Abstract

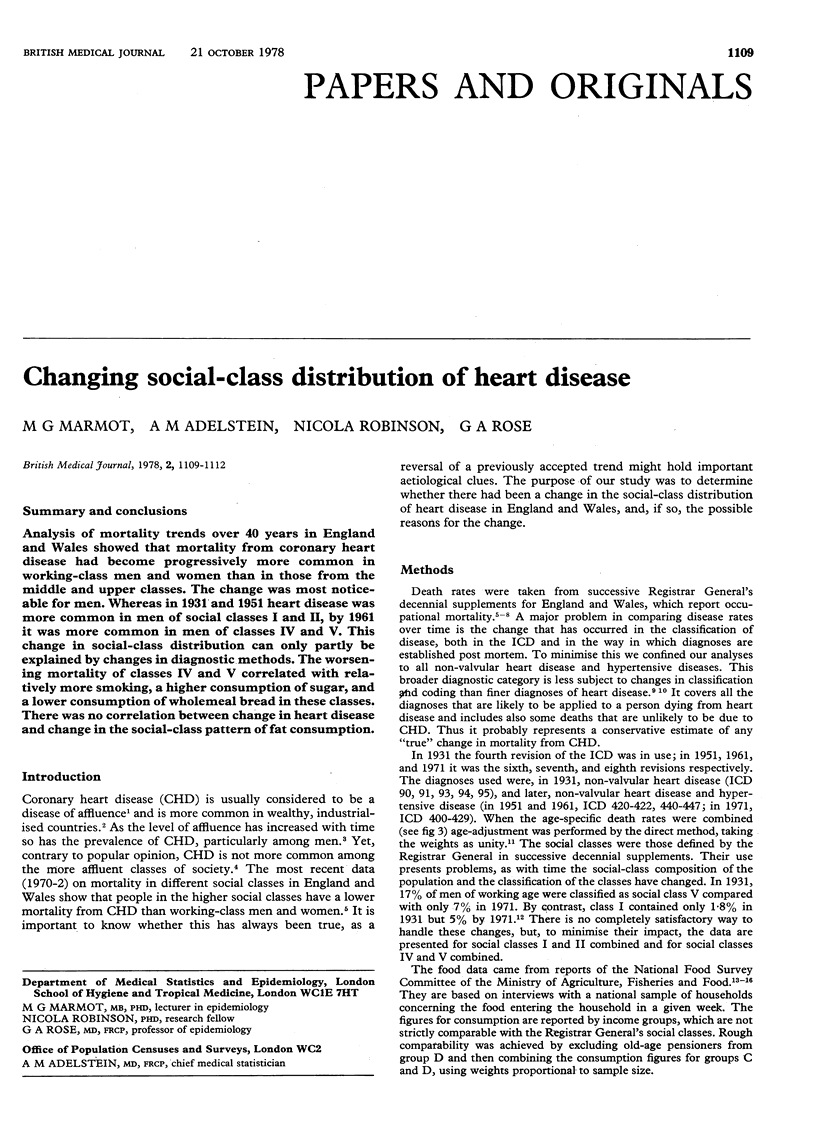

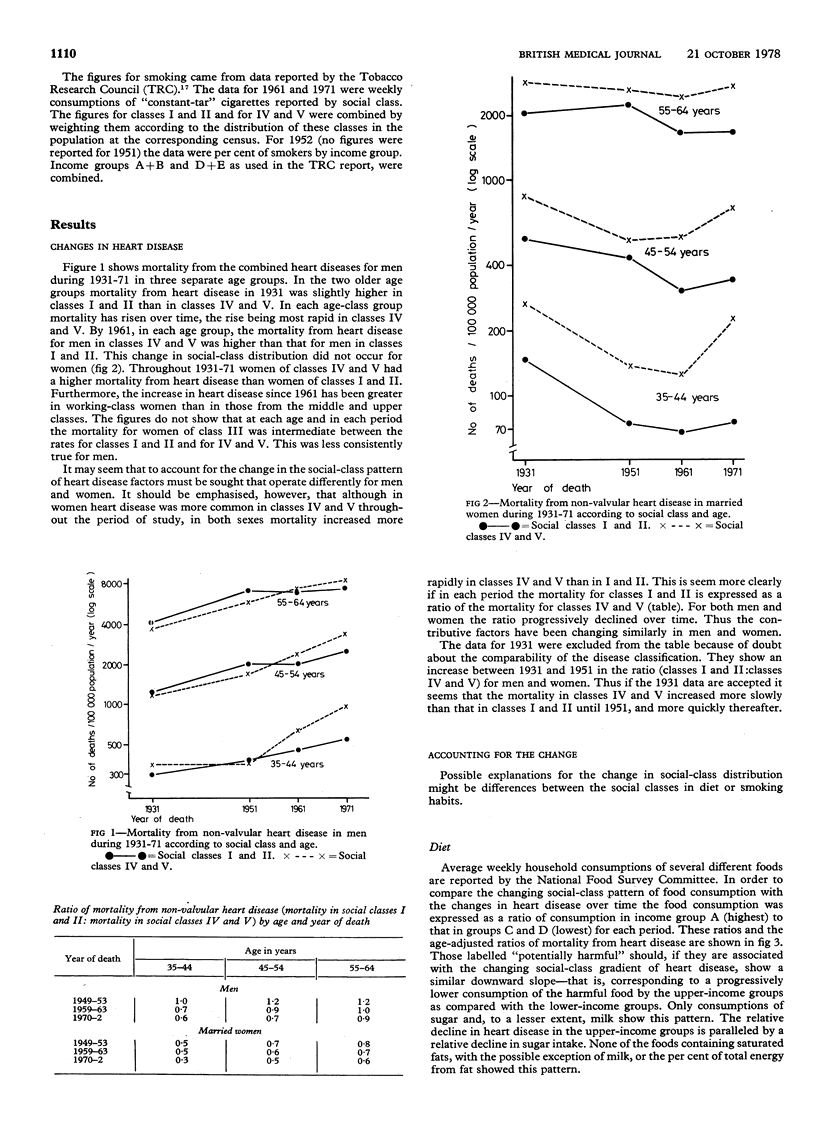

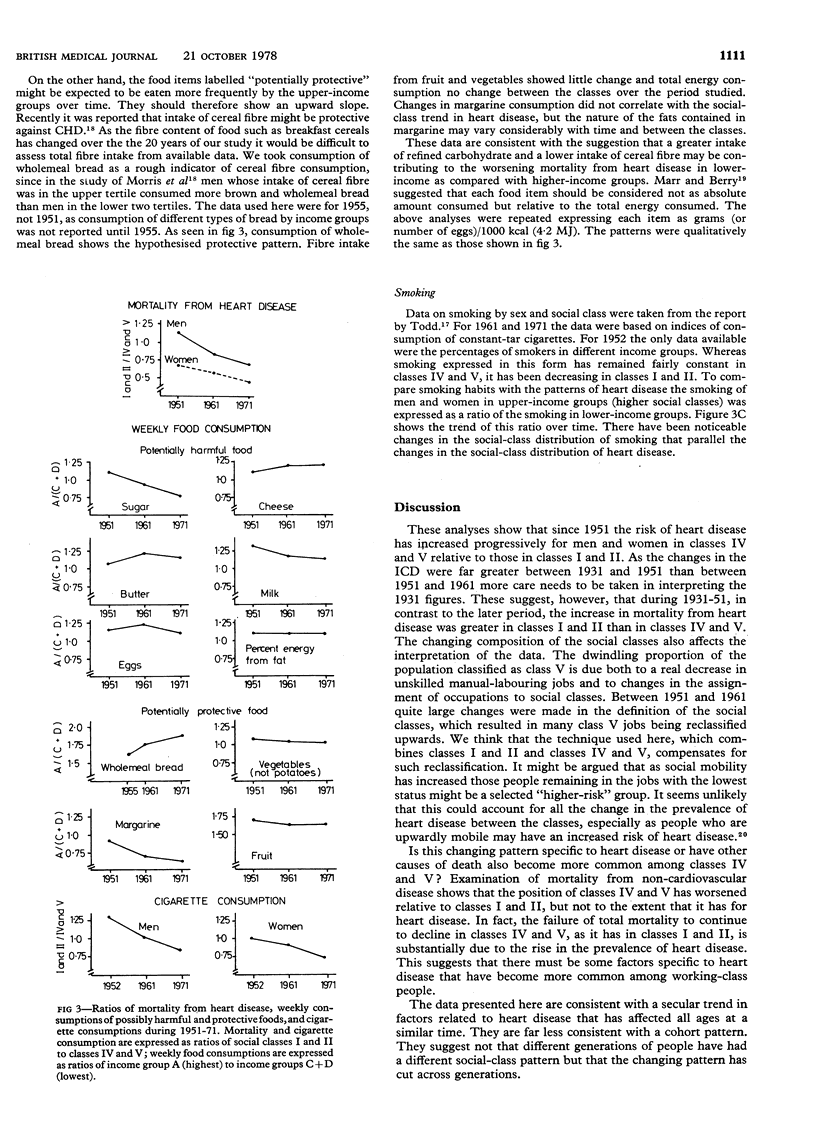

Analysis of mortality trends over 40 years in England and Wales showed that mortality from coronary heart disease had become progressively more common in working-class men and women than in those from the middle and upper classes. The change was most noticeable for men. Whereas in 1931 and 1951 heart disease was more common in men of social classes I and II, by 1961 it was more common in men of classes IV and V. This change in social-class distribution can only partly be explained by changes in diagnostic methods. The worsening mortality of classes IV and V correlated with relatively more smoking, a higher consumption of sugar, and a lower consumption of wholemeal bread in these classes. There was no correlation between change in heart disease and change in the social-class pattern of fat consumption.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antonovsky A. Social class and the major cardiovascular diseases. J Chronic Dis. 1968 May;21(2):65–106. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(68)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beral V. Cardiovascular-disease mortality trends and oral-contraceptive use in young women. Lancet. 1976 Nov 13;2(7994):1047–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90966-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R., Peto R. Mortality in relation to smoking: 20 years' observations on male British doctors. Br Med J. 1976 Dec 25;2(6051):1525–1536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6051.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A. Coronary heart disease--the global picture. Atherosclerosis. 1975 Sep-Oct;22(2):149–192. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(75)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Marr J. W., Clayton D. G. Diet and heart: a postscript. Br Med J. 1977 Nov 19;2(6098):1307–1314. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6098.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUSSER M., STEIN Z. Civilisation and peptic ulcer. Lancet. 1962 Jan 20;1(7221):115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme S. L., Hyman M. M., Enterline P. E. Some social and cultural factors associated with the occurrence of coronary heart disease. J Chronic Dis. 1964 Mar;17(3):277–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YERUSHALMY J. A mortality index for use in place of the age-adjusted death rate. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951 Aug;41(8 Pt 1):907–922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.41.8_pt_1.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YUDKIN J. Diet and coronary thrombosis hypothesis and fact. Lancet. 1957 Jul 27;273(6987):155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(57)90614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du V Florey C., Melia R. J., Darby S. C. Changing mortality from ischaemic heart disease in Great Britain 1968-76. Br Med J. 1978 Mar 11;1(6113):635–637. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6113.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]