Abstract

We studied the effects of ranolazine, an antianginal agent with promise as an antiarrhythmic drug, on wild-type (WT) and long QT syndrome variant 3 (LQT-3) mutant Na+ channels expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells and knock-in mouse cardiomyocytes and used site-directed mutagenesis to probe the site of action of the drug.

We find preferential ranolazine block of sustained vs peak Na+ channel current for LQT-3 mutant (ΔKPQ and Y1795C) channels (IC50=15 vs 135 μM) with similar results obtained in HEK 293 cells and knock-in myocytes.

Ranolazine block of both peak and sustained Na+ channel current is significantly reduced by mutation (F1760A) of a single residue previously shown to contribute critically to the binding site for local anesthetic (LA) molecules in the Na+ channel.

Ranolazine significantly decreases action potential duration (APD) at 50 and 90% repolarization by 23±5 and 27±3%, respectively, in ΔKPQ mouse ventricular myocytes but has little effect on APD of WT myocytes.

Computational modeling of human cardiac myocyte electrical activity that incorporates our voltage-clamp data predicts marked ranolazine-induced APD shortening in cells expressing LQT-3 mutant channels.

Our results demonstrate for the first time the utility of ranolazine as a blocker of sustained Na+ channel activity induced by inherited mutations that cause human disease and further, that these effects are very likely due to interactions of ranolazine with the receptor site for LA molecules in the sodium channel.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, sodium channel, heart, persistent current, long QT syndrome

Introduction

Na+ channels (NaV1.5) primarily underlie action potential initiation and propagation in the heart, but more recently have been shown to be critical determinants of action potential duration (APD), particularly in the setting of certain arrhythmias (Moss & Kass, 2005; Kass, 2005). Inherited mutations in SCN5A, the gene coding for NaV1.5, are now known to underlie multiple inherited cardiac arrhythmias including the congenital long QT syndrome (LQT-3), Brugada syndrome, and isolated conduction disease (Clancy & Kass, 2005) and in most cases, these inherited mutations disrupt channel inactivation. Fast inactivation of Na+ channels is due to rapid block of the inner mouth of the channel pore by the cytoplasmic linker between domains III and IV, and it occurs within milliseconds of membrane depolarization (Catterall, 2000). The NaV1.5 carboxy-terminus (C-T) also has been shown to play a role in inactivation through chimeric studies (Mantegazza et al., 2001), the characterization of several disease-linked mutations found in the C-terminus (An et al., 1998; Bezzina et al., 1999; Veldkamp et al., 2000; Rivolta et al., 2001) and by direct biochemical evidence for C-T interactions with the cytoplasmic III–IV linker (Motoike et al., 2004). Inherited mutations of either the III/IV linker or the C-T domain in the cardiac Na+ channel can disrupt fast inactivation and promote persistent Na+ channel activity that can prolong APD and cause LQT-3 (Clancy & Kass, 2005).

Investigation into the clinical phenotype of patients harboring LQT-3 mutations as well as the biophysical and pharmacological properties of human Na+ channels with specific LQT-3 mutations has provided a critical bridge between molecular pharmacology and mutation-specific therapeutic approaches to the management of this disease (An et al., 1996; Shimizu & Antzelevitch, 1997; Dumaine & Kirsch, 1998; Abriel et al., 2000; Benhorin et al., 2000; Nagatomo et al., 2000; Viswanathan et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2002; 2003; Fabritz et al., 2003; Moss & Kass, 2005). This work has prompted reconsideration of possible contributions of persistent sodium channel activity to arrhythmogenesis in other cardiovascular disorders characterized by action potential (QT) prolongation such as heart failure (Valdivia et al., 2005) and has raised the possibility that pharmacological agents with preferential block of persistent (late) Na+ channel activity, while clearly important in the treatment of LQT-3 mutation carriers, may have more general utility in these other diseases as well. With this background in mind, we have investigated the modulation of wild-type (WT) and two LQT-3 mutant Nav1.5 Na+ channels by ranolazine and specifically tested for preferential inhibition of persistent channel activity as well as for the site of action of this drug.

Ranolazine is a novel antianginal drug (Pepine & Wolff, 1999; Louis et al., 2002; Chaitman et al., 2004), which prolongs modestly the corrected QT (QTc) interval in patients with chronic stable angina but is not known to increase the incidence of ventricular tachycardias and may reduce the incidence of ischemia-related arrhythmias (Gralinski et al., 1996). This drug is of particular interest because it has been recently shown to reduce sustained Na+ channel current, attenuate the prolongation of APD and suppress the development of arrhythmogenic early after depolarizations in a pharmacological model of LQT-3 in which sustained Na+ channel activity is induced by the toxin ATX-II (Song et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004). The antiarrhythmic potential of ranolazine has also been observed by Antzelevitch et al. (2004a) in isolated canine ventricular myocytes, which are known to have a large sustained Na+ current (Zygmunt et al., 2001) and in canine left ventricular wedge preparations pretreated with a IKr blocker (d-sotalol).

Here we report that ranolazine preferentially blocks persistent Na+ channel current carried by two LQT-3 mutant Nav1.5 channels: ΔKPQ (Wang et al., 1995) and Y1795C (Rivolta et al., 2001). These mutations were chosen because one (ΔKPQ) occurs within the cytoplasmic linker (inactivation gate) between domains III and IV and the other (Y1795C) occurs within the C-T of the sodium channel α subunit (Wang et al., 1995; Rivolta et al., 2001). Both mutations cause enhanced persistent Na+ channel activity (Bennett et al., 1995; Clancy et al., 2002). Currents were measured in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells expressing both ΔKPQ and Y1795C channels and in cardiomyocytes isolated from ΔKPQ knock-in mouse ventricular myocytes. Using site-directed mutagenesis of the previously defined local anesthetic (LA) receptor binding site in Nav1.5, we also provide evidence that the molecular basis of ranolazine modulation of WT and disease-associated mutant Nav1.5 channels is due to interactions with this site. Preferential block of mutation-induced persistent Na+ channel activity contributes to measured abbreviation of APD recorded in knock-in mouse myocytes and in the computed effects of ranolazine in a cellular model of human ventricular cells harboring ΔKPQ mutant Na+ channels. Our results suggest that ranolazine could be effective in treatment of LQT-3 arrhythmias via preferential block of persistent Na+ channel activity, and may have utility as an antiarrhythmic agent in other disorders characterized by Na+ channel-induced prolongation of APD.

Methods

Expression of recombinant Na+ channel

Na+ channels were expressed in HEK 293 cells as previously described (Abriel et al., 2001). Transient transfection was carried out with equal amounts of WT or mutant Na+ channel α subunit cDNA with human β1 cDNA subcloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector (Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) along with CD8, a commercially available reporter gene (EBO-pCD vector; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.). Total cDNA was 2.5 μg. WT and mutant Na+ channels were expressed in HEK cells using a previously described lipofection procedure to transfect cells (Abriel et al., 2001). CD8-positive cells, identified using Dynabeads (M-450; Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway), were patch clamped 48 h after transfection.

Transgenic mice and isolation of cardiac ventricular myocytes

Mice heterozygous for a knock-in KPQ deletion in SCN5A, which were kindly provided to us by Peter Carmeliet (Leuven, Belgium), have been described in detail previously (Nuyens et al., 2001). Mice were genotyped by PCR analysis to confirm the expression of the SCN5A ΔKPQ Na+ channels. Adult mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (50 mg kg−1), hearts excised, and single ventricular myocytes dissociated using previously described methods (Powell et al., 1980; Mitra & Morad, 1985) using 87 U ml−1 of collagenase type II (Invitrogen) and 26 U ml−1 of protease type XIV (Sigma, St Louis, U.S.A.). The institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Columbia University approved the protocols for all animal studies.

Voltage–clamp studies

Membrane currents were measured using whole-cell procedures with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Capacity current and series resistance compensation were carried out using analogue techniques according to the amplifier manufacture (Axon Instruments Inc.). All measurements were obtained at room temperature (22°C). Macroscopic whole-cell Na+ current was recorded using the following solutions, shown in mmol l−1. The pipette solution contained 50 aspartic acid, 60 CsCl, 5 Na2ATP, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2, at pH 7.2 adjusted with CsOH. Previous studies have shown that, using this internal solution, time-dependent shifts in sodium channel gating are minimal over at least 12 min recording periods (Abriel et al., 2001). The external solution contained 130 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 5 CsCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5 glucose, at pH 7.4 adjusted with CsOH. For whole-cell recording from murine ventricular myocytes, 0.1 mmoll−1 CoCl2 was added to the external solution to inhibit the L-type calcium channel current. Control experiments showed that CoCl2 at 0.01 mM has no effect on our measurement of peak and sustained Na+ current consistent with previous reports of the effects of CoCl2 in heart (Valenzuela et al., 1995). In experiments designed to test for sustained currents, tetrodotoxin (TTX) was applied at high concentrations (30 μM) to block expressed Na+ channel currents and reveal background currents which were then subtracted digitally. To test the effects of ranolazine, the following procedure was followed. After recording control Na+ channel activity, TTX (30 μM) was applied to determine TTX-sensitive current in control conditions. TTX was then washed off for Na+ channel current recovery. Ranolazine was then washed in and this was followed by a second exposure to TTX to determine TTX-sensitive current in the presence of ranolazine. Ranolazine and TTX were then washed out for recovery of Na+ channel current. As wash in and wash out of both TTX and ranolazine are rapid, this entire procedure was carried out in 8–10 min (Supplementary Figure 1). The two sets of TTX-sensitive currents were then used to determine the effects of ranolazine on sustained and peak currents. Holding potential was −100 mV with a test pulse at −10 mV for 200 ms. Tonic block was measured at frequency of 0.33 Hz after steady state was achieved in the presence of ranolazine (2–4 min). Use-dependent block (UDB) was induced by imposing conditioning trains of 100–300 pulses (−10 mV, 25 ms) from a −100 mV holding potential at frequency of 5 Hz. This was sufficiently long to induce steady-state UDB for each construct. UDB was measured as the ratio of peak current at −10 mV after and before application of a conditioning train and is reported as the percentage block of peak current.

Action potential studies in murine cardiomyocytes

Action potentials were recorded from ventricular myocytes isolated from WT and ΔKPQ mice using whole-cell procedure and the current clamp mode with the following solutions shown in mmol l−1. The internal solution contained 110 KCl, 18 KOH, 5 Na2ATP, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2, at pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH. The external solution contained 132 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 4.8 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 5 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 5 glucose, at pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH. The effect of ranolazine was determined by recording action potentials during pacing at 0.5 Hz.

Action potential simulation studies

Human cardiac myocytes were simulated using the computation model often Tusscher et al. (2004). In order to more accurately reproduce sodium channel kinetics, a Markov model Nav1.5 (Clancy et al., 2002) was utilized with maximal conductance altered to match the maximal current in the human myocytes model. Long QT-3 mutation cells are modeled as possessing a 10-fold increase in the probability of transitioning into the bursting, noninactivating, pathway within the model. Ranolazine blockade was simulated at a therapeutic concentration of 5 μM. A 25% reduction in L-type calcium and IKr channels was modeled at this concentration based on the dose–response curves previously reported (Antzelevitch et al., 2004b) for the channels.

Drugs

Ranolazine (lot # E3-ML-003) was provided by CV Therapeutics Inc. Ranolazine was prepared in water at a final concentration of 0.01 M.

Data analysis

pClamp 8.0 (Axon Instruments Inc.), Excel (Microsoft) and Origin (Microcal Software) were used for data acquisition and analysis. Data are presented as mean values±s.e.m. Two-tailed Student's t-test was used to compare two means; a value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Preferential ranolazine block of sustained current for two LQT-3 mutant channels

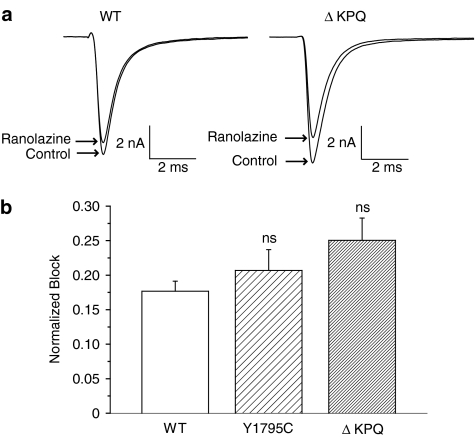

Figure 1 illustrates ranolazine (50 μM) tonic block of peak Na+ channel currents recorded in HEK 293 cells expressing WT and two LQT-3 mutant (Y1795C, ΔKPQ) channels. At this concentration and pulse rate (0.33 Hz), ranolazine modestly blocks the peak current of each construct (illustrated in Figure 1a for WT and ΔKPQ current traces). The average results for multiple cells are shown in the accompanying bar graph (Figure 1b) which indicate no significant differences between ranolazine-induced tonic block of peak Na+ channel current of WT and the two mutant channels.

Figure 1.

Effect of ranolazine on peak sodium current (Ipeak) carried by WT and two disease-associated mutant human sodium channels. (a) Averaged TTX-sensitive traces recorded upon a depolarizing step (200 ms at −10 mV, pulse frequency 0.33 Hz) show currents from HEK 293 cells expressing WT and ΔKPQ sodium channel before and after steady-state block of peak Na+ current by ranolazine (50 μM). (b) Bar graphs summarize the effect of ranolazine on peak Na+ current measured in WT (n=3), Y1795C (n=4) and ΔKPQ channels (n=7). Normalized block was determined as the fraction of the pulse current normalized to control current reduced by the drug. Shown are mean±s.e.m. data. ns, nonsignificantly different from WT.

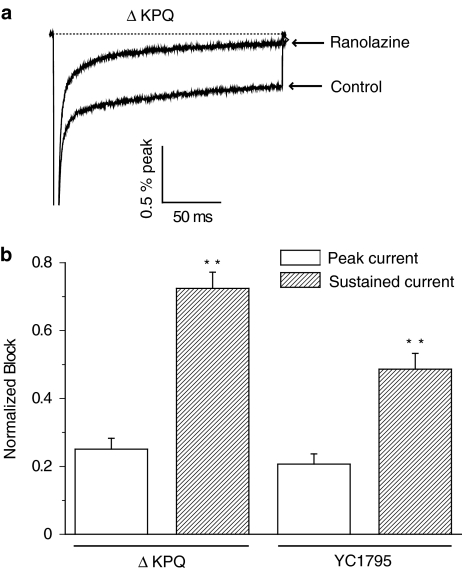

We next tested the effects of ranolazine on Isus, the sustained Na+ current in mutant channels that underlies LQT-3 arrhythmias (Clancy & Rudy, 1999) and compared the effects of ranolazine on both Isus and Ipeak at a common drug concentration (50 μM). Figure 2 shows high-gain recordings (upper panel) obtained from HEK 293 cells expressing ΔKPQ Na+ channels recorded in response to 200 ms depolarizing pulses in the absence and presence of ranolazine. The inward current at the end of the pulse, Isus, is potently blocked at this ranolazine concentration. Peak Na+ current is not observable in the figure because of the high gain used to resolve Isus but the bar graphs summarize ranolazine block of Ipeak (open bars) and Isus (filled bars) for ΔKPQ (left bars) and Y1795C channels (right bars). Ranolazine block of Isus was significantly greater than block of Ipeak for both mutant channels.

Figure 2.

Effect of ranolazine on LQT-3 mutant human sodium channel sustained current (Isus). (a) High gain recordings show averaged sustained Na+ current, normalized to peak Na+ current, and its block by ranolazine (50 μM) for ΔKPQ channels (peak currents are off-scale). (b) Bars summarize the normalized mean block (±s.e.m.) of ranolazine on Isus and Ipeak for two LQT-3 mutant sodium channels: ΔKPQ (n=7) and Y1795C (n=4). **P<0.01 for Ipeak vs Isus.

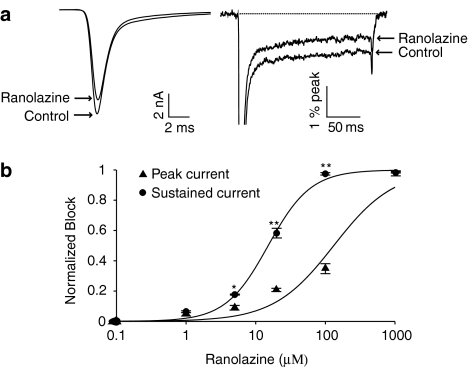

We also determined the effects of ranolazine on peak and sustained Na+ currents measured in myocytes isolated from transgenic mice expressing ΔKPQ sodium channels (Nuyens et al., 2001). This was carried out to examine drug block of ΔKPQ sodium channels in a more physiologically relevant context than the HEK 293 cells expressing Nav1.5 and to allow investigation of the effects of ranolazine on action potentials in myocytes expressing ΔKPQ channels. Figure 3, which summarizes these experiments, shows that in these myocytes as in HEK 293 cells ranolazine preferentially inhibits sustained channel activity. Figure 3a illustrates ranolazine block of peak (left trace) and sustained (right trace, higher gain) Na+ channel currents at a fixed ranolazine concentration (20 μM) and Figure 3b summarizes ranolazine block of peak (triangles) and sustained (circles) Na+ channel currents recorded in ΔKPQ mouse cardiomyocytes over a broad concentration range. The concentration–response curves fitted to the data indicate that ranolazine block of sustained Na+ current is significantly greater than block of peak Na+ current: the IC50 for block of Isus (15 μM) is 9 times greater than the IC50 for block of Ipeak (135 μM). Interestingly, the concentration–response curves indicate that, at a concentration of 50 μM, ranolazine decreased Isus and Ipeak by approximately 85 and 25%, respectively, which is remarkably consistent with the effects of ranolazine at the same concentration on Ipeak and Isus in ΔKPQ HEK cells (Figures 1 and 2). These data, summarized in Table 1, support the hypothesis that ranolazine preferentially blocks sustained vs peak Na+ channel current for the two mutant channels studied, and consequently is expected to abbreviate the action potential in cells with significant sustained Na+ channel current carried by either of these two mutant channels.

Figure 3.

Concentration–response relationships for ranolazine inhibition of peak and sustained sodium current (INa) in ΔKPQ murine cardiomyocytes. (a) Averaged current traces recorded during depolarizing pulses (200 ms, −10 mV, 0.33 Hz) in cardiomyocytes isolated from mice expressing ΔKPQ channels shown at low (left) and high (right) gain before and after steady-state block of peak INa (Ipeak) and sustained INa (Isus) by ranolazine (20 μM). High-gain traces are normalized to peak current. (b) Concentration–response curves of Ipeak and Isus for ΔKPQ myocytes. The averaged data were fitted with the following function: y=A1+((A2–A1)/(1+10^(log10(IC50)–x)*p)) where A1 and A2 are fractional amplitudes of each component, p is the Hill slope and IC50 is the drug concentration that inhibit the response at 50%. IC50 values for Ipeak and Isus are 135 μM and 15 μM, respectively, n=3–5 cells per concentration. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 for Ipeak vs Isus.

Table 1.

Effects of ranolazine on sustained and peak sodium current densities in ΔKPQ mouse cardiomyocytes

| |

Isus(pA/pF) |

Ipeak(pA/pF) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Control |

Ranolazine |

Control |

Ranolazine |

| Ranolazine Concentration (μm) | ||||

| 1 |

−0.9±0.1 |

−0.9±0.2 |

−60.2±6.3 |

−57.2±7.1 |

| 5 |

−1.2±0.4 |

−1±0.4 |

−56.6±4 |

51.1±3.3 |

| 20 |

−1±0.1 |

−0.4±0.1** |

−56.2±7.3 |

−44.3±6.2 |

| 100 |

−0.7±0.1 |

−0.02±0.005** |

−54.2±3.5 |

−35.3±2.7** |

| 1000 | −0.6±0.1 | −0.01±0.0008** | −48.1±5.3 | −1±0.6** |

n=3–5. All values are presented as mean±s.e.m.

P<0.01 ranolazine vs control (paired t-test).

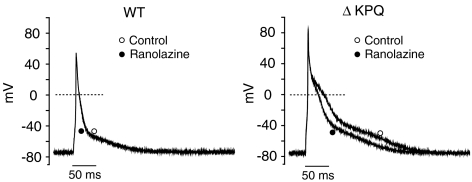

Ranolazine abbreviates APD in myocytes expressing ΔKPQ channels

To test this hypothesis, we recorded action potentials from WT and ΔKPQ mouse ventricular myocytes before and after the application of ranolazine at a pacing rate of 0.5 Hz. Under these conditions ranolazine had little or no effect on action potentials recorded in myocytes isolated from WT murine hearts (Figure 4, left panel), but substantially reduced APD in ΔKPQ mouse cardiomyocytes (Figure 4, right panel). Table 2 summarizes the effects of ranolazine (10 μM) on resting membrane potential (RMP), AP amplitude, AP upstroke velocity and APD to 50% (APD50) and 90% repolarization (APD90) in WT and ΔKPQ myocytes. Under drug-free conditions, the duration of the ΔKPQ AP was significantly (P<0.05) longer than the WT AP as seen in Table 2. These data are consistent with microelectrode studies (Nuyens et al., 2001) and computational models (Clancy & Rudy, 1999) of LQT-3 cellular function. In the presence of ranolazine (10 μM), there were no significant changes in RMP or AP amplitude, or AP upstroke velocity in either WT or ΔKPQ myocytes. However, the drug significantly shortened APD50 and APD90 by 23±5 and 27±3%, respectively, in ΔKPQ myocytes. The drug at the same concentration had no effect on APD50 and APD90 in WT myocytes. Thus, the effects of ranolazine measured on APs in isolated ΔKPQ myocytes are consistent with extrapolation of the voltage–clamp data.

Figure 4.

Effects of ranolazine on the AP in WT and ΔKPQ murine cardiomyocytes. Superimposed APs recorded under control conditions and after addition of ranolazine (10 μM) in WT and ΔKPQ mouse cardiomyocytes stimulated at 0.5 Hz.

Table 2.

Effects of ranolazine on the action potential duration, amplitude, upstroke velocity and resting membrane potential in WT and ΔKPQ mouse cardiomyocytes

| |

WT myocytes |

ΔKPQ myocytes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Ranolazine (10 μM) | Control | Ranolazine (10 μM) | |

| Amplitude (mV) |

119.9±2.6 |

121.5±4 |

139.7±9.5 |

137.1±9.8 |

| RMP (mV) |

−71.9±1.9 |

−71.7±1.9 |

−76.4±0.7 |

−76.5±0.4 |

| APD50 (ms) |

2.7±1.3 |

2.5±1.2 |

16.5±2.8 |

13±3* |

| APD90 (ms) |

18.7±9.9 |

18±9.5 |

85.7±23.3 |

64±19.5* |

| Upstroke (mV ms−1) | 160.8±29.3 | 149±13.5 | 148.6±22.4 | 118.4±21.9* |

RMP indicates resting membrane potential. N=3 for all. All values shown as mean±s.e.m.;

P<0.05 Ranolazine vs control (paired t-test).

Ranolazine interacts with the LA binding site of the sodium channel

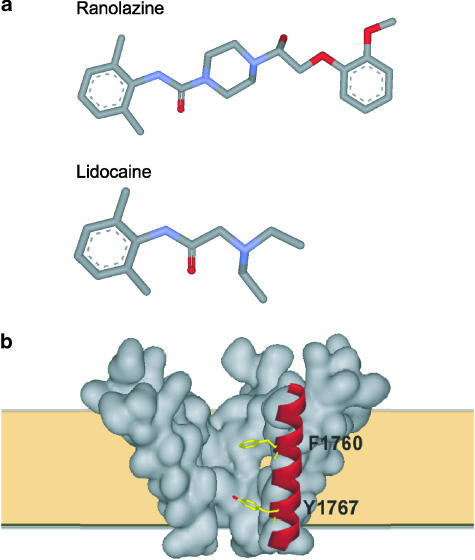

The chemical structures of ranolazine and lidocaine are shown in Figure 5. Like lidocaine, ranolazine presents a typical structure of tertiary amine LA molecule which is composed of hydrophobic (the aromatic ring) and hydrophilic (a tertiary amine) domains separated by an amide linkage. This characteristic structure of lidocaine homologs is a critical determinant in the block of Na+ channels and it has been previously shown that the hydrophobic domain of these molecules strengthens the binding to the Na+ channel while the amine groups block the pore (Zamponi & French, 1994). As a result of the structural similarity of ranolazine and LA molecules and the fact that we and others have previously shown that LA molecules preferentially block sustained current for Y1795C and ΔKPQ mutant channels (Wang et al., 1997; Nagatomo et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2003), we next examined the possibility that ranolazine acts in the same manner as LAs, sharing the receptor site and exhibiting UDB.

Figure 5.

Ranolazine and its structural homology with local anesthetics. (a) Structural comparison of ranolazine and lidocaine (blue color represents nitrogen and red color represents oxygen). (b) Schematic view of sodium channel pore illustrating two key residues (F1760 and Y1767) in the LA binding site in the S6 helical transmembrane segment of domain IV (red).

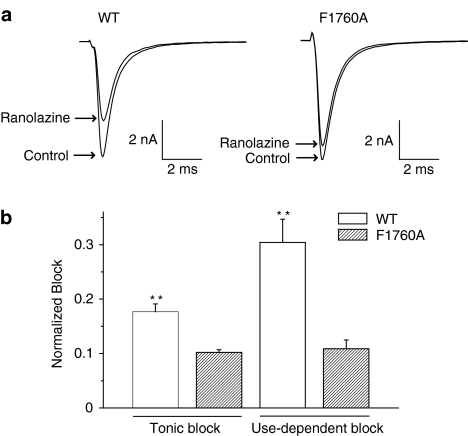

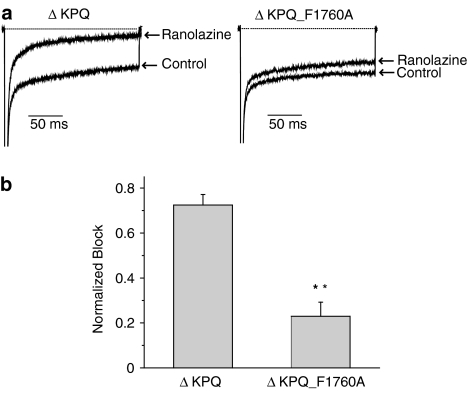

LA molecules bind to a region that lines the inner mouth of the Na+ channel pore. Several key residues that are thought to form part of the receptor for LA molecules have been identified by alanine scanning mutagenesis and two of these key residues (F1760 and Y1767 in Nav1.5) are illustrated in Figure 5b (Ragsdale et al., 1994; 1996; Qu et al., 1995; Linford et al., 1998; Weiser et al., 1999; Yarov-Yarovoy et al., 2001; 2002). We have shown previously that mutation of one of these residues to alanine (F1760A) greatly reduces LA block of LQT-3 and WT Nav1.5 channels (Liu et al., 2003). We thus engineered the F1760A mutation into a background of WT and ΔKPQ channels and tested the effects of ranolazine on these constructs expressed in HEK 293 cells. We previously have shown that under drug-free conditions, the F1760A mutation has little effect on Na+ channel activity but does cause a small positive shift in channel availability (Liu et al., 2003), thus any effects of the mutation on drug block are due to mutation-induced changes in the drug/channel interactions which may be contributed, in part to the mutation-induced change in steady-state availability. Figure 6b summarizes the effects of the F1760A mutation of ranolazine block of peak currents recorded at two stimulation frequencies (0.33 and 5.0 Hz). The F1760A mutation significantly reduces ranolazine block of peak current under both stimulation conditions, similar to the effects of this mutation on block of the same channel constructs by the LAs lidocaine and flecainide (Liu et al., 2003). Figure 7 shows that mutation of the LA receptor binding site similarly and significantly disrupts ranolazine block of sustained Na+ channel current. Thus, these results provide evidence that ranolazine interacts with the LA binding site and, like LA molecules, blocks Na+ channels in a frequency or use-dependent manner preferentially inhibiting persistent Na+ channel activity.

Figure 6.

Mutation of the local anesthetic receptor residue (F1760A) diminishes tonic and UDB of peak sodium channel current by ranolazine. (a) Shown are averaged peak INa recorded at 5 Hz (UDB) in WT and F1760 (see text) channels expressed in HEK 293 cells before and after inhibition of current by ranolazine (50 μM). (b) Bar graphs summarize the fraction of current blocked for tonic block (0.33 Hz) and UDB (5 Hz) measured in WT (n=3 for both tonic block and UDB) and F1760 channels (n=6 for tonic block and n=5 for UDB). Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. **P<0.01 for WT vs F1760A.

Figure 7.

Mutation of the local anesthetic receptor binding site residue (F1760A) diminishes ranolazine block of ΔKPQ channel sustained current. (a) Shown are averaged high-gain current traces recorded in response to 200 ms voltage pulses (−10 mV, 0.33 Hz) before and after exposure to ranolazine (50 μM) recorded in HEK 293 cells expressing ΔKPQ channels and ΔKPQ mutant channels in an α subunit construct harboring the F1760A mutation. (b) The bar graph summarizes the normalized mean ranolazine block of Isus (±s.e.m.) for ΔKPQ (n=7) and ΔKPQ_F1760A (n=6) channels. **P<0.01 for ΔKPQ vs ΔKPQ_F1760A.

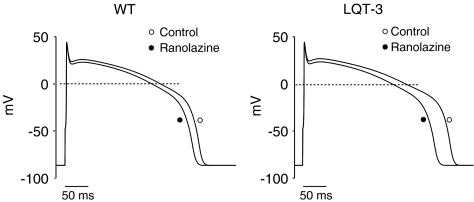

In order to estimate the effects of ranolazine on human ventricular electrical activity, we generated in silico WT and KPQ mutant human cellular action potentials (Methods) and integrated our results obtained in HEK 293 cells and genetically altered murine myocytes into these model cells. Figure 8 illustrates the effects of ranolazine on these simulated action potentials at a drug concentration (5 μM) and heart rate (1 beat s−1) that is relevant to clinical conditions. Under these conditions ranolazine modestly decreases APD of the WT human AP (from 333 to 318 ms, or a 5% reduction, left panel), an effect that is less than half that observed in the in silico ΔKPQ myocytes (368–328 ms or 11% reduction, right panel). These effects on APD are accompanied by modest (7%) reduction in computed AP upstroke velocity. The computations agree qualitatively with both our observed transgenic ΔKPQ mice APs and with results of studies of canine ventricular preparations (Antzelevitch et al., 2004b).

Figure 8.

Simulated effects of ranolazine on APs in human myocytes. Simulated APs obtained in the absence and in the presence of ranolazine (5 μM) in WT and LQT-3 human myocytes. Each AP shown is the 100th AP in a train of APs stimulated at 1 Hz. At this pacing rate, ranolazine decreases the APD by 15 ms in WT cells and 39 ms in LQT-3 mutant cells.

Discussion

Ranolazine preferentially inhibits sustained current in two LQT-3 mutant Na+ channels

The discovery that inherited mutations of the gene coding for the α subunit of the primary heart voltage-gated Na+ channel cause variant 3 of the LQT has demonstrated without question the importance of altered Na+ channel function to control the duration of the cardiac ventricular action potential and hence the QT interval of the electrocardiogram (Moss & Kass, 2005). Investigation of the pharmacology of disease-associated mutant Na+ channels in heterologous expression systems as well as in genetically altered mice has provided unique opportunities to test for pharmacological efficacy of drugs on human heart sodium channels with defects that are directly associated with known human disease (Schwartz et al., 1995; An et al., 1996; Priori et al., 1996; 2000; Abriel et al., 2000; Benhorin et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2002; 2003). We used this approach in the present study to investigate the effects of ranolazine on two LQT-3 mutant channels and found that, as is the case for toxin-induced sustained Na+ channel activity, ranolazine is almost 10 times more potent at blocking mutation-induced sustained channel activity than peak channel activity.

Evidence that ranolazine interacts with the Na+ channel LA receptor

Ranolazine, which is structurally related to lidocaine and other LA molecules, blocks Na+ channel activity in a manner that resembles LA block of Na+ channels: block is use- or frequency dependent (Figure 6). The structural and pharmacological properties of ranolazine suggested to us that the drug might interact with the LA receptor site on the Nav1.5 channel (Ragsdale et al., 1996; Catterall, 2002; Yarov-Yarovoy et al., 2002) motivating us to use mutagenesis of the previously defined LA binding site to test this hypothesis. Several key residues that form part of the receptor for LA molecules have been identified in Nav1.5 but we chose to mutate one residue (F1760) in transmembrane segment IVS6 because we have previously shown that the F1760A mutation potently reduces Na+ channel block by lidocaine as well as tertiary, ionized, and neutral flecainide analogs with little or no effect on the gating of drug-free channels (Liu et al., 2003). As is the case for the other LA molecules, the F1760A mutation markedly reduces Na+ channel block by ranolazine. Our experiments, which show almost identical effects of the F1760 mutation on ranolazine block of both peak and sustained Na+ channel current, provide strong support for a common site of action of ranolazine and LA molecules. Since alanine-scanning mutagenesis indicates that residues in domains III and IV that contribute to the receptor site face the inner pore region of the channel (Ragsdale et al., 1994) and that they may become accessible to the drug molecules as a result of the conformational changes and stabilize drug binding by interactions with charged, hydrophobic, and/or aromatic residues on the drug molecules (Bokesch et al., 1986; Sheldon et al., 1991; Zamponi & French, 1993), differences in efficacy of ranolazine and other LA molecules is very likely a consequence of drug-structure-related restriction to receptor access. This is an important point for future drug development because, although we find a nine-fold selectivity for sustained vs peak Na+ channel current block by ranolazine, it is very likely that this selectivity may be made even greater with ranolazine analogs for which LA receptor site access is modified in a structure-based manner.

Therapeutic potential of ranolazine

Our data indicate that ranolazine displays a higher potency for blocking sustained Na+ current than peak Na+ current in two LQT-3 mutant channels that promote sustained current causally linked to LQT-3 arrhythmias: ΔKPQ and Y1795C mutant Na+ channels (Bennett et al., 1995; Rivolta et al., 2001). Ranolazine preferentially inhibited Isus over Ipeak in a concentration range from 5 to 100 μM (IC50=15 vs 135 μM). This behavior is consistent with the Ls with which ranolazine shares a binding site. The IC50s for blocking sustained and peak current fall within the range of IC50s reported for several Ls including mexiletine (IC50=2–3 μM for Isus and 6.5 μM for Ipeak), lidocaine (IC50=89 μM for Isus and 205 μM for Ipeak) and flecanide (19 μM for Isus and 48–80 μM for Ipeak) (Wang et al., 1997; Dumaine & Kirsch, 1998; Abriel et al., 2000; Nagatomo et al., 2000). The voltage–clamp analysis of drug modulation of peak and sustained current predicts that ranolazine, like other LA molecules, should have greater impact on the cellular action potential plateau (and corresponding QT interval of the ECG) than on action potential upstroke (and corresponding QRS interval on the ECG).

We were able to test this prediction directly by determining the effects of ranolazine on cellular APs measured in murine myocytes expressing LQT-3 mutant channels and in an in silico model of a human myocyte. In this study, we observed that ranolazine, at low concentrations, decreases the duration of AP in mouse ΔKPQ myocytes and simulated human LQT-3 myocytes compared to the AP in WT myocytes. The marked APD reduction was accompanied by a mild reduction in AP upstroke velocity in both myocytes (see Table 2) and simulations. The results that ranolazine markedly reduced the prolongation of the AP in cells with a LQT-3 mutation in the gene SCN5A are consistent with the findings of Song et al. (2004) (Wu et al., 2004) in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes treated with ATX-II, a toxin which increases sustained Na+ current and mimics the effect of a SCN5A gene mutation.

However, extrapolation of our results directly to clinical use must be made with caution. Ranolazine, like the Ls and other antiarrhythmic drugs, possesses a broad nonspecific pharmacological profile and consequently will have complex effects in heterogeneous myocardium. A previous experimental study suggests that this pharmacological profile abbreviates APD in multiple cell types and may reduce dispersion of repolarization (Antzelevitch et al., 2004b) and thus this aspect of ranolazine's actions, in addition to its clear preferential modulation of sustained vs peak Na+ channel activity, may provide for a distinct efficacy of this drug in prevention and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias.

Relevance to other disorders and mutations

Not all LQT-3 mutant channels cause arrhythmias via the same mutation-altered changes in channel gating (Clancy et al., 2003) and not all drugs that block Na+ channels affect mutant channels in the same manner (Liu et al., 2002). Therefore, it could be interesting to determine whether or not the preferential block of arrhythmia-associated activity of the two LQT-3 mutations studied in this work is generalized to other LQT-3 mutations. In addition, the sustained Na+ current studied in this work is related to the rare inherited cardiac disorder, LQT syndrome. Sustained Na+ current is modulated in some cases by protein kinase A- and protein kinase C-dependant pathways (Tateyama et al., 2003a, 2003b) suggesting the possibility that in other, more common cardiac disorders such as heart failure and/or ischemia, sustained Na+ channel current may also prolong APD and QT interval.

Our data clearly indicate that ranolazine interacts with a residue that is known to form the receptor site for L molecules to block potently the Na+-sustained current that underlies LQT-3 arrhythmias. This effect should be due in part to the unique structure of ranolazine, which resembles that of LAs. Future work should be directed at determining the mechanism by which ranolazine blocks Na+ channels both in terms of access to this receptor binding site as well as its dependence on Na+ channel state. Similar studies have clearly shown how other LA molecules such as flecainide and lidocaine dependent on channel openings and transitions into and from the inactivated state to block Na+ channels (Liu et al., 2002), and in addition with this information, modification of drug action based on molecule structural changes is possible (Liu et al., 2003). Thus, with additional experimental work, it is very likely that ranolazine analogs can be synthesized that are designed to optimize inhibition of sustained Na+ current under a variety of pathological conditions. Additionally, it is very possible that pathological conditions that promote enhanced sodium entry into myocytes via the Na+ channel are accompanied by alteration in intracellular calcium homeostasis that, in turn, may contribute to cellular electrical instability and arrhythmogenesis (Abriel et al., 2001). If this indeed turns out to be the case, then the antiarrhythmic efficacy of drugs such as ranolazine may be due, not only to preferential inhibition of sustained Na+ channel current, but to indirect inhibitory effects on other pathways such as L-type calcium channels that contribute to cellular calcium homeostasis. Future work will clearly be focused on this interesting and important possibility.

External data objects

Figure 1 Supplement

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL-56810-08) and from CV Therapeutics.

Abbreviations

- APD

action potential duration

- LA

local anesthetic

- LQT

long QT syndrome

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Pharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/bjp).

References

- ABRIEL H., CABO C., WEHRENS X.H., RIVOLTA I., MOTOIKE H.K., MEMMI M., NAPOLITANO C., PRIORI S.G., KASS R.S. Novel arrhythmogenic mechanism revealed by a long-QT syndrome mutation in the cardiac Na(+) channel. Circ. Res. 2001;88:740–745. doi: 10.1161/hh0701.089668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABRIEL H., WEHRENS X.H., BENHORIN J., KEREM B., KASS R.S. Molecular pharmacology of the sodium channel mutation D1790G linked to the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2000;102:921–925. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AN R.H., BANGALORE R., ROSERO S.Z., KASS R.S. Lidocaine block of LQT-3 mutant human Na+ channels. Circ. Res. 1996;79:103–108. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AN R.H., WANG X.L., KEREM B., BENHORIN J., MEDINA A., GOLDMIT M., KASS R.S. Novel LQT-3 mutation affects Na+ channel activity through interactions between alpha- and beta1-subunits. Circ. Res. 1998;83:141–146. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANTZELEVITCH C., BELARDINELLI L., WU L., FRASER H., ZYGMUNT A.C., BURASHNIKOV A., DIEGO J.M., FISH J.M., CORDEIRO J.M., GOODROW R.J., Jr, SCORNIK F., PEREZ G. Electrophysiologic properties and antiarrhythmic actions of a novel antianginal agent. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004a;9 Suppl 1:S65–S83. doi: 10.1177/107424840400900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANTZELEVITCH C., BELARDINELLI L., ZYGMUNT A.C., BURASHNIKOV A., DI DIEGO J.M., FISH J.M., CORDEIRO J.M., THOMAS G. Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation. 2004b;110:904–910. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139333.83620.5D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENHORIN J., TAUB R., GOLDMIT M., KEREM B., KASS R.S., WINDMAN I., MEDINA A. Effects of flecainide in patients with new SCN5A mutation: mutation-specific therapy for long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2000;101:1698–1706. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENNETT P.B., YAZAWA K., MAKITA N., GEORGE A.L., JR Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995;376:683–685. doi: 10.1038/376683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEZZINA C., VELDKAMP M.W., VAN DEN BERG M.P., POSTMA A.V., ROOK M.B., VIERSMA J.W., VAN LANGEN I.M., TAN-SINDHUNATA G., BINK-BOELKENS M.T., VAN DER HOUT A.H., MANNENS M.M., WILDE A.A. A single Na(+) channel mutation causing both long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circ. Res. 1999;85:1206–1213. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOKESCH P.M., POST C., STRICHARTZ G. Structure–activity relationship of lidocaine homologs producing tonic and frequency-dependent impulse blockade in nerve. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1986;237:773–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CATTERALL W.A. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CATTERALL W.A.Molecular mechanisms of gating and drug block of sodium channels Novartis Found. Symp. 2002241206–218.discussion 218–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAITMAN B.R., PEPINE C.J., PARKER J.O., SKOPAL J., CHUMAKOVA G., KUCH J., WANG W., SKETTINO S.L., WOLFF A.A. Effects of ranolazine with atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem on exercise tolerance and angina frequency in patients with severe chronic angina: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:309–316. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLANCY C.E., KASS R.S. Inherited and acquired vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias: cardiac Na+ and K+ channels. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:33–47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLANCY C.E., RUDY Y. Linking a genetic defect to its cellular phenotype in a cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1999;400:566–569. doi: 10.1038/23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLANCY C.E., TATEYAMA M., KASS R.S. Insights into the molecular mechanisms of bradycardia-triggered arrhythmias in long QT-3 syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:1251–1262. doi: 10.1172/JCI15928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLANCY C.E., TATEYAMA M., LIU H., WEHRENS X.H., KASS R.S. Non-equilibrium gating in cardiac Na+ channels: an original mechanism of arrhythmia. Circulation. 2003;107:2233–2237. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000069273.51375.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMAINE R., KIRSCH G.E. Mechanism of lidocaine block of late current in long Q-T mutant Na+ channels. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:H477–H487. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FABRITZ L., KIRCHHOF P., FRANZ M.R., NUYENS D., ROSSENBACKER T., OTTENHOF A., HAVERKAMP W., BREITHARDT G., CARMELIET E., CARMELIET P. Effect of pacing and mexiletine on dispersion of repolarisation and arrhythmias in DeltaKPQ SCN5A (long QT3) mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;57:1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00839-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRALINSKI M.R., CHI L., PARK J.L., FRIEDRICHS G.S., TANHEHCO E.J., MCCORMACK J.G., LUCCHESI B.R. Protective Effects of Ranolazine on Ventricular Fibrillation Induced by Activation of the ATP-Dependent Potassium Channel in the Rabbit Heart. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996;1:141–148. doi: 10.1177/107424849600100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASS R.S. The channelopathies: novel insights into molecular and genetic mechanisms of human disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1986–1989. doi: 10.1172/JCI26011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINFORD N.J., CANTRELL A.R., QU Y., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Interaction of batrachotoxin with the local anesthetic receptor site in transmembrane segment IVS6 of the voltage-gated sodium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:13947–13952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU H., ATKINS J., KASS R.S. Common molecular determinants of flecainide and lidocaine block of heart na(+) channels: evidence from experiments with neutral and quaternary flecainide analogues. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;121:199–214. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU H., TATEYAMA M., CLANCY C.E., ABRIEL H., KASS R.S. Channel openings are necessary but not sufficient for use-dependent block of cardiac Na(+) channels by flecainide: evidence from the analysis of disease-linked mutations. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002;120:39–51. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOUIS A.A., MANOUSOS I.R., COLETTA A.P., CLARK A.L., CLELAND J.G. Clinical trials update: The Heart Protection Study, IONA, CARISA, ENRICHD, ACUTE, ALIVE, MADIT II and REMATCH. Impact of Nicorandil on Angina. Combination Assessment of Ranolazine in Stable Angina. ENhancing Recovery In Coronary Heart Disease patients. Assessment of Cardioversion Using Transoesophageal Echocardiography. AzimiLide post-Infarct surVival Evaluation. Randomised Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for Treatment of Chronic Heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2002;4:111–116. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANTEGAZZA M., YU F.H., CATTERALL W.A., SCHEUER T. Role of the C-terminal domain in inactivation of brain and cardiac sodium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:15348–15353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211563298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITRA R., MORAD M. A uniform enzymatic method for dissociation of myocytes from hearts and stomachs of vertebrates. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;249:H1056–H1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.5.H1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOSS A.J., KASS R.S. Long QT syndrome: from channels to cardiac arrhythmias. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2018–2024. doi: 10.1172/JCI25537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOTOIKE H.K., LIU H., GLAASER I.W., YANG A.S., TATEYAMA M., KASS R.S. The Na+ channel inactivation gate is a molecular complex: a novel role of the COOH-terminal domain. J. Gen. Physiol. 2004;123:155–165. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGATOMO T., JANUARY C.T., MAKIELSKI J.C. Preferential block of late sodium current in the LQT3 DeltaKPQ mutant by the class I(C) antiarrhythmic flecainide. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;57:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NUYENS D., STENGL M., DUGARMAA S., ROSSENBACKER T., COMPERNOLLE V., RUDY Y., SMITS J.F., FLAMENG W., CLANCY C.E., MOONS L., VOS M.A., DEWERCHIN M., BENNDORF K., COLLEN D., CARMELIET E., CARMELIET P. Abrupt rate accelerations or premature beats cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mice with long-QT3 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1021–1027. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEPINE C.J., WOLFF A.A. A controlled trial with a novel anti-ischemic agent, ranolazine, in chronic stable angina pectoris that is responsive to conventional antianginal agents. Ranolazine Study Group. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999;84:46–50. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POWELL T., TERRAR D.A., TWIST V.W. Electrical properties of individual cells isolated from adult rat ventricular myocardium. J. Physiol. 1980;302:131–153. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRIORI S.G., NAPOLITANO C., CANTU F., BROWN A.M., SCHWARTZ P.J. Differential response to Na+ channel blockade, beta-adrenergic stimulation and rapid pacing in a cellular model mimicking the SCN5A and HERG defects present in the long-QT syndrome. Circ. Res. 1996;78:1009–1015. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRIORI S.G., RONCHETTI E., MEMMI M. Gene specific therapy for arrhythmogenic disorders. Ital. Heart J. 2000;1 Suppl 3:S52–S54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QU Y., ROGERS J., TANADA T., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Molecular determinants of drug access to the receptor site for antiarrhythmic drugs in the cardiac Na+ channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:11839–11843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAGSDALE D.S., MCPHEE J.C., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science. 1994;265:1724–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.8085162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAGSDALE D.S., MCPHEE J.C., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Common molecular determinants of local anesthetic, antiarrhythmic, and anticonvulsant block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:9270–9275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIVOLTA I., ABRIEL H., TATEYAMA M., LIU H., MEMMI M., VARDAS P., NAPOLITANO C., PRIORI S.G., KASS R.S. Inherited Brugada and long QT-3 syndrome mutations of a single residue of the cardiac sodium channel confer distinct channel and clinical phenotypes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30623–30630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ P.J., PRIORI S.G., LOCATI E.H., NAPOLITANO C., CANTU F., TOWBIN J.A., KEATING M.T., HAMMOUDE H., BROWN A.M., CHEN L.S.K. Long QT syndrome patients with mutations of the SCN5A and HERG genes have differential responses to NA+ channel blockade and to increases in heart rate: implications for gene-specific therapy. Circulation. 1995;92:3381–3386. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHELDON R.S., HILL R.J., TAOUIS M., WILSON L.M. Aminoalkyl structural requirements for interaction of lidocaine with the class I antiarrhythmic drug receptor on rat cardiac myocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;39:609–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIMIZU W., ANTZELEVITCH C. Sodium channel block with mexiletine is effective in reducing dispersion of repolarization and preventing torsade des pointes in LQT2 and LQT3 models of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation J1 – Circ. 1997;96:2038–2047. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SONG Y., SHRYOCK J.C., WU L., BELARDINELLI L. Antagonism by ranolazine of the pro-arrhythmic effects of increasing late INa in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2004;44:192–199. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TATEYAMA M., KUROKAWA J., TERRENOIRE C., RIVOLTA I., KASS R.S. Stimulation of protein kinase C inhibits bursting in disease-linked mutant human cardiac sodium channels. Circulation. 2003a;107:3216–3222. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070936.65183.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TATEYAMA M., RIVOLTA I., CLANCY C.E., KASS R.S. Modulation of cardiac sodium channel gating by protein kinase A can be altered by disease-linked mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003b;278:46718–46726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEN TUSSCHER K.H., NOBLE D., NOBLE P.J., PANFILOV A.V. A model for human ventricular tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;286:H1573–H1589. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00794.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALDIVIA C.R., CHU W.W., PU J., FOELL J.D., HAWORTH R.A., WOLFF M.R., KAMP T.J., MAKIELSKI J.C. Increased late sodium current in myocytes from a canine heart failure model and from failing human heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALENZUELA C., SNYDERS D.J., BENNETT P.B., TAMARGO J., HONDEGHEM L.M. Stereoselective block of cardiac sodium channels by bupivacaine in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circulation. 1995;92:3014–3024. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VELDKAMP M.W., VISWANATHAN P.C., BEZZINA C., BAARTSCHEER A., WILDE A.A., BALSER J.R. Two distinct congenital arrhythmias evoked by a multidysfunctional Na(+) channel. Circ. Res. 2000;86:E91–E97. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.9.e91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VISWANATHAN P.C., BEZZINA C.R., GEORGE A.L., JR, RODEN D.M., WILDE A.A., BALSER J.R. Gating-dependent mechanisms for flecainide action in SCN5A-linked arrhythmia syndromes. Circulation. 2001;104:1200–1205. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.093797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG D.W., YAZAWA K., MAKITA N., GEORGE A.L., BENNETT P.B. Pharmacological Targeting of Long QT Mutant Sodium Channels. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1714–1720. doi: 10.1172/JCI119335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Q., SHEN J., SPLAWSKI I., ATKINSON D., LI Z., ROBINSON J.L., MOSS A.J., TOWBIN J.A., KEATING M.T. SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:805–811. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISER T., QU Y., CATTERALL W.A., SCHEUER T. Differential interaction of R-mexiletine with the local anesthetic receptor site on brain and heart sodium channel alpha-subunits. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:1238–1244. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU L., SHRYOCK J.C., SONG Y., LI Y., ANTZELEVITCH C., BELARDINELLI L. Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in a guinea pig in vitro model of long-QT syndrome. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;310:599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAROV-YAROVOY V., BROWN J., SHARP E.M., CLARE J.J., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent gating and binding of pore-blocking drugs in transmembrane segment IIIS6 of the Na(+) channel alpha subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAROV-YAROVOY V., MCPHEE J.C., IDSVOOG D., PATE C., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Role of amino acid residues in transmembrane segments IS6 and IIS6 of the Na+ channel alpha subunit in voltage-dependent gating and drug block. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:35393–35401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAMPONI G.W., FRENCH R.J. Dissecting lidocaine action: diethylamide and phenol mimic separate modes of lidocaine block of sodium channels from heart and skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 1993;65:2335–2347. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81292-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAMPONI G.W., FRENCH R.J. Amine blockers of the cytoplasmic mouth of sodium channels: a small structural change can abolish voltage dependence. Biophys. J. 1994;67:1015–1027. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80567-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZYGMUNT A.C., EDDLESTONE G.T., THOMAS G.P., NESTERENKO V.V., ANTZELEVITCH C. Larger late sodium conductance in M cells contributes to electrical heterogeneity in canine ventricle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;281:H689–H697. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1 Supplement