Abstract

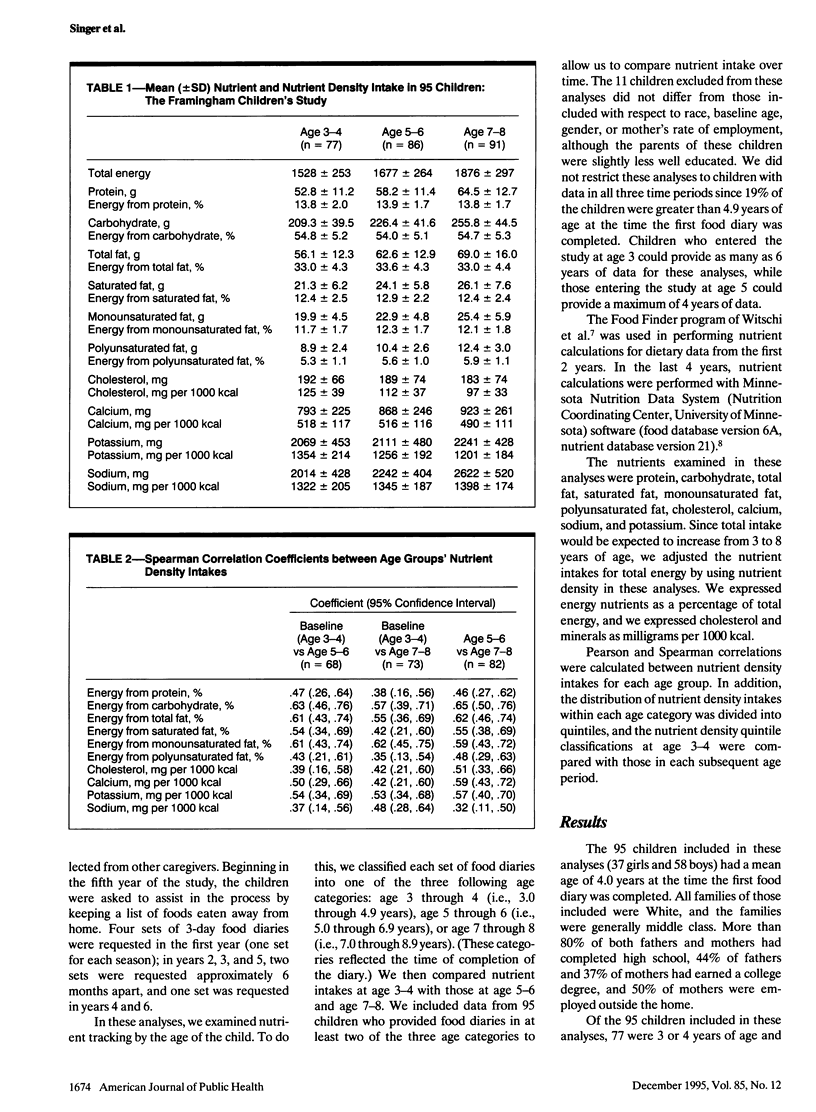

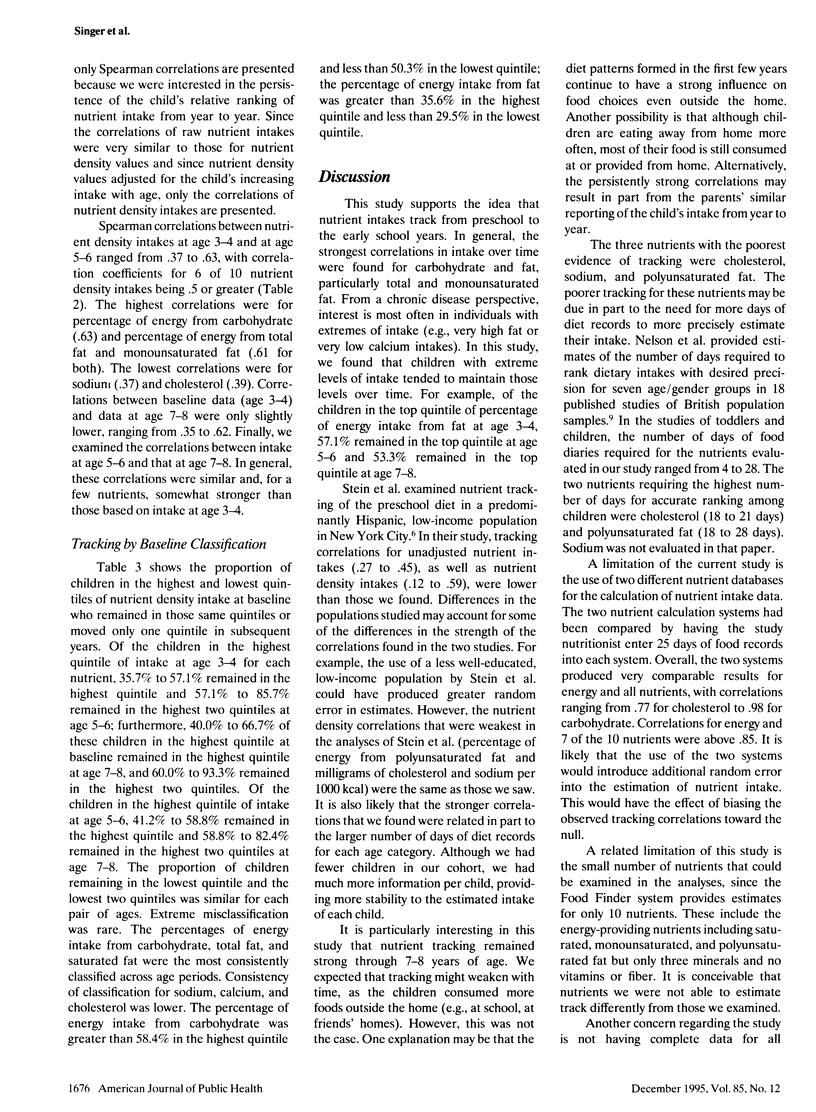

OBJECTIVES. This study compared the nutrient intake of children at 3 through 4 years of age with that in subsequent years to determine whether nutrient intake tracked over time. METHODS. Intakes of 10 nutrients were estimated by means of multiple days of food diaries collected over a span of up to 6 years of follow-up for 95 children in the Framingham Children's Study. All diaries collected during each of three age periods (age 3 through 4, age 5 through 6, and age 7 through 8) were averaged. Nutrient density intakes at each age period were compared. RESULTS. Nutrient-specific correlations ranged from .37 to .63 between nutrient density intakes at age 3-4 and age 5-6. Correlations between intakes at age 3-4 and age 7-8 ranged from .35 to .62. Consistency of classification was strong; 35.7% to 57.1% of children in the highest quintile of intake at age 3-4 remained in that quintile at age 5-6, and 57.1% to 85.7% remained in the top two quintiles. At age 7-8, 40.0% to 66.7% of those with the highest intake at baseline were still in the top quintile, and 60.0% to 93.3% remained in the top two quintiles. Results were similar in the lowest quintile of intake. Extreme misclassification was rare. CONCLUSIONS. This study suggests that tracking of nutrient intake begins as young as 3-4 years of age.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Berenson G. S., Srinivasan S. R., Hunter S. M., Nicklas T. A., Freedman D. S., Shear C. L., Webber L. S. Risk factors in early life as predictors of adult heart disease: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Med Sci. 1989 Sep;298(3):141–151. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder S. H., Perry C. L., Klepp K. I., Lytle L. L. Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1994 Jul;84(7):1121–1126. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer R. M., Lee J., Clarke W. R. Factors affecting the relationship between childhood and adult cholesterol levels: the Muscatine Study. Pediatrics. 1988 Sep;82(3):309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M., Black A. E., Morris J. A., Cole T. J. Between- and within-subject variation in nutrient intake from infancy to old age: estimating the number of days required to rank dietary intakes with desired precision. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989 Jul;50(1):155–167. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schakel S. F., Sievert Y. A., Buzzard I. M. Sources of data for developing and maintaining a nutrient database. J Am Diet Assoc. 1988 Oct;88(10):1268–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S., Basch C. E., Irigoyen M., Zybert P., Rips J. L., Contento I., Gutin B. Relationships of dietary fat consumption to serum total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in hispanic preschool children. Prev Med. 1991 Mar;20(2):237–249. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90023-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A. D., Shea S., Basch C. E., Contento I. R., Zybert P. Variability and tracking of nutrient intakes of preschool children based on multiple administrations of the 24-hour dietary recall. Am J Epidemiol. 1991 Dec 15;134(12):1427–1437. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witschi J., Kowaloff H., Bloom S., Slack W. Analysis of dietary data; an interactive computer method for storage and retrieval. J Am Diet Assoc. 1981 Jun;78(6):609–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]