Abstract

Background

DNA structure checkpoints are conserved eukaryotic signal transduction pathways that help preserve genomic integrity. Upon detecting checkpoint signals such as stalled replication forks or double-stranded DNA breaks, these pathways coordinate appropriate stress responses. Members of the PI-3 kinase related kinase (PIKK) family are essential elements of DNA structure checkpoints. In fission yeast, the Rad3 PIKK and its regulatory subunit Rad26 coordinate the detection of checkpoint signals with pathway outputs.

Results

We found that untreated rad26Δ cells were defective for two microtubule-dependent processes: chromosome segregation and morphogenesis. Interestingly, cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP occurred following treatment with microtubule destabilizing drugs, but not during treatment with the genotoxic agent Phleomycin. Cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP depended on Rad24, a 14-3-3 protein also required for DNA structure checkpoints and morphogenesis. Results of over expression and epistasis experiments confirm that Rad26 and Rad24 define a response to microtubule destabilizing conditions.

Conclusion

Two DNA structure checkpoint proteins with roles in morphogenesis define a response to microtubule destabilizing conditions.

Background

The fidelity of cell division and development require genomic stability. Conserved signal transduction pathways called DNA structure dependent checkpoints help ensure genomic stability by detecting unreplicated or damaged DNA. Once detected, the pathways initiate responses that coordinate cell cycle progression with DNA repair processes, maintain telomere structure, induce cellular senescence or cause apoptosis [1,2].

Members of the PI-3 kinase related kinase (PIKK) family are central to DNA structure dependent checkpoints and other stress-responsive pathways [3]. PIKKs are large (>200 kD) proteins that harbor protein kinase activity in a conserved C-terminal catalytic domain that resembles the lipid kinase domain of PI-3 kinases. N-terminal to this kinase domain are protein-interaction and intramolecular folding domains. Following detection of a stress signal, changes in PIKK-protein interactions, folding and subcellular localization allow PIKKs to target downstream effector proteins and coordinate stress responses.

In fission yeast, a PIKK called Rad3 is central to DNA structure dependent checkpoints [4]. Rad3 physically binds to Rad26, a regulatory subunit required for normal levels of Rad3-kinase activity [5,6]. This Rad3/26 checkpoint complex is conserved throughout evolution and exists in humans (ATR/ATRIP), budding yeast (MECl/LCDlDDC2/PIE1), Xenopus (xATR/xATRIP) and possibly filamentous fungi (UvsB/UvsD) [7-12].

These Rad3/26 complexes are sensors that detect and respond to DNA structure checkpoint signals such as double-stranded breaks (DSBs) [13]. Other conserved sensor complexes include the 9-1-1 (Rad9-Radl-Husl) complex and Crb2 [14-20]. The 9-1-1 complex appears to form a PCNA-like clamp that requires Radl7, a dynamic subunit of Replication Factor C, for loading onto DNA. Crb2 contains tandem BRCT-domains and resembles budding yeast Rad9 and human p53BPl. Following DNA damage, these three sensors relocalize independently of each other, suggesting that they detect aberrant DNA structures using parallel pathways [14,21-23]. Exactly how the 9-1-1 and Rad3/26-like complexes initially detect damage is not well understood. They may recognize many different signals, including single-stranded DNA overhangs bound by single-stranded binding protein, and DNA damaged-induced changes in chromatin structure [24,25]. Recent data suggest that the checkpoint signal for Crb2 localization is formed when DSBs alter the structure of nearby histones, and results obtained with p53BPl corroborate this finding [15,26]. Following the production of checkpoint signals and their detection, the events leading to Rad3/26 kinase activation and downstream signal transduction require all three sensor complexes.

Depending on the checkpoint signal, the checkpoint-activated Rad3/26 kinase phosphorylates effector kinases Chkl or Cdsl, which in turn phosphorylate Mikl and Cdc25 [27]. This leads to increased levels of Mikl, a negative Cdc2 regulator, and possibly reduces the phosphatase activity of Cdc25, a positive Cdc2 regulator [28-32]. Checkpoint regulation of Cdc25 may also be mediated by the fission yeast 14-3-3 proteins Rad24 and, to a lesser extent, Rad25 [32,33]. These interactions compartmentalize Cdc25 in the cytoplasm, although the outcome of this is not understood [30]. Recently, it was shown that Rad24 promotes checkpoint-dependent retention of Chkl in the nucleus [34]. Therefore, 14-3-3 proteins may mediate the checkpoint response by affecting the localization of signaling proteins and checkpoint-targets. Interestingly, Rad24 is also required for proper cell morphogenesis, suggesting that this 14-3-3 protein is a component of pathways controlling cell shape [35].

We have been investigating why loss of rad26+ sensitizes cells to the microtubule depolymerizing agent thiabendazole (TBZ) [23]. Specifically, we found that rad26Δ, rad3Δ, rad1Δ and rad9Δ cells were sensitive to TBZ, while hus1Δ and rad17Δ cells shared wild type TBZ-sensitivity. Therefore, TBZ sensitivity does not result from a defective DNA structure checkpoint.

The Mad2-dependent spindle assembly checkpoint restrains metaphase-to-anaphase progression when microtubules are compromised [36]. Experiments have shown that overlap between the spindle assembly and DNA structure checkpoints exist. For example, the spindle assembly checkpoint of fission and budding yeast delays mitotic progression when DNA structure checkpoint mutants are treated with replication inhibitors [37-39]. Thus, the two checkpoint systems cooperate to enhance survival following genotoxic stress. Elements of these pathways may also cooperate to promote mitotic arrest following microtubule stress, which would explain why mutations in some fission yeast DNA structure checkpoint genes cause TBZ sensitivity.

Here, we initiated experiments to characterize the TBZ-sensitivity of rad26Δ cells. Our data show that rad26+ is required for the efficiency of two microtubule-dependent processes, chromosome segregation and cell polarity, and we suspect that defects in both processes may contribute to rad26Δ TBZ-sensitivity. Our data strongly suggest that Rad26 operates independently of the spindle assembly checkpoint to preserve both processes. With regard to the cell polarity defects of rad26Δ cells, our data show that rad26+ is required for proper growth patterns and the polar distribution of actin patches.

We also observed that microtubule-destabilizing conditions caused Rad26-GFP to accumulate in the cytoplasm by a Rad24-dependent manner. Possible outcomes of this response are discussed.

Results

Are rad26Δ cells specifically sensitive to TBZ or generally sensitive to microtubule-destabilizing conditions?

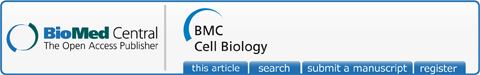

Loss of rad26+ caused TBZ sensitivity [23]. Here, we found that rad26Δ cell growth was also inhibited by 8 μg/ml Carbendazim (MBC), another microtubule-destabilizing compound [45] (Figure 1A). We conclude that the rad26Δ allele sensitizes the growth of fission yeast to different treatments that destabilize microtubules.

Figure 1.

Rad26 responds to conditions that destabilize microtubules. A. rad26Δ cells were sensitive to 8 μg/ml MBC. Cultures of TE236 (rad26+) and TE257 (rad26Δ) were serially diluted onto YE5S and YE5S + MBC plates and grown for 4 days at 30°C. B. TBZ did not cause relocalization of Rad22-GFP. A culture of TE1239 (rad22-gfp) was split and then treated with 20 μg/ml TBZ for five hours, 7.5 μg/ml Phleomycin for two hours, or left untreated. Bars = Std dev C. Rad26-GFP accumulated in the cytoplasm following MBC, but not Phleomycin, treatment. TE236 (rad26+) and TE1197 (rad26-gfp) cells cultured in minimal medium (EMM) were left untreated or treated with 8 μg/ml MBC for 3 hours or 10 μg/ml Phleomycin for 4 hours, fixed with paraformaldehyde and processed for microscopy. The Rad26-GFP signal was similar in live cells (data not shown). Bar = 7 μm.

TBZ does not produce DNA structure checkpoint signals

By disrupting the mitotic spindle and interfering with chromosome metabolism, microtubule-destabilizing agents could conceivably affect the integrity of DNA and compromise rad26Δ cell growth. Rad22 is a homologous recombination protein that localizes to discrete foci when genotoxins cause double strand breaks or stall replication [22,46,47]. If microtubule-destabilizing conditions produce these effects, then Rad22-GFP foci will form following TBZ treatment. We found that Rad22-GFP foci formed following treatment with the DNA damaging agent Phleomycin, but not following TBZ treatment (Figure 1B). Therefore, double strand breaks and stalled replication forks are not responsible for the sensitivity of rad26Δ cells to TBZ, consistent with the previous observation that rad17Δ and hus1Δ cells were not TBZ-sensitive [23].

Rad26-GFP accumulates in the cytoplasm during MBC treatment

The data above suggest that Rad26 may participate in a cellular response to microtubule destabilizing conditions. To investigate this idea, we tested if Rad26-GFP localization changed during treatment with microtubule-destabilizing drugs (Figure 1C). Importantly, our rad26-gfp strain retained normal sensitivity to TBZ and MBC (data not shown). In untreated cells, dots of Rad26-GFP were observed in the nuclear region, consistent with previous results [23]. We also noticed that these cells contained a fluorescent cytoplasmic signal that was absent in the untagged control strain. At the present time, we cannot say for certain if this signal represents Rad26-GFP as opposed to background noise. Following 3 hours of MBC treatment, Rad26-GFP accumulated in the cytoplasm; earlier time-points revealed that cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP could be detected within 20 minutes of MBC addition (below, Figure 8). TBZ-treatment also caused this redistribution of Rad26-GFP (data not shown). We did not detect redistribution of Rad26-GFP to the cytoplasm following treatment with Phleomycin. These data demonstrate that Rad26 localization changes in response to drugs that disrupt microtubules.

Figure 8.

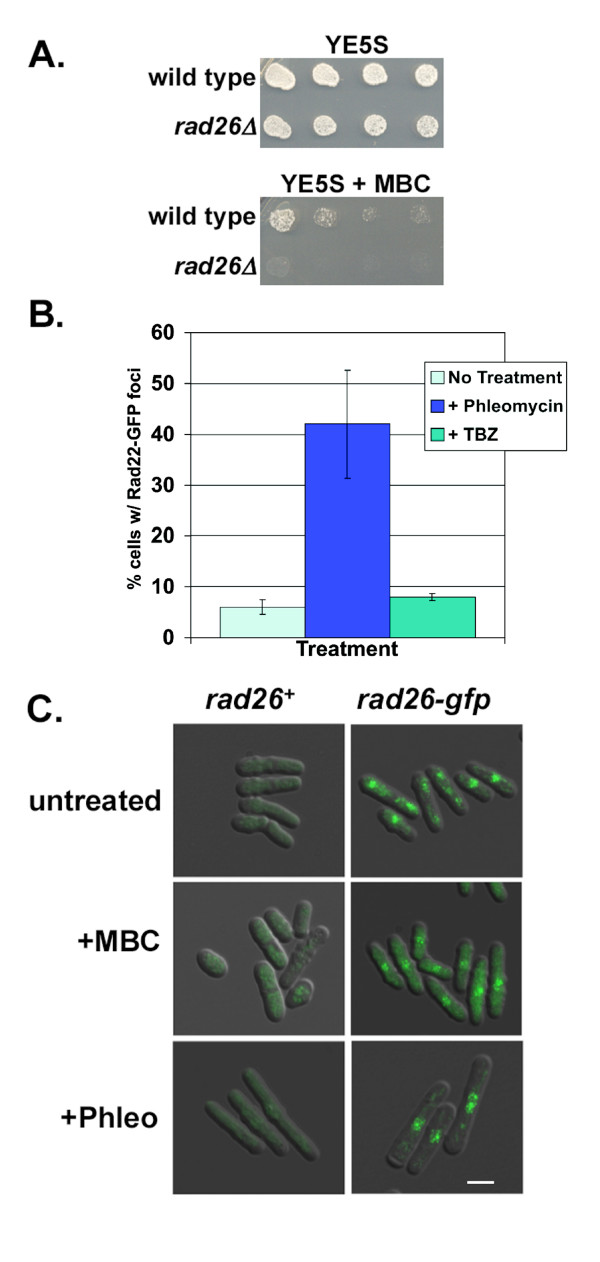

rad24+ was required for normal cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP after 20 minutes of MBC treatment. Cultures of rad26-gfp (TE1197), rad25Δ rad26-gfp (TW1237) and rad24Δ rad26-gfp (TW1238) in liquid EMM minimal media were left untreated or treated with MBC for 20 minutes. The figure was made by merging DIC and GFP images. Arrows point to untreated rad25Δ rad26-gfp cells that have cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP signal. Notice that rad24Δ cells are more spherical than rad24+ and rad25Δ cells. The percentage of cells containing cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP signal is shown (N > 100). Bar = 5 μm.

The spindle assembly checkpoint of rad26Δ cells appears to operate normally during TBZ treatment

The spindle assembly checkpoint prevents mitosis when the spindle is compromised [48]. Defects in this pathway lead to (1) undelayed progression through mitosis, (2) premature sister chromatid separation and (3) chromosome loss during microtubule destabilizing conditions. We tested if rad26Δ cells displayed these phenotypes during TBZ treatment to investigate if Rad26 is a component of the spindle assembly checkpoint.

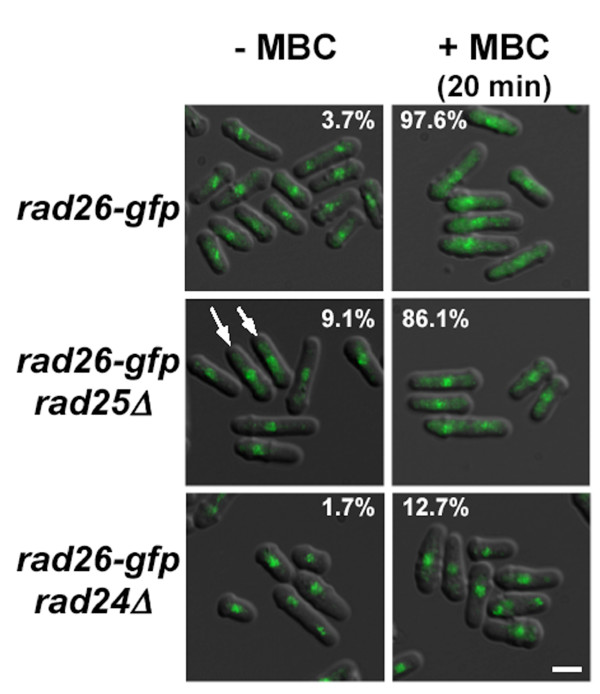

First, we tested if rad26+ was required to delay septation during TBZ treatment. The temperature sensitive (ts) cdc25.22 allele was used to synchronize cells in G2, and it is known that the spindle assembly checkpoint delays septation when cdc25.22 cells are released into TBZ-medium [49,50]. Following release from the G2-block, we found that untreated rad26Δ cells septated slightly faster than rad26+ cells (Figure 2A). During TBZ treatment, rad26Δ cells once again septated slightly faster than rad26+ cells. However, TBZ-treated rad26Δ and rad26+ cells delayed the onset of septation with similar kinetics. Therefore, rad26+ is not required to delay septation during TBZ treatment.

Figure 2.

The spindle assembly checkpoint of rad26Δ cells appears functional. A. rad26Δ cells delayed mitosis during TBZ treatment. Cultures of TW1261 (cdc25.22 rad26+) and TW1262 (cdc25.22 rad26Δ) were shifted to 37°C for 4 hours to arrest cells in G2. TBZ (20 μg/ml) was added to respective cultures 30 minutes before shifting to 30°C and releasing into mitosis. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with Calcofluor to visualize septa. B. Chromosome stability was not affected in TBZ-treated rad26Δ cells. The adenine-marked minichromosome of TE787 (rad3Δ), TW1222 (wild type) and TW1224 (rad26Δ) was used to assay chromosome loss following 8 h of TBZ treatment. Bars = Std dev C. Chromosome separation was restrained in rad26Δ cells during TBZ treatment. Cultures of TW1261 and TW1262 were shifted to 37°C for 4 hours and arrested in G2. TBZ was added to respective cultures 30 minutes before shifting to 26°C and releasing into mitosis. Cells were fixed in methanol; chromosome separation was monitored using the Cen1-GFP marker. D. The septation index of asynchronous rad26Δ cultures is elevated. Asynchronous cultures of rad26+ (TE236) and rad26Δ (TE257) cells were split and left untreated or treated with 20 μg/ml TBZ for five hours, fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with Calcofluor. The septation index is the percentage of septated cells in the culture.

Second, we tested if rad26+ prevents chromosome loss during TBZ treatment (Figure 2B). Cells containing an adenine-marked minichromosome were cultured in rich liquid medium for 40 hours [51]. Cultures were then split in half; one half was left untreated for 8 hours, and the other half was treated with 20 μg/ml TBZ for 8 hours. We observed that 0% of rad26+, 5% of rad26Δ and 2% of rad3Δ cells experienced chromosome loss during the unperturbed growth period. The 5% difference between rad26Δ and rad26+ cells was statistically significant (p < 0.05; chi-squared), demonstrating that loss of rad26+ causes chromosome loss during normal cell growth. Following TBZ treatment, 29% of rad26+, 34% of rad26Δ and 21% of rad3Δ cells lost the minichromosome. As the difference between rad26+ and rad26Δ cells was still 5%, loss of rad26+ did not exacerbate chromosome loss during TBZ treatment. This result suggests that rad26+ is not required to prevent chromosome loss under microtubule-destabilizing conditions.

Third, we tested if rad26+ was required to prevent sister chromatid separation during TBZ treatment. We followed chromatid separation using a strain marked with a GFP-labeled chromosome 1 (Cenl-GFP) [52]. One GFP focus is visible during interphase and early mitosis when the sister chromatids are too close together to resolve individual Cenl-GFP signals using conventional fluorescence microscopy. Two foci become visible when sister chromatid separation occurs. Cenl-GFP cells were synchronized in G2 using the cdc25.22 allele before release into mitosis. We observed that sister chromatid separation was accelerated in untreated rad26Δ cells relative to untreated rad26+ cells (Figure 2C). Taking this result into consideration, both rad26Δ and rad26+ cells delayed sister chromatid separation with similar kinetics following release into media containing TBZ (Figure 2C). Therefore, rad26+ is not required to delay chromosome separation during TBZ treatment.

Figures 2A and 2C showed that mitotic events were accelerated in rad26Δ cells. To investigate if these accelerations were a function of cdc25.22 synchronization, we tested if loss of rad26+ affected the rate of cell cycle progression in untreated or TBZ-treated asynchronous cultures by calculating the percentage of cells with a septum (Figure 2D). We found that the septation index of rad26Δ cells was slightly higher that that of rad26+ cells, suggesting that loss of rad26+ advances the timing of cell cycle progression. The septation indices of both asynchronous cultures dropped similarly following TBZ-treatment, again demonstrating that rad26Δ cells can restrain septation during treatment.

The data of Figure 2 demonstrate that rad26+ is not required to delay mitotic progression or prevent chromosome segregation during TBZ treatment, suggesting that rad26+ is not a component of the spindle assembly checkpoint.

Loss of rad26+ affects cell polarity and the bipolar growth axis

In addition to their critical role during chromosome segregation, microtubules are also important for generating and maintaining cellular morphology [53]. Fission yeast are cylindrically shaped cells that grow bipolarly from each end, and cytoplasmic microtubules mediate the transport of growth axis determinants to these ends. TBZ may affect the growth of rad26Δ cells if rad26+ is involved in the establishment or maintenance of morphology.

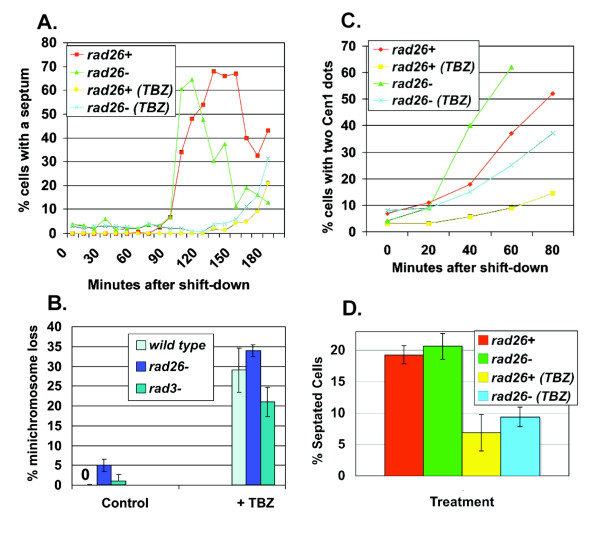

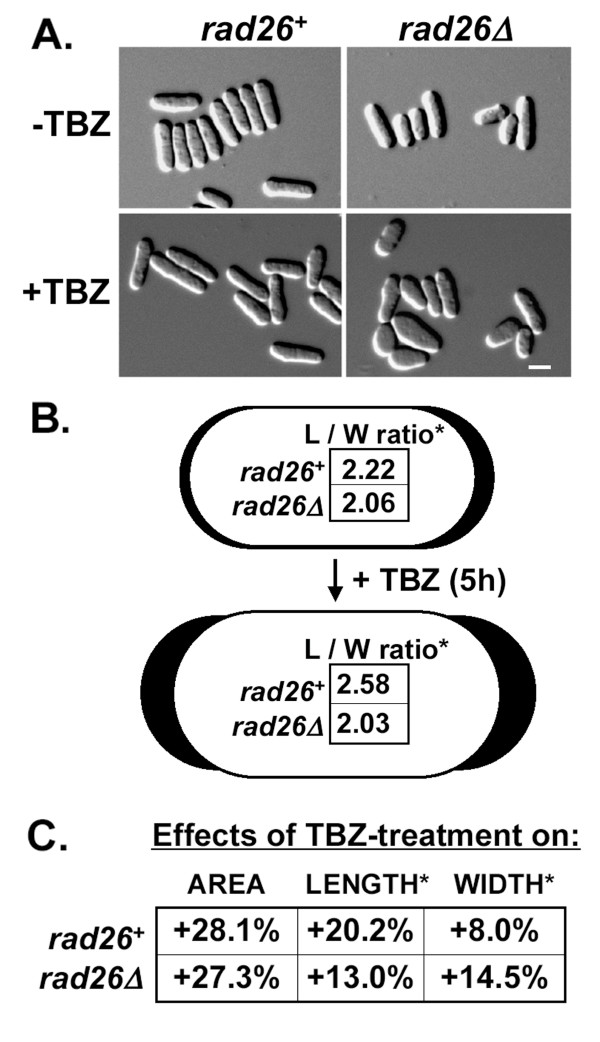

To determine if TBZ affected the morphology of rad26Δ cells, we first characterized the morphology of untreated cells by taking length, width and area measurements from acquired images. Our data show that the length of untreated rad26+ cells was 2.22-fold greater than their width (L/W ration; Figure 3A,B). Following 5 hours of TBZ-treatment, the length of rad26+ cells increased faster than their width, resulting in a higher L/W ratio of 2.58. Over the course of treatment, the total area of rad26+ cells increased roughly 28% due to a 20% increase in length and an 8% increase in width (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

TBZ affected the polarity of rad26Δ cells. A. Images of untreated and TBZ-treated rad26+ and rad26Δ cells. Cultures of rad26+ (TE236) and rad26Δ (TE257) cells were split and left untreated or treated with 20 μg/ml TBZ for five hours, fixed with paraformaldehyde and observed using DIC. B. Interpretive diagram showing that rad26Δ cells were significantly wider (*) than rad26+ cells. The dimensions of untreated and TBZ-treated cells were quantified using Leica FW4000 image analysis software. The length-to-width (L/W) ratios were calculated and presented here in pictorial representations of rad26+ (outlined in black) and rad26Δ (outlined in white) cells. C. The width of rad26Δ cells increased (+) during TBZ-treatment.

Measurements of untreated rad26Δ cells demonstrated that they were shorter, but proportionally wider (LAV = 2.06) than rad26+ cells (Figures 3A,B). Following 5 hours of TBZ treatment, the area of rad26Δ cells increased ~27% due to a 13% increase in length and a ~15% increase in width, and the cells retained a LAV of 2.03 (Figure 3C). Therefore, while rad26+ and rad26Δ cells experienced very similar area increases during treatment, rad26+ cells experienced greater length increases while rad26Δ cells experienced greater width increases. These morphological defects were not caused by cell death, since viability assays showed that both wild type and rad26Δ cells retained greater than 80% viability at 8 hours of TBZ treatment (data not shown). Together, the data of Figure 3 demonstrate that loss of rad26+ affects cell shape and the bipolar growth axis.

Other morphological defects associated with rad26+

We also observed rad26Δ-dependent polarity defects during the cdc25.22 block and release experiments of Figure 2. The great majority of rad26+ cdc25.22 cells (99.6%) retained a long, cylindrical shape during the G2 arrest (Figure 4A). The great majority of rad26Δ cdc25.22 cells (98.1%) also displayed this normal morphology, although 1.9% of these cells displayed abnormal morphological characteristics including branched tips and abnormal cell wall deposition as judged by Calcofluor staining (Figure 4B–D). These morphological differences between the rad26+ cdc25.22 and rad26Δ cdc25.22 cells were very modest but significant (p < 0.05; t-test). Therefore, loss of rad26+ has very subtle, yet significant affects on the shape of G2-arrested cdc25.22 cells.

Figure 4.

Additional polarity defects associated with loss or over expression of rad26+. A. – D. Prolonged G2 arrest affected the morphology of rad26Δ cells. A. rad26+ cdc25.22 (TW1261) and B. to D. rad26Δ cdc25.22 (TW1262) cells were arrested at 37°C for 3 h, fixed and stained with Calcofluor. Bar = 8 μm. E. and F. rad26Δ exacerbated the polarity defects of kin1Δ cells. E. kin1Δ (TE550) and F. kin1Δ rad26Δ were grown in liquid culture, fixed with paraformaldehyde and observed with brightfield. Bar = 10 μm. G. – I. Over expression (OE) of rad26+ caused polarity defects. G. rad26+ with empty vector (TE236 with pTE102), H. rad26+ OE rad26+ (TE236 with pTE169) and I. rad3Δ OE rad26+ (TE570 with pTE169) cells were grown in promoter-derepressing conditions for 20 hours, fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI. The arrow points to a cell with an abnormal number of nuclei. Bar = 10 μm.

We tested if rad26Δ-dependent morphology defects would exacerbate those of a morphology mutant. Kin1 is a conserved serine-threonine kinase that localizes to new cell ends and is required for the proper distribution of actin patches and overall cell symmetry; its loss results in abnormally shaped cells [54-56]. Under normal growth conditions, we found that 19.1 + 4.3% of kin1Δ cells were round and had thus completely lost polarity, while 45 ± 6.1% of rad26Δ kin1Δ cells were round (Figures 4E,F). Again, the rad26Δ allele caused a nearly 2-fold difference in morphological characteristics (p < 0.05). Therefore, loss of rad26+ exacerbates the polarity defects of kin1Δ cells.

If rad26+ influences cell polarity, then over expression of rad26+ may disrupt it. We used the nmt thiamine-repressible promoter to drive expression of exogenous rad26+ cDNA [41,57]. While rad26+ cells with empty vector maintained wild type morphology, 22% of cells over expressing rad26+ lost polarity and became abnormally shaped and spherical (Figure 4G,H). This effect was independent of Rad3, because 20% of rad3Δ cells over expressing rad26+ displayed similar morphological abnormalities (Figure 4I). In addition to polarity defects, 18% of cells over expressing rad26+ contained abnormal numbers of nuclei (Figure 4H arrow; Figure 4I) or abnormal nuclear morphologies (Figure 4I). We conclude that over expression of rad26+ influences both cell morphology and DNA metabolism.

rad26+ is required for the polar distribution of actin patches, but not for gross microtubule architecture

The results presented thus far demonstrate that rad26+ is required for proper cell morphogenesis. To test if rad26+ is required for the structure or arrangement of microtubules, we examined microtubule architecture in untreated and TBZ-treated rad26Δ cells. Microtubules were visualized using gfp-a2-tubulin driven by a thiamine repressible promoter [42]. We did not observe any differences between the microtubules of untreated and TBZ-treated rad26+ and rad26Δ cells (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the number of microtubules per cell and the length of microtubules did not differ between untreated and TBZ-treated rad26+ and rad26Δ cells (data not shown). Therefore, gross microtubule architecture was unaffected by loss of rad26+.

Figure 5.

Loss of rad26+ affected the polar distribution of actin patches but not gross microtubule architecture. A. Gross microtubule architecture was not affected by loss of rad26+. rad26+ (1226) and rad26Δ (1248) cells expressing ectopic atb2-gfp were grown in EMM + 0.2 μM thiamine. TBZ (20 μg/ml) was added to half of each culture for 5 hours, after which cells were fixed with methanol and processed for microscopy. Bar = 4 μm B. rad26+ is required for the polar distribution of actin patches. rad26+ (TE236) and rad26Δ (TE257) cells were grown in YE5S liquid. Half of each culture was treated with 20 μg/ml TBZ for 5 hours before fixing and staining with FITC-Phalloidin (see Methods). Bar = 5 μm C. A diagrammatic representation of polar and non-polar actin patch distributions. D. Graphical representation of data collected from B.

Actin is also required for fission yeast polarity [58]. Actin cables are typically oriented along the fission yeast growth axis and patches typically localize to sites of polarized growth at cell ends [59,60]. This bipolar localization of actin patches depends on microtubules and the growth axis determinants that they deliver to cell ends [61]. We used FITC-conjugated phalloidin to test if actin architecture was affected by loss of rad26+ (Figure 5B–D). In untreated rad26+ cells, 15% of rad26+ cells contained actin patches that were delocalized from the cell ends. Following TBZ treatment, 24% of rad26+ cells contained delocalized actin patches. In untreated rad26Δ cells, 38% of cells contained delocalized patches. TBZ treatment increased the percentage of cells with delocalized patches to 53%. Because we did not detect a difference between the number of patches in untreated and TBZ-treated rad26+ and rad26Δ cells (data not shown), we conclude that loss of rad26+ affects the establishment or maintenance of actin patches at polar growth sites.

Over expression of rad24+ specifically rescued the TBZ-sensitivity of rad26Δ cells

We screened a cDNA library (gift of A. Yamamoto) for those that when over expressed (OE) allowed rad26Δ cells to grow on TBZ. Of 10,000 transformants, we identified four non-redundant cDNAs. Three of these cDNAs also rescued the TBZ-growth defects of mad2Δ cells and nda2-KM52 cells, which harbor a cold-sensitive α-tubuiln allele (Figure 6A) [62,63]. These three cDNAs encoded N-term or C-term fragments of putative microtubule binding proteins, and we suggest that over expression of each may have counter-acted the microtubule destabilizing effects of TBZ. OE rad24+ specifically rescued the growth defect of rad26Δ cells, and not mad2Δ or nda2-KM52 cells, on TBZ (Figures 6A,B; full length rad24 cDNA was recovered in the screen). Rad24 is a 14-3-3 protein required downstream of Rad26 in the DNA structure checkpoints; however OE rad24+ also failed to rescue the growth of rad26Δ cells on plates containing the DNA replication inhibitor, hydroxyurea (HU; data not shown). We conclude that OErad24+ specifically suppresses the TBZ sensitivity of rad26Δ cells.

Figure 6.

Over expression of rad24 cDNA rescued the TBZ-sensitivity of rad26Δ cells, but not mad2Δ cells. A. Results of the over expression (OE) screen (see Methods). Four cDNAs suppressed the TBZ-sensitivity of rad26Δ cells, and three of these also suppressed the TBZ-sensitivities of nda2KM52 and mad2Δ cells. B. Only OErad24+ specifically suppressed the growth of rad26Δ cells on TBZ. Wild type (TE236), rad26Δ (TE257) and mad2Δ (TW1219) were transformed with a plasmid containing inducible rad24 cDNA (pTW909) and streaked onto EMM and EMM + TBZ medium containing the vital stain Phloxin B. Pictures were taken after 3 days of growth at 30°C. Upper left = EMM; Upper right = EMM + TBZ (20 μg/ml) C. rad24Δ cells were sensitive to TBZ. Wild type (TE236), rad26Δ (TE257), rad24Δ (TE465), rad25Δ (TE464) and chk1Δ cds1Δ (TE892) were streaked onto YE5S (top) and YE5S + 20 μg/ml TBZ (bottom) and incubated at 30°C for three days.

rad24Δ and rad26Δ alleles may confer TBZ sensitivity by the same mechanism

Next we tested if loss of rad24+ caused TBZ sensitivity. Figure 6C shows that rad24Δ cells were also TBZ-sensitive. Since Rad24 is a downstream signal transducer in the DNA structure checkpoint pathway, we tested if loss of other downstream components would also result in TBZ sensitivity. We found that chk1Δ cds1Δ cells were only slightly sensitive to TBZ. Loss of rad25+, which encodes the other 14-3-3 protein of fission yeast, also conferred less TBZ-sensitivity than loss of rad24+. Therefore, loss of rad26+ or rad24+ causes TBZ-sensitivity by a mechanism that may be partially dependent on downstream DNA structure checkpoint elements.

We used epistasis to address if the rad24Δ and rad26Δ alleles conferred TBZ sensitivity by the same mechanism. Strains were spotted onto different concentrations of TBZ to determine if the rad26Δ rad24Δ double mutant was more or less TBZ sensitive than the single mutants. We observed that the double mutant was no more sensitive than the rad24Δ single mutant (Figure 7A). Therefore, the rad24Δ and rad26Δ alleles may confer TBZ sensitivity by the same mechanism.

Figure 7.

The rad26Δ and rad24Δ alleles may cause TBZ-sensitivity by a pathway that is independent of the cytokinesis checkpoint. A. The rad26Δ rad24Δ strain did not display an additive phenotype on TBZ medium. Cultures of wild type (TE236), rad26Δ (TE257), rad24Δ (TE465) and rad26Δ rad24Δ (TW1235) were serially diluted and manually spotted onto YE5S and YE5S + 8, 14 and 16 μg/ml TBZ. Pictures were taken after 3 days of growth at 30°C. B. rad24Δ, but not rad26Δ, was sensitive to LatA. Cultures were spotted onto YE5S plates + 0.5 μM LatA. C. The cytokinesis checkpoint of rad26Δ cells was intact. Liquid YE5S cultures of wild type (TE236), rad26Δ (TE257) and rad24Δ (TE465) were left untreated or treated with 0.2 μM LatA for 5 hours, fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI.

rad24Δ and rad26Δ alleles confer TBZ sensitivity by a mechanism independent of the cytokinesis checkpoint

Rad24 is a component of the cytokinesis checkpoint that delays entry into the next mitotic cycle when the actinmyosin cytokinetic ring is compromised [64,65]. For example, when construction of the ring is jeopardized by Latrunculin A (LatA) treatment, wild type cells delay cell cycle progression as binucleate cells, while rad24Δ cells pass through the next round of mitosis and become multinucleate. Perhaps TBZ affects the structure or function of the actomyosin ring, and perhaps rad26+ is a component of this cytokinesis checkpoint. If so, that would explain why rad26Δ and rad24Δ cells are TBZ-sensitive.

To test if rad26+ is a component of the cytokinesis checkpoint, cells were plated to LatA. While rad24Δ cells were LatA sensitive, rad26Δ cells were not (Figure 7B). Next, we tested if rad26Δ and rad24Δ cells became multinucleate (3 or more nuclei) following LatA treatment. As shown in Figure 7C, LatA treated rad24Δ cells became multinucleate after 5 hours, while rad26Δ cells did not. We conclude that rad26+ is not a component of the cytokinesis checkpoint. These data suggest that loss of rad26+ and rad24+ cause sensitivity to mictrotuble-destabilizers by a mechanism independent of the cytokinesis checkpoint.

rad24+ is required for cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP during MBC treatment

14-3-3 proteins can affect signaling pathways by altering the cellular localization of proteins [66]. We tested if rad24+ and/or rad25+ were required for efficient cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP during MBC treatment (Figure 8). A small percentage (3.7%) of untreated control cells contained cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP signal, while 97.6% of MBC-treated cells accumulated cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP signal within 20 minutes of treatment. In a rad25Δ background, 9.1% of untreated cells and 86.1% of MBC-treated cells contained cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP signal. In a rad24Δ background, 1.7% of untreated and 12.7% of MBC-treated cells contained cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP signal. Importantly, viability assays showed that rad24Δ cells retained greater than 95% viability following 1 hour of MBC or TBZ treatment (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that efficient cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP during MBC treatment depends on rad24+ and, to a much lesser extent, rad25+.

Discussion

Rad26 and Rad24 participate in a signaling pathway that responds to microtubule destabilizing conditions

The evidence presented demonstrates that Rad26 and Rad24 operate in a pathway that responds to microtubule destabilizing conditions. First, loss of rad26+ or rad24+ caused sensitivity to microtubule destabilizing drugs. Second, over expression of rad24+ rescued the TBZ-sensitivity of rad26Δ, but not mad2Δ or nda2-KM52, cells. Third, the rad24Δ single mutant and the rad26Δ rad24Δ double mutant shared similar TBZ-sensitivity. And fourth, rad24+ was required for efficient cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26-GFP that occurred following MBC treatment.

Is this rad26+ and rad24+ dependent pathway responding to spindle damage, morphological defects, or problems in other microtubule-dependent structures and/or processes? Our data suggest that this pathway does not respond to spindle damage because TBZ-treated rad26Δ and rad26+ cells delayed septation and chromosome separation with similar kinetics and experienced similar frequencies of minichromosome loss. Furthermore, over expression of rad24+ failed to rescue the TBZ-sensitivity of mad2Δ cells. To date, however, we have only detected Rad26 in the nucleus of untreated cells, consistent with a role for Rad26 in surveying nuclear defects associated with microtubule stress. Therefore, our data do not rule out the possibility that this pathway responds to spindle damage.

Another possibility is that this pathway responds to loss of microtubule-dependent polarity structures. In this regard, TBZ treatment exacerbated rad26Δ defects associated with bipolar growth and the distribution of actin patches. Loss of rad26Δ also intensified the polarity defects of kin1Δ cells, again suggesting that Rad26 is required for polarity maintenance. Whereas the polarity defects ascribed here to rad26Δ cells are somewhat subtle, those of rad24Δ cells are obvious, as the cells have a more spherical appearance. Therefore, rad26+ and rad24+ may define a pathway that responds to defects in microtubule-dependent polarity structures. Part of the pathway's response may occur in the cytoplasm where Rad26-GFP accumulates. A clearer picture of this pathway will develop when we can define the purpose that cytoplasmic accumulation of Rad26 serves.

Do errors in DNA metabolism caused by loss of rad26+ lead to morphological defects?

We have shown here that rad26Δ cells lose a minichromosome at an elevated rate. Untreated rad26Δ, rad3Δ, rad1Δ, rad9Δ, hus1Δ and rad17Δ cells also have an increased number of Rad22 foci, suggesting that they accumulate spontaneous errors in DNA metabolism [22]. In S. cerevisiae, mutations in MEC1rad3+, DDC2rad26+ and MEC3hus1+ cause upto 200-fold increases in gross chromosomal rearrangements, while ablation of mouse HUS1 causes an array of chromosomal rearrangements [67,68]. Errors in DNA metabolism are therefore a common consequence of checkpoint loss.

However, our data do not support the idea that genomic errors caused by loss of rad26+ affect morphology. First, rad26Δ cells displayed specific defects in actin, and not microtubule, patterns. If gross errors in DNA metabolism affect morphology, then we would expect this effect to be broad and inclusive of both cytoskeletal elements. And second, loss of rad26Δ compromised the polarity of kin1Δ and G2/M arrested cdc25.22 cells, neither of which is known to accumulate genomic errors in DNA.

It is important to point out that ATM, a human PIKK involved in DNA structure checkpoint pathways, localizes to the cytoplasm of mouse Purkinje cells and in the endosomes of murine cerebellocortical neurons, and ATM mutations lead to loss of Purkinjie cells and neurodegeneration in humans [69-71]. In these contexts, cytoplasmic ATM is thought to influence the metabolism of reactive oxygen species, and loss of this activity may cause accumulation of oxidative stress and genomic lesions that lead to disease [72-75]. In addition, ATM was recently shown to translocate to the cytoplasm following the production of DSBs [76]. Again, cytoplasmic ATM is thought to protect cells, or influence their recovery, from genomic stress. In this report we found that cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP specifically accumulated following microtubule, not genomic, stress. Therefore, we predict that the outcome will influence mechanisms that protect against loss of microtubule dependent processes such as polarity.

An evolutionarily conserved role for DNA structure checkpoint elements in polarity maintenance?

Rad24 is the only fission yeast DNA structure checkpoint component with a documented role in polarity, as rad24Δ cells are more spherical than wild type (Figure 8) [35]. It is a member of the 14-3-3 family associated with the dynamic nucleoplasmic shuttling of proteins with phospho-serine and -threonine motifs [77]. In humans, >200 proteins bind a 14-3-3 phosphopeptide binding site, including some implicated in controlling actin dynamics [78]. Over expression of ArtA, an A. nidulans 14-3-3 gene, inhibits polarization and is therefore linked to the morphogenesis of filamentous fungi [79]. While little is known about how 14-3-3 proteins like Rad24 affect polarity, the evidence presented here suggest that Rad26 may be involved.

Roles in morphology have also been attributed to ATM and AtmA, an A. nidulan's PIKK that is homolgous to ATM and also required for DNA structure checkpoints [80]. The ΔatmA cells displayed defects in establishing a normal growth axis at hyphal tips and incorporated cell wall material at subapical regions. The hyphal tips of these cells also curled backwards as opposed to radiating outward in a straight line like wild-type. Strikingly, the microtubules of ΔatmA cells failed to converge at hyphal tips. In addition, altered morphology and altered actin filament patterns have been observed in ataxia-telangiectasia fibroblasts that harbor a mutation in ATM [81]. Interestingly, the microtubule arrays of these cells appeared normal. ATM has also been shown to physically interact with CKIP-1, a regulator of the actin cytoskeleton, and affect RhoA activity during the DNA damage response [82,83]. Together, these observations suggest that DNA structure checkpoint elements share an evolutionarily conserved role in regulating cell morphology.

Why do untreated rad26Δ cells have a 5% elevated-rate of minichromosome loss?

In addition to polarity defects, untreated rad26Δ cells experienced minichromosome loss. We present four of many possible explanations to account for this. First, Cdc2 activity may be deregulated in rad26Δ cells, since rad26+ and other elements of the DNA structure checkpoints are negative regulators of Cdc2. Deregulation of Cdc2 could conceivably lead to premature activation of Cdc2 and premature entry into mitosis.

Second, rad26Δ cells may have abnormal cohesion. In this case, rad26+ may be required for proper heterochromatin structure, since (1) rad3+ and rad26+ are required for telomere structure, (2) rad3+ influences telomeric silencing, (3) overproduced Rad3 associates with telomeric DNA and (4) rad26Δ cells exhibit minichromosome loss (Figure 2B) [84,85]. Perhaps loss of rad26+ affects the formation of heterochromatin that is known to nucleate cohesion assembly [86]. In turn, compromised cohesion could accelerate chromosome separation.

Third, Rad26 may regulate spindle behavior. In this regard, Mecl of budding yeast prevents precocious chromosome segregation during a block to DNA replication by affecting spindle elongation as opposed to mitotic entry [87]. It is possible that loss of rad26+ affects the dynamics of spindle elongation and leads to chromosome loss by a similar mechanism.

And fourth, yeast spindle alignment is dependent on interactions between microtubules and cell polarity cues, including those of the cortical actin cytoskeleton [88-90]. The rad26Δ-polarity problems may affect these interactions and lead to chromosome segregation errors. Our speculative model follows, whereby Rad26 and Rad24 may define a pathway required for polarity maintenance. Like DNA structure checkpoint pathways, this pathway may ultimately function to preserve genomic integrity.

Conclusion

A novel role for DNA structure checkpoint elements: responding to microtubule destabilizing conditions

The data presented here show that two elements of fission yeast DNA structure checkpoints (Rad26 and Rad24) define a pathway that responds to microtubule destabilizing conditions. We predict that the outcome may influence mechanisms that protect against loss of microtubule-dependent processes like polarity.

Methods

Strains, growth conditions and chemical stock solutions

The strains used in this study (Table 1) were grown under standard conditions unless noted otherwise [40]. Chemical reagents and stock solutions follow: Thiabendazole (TBZ; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was stored as a 20 mg/ml Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) solution; Carbendazim (MBC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as a 8 mg/ml DMSO solution; Phleomycin (Research Products International, Mt. Prospect, IL) as a 5 mg/ml DMSO solution; Latrunculin A (LatA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as a 10 mM DMSO solution; and fluorescein (FTTC)-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as a 200 U/ml methanol solution.

Table 1.

Fission yeast plasmids and strains

| Plasmid/Strain | Genotype | Origin |

| pTE169 | nmt-rad26 (cDNA) Leu+ | al-Khodairy et al., 1994 |

| pTE102 | nmt (empty vector) Leu+ | Maundrell, 1993 |

| pTW909 | nmt-rad24 (full length cDNA isolated from over expression screen, Figure 8) Leu+ | This study |

| TE236 | leul-32 ura 4-d18 h- | Kostrub et al., 1998 |

| TE257 | rad26::ura4+ade6-704 leul-32 ura4-D18 h- | Al-Khodairy et al. (1994) |

| TE369 | nda2-KM52 leu1-32 h+ | Toda et al., 1983 |

| TE464 | rad25::ura4+ ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 h+ | Ford et al., 1994 |

| TE465 | rad24::ura4+ ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 h+ | Ford et al., 1994 |

| TE550 | kin1::LEU2 ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-294 h90 | Levin and Bishop, 1990 |

| TE570 | rad3::ura4+ ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 h- | Bentley et al., 1996 |

| TE583 | cdc25-22 h- | Nurse et al., 1976 |

| TE787 | rad3::ura4+ ade6-M210 [Ch16 ade6-216] | Gift of CR Chapman |

| TE892 | chk1::ura4+ cds1::ura4+ ura4-D18 leu1-32 | Gift of C. Kostrub |

| TE1197 | rad26::rad26-gfp (G418R) leu1-32 ura4-D18 h- | |

| TW1207 | leu1-, ura-, Cen1-GFP [dis1 promoter 5'-lacI-gfp] (at his7 locus) lacO repeat (at lys1 locus which is 30 Kb from Cen1) h+ | Nabeshima et al., 1998 |

| TW1219 | mad2::ura4 ura4-D18 leu1-32 h- | Sugimoto et al., 2004 |

| TW1222 | [Ch16 ade6-216] ade6-210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | Javerzat et al., 1996 |

| TW1224 | rad26::ura4+ ade6-210 ura4-D18 [Ch 16 ade6-216] | This study |

| TW1226 | leu1-32 pDQ105 (LEU+ nmt-atb2-gfp) h- | Ding et al., 1998 |

| TW1235 | rad26::ura4+ rad24::ura4+ | This study |

| TW1237 | rad25::ura4+ rad26::rad26-gfp (G418R) | This study |

| TW1238 | rad24::ura4+ rad26::rad26-gfp (G418R) | This study |

| TW1239 | rad22::rad22-gfp (kanr) ade6-210 leu1-32 h- | Gift of Miguel Ferrerira |

| TW1248 | rad26::ura4+ ura4-D18 ade6-708 pDQ105 (LEU+ nmt-atb2-gfp) h- | This study |

| TW1261 | cdc25-22 Cen1-GFP | This study |

| TW1262 | cdc25-22 rad26::ura4+ Cen1-GFP | This study |

Physiological methods

The spot assays (Figure 1A and Figure 7A,B) were performed as follows. Cultures grown to an optical density (OD) of 0.3 in YE5S liquid medium were serially diluted by a factor of 5. From each dilution, 5 μl aliquots were manually spotted to plates using a pipetman. Spot assays were repeated twice with very similar results.

To compare viabilities of rad26Δ (TE257), rad24Δ (TE465) and wild type (TE236) cells, cultures grown to an OD of 0.3 in liquid YE5S were left untreated or treated with 20 μg/ml TBZ or 8 μg/ml MBC for 8 hours. After each hour of treatment, cell densities were determined using a hemocytometer and culture dilutions were plated onto YE5S for 2 days at 30°C. This time-course viability experiment was repeated twice, and 300 cells were counted after each trial.

To test if Rad22-GFP relocalized in response to TBZ and Phleomycin (Figure 1C), cells were grown to an OD of 0.3 in liquid YE5S. Phleomycin was added to cultures at a concentration of 7.5 μg/ml for 2 hours, and TBZ to a concentration of 20 μg/ml for 4 hours. The Rad22-GFP signal was observed after cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (see Microscopy below). Two trials were performed, and 200 cells were scored per trial.

Block and release experiments using cdc25.22 (Figure 2A,C) were performed as follows. Control (untreated) cells in liquid YE5S were shifted to 37°C for 4 hours, washed with 26°C liquid medium, and released into untreated medium at either 30°C (Figure 2A) or 26°C (Figure 2C). Experimental (TBZ-treated) cells in liquid YE5S were also shifted to 37°C for 4 hours, and TBZ (20 μg/ml) was added during the last 30 minutes of this 4 hour period. Cells were then released into either 30°C (Figure 2A) or 26°C (Figure 2C) medium containing 20 μg/ml TBZ. Septa were observed using Calcofluor (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 0.1 μg/ml to stain paraformaldehyde-fixed cells, and Cenl-GFP foci were observed in Methanol-fixed cells. Each of these experiments (Figure 2A,C) was repeated twice, and 200 cells were scored at each time point. The overall trends of each repeated experiment were nearly identical (data not shown).

Chromosome stability assays (Figure 2B) were performed using cells cultured in YE5S liquid medium for 40 hours. Cultures were then split in half; one half was left untreated for 8 hours, and the other half was treated with 20 μg/ml TBZ for 8 hours. These cultures were then diluted and cells were plated to YE5S medium for 2 days at 30°C. Cells were then replica-plated to EMM minimal media – adenine for 2 days at 30°C. Pink cells unable to grow well on these EMM – adenine plates had lost the minichromosome. Three trials were performed, and 500 cells were scored per trial.

Cytology of cdc25.22 and cdc25.22 rad26Δ cells (Figure 4A–D) was examined after incubation at 37°C for 3 hours. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with Calcofluor. Data were collected from three experiments, and 300 cells were scored during each experiment.

Cytology of kin1Δ and kin1Δ rad26Δ cells (Figure 4E,F) was performed as follows. First, crosses between the two strains (kin1Δ and rad26Δ) were germinated and segregants were scored for the presence of kin1Δ or both kin1Δ and rad26Δ alleles. These strains were immediately grown in liquid media for one day and analyzed by brightfield microscopy. Two trials were performed, and 200 cells were scored per trial. Note: when the two strains (kin1Δ and kin1Δ rad26Δ) were propagated for longer than one day prior to cytological analysis, the percentage of round cells in kin1Δ cultures increased to the point where a difference between the morphologies of kin1Δ and kin1Δ rad26Δ strains ceased to exist (data not shown). We conclude that extended passage of the kin1Δ strain eventually results in a high percentage of round cells, regardless of the rad26Δ allele, and that it is critical to examine kin1Δ and kin1Δ rad26Δ phenotypes using young segregants. Therefore, we did not save the kin1Δ rad26Δ strain in our strain collection.

Thiamine repressed the expression of genes controlled by the nmt promoter [41]. Full expression from this promoter was achieved by growing cells in minimal medium (EMM)-thiamine, and expression was blocked by growing cells in EMM + 0.2 mM thiamine. To express nmt-atb2-gfp, a slightly repressible thiamine concentration of 0.2 μM was used [42].

The protocol to identify extracopy suppressors of rad26Δ TBZ-sensitivity follows (Figure 6A). TE257 (rad26Δ) was transformed with the Yamamoto cDNA library, in which cDNA expression is controlled by the nmt-promoter and marked with leu+. Original transformants were selected on EMM + thiamine - leucine media. Transformants were then replica-plated to EMM - thiamine - leucine media for 2 days in order to derepress nmt-driven cDNAs. Next, the transformants were replicated to EMM - thiamine - leucine + 10 μg/ml TBZ + 5 mg/L Phloxin B (vital dye; Fisher, Fair Lawn, NT) for 4 days. Twenty-two transformants were collected from these plates, and plasmids were isolated from each. Four of these plasmids reproducibly suppressed the sensitivity of rad26Δ cells on 20 μg/ml TBZ and were subcloned and sent to the sequencing core of the University of Colorado Health Science Center (sequencing revealed that we had isolated full length rad24+ cDNA). Each of these four plasmids was then transformed into nda2-KM52 (nda21; TE369) and mad2Δ (TW1219) strains to test for TBZ-suppression using the protocol described above.

To characterize the cytokinesis checkpoint (Figure 7C), the protocol of Mishra et al. (2005) was followed. Cultures of rad26Δ (TE257) and rad24Δ (TE465) cells were grown to an OD of 0.3, treated for 5 hours with 0.2 μM LatA, fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI. This experiment was repeated twice, and 200 cells were scored each time. Results of both experiments were similar, and data obtained from one of these experiments are shown.

Microscopy

To paraformaldehyde fix cells, a ~30% paraformaldehyde (Fisher, Fair Lawn, NJ) stock solution was made fresh, as described previously, and added to ~3% in yeast cultures for ten minutes [43]. For methanol fixation, cells expressing Atb2-GFP, Cenl-GFP or Rad26-GFP were suspended in cold methanol for one minute. Following either paraformaldehyde or methanol fixation, cells were washed twice in 100 μls SlowFade Component C (SlowFade Antifade Kit, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and air-dried on coverglass (Fisher). Once dried, 4.5 μls of SlowFade Component A was dropped on the coverglass that was then placed onto a slide. Achieving yeast monolayers that adhered tightly to the coverslips was critical for observing Cenl-GFP, Rad22-GFP and Rad26-GFP signals, none of which were affected by paraformaldehyde fixation (data not shown). To help ensure that such layers formed, coverglass was soaked in acetone for one day, scrubbed with dishwashing soap, wiped with 70% ethanol (Sigma) and air-dried prior to use. This protocol may remove a chemical film on the coverglass that prevents the formation of adherent monolayers (Robert West, personal communication).

To observe FITC-phalloidin, a previously described protocol was modified slightly [44]. Cells grown to an OD of 0.3 in a volume of 10 mls were fixed with paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, washed three times with PM buffer (5 mM K-phosphate, pH 7.0, 0.5 mM MgSO4) and suspended in PM buffer with 1% TritonX-100 (Sigma) for three minutes. Cells were then washed three times with PM buffer and resuspended in PEMBAL (100 mM PIPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4 pH 6.9, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% NaN3, 100 mM lysine hydrochloride). Next, 5 μls of stock FTTC-Phalloidin was added to the cells. After 1 hour at 26°C, cells were washed three times with 100 μls SlowFade Component C and resuspended in a small volume (~10 μls) of SlowFade Component A.

Two different microscopes and digital cameras were used to acquire images. Images in Figures 4 and 5 were acquired using a Nikon Optiphot equipped an RT-SPOT monochrome digital camera and SPOT software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Images of Figures 1 and 8 were acquired using a Leica DM5000 equipped with a Leica DFC350FX R2 digital camera, Leica FW4000 software and a motorized Z-axis. Cytoplasmic Rad26-GFP was observed after Leica image analysis software was used to reduce the background fluorescence of our best Z-stacks. Leica software was also used to measure the cell dimensions reported in Figure 3.

Authors' contributions

EB carried-out the experiments presented in Fig 2B; SV = Figs 1B, 2C, 7C; MH = Figs 1C, 8; KC = Figs 1A, 2A, 4EF; LE = Figs 4GHI, 5A–D; TW = Figs 2D, 3A–C, 4A–D, 6A–C, 7AB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We owe a great deal to Tamar Enoch for passing her stock collections on to TDW (thank you Tamar). We thank an anonymous NSF grant reviewer who candidly recommended that we pursue the TBZ phenotype of rad26Δ cells as opposed to other research questions. We thank anonymous BMC reviewers for very good critiques and suggestions. We thank Bob Weiss, Steve Harris, Sandy Berry-Lowe, Lisa Hines, Jim Mattoon and members of Dick Mclntosh's lab for suggestions that have been incorporated in this work. We thank Miguel Ferrerira for the rad22-gfp strain and Fred Chang for atb2-gfp. Technical contributions by Lance Russell (our Leica rep), Connie Pitman and Chuck Simmons are greatly appreciated. This work was supported by a UCHSC and American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant (57-001-47), and a National Science Foundation Major Research Initiative equipment grant (4540122).

Contributor Information

Erin E Baschal, Email: Erin.Baschal@UCHSC.edu.

Kuan J Chen, Email: kuan.chen@uchsc.edu.

Lee G Elliott, Email: lelliott@uccs.edu.

Matthew J Herring, Email: mherring@uccs.edu.

Shawn C Verde, Email: tyderium99@yahoo.com.

Tom D Wolkow, Email: twolkow@uccs.edu.

References

- Carr AM. DNA structure dependent checkpoints as regulators of DNA repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:983–994. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Adda di Fagagna F, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, Fiegler H, Carr P, Von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Carter NP, Jackson SP. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. Initiating cellular stress responses. Cell. 2004;118:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley NJ, Holtzman DA, Flaggs G, Keegan KS, DeMaggio A, Ford JC, Hoekstra M, Carr AM. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad3 checkpoint gene. EMBO J. 1996;15:6641–6651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RJ, Bentley NJ, Carr AM. A Rad3-Rad26 complex responds to DNA damage independently of other checkpoint proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:393–398. doi: 10.1038/15623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkow TD, Enoch T. Fission yeast Rad26 is a regulatory subunit of the Rad3 checkpoint kinase. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:480–492. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-03-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez D, Guntuku S, Qin J, Elledge SJ. ATR and ATRIP: partners in checkpoint signaling. Science. 2001;294:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1065521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse J, Jackson SP. LCD1: an essential gene involved in checkpoint control and regulation of the MEC1 signalling pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2000;19:5801–5812. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paciotti V, Clerici M, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The checkpoint protein Ddc2, functionally related to S. pombe Rad26, interacts with Mecl and is regulated by Mecl-dependent phosphorylation in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2046–2059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama T, Kondo T, Ando S, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K. Piel, a protein interacting with Mecl, controls cell growth and checkpoint responses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:755–764. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.755-764.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A, Kim SM, Dunphy WG. Claspin and the activated form of ATR-ATRIP collaborate in the activation of Chkl. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49599–49608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza CP, Ye XS, Osmani SA. Checkpoint defects leading to premature mitosis also cause endoreplication of DNA in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3661–3674. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya K, Carr AM. DNA checkpoints in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3847–3848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du LL, Nakamura TM, Moser BA, Russell P. Retention but not recruitment of Crb2 at double-strand breaks requires Radl and Rad3 complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6150–6158. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6150-6158.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SL, Portoso M, Mata J, Bahler J, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Methylation of histone H4 lysine 20 controls recruitment of Crb2 to sites of DNA damage. Cell. 2004;119:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka Y, Esashi F, Matsusaka T, Mochida S, Yanagida M. Damage and replication checkpoint control in fission yeast is ensured by interactions of Crb2, a protein with BRCT motif, with Cut5 and Chkl. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3387–3400. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrilla-Castellar ER, Arlander SJ, Karnitz L. Dial 9-1-1 for DNA damage: the Rad9-Husl-Radl (9-1-1) clamp complex. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo J, Toczyski D. A unified view of the DNA-damage checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:237–245. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury JM, Jackson SP. The complex matter of DNA double-strand break detection. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:40–44. doi: 10.1042/bst0310040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo JA, Cohen J, Toczyski DP. Two checkpoint complexes are independently recruited to sites of DNA damage in vivo. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2809–2821. doi: 10.1101/gad.903501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister P, Poidevin M, Francesconi S, Tratner I, Zarzov P, Baldacci G. Nuclear factories for signalling and repairing DNA double strand breaks in living fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5064–5073. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkow TD, Enoch T. Fission yeast Rad26 responds to DNA damage independently of Rad3. BMC Genet. 2003;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg KA, Michelson RJ, Putnam CW, Weinert TA. Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:617–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.060402.113540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyen Y, Zgheib O, Ditullio RAJ, Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Petty TJ, Sheston EA, Mellert HS, Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD. Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2004;432:406–411. doi: 10.1038/nature03114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind N, Russell P. Chkl and Cdsl: linchpins of the DNA damage and replication checkpoint pathways. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3889–3896. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.22.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baber-Furnari BA, Rhind N, Boddy MN, Shanahan P, Lopez-Girona A, Russell P. Regulation of mitotic inhibitor Mikl helps to enforce the DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1–11. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen PU, Bentley NJ, Martinho RG, Nielsen O, Carr AM. Mikl levels accumulate in S phase and may mediate an intrinsic link between S phase and mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2579–2584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Girona A, Kanoh J, Russell P. Nuclear exclusion of Cdc25 is not required for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 2001;11:50–54. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari B, Blasina A, Boddy MN, McGowan CH, Russell P. Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cdsl and Chkl. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:833–845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Forbes KC, Wu Z, Moreno S, Piwnica-Worms H, Enoch T. Replication checkpoint requires phosphorylation of the phosphatase Cdc25 by Cdsl or Chkl. Nature. 1998;395:507–510. doi: 10.1038/26766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng CY, Graves PR, Thoma RS, Wu Z, Shaw AS, Piwnica-Worms H. Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science. 1997;277:1501–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaway S, Liu HY, Walworth NC. Interaction of 14-3-3 protein with Chkl affects localization and checkpoint function. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:39–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JC, al-Khodairy F, Fotou E, Sheldrick KS, Griffiths DJ, Carr AM. 14-3-3 protein homologs required for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Science. 1994;265:533–535. doi: 10.1126/science.8036497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Murray AW. Feedback control of mitosis in budding yeast. Cell. 1991;66:519–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber PM, Rine J. Overlapping roles of the spindle assembly and DNA damage checkpoints in the cell-cycle response to altered chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2002;161:521–534. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collura A, Blaisonneau J, Baldacci G, Francesconi S. The fission yeast Crb2/Chkl pathway coordinates the DNA damage and spindle checkpoint in response to replication stress induced by topoisomerase I inhibitor. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7889–7899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7889-7899.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto I, Murakami H, Tonami Y, Moriyama A, Nakanishi M. DNA replication checkpoint control mediated by the spindle checkpoint protein Mad2p in fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47372–47378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno SA, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. In: Fink CGaGR, editor. Methods in Enzymology: Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. New York: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maundrell K. Thiamine-repressible expression vectors pREP and pRIP for fission yeast. Gene. 1993;123:127–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90551-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding DQ, Chikashige Y, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Oscillatory nuclear movement in fission yeast meiotic prophase is driven by astral microtubules, as revealed by continuous observation of chromosomes and microtubules in living cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:701–712. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris JP, Blobel G. Identification and characterization of a yeast nucleolar protein that is similar to a rat liver nucleolar protein. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:17–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay MK, Tabor CW, Tabor H. Absolute requirement of spermidine for growth and cell cycle progression of fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10330–10334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162362899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs CW, Adams AE, Szaniszlo PJ, Pringle JR. Functions of microtubules in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1409–1426. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann K, Lorentz A, Schmidt H. The fission yeast rad22 gene, having a function in mating-type switching and repair of DNA damages, encodes a protein homolog to Rad52 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5940–5944. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S, Watson A, Sheedy DM, Martin B, Carr AM. Gross chromosomal rearrangements and elevated recombination at an inducible site-specific replication fork barrier. Cell. 2005;121:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner AD, Murray AW. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:773–780. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantes PA. Epistatic gene interactions in the control of division in fission yeast. Nature. 1979;279:428–430. doi: 10.1038/279428a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill DP, Hyams JS. Cytokinetic actomyosin ring formation and septation in fission yeast are dependent on the full recruitment of the polo-like kinase Plol to the spindle pole body and a functional spindle assembly checkpoint. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3575–3586. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javerzat JP, Cranston G, Allshire RC. Fission yeast genes which disrupt mitotic chromosome segregation when overexpressed. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4676–4683. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima K, Nakagawa T, Straight AF, Murray A, Chikashige Y, Yamashita YM, Hiraoka Y, Yanagida M. Dynamics of centromeres during metaphase-anaphase transition in fission yeast: Disl is implicated in force balance in metaphase bipolar spindle. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3211–3225. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayles J, Nurse P. A journey into space. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:647–656. doi: 10.1038/35089520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DE, Bishop JM. A putative protein kinase gene (kinl+) is important for growth polarity in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8272–8276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Carbona S, Allix C, Philippe M, Le Goff X. The protein kinase kinl is required for cellular symmetry in fission yeast. Biol Cell. 2004;96:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewes G, Nurse P. The protein kinase kinl, the fission yeast orthologue of mammalian MARK/PAR-1, localises to new cell ends after mitosis and is important for bipolar growth. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:45–49. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Khodairy F, Fotou E, Sheldrick KS, Griffiths DJ, Lehmann AR, Carr AM. Identification and characterization of new elements involved in checkpoint and feedback controls in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:147–160. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SG, Chang F. New end take off: regulating cell polarity during the fission yeast cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1046–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J, Hagan IM, Hyams JS. Growth polarity and cytokinesis in fission yeast: the role of the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1986;5:229–241. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1986.supplement_5.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham RJJ, Chang F. Role of actin polymerization and actin cables in actin-patch movement in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:235–244. doi: 10.1038/35060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verde F. Cell polarity: a tale of two Ts. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R600–2. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T, Umesono K, Hirata A, Yanagida M. Cold-sensitive nuclear division arrest mutants of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Mol Biol. 1983;168:251–270. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T, Adachi Y, Hiraoka Y, Yanagida M. Identification of the pleiotropic cell division cycle gene NDA2 as one of two different alpha-tubulin genes in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cell. 1984;37:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang H, Balasubramanian MK. A checkpoint that monitors cytokinesis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1223–1230. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.7.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra M, Karagiannis J, Sevugan M, Singh P, Balasubramanian MK. The 14-3-3 protein rad24p modulates function of the cdc14p family phosphatase clplp/flplp in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1376–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Subramanian RR, Masters SC. 14-3-3 proteins: structure, function, and regulation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:617–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung K, Datta A, Kolodner RD. Suppression of spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements by S phase checkpoint functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2001;104:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS, Enoch T, Leder P. Inactivation of mouse Husl results in genomic instability and impaired responses to genotoxic stress. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1886–1898. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuljis RO, Chen G, Lee EY, Aguila MC, Xu Y. ATM immunolocalization in mouse neuronal endosomes: implications for ataxia-telangiectasia. Brain Res. 1999;842:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow C, Ribaut-Barassin C, Zwingman TA, Pope AJ, Brown KD, Owens JW, Larson D, Harrington EA, Haeberle AM, Mariani J, Eckhaus M, Herrup K, Bailly Y, Wynshaw-Boris A. ATM is a cytoplasmic protein in mouse brain required to prevent lysosomal accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:871–876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun HH, Gatti RA. Ataxia-telangiectasia, an evolving phenotype. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Peng C, Luff J, Spring K, Watters D, Bottle S, Furuya S, Lavin MF. Oxidative stress is responsible for deficient survival and dendritogenesis in purkinje neurons from ataxia-telangiectasia mutated mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11453–11460. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11453.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters D, Kedar P, Spring K, Bjorkman J, Chen P, Gatei M, Birrell G, Garrone B, Srinivasa P, Crane DI, Lavin MF. Localization of a portion of extranuclear ATM to peroxisomes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34277–34282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog KH, Chong MJ, Kapsetaki M, Morgan JI, McKinnon PJ. Requirement for Atm in ionizing radiation-induced cell death in the developing central nervous system. Science. 1998;280:1089–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon PJ. ATM and ataxia telangiectasia. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:772–776. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZH, Shi Y, Tibbetts RS, Miyamoto S. Molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-kappaB signaling in response to genotoxic stimuli. Science. 2006;311:1141–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1121513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling DL, Yingling J, Wynshaw-Boris A. Role of 14-3-3 proteins in eukaryotic signaling and development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;68:281–315. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)68010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozuelo Rubio M, Geraghty KM, Wong BH, Wood NT, Campbell DG, Morrice N, Mackintosh C. 14-3-3-affinity purification of over 200 human phosphoproteins reveals new links to regulation of cellular metabolism, proliferation and trafficking. Biochem J. 2004;379:395–408. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus PR, Hofmann AF, Harris SD. Characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans 14-3-3 homologue, ArtA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;210:61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavazi I, Semighini CP, Kress MR, Harris SD, Goldman GH. Regulation of hyphal morphogenesis and the DNA damage response by the Aspergillus nidulans ATM homologue, AtmA. Genetics. 2006 doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon PJ, Burgoyne LA. Altered cellular morphology and microfilament array in ataxia-telangiectasia fibroblasts. Eur J Cell Biol. 1985;39:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton DA, Olsten ME, Kim K, Doherty-Kirby A, Lajoie G, Cooper JA, Litchfield DW. The pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein CKIP-1 is involved in regulation of cell morphology and the actin cytoskeleton and interaction with actin capping protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3519–3534. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3519-3534.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisan T, Cortes-Bratti X, Chaves-Olarte E, Stenerlow B, Thelestam M. The Haemophilus ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin induces DNA double-strand breaks and promotes ATM-dependent activation of RhoA. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:695–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TM, Moser BA, Russell P. Telomere binding of checkpoint sensor and DNA repair proteins contributes to maintenance of functional fission yeast telomeres. Genetics. 2002;161:1437–1452. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura A, Naito T, Ishikawa F. Genetic control of telomere integrity in Schizosaccharomyces pombe: rad3(+) and tell(+) are parts of two regulatory networks independent of the downstream protein kinases chkl(+) and cdsl(+) Genetics. 1999;152:1501–1512. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard P, Maure JF, Partridge JF, Genier S, Javerzat JP, Allshire RC. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science. 2001;294:2539–2542. doi: 10.1126/science.1064027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Nirantar S, Crasta K, Cheng AY, Surana U. DNA replication checkpoint prevents precocious chromosome segregation by regulating spindle behavior. Mol Cell. 2004;16:687–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachet Y, Tournier S, Millar JB, Hyams JS. Mechanism controlling perpendicular alignment of the spindle to the axis of cell division in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2004;23:1289–1300. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal M, Bloom K. Control of spindle polarity and orientation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:160–166. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01954-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Daga RR, Chang F. Intra-nuclear microtubules and a mitotic spindle orientation checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1245–1246. doi: 10.1038/ncb1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]