Abstract

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that persistently colonizes more than half of the global human population. In order to successfully colonize the human stomach, H. pylori must initially overcome multiple innate host defenses. Remarkably, H. pylori can persistently colonize the stomach for decades or an entire lifetime despite development of an acquired immune response. This review focuses on the immune response to H. pylori and the mechanisms by which H. pylori resists immune clearance. Three main sections of the review are devoted to (i) analysis of the immune response to H. pylori in humans, (ii) analysis of interactions of H. pylori with host immune defenses in animal models, and (iii) interactions of H. pylori with immune cells in vitro. The topics addressed in this review are important for understanding how H. pylori resists immune clearance and also are relevant for understanding the pathogenesis of diseases caused by H. pylori (peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric lymphoma).

INTRODUCTION

The gram-negative bacterium Helicobacter pylori persistently colonizes the human stomach (34, 145, 153, 217). H. pylori colonization of the stomach elicits humoral and cellular immune responses (28, 52, 129, 180), which in most cases do not result in bacterial clearance. In the absence of antibiotic therapy, H. pylori can persist in the human stomach for decades or for an entire lifetime (116). H. pylori is widespread throughout the world and is present in about 50% of the global human population (178, 226). H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation does not cause symptoms in most infected persons (56) but is associated with an increased risk for development of duodenal ulcer disease, gastric ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric lymphoma (45, 179, 183, 217, 233). In this review, we examine innate and adaptive immune responses to H. pylori and discuss mechanisms by which H. pylori evades immune clearance.

ANTIBACTERIAL PROPERTIES OF THE HUMAN STOMACH

Humans ingest many microorganisms each day, but most cannot successfully colonize the stomach. One of the most important antibacterial properties of the human stomach is its acidic pH. Under fasting conditions, the human gastric luminal pH is <2, which prevents the proliferation of bacteria within the gastric lumen. Within the gastric mucus layer overlying gastric epithelial cells, a pH gradient exists, ranging from a pH of about 2 at the luminal surface to a pH of between 5 and 6 at the epithelial cell surface (185, 225). After entering the stomach, H. pylori penetrates the gastric mucus layer (203) and thereby encounters a less acidic environment than that which is present within the gastric lumen. H. pylori typically does not traverse the epithelial barrier (97), and it is classified as a noninvasive bacterial organism. Within the gastric mucus layer, most H. pylori organisms are free living, but some organisms attach to the apical surface of gastric epithelial cells and may occasionally be internalized by these cells (10, 97, 119, 173).

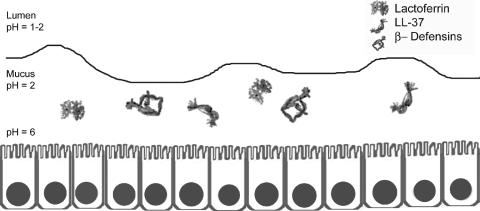

Multiple factors produced by the gastric mucosa limit the proliferation of bacteria (Fig. 1). Antibacterial peptides, including β-defensins 1 and 2 and LL-37, are active against many different species of bacteria (74, 94). Lactoferrin inhibits bacterial growth by restricting the availability of extracellular Fe3+ (133) and can have direct effects on bacterial membrane permeability (13, 175, 253). Lactoferricin, a peptide derived from lactoferrin, also has antimicrobial properties (80). Lysozyme can degrade the peptidoglycan of many bacterial species. Surfactant protein D is capable of aggregating many different types of microorganisms in a calcium-dependent and lectin-specific manner (114, 158, 164). Finally, specific components of human gastric mucin can inhibit bacterial growth; alpha-1,4-GluNAC-capped O-glycans inhibit biosynthesis of cholesteryl-α-d-glucopyranoside, a component of the H. pylori cell wall (112).

FIG. 1.

Antibacterial properties of the stomach. The stomach is intrinsically resistant to bacterial colonization. Factors which contribute to this resistance include gastric acidity, lactoferrin, and antibacterial peptides (LL-37, β-defensin 1, and β-defensin 2). The gastric epithelial layer constitutes a physical barrier that prevents entry of bacteria into the gastric mucosa. Ribbon diagrams of lactoferrin, β-defensins, and LL-37 are derived from published structures (24, 200, 218).

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are present on the surface of gastric epithelial cells and can recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (21, 201, 216). If bacteria invade and penetrate the gastric epithelial barrier, the alternate pathway of complement is activated, and invading bacteria encounter macrophages and neutrophils. Since most H. pylori organisms localize within the gastric mucus layer and do not invade gastric tissue, contact between H. pylori and phagocytic cells probably occurs infrequently unless there are disruptions in the gastric epithelial barrier.

The antibacterial properties of the human stomach described above prevent most bacterial species from colonizing the stomach. Based on the high prevalence of H. pylori in humans throughout the world, it may be presumed that H. pylori possesses mechanisms to overcome these innate host defenses.

H. PYLORI FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO GASTRIC COLONIZATION

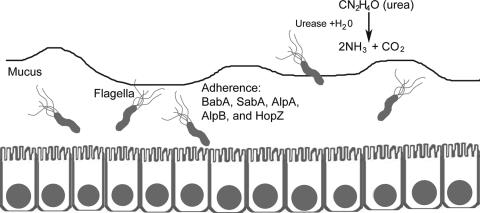

The capacity of H. pylori to colonize the human stomach can be attributed to the production of specific bacterial products (Fig. 2). Numerous H. pylori components have been designated colonization factors based on the demonstration that null mutant strains defective in the production of these factors are impaired in the ability to colonize the stomach in animal models. For example, H. pylori null mutant strains defective in production of urease or flagella are unable to colonize animal models (59, 62). Urease hydrolyzes urea to yield ammonium ions and thereby contributes to the acid resistance of H. pylori (144). Flagella confer the property of motility and enable H. pylori to penetrate the gastric mucus layer. In a recent signature-tagged mutagenesis analysis, 47 H. pylori genes were found to be essential for colonization of the Mongolian gerbil stomach but not essential for growth of H. pylori in vitro (111). Probably many other H. pylori factors are also required for colonization of the stomach.

FIG. 2.

Colonization factors of H. pylori. Multiple bacterial factors contribute to the ability of H. pylori to colonize the stomach. Urease contributes to the acid resistance of H. pylori. Flagella permit bacterial motility, which allows bacterial penetration of the mucus layer. Several outer membrane proteins, including BabA, SabA, AlpA, AlpB, and HopZ, can mediate bacterial adherence to gastric epithelial cells.

Multiple H. pylori outer membrane proteins, including BabA, SabA, AlpA, AlpB, and HopZ, can mediate H. pylori adherence to gastric epithelial cells (Fig. 2). Attachment of H. pylori to gastric epithelial cells results in activation of numerous signaling pathways (87) and permits efficient delivery of toxins or other effector molecules into the cells. Studies in an animal model indicate that attachment of H. pylori to epithelial cells influences the development of gastric mucosal inflammation, production of autoantibodies, and parietal cell loss (90).

H. pylori outer membrane proteins and other surface components are likely targets for recognition by host immune defenses. One mechanism by which H. pylori evades immune recognition may involve a form of antigenic disguise in which the bacteria are coated with host proteins. For example, H. pylori PgbA and PgbB proteins bind plasminogen, and the bacteria can thereby be coated with this host protein (108). Other mechanisms for evading immune recognition may involve phase variation and antigenic variation of surface components. Phase variation has been reported for multiple H. pylori surface components, including outer membrane proteins and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antigens (14, 198, 210, 241). Genetic rearrangements contribute to antigenic variation in CagY (16), and intragenomic recombination may contribute to antigenic variation in outer membrane proteins (210).

LPS from most bacterial organisms serves as a potent signal for development of an inflammatory response. An important H. pylori adaptation is the synthesis of LPS that is less proinflammatory than LPSs from many other gram-negative species (114, 157, 181). In comparison to LPS from Escherichia coli or Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, H. pylori LPS has approximately 500-fold-lower endotoxic activity (162), and its ability to stimulate macrophage production of proinflammatory cytokines, nitric oxide, and prostaglandins is relatively weak (35, 181). The low biological activity of H. pylori LPS is attributable to modifications of its lipid A component (157, 162). H. pylori strains commonly express LPS O antigens that are structurally related to Lewis blood group antigens found on human cells (19, 154). This similarity in structure between H. pylori LPS and Lewis blood group antigens may represent a form of molecular mimicry or immune tolerance that permits H. pylori LPS antigens to be shielded from immune recognition because of similarity to “self” antigens.

Many H. pylori strains contain a 40-kb region of chromosomal DNA known as the cag pathogenicity island (PAI) (5, 40). Some strains contain an incomplete cag PAI (less than 40 kb in size), and in other strains the cag PAI is completely absent (40, 166). One product of the cag pathogenicity island, CagA, is translocated into gastric epithelial cells and induces numerous alterations in cellular signaling (18, 98, 171, 204, 214). Multiple other products of the cag pathogenicity island have a role in secretion of CagA and in altering gene transcription in gastric epithelial cells (5, 40, 71, 87, 205). In comparison to cag PAI-negative H. pylori strains, cag PAI-positive strains stimulate gastric epithelial cells to produce high levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-8 (IL-8) (5, 38, 71, 87, 125, 161, 205). Gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease occur more commonly in persons infected with cag PAI-positive strains (particularly those strains containing an intact 40-kb cag PAI) than in persons infected with cag PAI-negative strains (33, 70, 166, 236).

Several H. pylori factors are known to interact directly with immune cells and modulate immune responses to H. pylori. These factors include a secreted toxin (VacA) (37, 46, 77, 219), neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP or NapA) (68, 197), arginase (83, 256), urease (93, 139, 140), Hsp60 (a GroEL heat shock protein) (81), SabA (235), HcpA (53), CagA (170, 234), and a proinflammatory peptide designated Hp(2-20) (29). Several of these factors act on multiple different types of immune cells. For example, VacA alters the function of T lymphocytes, B cells, macrophages, and mast cells (37, 49, 77, 152, 219, 220, 258), and HP-NAP acts on neutrophils, mast cells, and monocytes (155, 156, 197). The activities of H. pylori factors that interact directly with immune cells will be discussed in greater detail below.

IMMUNE RESPONSE TO H. PYLORI IN HUMANS

Acute Infection

There have been several reports of acute H. pylori infection in humans, and these provide insight into the immune responses to H. pylori that occur within the first few days after infection. Soon after the discovery of H. pylori, two volunteers ingested cultures of the organism (143, 159, 160). Both volunteers developed nausea, vomiting, or fever within 10 days after ingesting H. pylori, and gastric biopsies revealed mucosal inflammation in both volunteers. By 2 weeks postinfection, a sharp rise in the gastric pH to about 7 was detected in one of the volunteers. In 1979, a group of 17 volunteers were probably inadvertently infected with H. pylori (85, 191), and these persons also developed hypochlorhydria in association with gastric mucosal inflammation. Further insight comes from a case in which an endoscopist reported a syndrome of cramping epigastric pain, accompanied by transient fasting achlorhydria and acute neutrophilic gastritis, about 5 days after infection with H. pylori (208). Within 14 days after infection, this individual developed an H. pylori-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgA immune response.

More recently, 20 human volunteers were experimentally infected with 104 to 1010 CFU of an H. pylori strain (86). Symptoms occurred most frequently during the second week after infection and included dyspepsia (in >50% of subjects), headaches, anorexia, abdominal pain, belching, and halitosis. Gastric biopsies performed 2 weeks after infection showed infiltration of lymphocytes and monocytes, along with significantly increased expression of IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-6 in the gastric antrum (86). Four weeks after infection, the numbers of gastric CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were increased compared to preinfection levels, indicating the development of an early adaptive immune response (168). These cases provide evidence that gastric inflammation develops within a short period of time after H. pylori infection and that the initial colonization of the stomach by H. pylori frequently results in upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Either innate immune responses to H. pylori or early adaptive immune responses could account for the gastric mucosal inflammatory responses and symptoms that accompany acute infection.

Chronic Infection

Gastric mucosal biopsies from humans who are persistently infected with H. pylori reveal an increased concentration of various types of leukocytes compared to biopsies from uninfected humans (45, 55). This inflammatory response to H. pylori has been termed “chronic superficial gastritis” (55, 243). Lymphocytes (both T cells and B cells), macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) are usually present (27, 55, 222). CD4+ T cells are typically more abundant than CD8+ T cells (22, 132, 146, 184). CD4+/CD25hi regulatory T cells expressing FOXP3 are present in higher numbers in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori-infected persons than in uninfected persons, and these are presumed to play an important role in regulating the inflammatory response (130, 131). Various cell types, including B cells and CD4+ cells, sometimes organize into lymphoid follicles (228). The chronic gastric mucosal inflammatory response to H. pylori probably reflects the combined effects of a cellular immune response and an ongoing stimulation of an innate immune response.

In contrast to the intestine, the stomach does not contain Peyer's patches or M cells (165). Therefore, there is some uncertainty about the location where priming of the immune response to H. pylori occurs. Gastric epithelial cells up-regulate expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and costimulatory molecules during H. pylori infection (17, 255), and potentially these cells have a role in antigen presentation. Monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells in the lamina propria of the gastric mucosa also may play important roles in antigen presentation (115, 222, 240). Alternatively, priming of the immune response to H. pylori may occur within lymph nodes draining the stomach or may occur at intestinal sites in response to H. pylori antigens or intact organisms that are shed from the stomach.

H. pylori-specific CD4+ T cells are detectable in the gastric mucosae of H. pylori-infected persons but not uninfected persons (52, 54, 132). One study reported that about 15% of CD4+ T-cell clones isolated from the stomachs of H. pylori-infected persons were H. pylori specific, whereas the other T-cell clones did not proliferate in response to antigens in H. pylori lysate (52). Some T-cell clones from H. pylori-infected patients recognize epitopes on parietal cell H+,K+-ATPase (9), and it has been suggested that recognition of H+,K+-ATPase by gastric T cells may contribute to the development of autoimmune gastritis (51).

Levels of numerous cytokines, including gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-18, are increased in the stomachs of H. pylori-infected humans compared to uninfected humans (47, 126). IL-4 has not been detected in the gastric mucosae of most H. pylori-infected persons (110, 126, 184). The Th1-defining cytokine, IFN-γ, is expressed by a higher proportion of gastric T cells from H. pylori-infected persons than gastric T cells from uninfected persons (22, 91, 110, 126, 211). In one study, 83% of H. pylori-specific gastric T-cell clones produced IFN-γ but not IL-4 upon stimulation with H. pylori antigens, compared to 17% of clones that produced IL-4 (22, 52). Based on the relative abundance of IFN-γ-producing T cells and the relative scarcity of IL-4-producing gastric T cells in the setting of H. pylori infection, it has been concluded that H. pylori infection leads to a Th1-polarized response (22, 211). In the setting of H. pylori infection, multiple cytokines in the gastric mucosa (including TNF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-18) are predicted to have proinflammatory effects, whereas IL-10 is an immunoregulatory cytokine that may limit the inflammatory response.

A humoral immune response to H. pylori is elicited in nearly all H. pylori-infected humans (180). In a study of H. pylori-infected human volunteers, H. pylori-specific serum IgM antibodies were present by 4 weeks postinfection (168). Serum IgA and IgG antibodies in persons with chronic H. pylori infection are directed toward many different H. pylori antigens (147, 180). Antibody-secreting cells producing H. pylori-specific IgA or IgM antibodies are detectable in the gastric mucosae of H. pylori-infected persons (147), and secretory IgA antibodies to H. pylori are detectable in gastric juice, which suggests that H. pylori infection elicits a local secretory IgA response in the stomach (96, 147).

Factors Modulating the Immune Response to H. pylori in Humans

The gastric mucosal inflammatory response to H. pylori in humans may be modulated by characteristics of the H. pylori strain. Infection with H. pylori strains containing the cag PAI is typically associated with a more severe inflammatory response than that which accompanies infection with cag PAI-negative strains (33, 230). Similarly, H. pylori strains containing type s1/m1 vacA alleles, containing a gene of unknown function known as jhp0917/0918 (dupA), and expressing certain outer membrane proteins (BabA and HopH [OipA]) are associated with an enhanced inflammatory response (128, 137, 186, 252).

The gastric inflammatory response to H. pylori also may be modulated by characteristics of the human host. H. pylori-associated gastric inflammation in adults is characterized by infiltration of mononuclear cells and neutrophils, whereas in children the inflammatory response often is predominantly lymphocytic with relatively few neutrophils (246). Adults who are persistently colonized with H. pylori for many decades may develop atrophic gastritis (an inflammatory process characterized by loss of glandular structures and parietal cells in the gastric mucosa), which is considered a preneoplastic lesion (45, 117).

No immunodeficiency diseases are known to result in enhanced severity of H. pylori-associated inflammation. For example, gastric inflammation is not more severe in H. pylori-infected humans with IgA deficiency than in immunocompetent hosts (36). However, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in several genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines can influence the clinical outcome of H. pylori infection (Table 1). Polymorphisms that result in elevated levels of IL-1β and TNF-α and reduced levels of IL-10 have been associated with an increased risk of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer (64, 66, 101, 134, 232, 248). A polymorphism in the promoter region of IL-1 receptor antagonist that leads to reduced expression of IL-1 receptor antagonist has also been associated with an increased incidence of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer (64, 135, 187). The exact mechanisms by which these polymorphisms affect the risk for gastric cancer are not yet completely understood. Some of the TNF-α and IL-10 polymorphisms associated with increased risk for gastric cancer are considered proinflammatory genotypes (66, 134), and IL-1β is known to be a potent inhibitor of gastric acid secretion (254). These polymorphisms may predispose individuals to develop gastric atrophy and gastric cancer by pathways involving enhancement in the severity of gastric inflammation and a reduction in gastric acid secretion (254).

TABLE 1.

Genetic polymorphisms in cytokine-encoding genes which influence the clinical course of H. pylori infection in humans

| Gene product | Polymorphism(s) | Postulated effect of polymorphism | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | IL-1B-31C, IL-1B-511T | Increased expression of IL-1β, which induces expression of proinflammatory cytokines and inhibits acid secretion | 63-66, 134, 135 |

| IL-1RA | IL-1RN*2 | Reduced expression of IL-1 receptor agonist, which increases IL-1β activity | 135 |

| IL-2 | IL-2-330T | Reduced IL-2 expression | 232 |

| IL-10 | IL-10 haplotype ATA | Reduced expression of IL-10, which increases proinflammatory cytokine activity | 66 |

| TNF | TNF-A-308A | Increased TNF expression, which induces expression of proinflammatory cytokines and inhibits acid secretion | 66, 134 |

Although H. pylori is very successful in evading immune clearance, it is possible that the immune response is sometimes successful in clearing H. pylori from the stomach. The frequency with which H. pylori is cleared by the immune response is not known. In regions of the world with a high incidence of H. pylori infection, reinfection occurs commonly following H. pylori eradication (213), which suggests that a protective immune response develops infrequently in H. pylori-infected persons.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN H. PYLORI AND HOST DEFENSES IN ANIMAL MODELS

H. pylori Infection of Wild-Type Animals

Several animal models of H. pylori infection have been developed, utilizing mice, Mongolian gerbils, guinea pigs, rats, ferrets, beagle dogs, cats, gnotobiotic piglets, or nonhuman primates (reviewed in references 174 and 245). The use of nonhuman primate models is of particular interest because of the close relatedness of these animals to humans. The rhesus monkey can be experimentally infected with H. pylori, and a large proportion of monkeys in certain colonies are naturally infected with H. pylori (57, 58, 148, 209). Histopathological changes that occur in the gastric mucosae of monkeys in response to H. pylori infection are similar to the changes that occur in H. pylori-infected humans (148). However, H. pylori-associated peptic ulceration and gastric adenocarcinoma have not been described in nonhuman primate models (148).

Mongolian gerbils can be experimentally infected with H. pylori and develop gastric inflammation characterized by infiltration of mononuclear cells and neutrophils (149, 172, 247). An attractive feature of the Mongolian gerbil model is that these animals may develop gastric mucosal ulceration or gastric adenocarcinoma in response to H. pylori infection (73, 100, 172, 244), and they thus provide a model for two important H. pylori-associated diseases that occur in humans. Several studies suggest that products of the H. pylori cag pathogenicity island contribute to gastric pathology in the gerbil model (105, 172, 192). Limitations of this model include the relative paucity of gerbil-specific immunologic reagents and the fact that Mongolian gerbils are outbred.

The mouse model is frequently utilized because of low cost, availability of relevant reagents, and the potential for development of knockout mice (142). H. pylori can persistently colonize the stomachs of wild-type mice for periods of at least 15 months. However, wild-type mice do not develop gastric mucosal ulceration or gastric adenocarcinoma in response to H. pylori. One limitation of the mouse model is that only a few human isolates of H. pylori have been successfully adapted to permit efficient colonization of the mouse stomach (20). Infant mice and certain types of knockout mice (e.g., IL-12 knockout mice) seem to be more permissive hosts than are wild-type adult mice and tolerate infection with a broader range of H. pylori strains (89, 99). A different Helicobacter species, H. felis, also can colonize conventional inbred mice and causes more severe gastric inflammation than does H. pylori (196). However, H. felis does not express several important H. pylori virulence factors (249).

The gastric mucosal inflammation that develops in wild-type mice infected with H. pylori consists primarily of lymphocytes and other mononuclear cells. Most of the infiltrating cells are CD4+ T cells, but CD8+ T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and monocytes are also present (167, 199, 207, 237). The intensity of inflammation that develops in H. pylori-infected mice is relatively mild compared to that which develops in H. pylori-infected humans and is also relatively mild compared to that which develops in H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils (121). Neutrophils are typically present in the gastric mucosae of H. pylori-infected humans (194, 246) and gerbils (100) but are less commonly observed in the gastric mucosae of H. pylori-infected mice (138).

C57BL/6 mice have been commonly used for studies of H. pylori. Gastric levels of IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF, and IL-6 are increased in H. pylori-infected C57BL/6 mice compared to uninfected mice, whereas gastric levels of IL-4 are not increased in response to H. pylori infection (150, 212). Upon antigen stimulation ex vivo, splenocytes from H. pylori-infected C57BL/6 mice produce substantially more IFN-γ than IL-4 (107, 127, 207). These patterns of cytokine expression are indicative of a predominantly Th1 response, which is similar to the response which occurs in H. pylori-infected humans.

There is variability among different strains of inbred mice in susceptibility to H. pylori infection (138, 231) and in host responses to H. pylori. Inbred mice are known to have default T-helper responses, and therefore, the genetic backgrounds of inbred mice may influence the T-cell response to H. pylori. C57BL/6 mice have a default Th1 response, whereas BALB/c mice have a default Th2 response (113). This difference may be a factor that helps to explain why BALB/c mice are relatively resistant to H. pylori colonization and why H. pylori-infected BALB/c mice develop relatively mild gastric inflammation compared to H. pylori-infected C57BL/6 mice (109, 196).

H. pylori Infection of Knockout Mice

Mouse knockout models have served as valuable tools for investigating the roles of various components of the immune response to H. pylori. Features of H. pylori infection in selected mouse knockout models are discussed below, and a summary of the data is shown in Table 2. As noted above, inbred mice are known to have default T-helper responses, and consequently, the genetic backgrounds of mouse strains can potentially influence the results of knockout mouse studies. Most studies of H. pylori infection in knockout mice have been performed with C57BL/6 animals, which have a default Th1 response.

TABLE 2.

H. pylori infection of mouse knockout modelsa

| Knockout model (mouse strain[s]) | H. pylori strain | Bacterial density compared to WT | Inflammation compared to control | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOS2−/− (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Similar colonization | More severe gastritis | 32 |

| Gp91phox/NOS2−/− (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Reduced colonization | More severe gastritis | 32 |

| SCID (B- and T-cell deficient) (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Greater colonization | No gastric inflammation | 61 |

| μ-MT (B-cell deficient) (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Reduced colonization | More severe gastritis | 3 |

| MHC class I KO (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Greater colonization | ND | 177 |

| MHC class II KO (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Greater colonization | ND | 177 |

| IFN-γ KO (C57BL/6) | SM326 | ND | No gastric inflammation | 207 |

| IFN-γ KO (C57BL/6) | CPY2052 | Greater colonization | No gastric inflammation | 199,251 |

| IFN-γ KO (C57BL/6 and BALB/c) | SM326 | More frequent recovery of bacteria | ND | 109 |

| IRF-1 KO (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Greater colonization | No gastritis | 212 |

| IL-4 KO (C57BL/6) | SM326 | ND | More severe gastritis | 207 |

| IL-4 KO (C57BL/6 and BALB/c) | SM326 | Similar colonization | ND | 109 |

| IL-4 KO (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Similar colonization | Similar degree of gastritis | 42 |

| IL-4 Tg (IL-4 overexpression) (C3H) | SS1 | Similar colonization | Similar degree of gastritis | 42 |

| IL-10 KO (IL-10+/−, 129 × C57BL/6) | SS1 | Reduced colonization | More severe gastritis | 43 |

| IL-12 KO (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Similar colonization | Similar degree of gastritis | 2 |

| FasL KO (C57BL/6) | SS1 | Similar colonization | Similar degree of gastritis | 107 |

| TNF KO (C57BL/6) | CPY2052 and KP142 | Greater colonization | Similar degree of gastritis | 251 |

| TNF receptor KO (C57BL/6) | Six clinical isolates of H. pylori | ND | Similar degree of gastritis | 229 |

This table summarizes the results of selected studies in which transgenic mouse models were infected with Helicobacter pylori. WT, wild type; ND, not determined; KO, knockout.

SCID (severe combined immunodeficient) mice lack mature T and B lymphocytes due to a defective capacity to express rearranged antigen receptors and are therefore deficient in both humoral and cell-mediated immunity. SCID mice can be successfully colonized by H. pylori, but these mice develop minimal gastric inflammation in response to infection (61). This indicates that an adaptive immune response is required for development of chronic gastric inflammation in response to H. pylori and also indicates that gastric inflammation is not required in order for H. pylori to persistently colonize the stomach. If H. pylori-infected SCID mice receive splenocytes from uninfected C57BL/6 mice through adoptive transfer, the recipient SCID mice develop severe gastric inflammation characterized by a neutrophilic infiltrate (61). The gastritis that develops in H. pylori-infected SCID recipient mice is more severe than that which occurs in H. pylori-infected C57BL/6 mice (61). The transfer of splenocytes to SCID mice potentially induces a severe form of gastritis due to the absence of regulatory cells in the SCID mice (61, 182).

μ-MT (B-cell-deficient) mice infected with H. pylori develop gastritis that is more severe than that which occurs in wild-type mice, and subsequently H. pylori infection is cleared from the stomachs of the B-cell-deficient mice (3). There are several possible reasons why H. pylori-induced gastritis may be more severe in B-cell-deficient mice than in wild-type mice. For example, antibodies produced by wild-type mice may engage the inhibitory IgG receptor (FcγRIIb) on leukocytes and increase expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 (3).

In comparison to H. pylori-infected wild-type mice, H. pylori-infected mice with defects in IFN-γ expression (IFN-γ−/− mice or interferon response factor 1−/− mice) develop less severe gastric inflammation and have higher bacterial colonization densities (2, 169, 199, 207, 212, 251). This suggests that IFN-γ contributes to increased severity of H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation while also contributing to reducing bacterial colonization. In support of this view, H. pylori-infected SCID mice reconstituted with splenocytes that express IFN-γ developed more severe gastritis than did mice reconstituted with IFN-γ-deficient splenocytes (60). IFN-γ may indirectly modulate the severity of gastritis by activating macrophages to secrete proinflammatory cytokines and also may down-regulate the expression of anti-inflammatory factors such as the anti-inflammatory cytokine transforming growth factor β (215).

In comparison to Helicobacter-infected mice that express IL-10, infected IL-10−/− mice develop more severe gastritis (26, 43). IL-10 is known to be a potent anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokine, and therefore it seems likely that IL-10 has a role in down-regulating H. pylori-induced inflammation (43). One study reported that H. pylori-infected IL-4−/− mice developed more severe gastritis than did H. pylori-infected wild-type C57BL/6 mice (207). Similarly, H. felis-infected IL-4−/− mice developed significantly more severe gastric inflammation than did H. felis-infected IL-4+/+ mice (151). Although the results of studies analyzing IL-4−/− mice have not been entirely uniform (42, 109), these data suggest that both IL-10 and IL-4 have a role in down-regulating gastric inflammation (26, 72, 151, 207, 257).

A general theme that emerges from studies of H. pylori in mouse models is that there is a reciprocal relationship between the intensity of gastric mucosal inflammation and bacterial load (or colonization density) (32, 43, 61, 188, 199, 251). For example, IFN-γ−/− mice have relatively high bacterial loads and mild gastritis, whereas IL-10−/− mice have relatively low bacterial loads and severe gastritis (43). As will be discussed later in this review, these observations are relevant to understanding the immunologic basis for protective immunity to H. pylori.

Th1 and Th2 Responses in Mice

The data described above, involving experiments with various knockout mice, suggest that expression of IFN-γ (a Th1 cytokine) contributes to enhanced gastric inflammation, whereas expression of certain Th2 cytokines (IL-10 and possibly IL-4) contributes to diminished inflammation. To investigate further the role of Th1 and Th2 responses in modulating gastric inflammation, C57BL/6 mice were initially infected with a nematode that induces a strong Th2 response and then were challenged with H. felis (72). In comparison to mice infected with H. felis alone, the mice coinfected with H. felis and the nematode had reduced gastric expression of Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-1β), increased gastric expression of Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, and transforming growth factor β), and reduced gastric inflammatory scores (72). These data provide support for the hypothesis that a Th2-polarized response down-regulates the severity of H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation.

Several cytokines affect the expression of gastric hormones that control gastric acid secretion. Expression of gastrin, a hormone that stimulates gastric acid secretion, is stimulated by IFN-γ (257), and expression of somatostatin, a hormone that inhibits gastric acid secretion, is stimulated by IL-4 and inhibited by IFN-γ and TNF (25, 257). Increased expression of IFN-γ (a Th1 response) is expected to result in increased gastrin production, whereas expression of IL-4 (a Th2 response) is expected to result in increased somatostatin production and reduced gastrin secretion. One study used a mouse model of H. felis infection to investigate the effects of IL-4-induced alterations on gastrin and somatostatin expression (257). As expected, administration of IL-4 resulted in increased somatostatin expression and reduced gastrin expression. These changes were accompanied by a reduction in the severity of H. felis-induced gastritis. The modulatory effects of IL-4 on the severity of gastric inflammation were observed in H. felis-infected wild-type mice but not in infected somatostatin knockout mice, which suggested that the IL-4-induced alterations in inflammation were mediated through effects of IL-4 on somatostatin production by D cells (257).

Role of Regulatory T Cells

The gastric mucosal inflammatory response to H. pylori may be regulated in part by regulatory T cells (Tregs) (CD25+ CD45RBlo T cells). CD4+/CD25+ Tregs can suppress cytokine production and proliferation of other T cells (118). One recent study investigated the role of Tregs in a murine model of H. pylori-induced gastritis by reconstituting athymic C57BL/6 nude mice (T-cell-deficient nu/nu mice) with either lymph node cells containing CD25+ cells or lymph node cells depleted of CD25+ cells, 3 weeks prior to H. pylori infection (188). In mice reconstituted with a cell population depleted of Tregs, a relatively severe gastritis occurred by 6 weeks postinfection compared to that which occurred in mice reconstituted with a nonsorted T-cell population (containing both CD25+ and CD25− T cells). The mice reconstituted with a T-cell population lacking CD25+ cells developed a stronger Th1 response, characterized by increased numbers of CD4+ T cells in the mucosa and increased IFN-γ production compared to mice reconstituted with an unsorted T-cell population (188). These data indicate that Tregs have an important role in regulating the gastric mucosal inflammatory response to H. pylori.

Protective Immunity in Animal Models

Protective immunity to H. pylori may be defined as either (i) immunity that protects against H. pylori colonization of the stomach or (ii) an immune response that results in eradication of an established infection. Both prophylactic H. pylori immunization (to prevent future infection) and therapeutic immunization (to eradicate an established infection) have been successfully accomplished in animal models (50, 106, 142, 195).

Several early studies suggested that protection might be mediated by Helicobacter-specific antibodies (30, 48, 69, 122). Subsequently, it was shown that immunization of μ-MT mice (which are unable to produce antibodies) or IgA-deficient mice can result in protective immunity against H. pylori or H. felis infection (3, 31, 67, 76, 84, 221). Therefore, there is now a general consensus that H. pylori-specific antibodies are not required for protective immunity.

Cellular immune responses seem to have an important role in protective immunity against H. pylori. Mice deficient in CD8+ T cells (MHC class I−/− mice) can be successfully immunized and protected against colonization with H. pylori (177), whereas mice deficient in CD4+ T cells (MHC class II−/− mice) were not protected by prophylactic immunization against H. pylori (177). CD4+ T cells from H. felis-immunized mice can mediate protective immunity if adoptively transferred into immunodeficient Rag1−/− mice (84). These data suggest that CD4+ T cells, but not CD8+ cells, are necessary for protection (67, 177).

Several lines of evidence suggest that Th2-type responses might be required for protective immunity against H. pylori. Specifically, persistent H. pylori infections in humans and mice typically result in Th1-polarized responses, whereas successful Helicobacter immunization of animals typically results in Th2-polarized responses (1, 50). In addition, adoptive transfer of Th2 cells from H. felis-infected C57BL/6 mice into infected C57BL/6 mice significantly reduced the bacterial load compared to when Th1 cells were adoptively transferred (151). Conversely, there is evidence that a Th2 response may not be required for protection. Specifically, IL-4 and IL-5 knockout C57BL/6 mice were successfully protected from H. pylori infection following immunization (76). In addition, studies with IL-4 receptor α-chain-deficient BALB/c mice (which lack both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling) suggested that IL-4 and IL-13 are not required for a protective immune response (129). Whether IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells are required for protective immunity is not yet completely clear (75, 199). However, immunization studies using IL-12 and IL-18 knockout mice indicate that these two Th1 cytokines are required for effective protection against H. pylori and suggest that the establishment of an active Th1-type response is required for protection (2, 4, 75). In summary, the role of Th1-type versus Th2-type immune responses in protective immunity to H. pylori infection remains incompletely understood. Differences in the mouse strain backgrounds used in various studies potentially complicate interpretation of the data.

There is evidence that protective immunity against H. pylori in prophylactically immunized mice may require mast cells. In contrast to immunized wild-type mice, immunized mast cell-deficient mice (W/W v mice) were not protected from challenge with H. felis (238). Reconstitution of W/W v mice with bone marrow-derived mast cells restored the ability of W/W v mice to develop a protective immune response following prophylactic vaccination (238). The mechanism by which the mast cells contribute to protective immunity is undefined, but it may be hypothesized that mast cells modulate the activity of T cells or neutrophils through secretion of cytokines or that mast cells have antibacterial activity via the production of nitric oxide or antimicrobial peptides.

Further insight into protective immunity against H. pylori can be gleaned by analyzing levels of H. pylori colonization (bacterial load or bacterial density) in persistently infected knockout mouse models. The levels of H. pylori colonization in SCID mice are significantly higher than those in wild-type mice (61). Conversely, the levels of H. pylori colonization in IL-10 knockout mice are about 100-fold lower than those in wild-type mice (43), and in some cases, H. pylori is completely eradicated from IL-10 knockout mice (104). Control of H. pylori proliferation in IL-10 knockout mice is associated with development of a gastric mucosal inflammatory response that is more severe than that in infected wild-type mice. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that protective immune responses leading to eradication of H. pylori are associated with relatively severe gastric mucosal inflammatory responses.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN H. PYLORI AND IMMUNE CELLS IN VITRO

As described in the previous sections of this review, H. pylori stimulates a gastric mucosal inflammatory response and resists clearance by host immune defenses. To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying these phenomena, interactions between H. pylori and various types of immune cells have been analyzed in vitro. Because H. pylori lives in the gastric mucus layer and does not typically breach the gastric epithelial barrier, contact between H. pylori and phagocytic cells may be fairly limited in vivo. Nevertheless, several publications have described ingestion of H. pylori by phagocytic cells in human gastric tissue (10, 97, 119, 173). Interactions between H. pylori and phagocytic cells probably occur when there are disruptions in the gastric epithelial barrier or in the setting of gastric mucosal injury. Interactions between H. pylori and intraepithelial T cells potentially occur commonly even in the absence of gastric epithelial disruptions.

Immune Recognition of H. pylori by Gastric Epithelial Cells

Toll-like receptors recognize conserved microbial components, termed “pathogen-associated molecular patterns,” and play an important role in initiating innate immune responses to bacterial pathogens. At least 13 different TLRs have been described, 10 of which are expressed in humans. Among the TLRs that recognize gram-negative bacteria, some of the most extensively characterized include TLR2 (which recognizes lipoproteins), TLR4 (gram-negative LPS), TLR5 (flagellin), and TLR9 (bacterial CpG DNA motifs) (223). H. pylori adheres to human gastric epithelial cells, and therefore TLRs on gastric epithelial cells would be expected to recognize H. pylori PAMPs in vivo. Gastric epithelial cells in the antrum and the corpus of the human stomach are reported to express TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9 (201). In H. pylori-negative patients, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9 are expressed at both the apical and basolateral poles of gastric epithelial cells. In contrast, in H. pylori-positive patients, TLR5 and TLR9 are expressed exclusively at the basolateral pole, and TLR4 is expressed at both poles (201). Localization of TLRs to the basolateral poles of epithelial cells would make it unlikely for adherent H. pylori to be recognized by these receptors. Cultured primary human gastric cells express TLR2 and TLR5 but not TLR4 (21).

Several studies have sought to characterize the interactions of H. pylori PAMPs with TLRs in vitro. These studies have used many different cell types, including primary gastric epithelial cells, gastric epithelial cell lines, and cell lines transfected with plasmids that express TLRs and/or TLR accessory proteins. It is possible that some of the gastric epithelial cell lines used in these experiments do not express certain TLR accessory proteins such as CD14 and MD-2, which are required for TLR4 signaling. Different sources of H. pylori PAMPs have been used, including intact bacteria, purified LPS, and flagellin. Because of the many variations in experimental design, the results of these studies have not been uniform. Nevertheless, several general conclusions can be drawn from these studies.

Analyses of the interactions of purified H. pylori LPS with TLRs suggest that, in contrast to LPSs from most other gram-negative bacteria, H. pylori LPS is not well recognized by TLR4 (21, 103, 206). One study provided evidence that H. pylori LPS may act as an antagonist for TLR4 (124). H. pylori LPS induced NF-κB activation in HEK293 cells that expressed TLR2 but not in HEK293 cells that expressed TLR4 (206). These data suggest that H. pylori LPS may be recognized by TLR2 instead of by TLR4. H. pylori Hsp60 also is reported to be recognized by TLR2 (224).

Unlike flagellins from gram-negative organisms such as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, H. pylori flagellin is not recognized by TLR5 (12, 79, 123). This evasion of TLR5 recognition is attributable to alterations in H. pylori FlaA amino acid sequences in the TLR5 recognition site. If the corresponding amino acids are mutated in FlaA from Salmonella, the resulting Salmonella mutant strain is not recognized by TLR5 (12). Thus, H. pylori expresses at least two PAMPs (LPS and flagellin) that are recognized relatively poorly by TLRs and that may not trigger a strong innate immune response.

Recognition of intact H. pylori organisms by cultured epithelial cells appears to be dependent on TLR2 and TLR5 and to be independent of TLR4 (136, 141, 206). In one study, dominant negative forms of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR5 were expressed in the human gastric cancer cell line MKN45, and the cells then were incubated with H. pylori (206). The expression of chemokines (ΜIP3α, IL-8, and GROα) in these cells in response to H. pylori was dependent on TLR2 and TLR5 signaling but not on TLR4 signaling. These studies suggest that intact H. pylori organisms can be recognized by TLR5, despite poor recognition of H. pylori flagellin by TLR5. Potentially H. pylori components other than flagellin are recognized by TLR5, or perhaps the results are influenced by variations in the methodology used in different studies.

In addition to recognition of H. pylori PAMPs by TLRs, H. pylori peptidoglycan can be recognized by Nod1 (CARD4), an intracellular pathogen recognition molecule (239). There is evidence that the type IV secretion system encoded by the H. pylori cag PAI delivers H. pylori peptidoglycan into epithelial cells. Intracellular recognition of H. pylori peptidoglycan by Nod1 leads to activation of NF-κB and altered gene transcription in host cells (239). Compared to gastric epithelial cells from wild-type mice, gastric epithelial cells from Nod1-deficient mice produced significantly less macrophage inflammatory protein-2 in response to H. pylori (239).

In summary, H. pylori can be recognized in vitro by TLRs as well as the Nod1 receptor, and such recognition probably contributes to initiation of an innate immune response in vivo (Fig. 3). There is no evidence that H. pylori can evade detection by TLRs, but certain H. pylori PAMPs, such as LPS and flagellin, seem to be poorly recognized by TLRs. This may represent a mechanism by which H. pylori down-regulates the intensity of the innate immune response.

FIG. 3.

Innate immune recognition of H. pylori. Innate immune recognition of H. pylori leads to production of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages (Mφ), DCs, mast cells, and gastric epithelial cells. Innate immune recognition of H. pylori is mediated at least in part through TLRs. In addition, H. pylori peptidoglycan (PG) can be recognized by intracellular Nod receptors (239). Interactions between H. pylori and gastric epithelial cells lead to activation of NF-κB and alteration in gene transcription in the epithelial cells. Production of IL-8 by epithelial cells leads to recruitment of neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]), which can phagocytose opsonized bacteria and produce reactive oxygen species (ROI) or reactive nitrogen species (RNI). The activation of mast cells results in degranulation and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

It should be noted that the interactions of H. pylori with gastric epithelial cells are dependent on characteristics of the H. pylori strain. H. pylori strains possessing certain adhesins bind to gastric epithelial cells more efficiently than do strains that lack these adhesins (102). Strains that possess the cag PAI stimulate epithelial cells to produce relatively high levels of proinflammatory cytokines compared to strains that lack the cag PAI (5, 38, 71, 87, 125, 161, 205, 239). In addition, strains possessing the cag PAI and expressing a functionally active form of VacA can cause structural alterations in gastric epithelial cells (46, 95). Both CagA and VacA have been implicated in increasing the permeability of gastric epithelial monolayers (11, 176). A consequence may be entry of H. pylori antigens into the lamina propria, which would be expected to trigger an inflammatory response.

Interactions of H. pylori with Neutrophils

Neutrophils are recruited when H. pylori initially colonizes the human stomach (85, 191), and the gastric mucosal inflammatory response that occurs in the setting of persistent H. pylori infection is characterized by infiltration of neutrophils (194, 246). Several specific H. pylori factors are known to interact with neutrophils and modulate their function.

H. pylori produces a 150-kDa oligomeric protein known as neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP), which is chemotactic for neutrophils and activates neutrophils in vitro (68). HP-NAP stimulates neutrophils to produce reactive oxygen intermediates, and in response to HP-NAP, neutrophils release Ca2+ and phosphorylate cytosolic cellular signaling molecules (197). In addition, HP-NAP induces expression of β2-integrins on the surface of neutrophils (197).

An H. pylori outer membrane protein, SabA, also has an important role in human neutrophil activation (235). Wild-type strains of H. pylori expressing SabA activate neutrophils, whereas mutant and wild-type strains lacking SabA do not (235). There is evidence that binding of H. pylori to neutrophils through SabA-mediated adhesion may stimulate a G-protein-linked signaling pathway and downstream activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (235).

Whether H. pylori can resist phagocytosis by neutrophils is not yet completely resolved (7, 170), but one study reported that uptake of unopsonized H. pylori by neutrophils was inefficient compared to uptake of latex-coated beads and that H. pylori could inhibit phagocytosis of latex-coated beads or Neisseria gonorrhoeae (189). If nonopsonized H. pylori organisms are phagocytosed by neutrophils, the bacteria are able to resist intracellular killing (7, 227). One mechanism by which nonopsonized H. pylori evades intracellular killing may involve disruption of NADPH oxidase targeting, such that superoxide anions generated in the oxidative burst do not accumulate in the phagosome but instead are released into the extracellular space (7). A catalase-dependent pathway also may have a role in allowing nonopsonized H. pylori to evade intracellular killing (189).

The migration of neutrophils in response to chemokines IL-8 and Groα is mediated through the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 (163). H. pylori can down-regulate the expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 in human neutrophils in vitro, and this is predicted to have an inhibitory effect on neutrophil migration (202). In summary, multiple H. pylori factors can activate neutrophils, and there is also evidence that H. pylori can interfere with the proper functioning of neutrophils.

Interactions of H. pylori with Mast Cells

In vitro experiments indicate that whole H. pylori bacteria (250) and various H. pylori components can activate mast cells. One H. pylori factor that can activate mast cells is VacA. VacA can induce mast cell chemotaxis and can stimulate mast cell expression of multiple proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, TNF, IL-6, IL-13, and IL-10 (49, 220). VacA induces degranulation of the mast cell line RBL-2H3 but does not induce degranulation of murine bone marrow-derived mast cells (49, 220). HP-NAP also can activate mast cells, resulting in β-hexosaminidase release and IL-6 production (156). Activation of mast cells by H. pylori may contribute to the inflammatory response associated with H. pylori infection.

Interactions of H. pylori with Macrophages

Contact between macrophages and intact H. pylori bacteria or H. pylori components results in macrophage activation and the secretion of numerous cytokines and chemokines (81, 93, 140). Macrophages recognize H. pylori LPS via TLR4 (35, 136) and can also be activated by H. pylori proteins, including urease and Hsp60 (81, 93). Macrophage recognition of intact H. pylori can be mediated by TLR2 or TLR4 (141, 216).

Although not all studies have reached identical conclusions (170), at least one study reported that H. pylori is able to inhibit its own uptake by macrophages (190). When nonopsonized H. pylori organisms are internalized by macrophages, they initially localize in phagosomes, which then coalesce into “megasomes” that contain multiple bacteria (8, 193). Ingested H. pylori cells have at least some ability to resist intracellular killing (8). One study reported that phagolysosomal fusion is impaired in H. pylori-infected macrophages through retention of the tryptophan aspartate-containing coat protein on phagosomes, a phenomenon that is expected to result in increased intracellular survival of the bacteria (258).

Phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages typically results in localization of the microorganisms within phagosomes that contain protein kinase C (PKC) isoform α (39). PKC activation plays a role in the respiratory burst and phagosome-lysosome fusion (120). Upon phagocytosis of nonopsonized H. pylori by macrophages, PKC isoforms ζ and ɛ accumulate on the forming phagosomes, but the conventional PKC isoform α does not (6). Experiments using specific PKC inhibitors suggest that PKC ζ regulates actin rearrangement and H. pylori engulfment (6) and that phagocytosis of nonopsonized H. pylori by macrophages may occur via a novel PKC ζ-regulated pathway. The ability of nonopsonized H. pylori to resist macrophage killing may be attributable to features of this PKC ζ-mediated phagocytic process. Opsonized H. pylori is phagocytosed by a PKC ζ-independent process, which is likely to involve conventional pathways (6).

One mechanism by which H. pylori impairs the antimicrobial activity of macrophages involves expression of catalase. In comparison to a wild-type catalase-positive H. pylori strain, an isogenic, catalase-deficient strain was more susceptible to macrophage-mediated killing (23). Another mechanism by which H. pylori resists macrophage killing is by blocking the production of nitric oxide. This effect is mediated by H. pylori arginase, which competes with nitric oxide synthase for arginine (83). In addition to resisting killing by macrophages, in vitro experiments indicate that H. pylori can induce macrophage apoptosis (41, 44, 82). H. pylori-induced apoptosis of macrophages may result in impaired innate and adaptive immune responses.

Interactions of H. pylori with Dendritic Cells

In response to H. pylori, monocyte-derived human DCs express costimulatory molecules and major histocompatibility complex class II proteins (92, 115), which results in increased efficiency of antigen presentation. H. pylori also stimulates dendritic cell expression of multiple cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12 (88, 115, 240). Similar to several other bacterial pathogens, H. pylori can bind to DC-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), a DC-specific lectin (15, 27). The expression of cytokines by DCs in response to H. pylori is modulated by interactions between H. pylori LPS Le antigens (Lex, Ley, Lea, or Leb) and DC-SIGN (27). Dendritic cells incubated with Le antigen-negative H. pylori strains express more IL-6 and less IL-10 than do dendritic cells incubated with Le antigen-positive H. pylori (27). Given that IL-10 is known to down-regulate inflammatory responses, the interactions between H. pylori LPS Le antigens and DC-SIGN may contribute to suppression of inflammation.

Interactions of H. pylori with B Lymphocytes

H. pylori is reported to have several inhibitory effects on B lymphocytes (152, 234). In one study, H. pylori VacA interfered with the prelysosomal processing of tetanus toxin in Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells, and the ability of these cells to stimulate human CD4+ T cells was impaired in the presence of VacA (152). VacA inhibited the Ii-dependent pathway of antigen presentation mediated by newly synthesized MHC class II molecules but did not affect the pathway dependent on recycling MHC class II (152). Expression of CagA in B cells is reported to inhibit interleukin-3-dependent B-cell proliferation by inhibiting JAK-STAT signaling, which may result in inefficient antibody production and reduced cytokine expression (234).

Interactions of H. pylori with T Lymphocytes

In vitro experiments indicate that live H. pylori or H. pylori products can interfere with multiple functions of T lymphocytes (37, 77, 78, 219, 256) (Fig. 4). One report indicated that H. pylori can have proapoptotic effects on T cells (242), but most of the observed effects occur in the absence of cell death. Coincubation of H. pylori with T cells results in diminished expression of IL-2 and IL-2 receptor (CD25), inhibition of activation-induced proliferation, and cell cycle arrest (37, 77, 78, 219, 256).

FIG. 4.

Effects of H. pylori on T lymphocytes. Multiple H. pylori factors can suppress T-cell activity. VacA inhibits NFAT activity in T cells, leading to diminished IL-2 production, and also inhibits T-cell proliferation (37, 77, 219). Arginase inhibits T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling (256). An unidentified low-molecular-weight protein has been reported to inhibit T-cell proliferation by blocking cell cycle progression (78).

The effects of H. pylori on T cells are mediated by several different bacterial factors, one of which is VacA. VacA interferes with the activity of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), a transcription factor that regulates immune response genes, in Jurkat T cells, resulting in inhibition of IL-2 expression and G1/S cell cycle arrest (37, 77). The effects of VacA on Jurkat cells may be mediated by blocking calcium influx, thereby interfering with the activity of the calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin, which is required for NFAT activation (37, 77). VacA also activates intracellular signaling in T cells through mitogen-activated protein kinases MKK3/6 and p38 and the Rac-specific nucleotide exchange factor Vav, thereby causing disorganized actin polymerization (37). Studies of VacA effects on primary human CD4+ T cells indicate that VacA can also inhibit T-cell proliferation through a process that is not dependent on inhibition of NFAT (219).

H. pylori arginase also contributes to inhibition of T-cell proliferation. One study reported that incubation of T cells with a wild-type H. pylori strain, but not an arginase mutant strain, caused decreased expression of the CD3ζ chain of the T-cell receptor (256). In addition to VacA and arginase, an uncharacterized low-molecular-weight protein of H. pylori has been reported to inhibit proliferation of T lymphocytes (78). This low-molecular-weight H. pylori factor is reported to block cell cycle progression at the G1 phase.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

H. pylori persistently colonizes the human stomach despite development of a humoral and cellular immune response. Animal models have been very useful in identifying H. pylori factors that are required for colonization of the stomach and for elucidating the roles of various host factors in the development of gastric mucosal inflammation. A protective immune response to H. pylori can be elicited in animal models by immunization, but the immune effector components that mediate protection remain incompletely defined. H. pylori can alter the function of many different types of immune cells in vitro. These in vitro experiments provide important insights into the molecular mechanisms by which H. pylori resists immune clearance. However, further studies are needed to determine which in vitro interactions are most relevant in vivo. Future studies, directed toward understanding interactions between H. pylori and immune cells in vivo, are expected to lead to important new insights into the mechanisms of H. pylori persistence and also may lead to the development of novel therapeutic approaches for eradication of H. pylori.

Acknowledgments

We regret that many relevant publications have not been cited here due to space limitations. We are grateful for stimulating discussions with members of the Cover, Peek, and Wilson laboratories.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI39657, R01 DK53623, and T32 AI 07474 and by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhiani, A. A. 2005. The role of type-specific antibodies in colonization and infection by Helicobacter pylori. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18:223-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhiani, A. A., J. Pappo, Z. Kabok, K. Schon, W. Gao, L. E. Franzen, and N. Lycke. 2002. Protection against Helicobacter pylori infection following immunization is IL-12-dependent and mediated by Th1 cells. J. Immunol. 169:6977-6984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhiani, A. A., K. Schon, L. E. Franzen, J. Pappo, and N. Lycke. 2004. Helicobacter pylori-specific antibodies impair the development of gastritis, facilitate bacterial colonization, and counteract resistance against infection. J. Immunol. 172:5024-5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhiani, A. A., K. Schon, and N. Lycke. 2004. Vaccine-induced immunity against Helicobacter pylori infection is impaired in IL-18-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 173:3348-3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akopyants, N. S., S. W. Clifton, D. Kersulyte, J. E. Crabtree, B. E. Youree, C. A. Reece, N. O. Bukanov, E. S. Drazek, B. A. Roe, and D. E. Berg. 1998. Analyses of the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 28:37-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen, L. A., and J. A. Allgood. 2002. Atypical protein kinase C-zeta is essential for delayed phagocytosis of Helicobacter pylori. Curr. Biol. 12:1762-1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen, L. A., B. R. Beecher, J. T. Lynch, O. V. Rohner, and L. M. Wittine. 2005. Helicobacter pylori disrupts NADPH oxidase targeting in human neutrophils to induce extracellular superoxide release. J. Immunol. 174:3658-3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen, L. A., L. S. Schlesinger, and B. Kang. 2000. Virulent strains of Helicobacter pylori demonstrate delayed phagocytosis and stimulate homotypic phagosome fusion in macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 191:115-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amedei, A., M. P. Bergman, B. J. Appelmelk, A. Azzurri, M. Benagiano, C. Tamburini, R. van der Zee, J. L. Telford, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, M. M. D'Elios, and G. Del Prete. 2003. Molecular mimicry between Helicobacter pylori antigens and H+,K+-adenosine triphosphatase in human gastric autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 198:1147-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amieva, M. R., N. R. Salama, L. S. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2002. Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4:677-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amieva, M. R., R. Vogelmann, A. Covacci, L. S. Tompkins, W. J. Nelson, and S. Falkow. 2003. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science 300:1430-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen-Nissen, E., K. D. Smith, K. L. Strobe, S. L. Barrett, B. T. Cookson, S. M. Logan, and A. Aderem. 2005. Evasion of Toll-like receptor 5 by flagellated bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:9247-9252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appelmelk, B. J., Y. Q. An, M. Geerts, B. G. Thijs, H. A. de Boer, D. M. MacLaren, J. de Graaff, and J. H. Nuijens. 1994. Lactoferrin is a lipid A-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 62:2628-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appelmelk, B. J., S. L. Martin, M. A. Monteiro, C. A. Clayton, A. A. McColm, P. Zheng, T. Verboom, J. J. Maaskant, D. H. van den Eijnden, C. H. Hokke, M. B. Perry, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and J. G. Kusters. 1999. Phase variation in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide due to changes in the lengths of poly(C) tracts in α3-fucosyltransferase genes. Infect. Immun. 67:5361-5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appelmelk, B. J., I. van Die, S. J. van Vliet, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, T. B. Geijtenbeek, and Y. van Kooyk. 2003. Cutting edge: carbohydrate profiling identifies new pathogens that interact with dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin on dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 170:1635-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aras, R. A., W. Fischer, G. I. Perez-Perez, M. Crosatti, T. Ando, R. Haas, and M. J. Blaser. 2003. Plasticity of repetitive DNA sequences within a bacterial (type IV) secretion system component. J. Exp. Med. 198:1349-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archimandritis, A., S. Sougioultzis, P. G. Foukas, M. Tzivras, P. Davaris, and H. M. Moutsopoulos. 2000. Expression of HLA-DR, costimulatory molecules B7-1, B7-2, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and Fas ligand (FasL) on gastric epithelial cells in Helicobacter pylori gastritis; influence of H. pylori eradication. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 119:464-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asahi, M., T. Azuma, S. Ito, Y. Ito, H. Suto, Y. Nagai, M. Tsubokawa, Y. Tohyama, S. Maeda, M. Omata, T. Suzuki, and C. Sasakawa. 2000. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein can be tyrosine phosphorylated in gastric epithelial cells. J. Exp. Med. 191:593-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aspinall, G. O., and M. A. Monteiro. 1996. Lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori strains P466 and MO19: structures of the O antigen and core oligosaccharide regions. Biochemistry 35:2498-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayraud, S., B. Janvier, and J. L. Fauchere. 2002. Experimental colonization of mice by fresh clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori is not influenced by the cagA status and the vacA genotype. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 34:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Backhed, F., B. Rokbi, E. Torstensson, Y. Zhao, C. Nilsson, D. Seguin, S. Normark, A. M. Buchan, and A. Richter-Dahlfors. 2003. Gastric mucosal recognition of Helicobacter pylori is independent of Toll-like receptor 4. J. Infect. Dis. 187:829-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bamford, K. B., X. Fan, S. E. Crowe, J. F. Leary, W. K. Gourley, G. K. Luthra, E. G. Brooks, D. Y. Graham, V. E. Reyes, and P. B. Ernst. 1998. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori infection have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology 114:482-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basu, M., S. J. Czinn, and T. G. Blanchard. 2004. Absence of catalase reduces long-term survival of Helicobacter pylori in macrophage phagosomes. Helicobacter 9:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer, F., K. Schweimer, E. Kluver, J. R. Conejo-Garcia, W. G. Forssmann, P. Rosch, K. Adermann, and H. Sticht. 2001. Structure determination of human and murine beta-defensins reveals structural conservation in the absence of significant sequence similarity. Protein Sci. 10:2470-2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beales, I., J. Calam, L. Post, S. Srinivasan, T. Yamada, and J. DelValle. 1997. Effect of transforming growth factor alpha and interleukin 8 on somatostatin release from canine fundic D cells. Gastroenterology 112:136-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg, D. J., N. A. Lynch, R. G. Lynch, and D. M. Lauricella. 1998. Rapid development of severe hyperplastic gastritis with gastric epithelial dedifferentiation in Helicobacter felis-infected IL-10(−/−) mice. Am. J. Pathol. 152:1377-1386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergman, M. P., A. Engering, H. H. Smits, S. J. van Vliet, A. A. van Bodegraven, H. P. Wirth, M. L. Kapsenberg, C. M. J. E. Vanderbroucke-Grauls, Y. van Kooyk, and B. J. Appelmelk. 2004. Helicobacter pylori modulates the T helper cell 1/T helper cell 2 balance through phase-variable interaction between lipopolysaccharide and DC-SIGN. J. Exp. Med. 200:979-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berstad, A. E., M. Kilian, K. N. Valnes, and P. Brandtzaeg. 1999. Increased mucosal production of monomeric IgA1 but no IgA1 protease activity in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Am. J. Pathol. 155:1097-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betten, A., J. Bylund, T. Cristophe, F. Boulay, A. Romero, K. Hellstrand, and C. Dahlgren. 2001. A proinflammatory peptide from Helicobacter pylori activates monocytes to induce lymphocyte dysfunction and apoptosis. J. Clin. Investig. 108:1221-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanchard, T. G., S. J. Czinn, R. Maurer, W. D. Thomas, G. Soman, and J. G. Nedrud. 1995. Urease-specific monoclonal antibodies prevent Helicobacter felis infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 63:1394-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanchard, T. G., S. J. Czinn, R. W. Redline, N. Sigmund, G. Harriman, and J. G. Nedrud. 1999. Antibody-independent protective mucosal immunity to gastric Helicobacter infection in mice. Cell. Immunol. 191:74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanchard, T. G., F. Yu, C. L. Hsieh, and R. W. Redline. 2003. Severe inflammation and reduced bacteria load in murine Helicobacter infection caused by lack of phagocyte oxidase activity. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1609-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blaser, M. J. 2005. The biology of cag in the Helicobacter pylori-human interaction. Gastroenterology 128:1512-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blaser, M. J., and J. C. Atherton. 2004. Helicobacter pylori persistence: biology and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 113:321-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bliss, C. M., Jr., D. T. Golenbock, S. Keates, J. K. Linevsky, and C. P. Kelly. 1998. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide binds to CD14 and stimulates release of interleukin-8, epithelial neutrophil-activating peptide 78, and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 by human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 66:5357-5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bogstedt, A. K., S. Nava, T. Wadstrom, and L. Hammarstrom. 1996. Helicobacter pylori infections in IgA deficiency: lack of role for the secretory immune system. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 105:202-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boncristiano, M., S. R. Paccani, S. Barone, C. Ulivieri, L. Patrussi, D. Ilver, A. Amedei, M. M. D'Elios, J. L. Telford, and C. T. Baldari. 2003. The Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin inhibits T cell activation by two independent mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 198:1887-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandt, S., T. Kwok, R. Hartig, W. Konig, and S. Backert. 2005. NF-κB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:9300-9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breton, A., and A. Descoteaux. 2000. Protein kinase C-alpha participates in FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276:472-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Censini, S., C. Lange, Z. Xiang, J. E. Crabtree, P. Ghiara, M. Borodovsky, R. Rappuoli, and A. Covacci. 1996. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14648-14653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaturvedi, R., Y. Cheng, M. Asim, F. I. Bussiere, H. Xu, A. P. Gobert, A. Hacker, R. A. Casero, Jr., and K. T. Wilson. 2004. Induction of polyamine oxidase 1 by Helicobacter pylori causes macrophage apoptosis by hydrogen peroxide release and mitochondrial membrane depolarization. J. Biol. Chem. 279:40161-40173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, W., D. Shu, and V. S. Chadwick. 1999. Helicobacter pylori infection in interleukin-4-deficient and transgenic mice. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 34:987-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen, W., D. Shu, and V. S. Chadwick. 2001. Helicobacter pylori infection: mechanism of colonization and functional dyspepsia. Reduced colonization of gastric mucosa by Helicobacter pylori in mice deficient in interleukin-10. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16:377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng, Y., R. Chaturvedi, M. Asim, F. I. Bussiere, H. Xu, R. A. Casero, Jr., and K. T. Wilson. 2005. Helicobacter pylori-induced macrophage apoptosis requires activation of ornithine decarboxylase by c-Myc. J. Biol. Chem. 280:22492-22496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Correa, P. 1992. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process. Cancer Res. 52:6735-6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cover, T. L., and S. R. Blanke. 2005. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:320-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crabtree, J. E., T. M. Shallcross, R. V. Heatley, and J. I. Wyatt. 1991.. Mucosal tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 in patients with Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis. Gut 32:1473-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Czinn, S. J., A. Cai, and J. G. Nedrud. 1993. Protection of germ-free mice from infection by Helicobacter felis after active oral or passive IgA immunization. Vaccine 11:637-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Bernard, M., A. Cappon, L. Pancotto, P. Ruggiero, J. Rivera, G. Del Giudice, and C. Montecucco. 2005. The Helicobacter pylori VacA cytotoxin activates RBL-2H3 cells by inducing cytosolic calcium oscillations. Cell. Microbiol. 7:191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Del Giudice, G., A. Covacci, J. L. Telford, C. Montecucco, and R. Rappuoli. 2001. The design of vaccines against Helicobacter pylori and their development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:523-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D'Elios, M. M., M. P. Bergman, A. Amedei, B. J. Appelmelk, and G. Del Prete. 2004. Helicobacter pylori and gastric autoimmunity. Microbes Infect. 6:1395-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D'Elios, M. M., M. Manghetti, M. De Carli, F. Costa, C. T. Baldari, D. Burroni, J. L. Telford, S. Romagnani, and G. Del Prete. 1997. T helper 1 effector cells specific for Helicobacter pylori in the gastric antrum of patients with peptic ulcer disease. J. Immunol. 158:962-967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deml, L., M. Aigner, J. Decker, A. Eckhardt, C. Schutz, P. R. Mittl, S. Barabas, S. Denk, G. Knoll, N. Lehn, and W. Schneider-Brachert. 2005. Characterization of the Helicobacter pylori cysteine-rich protein A as a T-helper cell type 1 polarizing agent. Infect. Immun. 73:4732-4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Tommaso, A., Z. Xiang, M. Bugnoli, P. Pileri, N. Figura, P. F. Bayeli, R. Rappuoli, S. Abrignani, and M. T. De Magistris. 1995. Helicobacter pylori-specific CD4+ T-cell clones from peripheral blood and gastric biopsies. Infect. Immun. 63:1102-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dixon, M. F., R. M. Genta, J. H. Yardley, and P. Correa. 1996. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 20:1161-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dooley, C. P., H. Cohen, P. L. Fitzgibbons, M. Bauer, M. D. Appleman, G. I. Perez-Perez, and M. J. Blaser. 1989. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:1562-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dubois, A., D. E. Berg, E. T. Incecik, N. Fiala, L. M. Heman-Ackah, J. Del Valle, M. Yang, H. P. Wirth, G. I. Perez-Perez, and M. J. Blaser. 1999. Host specificity of Helicobacter pylori strains and host responses in experimentally challenged nonhuman primates. Gastroenterology 116:90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dubois, A., N. Fiala, L. M. Heman-Ackah, E. S. Drazek, A. Tarnawski, W. N. Fishbein, G. I. Perez-Perez, and M. J. Blaser. 1994. Natural gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori in monkeys: a model for spiral bacteria infection in humans. Gastroenterology 106:1405-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eaton, K. A., and S. Krakowka. 1994. Effect of gastric pH on urease-dependent colonization of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 62:3604-3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eaton, K. A., M. Mefford, and T. Thevenot. 2001. The role of T cell subsets and cytokines in the pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in mice. J. Immunol. 166:7456-7461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eaton, K. A., S. R. Ringler, and S. J. Danon. 1999. Murine splenocytes induce severe gastritis and delayed-type hypersensitivity and suppress bacterial colonization in Helicobacter pylori-infected SCID mice. Infect. Immun. 67:4594-4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eaton, K. A., S. Suerbaum, C. Josenhans, and S. Krakowka. 1996. Colonization of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori deficient in two flagellin genes. Infect. Immun. 64:2445-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El-Omar, E. M. 2001. The importance of interleukin 1beta in Helicobacter pylori associated disease. Gut 48:743-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]