Abstract

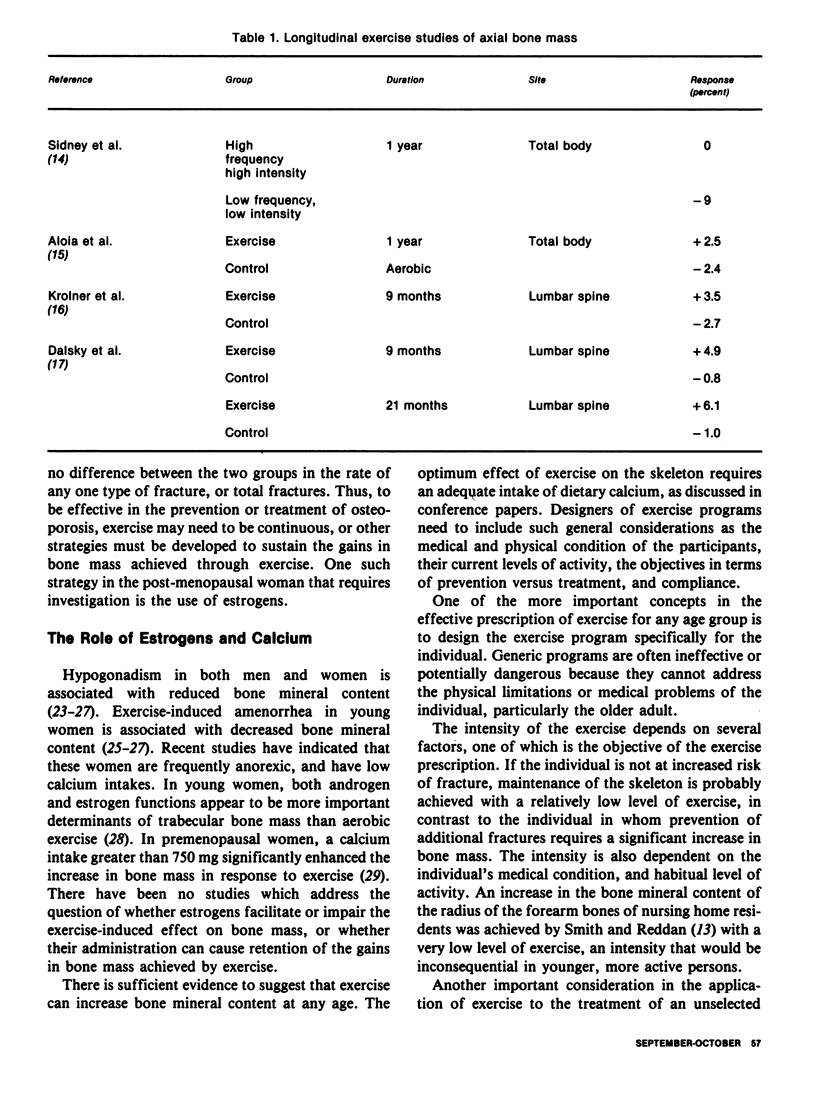

Evidence from a variety of sources indicates that exercise can increase the mineral content of bone, raising the expectation that exercise programs may be effective therapy for the treatment of osteoporosis, and the prevention of hip and spinal fractures. Indeed, prospective studies demonstrate that primarily weight-bearing exercise prevents the age-related decline in axial skeletal mass and, in some instances, increases bone mineral content. Optimal changes in the skeleton in response to exercise are seen in those women with adequate intake of dietary calcium. Neither hormonal status nor age appears to preclude the skeletal benefits of exercise. The design of an exercise program must consider the physical condition of the participants, their current levels of activity, their compliance, and the objectives of the program. Generic programs that are not designed for individuals' needs and limitations, and that are not adequately supervised, will result in a high rate of musculoskeletal complications and noncompliance. Unfortunately, additional studies are necessary before we can construct an optimum exercise prescription for bone health which addresses duration, frequency, intensity, and type of exercise. Of concern is the fact that gains in bone mass achieved with exercise are lost following their discontinuation in postmenopausal women, underscoring the concept that the level of physical activity is a major and dynamic determinant of skeletal integrity. Thus, it will be necessary to develop strategies to preserve the gains in skeletal mass achieved through exercise. Finally, before exercise can be promoted for bone health, it will be necessary to demonstrate that such programs can indeed prevent osteoporotic fractures.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aloia J. F., Cohn S. H., Babu T., Abesamis C., Kalici N., Ellis K. Skeletal mass and body composition in marathon runners. Metabolism. 1978 Dec;27(12):1793–1796. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(78)90265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloia J. F., Cohn S. H., Ostuni J. A., Cane R., Ellis K. Prevention of involutional bone loss by exercise. Ann Intern Med. 1978 Sep;89(3):356–358. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-3-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer V., Meyer B. M., Keele M. S., Upton S. J., Hagan R. D. Role of exercise in prevention of involutional bone loss. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1983;15(6):445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan J. R., Myers C., Lloyd T., Leuenberger P., Demers L. M. Determinants of peak trabecular bone density in women: the role of androgens, estrogen, and exercise. J Bone Miner Res. 1988 Dec;3(6):673–680. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650030613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann C. E., Martin M. C., Genant H. K., Jaffe R. B. Decreased spinal mineral content in amenorrheic women. JAMA. 1984 Feb 3;251(5):626–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter D. R. Mechanical loading histories and cortical bone remodeling. Calcif Tissue Int. 1984;36 (Suppl 1):S19–S24. doi: 10.1007/BF02406129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamay A., Tschantz P. Mechanical influences in bone remodeling. Experimental research on Wolff's law. J Biomech. 1972 Mar;5(2):173–180. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(72)90053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn S. H., Vaswani A., Zanzi I., Aloia J. F., Roginsky M. S., Ellis K. J. Changes in body chemical composition with age measured by total-body neutron activation. Metabolism. 1976 Jan;25(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(76)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalén N., Olsson K. E. Bone mineral content and physical activity. Acta Orthop Scand. 1974;45(2):170–174. doi: 10.3109/17453677408989136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drinkwater B. L., Nilson K., Ott S., Chesnut C. H., 3rd Bone mineral density after resumption of menses in amenorrheic athletes. JAMA. 1986 Jul 18;256(3):380–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H. H., Priest J. D., Hayes W. C., Tichenor C. C., Nagel D. A. Humeral hypertrophy in response to exercise. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977 Mar;59(2):204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krølner B., Toft B., Pors Nielsen S., Tøndevold E. Physical exercise as prophylaxis against involutional vertebral bone loss: a controlled trial. Clin Sci (Lond) 1983 May;64(5):541–546. doi: 10.1042/cs0640541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R., Cann C., Madvig P., Minkoff J., Goddard M., Bayer M., Martin M., Gaudiani L., Haskell W., Genant H. Menstrual function and bone mass in elite women distance runners. Endocrine and metabolic features. Ann Intern Med. 1985 Feb;102(2):158–163. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-2-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R., Hegenauer J., Saltman P. Age-related differences in the bone mineralization pattern of rats following exercise. J Gerontol. 1986 Jul;41(4):445–452. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey E. R., Baylink D. J. Inhibition of bone formation during space flight. Science. 1978 Sep 22;201(4361):1138–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.150643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson B. E., Westlin N. E. Bone density in athletes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1971;77:179–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLUM F., DUNNING M. F. The effect of therapeutic mobilization on hypercalciuria following acute poliomyelitis. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1958 Mar;101(3):528–536. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1958.00260150016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock N. A., Eisman J. A., Yeates M. G., Sambrook P. N., Eberl S. Physical fitness is a major determinant of femoral neck and lumbar spine bone mineral density. J Clin Invest. 1986 Sep;78(3):618–621. doi: 10.1172/JCI112618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs B. L., Eastell R. Exercise, hypogonadism, and osteopenia. JAMA. 1986 Jul 18;256(3):392–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti N. A., Neer R. M., Jameson L. Osteopenia and bone fractures in a man with anorexia nervosa and hypogonadism. JAMA. 1986 Jul 18;256(3):385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin C. T., Lanyon L. E. Regulation of bone formation by applied dynamic loads. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984 Mar;66(3):397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidney K. H., Shephard R. J., Harrison J. E. Endurance training and body compostition of the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977 Mar;30(3):326–333. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin A., Ayalon J., Leichter I. Increased trabecular bone density due to bone-loading exercises in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Calcif Tissue Int. 1987 Feb;40(2):59–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02555706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. L., Reddan W. Proceedings: Physical activity--a modality for bone accretion in the aged. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976 Jun;126(6):1297–1297. doi: 10.2214/ajr.126.6.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyshak G., Frisch R. E., Albright T. E., Albright N. L., Schiff I. Bone fractures among former college athletes compared with nonathletes in the menopausal and postmenopausal years. Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Jan;69(1):121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]