all three administration schedules, the dose-response curves for the anti-amnesic effect of (+)-SKF-10047 exhibited a bell-shaped pattern with the significant doses at 0.05–0.1 mg kg−1.

Because our previous study found that dimemorfan, at the doses higher than 120 μmol kg−1 (42.4 mg kg−1), produced hypolocomotion in mice, the doses examined in this test did not exceed 40 mg kg−1. As shown in Figure 2, dimemorfan (5–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) significantly attenuated scopolamine-induced amnesia when administered 30 min before the training trial (H(4)=10.20, P<0.05), immediately after the training trial (H(4)=9.90, P<0.05), or 30 min before the retention test (H(4)=9.95, P<0.05). When administered in the pre-training trial (Figure 2a) or pre-retention test (Figure 2c), the dose-response curve for the anti-amnesic effect of dimemorfan exhibited a bell-shaped pattern with the significant dose at 10 mg kg−1. However, the anti-amnesic dose of dimemorfan administered immediately after the training trial was only significant at the maximal test dose, 40 mg kg−1 (Figure 2b).

As shown in Figure 3, haloperidol pretreatment (0.25 mg kg−1, i.p., 40 min before the training trial) had no significant effect on the passive avoidance task or on scopolamine-induced amnesia but abolished the anti-amnesic effects of (+)-SKF-10047 (0.1 mg kg−1, i.p., Figure 3a) and dimemorfan (10 mg kg−1, i.p., Figure 3b) administered 30 min before the training trial.

Study on β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia in passive avoidance test

Ten days after i.c.v. administration of twice-filtered water (vehicle control) or the aggregated form of β-amyloid peptide-(25-35) (3 nmol mouse−1), mice were trained for the step-through passive avoidance task. None of the i.c.v. treatments had significant effects on either the step-through latency in the training trial or the sensitivity to electric shocks throughout the passive avoidance test as compared with the non-treated group (data not shown). As shown in Figures 4,5,6, the median values of the step-through latency in the retention test for the vehicle control group was around 111.3–295.0 s, which were comparable to those of the non-treated group (around 197.5–300.0 s). However, the β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-treated group showed a significant decrease in the median values of step-through latency in the retention test (around 18.5–25.9 s).

Figure 4.

Effects of (+)-SKF-10047 on β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia in the step-through passive avoidance test in mice. Ten days after i.c.v. administration of the vehicle, twice-filtered water (V), or the aggregated form of β-amyloid peptide-(25-35) (3 nmol mouse−1), mice were subjected to the passive avoidance test. Various doses of (+)-SKF-10047 (0.025–0.1 mg kg−1, i.p.) were administered 30 min before the training trial (a), immediately after the training trial (b), or 30 min before the retention test (c). The step-through latency was recorded in the retention test performed 24 h after the training trial. Data are expressed as medians (horizontal bar within the column), interquartile range (column), and 5th to 95th percentile range. The number of mice in each group is indicated in parentheses. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with the β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-treated control group (AC) (Mann–Whitney U-test).

Figure 5.

Effects of dimemorfan on β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia in the step-through passive avoidance test in mice. The experimental procedures were the same as listed in Figure 4. Various doses of dimemorfan (10–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) were administered 30 min before the training trial (a), immediately after the training trial (b), or 30 min before the retention test (c). Data are expressed as medians (horizontal bar within the column), interquartile range (column), and 5th to 95th percentile range. The number of mice in each group is indicated in parentheses. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with the β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-treated control group (AC) (Mann–Whitney U-test).

Figure 6.

Effects of haloperidol on the anti-amnesic effects of (+)-SKF-10047 (a) and dimemorfan (b) in β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia in the step-through passive avoidance test in mice. The experimental procedures were the same as listed in Figure 4. (+)-SKF-10047 (SKF, 0.05 mg kg−1), dimemorfan (DF, 40 mg kg−1), or haloperidol (HAL, 0.25 mg kg−1) was administered i.p. immediately after the training trial. The step-through latency was recorded in the retention test performed 24 h after training trial. Data are expressed as medians (horizontal bar within the column), interquartile range (column), and 5th to 95th percentile range. The number of mice in each group is indicated in parentheses. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-treated group; +, #P<0.05, as compared with SKF- and DF-treated groups, respectively (Mann–Whitney U-test).

As shown in Figure 4, (+)-SKF-10047 (0.025–0.1 mg kg−1, i.p.) significantly attenuated β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia when administered 30 min before the training trial (H(3)=8.05, P<0.05), immediately after the training trial (H(3)=8.37, P<0.05), or 30 min before the retention test (H(3)=11.6, P<0.01). In all three administration schedules, the dose-response curves for the anti-amnesic effect of (+)-SKF-10047 exhibited a bell-shaped pattern with the significant doses at 0.025–0.05 mg kg−1.

As shown in Figure 5, dimemorfan (10–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) significantly attenuated β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia when administered 30 min before the training trial (H(3)=8.31, P<0.05), immediately after the training trial (H(2)=7.38, P<0.05), or 30 min before the retention test (H(3)=12.4, P<0.01). The anti-amnesic effect of dimemorfan showed a dose-dependent pattern with the significant doses at 20–40 mg kg−1.

As shown in Figure 6, haloperidol (0.25 mg kg−1, i.p.) administered immediately after the training trial had no significant effect on β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia but abolished the anti-amnesic effects of (+)-SKF-10047 (0.05 mg kg−1, i.p.) and dimemorfan (40 mg kg−1, i.p.) administered immediately after the training trial.

Study on scopolamine-induced amnesia in place learning in the water-maze test

In the control group, the escape latencies for the animal to reach the platform normally decreased over the training sessions on day 1 (from around 40 s to 10 s) and day 2 (from around 15 s to 10 s), whereas the latency to reach and the time spent on the platform location were around 5 s and 10 s, respectively, in the retention test on day 4. In an initial study to choose the most appropriate dose of scopolamine to induce amnesia in this test, it was found that scopolamine (1–8 mg kg−1, i.p.) had no significant effect on acquisition profiles (i.e. latencies to reach the platform) over the training trials on day 1 and day 2 (data not shown). However, scopolamine treatment (5 mg kg−1 and 8 mg kg−1) dose-dependently increased the latency to reach the platform location (8.1±1.4 s and 17.5±2.9 s vs control 5.9±1.5 s) and decreased the time spent on the platform location (3.6±1.1 s and 2.0±0.3 s vs control 9.7±1.3 s) in the retention test on day 4. Due to its consistent and significant amnesic effect, scopolamine at the dose of 8 mg kg−1 was used in this test.

(+)-SKF-10047 (0.325–3.0 mg kg−1, i.p) or dimemorfan (5–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) treatment had no significant effect on acquisition profiles over the training trials (data not shown), but attenuated scopolamine-induced amnesia in the retention test (Figures 7 and 8). As shown in Figures 7a and 8a, (+)-SKF-10047 (1.5 and 3.0 mg kg−1) and dimemorfan (5 and 20 mg kg−1) pretreatment significantly reduced scopolamine-induced increase in the latency to reach the platform location. As shown in Figures 7b and 8b, they also reversed the scopolamine-induced decrease in the time spent on the platform location.

Figure 7.

Effect of (+)-SKF-10047 on scopolamine-induced amnesia in the water-maze test in mice. Scopolamine (8 mg kg−1) was administered i.p. 20 min before the first acquisition trial on each training day and vehicle (V, 10 ml kg−1), (+)-SKF-10047 (0.325–3.0 mg kg−1), or haloperidol (HAL, 0.25 mg kg−1) was administered i.p. 10 min before scopolamine. The retention test was performed 48 h after the last training trial, and (a) the escape latency to reach and (b) the time spent on the platform location were recorded. Data are expressed as means±s.e.mean (n=7). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with scopolamine-treated group (C); ++P<0.01, as compared with ((+)-SKF-10047 3.0+scopolamine) group (ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test).

Figure 8.

Effect of dimemorfan on scopolamine-induced amnesia in the water-maze test in mice. The experimental procedures were the same as listed in Figure 7, except that various doses of dimemorfan (5–40 mg kg−1, i.p.) were examined. The data for (a) the escape latency to reach and (b) the time spent on the platform location are expressed as means±s.e.mean (n=7). HAL means haloperidol. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, as compared with scopolamine treated group (C); ++ P<0.01, as compared with (dimemorfan 20+scopolamine) group (ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test).

Haloperidol (0.25 mg kg−1, i.p.) treatment had no significant effect on either the acquisition profiles over the training trials or scopolamine-induced amnesia in the retention test (data not shown), but it reversed the anti-amnesic effects of 3.0 mg kg−1 (+)-SKF-10047 (Figure 7) and 20 mg kg−1 dimemorfan (Figure 8).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated for the first time that dimemorfan can attenuate both scopolamine-induced amnesia in a step-through passive avoidance test as well as a water-maze test and β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia in a step-through passive-avoidance test in mice. These effects of dimemorfan, like those for the selective σ1 receptor agonist (+)-SKF-10047, were abolished by a σ receptor antagonist haloperidol, indicating the involvement of σ1 receptor activation. It is well known that haloperidol is an antagonist for dopamine D2 receptors. Because dimemorfan has no significant interaction with the D2 receptors at the concentration of 0.1 mM as determined by receptor binding assay (Wang et al., unpublished data), it is unlikely that haloperidol acts on D2 receptors to block the effects of dimemorfan.

The present study showed that both dimemorfan and (+)-SKF-10047 administered 30 min before the training trial, immediately after the training trial, and 30 min before the retention trial all improved scopolamine- and β-amyloid peptide (25-35)-induced amnesia in a step-through passive avoidance test, indicating the facilitating effect of the σ1 receptor agonist on cognitive functions in the acquisition, consolidation and retrieval stages of learning and memory. These results are consistent with an earlier study for (+)-SKF-10047 (Senda et al., 1997).

Although similar anti-amnesic effects were observed, dimemorfan was less potent than (+)-SKF-10047 to produce a comparable effect, which was consistent with its lower binding affinity for the σ1 receptors than (+)-SKF-10047 (Chou et al., 1999). The minimal effective doses (i.p.) for dimemorfan to improve scopolamine- and β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia were around 10–40 mg kg−1 in the step-through passive avoidance test, whereas it was 5 mg kg−1 in the water-maze test. These differences may be related to different administration schedules, amnesia models, and behavioural tests which involved the complexities of different learning and memory processes. Since the acute toxicity and subacute toxicity studies showed that the oral median lethal dose (LD50) and maximum nontoxic dose for dimemorfan were 514 and 50 mg kg−1, respectively, in male mice (Ida, 1997), the present i.p. anti-amnesic doses may provide the basis for examining its effective oral anti-amnesic doses in future to determine its safety margin.

The dose of scopolamine (8 mg kg−1, i.p.) used in the present water-maze test is much higher than that (2 mg kg−1, s.c.) in the study of Urani et al. (1998). Although scopolamine is known to produce sedation, it had little effect on the animals in the swimming behaviour at this test dose (data not shown). Furthermore, it also had no significant effect on acquisition profiles over the training trials on day 1 and day 2, which contrasts with the observation of Urani et al. (1998). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear because the test apparatus and protocol are almost the same except that the strain of the test animal (ICR vs Swiss mice) and the route of scopolamine administration (i.p. vs s.c.) are different. The dose of scopolamine used in the present water-maze test is also much higher than that (1 mg kg−1, i.p.) in the step-through passive avoidance test. However, dimemorfan administered in the pre-training session seems to be more potent to improve scopolamine-induced amnesia in the water maze-test than in the step-through passive avoidance test (5 mg kg−1 vs 10 mg kg−1).

The central cholinergic system plays a major role in the process of learning and memory and has been carefully articulated over the last several decades. Whitehouse et al. (1981) reported that cholinergic cell bodies are destroyed by the disease process in Alzheimer's disease patients, leading to a deficiency of the neurotransmitter ACh. On the other hand, several studies have shown that blockade of ACh effects by muscarinic receptor antagonist scopolamine caused memory deficits in both normal (Drachman & Leavitt, 1974) and elderly groups (Sunderland et al., 1987). These observations led to the experimental strategies for anti-amnesic studies that use the scopolamine-induced amnesia model, which also has become the common manipulation for anti-amnesic drug evaluations. Because β-amyloid peptide is the major constituent of senile plague that is one of the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease and represents the underlying cause of the cognitive deficits observed in Alzheimer's disease (Cummings et al., 1996), the aggregated β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia model (Maurice et al., 1996a) was used as the first step to evaluate the potential application of an anti-amnesic drug in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. In addition to its effects in the scopolamine- and β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced amnesia models, as demonstrated in the present study, σ1 receptor ligands are also found to be effective in other amnesia models in rodents such as the learning and memory deficits in senescence-accelerated mouse (Maurice et al., 1996c) and those induced by a central serotonin releaser p-chloroamphetamine (Matsuno et al., 1994), an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channel blocker dizocilpine (Maurice et al., 1994), a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor Nw-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (Maurice & Privat, 1997), an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nimodipine (Maurice et al., 1995), a protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin (Flood et al., 1988), or carbon monoxide gas (Maurice et al., 1999). In addition to the cholinergic system, σ1 receptor ligand has been reported to modulate noradrenergic (Gonzalez-Alvear & Werling, 1995), serotonergic (Bermack & Debonnel, 2001), dopaminergic (Steinfels et al., 1989; Gonzalez-Alvear & Werling, 1994), and NMDA-related glutamatergic effects (Monnet et al., 1990; Maurice & Privat, 1997). Furthermore, α1 receptor ligands are reported to increase cerebral glucose utilization (Hohmann et al., 1992), NMDA-dependent adrenocorticotropic hormone release (Iyengar et al., 1990), and the contractility of cardiac myocytes (Ela et al., 1994). The effects as summarized above may be important in the regulation of cognition and motor performance. Because therapies aimed multiple central nervous targets are thought to have more benefits on memory and cognition than treatments aimed at a single target (Buccafusco & Terry Jr, 2000), σ1 receptor ligands with the ability to modulate at multiple central neurotransmission systems appear to be able to provide this benefit. Therefore, it is worth further studying the possibility that dimemorfan is beneficial in these amnesia models because it may act on different neurotransmission systems in combination. Additionally, providing the dose required is not too toxic, its effects may justify a clinical trial in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia.

In conclusion, this study indicated that dimemorfan acts as a α1 receptor agonist to exhibit anti-amnesic effects against scopolamine- and β-amyloid peptide-(25-35)-induced memory impairments. This new finding hopefully will open a possible opportunity for the evaluation of this old antitussive drug in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Yueh-Ching Chou for providing dimemorfan, a gift from Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Company. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC 89-2320-B-010-016, NSC 89-2320-B-010-100, and NSC 90-2315-B-010-005).

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- ANOVA

one-way analysis of variance

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- σ1

sigma-1

- (+)-SKF-10047

(+)-N-allylnormetazocine

References

- BERMACK J.E., DEBONNEL G. Modulation of serotonergic neurotransmission by short- and long-term treatments with sigma ligands. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:691–699. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCCAFUSCO J.J., TERRY A.V., JR Multiple central nervous systems targets for eliciting beneficial effects on memory and cognition. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:438–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI D.W. Dextrorphan and dextromethorphan attenuate glutamate neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1987;403:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOU Y.C., LIAO J.F., CHANG W.Y., LIN M.F., CHEN C.F. Binding of dimemorfan to sigma-1 receptor and its anticonvulsant and locomotor effects in mice, compared with dextromethorphan and dextrorphan. Brain Res. 1999;821:516–519. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUMMINGS B.J., PIKE C.J., SHANKLE R., COTMAN C.W. Beta-amyloid deposition and other measures of neuropathology predict cognitive status in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 1996;17:921–933. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRACHMAN D.A., LEAVITT J. Human memory and the cholinergic system. A relationship to aging. Arch. Neurol. 1974;30:113–121. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1974.00490320001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EARLEY B., BURKE M., LEONARD B.E., GOURET C.J., JUNIEN J.L. Evidence for an anti-amnesic effect of JO 1784 in the rat: a potent and selective ligand for the sigma receptor. Brain Res. 1991;546:282–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91492-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELA C., BARG J., VOGEL Z., HASIN Y., EILAM Y. Sigma receptor ligands modulate contractility, Ca++ influx and beating rate in cultured cardiac myocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;269:1300–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLOOD J.F., SMITH G.E., ROBERTS E. Dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate enhance memory retention in mice. Brain Res. 1988;447:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ-ALVEAR G.M., WERLING L.L. Regulation of [3H]dopamine release from rat striatal slices by s receptor ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:212–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ-ALVEAR G.M., WERLING L.L. Sigma receptor regulation of norepinephrine release from rat hippocampal slices. Brain. Res. 1995;673:61–69. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01394-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNER M., MOEBIUS F.F., FLANDORFER A., KNAUS H.G., STRIESSNIG J., KEMPNER E., GLOSSMANN H. Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of the mammalian sigma1-binding site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:8072–8077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYASHI T., MAURICE T., SU T.P. Ca2+ signaling via σ1-receptors: novel regulatory mechanism affecting intracellular Ca2+ concentration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:788–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYASHI T., SU T.P. Regulating ankyrin dynamics: roles of sigma-1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:491–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOHMANN A.G., MATSUMOTO R.R., HEMSTREET M.K., PATRICK S.L., MARGULIES J.E., HAMMER R.P., WALKER J.M. Effects of 1,3-di-o-tolylguanidine (DTG), a sigma ligand, on local cerebral glucose utilization in rat brain. Brain Res. 1992;593:265–273. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IDA H. The nonnarcotic antitussive drug dimemorfan: A review. Clin. Ther. 1997;19:215–231. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IYENGAR S., MICK S., DILWORTH V., MICHEL J., RAO T.S., FARAH J.M., WOOD P.L. Sigma receptors modulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis centrally: evidence for a functional interaction with NMDA receptors, in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:299–303. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90017-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUNIEN J.L., ROMAN F.J., BRUNELLE G., PASCAUD X. JO1784, a novel sigma ligand, potentiates [3H]acetylcholine release from rat hippocampal slices. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;200:343–345. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90593-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASE Y., KITO G., MIYATA T., UNO T., TAKAHAMA K., IDA H. Antitussive activity and other related pharmacological properties of d-3-methyl-N-methylmorphinan (AT-17) Arzneimittel-Forsch. 1976;26:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEANDER J.D., RATHBUN R.C., ZIMMERMAN D.M. Anticonvulsant effects of phencyclidine-like drugs: relation to N-methyl-D-aspartic acid antagonism. Brain Res. 1988;454:368–372. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90839-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUNO K., MATSUNAGA K., MITA S. Increase of extracellular acetylcholine level in rat frontal cortex induced by (+)N-allylnormetazocine as measured by brain microdialysis. Brain Res. 1992;575:315–319. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90096-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUNO K., MATSUNAGA K., SENDA T., MITA S. Increase in extracellular acetylcholine level by sigma ligands in rat frontal cortex. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993a;265:851–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUNO K., SENDA T., KOBAYASHI T., MITA S. Involvement of α1 receptor in (+)-N-allylnormetazocine-stimulated hippocampal cholinergic functions in rats. Brain Res. 1995;690:200–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUNO K., SENDA T., KOBAYASHI T., OKAMOTO K., NAKATA K., MITA S. SA4503, a novel cognitive enhancer, with σ1 receptor agonistic properties. Behav. Brain Res. 1997;83:221–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)86074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUNO K., SENDA T., MATSUNAGA K., MITA S. Ameliorating effects of sigma receptor ligands on the impairment of passive avoidance tasks in mice: involvement in the central acetylcholinergic system. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;261:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUNO K., SENDA T., MATSUNAGA K., MITA S., KANETO H. Similar ameliorating effects of benzomorphans and 5-HT2 antagonists on drug-induced impairment of passive avoidance response in mice: comparison with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Psychopharmacology. 1993b;112:134–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02247374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., LOCKHART B.P. Neuroprotective and anti-amnesic potentials of sigma (σ) receptor ligands. Prog. in Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiat. 1997;21:69–102. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(96)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., LOCKHART B.P., PRIVAT A. Amnesia induced in mice by centrally administered beta-amyloid peptides involves cholinergic dysfunction. Brain Res. 1996a;706:181–193. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., LOCKHART B.P., SU T.P., PRIVAT A. Reversion of β25-35-amyloid peptide-induced amnesia by NMDA receptor-associated glycine site agonists. Brain Res. 1996b;731:249–253. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00710-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., PHAN V.L., NODA Y., YAMADA K., PRIVAT A., NABESHIMA T. The attenuation of learning impairments induced after exposure to CO or trimethyltin in mice by sigma (σ) receptor ligands involves both σ1 and σ2 sites. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:335–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., PRIVAT A. SA4503, a novel cognitive enhancer with σ1 receptor agonist properties, facilitates NMDA receptor-dependent learning in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;328:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)83020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., ROMAN F.J., SU T.P., PRIVAT A. Beneficial effects of sigma agonists on the age-related learning impairment in the senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM) Brain Res. 1996c;733:219–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00565-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., SU T.P., PARISH D.W., NABESHIMA T., PRIVAT A. PRE-084, a sigma selective PCP derivative, attenuates MK-801-induced impairment of learning in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;49:859–869. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., SU T.P., PARISH D.W., PRIVAT A. Prevention of nimodipine-induced impairment of learning by the selective σ ligand PRE-084. J. Neural Transm-Gen. 1995;102:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01276561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., SU T.P., PRIVAT A. Sigma1 (σ1) receptor agonists and neurosteroids attenuate B25-35-amyloid peptide-induced amnesia in mice through a common mechanism. Neuroscience. 1998;83:413–428. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE T., URANI A., PHAN V.L., ROMIEU P. The interaction between neuroactive steroids and the σ1 receptor function: behavioral consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Brain Res. Rev. 2001;37:116–132. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONNET F.P., DEBONNEL G., BERGERON R., GRONIER B., DE MONTIGNY C. The effects of sigma ligands and of neuropeptide Y on N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced neuronal activation of CA3 dorsal hippocampus neurons are differentially affected by pertussin toxin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:709–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONNET F.P., DEBONNEL G., JUNIEN J.-L., MONTIGNY C.D. N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced neuronal activation is selectively modulated by σ receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;179:441–445. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90186-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORIN-SURUN M.P., COLLIN T., DENAVIT-SAUBIE M., BAULIEU E.E., MONNET F.P. Intracellular sigma1 receptor modulates phospholipase C and protein kinase C activities in the brainstem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:8196–8199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRASAD P.D., LI H.W., FEI Y.J., GANAPATHY M.E., FUJITA T., PLUMLEY L.H., YANG-FENG T.L., LEIBACH F.H., GANAPATHY V. Exon-intron structure, analysis of promoter region, and chromosomal localization of the human type 1 σ receptor gene. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:443–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIEKKINEN P., JR 5-HT1A and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors jointly regulate passive avoidance behavior. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;262:77–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENDA T., MATSUNO K., KOBAYASHI T., MITA S. Reduction of the scopolamine-induced impairment of passive-avoidance performance by σ receptor agonist in mice. Physiol. Behav. 1997;61:257–264. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENDA T., MATSUNO K., OKAMOTO K., KOBAYASHI T., NAKATA K., MITA S. Ameliorating effect of SA4503, a novel σ1 receptor agonist, on memory impairments induced by cholinergic dysfunction in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;315:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00572-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINISCALCHI A., CRISTOFORI P., VERATTI E. Influence of N-allyl-normetazocine on acetylcholine release from brain slices: involvement of muscarinic receptors. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1987;336:425–429. doi: 10.1007/BF00164877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH G. Animal models of Alzheimer's disease: experimental cholinergic denervation. Brain Res. 1988;472:103–118. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(88)90016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINBERG G.K., KUNIS D., DELAPAZ R., POLJAK A. Neuroprotection following focal cerebral ischaemia with the NMDA antagonist dextromethorphan, has a favourable dose response profile. Neurol. Res. 1993;15:174–180. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1993.11740131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINFELS G.F., TAM S.W., COOK L. Electrophysiological effects of selective σ-receptor agonists, antagonists, and the selective phencyclidine receptor agonist MK-801 on midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1989;2:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0893-133x(89)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SU T.P. Sigma receptors. Putative links between nervous, endocrine and immune systems. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;200:633–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUNDERLAND T., TARIOT P.N., COHEN R.M., WEINGARTNER H., MUELLER E.A., 3RD, MURPHY D.L. Anticholinergic sensitivity in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type and age-matched controls. A dose-response study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1987;44:418–426. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800170032006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORTELLA F.C., MUSACCHIO J.M. Dextromethorphan and carbetapentane: centrally acting non-opioid antitussive agents with novel anticonvulsant properties. Brain Res. 1986;383:314–318. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URANI A., PRIVAT A., MAURICE T. The modulation by neurosteroids of the scopolamine-induced learning impairment in mice involves an interaction with sigma1 (σ1) receptors. Brain Res. 1998;799:64–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VENAULT P., CHAPOUTHIER G., DE CARVALHO L.P., SIMIAND J., MORRE M., DODD R.H., ROSSIER J. Benzodiazepine impairs and beta-carboline enhances performance in learning and memory tasks. Nature. 1986;321:864–866. doi: 10.1038/321864a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG H.H., CHOU C.J., LIAO J.F., CHEN C.F. Dehydroevodiamine attenuates beta-amyloid peptide-induced amnesia in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;413:221–225. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00913-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITEHOUSE P.J., PRICE D.L., CLARK A.W., COYLE J.T., DELONG M.R. Alzheimer disease: evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Ann. Neurol. 1981;10:122–126. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]