Abstract

During ribosome biogenesis, the RNA precursor to mature rRNAs undergoes numerous post-transcriptional chemical modifications of bases, including conversions of uridines to pseudouridines. In archaea and eukaryotes, these conversions are performed by box H/ACA small ribonucleoprotein particles (box H/ACA RNPs), which contain a small guide RNA responsible for the selection of substrate uridines and four proteins, including the pseudouridine synthase, Cbf5p. So far, no in vitro reconstitution of eukaryotic box H/ACA RNPs from purified components has been achieved, principally due to difficulties in purifying recombinant eukaryotic Cbf5p. In this study, we present the purification of a truncated derivative of yeast Cbf5p (Cbf5Δp) that retains the highly conserved TRUB and PUA domains. We have used band retardation assays to show that Cbf5Δp on its own binds to box H/ACA small nucleolar (sno)RNAs. We demonstrate that the conserved H and ACA boxes enhance the affinity of the protein for the snoRNA. Furthermore, like its archaeal homologs, Cbf5Δp can bind to a single stem–loop-box ACA RNA. Finally, we report the first enzymatic footprinting analysis of a Cbf5–RNA complex. Our results are compatible with the view that two molecules of Cbf5p interact with a binding platform constituted by the 5′ end of the RNA, the single-stranded hinge domain containing the conserved H box, and the 3′ end of the molecule, including the conserved ACA box.

Keywords: box H/ACA snoRNP, box H/ACA snoRNA, rRNA pseudouridylation, yeast Cbf5p, RNA–protein interactions

INTRODUCTION

Pseudouridine is the most frequent and universally found modified nucleoside in RNA (Charette and Gray 2000; Ofengand et al. 2001). Numerous pseudouridine residues are present at specific positions in rRNAs and tRNAs from archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes and in some snRNAs in eukaryotes. Some of these modifications are important for the activity of RNAs in translation and splicing reactions (King et al. 2003; Donmez et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2005). Pseudouridine residues in RNAs are formed post-transcriptionally by a group of enzymes called pseudouridine synthases (Ferré-D'Amaré 2003). Either a single protein has the specific RNA modification activity or the activity is found within a ribonucleoprotein complex and pseudouridylation is achieved by an RNA-guided mechanism. In archaea and eukaryotic cells, so-called box H/ACA small ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs) mediate site-specific pseudouridylation of diverse RNAs (Henras et al. 2004b; Meier 2005). In eukaryotes, most of these particles are localized in the nucleolus, hence their name, box H/ACA small nucleolar (sno)RNPs, and they are involved in pseudouridylation of rRNAs (Ganot et al. 1997a; Ni et al. 1997), while a subset are required for certain cleavage events during maturation of pre-rRNAs (Tollervey 1987; Morrissey and Tollervey 1993; Atzorn et al. 2004). A recently discovered group of H/ACA particles accumulating in Cajal bodies, therefore termed small Cajal body specific (sca)RNPs, has been shown to direct the pseudouridylation of spliceosomal snRNAs transcribed by RNA pol II (Darzacq et al. 2002; Richard et al. 2003). Surprisingly, mammalian telomerase, a RNA–protein enzyme that catalyzes telomere addition, is related to box H/ACA RNPs (Mitchell et al. 1999a,b; Chen et al. 2000; Dragon et al. 2000; Pogacic et al. 2000; Dez et al. 2001; Henras et al. 2003; Chen and Greider 2004; Wang and Meier 2004), although it probably does not function in pseudouridylation.

Box H/ACA RNPs contain a small box H/ACA RNA and a common set of proteins. The majority of eukaryotic box H/ACA RNAs feature two hairpins of variable length separated by a single-stranded region that includes a conserved H box (5′-ANANNA-3′) (Ganot et al. 1997b) and followed by a short tail containing an ACA trinucleotide (Balakin et al. 1996). The 5′ and 3′ hairpins each possess an internal loop, termed the pseudouridylation pocket (Ganot et al. 1997a). In archaea, several “H/ACA” small RNAs are constituted of a single hairpin with a pseudouridylation pocket and a 3′ single-stranded region containing the ACA box (Tang et al. 2002; Rozhdestvensky et al. 2003). Box H/ACA RNAs involved in pseudouridylation select the uridines that will undergo isomerization to pseudouridine by establishing base-pairing interactions between short sequences within their pseudouridylation pockets and target RNAs (Ganot et al. 1997a). Four proteins have been identified as components of H/ACA RNPs: Cbf5p (dyskerin in humans, Nap57 in rodents, Nop60B in Drosophila) (Meier and Blobel 1994; Lafontaine et al. 1998; Phillips et al. 1998; Watkins et al. 1998; Mitchell et al. 1999b; Yang et al. 2000), Gar1p (Girard et al. 1992; Balakin et al. 1996; Ganot et al. 1997b; Dragon et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2000), Nhp2p (Henras et al. 1998; Watkins et al. 1998; Pogacic et al. 2000), and Nop10p (Henras et al. 1998; Pogacic et al. 2000). The archaeal orthologs are aCbf5, aGar1, L7Ae, and aNop10, respectively (Watanabe and Gray 2000; Rozhdestvensky et al. 2003). In yeast, all four proteins have been shown to be essential for viability and depletion of Cbf5p, Nhp2p, or Nop10p impairs the accumulation of other components of H/ACA snoRNPs (Henras et al. 1998, 2004a; Lafontaine et al. 1998). In contrast, when Gar1p is absent, residual box H/ACA snoRNPs are stable but no longer associated with pre-rRNAs (Bousquet-Antonelli et al. 1997). Cbf5p is a member of the TruB family (Koonin 1996), which includes pseudouridine synthases catalyzing isomerization of uridine 55 in most tRNAs. Modifications of highly conserved amino acids in the pseudouridine synthase domain of Cbf5p abolish in vivo pseudouridylation of rRNAs (Zebarjadian et al. 1999). Thus, Cbf5p is clearly the modifying enzyme in H/ACA RNPs.

Recent work in the field has focused on the structure of components of H/ACA RNPs and on their mode of assembly to yield functional particles. Active archaeal H/ACA RNPs have been reconstituted using in vitro transcribed RNAs and recombinant proteins produced in Escherichia coli (Baker et al. 2005; Charpentier et al. 2005). Such in vitro studies have demonstrated that L7Ae and aCbf5 both bind independently and specifically to distinct sites on the guide RNA (Rozhdestvensky et al. 2003; Baker et al. 2005; Charpentier et al. 2005). The recently solved crystal structures of aCbf5 in complex with aNop10 (Hamma et al. 2005; Manival et al. 2006) or with aNop10 and aGar1 (Rashid et al. 2006) show that aCbf5 shares two major structural domains with TruB, the catalytic domain and the PUA domain, but also that it contains an N-terminal tail absent in TruB. These structures also show that aGar1 and aNop10 interact with the catalytic domain of aCbf5 (Hamma et al. 2005; Manival et al. 2006; Rashid et al. 2006). Studies in eukaryotic systems are less advanced, mainly due to difficulties in purifying soluble recombinant eukaryotic Cbf5p/Nap57 and Gar1p. However, experiments performed with purified yeast H/ACA particles assembled in vivo (Henras et al. 2004a) or using mammalian proteins produced by in vitro transcription/translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Wang and Meier 2004) have shown that, like their archaeal counterparts, eukaryotic Nop10p and Gar1p can independently interact with Cbf5p/Nap57. Moreover, Wang and Meier (2004) also demonstrate that in mammals, the interaction between Nap57 and Nop10p is a prerequisite for Nhp2p binding and that the Nap57–Nop10p–Nhp2p core trimer specifically recognizes H/ACA snoRNAs.

In this article, we significantly extend these studies by showing that the recombinant N-terminal conserved domain of yeast Cbf5p, Cbf5Δp, alone is able to bind an H/ACA snoRNA and by analyzing in detail the way Cbf5Δp interacts with this RNA. In particular, we describe the first footprinting analysis of the interactions of a Cbf5 protein with RNA. Our data indicate that Cbf5Δp interacts primarily with the 5′ end of the RNA, the single-stranded hinge domain containing the conserved H box and the 3′ end of the molecule, including the conserved ACA box.

RESULTS

Yeast Cbf5Δp binds directly to box H/ACA snoRNAs

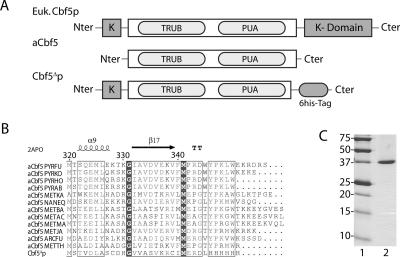

To establish whether yeast Cbf5p can directly bind a box H/ACA snoRNA, we tried to purify the recombinant yeast protein from E. coli. Despite extensive efforts, the full-length recombinant protein could not be produced to sufficient amounts in bacteria, and attempts to produce it in several other systems remained unsuccessful. Thus, we searched for a truncated version of the protein that could be efficiently produced in E. coli and retain most of the properties of wild-type Cbf5p. Sequence alignments of eukaryotic and archaeal Cbf5p orthologs (Fig. 1A) reveal that neither the N-terminal nor the C-terminal lysine-rich domains of eukaryotic proteins are present in the archaeal orthologs. They also reveal a large, highly conserved, central region that encompasses almost the entire archaeal protein and includes the well-defined pseudouridine synthase and PUA domains. Recent reports have shown that purified archaeal aCbf5 assembles in an active H/ACA particle that includes the aGar1 and aNop10 proteins and that these interact directly with aCbf5 via highly conserved residues (Baker et al. 2005; Charpentier et al. 2005; Hamma et al. 2005; Manival et al. 2006; Rashid et al. 2006). This strongly suggests that the conserved central region of yeast Cbf5p retains most of the properties needed to assemble an H/ACA particle.

FIGURE 1.

Purification of Cbf5Δp. (A) Schematic representation of eukaryotic (Euk. Cbf5p) and archaeal (aCbf5) Cbf5p proteins. Alignment of the yeast Cbf5p protein sequence with those of its eukaryotic and archaeal orthologs reveals a large conserved central domain (white box), which contains the catalytic TruB domain and the PUA domain (light gray boxes). The eukaryotic proteins contain additional C-terminal and N-terminal lysine-rich domains (K, dark gray boxes). Yeast Cbf5Δp used in this study lacks the C-terminal lysine-rich domain and retains the first 345 amino acids of the protein. (B) Alignment of the sequence of the C terminus of yeast Cbf5Δp with the corresponding sequences of its archaeal aCbf5 orthologs: aCbf5 PYRFU (Q7LWY0, Pyrococcus furiosus), aCbf5 PYRKO (Q5JJE8, Thermococcus kodakaraensis), aCbf5 PYRHO (O59357, Pyrococcus horikoshii), aCbf5 PYRAB (Q9V1A5, Pyrococcus abyssi), aCbf5 METKA (Q8TZ08, Methanopyrus kandleri), aCbf5 NANEQ (P60346, Nanoarchaeum equitans), aCbf5 METBA (Q46GC3, Methanosarcina barkeri), aCbf5 METAC (Q8TRR5, Methanosarcina acetivorans), aCbf5 METMA (Q8PV20, Methanosarcina mazei), aCbf5 METJA (Q57612, Methanococcus jannaschii), aCbf5 ARCFU (O30001, Archaeoglobus fulgidus), and aCbf5 METTH (O26140, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum). Alignment was performed with the multalin software (Corpet 1988) and edited with ESPript 2.2 (Gouet et al. 2003). Secondary structure elements (PDB accession code: 2APO) from P. furiosus aCbf5 crystallographic data (Hamma et al. 2005) are displayed above the alignment. (C) Coomassie-stained purified recombinant Cbf5Δp protein (lane 2). (Lane 1) Molecular weight protein markers (in kilodaltons).

We therefore assessed whether C-terminal truncated derivatives of yeast Cbf5p that lack the eukaryotic C-terminal lysine-rich domain could be produced in E. coli. Unfortunately, derivative Cbf51–350 (from residues 1–350) that encompasses the entire central conserved domain could not be expressed in bacteria. However, removal of five additional C-terminal residues yields a protein, Cbf51–345 (Cbf5Δp, Fig. 1B,C), that is efficiently produced, although exclusively in an insoluble form in inclusion bodies. Nevertheless, the protein could be purified by Ni-NTA chromatography in denaturing conditions (Materials and Methods). In addition, an exclusion chromatography step was included to separate the monomeric protein from contaminant bacterial peptides and aggregated Cbf5Δp.

We then tested the ability of purified Cbf5Δp to bind an H/ACA snoRNA by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). For this study, we used the well-characterized yeast H/ACA snoRNA snR5 as binding substrate (Parker et al. 1988; Ganot et al. 1997a; Bortolin et al. 1999; Fig. 2A). The in vitro transcribed radiolabeled snR5 was incubated at 25°C with increasing amounts of Cbf5Δp (12.5–1250 nM), and the protein–RNA complexes were separated from unbound RNA on nondenaturating polyacrylamide gels, run at 4°C (Fig. 2B). The snR5 snoRNA (0.125 nM) was completely shifted into a single RNA–protein complex at a Cbf5Δp concentration of 1250 nM (Fig. 2B, lane 8). Similar results were obtained when Cbf5Δp was incubated with yeast snR37 or snR42, two other box H/ACA snoRNAs (data not shown). To assess the specificity of the Cbf5Δp–snR5 interaction, competition experiments were performed. Complexes were assembled with defined amounts of radiolabeled snR5 and Cbf5Δp protein (respectively, 0.125 nM and 625 nM) together with varying amounts of nonlabeled snR5 or U24 (a box C/D snoRNA) as competitors. As shown in Figure 2C, a 1000-fold excess of nonlabeled snR5 impaired Cbf5Δp–snR5 complex formation while the addition of a similar amount of U24 had no effect. These data indicate that Cbf5Δp can directly interact with H/ACA snoRNAs but not with the U24 C/D box snoRNA.

FIGURE 2.

Yeast Cbf5Δp binds directly the snR5 H/ACA snoRNA. (A) Secondary structure model of the snR5 snoRNA as predicted by the mfold software (Zuker 2003). snR5 is a bipartite H/ACA snoRNA composed of 5′ and 3′ stem–loops separated by a single-stranded hinge domain. Conserved H and ACA boxes are highlighted in bold and boxed. Within pseudouridylation pockets, positions that base-pair with 25S rRNA to select the target uridines are highlighted in gray. (B) Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSAs). The in vitro transcribed 32P-labeled snR5 (2.5 fmol) was incubated at 25°C with increasing amounts of purified Cbf5Δp (12.5–1250 nM, lanes 2–8), except in the reaction loaded in lane 1, which lacked Cbf5Δp. (RNP) Cbf5Δp-snR5 complex. (C) Competition experiments were performed with 0.125 nM of 32P-labeled snR5, constant Cbf5Δp concentration (625 nM), and increasing amounts of non-labeled RNA competitors, snR5 (lanes 3–6) or U24 (box C/D snoRNA, lanes 9–12). Molar ratios of competitor RNA versus labeled snR5 are indicated above each lane. (Lanes 1,7) no protein. (Lanes 2,8) no competitor RNA.

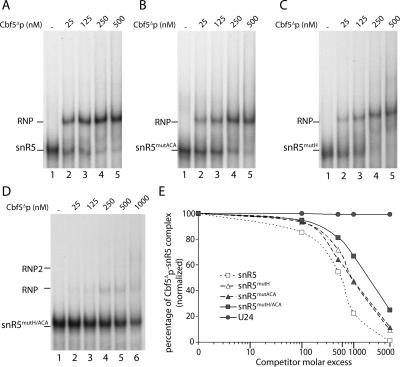

Box H and box ACA both enhance the RNA-binding affinity of Cbf5Δp

To further characterize the Cbf5Δp–snR5 complex, we next asked whether the conserved H box and/or ACA box are required for complex formation. We performed EMSAs with various amounts of purified Cbf5Δp protein and radiolabeled transcripts of either wild-type or modified snR5, snR5mutACA or snR5mutH. In snR5mutACA, the 5′-ACA-3′ box has been replaced by 5′-CGC-3′ while in snR5mutH, the 5′-AGACCA-3′ H box has been modified to 5′-GGGCCA-3′. Such alteration of box H was shown to impair accumulation of the snR5 snoRNA in yeast (Bortolin et al. 1999). As shown in Figure 3, modifications of either box ACA (panel B) or box H (panel C) have little effect on Cbf5Δp–snoRNA complex formation at elevated Cbf5Δp concentration (500 nM) (as compared to the wild-type RNA, panel A). However, band quantifications revealed that each modification reduced the level of the complex at lower protein concentrations. These results show that neither box H nor box ACA are strictly required for assembly of snR5–Cbf5Δp complexes. However, each box increases the affinity of Cbf5Δp for the H/ACA snoRNA.

FIGURE 3.

Function of conserved H and ACA boxes in Cbf5Δp–snR5 complex assembly. EMSAs were performed with 0.125 nM of labeled transcripts of wild-type snR5 (A), or modified snR5, snR5mutACA (B), in which the 5′-ACA-3′ box has been modified to 5′-CGC-3′, snR5mutH (C), in which the 5′-AGACCA-3′ H box has been replaced by 5′-GGGCCA-3′, and snR5mutH/ACA (D), in which both H and ACA boxes are modified. Increasing amounts of purified Cbf5Δp (25–500 nM, lanes 2–5) were added to binding reactions, except for those loaded in lanes 1 (A–D), which lacked protein. Binding reaction loaded in lane 6 (D) was performed with 1000 nM of protein. Complexes were resolved by electrophoresis on native 6% polyacrylamide gels. (E) Competition experiments were performed with 0.1 nM of labeled snR5 and a protein concentration of 500 nM. Competitor RNAs were added to binding reactions in 100×, 500×, 1000×, or 5000× molar excess. Free snR5 and Cbf5Δp–snR5 complexes were quantified using a phosphorimager (Materials and Methods). The legend is indicated directly on the graph.

Yeast box H/ACA snoRNAs are bipartite RNAs, composed of 5′ and 3′ pseudouridylation pockets, associated with box H and box ACA, respectively (Fig. 2A). When a single box is altered, we cannot exclude the possibility that the second box anchors Cbf5Δp to the modified RNA. We therefore performed EMSAs with a snoRNA featuring altered H and ACA boxes, snR5mutH/ACA (Fig. 3D). Affinity of Cbf5Δp for snR5mutH/ACA was found to be substantially decreased relative to its affinity for the wild-type RNA. Even at the highest Cbf5Δp concentration (1000 nM; Fig. 3D, lane 6), a substantial amount of free snR5mutH/ACA remained. Intriguingly, two very faint Cbf5Δp–snR5mutH/ACA complexes could be observed at high protein concentrations. The faint appearance of a second complex of lower electrophoretic mobility could also be observed with snR5mutH and in some cases at high protein concentration with wild-type snR5. We have not investigated the nature of this complex further, but its lower electrophoretic mobility could indicate a higher stoichiometry of the protein within this complex.

To assess the specificity of complexes assembled with the modified snR5 RNAs, competition experiments were performed. EMSAs were performed in the presence of a fixed amount of wild-type radiolabeled snR5 and increasing amounts of either cold wild-type or modified snR5 RNAs as competitors. Quantification of the Cbf5Δp–snR5 complexes as a function of competitor RNA amounts is shown in Figure 3E. Results, expressed in percentages, were normalized with the intensity of the complex obtained in the absence of competitor, for each experiment. Whatever the nature of the snR5 competitor RNA (wild type or modified), the quantity of complex decreased when the amount of competitor increased. This was not observed with the U24 C/D snoRNA. However, the competitor effect is reduced with snR5mutACA or snR5mutH and even more so with snR5mutH/ACA. Indeed, whereas a 1000-fold excess of wild-type snR5 reduces the relative quantity of the Cbf5Δp–snR5 complex to ∼20% of the quantity without competitor, 50% of complex is still detected with the same quantity of snR5mutH or snR5mutACA. The quantity of complex increases to 70% with the same excess of snR5mutH/ACA. The effects of modifying the H or ACA box are identical, which could indicate that both boxes, despite different sequences, have the same function in Cbf5Δp binding. Furthermore, the additive effects of alterations in box H and box ACA suggest rescue by the wild-type box when the other is altered.

Together, these results show that both box H and box ACA, even though not absolutely required for Cbf5Δp–snR5 complex assembly, increase the affinity of the protein for snR5. This suggests that the protein interacts with these conserved motifs at least transiently during complex assembly. Furthermore, competition experiments with snR5mutH/ACA suggest that the protein recognizes additional features of snR5.

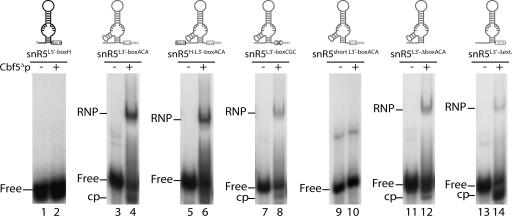

Cbf5Δp binds an RNA consisting of the snR5 3′ stem–loop and the flanking single-stranded hinge region

In a next set of experiments, we searched for the minimal features of snR5 required for the interaction with Cbf5Δp. We first asked whether Cbf5Δp can assemble a stable complex with single stem–loop snR5 derivatives (Fig. 4). We tested snR5 derivatives that retained the 5′ stem–loop and the H box (snR5L5′-boxH, snR5 bases G1 to U98), or the remaining part of the single-stranded hinge region, the 3′ stem–loop and the ACA box (snR5L3′-boxACA, snR5 bases 96–200). Radiolabeled snR5L5′-boxH and snR5L3′-boxACA were incubated with Cbf5Δp at 500 nM final concentration. As shown in Figure 4, the protein does not bind to snR5L5′-boxH (lane 2) but forms a stable complex with snR5L3′-boxACA (lane 4). However, snR5L3′-boxACA is less efficiently bound than wild-type snR5. As described in the previous section, both H and ACA boxes increase the affinity of Cbf5Δp for snR5 (Fig. 3). We therefore tested whether adding the H box to substrate snR5L3′-boxACA, generating snR5H-L3′-boxACA, could increase the affinity of Cbf5Δp for this single stem–loop snoRNA. This was not the case (Fig. 4, lane 6), this latter substrate being slightly less efficiently bound than snR5L3′-boxACA, perhaps because of a folding defect. We then asked whether binding of Cbf5Δp to snR5L3′-boxACA requires an intact ACA box. As shown in Figure 4, lane 8, Cbf5Δp can interact with substrate snR5L3′-boxCGC featuring an altered ACA box, although its affinity for this RNA is slightly decreased relative to that for snR5L3′-boxACA: In a typical experiment, ∼70% of snR5L3′-boxACA is shifted, while only ∼45% of snR5L3′-boxCGC is shifted at the same protein concentration. This suggests that box ACA increases the affinity Cbf5Δp for the single stem–loop substrate snR5L3′-boxACA as observed in the full-length snR5 context. The presence of a single-stranded hinge domain between the two stem–loop structures is an important feature of eukaryotic box H/ACA snoRNAs. To assess the role of this hinge domain in the binding of Cbf5Δp to snR5L3′-boxACA, we have tested a shortened snR5L3′-boxACA derivative in which the 5′ single-stranded region was removed. This substrate (snR5short L3′-boxACA) is hardly bound at all by Cbf5Δp (Fig. 4, lane 10). This suggests an important function for the hinge domain in the formation of the RNA–protein complex. To confirm this point, and exclude folding defects of snR5short L3′-boxACA, we have performed the same experiment with Pab91, an archaeal ACA sRNA (Charpentier et al. 2005). This natural single stem–loop ACA sRNA was shown to be an efficient binding substrate for the purified archaeal aCbf5. However, we were not able to detect any complex formation when this RNA was tested by EMSA with Cbf5Δp (data not shown). We also tested the importance of the presence of a single-stranded region 3′ to the stem for Cbf5Δp binding. Contrary to the removal of the 5′ single-stranded hinge region, removal of the 3′ single-stranded tail (generating snR5L3′-ΔboxACA) does not abolish binding of Cbf5Δp (Fig. 4, lane 12). Finally, we assessed the contribution of the atypical short stem–loop inserted in the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket, one clear distinguishing feature between 5′ and 3′ halves of snR5. Removal of this extension (generating snR5L3′-Δext.) reduces Cbf5Δp binding affinity (Fig. 4, lane 14) in comparison to that for snR5L3′-boxACA. Intriguingly, we noticed that addition of Cbf5Δp to the snR5L3′-Δext. substrate resulted in increased migration of the majority of the unbound RNA. We realized that this phenomenon could in fact be detected with other RNA substrates but to a lesser extent (see bands labeled “cp” in Fig. 4). This increased migration is due to a cleavage event, as revealed by purification of the labeled RNAs after interaction with Cbf5Δp and their electrophoresis under denaturing conditions (data not shown). We surmise that Cbf5p may remove a uridine base within the pseudouridylation pocket that somehow results in cleavage of the RNA backbone.

FIGURE 4.

Binding of Cbf5Δp to single stem–loop snR5 derivatives. EMSAs were performed with 0.125 nM of 32P-labeled transcripts of various single stem–loop snR5 derivatives pictured above each gel. (Lanes 1,2) Derivative snR5L5′-boxH (snR5 bases G1 to U98), encompassing the 5′ stem–loop plus the H box. (Lanes 3,4) Derivative snR5L3′-boxACA (snR5 bases 96–200), encompassing the single-stranded hinge domain, the 3′ stem–loop, plus the ACA box. (Lanes 5,6) Derivative snR5H-L3′-boxACA (snR5 bases 90–200), similar to the snR5L3′-boxACA substrate but including the H box. (Lanes 7,8) snR5L3′-boxCGC derivative, identical to snR5L3′-boxACA except that the ACA box has been converted to CGC. (Lanes 9,10) snR5short L3′-boxACA (snR5 bases 108–200), similar to the snR5L3′-boxACA substrate but lacking the single-stranded hinge region. (Lanes 11,12) snR5L3′-ΔboxACA (snR5 bases 96–192), similar to the snR5L3′-boxACA substrate but lacking the 3′ single-stranded tail. (Lanes 13,14) snR5L3′-Δext. (snR5 bases 96–115 and 128–200), similar to the snR5L3′-boxACA substrate but lacking the atypical stem–loop insertion within the pseudouridylation pocket. (cp) cleaved unbound RNA probe.

Altogether, these results show that the minimal Cbf5Δp binding substrate derived from snR5 encompasses a single-stranded hinge domain and the 3′ stem–loop. Furthermore, as observed for the wild-type snR5, the presence of an ACA box stabilizes the interaction with Cbf5Δp.

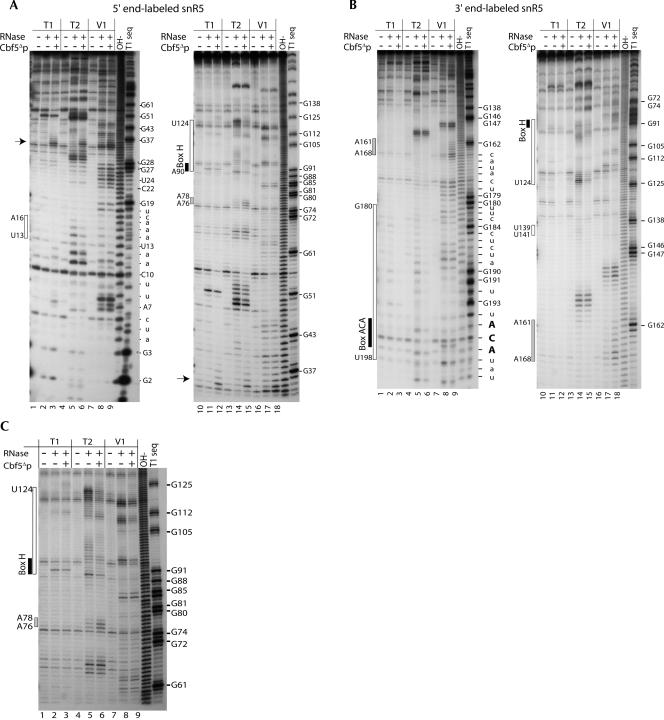

Footprint analysis of the Cbf5Δp–snR5 interactions by RNase probing

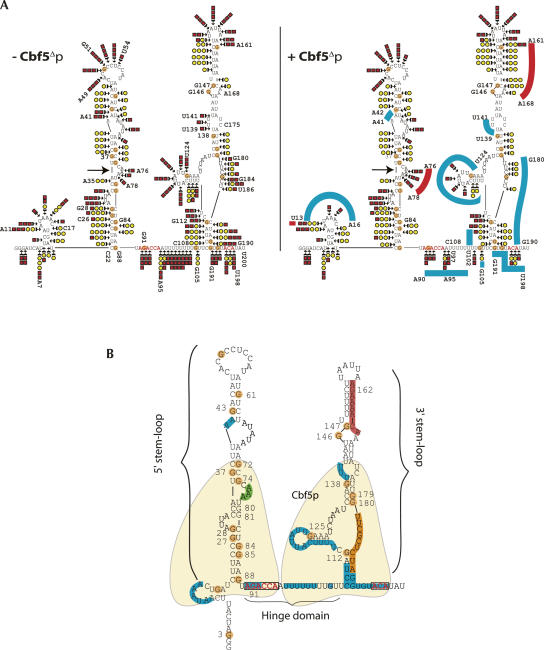

To more precisely investigate the interactions of Cbf5Δp with snR5, we mapped by enzymatic footprinting the binding site(s) of the protein on the RNA. The wild-type snR5 snoRNA was in vitro transcribed and labeled with 32P either at the 3′ or 5′ end (see the Materials and Methods section). RNA–protein complexes were assembled using 500 nM of Cbf5Δp and 5–10 nM of snR5. We verified that under these conditions, ∼80% of the snR5 RNA was trapped in a single RNA–protein complex (data not shown). Mapping was carried out by partial digestion of the RNA with two structure-specific RNases, RNase T2 and RNase V1, which, respectively, cleave unpaired and paired or stacked nucleotides. We have also included a partial RNase T1 digestion to map unpaired G residues. Alkaline hydrolysis and RNase T1 sequencing reaction were included as reference ladders. Cbf5Δp-snR5 complexes were allowed to assemble by incubating the reactants for 10 min at 25°C prior to RNase addition. RNase digestion was ended by phenol/chloroform extraction and concentrated samples analyzed on 15% polyacrylamide–7 M urea sequencing gels. The structure of free snR5 was obtained by RNase treatment of the RNA treated as described above. Autoradiographies of dried sequencing gels are presented in Figure 5A, and B, corresponding, respectively, to experiments performed with the 5′ or 3′ end-labeled snR5. We also show in Figure 5C a higher resolution sequencing gel to focus on positions within the hinge domain and the lower part of the pseudouridylation pocket of the 3′ stem–loop structure. Digestion profiles are plotted on the predicted snR5 structure in Figure 6A either in the absence (left part) or in presence (right part) of Cbf5Δp. Differences in digestion patterns between bound and unbound RNA are highlighted in blue and red, for reduced and enhanced sensitivity to RNase digestion, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

Enzymatic footprinting of Cbf5Δp bound to snR5. Enzymatic footprinting was carried out as described in the Material and Methods section on 5′ (A and C) or 3′ (B) 32P end-labeled snR5, and samples were separated on 15% polyacrylamide sequencing gels. Electrophoresis was carried out for 1 h 30 min (A, B, left gels), 4 h (A, B, right gels), or 7 h (C). RNases used for probing are indicated above each lane. (T1) RNase T1 digestion. (T2) RNase T2 digestion. (V1) RNase V1 digestion. (OH−) alkaline hydrolysis ladder. (T1 seq) RNase T1 digestion ladder obtained in denaturating conditions. Positions of interest are indicated on the right side of each gel. On the left side of gels, protected regions are delimited by open white boxes and positions that display cleavage enhancement are delimited by gray boxes. Conserved H box and ACA box are highlighted by black boxes. The arrow indicates the position of the specific Cbf5Δp-induced cleavage.

FIGURE 6.

Summary of RNase probing data. (A) Schematic representation of enzymatic digestion data obtained by probing free snR5 (left part) and bound snR5 (right part). Positions digested by RNase T2 and RNase V1 are noted by red squares and yellow circles, respectively. Cleavage efficiency is indicated as follows. (1 symbol) weak cleavage; (2 symbols) mild cleavage; (3 symbols) strong cleavage. On the bound snR5 structure (right), regions that display Cbf5Δp-induced protection are highlighted by blue lines and regions that display increased RNase digestion are highlighted by red lines. (B) Model of Cbf5Δp interactions with snR5. Probing results in the presence of Cbf5Δp are indicated on the snR5 structure. (Blue lines) Positions protected against RNase T2 or RNase V1 digestion. (Orange line) Positions protected against RNase T2 digestion only. (Red line) Positions more susceptible to RNase V1 digestion. (Green line) Positions more susceptible to RNase T2 digestion. We propose that two Cbf5Δp molecules (indicated in yellow) are bound to snR5, each monomer interacting with one stem–loop and conserved box.

Digestion pattern over the 5′ stem–loop

The 5′ stem–loop of snR5 appears highly structured, with a distribution of RNase T2 and RNase V1 cleavages in the predicted bulges and stems respectively (Fig. 5A, lanes 2,5,8,11,14,17; Fig. 6A, left part). The apical loop is highly exposed to RNase T2 cleavages from position A49 to U54 (Fig. 5A, lane 14) and very efficiently cleaved by RNase T1 at position G51 (Fig. 5A, lane 11). At the extreme 5′ end of the RNA, the pattern of digestion does not fit the predicted structure perfectly. It is important to note that for these small RNA fragments, the RNA fragments from the alkaline hydrolysis ladder migrate slightly faster than corresponding fragments resulting from RNase V1 cleavages due to, respectively, 5′ P and 5′ OH ends (Fig. 5A, lane 8 and OH− ladder). We observe strong RNase V1 cleavage at position A7 that is supposed to be unpaired (Fig. 5A, lane 8). As predicted, the region between bases A11 and C17, as part of a loop structure, is exposed to RNase T2 cleavages (Fig. 5A, lane 5), but RNase V1 digestion at the same positions (Fig. 5A, lane 8) suggests that either the loop can stack onto another part of snR5 or that the entire region may adopt alternative conformations. Upon addition of the protein, we detect subtle effects on the digestion pattern of the 5′ half of snR5 (Fig. 5A, lanes 3,6,9,12,15,18). We can detect a weak protection against RNase V1 and RNase T2 digestion at positions U13 to A16 within the predicted loop (Fig. 5A, lanes 6,9). Furthermore, at position A12, an enhancement of RNase V1 cleavage is associated with weaker sensitivity to RNase T2 (Fig. 5A, lanes 6,9). In the 5′ stem–loop, Cbf5Δp binding induces notable enhancements of RNase T2 cleavage at positions A76 to A78 that are included in the pseudouridylation pocket (Fig. 5A, lane 15). We also observe a weak protection to RNase T2 cleavages within the apical loop (A49 to U54) associated with reduced RNase T1 sensitivity at G51. However, this highly exposed region is still strongly sensitive to RNase digestion. Furthermore, we note strong Cbf5Δp-induced cleavage at position A35 (Fig. 5A, lanes 12,15,18; arrow) that is also detected in the absence of RNases (data not shown). We do not know the nature of this highly specific cleavage, but, interestingly, position A35, when paired with the rRNA substrate, is exactly adjacent to the target uridine.

Digestion pattern in the single-stranded hinge domain and the 3′ stem–loop

As expected, the hinge domain is highly exposed to RNase T2 digestion (Fig. 5C, lane 5, from U89 to U107) but positions A95 and G105 were cleaved by RNase V1, suggesting stacking of these bases (Fig. 5C, lane 8). A long stretch of 8 U's is present in the hinge domain of snR5. Addition of Cbf5Δp induces strong protection against RNase T2 digestion from residues U97 to U102 within this motif (Fig. 5C, lanes 5,6). Within the H box, we note weak protection at positions A90, G91, and A92 against RNase T2 digestion (Fig. 5C, lanes 5,6). Position A95 of the H box is highly efficiently cleaved by RNase V1 and the Cbf5Δp-induced protection extends to this position (Fig. 5C, lanes 8,9). However, at the same position, we detect weak RNase T2 cleavage that is not affected by the presence of the protein (Fig. 5C, lanes 5,6).

The predicted snR5 structure shows an atypical short stem–loop within the pseudouridylation pocket (Fig. 2A). This structure was confirmed by the RNase digestion profiles (Fig. 5C, lanes 5,8). Addition of Cbf5Δp induces strong protection within this region (residues C108 to U124) over the two contiguous stems and the loop (Fig. 5A, lanes 15,18; Fig. 5C, lanes 6,9). No structural information was obtained for residues G125 to G138, which were not cleaved by RNases. Above the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket, three positions cleaved by RNase T2 (bulge residues U139 to U141) on the free snR5 are protected upon addition of Cbf5Δp (Fig. 5B, lanes 14,15).

Cbf5Δp binding induces important modifications of the RNase digestion profiles within the apical 3′ stem. Addition of the protein leads to strong RNase V1 cleavages from nucleotides A161 to A168 that are poorly digested in the free RNA (Fig. 5B, lanes 17,18). This digestion pattern may reflect structural rearrangements resulting in the exposure of the stem structure upon binding of Cbf5Δp.

Concerning the region from nucleotides C175 to U200 (RNA 3′ end), the digestion pattern is more ambiguous. It is important to note that in the case of 3′ end labeling of the RNA, fragments resulting from RNase V1 cleavage migrate faster than the corresponding fragments on the RNase T1 and alkaline hydrolysis ladder (Fig. 5B, lanes 8, 9, OH− and T1 seq). When considering the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket and the short stem immediately above, we mostly detect strong sensitivity to RNase V1 digestion (Fig. 5B, lane 8). However, positions G184 and C185 are clearly sensitive to RNase T2 digestion, and we observe cleavages at position U186 by both RNases (Fig. 5B, lanes 5,8). In the basal stem, positions of the upper part (from C187 to A189) are mostly paired, as revealed by strong RNase V1 cleavages. However, weaker RNase T2 cleavages at these positions suggest the adoption by this region of an alternative open conformation. Basal positions of the stem and most of the 3′ end of the RNA, including the ACA box, appear mostly single-stranded as shown by strong RNase T2 and RNase T1 cleavages from G190 to A197 (Fig. 5B, lanes 2,5). However, we detect RNase V1 cleavage at position C196 in the ACA box, suggesting that this position is able to stack (Fig. 5B, lane 8). We do not consider that bands observed at positions U194 and A195 in the presence of RNase V1 (Fig. 5B, lane 8) result from specific cleavage. Indeed, these bands do not display the typical shift relative to bands resulting from alkaline hydrolysis.

Upon addition of Cbf5Δp, we do not observe any effect on the RNase V1 digestion pattern (Fig. 5B, lane 9), whereas we observe clear protection against RNase T2 and RNase T1 cleavages within a region encompassing nucleotides G180 to U194 (Fig. 5B, lanes 3,6). Basal positions of the basal stem and positions preceding the ACA box (from G190 to U194) are clearly mostly single-stranded and are protected against RNase T2 digestion when Cbf5Δp is added (Fig. 5B, lanes 5,6). This is also the case for positions A195 and A197 of the ACA box. These results strongly suggest that Cbf5Δp protects the bottom of the stem and the single-stranded 3′ region, including the ACA box.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we report the first in vitro study of the interactions with a H/ACA snoRNA of the purified recombinant N-terminal domain of a eukaryotic Cbf5 protein. We show that this domain binds a H/ACA snoRNA directly and we report the precise mapping by footprinting analysis of its binding site(s) on the RNA.

Since sufficient quantities of recombinant full-length yeast Cbf5p could not be produced, we have used in our studies the longest truncated derivative of Cbf5p that could be properly expressed and purified. This protein, Cbf5Δp, encompasses the first 345 and lacks the last 138 amino acids of the full-length protein. Cbf5Δp retains the two highly conserved TruB and PUA domains. Thus, this protein is highly homologous to archaeal aCbf5 that was shown to assemble in vitro into an active particle with aNop10, aGar1, and L7Ae (Baker et al. 2005). The biological function of the eukaryotic C-terminal extension absent in Cbf5Δp is not clear. In the case of yeast Cbf5p, 10 tandemly repeated KKE and KKD sequences are located near the C terminus of the protein. Complementation experiments with a truncated Kluyveromyces lactis Cbf5p lacking these terminal repeats have shown that they are not required for viability (Winkler et al. 1998). This is consistent with the proposal that these repeats constitute an interaction domain for the nonessential methyltransferase Tgs1p, which catalyzes synthesis of the trimethyl cap of nonintronic snoRNAs (Mouaikel et al. 2002). Interestingly, in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans, a transposon insertion in the SWOC1 gene encoding the ortholog of Cbf5p is viable, although it leads to the production of a protein lacking most of the C-terminal domain (Lin and Momany 2003). The deletion encompasses a region that was implicated in the case of human dyskerin in the nuclear/nucleolar localization of the protein (Heiss et al. 1999; Youssoufian et al. 1999), but the identified nuclear localization motif is not well conserved in the yeast orthologs.

Our results demonstrate that yeast Cbf5Δp retains the domain(s) required for protein assembly in a specific complex with a H/ACA snoRNA. Indeed, we show that the protein binds a box H/ACA snoRNA but not the U24 box C/D snoRNA. By band retardation assays, we have studied the RNA determinants required for yeast Cbf5Δp binding. We have first investigated the role of the conserved H and ACA boxes. We show that each box increases the affinity of Cbf5Δp for the snoRNA but only to a mild extent. Altering both conserved boxes renders the RNA a poor binding substrate for Cbf5Δp. Nevertheless, alteration of both boxes does not completely abolish protein binding, as clearly revealed by competition experiments. These results suggest that Cbf5Δp recognizes both the conserved boxes and structural elements of H/ACA RNAs. The same conclusions can be drawn from footprinting data (for a compilation of footprinting results, see Fig. 6B). The single-stranded 3′ end of the full-length snR5 molecule, including the ACA box, is clearly protected against RNase T2 cleavage upon Cbf5Δp binding. This protection extends to two consecutive G residues at the base of the 3′ stem, which appear mostly unpaired as revealed by strong RNase T2 cleavage of the unbound RNA. We also observe weak protection of the H box due to Cbf5Δp binding. In addition, strong protection was obtained over the rest of the single-stranded hinge domain and over the small loop upstream of the 5′ stem–loop. We envisage that the 5′ region preceding the 5′ stem–loop, the hinge domain, and the 3′ end of the RNA constitute a binding platform for Cbf5p. This platform includes the conserved boxes. We also observe protection against RNase T2 cleavage in the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket. However, this region is mostly paired or stacked, as revealed by RNase V1 digestion of the free RNA, and this digestion pattern is not affected by binding of Cbf5Δp. Interestingly, pairing was also detected by NMR within the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket of naked human U65 snoRNA in solution (Khanna et al. 2006). This protection could thus reflect complete protein-induced stacking or pairing within the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket. Nevertheless, we also observe specific Cbf5Δp-induced cleavage in the 5′ pseudouridylation pocket. This observation strongly suggests that the protein interacts at least transiently with this region of the snoRNA. Fixation of Cbf5Δp on the “basal platform” and/or the pseudouridylation pocket seems to have important consequences on the apical stem–loop of the 3′ half of snR5. We note three positions protected from RNase T2 cleavage in a loop above the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket. We do not know whether this results from direct interactions with the protein or from conformational changes induced by protein binding. Indeed, we can clearly detect conformational changes in the 3′ apical stem–loop, with strong protein-induced exposition of the stem to RNase V1 cleavage. Protein-induced cleavage modifications in the 5′ stem–loop are weaker, but, as for the 3′ half, we note protections in a bulge (over residues A41 and A42), associated this time with weaker reactivity in the apical loop. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that Cbf5p contacts the apical loop of the 5′ stem, a possibility also proposed for archaeal Cbf5, which shows reduced affinity for a H/ACA sRNA, the apical loop of which has been altered (Baker et al. 2005). Interestingly, Cbf5Δp binding results in enhancement of RNase T2 cleavage at three positions within the 5′ pseudouridylation pocket (A76 to A78). However, this may result from Cbf5Δp-induced cleavage at position A35 that probably leads to exposure of these bases to RNase cleavage.

The double stem structure of eukaryotic H/ACA snoRNAs is not an absolute requirement for yeast Cbf5Δp binding. We show that purified yeast Cbf5Δp also binds an RNA molecule containing the 3′ stem–loop, the ACA box, and part of the central single-stranded hinge of snR5. The affinity of the protein for this substrate is reduced when compared to wild-type snR5, but equivalent to the affinity of Pyrococcus abyssi aCbf5 for the single stem–loop sRNA Pab91 (Charpentier et al. 2005). However, yeast Cbf5Δp was unable to interact with the short 3′ stem–loop-box ACA substrate lacking the 5′ extension from the hinge region. This is entirely consistent with the finding that this part of the hinge region of snR5 is strongly protected from RNase T2 cleavage upon yeast Cbf5Δp binding. Surprisingly, Cbf5Δp failed to bind to the 5′ stem–loop-H box substrate. We do not think that this is due to intrinsic differences between box ACA and box H since modifications of either box have exactly the same effect on complex assembly in the context of the full-length RNA. In silico RNA folding analyses rather suggest that in the single stem–loop context, the 5′ end pairs with the H box, thus maybe inhibiting interactions with Cbf5Δp. Moreover, even in the context of full-length snR5, the 3′ half of the molecule may constitute a better Cbf5p binding substrate than the 5′ half, as suggested by the far more extensive protections observed over the former compared to the latter. The different behaviors of the two halves of the molecule may in part be due to the presence of an atypical short stem–loop inserted in the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket. Strikingly, we detect strong Cbf5Δp-induced protection within this additional motif. It could result from nonspecific interactions with the protein or changes in the RNA conformation that mask this region. However, by homology with the cocrystal structure of the bacterial pseudouridine synthase TruB (Hoang and Ferré-D'Amaré 2001) with its RNA substrate, it has been proposed that the catalytic domain of Cbf5p recognizes a double-stranded structure, formed by pairing of the guide snoRNA with the target RNA (Rashid et al. 2006). It is possible that in the absence of target RNA, the atypical stem–loop inserted in the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket of snR5 interacts with the catalytic domain of Cbf5p in a similar manner. Such interactions could explain the more extended protection observed in the 3′ stem–loop by stabilization of the protein–RNA interactions. Nevertheless, the presence of the atypical stem–loop is clearly not an absolute requirement for Cbf5Δp binding to snR5 3′ half, since its removal reduced binding but did not abolish it.

Altogether, our results are most consistent with a model where a dimer (or an even number of molecules) of Cbf5p interacts with snR5, each monomer interacting with the 5′ stem–loop-box H or the 3′ stem–loop-box ACA part of the RNA, at the level of the lower stems and flanking sequences and probably also the pseudouridylation pockets. In the case of snR5, at least, the binding site of highest affinity is constituted by the 3′ half of the molecule, as suggested by the lack of extensive footprint over the 5′ stem–loop of snR5 upon Cbf5Δp binding. We have obtained complementary results that support the multimer hypothesis. We have tested by EMSA a 5′ deleted version of snR5 (snR5Δ17) in which the first 17 nt were removed, keeping intact the first stem–loop. In an RNA titration experiment, we observed at low protein concentration a fast migrating complex that is converted at higher concentrations into a second complex of lower electrophoretic mobility, similar to the mobility of the wild-type snR5/Cbf5Δp complex (data not shown). Interestingly, Baker et al. (2005) also observed two complexes when they tested binding of the archaeal aCbf5 protein on bipartite eukaryotic or archaeal H/ACA RNAs. They also proposed that these complexes reflect association of a monomer and a dimer of aCbf5 with the RNA. Our data are also in perfect agreement with a model of archaeal aCbf5/RNA interactions recently put forward by Rashid et al. (2006). They proposed that aCbf5 interacts via the TruB catalytic domain with the pseudouridylation pocket and via the PUA domain with the lower part of the stem and the conserved ACA box. This model has received support from recent biochemical data (Manival et al. 2006). These authors have shown that the intrinsic pseudouridylase activity of the N-terminal catalytic domain of aCbf5 is highly stimulated by addition in trans of the PUA domain but that this stimulation is dependent on the ACA box.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of recombinant protein Cbf5Δp

The DNA sequence encoding the truncated Cbf5p protein, Cbf51–345, was obtained by PCR amplification from yeast genomic DNA using oligonucleotides CBF5-NcoI 5′ (RC9) (5′-TTGCTTTAGGAGGAAACTTCGGTACC-3′) and CBF5ΔKKE -His6-NotI 3′ (RC11) (5′-ACATAGTACCTTTCTCTAAATGTGGTAGTGGTAGTGGTAATTCGCCGGCG-3′). The resulting PCR fragment was cloned in the pACYC Duet1 vector (Novagen) cut by NcoI and NotI, creating pACYCDuet-Cbf5Δp-6His. The pACYCDuet-Cbf5Δp-6His plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 (λDE3) (Novagen) to produce the His-tagged Cbf5Δp protein. Transformed bacteria were grown at 37°C in 2× YT medium (16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) supplemented with 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol to an A600 of 0.6. Recombinant protein expression was then induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and culturing was continued for 4 h at the same temperature. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (6000g, 20 min, 4°C), resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and stored at −80°C.

The Cbf5Δp protein is expressed in E. coli as insoluble aggregates. Thus, the protein was purified from inclusion bodies under denaturing conditions and refolded essentially as described by Tresaugues et al. (2004). Briefly, bacteria were thawed and sonicated on ice. Inclusion bodies were collected by centrifugation at 13,000g for 30 min at 4°C and washed with a 0.5% Triton X-100 solution containing 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol for 1 h at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the pellet was solubilized in denaturing buffer (buffer A supplemented with 6 M guanidium chloride) by stirring for 2 h at room temperature. After centrifugation, the supernatant was added to Ni-Sepharose resin (Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow; Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with denaturing buffer and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Protein was renatured by step gradient washing of the Ni-Sepharose resin charged with Cbf5Δp protein in buffer A containing successively 4 M, 2 M, and 1 M Gu-HCl and no Gu-HCl. The resin was then diluted 15-fold to maintain low protein concentration in refolding buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM imidazole at pH 8, 10% glycerol, 0.2% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 2 μg/mL pepstatin, 1 μg/mL leupeptin) and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing with refolding buffer, Cbf5Δp protein was eluted from the column with 300 mM imidazol. Cbf5Δp-containing fractions were identified by SDS-PAGE and gel staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. Positive fractions were pooled and Cbf5Δp was loaded on a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with GF buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.2% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2). Cbf5Δp-containing fractions were tested for their ability to induce a shift of the snR5 H/ACA snoRNA by electrophoresis mobility shift assays. Positive fractions were pooled and the protein was concentrated to ∼0.1 mg/mL using an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter (Millipore). Finally, glycerol was added to the protein solution to a final concentration of 40%.

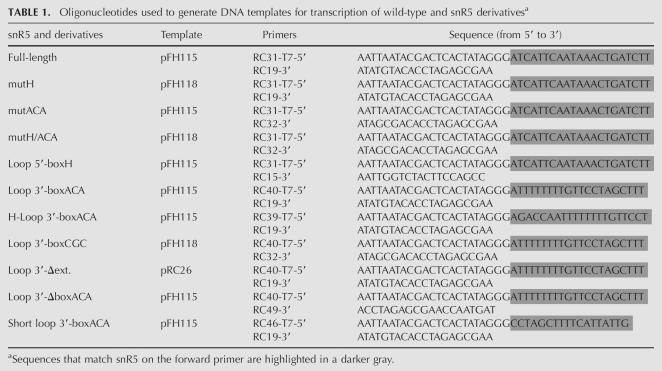

In vitro transcription of RNAs

DNA templates used for in vitro transcription of wild-type or modified versions of snR5 snoRNA were generated by PCR using plasmids pFH115, pFH118, or pRC26 containing the wild-type snR5 sequence or a modified snR5 sequence mutated at the level of the H and ACA boxes, or lacking the atypical stem–loop insertion in the 3′ pseudouridylation pocket, respectively. All oligonucleotides used in this study to generate transcription templates are listed in Table 1. The forward primer always contained the T7 RNA polymerase promoter as 5′ extension.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used to generate DNA templates for transcription of wild-type and snR5 derivativesa

Plasmids pFH115 and pFH118 were constructed as follows. The full-length snR5 sequence was PCR-amplified using yeast genomic DNA and oligonucleotides snR5-5′-EcoRI (5′-CCCCCGAATTCATCATTCAATAAACTGATCTTCCGG-3′) and snR5-3′-HindIII (5′-CCCCCAAGCTTCACGTGATATGTACACCTAGAGCGAACCAATG-3′). The resulting PCR fragment was digested by EcoRI and HindIII and inserted into the pGEM1 vector (Promega) cut by the same enzymes, producing plasmid pFH115. The modified snR5 sequence containing mutated H and ACA boxes was amplified in two steps. The downstream half of the sequence was amplified using mutagenic primers snR5-mutH (5′-GCGCAAATGGCTGGAAGTGGGCCAATTTTTTTTGTTCCTAGCTTTTC-3′) and snR5-ACAmut-3′-HindIII (5′-CCCCCAAGCTTCACGTGATAGCGACACCTAGAGCGAACCAATGATAATTTG-3′). The resulting fragment was then 5′ extended in a second round of PCR using the snR5-5′-EcoRI primer. The second round PCR fragment was digested by EcoRI and HindIII and inserted into the pGEM1 vector (Promega) cut by the same enzymes, producing plasmid pFH118. Plasmid pRC26 was constructed by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis of double-stranded DNA as described by Weiner et al. (1994) using pFH115 and primers snR5-Loop3′Δext.-5′ (5′-ATCTAATCCAG-TTTTAATGG-3′) and snR5-Loop3′Δext.-3′ (5′-AAGCTAGGAACAAAAAAAAT-3′).

In vitro transcription of RNAs was performed with T7 or T3 RNA polymerase (Promega) following standard procedures. Full-length snR5 and derivatives were in vitro transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase using DNA fragments amplified by PCR. The yeast box C/D U24 snoRNA was in vitro transcribed from plasmid pyU24 (Henras et al. 2001) cut by HindIII using T3 RNA polymerase. Uniformly 32P-labeled in vitro transcribed snoRNAs were synthesized in the presence of [α32P]CTP. The full-length snR5 RNA used in footprinting experiments was transcribed following the large-scale RNA synthesis protocol (Promega) using 1 μg of PCR fragment as template. The reaction was incubated overnight at 37°C. The RNA was then subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitated with ethanol. The full-length transcript was purified on a 8% polyacrylamide (19:1)-7 M urea gel. 5′ end labeling with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Biolabs) was performed on the dephosphorylated RNA in the presence of [γ32P]ATP and 3′ end labeling was carried out with [5′-32P]pCp and T4 RNA ligase (Biolabs). End-labeled RNAs were subsequently purified on 8% polyacrylamide (19:1)-7 M urea gels.

Electrophoresis mobility shift assays

Uniformly 32P-labeled in vitro transcribed snoRNAs were heat-denatured in water at 70°C for 10 min and placed 10 min on ice. RNAs were then diluted in a 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2 ice-cold buffer to obtain an RNA concentration of ∼0.5 fmol/μL, and were left at room temperature for 1 h. About 2.5 fmol of 32P-labeled RNAs were mixed with the required amounts of purified Cbf5Δp in a final 20 μL binding buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 100 ng/μL E. coli tRNA (Roche), 100 ng/μL BSA. In competition experiments, unlabeled competitor RNAs, previously heat-denatured and cooled in the same way, were added to the labeled RNAs. The binding reactions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and subjected to native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in gels containing 6% polyacrylamide, 50 mM Trizma base, 50 mM glycine, 2 mM MgCl2. Glycerol at 5% final concentration was added to the gels used for the analysis of single stem derivatives of snR5 (Fig. 4). Electrophoresis was carried out at 20 mA in a 50 mM Trizma base, 50 mM glycine, 2 mM MgCl2 running buffer at 4°C. Quantification of radioactivity in bands corresponding to free or shifted RNAs was carried out with the Image Gauge software (Fuji Film) from PhosphorImager scans (FLA3000IR PhosphorImager; Fuji).

Footprinting assays

Prior to RNase treatment, 3′ or 5′ end-labeled snR5 was renaturated and incubated as for EMSA experiments, with a Cbf5Δp concentration of 500 nM, except that the snR5 concentration was increased to 5–10 nM and the binding reaction volume to 60 μL. The Cbf5Δp-snR5 complex was allowed to form for 10 min at 25°C prior to addition of the RNase. Three nucleases were used: RNase T2 (Sigma), RNase T1 (Roche), and RNase V1 (Ambion). RNases were diluted in 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2 buffer to the following concentrations: RNase T1 (0.1 U/μL), RNase T2 (1 U/μL), RNase V1 (0.03 U/μL). Six microliters of RNase were added in the binding reaction and incubation was extended for 5 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Enzymatic probing of naked snR5 was performed in parallel in the same conditions. Samples were resuspended in 10 μL of acrylamide gel loading buffer (95% formamide, 18 mM EDTA, 0.025% SDS, 0.025% xylene cyanol, 0.025% bromophenol blue). RNase T1 and alkaline ladder were generated as previously described (Bortolin et al. 2003). Samples were subjected to electrophoresis on 15% polyacrylamide denaturating gels.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. van Tilbeurgh for support, N. Leulliot for advice, B. Clouet d'Orval and A. Henras for advice and critical reading of the manuscript, and B. Charpentier for reagents. We are thankful to members of the Ferrer Laboratory for help and numerous discussions and D. Villa for art work. C.N. is a recipient of a post-doctoral fellowship from the CNRS. This work was supported by the CNRS, the Université Paul Sabatier, and grants from l'Agence Nationale de la Recherche and from La Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (“Equipe Labellisée”).

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.141206.

REFERENCES

- Atzorn, V., Fragapane, P., Kiss, T. U17/snR30 is a ubiquitous snoRNA with two conserved sequence motifs essential for 18S rRNA production. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1769–1778. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1769-1778.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.L., Youssef, O.A., Chastkofsky, M.I., Dy, D.A., Terns, R.M., Terns, M.P. RNA-guided RNA modification: Functional organization of the archaeal H/ACA RNP. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:1238–1248. doi: 10.1101/gad.1309605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakin, A.G., Smith, L., Fournier, M.J. The RNA world of the nucleolus: Two major families of small RNAs defined by different box elements with related functions. Cell. 1996;86:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolin, M.L., Ganot, P., Kiss, T. Elements essential for accumulation and function of small nucleolar RNAs directing site-specific pseudouridylation of ribosomal RNAs. EMBO J. 1999;18:457–469. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolin, M.L., Bachellerie, J.P., Clouet-d'Orval, B. In vitro RNP assembly and methylation guide activity of an unusual box C/D RNA, cis-acting archaeal pre-tRNA(Trp) Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6524–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Antonelli, C., Henry, Y., Gélugne, J.P., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Kiss, T. A small nucleolar RNP protein is required for pseudouridylation of eukaryotic ribosomal RNAs. EMBO J. 1997;16:4770–4776. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charette, M., Gray, M.W. Pseudouridine in RNA: What, where, how, and why. IUBMB Life. 2000;49:341–351. doi: 10.1080/152165400410182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier, B., Muller, S., Branlant, C. Reconstitution of archaeal H/ACA small ribonucleoprotein complexes active in pseudouridylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3133–3144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.L., Greider, C.W. Telomerase RNA structure and function: Implications for dyskeratosis congenita. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.L., Blasco, M.A., Greider, C.W. Secondary structure of vertebrate telomerase RNA. Cell. 2000;100:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80687-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpet, F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzacq, X., Jády, B.E., Verheggen, C., Kiss, A.M., Bertrand, E., Kiss, T. Cajal body-specific small nuclear RNAs: A novel class of 2′-O-methylation and pseudouridylation guide RNAs. EMBO J. 2002;21:2746–2756. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dez, C., Henras, A., Faucon, B., Lafontaine, D., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Henry, Y. Stable expression in yeast of the mature form of human telomerase RNA depends on its association with the box H/ACA small nucleolar RNP proteins Cbf5p, Nhp2p and Nop10p. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:598–603. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.3.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donmez, G., Hartmuth, K., Lührmann, R. Modified nucleotides at the 5′ end of human U2 snRNA are required for spliceosomal E-complex formation. RNA. 2004;10:1925–1933. doi: 10.1261/rna.7186504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragon, F., Pogacic, V., Filipowicz, W. In vitro assembly of human H/ACA small nucleolar RNPs reveals unique features of U17 and telomerase RNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:3037–3048. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3037-3048.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré-D'Amaré, A.R. RNA-modifying enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganot, P., Bortolin, M.L., Kiss, T. Site-specific pseudouridine formation in preribosomal RNA is guided by small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1997a;89:799–809. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganot, P., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Kiss, T. The family of box ACA small nucleolar RNAs is defined by an evolutionarily conserved secondary structure and ubiquitous sequence elements essential for RNA accumulation. Genes & Dev. 1997b;11:941–956. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard, J.P., Lehtonen, H., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Amalric, F., Tollervey, D., Lapeyre, B. GAR1 is an essential small nucleolar RNP protein required for pre-rRNA processing in yeast. EMBO J. 1992;11:673–682. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouet, P., Robert, X., Courcelle, E. ESPript/ENDscript: Extracting and rendering sequence and 3D information from atomic structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3320–3323. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamma, T., Reichow, S.L., Varani, G., Ferré-D'Amaré, A.R. The Cbf5-Nop10 complex is a molecular bracket that organizes box H/ACA RNPs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:1101–1107. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss, N.S., Girod, A., Salowsky, R., Wiemann, S., Pepperkok, R., Poustka, A. Dyskerin localizes to the nucleolus and its mislocalization is unlikely to play a role in the pathogenesis of dyskeratosis congenita. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:2515–2524. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henras, A., Henry, Y., Bousquet-Antonelli, C., Noaillac-Depeyre, J., Gélugne, J.P., Caizergues-Ferrer, M. Nhp2p and Nop10p are essential for the function of H/ACA snoRNPs. EMBO J. 1998;17:7078–7090. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.7078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henras, A., Dez, C., Noaillac-Depeyre, J., Henry, Y., Caizergues-Ferrer, M. Accumulation of H/ACA snoRNPs depends on the integrity of the conserved central domain of the RNA-binding protein Nhp2p. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2733–2746. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henras, A., Dez, C., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Henry, Y. Dyskeratosis congenita: Who is guilty? Med. Sci. (Paris) 2003;19:792–794. doi: 10.1051/medsci/20031989792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henras, A.K., Capeyrou, R., Henry, Y., Caizergues-Ferrer, M. Cbf5p, the putative pseudouridine synthase of H/ACA-type snoRNPs, can form a complex with Gar1p and Nop10p in absence of Nhp2p and box H/ACA snoRNAs. RNA. 2004a;10:1704–1712. doi: 10.1261/rna.7770604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henras, A.K., Dez, C., Henry, Y. RNA structure and function in C/D and H/ACA s(no)RNPs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004b;14:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, C., Ferré-D'Amaré, A.R. Cocrystal structure of a tRNA Psi55 pseudouridine synthase: Nucleotide flipping by an RNA-modifying enzyme. Cell. 2001;107:929–939. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00618-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, M., Wu, H., Johansson, C., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Feigon, J. Structural study of the H/ACA snoRNP components Nop10p and the 3′ hairpin of U65 snoRNA. RNA. 2006;12:40–52. doi: 10.1261/rna.2221606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, T.H., Liu, B., McCully, R.R., Fournier, M.J. Ribosome structure and activity are altered in cells lacking snoRNPs that form pseudouridines in the peptidyl transferase center. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin, E.V. Pseudouridine synthases: Four families of enzymes containing a putative uridine-binding motif also conserved in dUTPases and dCTP deaminases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2411–2415. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine, D.L., Bousquet-Antonelli, C., Henry, Y., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Tollervey, D. The box H + ACA snoRNAs carry Cbf5p, the putative rRNA pseudouridine synthase. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:527–537. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X., Momany, M. The Aspergillus nidulans swoC1 mutant shows defects in growth and development. Genetics. 2003;165:543–554. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.2.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manival, X., Charron, C., Fourmann, J.B., Godard, F., Charpentier, B., Branlant, C. Crystal structure determination and site-directed mutagenesis of the Pyrococcus abyssi aCBF5-aNOP10 complex reveal crucial roles of the C-terminal domains of both proteins in H/ACA sRNP activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:826–839. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, U.T. The many facets of H/ACA ribonucleoproteins. Chromosoma. 2005;114:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0333-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, U.T., Blobel, G. NAP57, a mammalian nucleolar protein with a putative homolog in yeast and bacteria. J. Cell Biol. 1994;127:1505–1514. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.R., Cheng, J., Collins, K. A box H/ACA small nucleolar RNA-like domain at the human telomerase RNA 3′ end. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999a;19:567–576. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.R., Wood, E., Collins, K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 1999b;402:551–555. doi: 10.1038/990141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, J.P., Tollervey, D. Yeast snR30 is a small nucleolar RNA required for 18S rRNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:2469–2477. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouaikel, J., Verheggen, C., Bertrand, E., Tazi, J., Bordonné, R. Hypermethylation of the cap structure of both yeast snRNAs and snoRNAs requires a conserved methyltransferase that is localized to the nucleolus. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:891–901. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni, J., Tien, A.L., Fournier, M.J. Small nucleolar RNAs direct site-specific synthesis of pseudouridine in ribosomal RNA. Cell. 1997;89:565–573. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofengand, J., Malhotra, A., Remme, J., Gutgsell, N.S., Del Campo, M., Jean-Charles, S., Peil, L., Kaya, Y. Pseudouridines and pseudouridine synthases of the ribosome. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2001;66:147–159. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R., Simmons, T., Shuster, E.O., Siliciano, P.G., Guthrie, C. Genetic analysis of small nuclear RNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Viable sextuple mutant. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988;8:3150–3159. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B., Billin, A.N., Cadwell, C., Buchholz, R., Erickson, C., Merriam, J.R., Carbon, J., Poole, S.J. The Nop60B gene of Drosophila encodes an essential nucleolar protein that functions in yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1998;260:20–29. doi: 10.1007/s004380050866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogacic, V., Dragon, F., Filipowicz, W. Human H/ACA small nucleolar RNPs and telomerase share evolutionarily conserved proteins NHP2 and NOP10. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:9028–9040. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9028-9040.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, R., Liang, B., Baker, D.L., Youssef, O.A., He, Y., Phipps, K., Terns, R.M., Terns, M.P., Li, H. Crystal structure of a Cbf5-Nop10-Gar1 complex and implications in RNA-guided pseudouridylation and dyskeratosis congenita. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, P., Darzacq, X., Bertrand, E., Jády, B.E., Verheggen, C., Kiss, T. A common sequence motif determines the Cajal body-specific localization of box H/ACA scaRNAs. EMBO J. 2003;22:4283–4293. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozhdestvensky, T.S., Tang, T.H., Tchirkova, I.V., Brosius, J., Bachellerie, J.P., Hüttenhofer, A. Binding of L7Ae protein to the K-turn of archaeal snoRNAs: A shared RNA binding motif for C/D and H/ACA box snoRNAs in Archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:869–877. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.H., Bachellerie, J.P., Rozhdestvensky, T., Bortolin, M.L., Huber, H., Drungowski, M., Elge, T., Brosius, J., Hüttenhofer, A. Identification of 86 candidates for small non-messenger RNAs from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:7536–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112047299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollervey, D. A yeast small nuclear RNA is required for normal processing of pre-ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1987;6:4169–4175. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresaugues, L., Collinet, B., Minard, P., Henckes, G., Aufrere, R., Blondeau, K., Liger, D., Zhou, C.Z., Janin, J., Van Tilbeurgh, H., et al. Refolding strategies from inclusion bodies in a structural genomics project. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics. 2004;5:195–204. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029017.46332.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Meier, U.T. Architecture and assembly of mammalian H/ACA small nucleolar and telomerase ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 2004;23:1857–1867. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y., Gray, M.W. Evolutionary appearance of genes encoding proteins associated with box H/ACA snoRNAs: cbf5p in Euglena gracilis, an early diverging eukaryote, and candidate Gar1p and Nop10p homologs in archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2342–2352. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, N.J., Gottschalk, A., Neubauer, G., Kastner, B., Fabrizio, P., Mann, M., Lührmann, R. Cbf5p, a potential pseudouridine synthase, and Nhp2p, a putative RNA-binding protein, are present together with Gar1p in all H BOX/ACA-motif snoRNPs and constitute a common bipartite structure. RNA. 1998;4:1549–1568. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, M.P., Costa, G.L., Schoettlin, W., Cline, J., Mathur, E., Bauer, J.C. Site-directed mutagenesis of double-stranded DNA by the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1994;151:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90641-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, A.A., Bobok, A., Zonneveld, B.J., Steensma, H.Y., Hooykaas, P.J. The lysine-rich C-terminal repeats of the centromere-binding factor 5 (Cbf5) of Kluyveromyces lactis are not essential for function. Yeast. 1998;14:37–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980115)14:1<37::AID-YEA198>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Isaac, C., Wang, C., Dragon, F., Pogacic, V., Meier, U.T. Conserved composition of mammalian box H/ACA and box C/D small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein particles and their interaction with the common factor Nopp140. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:567–577. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., McPheeters, D.S., Yu, Y.T. Psi35 in the branch site recognition region of U2 small nuclear RNA is important for pre-mRNA splicing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6655–6662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssoufian, H., Gharibyan, V., Qatanani, M. Analysis of epitope-tagged forms of the dyskeratosis congenital protein (dyskerin): Identification of a nuclear localization signal. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 1999;25:305–309. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1999.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebarjadian, Y., King, T., Fournier, M.J., Clarke, L., Carbon, J. Point mutations in yeast CBF5 can abolish in vivo pseudouridylation of rRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:7461–7472. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker, M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]