Abstract

Nootropic drugs increase glucose uptake into anaesthetised brain and into Alzheimer's diseased brain. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone, TRH, which has a chemical structure similar to nootropics increases cerebellar uptake of glucose in murine rolling ataxia. This paper shows that nootropic drugs like piracetam (2-oxo 1 pyrrolidine acetamide) and levetiracetam and neuropeptides like TRH antagonise the inhibition of glucose transport by barbiturates, diazepam, melatonin and endogenous neuropeptide galanin in human erythrocytes in vitro.

The potencies of nootropic drugs in opposing scopolamine-induced memory loss correlate with their potencies in antagonising pentobarbital inhibition of erythrocyte glucose transport in vitro (P<0.01). Less potent nootropics, D-levetiracetam and D-pyroglutamate, have higher antagonist Ki's against pentobarbital inhibition of glucose transport than more potent L-stereoisomers (P<0.001).

Piracetam and TRH have no direct effects on net glucose transport, but competitively antagonise hypnotic drug inhibition of glucose transport. Other nootropics, like aniracetam and levetiracetam, while antagonising pentobarbital action, also inhibit glucose transport. Analeptics like bemigride and methamphetamine are more potent inhibitors of glucose transport than antagonists of hypnotic action on glucose transport.

There are similarities between amino-acid sequences in human glucose transport protein isoform 1 (GLUT1) and the benzodiazepine-binding domains of GABAA (gamma amino butyric acid) receptor subunits. Mapped on a 3D template of GLUT1, these homologies suggest that the site of diazepam and piracetam interaction is a pocket outside the central hydrophilic pore region.

Nootropic pyrrolidone antagonism of hypnotic drug inhibition of glucose transport in vitro may be an analogue of TRH antagonism of galanin-induced narcosis.

Keywords: Glucose transport, nootropic action, piracetam, levetiracetam, TRH, galanin, pentobarbital, diazepam, melatonin

Introduction

Piracetam (2-oxo 1 pyrrolidine acetamide) has memory-enhancing properties, that is, it is a nootropic drug. Although many direct and indirect effects of piracetam have been reported, its mechanism of action remains unclear. Like its analogue, levetiracetam (KEPPRA, ucb L059) (Tables 1 and 2 ), it is an anticonvulsant, preventing seizures in rats induced by electroshock or drugs, for example, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) (Gower et al., 1992; Hovinga, 2001; Nash & Sangha, 2001). In addition, piracetam and its analogues reduce the confusional states induced by barbiturates, ethanol or benzodiazepines (Moyersoons & Giurgea, 1974; Salimov et al., 1995; Knapp et al., 2002). It facilitates long-term potentiation (Molnar et al., 1994), increases neurotransmitter release from presynaptic terminals and increases the amount of neurotransmitter, particularly acetylcholine, in the brain, but does not act directly on choline transport or metabolism (Nishizaki et al., 1998). Levetiracetam binds with moderate affinity (pKi=6.1) to isolated synaptic membranes (Noyer et al., 1995; Gillard et al., 2003). This binding is displaced by piracetam, pentobarbital, benzodiazepines and ‘gamma amino butyric acid (GABA)-related' substances, for example, GABA, pentylentetrazol and bemigride. However, piracetam has no direct GABAergic effects in isolated systems (Noyer et al., 1995; Fuks et al., 2003). The D-stereoisomer (ucb L060) of levetiracetam is much less effective at displacing labelled levetiracetam from the membranes (Gillard et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Direct effects of nootropics and neuropeptides on glucose exit at 25°C

|

Table 2.

Summary of effects of hypnotics anxiolytic, racetams and nootropics on glucose exit from human red cells at 25°C

|

Neuroactive dipeptides with structures similar to piracetam also have nootropic and anticonvulsive effects. Some are derivatives of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH); for example, NS-3, CG3703, cyclo-histidyl-proline and pyroglutamate have been reported to have nootropic properties (Ogasawara et al., 1995; Prasad 1995; Ostrovskaia et al., 2002) (for structures, see Tables 1 and 2). One of these, cyclo-glycyl-proline, like TRH, is endogenously formed within the brain (Gudasheva et al., 2001).

A number of drugs, hormones and disease states have been reported to alter glucose uptake and metabolism by the brain. Piracetam increases glucose uptake into the brains of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and into rat brain treated with scopolamine (Heiss et al., 1988; 1989). This may be of some therapeutic value as glucose uptake into the brains of AD patients is decreased (McGeer et al., 1986; Harik & Kalaria, 1991; Mielke et al., 1994; Santens et al., 2001). Decreased glucose uptake occurs several decades prior to the onset of dementia and diminished cortical volume in AD susceptible carriers of the apolipoprotein ɛ4 gene+/+ and is particularly associated with the posterior cingulate gyrus (Reiman et al., 2004). A possible model for this kind of neural damage modulated by glucose transport is the Nagoya ataxic mouse cerebellum in which glucose metabolism is low, and is increased by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of TRH (Kinoshita et al., 1995). TRH treatment of these ataxic rolling mice slowed the rate of neural degeneration.

Galanin secretion from the hypothalamic ventrolateral preoptic nucleus is associated with sleep activity (Crawley, 1995; Gaus et al., 2002). Intraventricular administration of galanin leads to impairment of rat learning and memory (Kinney et al., 2003). Excess galanin secretion and galanin receptor activity are found in the basal forebrains of patients with AD (Counts et al., 2001; Steiner et al., 2001; Mufson et al., 2003). Like barbiturates, galanin inhibits cognition and acetylcholine release in the brain (Bennett et al., 1997) and is reciprocally related to brain glucose concentration (Stefani & Gold, 1998). Galanin also directly inhibits glucose-induced insulin secretion in isolated pancreatic islets (Ruczynsk et al., 2002) and has effects on glucose-induced insulin secretion mediated via the central nervous system (Vrontakis, 2002).

Barbiturates (Gjedde & Rasmussen 1980; Otsuka et al., 1991; Khan et al., 1997; Lowry & Fillenz 2001), melatonin (Cassone et al., 1988), phenothiazines (Dwyer et al., 1999) and diazepam (Siemkowicz 1980; Nugent et al., 1982; Kelly et al., 1986; Eintrei et al., 1999) inhibit glucose transport both into the brain in vivo and in vitro cell systems, for example, human erythrocytes, (Naftalin & Arain, 1999; Haspel et al., 1999; Stephenson et al., 2000).

No direct effect of piracetam on glucose transport has been reported in cells, although it increases erythrocyte membrane fluidity (Muller et al., 1997). It seemed possible that some of the piracetam-dependent increases in glucose uptake into the brain might be a result of its antagonism to the effects of hypnotic or sedative drugs (Heiss et al., 1989). We decided therefore to determine if piracetam and its neuropeptide analogues had an antagonist effect on barbiturate-, benzodiazapine- or melatonin-dependent inhibition of glucose transport in human erythrocytes. We also tested whether less active D-enantiomeric forms of nootropics were correspondingly less active antagonists of barbiturate inhibition of glucose transport.

Galanin peptide was also tested to determine if it had any direct effect on erythrocyte glucose transport and whether its effects like those of barbiturates could be antagonised by piracetam.

There are sufficient similarities between actions of anaesthetics and hypnotics on human glucose transport protein isoform 1 (GLUT1) and GABAA receptor to make comparison useful. By studying similarities between primary amino-acid sequences of GLUT1 and GABAA receptor α and γ subunits close to the benzodiazepine-binding site, we have obtained a hypothetical site for this ligand interaction on GLUT1.

Methods

Solutions

The composition of the buffered saline was as follows in mM: NaCl 140; KCl 2.5; MgCl2 2.0; HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulphonic acid) 5. D-glucose and sodium pentobarbital, thiamylal, aniracetam, galanin, bemigride, methamphetamine, diazepam, flumenazil, cyclo-histidyl proline; cyclo-glycyl-proline and piracetam, aniracetam, D- and L-pyroglutamate, diazepam, melatonin, [+]- and [−]-AMMTC (N-acetyl-4-aminomethyl-6-methoxy-9-methyl-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrahydrocarbazole), thyrotropin-releasing factor (TRH) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company, Dorset. Levetiracetam and its D-stereoisomer ucbL060 were a gift from UCB-Pharma, Braine-l′Alleud, Belgium. The TRH analogue, CG 3703 (Montirelin), was obtained as a gift from Dr B. Wolf, (Grunenthal GmbH, Aachen, Germany); and Suniferam (DM 235) was a gift from Dr Fulvio Gualtieri, Department of Preclinical and Clinical Pharmacology, Viale G Pieraccini, Florence, Italy. All solutions were buffered to pH 7.4 with HCl using appropriate temperature corrections and corrections for the buffering effect of the drug. All drugs were solubilised in 50% ethanol : 50% water.

Cells

Exit of glucose was monitored as a change in light scattering due to cell volume shrinkage on net glucose loss from glucose-loaded cells into the suspension medium. Fresh human erythrocytes were obtained by venepuncture, and were washed three times in isotonic saline by repeated centrifugation and resuspension. The cells were then suspended in solutions containing D-glucose at the preloading concentration – 100 mM, final haematocrit 10%. The cells were incubated for at least 2 h, to allow the sugar to equilibrate with the cell water and then recentrifuged to obtain a thick cell suspension ca. 95% haematocrit. This cell suspension was kept at 4°C until required. Aliquots of prewarmed cell suspension (7.5 μl) were added to a 1 cm2 fluorescence cuvette containing 3 ml of saline solution that had been prewarmed to the 25°C. The cell suspensions were mixed vigorously and photometric monitoring was started within 5 s of mixing. The final glucose concentration in a nominally glucose-free solution with this regime is maximally 0.2 mM, which is at least 10-fold less than the lowest Michaelis Menten coefficient (Km) of D-glucose measured here, so contamination of the external solution with glucose has a negligible effect on D-glucose exit. All drugs were added to the external solution only. Any drug effect observed is due to immediate contact after mixing in the cuvette.

Photometric monitoring

Glucose exit: The effects of varying concentrations of D-glucose, added to external solutions, on the exit rates of glucose from cells were monitored photometrically, using a Hitachi 2000-F fluorescence spectrometer with a temperature-controlled and monitored cuvette; Eex=Eem=650 nm. The output was recorded and stored using a MacLab 2e (AD Instruments). Data were collected at a rate of 0.33–5 points s−1, depending on the time course of exit; each run consisted of ≈2000 data points. The photometric response was found to be approximately linear for osmotic perturbations ±50 mM NaCl as reported previously (Naftalin et al., 2003).

The time courses of glucose exit were fitted to monoexponential curves of the form yt=A{1−B exp(C.t)} using the Levenberg–Marquardt method of curve fitting program in Kaleidagraph 3.6 (Synergy Software). The voltage recorded at time t is yt; coefficient A is a scaling factor that fits the curves to the voltage signal, B and C are the monoexponential coefficients and t is the time in seconds at which yt is obtained. The rate coefficient, C (s−1), is used to monitor the effects of either glucose or drugs, for example, sodium pentobarbital concentration on glucose exit. Representation of glucose exit as a monoexponential gives a very good approximation both to the initial zeroth-order saturation kinetics and to the later hyperbolic relationship of flux with cell concentration ‘r'≈0.98. In all cases, the cells were exposed to test substances only during the period of glucose exit.

Statistics

All the statistical probabilities were estimated from two-tailed Student's t-values for unpaired means. The n values were estimated from the number of degrees of freedom, and all data points were obtained from the means of three to five sets of data.

The Ki values for direct inhibitors of glucose exit were obtained by nonlinear regression of the change in the exponential exit rate of glucose exit, C against the inhibitor concentration [I] using the following equation: y=VmKi/(Ki+[I]), where Ki is the inhibitor concentration giving a 50% decrease in the rate of exit obtained in the absence of inhibitor. The regression coefficient is expressed as a mean±standard error of mean (s.e.m.). Each Ki plot was obtained from the means of glucose exit rates of at least three to four inhibitor concentrations, that is, typically 16 to 20 glucose exit rates were determined per estimate of each Ki. Each Ki estimate was repeated three to four times.

Monitoring the affinity of glucose at the external site (infinite cis Km) and the maximal rate of glucose exit (zero-trans Vm)

With glucose concentration nominally at zero in the external solution, exit is defined as the zero-trans net exit condition and monitors the maximal rate of glucose net exit, Vm. To measure the affinity of glucose for the external side of the transporter, the rates of glucose exit were obtained with varying concentrations of glucose in the external solution. The glucose concentration in the external solution required a reduction in the rate of net glucose exit by 50%=the infinite cis Km. This mode of characterising exit, where the initial inside glucose concentration is fixed (infinite cis), but the rate of exit is varied by addition of glucose to the external solution, was introduced by Sen & Widdas (1962). The Km is obtained by least-squares fit of the equation v=KmVm/(Km+Gex), where Vm is the maximal rate of glucose exit in the uninhibited state and Km is the concentration of glucose in the external solution Gex required to reduce the exit rate to 50% of the uninhibited rate. Hypnotics like sodium pentobarbital, etc. were also tested to determine whether they alter the affinity of glucose for the external site, that is, Ki(ic glucose/pentobarbital). The Ki (ic glucose/pentobarbital) is obtained by observing the increase in the apparent Km of glucose binding to the external site, as a function of pentobarbital concentration (Naftalin & Arain 1999). This was obtained by plotting the apparent Km(ic glucose) versus [pentobarbital]. The Ki(ic glucose/pentobarbital) is obtained from the intercept/slope±s.e.m. regression line.

The Ki values for indirect inhibition, for example, the effect of aniracetam on pentobarbital or diazepam, were obtained by linear regression of the apparent Ki values (Kapp) of pentobarbital against the inhibitor concentration [I].

As Kapp=Ki1(1+ [I]/Ki2), thus [I] is the concentration of modulator, for example, piracetam required to increase Ki1 of the primary inhibitor (e.g. pentobarbital) by two-fold. This is obtained from (intercept/slope)±s.e.m. of the linear regression line of Kapp versus [I].

Sequence homologies between the benzodiazepine-binding domain of the GABAA receptor and GLUT1

Homologies were sought between sequences close to the ligand-binding domain of the human and rat GABAA receptor, human GAA1, primary accession number P14867 and gamma-aminobutyric-acid receptor gamma-2 subunit precursor (GABAA γ receptor); GAC2_Human primary accession number P18507; also rat.alpha1 gamma-aminobutyric-acid receptor alpha-1 and rat.gamma2; Gamma-aminobutyric-acid receptor AC P15433, GABRG2. Rattus norvegicus (Rat) AC P18508 in GLUT1, GLUT-1 (SLC2A1) accession number P11166 using the Swissprot database human primary is as follows: FASTA (Pearson & Lipman, 1988) was used to identify and evaluate the partial matches between GLUT1 and sequences in the human GABAA receptor, α, β and γ subunits adjacent to the ligand-binding cleft. The matches were applied to the 2-D template structure of GLUT-1 (Mueckler et al., 1985) and to its putative 3-D structure (Zuniga et al., 2001), and to the template of the major facilitator superfamily (MSF) (Hirai et al., 2003). The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 1JA5) are in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, U.S.A. (http://www.rcsb.org/) and can be viewed with Swiss-Pdb viewer, http://www.expasy.ch/spdbv.

Results

Reversal by piracetam of both reduction in affinity and Vm of the glucose transporter by pentobarbital

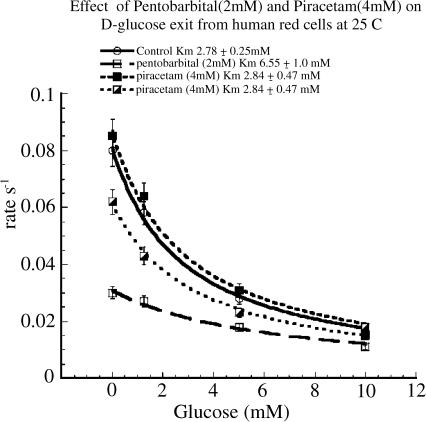

Pentobarbital acts as a mixed inhibitor of glucose transport. It decreases the Vm of zero-trans net glucose exit and entry and decreases the affinity of glucose binding (increases the Km of infinite-cis glucose net exit) to the exofacial surface of GLUT1 (Naftalin & Arain 1999; Stephenson, 2000). Piracetam alone had no significant effect on either the affinity of D-glucose for the external site of the transporter or the Vm rate of D-glucose exit. However, comparison of the effects of pentobarbital alone with pentobarbital and piracetam together showed that piracetam reversed the effects of pentobarbital on both the maximal rate of exit, Vm and the affinity of D-glucose for the external site of the transporter. The affinity of glucose was reduced from 6.55±1.0 mM with pentobarbital (2 mM) present to 3.25±0.45 mM (P<0.025) with both pentobarbital (2 mM) and 4 mM piracetam together. In addition, the maximal rate of glucose exit into an external solution containing zero-glucose in the external solution was increased from 0.031±0.001 s−1 with pentobarbital (2 mM) to 0.061±0.002 s−1 (P<0.001), Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effect of pentobarbital (2 mM) and piracetam (4 mM) on D-glucose exit rate from human red cells at 25°C into solutions containing varied (glucose) concentrations. Pentobarbital reduced the maximal rate of zero-trans net glucose exit to 0.031±0.001 s−1 from a control rate of 0.061±0.002 s−1 (P<0.001). The infinite cis Km was 6.55±1.0 mM with pentobarbital (2 mM) and 2.78±0.25 mM in control. Piracetam (4 mM) in the copresence of pentobarbital (2 mM) significantly increased the maximal rate of zero-trans exit (P<0.001) and reduced the infinite cis Km of glucose to 3.25±0.45 mM (P<0.025). On its own, in comparison with control rates, piracetam (4 mM) had no effect. Error bars are the s.e.m.'s of four to five separate determinations of rates. This experiment was repeated five times with similar results. The lines drawn are the least-squares best-fit nonlinear regression lines to the equation for competitive inhibition (see Methods).

Increased concentrations of pentobarbital required higher concentrations of piracetam to antagonise their effects. The Ki for the inhibition of D-glucose exit by pentobarbital was 1.29±0.17 mM. With increasing concentrations of piracetam, the apparent Ki of pentobarbital was progressively increased (Figures 2 and 3). Piracetam also reversed the pentobarbital-dependent increase in infinite-cis Km of glucose at the external site (Figure 1). A Dixon plot of these data shows that the Ki of piracetam antagonism of pentobarbital on D-glucose exit is 0.83±0.13 mM (Figure 3). As the relationship between the apparent Ki of pentobarbital inhibition of D-glucose exit and piracetam concentration is linear, it is evident that piracetam acts as a competitive antagonist of pentobarbitone-dependent inhibition of glucose exit from human erythrocytes.

Figure 2.

Effect of varying concentrations of piracetam on the pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of zero-trans net glucose exit from human erythrocytes. Increasing concentrations of piracetam caused a linear increase in the apparent Ki of pentobarbital inhibition of glucose exit rates. Error bars are s.e.m.'s of four to five separate estimates of the rates of glucose exit. The lines drawn between the points are the least-squares best-fit nonlinear regression lines to the equation for competitive inhibition (see Methods).

Figure 3.

Dixon plots of piracetam, levetiracetam and its D (+) stereoisomer ucb L060 on the apparent Ki of pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of zero-trans glucose exit. This is a replot of data shown in Figure 2. Increasing concentrations of piracetam, levetiracetam (ucb L059) and ucb L060 significantly compete with pentobarbital action on glucose transport. The lines are the least-squares linear regression lines. The secondary Ki's are estimated as outlined in Methods.

As piracetam also competitively antagonises pentobarbital action on the infinite cis exit Km of glucose exit, it is likely that piracetam and pentobarbital competitively bind to contiguous sites (see Discussion).

Effects of levetiracetam, its D-stereoisomer ucb L060 and piracetam on pentobarbital inhibition of D-glucose exit

There was a concentration-dependent reduction in pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose exit following the addition of levetiracetam. In the concentration range 0–500 μM, levetiracetam without pentobarbital present had a negligible effect on glucose exit. However, with levetiracetam >1 mM, some inhibition of glucose exit was observed. This differs from piracetam, which had a negligible effect on glucose exit (see Table 1 and below). A Dixon plot of the apparent Ki of pentobarbital with increasing concentrations of levetiracetam showed that, like piracetam, levetiracetam competitively antagonised pentobarbital inhibition of glucose transport albeit with higher affinity than either its D-stereoisomer, ucb L060, or piracetam (Figure 3).

Effects of piracetam and levetiracetam on thiamylal, diazepam and melatonin inhibition of glucose exit from human erythrocytes at 25°C

Effects on thiamylal

Thiamylal, like pentobarbital, inhibits glucose transport in human erythrocytes (Haspel et al., 1999). Thiamylal inhibition of glucose transport was also antagonised by levetiracetam (Table 2). Comparison of the antagonist Ki's of levetiracetam against pentobarbital and thiamylal showed that the Ki(levetiracetam/pentobarbital)=0.42±0.05 mM was significantly higher than Ki(levetiracetam/pentobarbital)=0.12±0.01 mM (P<0.001) (Table 1). This finding is consistent with pentobarbital, thiamylal and levetiracetam binding at the same site.

Effects on diazepam

Diazepam has been shown to inhibit glucose transport in erythrocytes, and it also reduces glucose metabolism in the brain (Klepper et al., 2003). Diazepam, like pentobarbital, was observed to act as a mixed inhibitor of glucose transport (Tables 1 and 2). The Ki(diazepam) at 25°C for the inhibition of glucose exit is 50.35±6.29 μM. It also reduced the affinity of glucose for the external site, Ki(infinite cis)=57±4.9 μM. Levetiracetam reversed the inhibition by diazepam of glucose exit (Tables 1 AND 2). The benzodiazepine antagonist, flumazenil, antagonised the effects of both benzodiazepine and melatonin on GABAA receptor (Wang et al., 2003). However, it had no antagonist effect on diazepam-dependent inhibition of glucose exit. This absence of effect of flumazenil and the relatively high Ki of diazepam action suggest that the diazepam-binding site on GLUT1 differs substantially from its high-affinity site on GABAA receptor. TRH had a surprisingly high antagonist Ki against diazepam (see below).

Effect of melatonin

Melatonin like barbiturates and diazepam inhibited glucose exit (Table 1). The melatonin receptor agonist, AMMTC, exists in chiral D (+) or L (−) forms (Sugden et al., 1995). Binding assays to pineal membranes show that the L(−) form of AMMTC is at least 100-fold more potent than the D form. L (−) AMMTC was ≈4-fold more effective at inhibiting glucose exit from erythrocytes than D(+) AMMTC. Melatonin inhibition of glucose exit was antagonised by piracetam (Ki=0.92±0.23 mM) and also by TRH and CG3703 (see Table 2). Piracetam and TRH antagonised melatonin-dependent inhibition of glucose exit with Ki's similar to those antagonising pentobarbital inhibition (Tables 1 and 2). These findings indicate that melatonin, like diazepam, binds to GLUT1 at a low-affinity site, which has specificity differences from the high-affinity binding sites in pineal membranes.

Effect of the galanin on glucose transport

The anxiolytic neuropeptide galanin (Bing et al., 1993) inhibited glucose exit from erythrocytes in a manner similar to pentobarbital, diazepam or melatonin, in that it reduced the Vm of zero-trans net entry and increased the Km of glucose binding at the exofacial surface of GLUT1 (Tables 1 and 2). These effects of galanin-like pentobarbital were competitively antagonised by levetiracetam. Levetiracetam was five times more potent at antagonising galanin inhibition of glucose exit than against pentobarbital, thiamylal or diazepam (Tables 1 and 2).

Effects of TRH and its analogues, CG3702, CG 3509, DM 235, cyclic glycyl proline, on pentobarbital inhibition of glucose exit

The tripeptide TRH, pyroglutamyl-histidyl-proline, and its analogues have been noted to increase glucose metabolism in the brain following ischaemia, (Katsumata et al., 2001). TRH has structural similarities to substituted pyrrolidines-like piracetam (see Tables 1 and 2). This structural similarity may relate to the similar effects of these compounds on barbiturate-dependent inhibition of glucose transport. TRH exerted a strong antagonism to the inhibition of glucose transport by both pentobarbital and melatonin (Tables 1 and 2). Surprisingly, it had a much lesser effect on diazepam-dependent inhibition of glucose exit than on either pentobarbital- or melatonin-dependent inhibitions. Like piracetam, TRH had no observable inhibitory effect on glucose exit in the concentration range tested.

The cyclic peptide, cyclic glycyl-proline, like TRH has been reported to have nootropic effects similar to those of piracetam (Ogasawara et al., 1995; Prasad, 1995; Gudasheva et al., 2001; Ostrovskaia et al., 2002). Cyclic glycyl-proline had strong antagonist effects on pentobarbital inhibition of glucose exit (Ki=90±17 μM). It also had a weak direct inhibitory effect on glucose exit Ki (Tables 1 and 2).

Three other peptides with properties similar to TRH, that is, CG 3509, CG3703 and DM 235 were tested. CG 3703 and DM 235 were very potent antagonists of pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose transport. However, low concentrations of CG3703 and DM235 directly inhibited glucose exit. CG3509 was ineffective as an antagonist of pentobarbital on glucose transport (see Discussion and Table 2). Another peptide derivative of TRH, cyclo (His-Pro), had no antagonist effect against pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose transport.

Effects on analeptics, bemigride and methamphetamine on pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose exit from human erythrocytes

The analeptic drugs bemigride and methamphetamine displace labelled levetiracetam binding from brain membranes (Noyer et al., 1995). Both drugs acted as partial antagonists of glucose transport with maximal inhibitions of exit flux confined to approximately 30 and 15%, respectively, of maximal exit (Figure 4a). Although both drugs had antagonist effects against pentobarbital, this antagonism had a hyperbolic, rather than a linear relationship, as was observed with piracetam or levetiracetam concentrations (Figure 3). At low concentrations of bemigride (<25 μM), the apparent Ki of bemigride against pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose exit was 4.5±0.3 μM. With concentrations of methamphetamine <400 μM, its antagonist Ki against pentobarbital was 130±30 μM (Figure 4b). Methamphetamine and bemigride, unlike other analeptic nootropic drugs, for example, piracetam and levetiracetam, have higher antagonist Ki's against pentobarbital inhibition of glucose exit than their Ki's for direct inhibition of glucose exit (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

A Effects of bemigride and methamphetamine on zero-trans glucose exit rates from erythrocytes. Bemigride and methamphetamine caused partial inhibitions in glucose exit. Bemigride inhibits glucose exit by 30% and methamphetamine causes a maximal inhibition of glucose exit of 15%. Bemigride inhibits glucose with a relatively high potency Ki=10.5±2.5 μM but low efficacy. Methamphetamine inhibits glucose with lower potency, Ki 118±44 μM and very low efficacy. (b) The antagonist effects of bemigride and methamphetamine on the apparent Ki of pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose exit from erythrocytes. The Dixon plots showing hyperbolic relationships of apparent Ki with increasing inhibitor concentrations. At low concentrations of bemigride and methamphetamine, there is a rapid increase in apparent Ki of pentobarbital-dependent inhibition. This increase in Ki plateaus at raised concentrations of bemigride or methamphetamine. The lines fitted to the data are hyperbolas of the form ax/(b+x)+z, where x is the concentration of inhibitor (μM), a is the maximal apparent Ki of pentobarbital inhibition of glucose exit, b is the concentration of x giving half-maximal increase in apparent Ki and z is the Ki of pentobarbital with zero antagonist present. The Ki of bemigride or methamphetamine at low concentrations=zb/a. The best-fit lines and error estimates of a, b and z were obtained using Kaleidagraph 3.6, as in Methods. The antagonist Ki's of bemigride=4.5±0.3 μM and for methamphetamine=130 30 μM.

Discussion

Until now, as stated by Pranzatelli (1997), ‘ piracetam is a drug in search of a mechanism of action'. This report showing that nootropic drugs, like piracetam and other ‘racetams', act as competitive antagonists of barbiturate, diazepam and melatonin inhibition of glucose transport is the first showing any direct effect of piracetam on a specific transporter or receptor. It is known that piracetam inhibits barbiturate intoxication (Moyersoons & Giurgea 1974; Gouliaev & Senning, 1994). There are also a number of reports showing that levetiracetam and piracetam oppose GABAA antagonist action, for example, bicuculline and gabazine (Poulain & Margineanu 2002), and reverse the inhibitory effect of negative allosteric modulators, for example, zinc and β-carbolines on both GABAA receptor- and glycine receptor-mediated responses (Rigo et al., 2002). It has also been reported that piracetam can displace [3H]flunitrazepam from rat hippocampal membranes in the presence of GABA (Rozhanets et al., 1986). These findings suggest that piracetam and its analogues bind to GABAA receptor after it is activated by barbiturates or benzodiazepines, as found here with piracetam interaction on glucose transport. Despite these findings, there is no evidence of direct binding of piracetam or levetiracetam to GABAA receptor (Noyer et al., 1995; Fuks et al., 2003).

Mechanism of action of piracetam on glucose transport

Piracetam has no effect on D-glucose transport in human erythrocytes on its own. Only in the presence of pentobarbital is its action evident. A simple kinetic scheme describes this reaction:

|

where E is the empty pentobarbital-binding site, EB is the site with pentobarbital bound, EP is the site with piracetam bound, KB and KP are the dissociation constants of pentobarbital and piracetam for the site, respectively, and T is the total number of sites available.

It is assumed that the transporter state EB inhibits glucose transport, whereas states EP and E are permissive for glucose transport. Thus, the equation for EB expressed in terms of solution concentrations of pentobarbital and piracetam is equivalent to an expression for competitive inhibition of glucose by pentobarbital, which is competitively antagonised by piracetam.

Neuropeptide interactions with glucose transport

This is the first report showing that nootropics antagonise galanin action. Galanin reduces cognitive function and increases drowsiness (Bing et al., 1993; Gaus et al., 2002). Excess galanin secretion is associated with AD (Counts et al., 2001; Steiner et al., 2001). Consequently, antagonism between nootropics and hypnotics with galanin-like effects could be of physiological as well as pharmacological importance.

TRH antagonises the hypnotic effect of pentobarbital (Sharp et al., 1984) and of ethanol (Morzorati & Kubek, 1993). I.p. injection of TRH improved glucose utilisation in the cerebellum and the ventral tegmental area of Nagoya ataxic rolling mice and slowed the progression of ataxia in the mutant (Kinoshita et al., 1995). TRH-like peptides, for example, pGlut-Glu-Pro-NH2, are as effective as TRH in arousing mice sedated with pentobarbital, yet have a negligible affinity for the TRH receptors, TRH receptor1 and TRH receptor2. This indicates that arousal from sleep is unlikely to be mediated via the TRH-specific receptors (Hinkle et al., 2002) and that 2His in TRH is not necessary to elicit the arousal response. Only the pyroglutamyl and glycine residues within TRH, similar to cyclo-glycylproline, piracetam or pyroglutamate, are required. Our finding that TRH acts as an antagonist of pentobarbital-, melatonin- and diazepam-dependent inhibitions of glucose transport in erythrocytes (Tables 1 and 2) indicates that it may similarly act on glucose uptake into neurones inhibited by neuropeptides or hypnotic drugs.

These data suggest that endogenous neuropeptides, for example, TRH and cyclo-glycylproline play a similar role to nootropics in displacing or competing for sites occupied by endogenous hypnotics, for example, galanin, thereby maintaining a balance between consciousness and sleep and modulating cognition (Horita, 1998).

More general implications of these findings

The most important question raised by the present work is whether ‘racetam' actions in antagonising drug-dependent inhibition of glucose transport are relevant to their nootropic effects. Evidence that the nootropic effects are related to antagonism of hypnotic inhibition of glucose transport by drugs, like pentobarbital, or neuropeptides like galanin is demonstrated by the significant correlation (P<0.01) between the nootropic dose in vivo required to antagonise scopolamine-induced memory loss and Ki's of nootropic drugs opposing the action of pentobarbital on glucose transport (Figure 5). This correlation can be extended (Tables 1 and 2); D-levetiracetam, D-pyroglutamate and the less potent D-form of CG2703 nootropics also have no detectible direct inhibitory effects on glucose transport, whereas their more potent L-stereo-isomers are inhibitory.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the in vivo potency of nootropic effects of drugs and their antagonist Ki against pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose transport in red cells. The linear regression line is weighted by the s.e.m.'s of Ki (Table 1), and shows the relationship between in vivo nootropic potency and Ki of in vitro antagonism of nootropics against pentobarbital inhibition of glucose transport in erythrocytes (d.f.=(N-2)=7; correlation coefficient r=0.804; P<0.01). The circled numbers refer to the following drugs.  DM235 (Ghelardini et al., 2002);

DM235 (Ghelardini et al., 2002);  CG370 (Ogasawara et al., 1995);

CG370 (Ogasawara et al., 1995);  Cyclo (pro-gly) (Seredenin et al., 2002);

Cyclo (pro-gly) (Seredenin et al., 2002);  TRH (Brooks et al., 1987);

TRH (Brooks et al., 1987);  (Abou-Khalil et al., 2003; Brooks et al., 1987; De Reuck & Van Vleymen, 1999; Devinsky & Elger, 2003);

(Abou-Khalil et al., 2003; Brooks et al., 1987; De Reuck & Van Vleymen, 1999; Devinsky & Elger, 2003);  Piracetam (Koskiniemi et al., 1998; De Reuck & Van Vleymen, 1999; Genton et al., 1999);

Piracetam (Koskiniemi et al., 1998; De Reuck & Van Vleymen, 1999; Genton et al., 1999);  Aniracetam (Spignoli & Pepeu, 1987);

Aniracetam (Spignoli & Pepeu, 1987);  L-Pyroglutamate (Spignoli et al., 1987);

L-Pyroglutamate (Spignoli et al., 1987);  L060 (Noyer et al., 1995). The in vivo potencies of the drugs were obtained from literature reports of the i.p. dose required to observe a significant nootropic response against scopolamine-induced memory loss. The curvilinearity of the regression line is introduced by using the logarithmic axes required to show the full range of the regression. The regression line is weighted to the errors of the antagonist Ki's of the drugs using the software package in Kaleidagraph 3.6.

L060 (Noyer et al., 1995). The in vivo potencies of the drugs were obtained from literature reports of the i.p. dose required to observe a significant nootropic response against scopolamine-induced memory loss. The curvilinearity of the regression line is introduced by using the logarithmic axes required to show the full range of the regression. The regression line is weighted to the errors of the antagonist Ki's of the drugs using the software package in Kaleidagraph 3.6.

The significant linear correlation between the potency of nootropic drug effects in vivo and the antagonist Ki of nootropic drugs against hypnotic drug-induced inhibition of glucose transport in human erythrocytes in vitro indicates that nootropic drug action on glucose transport may have both neurophysiological as well as neuropharmacological relevance. Although nootropic drug-dependent increases in glucose uptake could improve cognitive function in hypoglycaemic brain regions, it is entirely possible that nootropics affect other neural processes in ways analogous to their effect on GLUT1, perhaps on isoforms of the GABAA receptor, which have not been fully investigated as yet.

On the other hand, the effects of hypnotics and nootropics observed here on glucose transport in erythrocytes may simply mirror their effects on receptors elsewhere. Their inhibitory and antagonist effects on glucose transport may have no direct physiological importance. Piracetam-stimulated glucose uptake into the brain (Heiss et al., 1988; Mielke et al., 1994) may be a consequence of underlying changes in metabolic turnover by glial cells and neurons, rather than a direct effect on transport.

Only simultaneous testing of nootropic drug effects on brain glucose uptake and neural activity stimulated by local application of excitatory amino acids can provide an answer to the question of whether increased glucose transport has a primary significance to brain function, cognition and memory or is secondary to enhanced neural activity (Browne et al., 1998). Nevertheless, the new antagonistic relationships described here between the opposing actions of hypnotic drugs and nootropic on GLUT1 may be a useful analogue for further elucidation of nootropic drug action.

The evidence favouring a linkage between glucose uptake and loss or improvement of cognition in AD is the nootropic-dependent improvement in cognition in AD, particularly in subjects with APOE-3/4 (Cacabelos et al., 2000). There is also a decrease in GLUT1 expression in brain capillaries in AD (Harik & Kalaria, 1991) and a reported functional improvement in AD patients treated with Cerebrolysin, a neurotrophic drug (Ruether et al., 2002) that increases GLUT1 expression in the blood–brain barrier (Boado et al., 1999). Diminished uptake in brain glucose uptake in APOE-4 +/+ subjects decades prior to the onset of clinical symptoms (Reiman et al., 2004) suggests that deficiency in glucose transport and cognition are only indirectly linked. This implies that reversal of this chronic deficiency could have a prophylactic role in slowing brain degeneration in AD.

Comparison of direct inhibition of glucose transport with indirect action on glucose transport by antagonism of hypnotic induced inhibition of glucose transport

Nootropic drugs have been demonstrated here to have two actions on glucose transport. Some inhibit glucose transport directly. The other effect is to antagonise the inhibition of glucose transport by hypnotic drugs. Three classes of nootropic action are found. Some nootropics only have an antagonistic effect on hypnotics without any direct inhibition of glucose transport in the range of concentrations used, for example, TRH, piracetam and cyclo-prolylglycine (Figure 6 and Tables 1 and 2). These agents have a high Ki ratio ≈40–100 for antagonism of pentobarbital in comparison with their Ki's for inhibition of glucose exit. A second class, including levetiracetam, L-pyroglutamate, DM 235, aniracetam and the TRH agonist, CG 3703, has Ki ratios in the range 4–20, that is, they antagonise pentobarbital inhibition of glucose, but at higher concentrations they inhibit glucose transport. A third group consists of analeptic drugs, bemigride and methamphetamine. Both act as partial antagonists of glucose transport having a high affinity for GLUT1, but only induce an incomplete inhibition of sugar exit ≈30%. In addition, neither of these drugs has a strong antagonist effect against pentobarbital-induced inhibition of glucose flux (Figure 6). They have Ki ratios of direct inhibition: antagonism against pentobarbital <1.

Figure 6.

Histograms showing the ratios of Ki's for indirect antagonism of pentobarbital-dependent inhibition of glucose exit and the Ki of inhibition of glucose exit by the drug. Also shown are the Ki's of drug antagonism against pentobarbital-dependent inhibition. The inhibitions of glucose exit by TRH, piracetam, L-pyroglutamate and ucb L060 are very small, so the Ki's of inhibition of glucose are likely to be underestimates. Thus, the Ki ratios of direct inhibition of glucose: indirect antagonism of pentobarbital by these drugs may be underestimates.

If a major function of nootropic drug action is to antagonise hypnotic drug effects on glucose transport, then it is counterproductive if it also inhibits glucose transport. It can be seen from Figure 6 that there is only a weak correlation between the Ki for direct inhibition of glucose transport and the Ki for antagonism of pentobarbital.

Tentatively, it can be suggested that group 1 drugs are useful nootropics as they antagonise inhibition of glucose uptake by endogenous agents, for example, galanin and drugs like barbiturate, without themselves inhibiting glucose uptake. Group 2 that includes drugs like levetiracetam make better antiepileptics than nootropics, as they have a modest inhibitory effect on glucose uptake, similar to pentobarbital, which is both a hypnotic and an antiepileptic drug. The analeptic effects and seizure-promoting effects of bemigride and amphetamines are unlikely to be explicable in terms of their very modest effects on glucose transport. Their relatively high affinities as antagonists of pentobarbital may mirror similar effects on GABA or glycine receptors in preventing the action of endogenous sedatives like galanin.

Search for similarities between GLUT1 and the benzodiazepine-binding site of GABAA receptor

Barbiturates have a wide variety of affinities on many receptors and transporters (Marszalec & Narahashi, 1993; Daniell, 1994; Germann et al., 1994; Koltchine et al., 1996; Krampfl et al., 2000). The site with highest sensitivity to barbiturates and benzodiazepines is the pentameric, GABAA receptor. Its isoforms have affinities for pentobarbital in the range 58–528 μM (Thompson et al., 1996, Adkins et al., 2001; Wallner et al., 2003). GABAA receptor also binds benzodiazepines and steroid anaesthetics (for review, see Smith & Olsen 1995). GABAA receptor consists of 2α, 2β and a single γ subunit. GABA binds to extracellular loops between α and β subunits, whereas benzodiazepines bind between α and γ subunits (Cromer et al., 2002; Sigel, 2002; Ernst et al., 2003). Anaesthetics act on GABAA receptor by increasing the open probability of the chloride conductance channel following GABA binding, thereby increasing the efficacy of GABA (Wallner et al., 2003).

Our previous work has shown that there are similarities between the ligand-binding domains of the human oestrogen receptor and the endofacial surface of GLUT1 (Afzal et al., 2002), and between human androgen receptor ligand-binding domain and the exofacial surface of GLUT1 (Naftalin et al., 2003). Since pentobarbital and benzodiazepine binding to GABAA receptor sites have been identified as being at the interface between γ and α subunits (Smith & Olsen 1995; Thompson et al., 1996; Cromer et al., 2002; Sigel 2002; Ernst et al., 2003), we looked for homologous sequences in GLUT1 to those in GABA implicated in benzodiazepine binding (see Methods). Although the overall percentage similarity between GABA subunits and GLUT1 is only 28.7±1.5 (s.d.) and the percentage homology is 19.7±1.8 (s.d.), there are localised regions within GLUT1 with a much higher percentage similarity to the benzodiazepine-binding region of GABAA, which points to a possible binding site for benzodiazepine in the N-terminal half of GLUT1 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Map of regions of similarity between GABAA receptor and GLUT1 on the basic skeleton of GLUT1 showing the relative positions of the transmembrane helices and the exofacial and endofacial linkers. Regions of similarity between GABAA receptor and GLUT1. The labels α, β and γ refer to the GABA receptor subunits. A, B and C are positions of benzodiazepine-binding loops in subunit α and E and D in subunit γ forming a single benzodiazepine-binding pocket within GABAA receptor (Sigel and Buhr 1997; Ernst et al., 2003). The 3-D structure of GLUT1 is shown using the known topology of the 12 transmembrane helices of the major facilitator superfamily (Hirai et al., 2003). The positions of the similarities A–E with equivalent regions on GABAA receptor are shown. The exofacial linkers between the transmembrane helices are shown either as a dotted line where similarities with GABAA receptor are present or as a continuous line. The endofacial linkers are not shown. Glucose is thought to bind within the central hydrophilic pore (Mueckler & Makepeace, 2004). The rhomboid shape represents the position where benzodiazepine may bind. It is surrounded by six regions of similarity within the benzodiazepine-binding domain of GABAA receptor (see Table 3). This region could form a noncatalytic site of inhibition of glucose transport by preventing glucose-induced conformational changes.

The putative region where benzodiazepine binds in GLUT1 is close to the exofacial surface, surrounded on four sides by regions with a high similarity to the benzodiazepine-binding loops in rat GABAA α and γ subunits localised around the external linker sequences between transmembrane helices 1 and 2 and between 3 and 4 (see Table 3 , Figure 7). No previous inhibitor has been observed to bind within the N-terminal half of GLUT1 (Naftalin, 2003). This hypothetical site for barbiturate and possibly nootropic binding on GLUT1 is suitably placed to act as a noncatalytic inhibitor of glucose transport, as it is does not impinge on the hydrophilic pore, through which it is presumed that glucose traverses GLUT1. Binding at this site could prevent the conformational changes required of net sugar transport, but would not compete directly with glucose binding to the transporter. This same model of GLUT1, based on the 3-D structure of the major facilitator superfamily (Hirai et al., 2003), has also been used recently to confirm the site for glucose binding within the central hydrophilic pore (Mueckler & Makepeace, 2004). Nootropics binding at this site can be presumed to compete with hypnotic binding, but permit the conformational changes induced by glucose, which facilitate transport. Similarly, low-affinity binding of racetams may occur at neurotransmitter receptors and could explain how drugs like levetiracetam compete with a range of hypnotic drugs, yet cannot be demonstrated to bind directly to receptors (Noyer et al., 1995; Fuks et al., 2003; Gillard et al., 2003).

Table 3.

Sequence similarities between GLUT1 and rat GABAA receptor subunits α1 and γ2 position on GABA and GLUT are shown in Figure 7

|

The sequences are obtained in comparison with the benzodiazpine-binding folds in rat GABAA subunits (Sigel & Buher, 1997; Ernst et al., 2003) letters A–E. The Smith–Waterman scores (1981) are indices of similarity between sequences based on identity (homology) or similarity, where similar amino-acid types are substituted leading to minimal conformation changes. A penalty is deducted for gaps in the alignments as well as for substitutions.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AMMTC

N-acetyl-4-aminomethyl-6-methoxy-9-methyl-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrahydrocarbazole

- GABA

gamma amino butyric acid

- GLUT1

human glucose transport protein isoform 1

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulphonic acid)

- Ki

inhibitor constant

- Km

Michaelis Menten coefficient

- MSF

major facilitator superfamily

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- s.e.m.

standard error of mean

- TRH

thyrotropin-releasing hormone

- Vm

maximal velocity of exit

References

- ABOU-KHALIL B., HEMDAL P., PRIVITERA M.D. An open-label study of levetiracetam at individualised doses between 1000 and 3000 mg day(−1) in adult patients with refractory epilepsy. Seizure. 2003;12:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(02)00292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADKINS C.E., PILLAI G.V., KERBY J., BONNERT T.P., HALDON C., MCKERNAN R.M., GONZALEZ J.E., OADES K., WHITING P.J., SIMPSON P.B. Alpha4beta3delta GABA(A) receptors characterized by fluorescence resonance energy transfer-derived measurements of membrane potential. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:38934–38939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AFZAL I., CUNNINGHAM P., NAFTALIN R.J. Interactions of ATP, oestradiol, genistein and the anti-oestrogens, faslodex (ICI 182780) and tamoxifen, with the human erythrocyte glucose transporter, GLUT1. Biochem. J. 2002;365:707–719. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENNETT G.W., BALLARD T.M., WATSON C.D., FONE K.C. Effect of neuropeptides on cognitive function. Exp. Gerontol. 1997;32:451–469. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(96)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BING O., MOLLER C., ENGEL J.A., SODERPALM B., HEILIG M. Anxiolytic-like action of centrally administered galanin. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;164:17–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90846-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOADO R.J., WU D., WINDISCH M. In vivo upregulation of the blood–brain barrier GLUT1 glucose transporter by brain-derived peptides. Neurosci. Res. 1999;34:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS B.R., SUFIT R.L., MONTGOMERY G.K., BEAULIEU D.A., ERICKSON L.M. Intravenous thyrotropin-releasing hormone in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dose–response and randomized concurrent placebo-controlled pilot studies. Neurol. Clin. 1987;5:143–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWNE S.E., MUIR J.L., ROBBINS T.W., PAGE K.J., EVERITT B.J., MCCULLOCH J. The cerebral metabolic effects of manipulating glutamatergic systems within the basal forebrain in conscious rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:649–663. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CACABELOS R., ALVAREZ A., FENANDEZ-NOVOA L., LOMBARDI VR. A pharmacogenomic approach to Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2000;176:12–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASSONE V.M., ROBERTS M.H., MOORE R.Y. Effects of melatonin on 2-deoxy-[1-14C]glucose uptake within rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Am. J. Physiol. 1988;255:R332–R337. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.2.R332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUNTS S.E., PEREZ S.E., KAHL U., BARTFAI T., BOWSER R.P., DEECHER D.C., MASH D.C., CRAWLEY J.N., MUFSON E.J. Galanin: neurobiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential for Alzheimer's disease. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7:445–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAWLEY J.N. Biological actions of galanin. Regul. Peptides. 1995;59:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(95)00083-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROMER B.A., MORTON C.J., PARKER M.W. Anxiety over GABA(A) receptor structure relieved by AChBP. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:280–287. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANIELL L.C. Effect of anesthetic and convulsant barbiturates on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated calcium flux in brain membrane vesicles. Pharmacology. 1994;49:296–307. doi: 10.1159/000139246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE REUCK J., VAN VLEYMEN B. The clinical safety of high-dose piracetam – its use in the treatment of acute stroke. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1999;32 Suppl 1:33–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVINSKY O., ELGER C. Efficacy of levetiracetam in partial seizures. Epileptic Disord. 2003;5 Suppl 1:S27–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DWYER D.S., PINKOFSKY H.B., LIU Y., BRADLEY R.J. Antipsychotic drugs affect glucose uptake and the expression of glucose transporters in PC12 cells. Prog. Neuro. Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;23:69–80. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(98)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EINTREI C., SOKOLOFF L., SMITH C.B. Effects of diazepam and ketamine administered individually or in combination on regional rates of glucose utilization in rat brain. Br. J. Anaesth. 1999;82:596–602. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.4.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNST M., BRAUCHART D, BORESCH S., SIEGHART W. Comparative modeling of GABAA receptors: limits, insights, future developments. Neuroscience. 2003;119:933–943. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKS B., GILLARD M., MICHEL P., LYNCH B., VERTONGEN P., LEPRINCE P., KLITGAARD H., CHATELAIN P. Localization and photoaffinity labelling of the levetiracetam binding site in rat brain and certain cell lines. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;478:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAUS S.E., STRECKER R.E., TATE B.A., PARKER R.A., SAPER C.B. Ventrolateral preoptic nucleus contains sleep-active, galaninergic neurons in multiple mammalian species. Neuroscience. 2002;115:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GENTON P., GUERRINI R., REMY C. Piracetam in the treatment of cortical myoclonus. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1999;32 Suppl I:49–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERMANN P., LAHER I., POSENO T., BEVAN J.A. Barbiturate attenuation of agonist affinity in cerebral arteries correlates with anesthetic potency and lipid solubility. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1994;72:963–969. doi: 10.1139/y94-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHELARDINI C., GALEOTTI N., GUALTIERI F., ROMANELLI M.N., BUCHERELLI C., BALDI E., BARTOLINI A. DM235 (sunifiram): a novel nootropic with potential as a cognitive enhancer. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2002;365:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0577-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLARD M., FUKS B., MICHEL P., VERTONGEN P., MASSINGHAM R., CHATELAIN P. Binding characteristics of [3H]ucb 30889 to levetiracetam binding sites in rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;478:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GJEDDE A., RASMUSSEN M. Pentobarbital anesthesia reduces blood–brain glucose transfer in the rat. J. Neurochem. 1980;35:1382–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb09013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOULIAEV A.H., SENNING A. Piracetam and other structurally related nootropics. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1994;19:180–222. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOWER A.J., NOYER M., VERLOES R., GOBERT J., WULFERT E. ucb L059, a novel anti-convulsant drug: pharmacological profile in animals. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;222:193–203. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90855-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUDASHEVA T.A., KONSTANTINOPOL'SKII M.A., OSTROVSKAYA R.U., SEREDENIN S.B. Anxiolytic activity of endogenous nootropic dipeptide cycloprolylglycine in elevated plus-maze test. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2001;131:464–466. doi: 10.1023/a:1017928116025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARIK S.I., KALARIA R.N. Blood–brain barrier abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1991;640:47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASPEL H.C., STEPHENSON K.N., DAVIES-HILL T., EL BARBARY A., LOBO J.F., CROXEN R.L., MOUGRABI W., KOEHLER-STEC E.M., FENSTERMACHER J.D., SIMPSON I.A. Effects of barbiturates on facilitative glucose transporters are pharmacologically specific and isoform selective. J. Membr. Biol. 1999;169:45–53. doi: 10.1007/pl00005900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEISS W.D., HEBOLD I., KLINKHAMMER P., ZIFFLING P., SZELIES B., PAWLIK G., HERHOLZ K. Effect of piracetam on cerebral glucose metabolism in Alzheimer's disease as measured by positron emission tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8:613–617. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEISS W.D., HERHOLZ K., PAWLIK G., HEBOLD I., KLINKHAMMER P., SZELIES B. Positron emission tomography findings in dementia disorders: contributions to differential diagnosis and objectivizing of therapeutic effects. Keio J. Med. 1989;38:111–135. doi: 10.2302/kjm.38.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HINKLE P.M., PEKARY A.E., SENANAYAKI S., SATTIN A. Role of TRH receptors as possible mediators of analeptic actions of TRH-like peptides. Brain Res. 2002;935:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRAI T., HEYMANN J.A., MALONEY P.C., SUBRAMANIAM S. Structural model for 12-helix transporters belonging to the major facilitator superfamily. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:1712–1718. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1712-1718.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORITA A. An update on the CNS actions of TRH and its analogs. Life Sci. 1998;62:1443–1448. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOVINGA C.A. Levetiracetam: a novel antiepileptic drug. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:1375–1388. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.17.1375.34432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATSUMATA T., KATAYAMA Y., YONEMORI H., MURAMATSU H., OTORI T., NISHIYAMA Y., YAMADA H., NAKAMURA H., TERASHI A. Delayed administration of JTP-2942, a novel thyrotropin-releasing hormone analogue, improves cerebral blood flow and metabolism in rat postischaemic brain. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2001;28:48–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLY P.A., FORD I., MCCULLOCH J. The effect of diazepam upon local cerebral glucose use in the conscious rat. Neuroscience. 1986;19:257–265. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHAN N., HAJEK M., ANTONINI A., MAGUIRE P., MULLER S., VALAVANIS A., LEENDERS K.L., REGARD M., SCHIESS R., WIESER H.G. Cerebral metabolic changes (18F-FDG PET) during selective anterior temporal lobe amobarbital test. Eur. Neurol. 1997;38:268–275. doi: 10.1159/000113393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINNEY J.W., STAROSTA G., CRAWLEY J.N. Central galanin administration blocks consolidation of spatial learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2003;80:42–54. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINOSHITA K., WATANABE Y., ASAI H., YAMAMURA M., MATSUOKA Y. Anti-ataxic effects of TRH and its analogue, TA-0910, in rolling mouse Nagoya by metabolic normalization of the ventral tegmental area. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:3274–3278. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEPPER J., FLORCKEN A., FISCHBARG J., VOIT T. Effects of anticonvulsants on GLUT1-mediated glucose transport in GLUT1 deficiency syndrome in vitro. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003;162:84–89. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-1112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNAPP R.J., GOLDENBERG R., SHUCK C., CECIL A., WATKINS J., MILLER C., CRITES G., MALATYNSKA E. Antidepressant activity of memory-enhancing drugs in the reduction of submissive behavior model. Eur. J.Pharmacol. 2002;440:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLTCHINE V.V., YE Q., FINN S.E., HARRISON N.L. Chimeric GABAA/glycine receptors: expression and barbiturate pharmacology. Neuropharmacol. 1996;35:1445–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOSKINIEMI M., VAN VLEYMEN B., HAKAMIES L., LAMUSUO S., TAALAS J. Piracetam relieves symptoms in progressive myoclonus epilepsy: a multicentre, randomised, double blind, crossover study comparing the efficacy and safety of three dosages of oral piracetam with placebo. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 1998;64:344–348. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAMPFL K., SCHLESINGER F., DENGLER R., BUFLER J., KLAUS K., FRIEDRICH S., REINHARDT D. Pentobarbital has curare-like effects on adult-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel currents. Anesthes. Analg. 2000;90:970–974. doi: 10.1213/00000539-200004000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY J.P., FILLENZ M. Real-time monitoring of brain energy metabolism in vivo using microelectrochemical sensors: the effects of anesthesia. Bioelectrochemistry. 2001;54:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5394(01)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSZALEC W., NARAHASHI T. Use-dependent pentobarbital block of kainate and quisqualate currents. Brain Res. 1993;608:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90766-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCGEER P.L., KAMO H., HARROP R., MCGEER E.G., MARTIN W.R., PATE B.D., LI D.K. Comparison of PET, MRI, and CT with pathology in a proven case of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1986;36:1569–1574. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.12.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIELKE R., PIETRZYK U., JACOBS A., FINK G.R., ICHIMIYA A., KESSLER J., HERHOLZ K., HEISS W.D. HMPAO SPET and FDG PET in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia: comparison of perfusion and metabolic pattern. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1994;21:1052–1060. doi: 10.1007/BF00181059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLNAR P., GAAL L., HORVATH C. The impairment of long-term potentiation in rats with medial septal lesion and its restoration by cognition enhancers. Neurobiology (Bp) 1994;2:255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORZORATI S., KUBEK M.J. The effect of TRH on ethanol-induced sedation in alcohol-preferring and -nonpreferring rats. Neuropeptides. 1993;25:283–287. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(93)90045-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOYERSOONS F., GIURGEA C.E. Protective effect of piracetam in experimental barbiturate intoxication: EEG and behavioural studies. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1974;210:38–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUFSON E.J., IKONOMOVIC M.D., STYREN S.D., COUNTS S.E., WUU J., LEURGANS S., BENNETT D.A., COCHRAN E.J., DEKOSKY S.T. Preservation of brain nerve growth factor in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60:1143–1148. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUECKLER M., MAKEPEACE C. Analysis of transmembrane segment 8 of the GLUT1 glucose transporter by cysteine-scanning mutagenesis and substituted cysteine accessibility. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10494–10499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUECKLER M., CARUSO C., BALDWIN S.A., PANICO M., BLENCH I., MORRIS H.R., ALLARD W.J., LIENHARD G.E., LODISH H.F. Sequence and structure of a human glucose transporter. Science. 1985;229:941–945. doi: 10.1126/science.3839598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLER W.E., KOCH S., SCHEUER K., ROSTOCK A., BARTSCH R. Effects of piracetam on membrane fluidity in the aged mouse, rat, and human brain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997;53:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAFTALIN R.J.Glucose transport Red Cell Membrane Transport in Health and Disease 2003Berlin: Springer; 339–365.ed. Bernhardt, I. & Clive Ellory, J. pp [Google Scholar]

- NAFTALIN R.J., AFZAL I., CUNNINGHAM P., HALAI M., ROSS C., SALLEH N., MILLIGAN S.R. Interactions of androgens, green tea catechins and the antiandrogen flutamide with the external glucose-binding site of the human erythrocyte glucose transporter GLUT1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;140:487–499. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAFTALIN R.J., ARAIN M. Interactions of sodium pentobarbital with D-glucose and L-sorbose transport in human red cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1419:78–88. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASH E.M., SANGHA K.S. Levetiracetam. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharmacol. 2001;58:1195–1199. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.13.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIZAKI T., MATSUOKA T., NOMURA T., SUMIKAWA K., SHIOTANI T., WATABE S., YOSHII M. Nefiracetam modulates acetylcholine receptor currents via two different signal transduction pathways. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:1–5. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOYER M., GILLARD M., MATAGNE A., HENI ., WULFERT E. The novel antiepileptic drug levetiracetam (ucb L059) appears to act via a specific binding site in CNS membranes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;286:137–146. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00436-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NUGENT M., ARTRU A.A., MICHENFELDER J.D. Cerebral metabolic, vascular and protective effects of midazolam maleate: comparison to diazepam. Anesthesiology. 1982;56:172–176. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OGASAWARA T., UKAI Y., TAMURA M., KIMURA K. NS-3 (CG3703), an analog of thyrotropin-releasing hormone, ameliorates cognitive impairment in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1995;50:499–503. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSTROVSKAIA R.U., LIAPINA L.A., PASTOROVA V.E., MIRZOEV T.K., GUDASHEVA T.A., SEREDENIN S.B., ASHMARIN I.P. Multicomponent antithrombotic effect of the neuroprotective prolyl dipeptide GVS-111 and its major metabolite cyclo-L-prolylglycine] Eksp. Klin. Farmakol. 2002;65:34–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OTSUKA T., WEI L., BERECZKI D., ACUFF V., PATLAK C., FENSTERMACHER J. Pentobarbital produces dissimilar changes in glucose influx and utilization in brain. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;261:R265–R275. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.2.R265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARSON W.R., LIPMAN D.J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POULAIN P., MARGINEANU D.G. Levetiracetam opposes the action of GABAA antagonists in hypothalamic neurones. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:346–352. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRANZATELLI M.R. Myoclonic disorders. Antimyoclonic drug sites and mechanisms of action. Drugs Today (Barc.) 1997;33:315–324. [Google Scholar]

- PRASAD C. Bioactive cyclic dipeptides. Peptides. 1995;16:151–164. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)00017-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REIMAN E.M., CHEN K., ALEXANDER G.E., CASELLI R.J., BANDY D., OSBORNE D., SAUNDERS A.M., HARDY J. Functional brain abnormalities in young adults at genetic risk for late-onset Alzheimer's dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:284–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2635903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIGO J.M., HANS G., NGUYEN L., ROCHER V., BELACHEW S., MALGRANGE B., LEPRINCE P., MOONEN G., SELAK I., MATAGNE A., KLITGAARD H. The anti-epileptic drug levetiracetam reverses the inhibition by negative allosteric modulators of neuronal. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:659–672. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROZHANETS V.V., CHAKHBRA K.K., DANCHEV N.D., MALIN K.M., RUSAKOV D.I. Interaction of piracetam with 3H-imipramine binding sites and the GAMA-benzodiazepine receptor complex of brain membranes. Bull. Eksp. Biol. Med. 1986;101:40–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUCZYNSK J., CYBAL M., WOJCIKOWSKIB C., REKOWSKI P. Effects of porcine galanin, galanin(1–15)NH2 and its new analogues on glucose-induced insulin secretion. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2002;54:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUETHER E., ALVAREZ X.A., RAINER M., MOESSLER H. Sustained improvement of cognition and global function in patients with moderately severe Alzheimer's disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study with the neurotrophic agent cerebrolysin. J. Neural Trans. Suppl. 2002;62:265–275. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6139-5_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALIMOV R., SALIMOVA N., SHVETS L., SHVETS N. Explorative and drinking behavior after prolonged access to alcohol and following chronic piracetam administration in mice. Alcohol. 1995;12:485–489. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANTENS P., DE BLEECKER J., GOETHALS P., STRIJCKMANS K., LEMAHIEU I., SLEGERS G., DIERCKX R., DE REUCK J. Differential regional cerebral uptake of (18)F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia at initial diagnosis. Eur. Neurol. 2001;45:19–27. doi: 10.1159/000052084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEN A.K., WIDDAS W.F. Determination of the temperature and pH dependence of glucose transfer across the human erythrocyte membrane measured by glucose exit. J. Physiol. 1962;160:392–403. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEREDENIN S.B., GUDASHEVA T.A., BOIKO S.S., KOVALEV G.I., VORONIN M.V., YARKOVA M.A. Endogenous dipeptide cycloprolylglycine shows selective anxiolytic activity in animals with manifest fear reaction. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2002;133:360–362. doi: 10.1023/a:1016293904149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARP T., TULLOCH I.F., BENNETT G.W., MARSDEN C.A., METCALF G., DETTMAR P.W. Analeptic effects of centrally injected TRH and analogues of TRH in the pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rat. Neuropharmacology. 1984;23:339–348. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(84)90197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIEMKOWICZ E. Improvement of restitution from cerebral ischemia in hyperglycemic rats by pentobarbital or diazepam. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1980;61:368–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1980.tb01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGEL E. Mapping of the benzodiazepine recognition site on GABA(A) receptors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002;2:833–839. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH G.B., OLSEN R.W. Functional domains of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995;16:162–168. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH T.F., WATERMAN M.S. Identification of common molecular subsequences J. Mol. Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPIGNOLI G., MAGNANI M., GIOVANNINI M.G., PEPEU G. Effect of pyroglutamic acid stereoisomers on ECS and scopolamine-induced memory disruption and brain acetylcholine levels in the rat. Pharmacol. Res. Commun. 1987;19:901–912. doi: 10.1016/0031-6989(87)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPIGNOLI G., PEPEU G. Interactions between oxiracetam, aniracetam and scopolamine on behavior and brain acetylcholine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1987;27:491–495. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEFANI M.R., GOLD P.E. Intra-septal injections of glucose and glibenclamide attenuate galanin-induced spontaneous alternation performance deficits in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;813:50–56. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINER R.A., HOHMANN J.G., HOLMES A., WRENN C.C., CADD G., JUREUS A., CLIFTON D.K., LUO M., GUTSHALL M., MA S.Y., MUFSON E.J., CRAWLEY J.N. Galanin transgenic mice display cognitive and neurochemical deficits characteristic of Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:4184–4189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061445598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEPHENSON K.N., CROXEN R.L., EL BARBARY A., FENSTERMACHER J.D., HASPEL H.C. Inhibition of glucose transport and direct interactions with type 1 facilitative glucose transporter (GLUT-1) by etomidate, ketamine, and propofol: a comparison with barbiturates. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;60:651–659. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGDEN D., DAVIES D.J., GARRATT P.J., JONES R., VONHOFF S. Radioligand binding affinity and biological activity of the enantiomers of a chiral melatonin analogue. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;287:239–243. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON S.A., WHITING P.J., WAFFORD K.A. Barbiturate interactions at the human GABAA receptor: dependence on receptor subunit combination. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:521–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VRONTAKIS M.E. Galanin: a biologically active peptide. Curr. Drug Target CNS Neurol. Disord. 2002;1:531–541. doi: 10.2174/1568007023338914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLNER M., HANCHAR H.J., OLSEN R.W. Ethanol enhances alpha 4 beta 3 delta and alpha 6 beta 3 delta gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors at low concentrations known to affect humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:15218–15223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435171100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG F., LI J., WU C., YANG J., XU F., ZHAO Q. The GABA(A) receptor mediates the hypnotic activity of melatonin in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003;74:573–578. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZUNIGA F.A., SHI G., HALLER J.F., RUBASHKIN A., FLYNN D.R., ISEROVICH P., FISCHBARG J. A three-dimensional model of the human facilitative glucose transporter Glut1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:44970–44975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]