Abstract

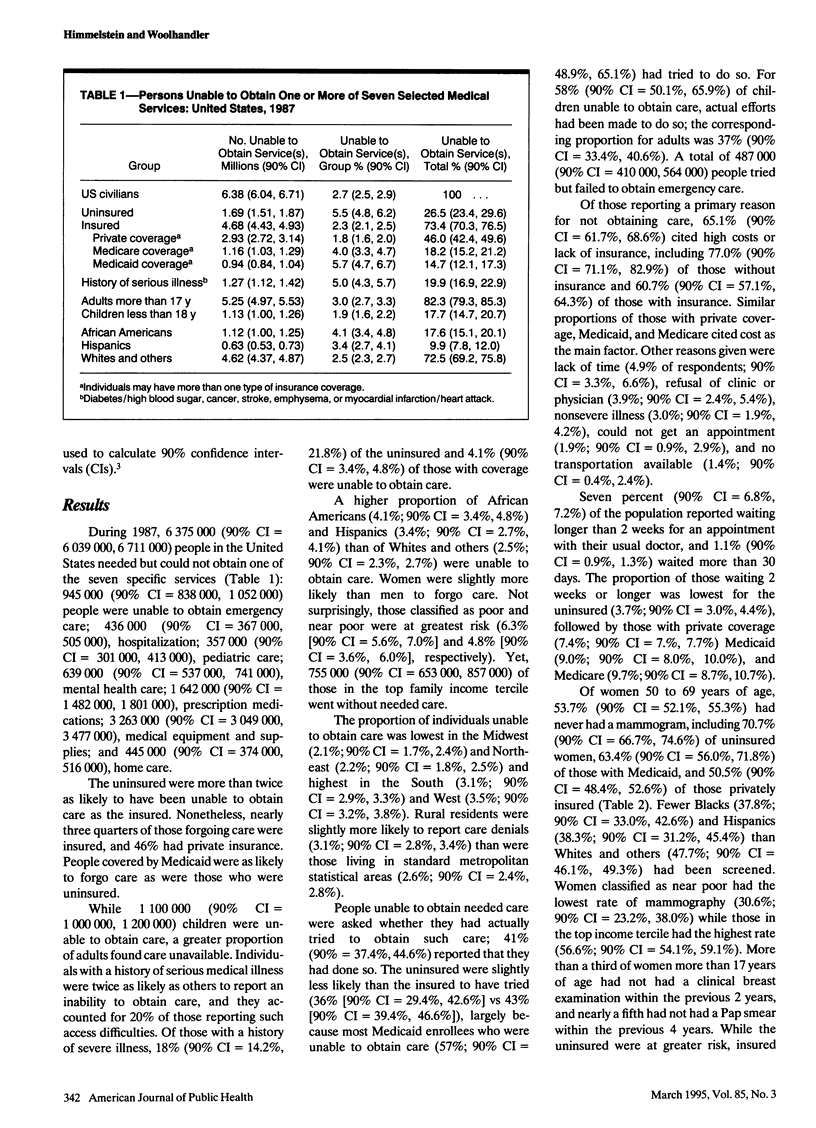

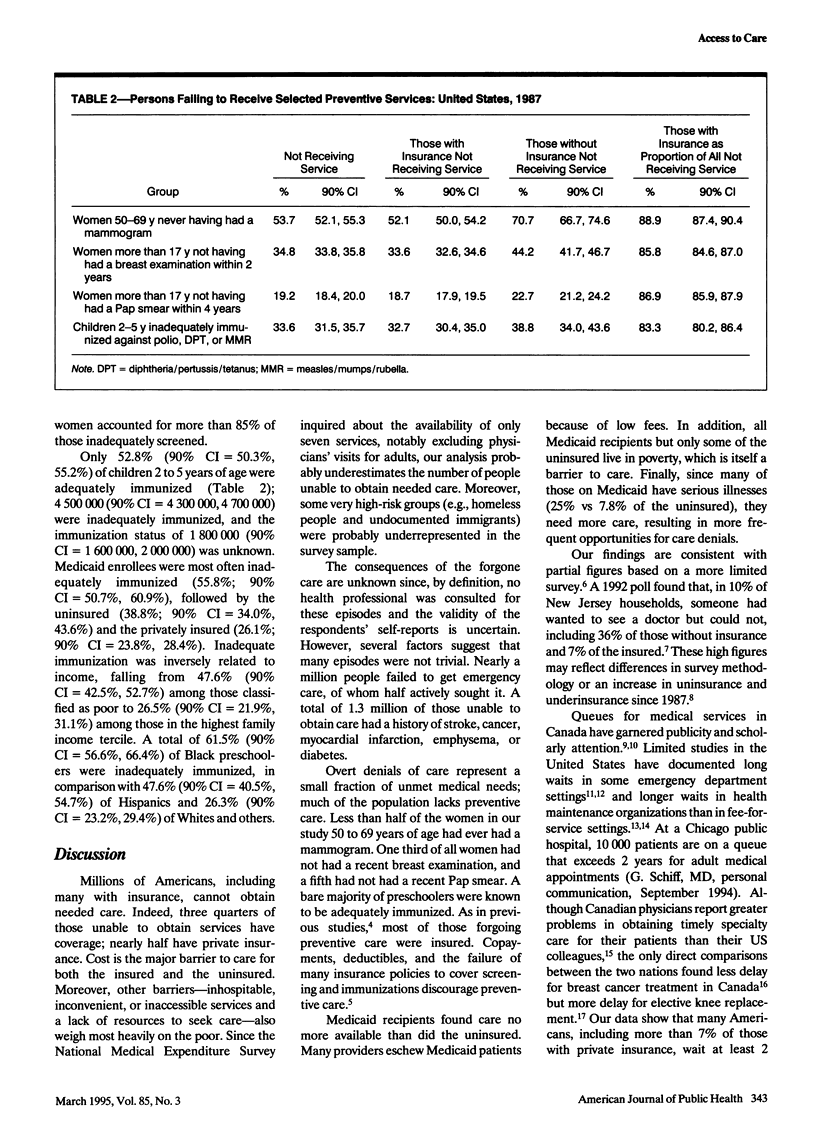

OBJECTIVES. This study analyzed data on US residents reporting that they were unable to obtain needed care. Inadequately immunized children and women inadequately screened for breast or cervical cancer were also examined. METHODS. Data from the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey was analyzed. RESULTS. A total of 6,375,000 (90% confidence interval [CI] = 6,039,000, 6,711,000) people could not get hospitalization, prescription medications, medical equipment/supplies, or emergency, pediatric, mental health, or home care. Although the uninsured were more likely to forego care unavailable, three quarters of those unable to obtain services were insured, and 46% (90% CI = 42.4%, 49.6%) had private coverage. Of those reporting the reason why they failed to obtain care, 65.1% (90% CI = 61.7%, 68.6%) listed high costs or lack of insurance, including 60.7% (90% CI = 57.1%, 64.3%) of the privately insured. More than a third of women had not had a breast examination in the previous 2 years, a fifth had not had a Pap smear within the previous 4 years, and half had never had a mammogram (ages 50-69 only). Of children 2 to 5 years old, 35.1% (90% CI = 31.5%, 35.7%) were inadequately immunized. Medicaid recipients had measures of access to care similar to those of the uninsured. CONCLUSIONS. Many US residents--most of whom have insurance--are unable to obtain needed care, usually because of high costs.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andrulis D. P., Kellermann A., Hintz E. A., Hackman B. B., Weslowski V. B. Emergency departments and crowding in United States teaching hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 1991 Sep;20(9):980–986. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82976-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindman A. B., Grumbach K., Keane D., Rauch L., Luce J. M. Consequences of queuing for care at a public hospital emergency department. JAMA. 1991 Aug 28;266(8):1091–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon R. J., Donelan K., Leitman R., Epstein A., Cantor J. C., Cohen A. B., Morrison I., Moloney T., Koeck C. Health reform lessons learned from physicians in three nations. Health Aff (Millwood) 1993 Fall;12(3):194–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T. Underinsurance in America. N Engl J Med. 1992 Jul 23;327(4):274–278. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207233270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyte P. C., Wright J. G., Hawker G. A., Bombardier C., Dittus R. S., Paul J. E., Freund D. A., Ho E. Waiting times for knee-replacement surgery in the United States and Ontario. N Engl J Med. 1994 Oct 20;331(16):1068–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410203311607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. R., Ware J. E., Jr, Brook R. H., Peterson J. R., Newhouse J. P. Consumer acceptance of prepaid and fee-for-service medical care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Serv Res. 1986 Aug;21(3):429–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward R. A., Shapiro M. F., Freeman H. E., Corey C. R. Inequities in health services among insured Americans. Do working-age adults have less access to medical care than the elderly? N Engl J Med. 1988 Jun 9;318(23):1507–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806093182305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein D. U., Woolhandler S., Wolfe S. M. The vanishing health care safety net: new data on uninsured Americans. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):381–396. doi: 10.2190/5FBA-VEKK-K2DK-JF8V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. J., Hislop T. G., Thomas D. B., Larson E. B. Delay from symptom to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in Washington State and British Columbia. Med Care. 1993 Mar;31(3):264–268. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N., Manning W. G., Peterson C., Goldberg G. A., Phelps C. A., Lillard L. Preventive care: do we practice what we preach? Am J Public Health. 1987 Jul;77(7):801–804. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.7.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A. L., Roos L. L., Brazauskas R., Bedard D. Managing scarce services. A waiting list approach to cardiac catheterization. Med Care. 1990 Sep;28(9):784–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor C. D. A different view of queues in Ontario. Health Aff (Millwood) 1991 Fall;10(3):110–128. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.10.3.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. C. Immunization coverage among preschool children: the United States and selected European countries. Pediatrics. 1990 Dec;86(6 Pt 2):1052–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky F. D., Marder W. D. Waiting to see the doctor. The impact of organizational structure on medical practice. Med Care. 1983 May;21(5):531–542. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhandler S., Himmelstein D. U. Reverse targeting of preventive care due to lack of health insurance. JAMA. 1988 May 20;259(19):2872–2874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]