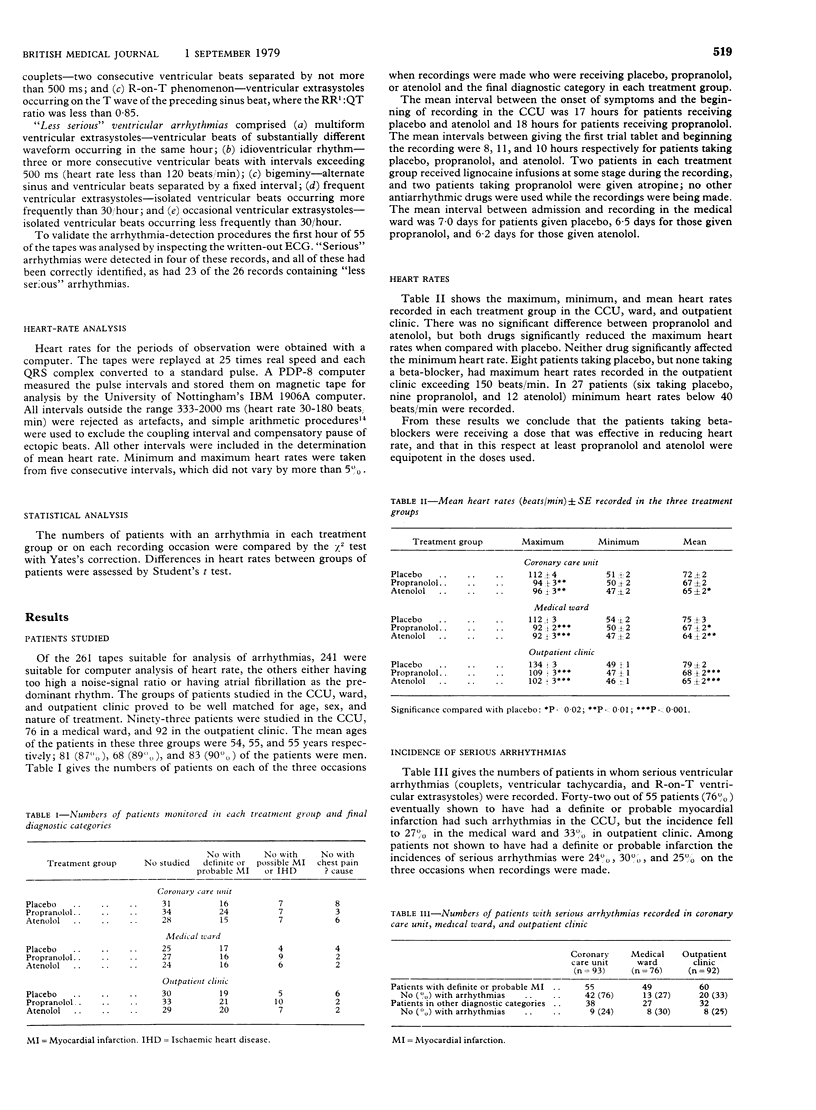

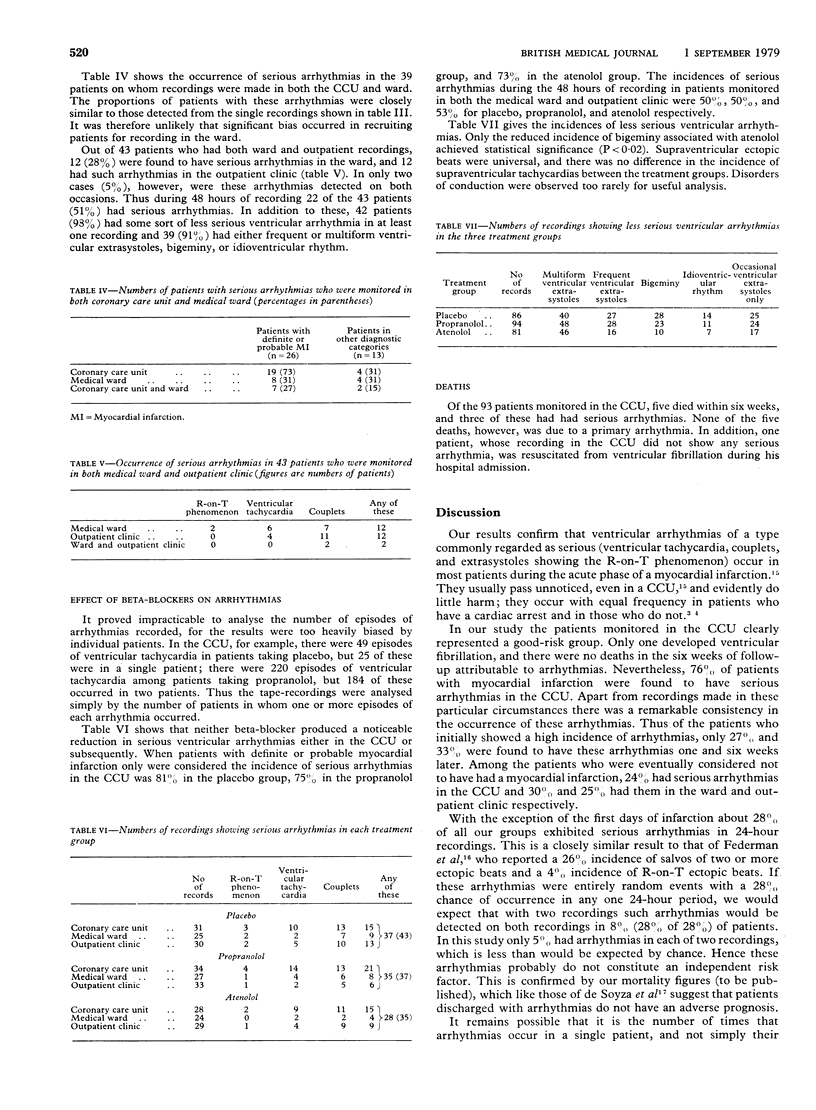

Abstract

Twenty-four-hour electrocardiographic tape-recording was used to investigate the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with suspected myocardial infarction who were receiving either propranolol, atenolol, or placebo. Recordings begun within 24 hours after admission to a coronary care unit showed that 76% of patients eventually found to have had a myocardial infarction had ventricular arrhythmias of a type generally regarded as serious, whereas of patients in whom myocardial infarction was not substantiated, only 24% had such arrhythmias. At one and six weeks after admission the incidence of arrhythmias ranged from 25% to 33% irrespective of diagnosis. Of patients monitored at both one and six weeks, however, only 5% had arrhythmias on each occasion. Patients treated with propranolol and atenolol showed a similar incidence of arrhythmias to those taking placebo. There was no difference in the incidence or type of arrhythmias recorded between patients who died and those who were still alive at six weeks.

These results confirm that “serious” ventricular arrythmias occur in most patients during the acute phase of myocardial infarction and suggest that they do not constitute an independent risk factor. Beta-blockers showed little evidence of useful antiarrhythmic action in the dosage used, but increasing the dosage in suspected myocardial infarction is not practicable because of the risk of hypotension. The findings raise grave doubts about the value of studying arrhythmias to assess drugs intended to reduce mortality from myocardial infarction.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Briant R. B., Norris R. M. Alprenolol in acute myocardial infarction: Double-blind trial. N Z Med J. 1970 Mar;71(454):135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J. M., Hamer J., Shelton J. R., Taylor S., Venning G. R. The rhythm of the normal human heart. Lancet. 1976 Sep 4;1(7984):508–512. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen J., Felsby M., Jorgensen F. S., Nielsen B. L., Roin J., Strange B. Absence of prophylactic effect of propranolol in myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1966 Oct 29;2(7470):920–924. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)90533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sherif N., Myerburg R. J., Scherlag B. J., Befeler B., Aranda J. M., Castellanos A., Lazzara R. Electrocardiographic antecedents of primary ventricular fibrillation. Value of the R-on-T phenomenon in myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1976 Apr;38(4):415–422. doi: 10.1136/hrt.38.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federman J., Whitford J. A., Anderson S. T., Pitt A. Incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in first year after myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1978 Nov;40(11):1243–1250. doi: 10.1136/hrt.40.11.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fentem P. H., Fitton D. L., Hampton J. R., Hayward R. A., Willmott J. N. A method for counting ectopic beats by computer analysis of R-R intervals. Eur J Cardiol. 1977 Jan;5(1):29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman W. H., Weksler B., Christodoulou J. P., Smithen C., Killip T. Reversal of abnormal platelet aggregability and change in exercise tolerance in patients with angina pectoris following oral propranolol. Circulation. 1974 Nov;50(5):887–896. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.50.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown B., Fakhro A. M., Hood W. B., Jr, Thorn G. W. The coronary care unit. New perspectives and directions. JAMA. 1967 Jan 16;199(3):188–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown B., Wolf M. Approaches to sudden death from coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1971 Jul;44(1):130–142. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris R. M., Caughey D. E., Scott P. J. Trial of propranolol in acute myocardial infarction. Br Med J. 1968 May 18;2(5602):398–400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5602.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romhilt D. W., Bloomfield S. S., Chou T. C., Fowler N. O. Unreliability of conventional electrocardiographic monitoring for arrhythmia detection in coronary care units. Am J Cardiol. 1973 Apr;31(4):457–461. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)90294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow P. J. Effect of propranolol in myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1965 Sep 18;2(7412):551–553. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(65)90863-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Soyza N., Bennett F. A., Murphy M. L., Bissett J. K., Kane J. J. The relationship of paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia complicating the acute phase and ventricular arrhythmia during the late hospital phase of myocardial infarction to long-term survival. Am J Med. 1978 Mar;64(3):377–381. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]