Abstract

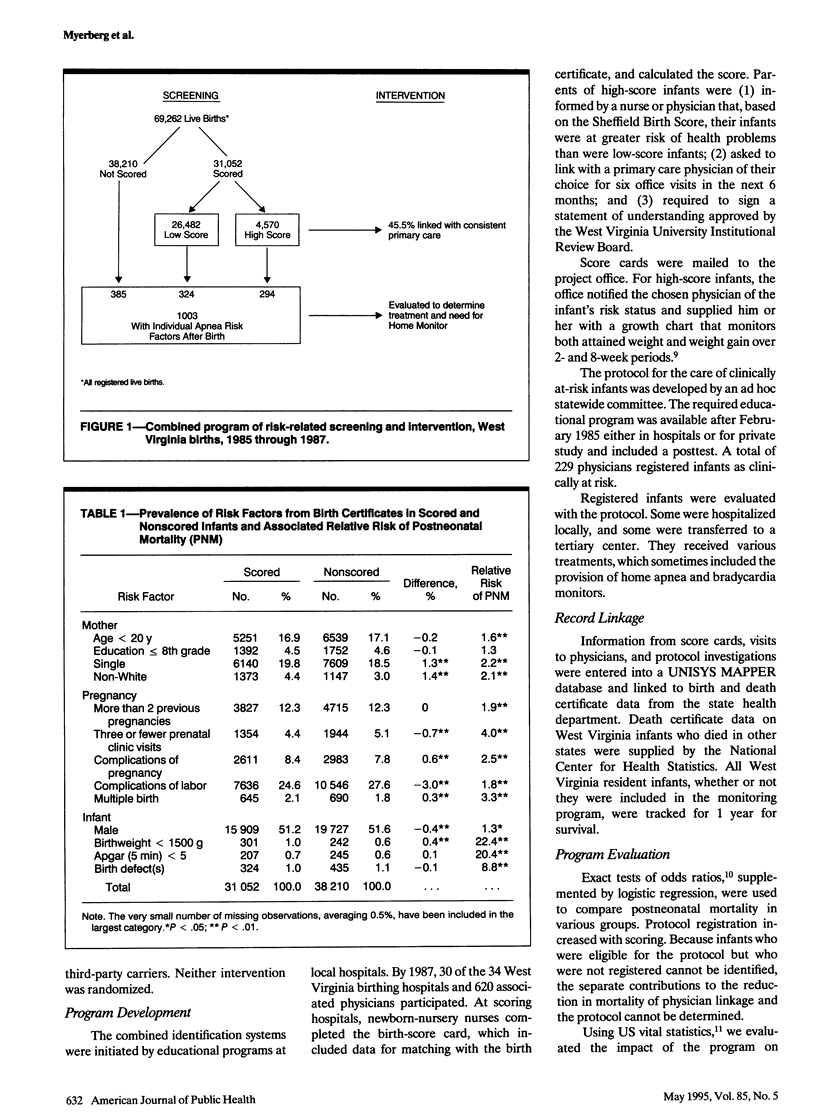

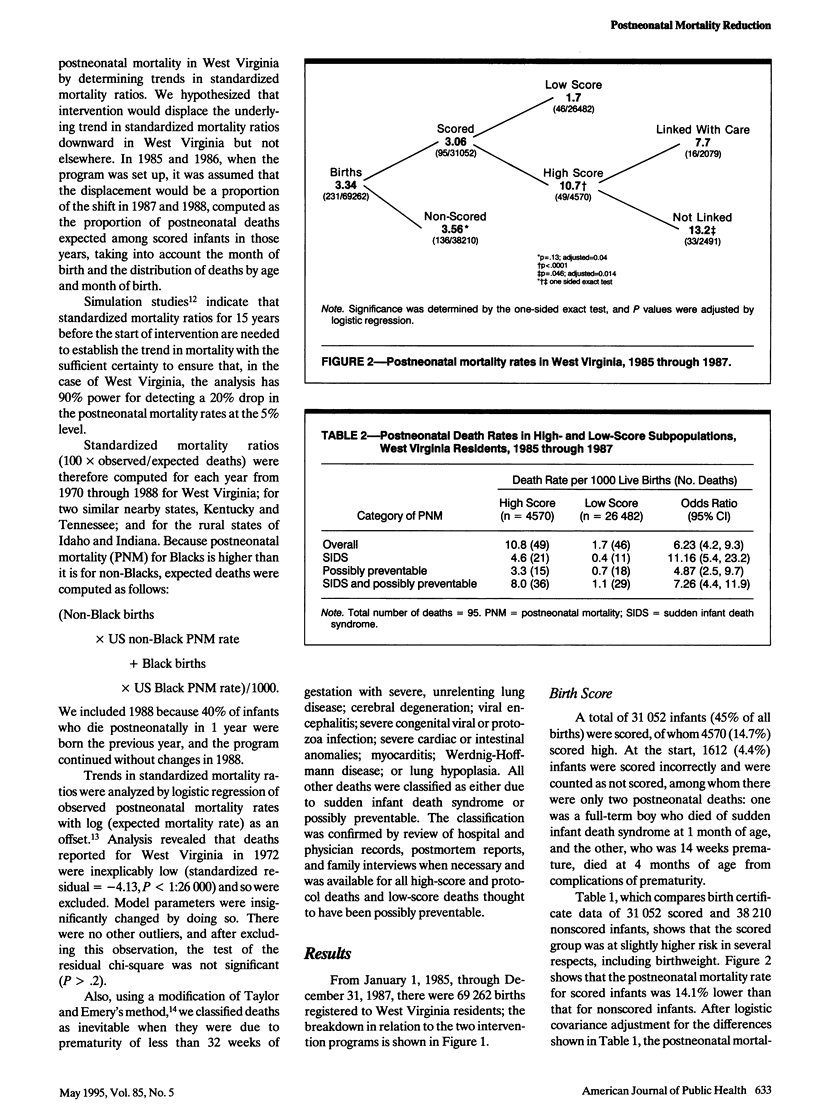

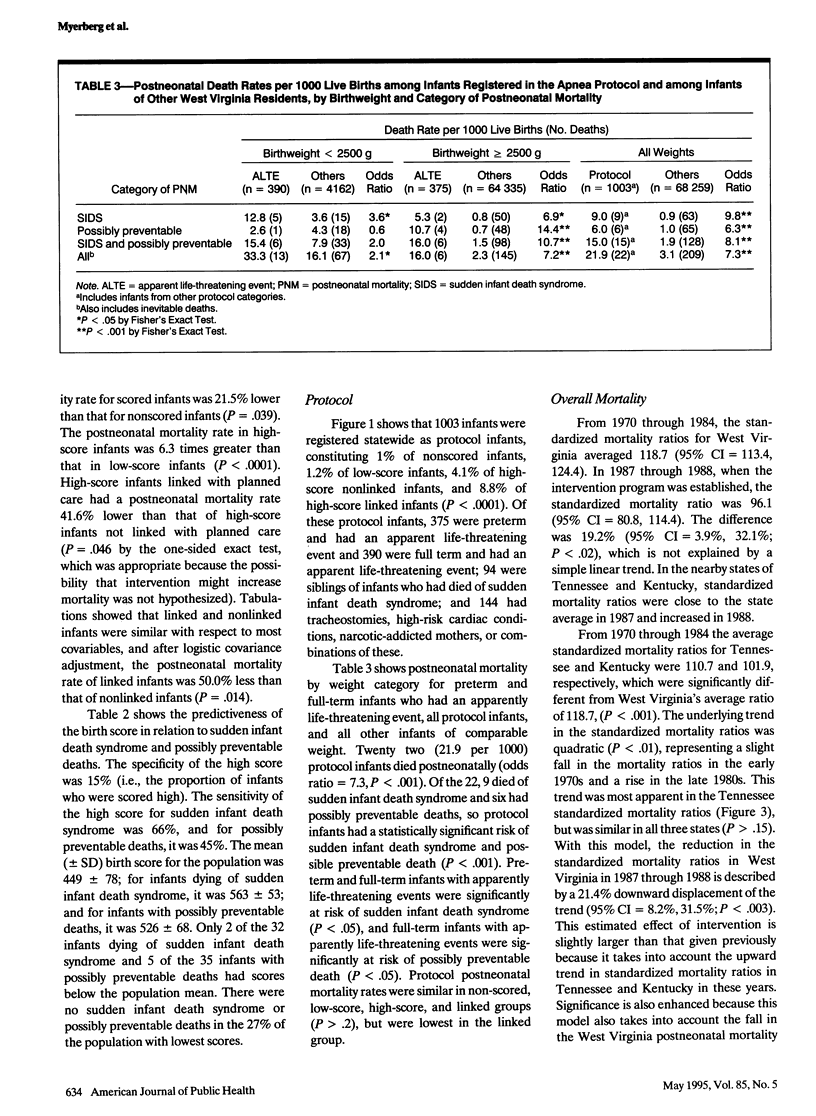

OBJECTIVES. Excessive postneonatal mortality in West Virginia has been associated with inadequate health care. This paper describes two interventions aimed at those infants at greatest risk of dying. METHODS. Two systems of risk-related intervention were simultaneously introduced and funded statewide from 1985 through 1987. Risk status was determined by a multifactorial score at birth or clinical risk factors later. At-risk infants were linked with physicians who provided specified care plans. All infants were followed for 1 year for mortality. RESULTS. Of 4570 infants with a high Sheffield Birth Score, 45%, together with 1003 infants with clinical risk factors, received specified care plans. High-risk infants constituted 7.6% of total resident births. Odds ratios for overall postneonatal mortality and sudden infant death syndrome in high-birth-score infants compared with low-birth-score infants were 6.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.2, 9.3) and 11.2 (95% CI = 5.4, 23.2), respectively. The relative risks of postneonatal mortality were similarly significant for infants with most clinical risk factors. During the program there was a 21.4% reduction in the trend of yearly standardized mortality ratios, which differed markedly from the trend in surrounding states. The data suggest that 33 lives were saved at a cost of $36,363 per infant. CONCLUSION. Ensuring affordable, available, accessible, and acceptable care for a small group of at-risk infants was associated with a dramatic drop in overall postneonatal mortality in West Virginia.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bazzoli G. J. Health care for the indigent: overview of critical issues. Health Serv Res. 1986 Aug;21(3):353–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter R. G., Emery J. L. Final results of study of infants at risk of sudden death. Nature. 1977 Aug 25;268(5622):724–725. doi: 10.1038/268724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter R. G., Gardner A., Harris J., Judd M., Lewry J., Maddock C. R., Powell J., Taylor E. M. Prevention of unexpected infant death. A review of risk-related intervention in six centers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;533:96–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb37237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter R. G., Gardner A., Jepson M., Taylor E. M., Salvin A., Sunderland R., Emery J. L., Pursall E., Roe J. Prevention of unexpected infant death. Evaluation of the first seven years of the Sheffield Intervention Programme. Lancet. 1983 Apr 2;1(8327):723–727. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druschel C. M., Hale C. B. Postneonatal mortality among normal birth weight infants in Alabama, 1980 to 1983. Pediatrics. 1987 Dec;80(6):869–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery J. L., Waite A. J., Carpenter R. G., Limerick S. R., Blake D. Apnoea monitors compared with weighing scales for siblings after cot death. Arch Dis Child. 1985 Nov;60(11):1055–1060. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.11.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigfeld L. S., Kaplan D. W. Native American postneonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 1987 Oct;80(4):575–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason J. M., Jarvis W. R. Infectious diseases: preventable causes of infant mortality. Pediatrics. 1987 Sep;80(3):335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limerick S. R. Sudden infant death in historical perspective. J Clin Pathol. 1992 Nov;45(11 Suppl):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeley R. J., Hull D., Holland T. Prevention of postneonatal mortality. Arch Dis Child. 1986 May;61(5):459–463. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren J., Kelly D., Shannon D. C. Identification of a high-risk group for sudden infant death syndrome among infants who were resuscitated for sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 1986 Apr;77(4):495–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D. L., Stein J., Porta M., Porter C. Q., Ricketts T. C. Poverty, health services, and health status in rural America. Milbank Q. 1988;66(1):105–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protestos C. D., Carpenter R. G., McWeeny P. M., Emery J. L. Obstetric and perinatal histories of children who died unexpectedly (cot death). Arch Dis Child. 1973 Nov;48(11):835–841. doi: 10.1136/adc.48.11.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southall D. P., Samuels M. P. Strategies for the prevention of sudden unexplained infant death based on the hypothesis that intrapulmonary shunting with prolonged expiratory apnea is a major contributory mechanism. J Perinatol. 1989 Jun;9(2):191–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E. M., Emery J. L. Two-year study of the causes of postperinatal deaths classified in terms of preventability. Arch Dis Child. 1982 Sep;57(9):668–673. doi: 10.1136/adc.57.9.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudehope D. I., Cleghorn G. Home monitoring for infants at risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. Aust Paediatr J. 1984 May;20(2):137–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1984.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]