Abstract

Well ordered reproducible crystals of cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides yield a previously unreported structure at 2.0 Å resolution that contains the two catalytic subunits and a number of alkyl chains of lipids and detergents. Comparison with crystal structures of other bacterial and mammalian CcOs reveals that the positions occupied by native membrane lipids and detergent substitutes are highly conserved, along with amino acid residues in their vicinity, suggesting a more prevalent and specific role of lipid in membrane protein structure than often envisioned. Well defined detergent head groups (maltose) are found associated with aromatic residues in a manner similar to phospholipid head groups, likely contributing to the success of alkyl glycoside detergents in supporting membrane protein activity and crystallizability. Other significant features of this structure include the following: finding of a previously unreported crystal contact mediated by cadmium and an engineered histidine tag; documentation of the unique His–Tyr covalent linkage close to the active site; remarkable conservation of a chain of waters in one proton pathway (D-path); and discovery of an inhibitory cadmium-binding site at the entrance to another proton path (K-path). These observations provide important insight into CcO structure and mechanism, as well as the significance of bound lipid in membrane proteins.

Keywords: cadmium binding, membrane protein structure, proton-conducting water chains

Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is the terminal enzyme in the electron transfer chain in eukaryotes and many bacteria. It provides the final electron sink by accepting electrons from cytochrome c and reducing oxygen to water (1). The energy generated from this reaction is used to translocate protons across the membrane against the membrane potential and pH gradient (2). The proton gradient so formed is then used to make ATP, a universal energy source. CcO is an intrinsic membrane protein with varying numbers of subunits from 3 in some bacteria to 13 in mammalian mitochondria. However, only subunits I and II, which contain the redox active heme and metal centers and are highly conserved among different species, are required for electron transfer and proton pumping activities. Other subunits, particularly the highly conserved subunit III, likely play key roles in stabilizing and regulating the enzyme activity and energy metabolism in general.

Over the past decade, several x-ray crystal structures of aa3-type CcOs from bovine heart mitochondria and bacteria have been determined (3–8). However, the mechanism of vectorial translocation of protons by CcO remains to be solved (9). It is now recognized that water molecules play a critical role in facilitating and controlling proton transfer (10). Thus, high-resolution crystal structures of different redox states and key mutants with defined waters are necessary to elucidate the energy conservation process. However, achieving a reproducible high-resolution structure of membrane proteins remains a major challenge.

As a result of our efforts to accomplish this goal, we report a crystal structure of the two-subunit catalytic core of Rhodobacter sphaeroides CcO (I-II RsCcO) at 2.0 Å resolution, produced from an engineered form of the enzyme and in the presence of cadmium. Unlike the crystals of the four-subunit RsCcO (8), the two-subunit crystal form can be grown reproducibly and diffracts x-rays isotropically. A number of alkyl chains of lipids and detergents are resolved in the structure, as seen in the high-resolution bovine CcO (7) and in other well resolved membrane protein structures (11). But, remarkably, when the I-II RsCcO structure is overlaid with previous structures of CcO from both closely [Paracoccus denitrificans (Pd)] and distantly (bovine) related species, almost all of the alkyl chain positions are found to be highly conserved, revealing specific lipid-binding sites. This finding provides perspective on the importance of lipid in membrane protein structure, function, and crystallization.

Results and Discussion

Engineering of a Molecularly Homogeneous CcO.

Efforts to successfully crystallize RsCcO are complicated by the inherent heterogeneity of the lipid membrane as well as the molecular heterogeneity of the protein itself. The latter is caused by the fact that (i) the enzyme undergoes incomplete processing of the C-terminal region of subunit II and (ii) there are alternative forms of subunit IV because of two translation start codons in the native gene (12). The native oxidase forms with differently processed subunits are not readily separated during purification and coexist in the crystals of the four-subunit RsCcO, negatively affecting the quality of x-ray diffraction. To maximize the homogeneity of the protein preparation, we took two approaches. First, a 6-histidine tag was attached to the C terminus of an artificially truncated subunit II (13) (Fig. 1), providing a uniform subunit II peptide. Second, the native gene for subunit IV was deleted from the bacterial genome. In the overexpression plasmid, either no subunit IV or a shortened version was introduced, eliminating the mixture of long and short forms of subunit IV that is present in the wild-type protein. These modifications proved to be important because the I-II subunit crystals did not form when there were significant amounts of the longer subunit IV in the enzyme complex.

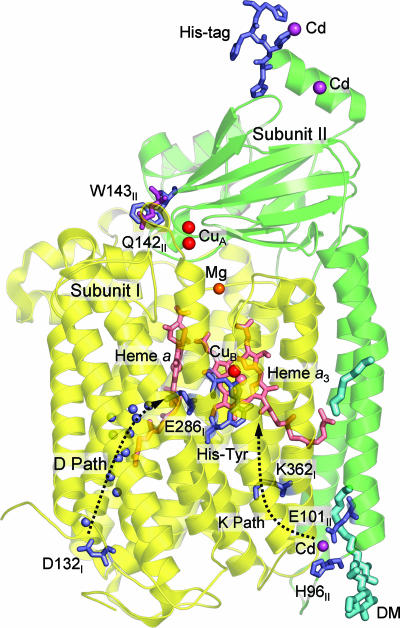

Fig. 1.

Important structural features of the two-subunit RsCcO. Subunit I is shown in yellow, and subunit II is shown in green. Residues of interest are shown in stick models and colored blue, except for Q142II, which is colored magenta for clarity. Heme groups are shown in salmon. Metals are shown as spheres and colored as follows: Fe, salmon; Cu, red; Mg, blue; Cd, magenta. Two proton uptake pathways are indicated by dotted arrows, with resolved waters in the D path shown as blue spheres. One of the resolved detergent molecules (DM-decyl maltoside), corresponding to the DM at the phosphatidyl choline (PC) site in Fig. 3C, is shown in cyan, as is one of the alkyl chains corresponding to the cardiolipin (CDL) site in Fig. 3B.

Minimizing Loss of Lipid During Purification.

A purification procedure was designed to reduce detergent exposure and the number of steps of chromatography to retain native lipid. [Adding back lipids (14) was not found to improve resolution in this case.] Controlling the exact protein/detergent ratio during purification was critical in crystal formation. A previous standard purification of RsCcO involved two nickel affinity columns and one ion exchange (8). Our revised protocol involves only one column chromatography by nickel affinity with a modified two-step gradient (see Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The purity was not quite as high as in the routine purification, but the visible spectral characteristics were the same (Fig. 8 Top, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Formation of a Two-Subunit Crystal with Isotropic Diffraction and a Cadmium/His-Tag Crystal Contact.

In a previous study (6), the I-II subunit crystal of CcO from P. denitrificans (PdCcO) was purposely obtained by using the strong detergent lauryldimethylamine-oxide (LDAO) to remove subunits III and IV (6). In the case of RsCcO, crystals of the I-II subunit complex emerged spontaneously and reproducibly, from the purified, engineered enzyme with either three or four subunits, in the presence of cadmium ion (see Methods and Supporting Methods). Fig. 1 shows the overall structure of the form.

Loss of subunit III/IV during the crystallization procedure may arise from the presence of cadmium, added in an effort to locate the site of inhibition of CcO by Zn2+ and Cd2+. In the four-subunit crystal form of RsCcO, we have found two cadmium-binding sites in subunit III (unpublished data), which may increase its already strong propensity to dissociate (15, 16). The short version of subunit IV is also likely to be more labile because of reduced protein:protein contact.

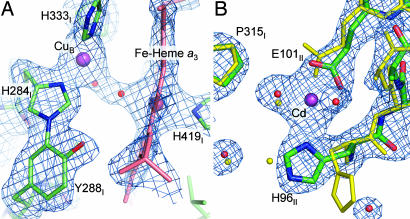

Compared with the four-subunit RsCcO crystals, which quickly dissolved upon raising the temperature above 4°C, the I-II RsCcO crystals are stable and can be reproducibly grown at room temperature, although those grown at 4°C diffract better. Furthermore, the crystals of four-subunit RsCcO displayed considerable anisotropic x-ray diffraction, which resulted in limiting the resolution to 2.3 Å along a* and b*, but only to 2.8 Å along c* (8). In contrast, the crystals of the I-II subunit form display no significant diffraction anisotropy to 2.0 Å resolution. An analysis of the crystal contacts reveals a major contact region involving the extramembrane domain of subunit II that is mediated by two cadmium ions and two histidine tags (Fig. 2). Each cadmium ion is liganded in a tetrahedral coordination geometry by three amino acid side chains from one RsCcO molecule, including a glutamate and two histidines from the histidine tag and a glutamate residue from another RsCcO molecule. An identical contact exists close by, involving the histidine tag and the same residues from the neighboring RsCcO molecule in the asymmetric unit. This strong contact may be responsible for the superior x-ray diffraction properties and stability of the I-II subunit crystals.

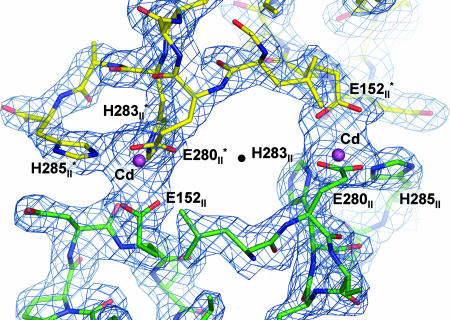

Fig. 2.

Major crystal contact region of I-II RsCcO contributed by two engineered histidine tags at the C terminus of subunit II and two cadmium ions. One RsCcO molecule is colored by atom type (C, green; O, red; N, blue); the other molecule is colored similarly but C is yellow. Cadmium is purple. The (2Fo − Fc) electron density map contoured at 1.3σ is shown in blue. The participating amino acid residues from the two protein molecules form a tetrahedral coordination around the cadmium ion as labeled in the figure. There are two identical crystal contact interactions at this interface with a quasi-2-fold rotational symmetry axis (shown as a black dot) at the center perpendicular to the plane of the paper.

Structural and Biochemical Characteristics of the I-II RsCcO Crystals.

As in the case of the two-subunit PdCcO obtained under very different conditions (6), the I-II RsCcO is structurally similar to the core of the four-subunit enzyme. The redox active metal centers found in the four-subunit structures are all present in the I-II subunit structure (Fig. 1), with identical ligations. Unlike the four-subunit crystal structure, there are two independent I-II RsCcO molecules in the asymmetric unit, and the structures are slightly different in terms of resolution of water and other bound molecules.

The redissolved I-II RsCcO crystals are highly active and display native spectral characteristics (Fig. 8). The enzymatic activity decreases as the enzyme turns over in steady-state measurements, a phenomenon typical of CcO missing subunit III (17) (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Adding lipid and arachidonic acid protects the enzyme from undergoing this “suicide” inactivation (18) (Fig. 9). The initial activity is similar to that reported for purified subunit III-minus enzyme, even though these crystals had been maintained under crystallization conditions for ≈3 months before being dissolved and assayed. The high activity observed supports previous conclusions that the subunit III-minus oxidase is very stable unless it is undergoing turnover (18).

Conserved Sites of Detergent and Lipid Interaction.

Beyond providing a hydrophobic solvent and diffusion barrier, many studies suggest that membrane lipids can contribute to functional aspects of associated proteins (19, 20). Only recently has it been possible to obtain high enough resolution crystal structures of membrane proteins to identify bound lipids. The significance of the associated lipids is only beginning to be recognized (19, 20).

In the crystal structure of the four-subunit RsCcO, a total of six phosphatidyl ethanolamines were identified, four surrounding subunit IV and two associated with subunits III and I (8). Subunit IV interacts with its neighboring subunits almost entirely via lipid molecules (8), emphasizing the integral nature of the lipid. In the I-II RsCcO structure, all these lipids are lost, not surprisingly because they are most strongly associated with the missing subunits. However, in other locations, there are well resolved detergent molecules, as well as a number of tube-like electron densities interpreted as hydrocarbon tails of either native membrane lipids or detergent molecules, because they are found in the transmembrane region of the enzyme (Figs. 3A and 4). The headgroups of these hydrocarbon tails are not resolved, suggesting that they are flexible, possibly because of the high salt concentration in the crystallization medium. This phenomenon of unresolved head groups was observed in the case of lipids identified in bacteriorhodopsin, even at 1.55 Å resolution (11).

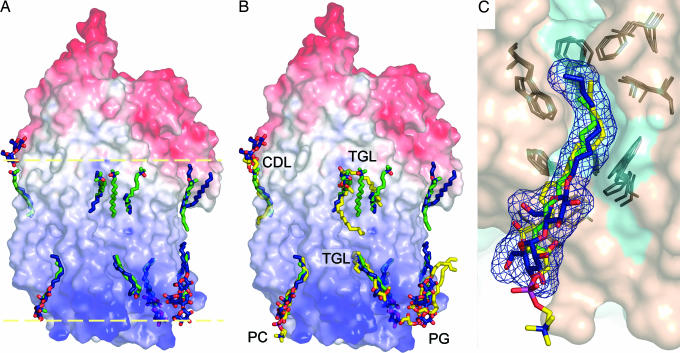

Fig. 3.

Surface representations of I-II RsCcO illustrating the position and superposition of detergent/lipid molecules in Rs, Pd, and bovine CcO structures. The superpositions were identified by overlaying the structures of I-II RsCcO, I-II PdCcO (PDB ID code 1AR1), and bovine heart mitochondrial CcO (PDB ID code 1V54). (A) Molecular surface representations of I-II RsCcO, colored by relative electrostatic potential (blue, positive; red, negative) and showing the detergent molecules, maltose headgroups, and alkyl chains resolved in the structure (C, dark blue; O, red), superimposed on the LDAO detergent molecules resolved in the I-II PdCcO structure (C, green; O, red; N, blue). The lipid bilayer region is represented by two yellow dashed lines. (B) Lipid molecules in the bovine CcO structure that occupy the same sites as alkyl chains resolved in Rs/Pd structures are shown (C, yellow). Structures of RsCcO and PdCcO are colored as in A. PC, phosphatidyl choline; PG, phosphatidyl glycerol; CDL, cardiolipin; TGL, triacylglycerol. (C) Detailed view of one of the conserved lipid-binding sites, where an alkyl chain of phosphatidyl choline resolved in bovine CcO occupies the same site as detergents resolved in RsCcO and PdCcO. Surface representation of I-II RsCcO is colored by subunits (subunit I, cyan; subunit II, wheat). The decyl maltoside from RsCcO, the detergent LDAO from PdCcO, and the partial lipid molecule in bovine CcO are colored by atom type as above. The mesh representation of the resolved decyl maltoside is shown in blue. Some well conserved residues in all three structures surrounding the alkyl chain-binding site are colored dark gray.

Fig. 4.

Characteristics of detergent molecules resolved in the I-II RsCcO structure. (A) Two decyl maltoside detergent molecules (colored by atom type: C, green; O, red; N, blue) resolved at the interface of two RsCcO molecules (gray and wheat). The (2Fo − Fc) difference electron density map (dark blue) surrounding the decyl maltosides contoured at 1.3 σ is shown. Tyrosine and tryptophan residues (blue) were found stacking with the head groups of the two decyl maltosides. (B) One decyl maltoside resolved on another location, also at molecular interface. The (2Fo − Fc) difference electron density map (dark blue) contoured at 1.0σ is shown. Phenylalanine residue (blue) was found forming a stacking interaction with the sugar ring.

An interesting observation was made when the crystal structures of the I-II CcO enzymes from Rs and Pd (6) were overlaid (Fig. 3A). In both cases, alkyl chains are resolved in the region where membrane lipids would normally interact. Surprisingly, many of the chains occupy essentially identical positions on the surface of the two proteins, despite the fact that the structures are from different species and underwent different purification and crystallization procedures by using different detergents. The implication is that these locations are conserved sites for specific interactions of membrane lipids with the transmembrane protein surface.

Indeed, superposition of the I-II RsCcO structure on the 1.8-Å resolution bovine heart CcO structure, in which 13 lipids are resolved (7), reveals that most of the alkyl chains in I-II RsCcO coincide not only with those in the PdCcO but also with chains of lipid molecules in bovine CcO, as shown in Fig. 3B. A closer view in Fig. 3C shows the crevice occupied by a decyl maltoside in RsCcO, an LDAO detergent in PdCcO, and one of the alkyl tails of a phosphatidyl choline in bovine CcO. Also illustrated are residues that seem to be involved in creating the lipid crevice, which are well conserved in all three CcO structures. Similar conservation can be found for residues in the vicinity of two other decyl maltosides occupying roughly the same sites as the alkyl tails of a phosphatidyl glycerol molecule resolved in bovine CcO (Fig. 10A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

In other locations, resolved alkyl tails in I-II RsCcO and PdCcO also correspond to lipids in bovine CcO, such as a cardiolipin molecule in the bovine CcO structure (Figs. 3B and 10B). Cardiolipin has been implicated in the function of electron transfer complexes in the respiratory chain (19, 20), and our mass spectrometric analyses consistently show the preferential retention of cardiolipin in the purified RsCcO enzyme and in redissolved crystals (X. Zhang, L.Q., and S.F.-M., unpublished data). Therefore, the alkyl tail resolved here could indeed be from the bound cardiolipin molecule at this conserved site. The highly ionic cardiolipin head group and flexible, unsaturated alkyl tails may account for incomplete resolution under the crystallization conditions.

Where decyl maltoside detergents are resolved (Fig. 4), nearby aromatic residues form stacking interactions between the sugar rings and the aromatic rings. The same intimate interaction can be observed in a number of other membrane protein structures (21, 22). Alkyl glycoside headgroups seem to mimic phosphatidyl head groups in their well known interactions with tryptophan and tyrosine (19, 23). Their ability to effectively occupy specific lipid-binding sites may account for their success in stabilizing and crystallizing membrane proteins. These observations suggest that detergent molecules resolved in a membrane protein structure likely reveal where a phospholipid should be bound. In support of this idea is the observation that surface regions in I-II RsCcO that were originally covered by subunits III and IV show no lipid/detergent-binding sites (data not shown).

The above findings strongly support a conclusion that there are specific, conserved interaction sites for lipids on membrane proteins and that a detergent with the right properties can at least partially occupy the same site.

Conserved Waters in Proton Pathways.

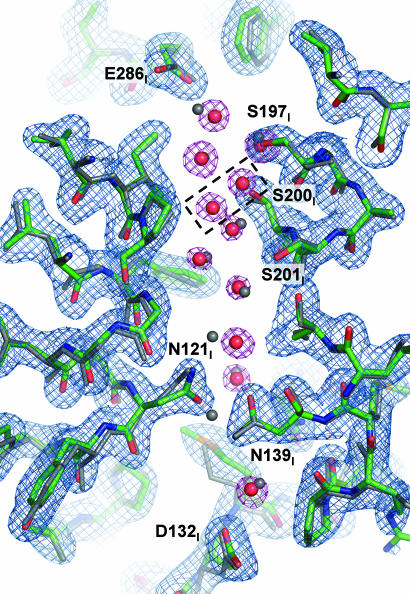

There are two established proton pathways in the enzyme: D and K pathways, named after the residues D132I and K362I, whose mutational replacement blocks each path (24–26) (Fig. 1). In the four-subunit RsCcO crystal structure (8), a clear chain of waters was resolved in the D pathway from D132I leading to the vicinity of E286I, a residue thought to be critical in conducting protons to the active site and to the external bulk phase (27).

In the current structure, the chain of waters is again clearly resolved. Fig. 5 shows the comparison of the resolved D channel waters in the I-II subunit and four-subunit RsCcO structures. The positions of the waters and the conformations of the amino acid residues along the pathway are very similar between the two structures except for N121I, which is reoriented. This observation is consistent with the lack of one water in the I-II RsCcO structure, which is liganded to the N121I side chain in the four-subunit structure. There are two additional waters resolved in the I-II subunit structure further up in the pathway close to S200I (Fig. 5, box). The high degree of conservation of these ordered, hydrogen-bonded waters is consistent with their importance in determining rate and directionality of proton movement. The slight difference between the four-subunit and I-II subunit structure in the water arrangement in the D pathway could be related to the absence of subunit III. Although not essential for either electron transfer or proton pumping, subunit III is in close proximity to the D pathway and seems to play a role in the kinetics of proton uptake by this channel (28). The K pathway has few waters resolved in the four-subunit structure (8), but again their positions are conserved in the I-II subunit RsCcO structure. Overall, there is remarkable conservation of water positions in the CcO structures, suggesting a critical role of water in proton transfer (10).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the resolved waters in the D proton uptake pathway in the crystal structures of I-II RsCcO and the four-subunit RsCcO. The I-II RsCcO structure is colored by atom type (C, green; O, red; N, blue), and the structure of the four-subunit RsCcO (PDB ID code 1M56) is colored gray. Waters in I-II RsCcO structure are red; waters in four-subunit RsCcO are gray. The dotted black box indicates two additional waters resolved in the I-II RsCcO. The (2Fo − Fc) difference electron density map contoured at 1.0σ is shown in blue and magenta.

Structure of the Active Site: Bridging Ligand and His–Tyr Covalent Linkage.

Heme a3 and CuB form the active site of the enzyme where oxygen is reduced to water. A unique covalent linkage between the Cε2 of Y288I and the Nε2 of a CuB ligand, H284I, is observed in the crystal structures of CcO from bovine heart and Pd (4, 6), and its presence is supported by mass spectrometry analysis (29). The linkage was not resolved unequivocally in the crystal structure of the four-subunit RsCcO. A mixture of covalently linked and noncovalently linked species could account for the observed density, calling into question the functional significance of the cross-link (8). In the current structure, well resolved electron density that is best fit by the cross-linked form is observed between the Nε2 of H284I and Cε2 of Y288I in a simulated annealing omit map contoured at 4.0 σ (Fig. 6A). This finding supports the concept that the covalently linked His-Tyr is important in the catalytic mechanism; the adduct is proposed to lower the pKa of the tyrosine OH group and facilitate free radical formation of Y288I (4, 30).

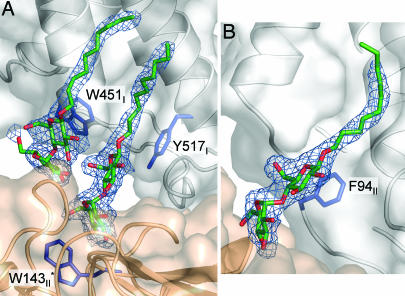

Fig. 6.

Detailed structure of the metal ligands at the active site (A) and the inhibitory cadmium-binding site (B). (A) The covalent linkage between ring atoms of Y288I and H284I. The (Fo − Fc) difference simulated annealing omit map is shown in blue, contoured at 4.0 σ, calculated by omitting CuB, H284I, Y288I, Fe of Heme a3, and all residues including heme a3 that have atoms closer than 3 Å to them. The amino acid residues are colored by atom type (C, green; O, red; N, blue), the heme group is colored light red, and the CuB atom is colored purple. The ligands tentatively assigned as a water bound to heme a3-Fe and an OH− group bound to CuB are both colored in red. (B) An inhibitory cadmium-binding site in the structure of I-II RsCcO. The (2Fo − Fc) difference electron density map contoured at 1.3σ is shown. In the current structure (colored by atom type: C, green; O, red; N, blue), cadmium (purple) is bound to E101II and H96II of subunit II. Binding of cadmium alters the conformations of the ligating residues compared with that found in the unliganded four-subunit RsCcO crystal structure (yellow).

Between the Fe in the heme a3 and the CuB center, there is residual density in the (Fo − Fc) map. Previously, observed density in this region has been interpreted as a water molecule ligated to Fea3 and a hydroxide ion to CuB (6) or a peroxy-bridge in the binuclear center (4). It is difficult to unambiguously assign the position and identity of the ligands in this pocket because of the presence of heavy atoms of Fe and Cu, as well as the uncertainty regarding the redox state during x-ray analysis. Although the peroxy-bridge seems to fit the electron density fairly well, the presence of such a peroxy form is not expected in the oxidized enzyme. We tentatively interpret this electron density as a hydroxide bound to CuB and a less well resolved water molecule bound to heme a3-Fe (Fig. 6A).

Inhibitory Cadmium-Binding Site.

It was previously observed that Zn2+ or Cd2+ inhibits CcO activity both in the purified state and in reconstituted lipid vesicles under steady-state turnover (31). Besides the cadmium-binding sites found at the crystallographic interface, an additional cadmium-binding site was identified in both RsCcO molecules, involving side chain atoms of E101II and H96II, as shown in Figs. 1 and 6B. This cadmium-binding site was confirmed by anomalous difference Fourier map and was also observed in the structure of the four-subunit RsCcO when the crystal was soaked in a CdCl2 solution before flashcooling (unpublished data). E101II has been suggested to be the proton entry point for the K pathway in RsCcO (32). The observed cadmium-binding site could account for the inhibition of activity of the purified enzyme, by blockage of the K pathway for proton uptake. It is likely, however, that the observed Zn2+/Cd2+ inhibitory effect on the enzyme involves more than one site (33). The lack of binding of Zn2+/Cd2+ at the opening of the D path in this crystal structure could be due to the loss of subunit III, which provides several histidines close to the D channel entrance.

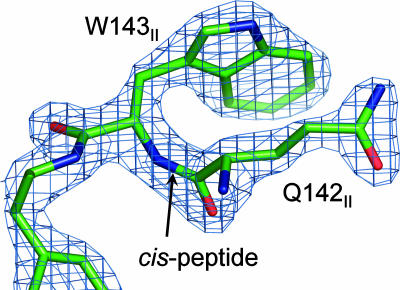

Cis-Peptide Bond Between Q142II and W143II at the Electron Transfer Interface.

Electrons enter CcO from cytochrome c at the CuA center, apparently via the indole ring of a tryptophan residue, W143II (34–36). W143II and Q142II are highly conserved and at the center of the predicted interface between cytochrome c and CcO (37). Interestingly, the peptide bond between Q142II and W143II is a cis-peptide bond (Fig. 7). This cis-peptide bond has not been previously noted in CcO; it is often missed because of its rare occurrence (38). The presence of such a bond is important in orienting the side chains of flanking residues in the same direction, in this case toward the proposed cytochrome c-binding site, and permitting close association between the indole ring and the glutamine through dipole–quadrupole interaction (38). A role in facilitating the electron conducting interface may be surmised.

Fig. 7.

The cis-peptide bond found between Q142II and W143II. The structure is colored by atom type (C, green; O, red; N, blue). The (2Fo − Fc) difference electron density map contoured at 1.3σ is shown in blue.

Summary.

Reproducible, well ordered crystals of a two-subunit RsCcO provide important insight into its structure, function, and specific association with lipid and water. The observations of conserved water positions and conserved sites for lipid or detergent reveal a critical role for specifically bound “solvent” molecules in membrane protein structure and activity.

Methods

The detailed descriptions of molecular cloning, protein purification, crystallization, x-ray diffraction data collection, and structure determination are included in Supporting Methods. Dodecyl maltoside and Ni-NTA were used in purification, and decyl and dodecyl maltoside were used in crystallization. X-ray diffraction data were collected on a single frozen crystal at Beamline 5ID-B [Dupont–Northwestern–Dow (DND) Collaborative Access Team (CAT), Advanced Photon Source (APS)]. The structure was determined by molecular replacement by using the published four-subunit RsCcO structure (PDB ID code 1M56) as the starting search model. Structural refinement was performed by using CNS and Refmac5, with final Rwork and Rfree factors of 21.4% and 23.2%, respectively. The anomalous diffraction data were collected at Beamline 23ID-D [General Medicine and Cancer Institutes (GM/CA)-CAT, APS]. The x-ray data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kaillathe Padmanabhan, Rachel Powers, Christine Harman, and Nicole Webb for helpful discussions and suggestions regarding data collection and structural refinement; Xi Zhang, Dr. Yasmin Hilmi, Dr. Steve Seibold, and Sarah House for contributions; staff from GM/CA-CAT, DND-CAT, and Life Sciences (LS)-CAT at APS for assistance at the synchrotron facility; Dr. Zdzislaw Wawrzak from DND-CAT, APS for the initial processing of x-ray diffraction data; and Drs. Margareta Svensson-Ek, So Iwata, and Peter Brzezinski for support and collaboration. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant GM26916, Human Frontier Science Program Grant RG315/2000-M, Michigan Technology TriCorridor Center for Structural Biology, Core Technology Alliance Grant 085P1000817, NIH Grant P01GM57323, and Michigan State University Grant REF03-016.

Abbreviations

- Rs

R.sphaeroides

- Pd

P.denitrificans

- CcO

cytochrome c oxidase

- I-II RsCcO

the two-subunit version of RsCcO

- LDAO

lauryldimethylamine-oxide.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

Data deposition footnote: The complete coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2GSM).

References

- 1.Ferguson-Miller S, Babcock GT. Chem Rev (Washington, DC) 1996;96:2889–2907. doi: 10.1021/cr950051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wikstrom MK. Nature. 1977;266:271–273. doi: 10.1038/266271a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwata S, Ostermeier C, Ludwig B, Michel H. Nature. 1995;376:660–669. doi: 10.1038/376660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshikawa S, Shinzawa-itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yamashita E, Inoue N, Yao M, Fei MJ, Libeu CP, Mizushima T, et al. Science. 1998;280:1723–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. Science. 1996;272:1136–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostermeier C, Harrenga A, Ermler U, Michel H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10547–10553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsukihara T, Shimokata K, Katayama Y, Shimada H, Muramoto K, Aoyama H, Mochizuki M, Shinzawa-itoh K, Yamashita E, Yao M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15304–15309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2635097100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svensson-Ek M, Abramson J, Larsson G, Tornroth S, Brzezinski P, Iwata S. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills DA, Ferguson-Miller S. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharpe MA, Qin L, Ferguson-Miller S. In: Biophysical and Structural Aspects of Bioenergetics. Wikstrom M, editor. Cambridge, UK: R Soc Chem; 2005. pp. 26–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luecke H, Schobert B, Richter H-T, Cartailler J-P, Lanyi JK. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:899–911. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Distler AM, Allison J, Hiser C, Qin L, Hilmi Y, Ferguson-Miller S. Eur J Mass Spectrom. 2004;10:295–308. doi: 10.1255/ejms.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiser C, Mills DA, Schall M, Ferguson-Miller S. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1606–1615. doi: 10.1021/bi0018988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Kurisu G, Smith JL, Cramer WA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5160–5163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931431100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson DA, Ferguson-Miller S. Biochemistry. 1983;22:3178–3187. doi: 10.1021/bi00282a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bratton MR, Pressler MA, Hosler JP. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16236–16245. doi: 10.1021/bi9914107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosler JP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1655:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills DA, Hosler JP. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4656–4666. doi: 10.1021/bi0475774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palsdottir H, Hunte C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunte C. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:938–942. doi: 10.1042/BST20050938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snijder HJ, Van Eerde JH, Kingma RL, Kalk KH, Dekker N, Egmond MR, Dijkstra BW. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1962–1969. doi: 10.1110/ps.17701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada T, Fujiyoshi Y, Silow M, Navarro J, Landau EM, Shichida Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5982–5987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082666399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yau W-M, Wimley WC, Gawrisch K, White SH. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14713–14718. doi: 10.1021/bi980809c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Horsman JA, Puustinen A, Gennis RB, Wikstrom M. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4428–4433. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fetter JR, Qian J, Shapleigh J, Thomas JW, Garcia-Horsman A, Schmidt E, Hosler J, Babcock GT, Gennis RB, Ferguson-Miller S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1604–1608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas JW, Lemieux LJ, Alben JO, Gennis RB. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11173–11180. doi: 10.1021/bi00092a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofacker I, Schulten K. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1998;30:100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills DA, Tan Z, Ferguson-Miller S, Hosler J. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7410–7417. doi: 10.1021/bi0341307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buse G, Soulimane T, Dewor M, Meyer HE, Bluggel M. Protein Sci. 1999;8:985–990. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.5.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Proshlyakov DA, Pressler MA, DeMaso C, Leykam JF, DeWitt DL, Babcock GT. Science. 2000;290:1588–1591. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mills DA, Schmidt B, Hiser C, Westley E, Ferguson-Miller S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14894–14901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Branden M, Tomson F, Gennis RB, Brzezinski P. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10794–10798. doi: 10.1021/bi026093+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aagaard A, Namslauer A, Brzezinski P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1555:133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witt H, Malatesta F, Nicoletti F, Brunori M, Ludwig B. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5132–5136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhen Y, Hoganson CW, Babcock GT, Ferguson-Miller S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:38032–38041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang K, Zhen Y, Sadoski R, Grinnell S, Geren L, Ferguson-Miller S, Durham B, Millett F. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:38042–38050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts VA, Pique ME. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:38051–38060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jabs A, Weiss MS, Hilgenfeld R. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:291–304. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.