Abstract

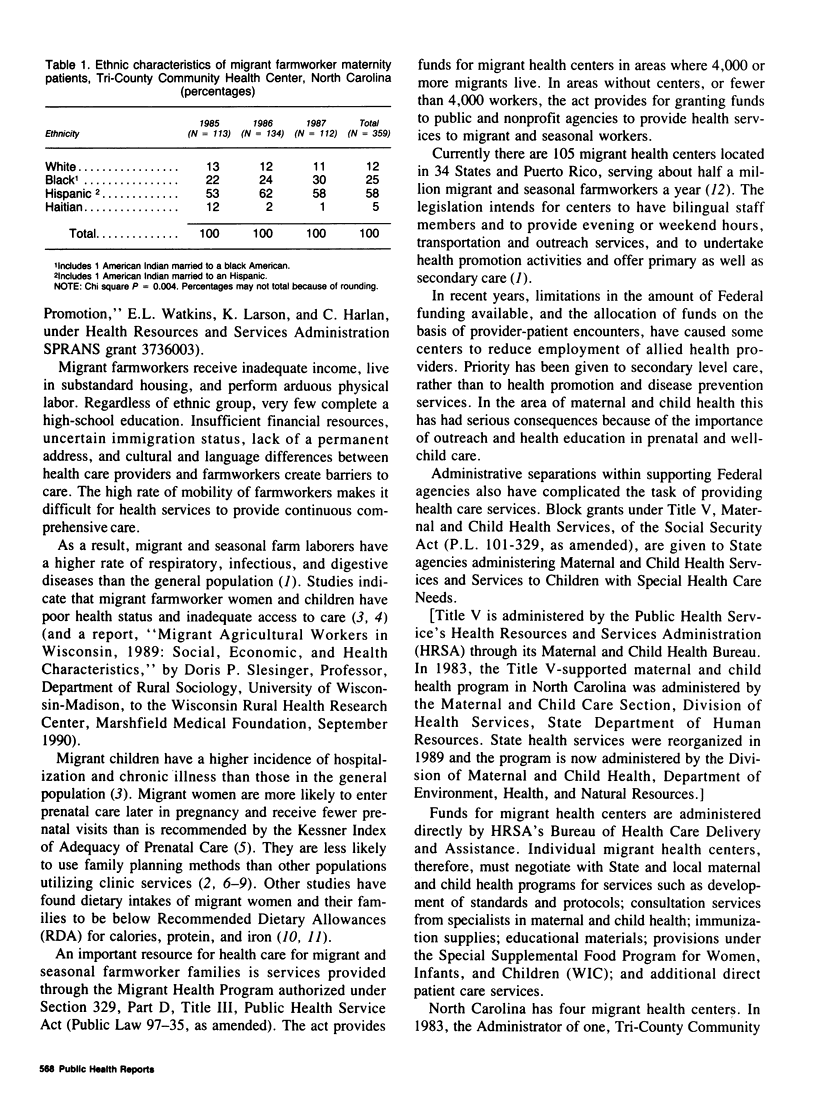

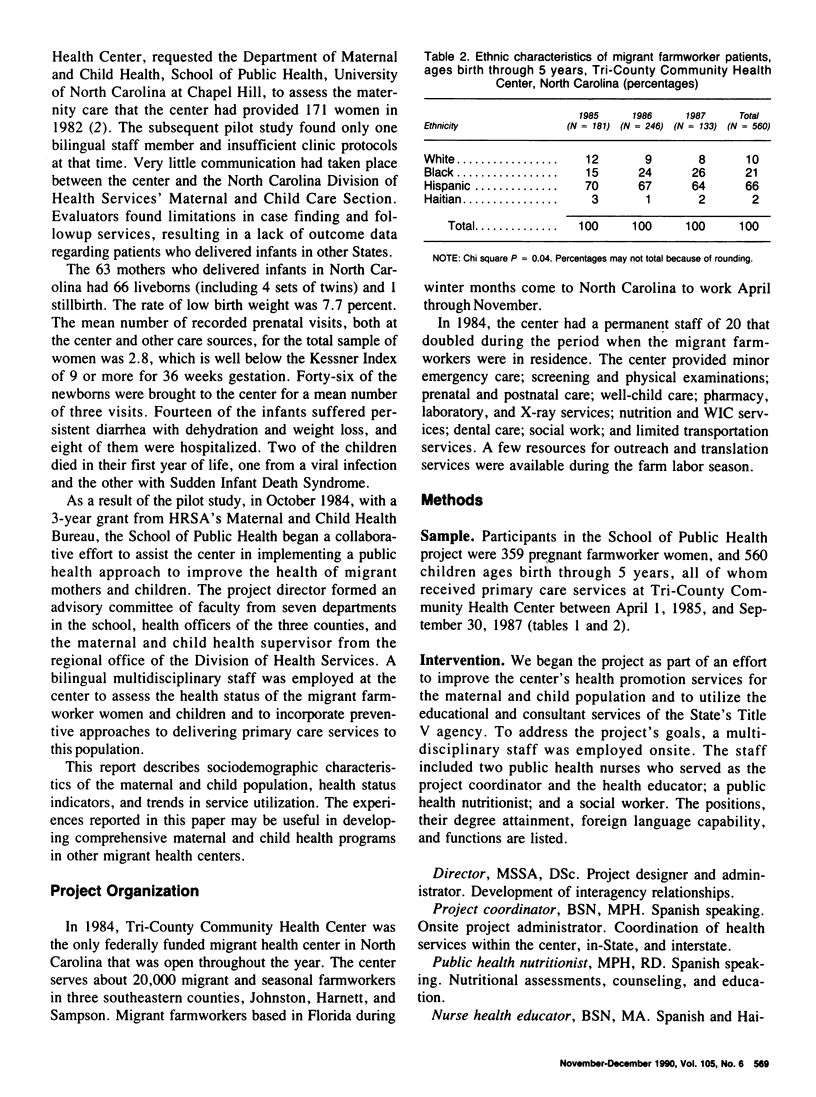

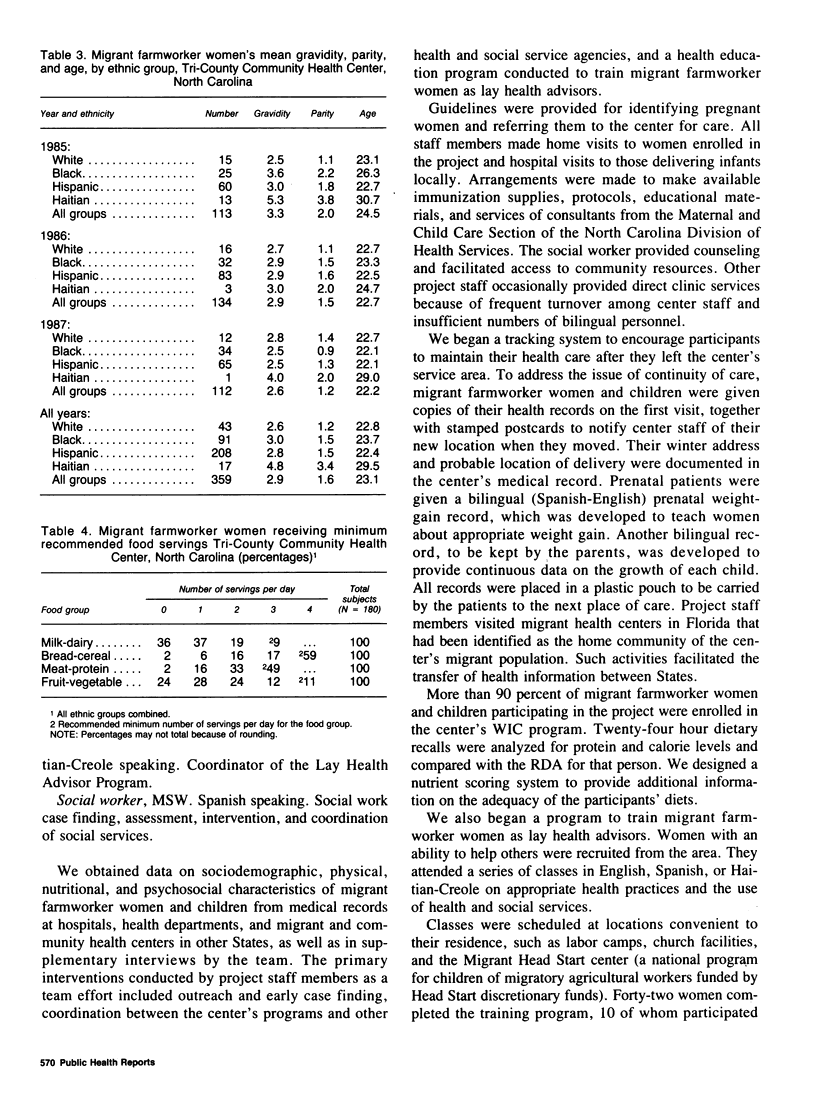

A bilingual, multidisciplinary team of health professionals collaborated with a migrant health center in North Carolina to develop a model program to deliver primary health care services to migrant farmworker women and children. The program included case finding and outreach, coordination of maternal and child health services locally as well as interstate, and innovative health education programming. Data were collected on the health status of 359 pregnant migrant farmworker women and 560 children, ages birth to 5 years, the majority of Mexican descent, who received primary care services at the center. The mean age of the women was 23.1 years and their mean gravidity was 2.9. Dietary assessments showed that the protein intakes of most met or exceeded the U.S. Recommended Dietary Allowances, but their consumption of foods in the milk-dairy group and the fruit-vegetable group was below recommended standards. Low hematocrit was a common problem among the women (43 percent) and, to a lesser extent, among the children (26 percent). Among the infants and children, 18 percent were obese. Black American women had the highest proportion of low birth weight infants. The project emphasized coordinated services for migrant farmworker mothers and children, such as transportation services, language translation, followup, and advocacy. An outreach strategy involved case finding, home visits, and services by lay health advisors. By the third year of the project, there were increases in the average number of prenatal visits, the proportion of women entering prenatal care in their first trimester, and in the use of well-child services.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Acosta P. B., Aranda R. G., Lewis J. S., Read M. Nutritional status of Mexican American preschool children in a border town. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974 Dec;27(12):1359–1368. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/27.12.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas J., Gibbs C. E., Young E. A. Nutritional beliefs and practices in primigravid Mexican-American women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1976 Sep;69(3):262–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase H. P., Kumar V., Dodds J. M., Sauberlich H. E., Hunter R. M., Burton R. S., Spalding V. Nutritional status of preschool Mexican-American migrant farm children. Am J Dis Child. 1971 Oct;122(4):316–324. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1971.02110040100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez L. R., Cornelius W. A., Jones O. W. Utilization of health services by Mexican immigrant women in San Diego. Women Health. 1986 Summer;11(2):3–20. doi: 10.1300/J013v11n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen P. J., Ezzati T., Russell H. DTP immunization status and tetanus antitoxin titers of Mexican American children ages six months through eleven years. Am J Public Health. 1988 Nov;78(11):1446–1450. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.11.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S., Schwalbe J. Medical care utilization by Hispanic children. How does it differ from black and white peers? Med Care. 1986 Oct;24(10):925–940. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M. S. A migrant referral system for continuity of health care. Nurs Clin North Am. 1972 Mar;7(1):133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson L. B., Dodds J. M., Massoth D. M., Chase H. P. Nutritional status of children of Mexican-American migrant families. J Am Diet Assoc. 1974 Jan;64(1):29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield C., Stout C. L. A survey of Colorado's migrant farmworkers: access to health care. Int Migr Rev. 1987 Fall;21(3):688–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina A. S. Hispanic maternity care: a study of deficiencies and recommended policies. Public Aff Rep. 1980 Apr;21(2):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowski M., Reid P. R., Mower M. M., Watkins L., Jr, Platia E. V., Griffith L. S., Veltri E. P., Guarnieri T., Juanteguy J. M. Clinical experience with the automatic implantable defibrillator. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1985 Oct;78(Spec No):39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinger D. P., Christenson B. A., Cautley E. Health and mortality of migrant farm children. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura S. J., Taffel S. M. Childbearing characteristics of U.S.- and foreign-born Hispanic mothers. Public Health Rep. 1985 Nov-Dec;100(6):647–652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanochik-Owen A., White M. Nutrition surveillance in Arizona: selected anthropometric and laboratory observations among Mexican-American children. Am J Public Health. 1977 Feb;67(2):151–154. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S. A., Kaufman M. Promoting breastfeeding at a migrant health center. Am J Public Health. 1988 May;78(5):523–525. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.5.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]