Abstract

The genome of the human pathogen group A Streptococcus (GAS) encodes the transporters MtsABC, FtsABCD, and HtsABC to take up ferric and manganese ions, ferric ferrichrome, and heme, respectively. The GAS genome also encodes two metalloregulators PerR and MtsR. To understand the regulation of the expression of these transporters, the mtsR and perR deletion mutants of a GAS serotype M1 strain were generated, and the effects of the deletions and Fe3+, Mn2+, and Zn2+ on the expression of mtsA, htsA, and ftsB were examined. Mn2+ dramatically depresses mtsA transcription and levels of the MtsA protein but does not downregulate the expression of htsA and ftsB. Fe3+ decreases the expression of mtsA and htsA but has no effect on ftsB expression. Zn2+ has no effect on the expression of all three genes. The deletion of mtsR abolishes the Mn2+- and Fe3+-induced depression of mtsA expression and the Fe3+-dependent decrease in htsA expression. The deletion of mtsR does not significantly alter GAS virulence in a mouse model of subcutaneous infection. The deletion of perR does not affect the expression of the genes in response to the metal ions. MtsR binds to the mts promoter region in the presence of Mn2+ or Fe2+. The results indicate that MtsR differentially regulates the expression of mtsABC and htsABC.

Nutrient metal ions, such as iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn), are essential to bacterial pathogens. However, the metal ions in excess are toxic to bacteria. Therefore, the acquisition processes for metal ions are tightly regulated. Metal ion-dependent repression of transcription of genes encoding metal ion transporters is a primary mechanism in regulation of the acquisition processes. The transcriptional repression is mediated by metal-dependent transcription repressors. When metal ions are abundant, they bind to specific repressors, and the metal-repressor complexes bind to operators to block the transcription of relevant transporter genes. A number of metal-dependent transcription regulators have been described in bacteria, including the Fur family of Fur (9, 23), Zur (10), PerR (22), and Mur (7) and the DtxR family of DtxR (29), SirR (11), MntR (1), SloR (25), TroR (26), IdeR (28), and MtsR (2). These regulators are specific for Zn, Fe, Mn, or Fe plus Mn.

Streptococcus pyogenes or group A Streptococcus (GAS) is an important human pathogen causing common pharyngitis and other diseases, such as streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, necrotizing fasciitis, and rheumatic fever (6). Three ATP-binding cassette type (ABC) transporters of GAS, MtsABC, FtsABCD, and HtsABC, take up Fe3+ and Mn2+ (14), ferric ferrichrome (8), and heme (3, 17, 18, 20, 24), respectively. GAS produces two metalloregulators, PerR and MtsR, which are homologous to Fur and DtxR, respectively. PerR is involved in the response of GAS to oxidative stress (5, 15), and inactivation of perR decreases mtsA expression (27). Whether PerR directly regulates mtsABC and the other two transporters in response to metal ions is not known. MtsR has been shown to regulate the expression of HtsABC in response to Fe (2). Whether MtsR regulates MtsABC and FtsABCD remains unknown. To obtain an overall understanding of the regulation of these transporters, GAS mutant strains defective in mtsR or perR were generated, and the expression of the transporters were compared among wild-type (wt) and mutant strains in response to Fe3+, Mn2+, and Zn2+. We found that MtsR displays a different metal ion specificity in regulating the expression of mtsABC and htsABC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth.

GAS strain MGAS5005 (serotype M1) has been described previously (12). Isogenic MGAS5005 mutant strains are described below. GAS was grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Spectinomycin (150 mg/liter) or spectinomycin and/or chloramphenicol (20 mg/liter) were routinely added to THY for maintaining GAS mutant strains and their derivatives. Metal ion-restricted conditions were achieved by treating THY overnight with 30 g of chelating resin Chelex 100 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/liter, sterilizing by filtration, and supplementation with 1.0 mM MgCl2 (DTHYMg) or 1.0 mM MgCl2 and FeCl3, MnCl2, or ZnSO4 at the indicated concentrations. Since free FeCl3 has extremely low solubility in water at physiological pH, the concentrations of FeCl3 specified are the concentrations added.

Construction of mtsR and perR deletion mutants.

The mtsR and perR were deleted by the gene replacement method (30). The upstream and downstream flanking fragments of the deleted internal fragment (bases 21 to 585) of mtsR were PCR amplified by using paired primers mtsRF1P1/mtsRF1P2 and mtsRF2P1/mtsRF2P2 (Table 1) and were sequentially cloned into pGRV (21) at the PstI/BglII and BamHI/SalI sites, respectively, to yield pGRVΔmtsR. pGRVΔperR was similarly constructed by using the flanking fragments of the deleted internal fragment (bases 154 to 685) of perR, which were PCR amplified by using paired primers perRF1P1-perRF1P2 and perRF2P1-perRF2P2. pGRVΔmtsR and pGRVΔperR were introduced into MGAS5005 by electroporation. The deletion mutants, which were resistant to spectinomycin and sensitive to chloramphenicol, were confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing analyses.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for gene inactivation and complementation

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon |

|---|---|---|

| mtsRF1P1 | AACTGCAGCTTTGCAATCAATTGTTTGGC | Upstream fragment of mtsR for mtsR deletion |

| mtsRF1P2 | GAAGATCTGTAATCTTCTTTATTAGGCGTC | |

| mtsRF2P1 | CGGGATCCGGCGACAAGGAACTTGTCATC | Downstream fragment of mtsR for mtsR deletion |

| mtsRF2P2 | AGTGTCGACTTCGGCCCAGACATTAATGAC | |

| perRF1P1 | CCTAAAAGCTTACTTGGAGTC | Upstream fragment of perR for perR deletion |

| perRF1P2 | GAAGATCTTAGATGCTCTAGGACATTTTC | |

| perRF2P1 | CGGGATCCCAGTTATTGCTTACGGGG | Downstream fragment of perR for perR deletion |

| perRF2P2 | AGTGTCGACTAAATTCCGATGCTCTCACA | |

| mtsRP1 | CGGATCCAATAATTATAAATAAGAGAAAGGCCAAACG | mtsR for complementation |

| mtsRP2 | AGGATCCTTAAAGGGCTGTGACATAAAG | |

| mtsRPP1 | ACCATGGCGCCTAATAAAGAAGATTAC | Recombinant MtsR production |

| mtsRPP2 | CGAATTCTTAAAGGGCTGTGACATAAAG | |

| mtsP1 | AACTGCAGCTTCTTTATTAGGCGTCATATC | mts promoter probe |

| mtsP2 | AACTGCAGTCATTCTCTTTCCCATCATTTC | |

| htsP1 | AACTGCAGTATCCTAAGGCTAGCTTTATC | hts promoter probe |

| htsP2 | AACTGCAGTGAGAACAAGGGCAGATATTG | |

| ftsP1 | AACTGCAGCTCTAGAGTATGTTGACGTTAG | fts promoter probe |

| ftsP2 | AACTGCAGTGAGGTCTTCAGCACTAATTG |

Plasmid pCMVmtsR for complementation of ΔmtsR.

A DNA fragment containing mtsR and its ribosome-binding site was amplified from MGAS5005 by using the primers mtsRP1 and mtsRP2. The PCR product was cloned into pCMV (8) at the BamHI site, yielding pCMVmtsR. The cloned gene was sequenced to rule out spurious mutations and confirm the desired orientation.

Analysis of gene transcription.

Transcripts of the target genes present in GAS were assessed by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis using total GAS RNA, specific probes (AlleLogic Biosciences) and primers, and an ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system (PE Applied Biosystems), as described previously (18). GAS grown under the indicated conditions was harvested at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2, 0.4, or 0.7. The harvested bacteria were immediately processed to isolate total RNA, as described previously (18). Control reactions that did not contain reverse transcriptase revealed no contamination of genomic DNA in all RNA samples.

Mouse antisera.

Anti-MtsA, anti-FtsB, and anti-phosphoglycerate kinase (anti-PGK) mouse antisera have been described (8). To raise HtsA mouse antisera, five female outbred CD-1 Swiss mice (4 to 6 weeks old; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were immunized subcutaneously with 50 μg of recombinant HtsA suspended in 200 μl of saline emulsified in 44 μl of monophosphoryl lipid A-synthetic trehalose dicorynomycolate adjuvant (Corixa, Hamilton, MT). Mice were boosted at weeks 2 and 4. Immune sera were collected 5 days after the second boost. Recombinant HtsA was prepared as described previously (19).

Western blot analysis.

The levels of MtsA, HtsA, FtsB, and PGK (control) proteins in GAS strains grown under different conditions were compared by Western blot analysis. GAS strains grown in 10 ml of DTHYMg without or with supplementation of MnCl2, ZnSO4, or FeCl3 were harvested at OD600 of 0.2, 0.4, or 0.7; washed with 1 ml of Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS); pelleted; and resuspended in 100 μl of DPBS. The cell suspensions were digested with 200 U of mutanolysin at 37°C for 2 h. The samples were briefly sonicated and mixed with an equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer. Proteins in 10 μl of each sample with or without further dilution were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes; probed with anti-MtsA, anti-HtsA, anti-FtsB, or anti-PGK antiserum; and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence as described previously (16).

Preparation of MtsR.

To prepare recombinant MtsR, the mtsR gene was cloned from MGAS5005 by using the primers mtsRPP1 and mtsRPP2. The PCR product was digested with NcoI and EcoRI and ligated into pET21d at the NcoI and EcoRI sites to yield pMTSR. Recombinant MtsR produced from this plasmid in Escherichia coli is tag free. The gene clone was sequenced to rule out the presence of spurious mutations. MtsR was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pMTSR. The bacteria were grown to an OD600 of approximately 0.5 in 4 liters of Luria-Bertani broth containing 100 mg of ampicillin/liter at 37°C, expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 6 h, and bacteria were harvested by centrifugation.

The cell paste obtained was sonicated on ice for 15 min in 60 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Tris-HCl/EDTA/PMSF). The sample was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was loaded to a DEAE Sepharose column (2.5 by 6 cm). The column was washed with 180 ml of Tris-HCl/EDTA/PMSF. The flowthrough and wash solution were pooled, adjusted to 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was brought to 70% saturation of (NH4)2SO4 to precipitate the proteins. The precipitate containing MtsR was dissolved in 8 ml of Tris-HCl/EDTA/PMSF and dialyzed against 3 liters of Tris-HCl/EDTA/PMSF overnight. The dialyzed sample was loaded on a DEAE Sepharose column (2.5 by 4 cm). The column was washed with 20 mM Tris-HCl, and bound proteins were eluted with a 300-ml gradient of 0 to 0.4 M NaCl in Tris-HCl. Fractions containing MtsR were pooled. The pool was adjusted to 1.0 M (NH4)2SO4 and loaded onto a phenyl Sepharose column (1.5 by 8 cm). MtsR was eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and concentrated with a P-20 Centricon filter device (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The MtsR obtained was >90% purity, as assessed by SDS-PAGE.

EMSA.

The promoter regions of mtsABC (180 bp), htsABC (200 bp), and ftsABCD (200 bp) were amplified from MGAS5005 genomic DNA and the primers listed in Table 1. A PstI site was engineered into the primers to generate a protruding 3′ end after PstI digestion of the PCR products for efficient labeling. The PCR products were digested with PstI and labeled with biotin at the 3′-OH group using a biotin 3′ end DNA labeling kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. An electrophoretic mobility gel shift assay (EMSA) was performed by using a LightShift chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the binding of MtsR to the mts probe was carried out in 20-μl reactions containing 0.4 of pmol probe, 100 μM MnCl2, 1 μg of sheared salmon sperm DNA, and 0 to 60 ng or 0 to 2.4 pmol of MtsR. To compare the MtsR binding to the promoter probes of the mts, hts, and fts transporters, 60 ng of MtsR was incubated with 1 mM EDTA for 5 min and then 0.4 pmol of probe and 1.1 mM MnCl2, FeSO4, or ZnSO4 in 20-μl reactions. The probe in 10-μl reaction mixtures was resolved in a 6% polyacrylamide gel in 45 mM Tris-borate buffer (pH 8.0) at 100 V for 42 min and then transferred to positively charged nylon membrane (Pierce) by using a Trans-Blot SD semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 15 V for 40 min. After being cross-linked under UV light for 20 min, probes were reacted with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Mouse infection.

GAS strains were harvested at exponential phase, washed with DPBS, and inoculated subcutaneously at the indicated inoculum sizes into groups of seven or eight 5-week-old female outbred CD-1 Swiss mice (Charles River Laboratory). Survival rates were examined daily for 9 days after inoculation. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Montana State University, Bozeman.

RESULTS

Transcription of mtsA, ftsB, htsA, mtsR, and perR.

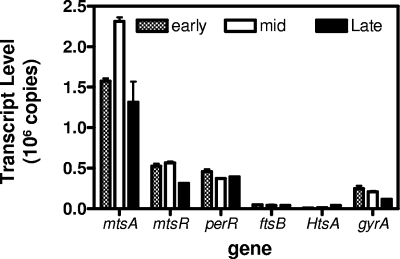

Real-time RT-PCR was used to determine the transcription levels and growth phase dependence of the transporters mtsABC, htsABC, and ftsABCD and metalloregulator genes. Based on the average transcript levels of each gene shown in Fig. 1, the relative transcript levels of htsA, ftsB, gyrA (control), perR, mtsR, and mtsA are 1, 2, 8.7, 18, 21, and 80, respectively. The transcript level of htsA at the late-exponential growth phase is 3.4 times those at the early- and mid-exponential growth phases. The variation of the transcript levels at the three growth phases are within 60 to 130% of the average for each of the other genes (Fig. 1), indicating limited growth-phase-dependent variation in their transcription. Since some strains grew relatively slowly at high Mn2+ concentrations, the early-exponential growth phase was chosen for the expression study unless otherwise specified.

FIG. 1.

Transcription of htsA, ftsB, mtsA, mtsR, perR, and gyrA. Real-time RT-PCR assays were performed with RNA isolated from MGAS5005 grown in THY to an OD600 of 0.2 (early exponential growth phase), 0.4 (mid-exponential growth phase), and 0.7 (late exponential growth phase). The transcript levels ± the standard deviations (SD) of triplicate measurements in 30 ng of total RNA are presented.

Depression of mtsA transcription by Mn2+.

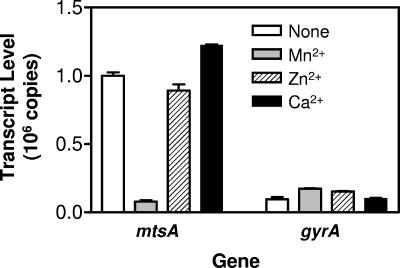

We previously reported that supplementation of DTHYMg with Ca2+, Zn2+, and Mn2+ dramatically decreases levels of mtsA transcript in GAS (18). To determine which metal ion depresses mtsA transcription, the levels of mtsA transcript were determined in GAS grown in DTHYMg supplemented with 100 μM Ca2+, Zn2+, or Mn2+. The levels of mtsA transcript in GAS grown in DTHYMg with Mn2+, Zn2+, and Ca2+ are 8, 89, and 122% of that without the metal supplements, respectively, and the levels of gyrA transcript do not change dramatically under all of the conditions (Fig. 2). These results indicate that Mn2+ induces the depression of mtsA transcription.

FIG. 2.

Effect of Mn2+ on mtsA transcription. GAS strain MGAS5005 was grown to an OD600 of 0.2 in DTHYMg without or with supplementation with 100 μM MnCl2, ZnSO4, or CaCl2, and the total RNA was isolated. Levels of mtsA and gyrA (control) transcripts in 30 ng of total RNA were determined by real-time RT-PCR analysis, and the transcript levels ± the SD of triplicate measurements are presented.

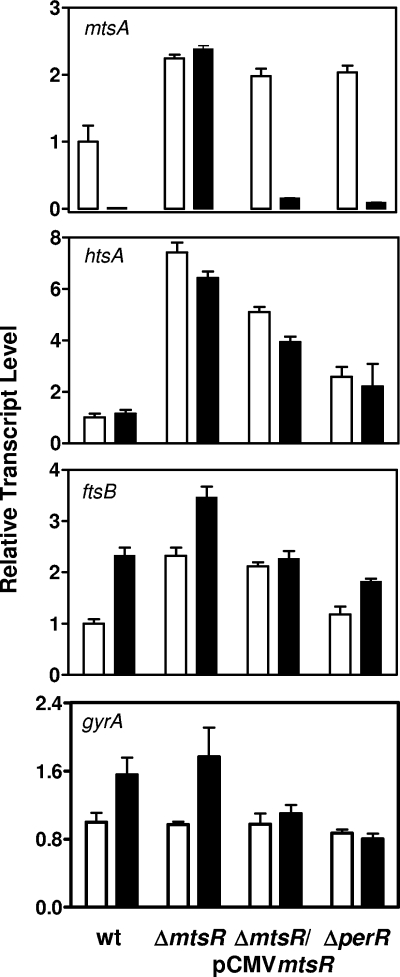

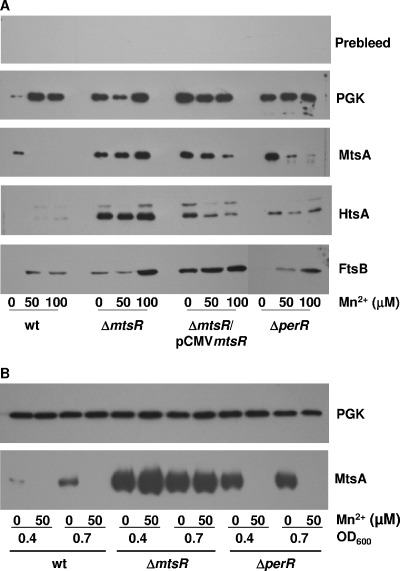

Downregulation of mtsA transcription by MtsR in response to Mn2+.

To test whether MtsR or PerR mediates the Mn2+-dependent repression of mtsA transcription, the mtsR or perR gene was deleted by gene replacement, and the effect of the deletions on mtsA transcription was examined. mtsA transcription is downregulated in the ΔperR mutant strain, but not in the ΔmtsR mutant, in the presence of Mn2+ (Fig. 3), and in trans expression of mtsR from pCMVmtsR restores the response of mtsA transcription to Mn2+ in the ΔmtsR mutant. Consistent with the transcription data, levels of the MtsA protein decreases dramatically in wt and ΔperR strains grown to an OD600 of 0.2 in the presence of 50 or 100 μM Mn2+ but not in the ΔmtsR mutant (Fig. 4A). As expected, Mn2+ also depresses MtsR expression in the wt and ΔperR strains, but not in ΔmtsR strain, at the mid (OD600 = 0.4) and late (OD600 = 0.7) exponential growth phases (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that MtsR, but not PerR, directly regulates mtsA transcription in response to Mn2+.

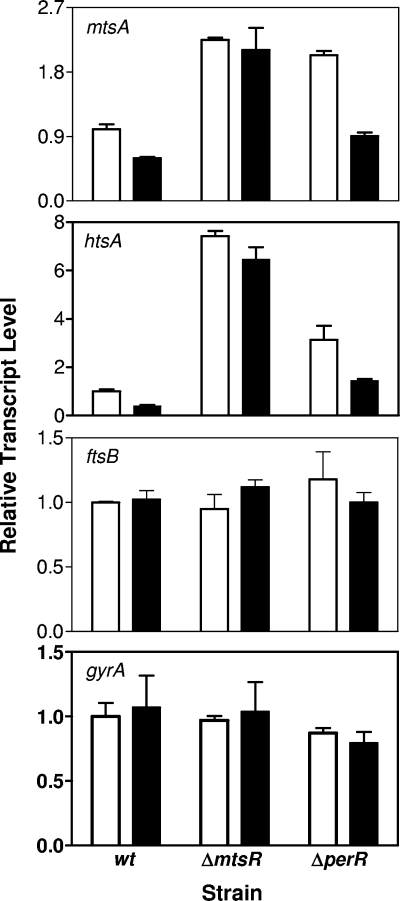

FIG. 3.

Effect of Mn2+ on levels of mtsA, htsA, ftsB, and gyrA (control) transcripts in wt, ΔmtsR, ΔperR, and pCMVmtsR-complemented ΔmtsR (ΔmtsR/pCMVmtsR). Real-time RT-PCR assays were carried out with total RNA isolated from the strains grown to an OD600 of 0.2 in DTHYMg without (□) or with 100 μM MnCl2 (▪). The transcript levels ± the SD of triplicate measurements relative to that of each transcript in wt GAS grown in DTHYMg are shown.

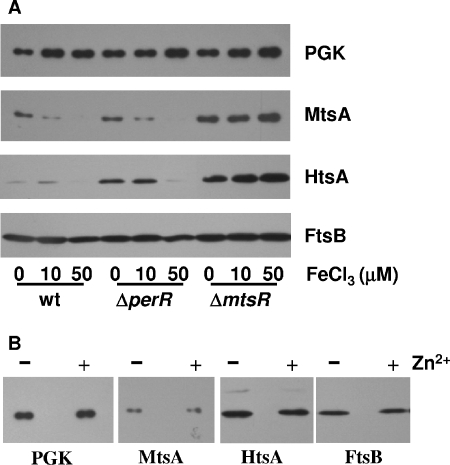

FIG. 4.

Effects of Mn2+ and mtsR and perR deletions on expression of MtsA, HtsA, and FtsB. (A) Western blots showing the effect of Mn2+ on levels of MtsA, HtsA, FtsB, and PGK (control) in wt, ΔmtsR, ΔperR, and ΔmtsR/pCMVmtsR strains. The strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.2 in DTHYMg without or with 50 or 100 μM MnCl2. Proteins from 2 × 106 and 1 × 108 cells were probed with mouse antisera specific to MtsA or PGK and HtsA or FtsB, respectively. The blot using pooled prebleed for MtsA, HtsA, and FtsB immunizations is included to demonstrate the specificity of the antisera. (B) Western blots showing the relative levels of MtsA and PGK (control) in the wt, ΔmtsR, and ΔperR strains grown in DTHYMg without or with 50 μM Mn2+ to the mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.4) and late exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.7). Proteins from 4 × 106 cells were probed for both proteins.

Effect of Fe3+ on mtsA expression.

To examine whether mtsA expression is affected by iron and whether MtsR and/or PerR depresses mtsA expression in response to Fe, the levels of mtsA transcript and MtsA protein were compared by real-time RT-PCR and Western blot analyses, respectively, in the wt, ΔperR, and ΔmtsR strains grown in DTHYMg with 0, 10, and 50 μM FeCl3. Fe3+, instead of Fe2+, was used because Fe2+ would autooxidize to Fe3+ during GAS growth. Western blotting clearly shows the lower levels of MtsA in the wt and ΔperR strains grown in 10 and 50 μM FeCl3 than in strains grown in 0 μM FeCl3, but the expression of MtsA is not depressed by Fe3+ in the ΔmtsR mutant (Fig. 5A) . The downregulation of MtsA expression by Fe3+ was also observed in the wt and ΔperR strains but not in the ΔmtsR mutant at the mid-exponential growth phase (Data not shown). The results of mtsA transcription analysis (Fig. 6) are consistent with the Western blotting results. These results suggest that MtsR also downregulates mtsA expression in response to Fe3+.

FIG. 5.

Western blots showing the effects of Fe3+ (A) and Zn2+ (B) on expression of MtsA, HtsA, FtsB, and PGK (control). The wt, ΔmtsR, and ΔperR strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.2 in DTHYMg without or with 10 μM or 50 μM FeCl3, or the wt strain was grown in DTHYMg without or with 100 μM ZnSO4. The numbers of cells used to probe MtsA and HtsA or FtsB were the same as in Fig. 4.

FIG. 6.

Effect of iron on levels of mtsA, htsA, ftsB, and gyrA (control) transcripts in the wt, ΔmtsR, and ΔperR strains. Real-time RT-PCR assays were carried out with total RNA isolated from the strains grown to an OD600 of 0.2 in DTHYMg without (□) or with 50 μM FeCl3 (▪). The transcript levels ± the SD of triplicate measurements relative to that of each transcript in wt GAS grown in DTHYMg are shown.

Downregulation of htsA expression in response to Fe3+ but not Mn2+.

As assessed by Western blotting analysis, the level of HtsA decreases in wt and ΔperR strains grown in DTHYMg with 50 μM FeCl3 compared to those in the strains grown in DTHYMg without FeCl3 (Fig. 5A). However, no such decrease was observed in the ΔmtsR mutant under the same conditions (Fig. 5A). The levels of htsA transcript in these strains under the same conditions (Fig. 6) are consistent with the levels of HtsA protein. These results suggest that MtsR regulates the expression of htsA in response to Fe levels, confirming the previous finding (2). This interpretation is further supported by the observation that the ΔmtsR strain has much higher levels of htsA transcript (Fig. 3 and 6) and HtsA protein (Fig. 5) than the wt strain. However, Mn2+ does not induce decrease in HtsA expression (Fig. 3 and 4). The HtsA bands of the wt strain in Fig. 3 are barely visible only in the presence of Mn2+ under the conditions used, and the visible HtsA expression pattern (data not shown) obtained at higher sample loading is very similar to the expression pattern of the control protein PGK of the wt strain. This pattern is repeatable and, thus, is unlikely due to protein loading. A possible reason for this pattern is that growth of the wt strain is slower in the presence of Mn2+ than in the absence of Mn2+, presumably resulting in protein accumulation. The transcript levels of htsA under these conditions (Fig. 3) support this explanation. These results suggest that MtsR differentially regulates the expression of mtsA and htsA.

MtsR and PerR do not regulate ftsB expression.

FtsABCD transports ferric ferrichrome (8), and thus its expression should be regulated by intracellular Fe levels. However, FeCl3 in DTHYMg did not affect the levels of FtsB in the wt, ΔperR, or ΔmtsR strain (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that MtsR and PerR do not regulate the expression of ftsABCD. Like the expression pattern of HtsA in the wt strain as a function of Mn2+ supplementation, the levels of FtsB in the wt strain increase in the presence of Mn2+. However, unlike the HtsA expression, the same pattern of FtsB expression is also obvious in the other strains (Fig. 4). The comparison of the expression patterns of FtsB and PGK in the mutant strains (Fig. 4) and transcription data (Fig. 3) suggest that protein loading is not the primary reason for the FtsB expression pattern. The reason for the enhancement of FtsB expression by Mn2+ is unknown.

Zn2+ does not induce change in expression of mtsA, htsA, and ftsB.

Previous works (13) suggest that MtsABC may transport Zn2+. If this is true, Zn2+ in growth medium should affect mtsA expression. To test this idea, levels of mtsA transcript and MtsA protein were assessed in the wt strain grown in DTHYMg with or without 100 μM ZnSO4. There was no significant difference in the levels of MtsA (Fig. 5B) and mtsA transcript (data not shown). Furthermore, Zn2+ had no effect on expression of HtsA and FtsB (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that MtsR and PerR do not regulate the expression of mtsA, htsA, and ftsB in response to Zn2+.

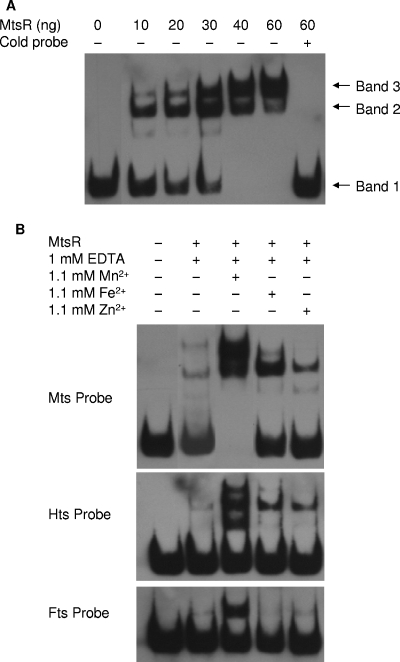

Binding of MtsR to the mts promoter region.

The binding of MtsR to the mtsA promoter region was examined by EMSA using biotin-labeled mts promoter probe. In the presence of 0 to 60 ng or 0 to 1.2 μM MtsR and 100 μM Mn2+, the probe in gel electrophoresis shifts from the location without MtsR (band 1 in Fig. 7A) in a dose-dependent manner, and the unlabeled probe completely prevents the shifting (Fig. 7A), suggesting that MtsR specifically binds to the probe. There are two probe-MtsR complex species in the presence of 10 ng of MtsR. As MtsR concentration increases, the intensity of the dominant band with higher mobility (band 2 in Fig. 7A) first increases and then decreases, and the other band with slower mobility (band 3) gradually becomes dominant. These observations can be explained by assuming the presence of two MtsR-binding sites on the probe, which have different affinities. Apparently, the site with higher affinity is loaded with MtsR at the lower MtsR concentrations, resulting in band 2, and both sites have bound MtsR in band 3 at the higher MtsR concentrations. The binding requires Mn2+ (Fig. 7B). When Mn2+ was replaced with Fe2+, MtsR appears to bind to one site with an affinity lower than that for MtsR/Mn2+ complexes. Zn2+ cannot promote strong MtsR binding.

FIG. 7.

EMSA assessing the binding of MtsR to the promoter regions of mtsABC, htsABC, and ftsABCD. The assay was performed as described in the text. (A) Dose-dependent binding of MtsR to the promoter probe of mtsABC. The biotin-labeled probe (0.4 pmol) was incubated with MtsR at the indicated concentrations with or without the nonlabeled probe. (B) Comparison of MtsR binding to the promoter probes of mtsABC, htsABC, and ftsABCD in the presence of Mn2+, Fe2+, or Zn2+. MtsR (60 ng) was incubated with each probe in the presence of 1.0 mM EDTA and 1.1 mM Mn2+, Fe2+, or Zn2+.

The binding of MtsR to the hts promoter region has been described (2). We also detected MtsR binding to the hts promoter probe. We did not attempt to optimize conditions to repeat the detailed characterization of the binding but just compared the relative affinity of the mts and hts probes for MtsR. Under the conditions we used, MtsR binds to the mts probe stronger than the htsA probe in the presence of Mn2+ or Fe2+ (Fig. 7B). We did not detect the binding of MtsR binding to the fts probe in the presence of Fe2+ or Zn2+, though a shifted band was detected in the presence of Mn2+. Taken together, the gel shift data support the gene expression data described above.

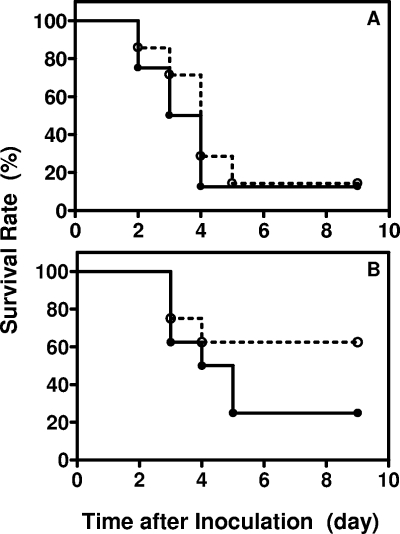

Virulence of the ΔmtsR mutant.

To examine effect of the mtsR deletion on GAS virulence, groups of seven CD-1 Swiss mice were infected subcutaneously with 1.0 × 108 CFU wt or 9 × 107 CFU ΔmtsR strain, and the mouse survival rates of the groups were monitored daily for 9 days. The ΔmtsR infection at the same dose was repeated with eight mice. The mutant did not show significant difference in virulence from the wt strain in both tests (P = 0.6751 and 0.5277 [log-rank test] for the first and second tests, respectively). The combined survival rate of the two experiments with the mutant versus that of the control group had a P value of 0.9093 (Fig. 8A). The experiment was then repeated with 5 × 107 CFU wt and 4.6 × 107 CFU mutant strains. Five of the eight mice infected with the wt strain survived, while six of eight mice infected with the mutant strain died (Fig. 8B). It appears that the mutant is more virulent. However, the difference in survival rate is not statistically significant (P = 0.2040). Thus, the mtsR deletion does not affect virulence significantly in the mouse model of subcutaneous GAS infection.

FIG. 8.

Comparison of wt and ΔmtsR mutant strain virulence. (A) Groups of seven female CD-1 mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 1.0 × 108 CFU wt strain (○) or 9.2 × 107 CFU ΔmtsR strain (•), and the survival rates were determined daily. The infection with the mutant was repeated with eight mice, and the survival rate presented for the mutant is the combined result of the two challenges (P = 0.9093 [log-rank test]). (B) Survival curves of mice infected with a lower bacteria dose. Groups of eight female CD-1 mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 5.0 × 107 CFU wt strain (○) or 4.7 × 107 CFU ΔmtsR strain (•). P = 0.2040.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the roles of the metalloregulators and metal ions in regulation of the expression of mtsABC, htsABC, and ftsABCD. The major finding is that MtsR regulates the expression of both mtsABC and htsABC with similar responses to Fe but different responses to Mn2+. In addition, PerR is not directly involved in the regulation of these transporters in response to Mn2+, Fe3+, and Zn2+, MtsR does not regulate FtsABCD, nor does Zn2+ affect the expression of the transporters. MtsR binds to the mts promoter region in the presence of Mn2+ or Fe2+. MtsR is not important for GAS virulence in the mouse model of subcutaneous infection.

The levels of mtsA transcript and MtsA protein are dramatically downregulated in the presence of Mn2+, and the mtsR deletion abolishes the Mn2+-induced downregulation of mtsA expression. in trans expression of mtsR in the ΔmtsR mutant restores the depression of mtsA transcription by Mn2+. These results support the conclusion that MtsR regulates the expression of MtsABC in response to Mn2+. Expression of htsA also decreases at both transcript and protein levels in response to the addition of FeCl3 in growth media, and this downregulation is abolished in the ΔmtsR mutant, suggesting that MtsR is a negative transcriptional regulator of HtsABC in response to Fe. The data confirm a recent finding that MtsR is involved in regulation of htsABC (2). Thus, MtsR regulates the expression of both mtsABC and htsABC. To our knowledge, MtsR is the first metalloregulator of the Fur and DtxR families to be shown to control the expression of two transporters involved in acquisition of iron and other metal ion.

A striking feature of the MtsR-mediated regulation is the differential metal ion specificity in its regulation of mtsA and htsA. Although MtsR depresses the expression of both mtsA and htsA in response to FeCl3, it mediates the Mn2+-induced depression of mtsA expression. However, Mn2+ does not induce the downregulation of HtsA expression. HtsABC takes up heme (18, 20, 24), and MtsABC is involved in the acquisition of Fe3+ and Mn2+ (14). Apparently, MtsR can differentially regulate the expression of mtsABC and htsABC according to their functions. It has been known that some metalloregulators are specific to both Fe and Mn (11). However, MtsR is unique in that it responds to both Fe3+ and Mn2+ in regulation of one transporter, while it responds to only Fe3+ in regulation of another transporter.

It has been reported that MtsR binds to the promoter region of HtsABC (2). We found that MtsR binds more strongly to the mts promoter region than to the hts promoter region. These findings correlate well with the more robust control of mtsA expression than of htsA expression by MtsR. The gel shifting data suggest that the mts promoter region has two binding sites with different affinities for MtsR. MtsR/Mn2+ seems to bind to both sites, whereas MtsR/Fe2+ binds to one site with an affinity that is weaker than those for MtsR/Mn2+ binding. The difference in affinity and specificity of MtsR/Mn2+ and MtsR/Fe2+ for DNA binding might be the basis of the differential regulation of mtsA and htsA expression by MtsR. We plan to test this idea in the follow-up study.

PerR, a widely distributed metalloregulator, responds to metal ion and peroxide stress. GAS PerR is involved in peroxide resistance as a repressor by regulating transcription of mrgA encoding a peroxide resistance protein (5). It has been reported that a GAS perR-deficient mutant showed reduced levels of mtsA transcript compared to its parent strain, and the authors of that study suggested that PerR functions as an enhancer of mtsABC transcription (27). This is in contrast to the usual PerR function as a metal-dependent repressor. Although we did not observe a decrease in the levels of mtsA transcript and MtsA protein in the ΔperR mutant compared to the wt strain, our data suggest that PerR is not a Mn-, Fe-, and Zn-dependent repressor that regulates the expression of the three transporters. It appears that htsA is expressed at higher levels in the ΔperR mutant than in the wt strain. However, htsA expression in the ΔmtsR mutant does not respond to Fe3+, suggesting that PerR does not directly regulate htsABC.

FtsABCD is involved in the uptake of ferric ferrichrome, and inactivation of mtsA or htsA enhances expression of FtsABCD (8). Surprisingly, FeCl3 had no effect on ftsB expression, nor do MtsR and PerR regulate the expression of ftsB. GAS is not known to produce siderophores, and GAS genomes do not have genes encoding homologues of siderophore production systems. Siderophore production was not detected in GAS (8). Furthermore, the expression levels of FtsABCD are not high (8, 18). FtsABCD may not be a major transporter for iron acquisition and, thus, may not be regulated stringently. Alternatively, there is another regulator for the regulation of ftsABCD expression.

MtsA binds Zn2+, and the association of Zn with an mtsA-deficient mutant is 60% of that with its parent strain (13). It is not clear whether the decrease is due to the decreased uptake or the loss of Zn binding. MtsA is a highly expressed extracellular protein, and the decrease is likely due to the loss of Zn binding to MtsA because of the absence of MtsA in the mutant. This likelihood is supported by our data that high levels of Zn2+ in medium have no negative effect on mtsA expression. Thus, MtsABC may not be involved in Zn2+ uptake.

It has been reported that the mtsR inactivation in a serotype M49 GAS strain attenuates its virulence in a zebra fish model of GAS infection (2). Another report (4) proposed that a natural inactivation mutation of mtsR in an M3 strain contributes to its milder virulence compared to other M3 strains isolated from invasive infections. However, the mtsR deletion in MGAS 5005, a highly virulent serotype M1 strain isolated from a patient with severe invasive GAS infection, does not significantly affect its virulence in the mouse model of subcutaneous infection. Our data suggest that the M49 strains and mtsR mutants of the virulent M3 strains should be tested in animal models, which mimic GAS infections in humans, to conclude whether MtsR is important for virulence of these strains.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants P20 RR-020185 and P20 RR-16455 from the National Center for Research Resources, grant K22 AI057347 from the National Institutes of Health, and the Montana State University Agricultural Experimental Station.

Editor: F. C. Fang

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando, M., Y. C. Manabe, P. J. Converse, E. Miyazaki, R. Harrison, J. R. Murphy, and W. R. Bishai. 2003. Characterization of the role of the divalent metal ion-dependent transcriptional repressor MntR in the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 71:2584-2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates, C. S., C. Toukoi, M. N. Neely, and Z. Eichenbaum. 2005. Characterization of MtsR, a new metal regulator in group a Streptococcus, involved in iron acquisition and virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:5743-5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates, C. S., G. E. Montanez, C. R. Woods, R. M. Vincent, and Z. Eichenbaum. 2003. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes operon involved in binding of hemoproteins and acquisition of iron. Infect. Immun. 71:1042-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beres, S. B., E. W. Richter, M. J. Nagiec, P. Sumby, S. F. Porcella, F. R. DeLeo, and J. M. Musser. 2006. Molecular genetic anatomy of inter- and intraserotype variation in the human bacterial pathogen group A Streptococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:7059-7064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenot, A., K. Y. King, and M. G. Caparon. 2005. The PerR regulon in peroxide resistance and virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 55:221-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz-Mireles, E., M. Wexler, G. Sawers, D. Bellini, J. D. Todd, and A. W. Johnston. 2004. The Fur-like protein Mur of Rhizobium leguminosarum is a Mn2+-responsive transcriptional regulator. Microbiology 150:1447-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanks, T. S., M. Liu, M. J. Mclure, and B. Lei. 2005. ABC transporter FtsABC of Streptococcus pyogenes mediates uptake of ferric ferrichrome. BMC Microbiology 5:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hantke, K. 2001. Iron and metal regulation in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hantke, K. 2005. Bacterial zinc uptake and regulators. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:196-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill, P. J., A. Cockayne, P. Landers, J. A. Morrissey, C. M. Sims, and P. Williams. 1998. SirR, a novel iron-dependent repressor in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 66:4123-4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoe, N. P., K. Nakashima, D. Grigsby, X. Pan, S. J. Dou, S. Naidich, M. Garcia, E. Kahn, D. Bergmire-Sweat, and J. M. Musser. 1999. Rapid molecular genetic subtyping of serotype M1 group A Streptococcus strains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:254-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janulczyk, R., J. Pallon, and L. Bjorck. 1999. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes ABC transporter with multiple specificity for metal cations. Mol. Microbiol. 34:596-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janulczyk, R., S. Ricci, and L. Bjorck. 2003. MtsABC is important for manganese and iron transport, oxidative stress resistance, and virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 71:2656-2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King, K. Y., J. A. Horenstein, and M. G. Caparon. 2002. Aerotolerance and peroxide resistance in peroxidase and PerR mutants of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 182:5290-5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei, B., S. Mackie, S. Lukomski, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A Streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:6807-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei, B., L. M. Smoot, H. Menning, J. M. Voyich, S. V. Kala, F. R. Deleo, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Identification and characterization of a novel heme-associated cell-surface protein made by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:4494-4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei, B., M. Liu, J. M. Voyich, C. I. Prater, S. V. Kala, F. R. DeLeo, and J. M. Musser. 2003. Identification and characterization of HtsA, a second heme-binding protein made by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 71:5962-5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei, B., M. Liu, G. Chesney, and J. M. Musser. 2004. Extracellular putative lipoproteins made by Streptococcus pyogenes: identification of new potential vaccine candidate antigens. J. Infect. Dis. 189:79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, M., and B. Lei. 2005. Heme transfer from streptococcal cell-surface protein Shp to HtsA of transporter HtsABC. Infect. Immun. 73:5086-5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, M., T. S. Hanks, J. Zhang, M. J. McClure, D. W. Siemsen, J. L. Elser, M. T. Quinn, and B. Lei. 2006. Defects in ex vivo and in vivo growth and sensitivity to osmotic stress of group A Streptococcus caused by interruption of response regulator gene vicR. Microbiology 152:967-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mongkolsuk, S., and J. D. Helmann. 2002. Regulation of inducible peroxide stress responses. Mol. Microbiol. 45:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrissey, J. A., A. Cockayne, K. Brummell, and P. Williams. 2004. The staphylococcal ferritins are differentially regulated in response to iron and manganese and via PerR and Fur. Infect. Immun. 72:972-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nygaard, T. K., G. C. Blouin, M. Liu, M. Fukumura, J. S. Olson, M. Fabian, D. M. Dooley, and B. Lei. 2006. The mechanism of direct heme transfer from the streptococcal cell surface protein Shp to HtsA of the HtsABC transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 281:20761-20771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Paik, S., A. Brown, C. L. Munro, C. N. Cornelissen, and T. Kitten. 2003. The sloABCR operon of Streptococcus mutans encodes an Mn and Fe transport system required for endocarditis virulence and its Mn-dependent repressor. J. Bacteriol. 185:5967-5975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Posey, J. E., J. M. Hardham, S. J. Norris, and F. C. Gherardini. 1999. Characterization of a manganese-dependent regulatory protein, TroR, from Treponema pallidum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10887-10892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci, S., R. Janulczyk, and L. Bjorck. 2002. The regulator PerR is involved in oxidative stress response and iron homeostasis and is necessary for full virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:4968-4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt, M. P., M. Predich, L. Doukhan, I. Smith, and R. K. Holmes. 1995. Characterization of an iron-dependent regulatory protein (IdeR) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a functional homolog of the diphtheria toxin repressor (DtxR) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Infect. Immun. 63:4284-4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao, X., N. Schiering, H. Y. Zeng, D. Ringe, and J. R. Murphy. 1994. Iron, DtxR, and the regulation of diphtheria toxin expression. Mol. Microbiol. 14:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yakhnin, H., and P. Babitzke. 2004. Gene replacement method for determining conditions in which Bacillus subtilis genes are essential or dispensable for cell viability. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64:382-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]