Abstract

We investigated DNA copy number aberrations in 37 cell lines derived from multiple myelomas (MMs) using comparative genomic hybridization, and 11 (29.7%) showed high-level gain indicative of gene amplification at 1q12-q22. A corresponding transcriptional mapping using oligonucleotide arrays extracted three up-regulated genes (IRTA2, PDZK1, and S100A6) within the smallest region of overlapping in amplifications. Among them PDZK1 showed amplification and consequent overexpression in the MM cell lines. Amplification of PDZK1 was observed in primary cases of MM as well. MM cell lines with amplification of PDZK1 exhibited the resistance to melphalan-, cis-platin-, and vincristin-induced cell death compared with MM cell lines without its amplifications. Furthermore, down-regulation of PDZK1 with an anti-sense oligonucleotide sensitized a cell line KMS-11 to melphalan, cis-platin, and vincristin. Taken together, our results indicate that PDZK1 is likely to be one of targets for 1q12-q22 amplification in MM and may be associated with the malignant phenotype, including drug resistance, in this type of tumor.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a B-cell malignancy that is characterized by the accumulation of plasma cells with a low-proliferation index and an extended life span within the bone marrow. Despite recent improvements in event-free and long-term survival resulting from autologous stem cell transplantation, MM remains a disease with a wide variability of clinical futures, responses to treatment, and survival times among the patients.1

It was observed that virtually all MM patients are chromosomally abnormal.2–8 The primary translocations occur as early and perhaps initiating events during the pathogenesis of MM; and the clustering of rearrangement breakpoints are detected at 14q32, 16q11, and 22q11.8 However, these translocations are not sufficient for the malignant progression of this disease,9,10 and the accumulation of additional genetic alterations affecting tumor-related genes, including proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, are necessary for the emergence of a fully malignant phenotype. Indeed, karyotype analysis and recent fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis indicate that the disease progression of MM correlates with the appearance of secondary nonrandom chromosomal aberrations.7,11

1q rearrangement is one of secondary chromosomal changes associated with malignant phenotype in hematopoietic tumors, such as MM and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.11,12 Previous comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) studies have revealed the gain or amplification of 1q, consistently involving 1q21 in MM.13–15 Gains of 1q can occur as duplications of translocated unbalanced derivative chromosomes, isochromosomes, or jumping translocations.16 In various other tumors, moreover, gain or amplification affecting ∼1q has been reported to appear more frequent in aggressive tumors with malignant potential and resistance to chemotherapy.17–19 In addition, until now, it has been reported as known oncogenes that BCL9, MCL1, ARNT, AF1q, JTB, MUC1, IRTA1, IRTA2, FCGR2B, and PBX1 were up-regulated by the juxtaposition with immunoglobulin (IG) genes or the chromosomal gain involving 1q rearrangement.20–30 Although these circumstances suggested that the region around 1q21 harbors one or more target genes associated with malignant phenotype of MM and other tumors, the critical genetic region and the essential target genes for chromosomal gain involving 1q rearrangement in MM remains obscure.

In the study reported here, we examined 37 MM cell lines by CGH to explore genomic alterations that might affect progression of this disease. Among losses and gains involving several chromosomal regions, we detected high-level gain (HLG) in 1q12-q22 in 29.7% of MM cell lines and defined the smallest region of overlap (SRO) by FISH. Through a corresponding transcriptional mapping using oligonucleotide arrays, PDZK1 (the PDZ domain containing 1) emerged as a candidate target within the SRO. Further, in vitro studies using MM cell lines suggested that PDZK1 might be associated with the resistance to chemotherapeutic reagents in MM.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Primary Samples of MM

All of the 37 human MM cell lines were established from primary samples (see Table 1) and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Primary MM samples from 29 independent patients were provided by the Kawasaki Medical School Hospital, with written consent from each patient in the formed style and after approval by the local ethics committee. Primary samples were composed of 4.7 to 87.0% (mean, 48.9%) tumor cells.

Table 1.

Summary of 37 MM Cell Lines Used in the Present Study

| No. cell lines | Tissue source | Origin | High-level gains (HLGs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 KM-1 | 1q12-q23, 7p14-p15 | ||

| 2 KM-4 | — | ||

| 3 KM-5 | 1q12-q22, 18q22-q23, 20p12-p13 | ||

| 4 KM-6 | 8p22-p23, 8q, 19p13.2-p13.3, 20q | ||

| 5 KM-7 | 1q12-q23, 8q23-q24 | ||

| 6 KM-11 | — | ||

| 7 KMS-5 | MM | — | |

| 8 KMS-11 | MM | 1q12-q21 | |

| 9 KMS-18 | MM | — | |

| 10 KMS-20 | 1q12-q22 | ||

| 11 KMS-24 | — | ||

| 12 KMS-26 | 12p11-p12, 16q23-q24 | ||

| 13 KMS-27 | — | ||

| 14 KMS-34 | 7q31-q16 | ||

| 15 KMS-12PE | PE | MM | 3q26.3-q29 |

| 16 KMS-12BM | BM | MM | 13q33-q34 |

| 17 KMS-21PE | PE | MM | — |

| 18 KMS-21BM | BM | MM | — |

| 19 KMS-28PE | 7q31-q16 | ||

| 20 KMS-28BM | — | ||

| 21 MOLP-2 | PB | MM | 1q12-q22 |

| 22 MOLP-5 | PB | MM | — |

| 23 MOLP-6 | PB | MM | — |

| 24 ILKM-2 | BM | MM | — |

| 25 ILKM-3 | BM | — | |

| 26 ILKM-8 | 1q12-q23, 17q21 | ||

| 27 ILKM-10 | — | ||

| 28 ILKM-12 | 7p, 7q | ||

| 29 ILKM-13 | 1q12-q23, 20p12-p13 | ||

| 30 U266 | BM | MM | — |

| 31 AMO1 | PLC | 1q12-q21, 2p24-p25 | |

| 32 L363 | PB | PCL | 1q12-q23, 19p13.2-p13.3 |

| 33 OPM-2 | PB | PCL | — |

| 34 KMM1 | MM | — | |

| 35 KHM-4 | MM | 1q12-q23 | |

| 36 HS | 7q31-q32, 16q22-q23 | ||

| 37 RPMI8226 | PB | PCL | — |

PE, pleural effusion; BM, bone marrow; PB, peripheral blood; MM, multiple myeloma; PLC, plasma cell leukemis; PCL, plasmacytoma.

CGH Analysis

CGH was performed using directly fluorochrome-conjugated DNA as described by Kallioniemi and colleagues,31 with minor modification.32 Briefly, tumor DNAs and normal DNAs were labeled, respectively, with Spectrum Green-dUTP and Spectrum Orange-dUTP (Vysis, Chicago, IL) by nick translation. Labeled tumor and normal DNAs, together with 10 μg of Cot-1 DNA, were denatured and hybridized to normal male metaphase chromosome spreads. The slides were washed and counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole.Shifts in CGH profiles were rated as gains and losses if they reached at least the 1.2 and 0.8 thresholds, respectively, as described elsewhere.32 Overrepresentations were considered to be HLGs, when the fluorescence ratio exceeded 1.5, as described elsewhere.32

FISH Analysis

Metaphase chromosome slides were prepared and used in FISH experiments in the manner described previously.33 The location of each bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) within the region of interest was complied from information archived (on April 2003) by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and confirmed or modified according to the results of FISH using normal metaphase chromosomes. Probes were labeled with biotin-16- or digoxigenin-11-dUTP by nick translation (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan). Chromosomal in situ suppression hybridization and fluorescent detection of hybridization signals were performed as described elsewhere.33 The copy number and molecular organization of the region of interest were assessed according to the hybridization patterns observed on both metaphase and interphase chromosomes.

Preparation of Labeled Probes and Hybridization on Oligonucleotide Arrays

AceGene (Human oligo chip 30K; Hitachi Software Engineering Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan) containing 30,000 genes was used for mRNA expression profiling. We obtained information for each gene on the chips from the NCBI database, and the experiments for the oligonucleotide microarray were performed according to themanufacturer’s instruction (http://dnasis.hskbio.hitachi-sk.co.jp/acegene/). In brief, cDNA probes labeled with aminoallyl-dUTP (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) were synthesized using Oligo(dT)12-18 primer and SuperScript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen K K., Tokyo, Japan). The labeled test and reference cDNA probes were coupled with Cy3- and Cy5-monoreactive dye (Amersham Biosciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan), respectively, and were purified using microbio-spin columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Tokyo, Japan). AceGene arrays were hybridized with the labeled test and reference cDNA probes (cDNA synthesized from 50 μg of total RNA/Chip) for 16 hours at 42°C. After being washed with 2× standard saline citrate and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 minutes at 30°C, 2× standard saline citrate for 5 minutes at 30°C, and 1× standard saline citrate for 5 minutes at 30°C, the hybridized chips were scanned using GenePix 4000B (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, CA), and the digitized image data were processed using version 4.1 GenePixPro software (Axon Instruments Inc.).

Separate images were acquired for Cy3 and Cy5. Each spot was defined by manual positioning of a grid of circles over the array image. For each fluorescent image, the average pixel intensity within each circle was determined, and a local background was computed for each spot equal to the median pixel intensity in a square of 40 pixels in width and height centered on the spot center, excluding all pixels within any defined spots. Net signal was determined by subtraction of this local background from the average intensity for each spot. Spots deemed unsuitable for accurate quantification because of array artifacts were manually flagged and excluded from further analysis. Signal intensities between the two fluorescent images were normalized by the averaged values for blank spots. This effectively defined the signal intensity-weighted spot for the internal controls of housekeeping genes on each array to have a Cy3/Cy5 ratio of 1.0.

Semiquantitative Expression Analysis of Eight Candidate Targets within 1q21-q22 Amplification

A semiquantitative expression analysis was performed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in eight up-regulated genes that emerged within the 1q12-q22 amplification through oligonucleotide microarray analysis. Sequences of primer pairs for each gene examined are available on request. Single-stranded complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated from total RNA of MM cell lines using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s directions. The optimal annealing temperature cycle numbers were determined by performing pilot PCR. PCR products were electrophoresed in 3% agarose gel, and the band quantification was done with LAS-3000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantification of Expression of mRNA and DNA Copy Number of PDZK1

Quantifications of expression level of PDZK1 mRNA were examined by a real-time quantitative PCR in anti-sense experiments.34 DNA copy number of PDZK1 in primary cases of MM was also determined by a real-time quantitative PCR as described.35 Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics) with SYBR Green according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primer-pairs for PDZK1 are follows; forward 5′-CCCACAGTACAGCCTCACATT-3′: reverse 5′-CACATGGTGAATGGTTTCCA-3′, The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene was the endogenous control (Roche Diagnostics) for mRNA expression levels. Level of mRNA expression in each sample was normalized on the basis of the corresponding GAPDH level, and recorded as a relative expression level. β-globin (HBB) served as the endogenous control for genomic DNA copy number analysis. HBB, which is located at 12q13 and rarely involved in MM, either in our panel or in previous studies,13–15 served as the endogenous control for genomic DNA copy number. Copy number in each tumor sample was normalized by dividing it by the corresponding HBB value, and recorded as copy number ratios. Duplicate PCR amplification was performed for each sample.

Assessment of Drug Sensitivity and the Effect of Anti-Sense Oligonucleotide (ASO) Treatment

Melphalan (MEL), cis-platin (cDDP), vincristin (VCR), dexamethasone (DEX), adriamicin (ADM), mitoxantrone (MIT), daunorubicin (DNR), and thalidomide (THAL) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Sensitivity of each MM cell line to those chemotherapeutic/cytotoxic reagents-induced cell death was assessed using a colorimetric assay on microtiter plates (Cell-Counting Kit-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan), which measures the ability of viable cells to cleave a tetrazolium salt (WST-8) to a water-soluble formazan. In brief, MM cells of 3 × 104 in 96-well plates were exposed to various concentrations of reagents for 48 hours. WST-8 was added 2 hours before the end of culture, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Benchmark, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Experiments were repeated three times, and each series was performed in triplicate.

Anti-sense experiments were performed as described previously,34 with minor modifications. Briefly, we synthesized the following oligonucleotides containing phosphorothioate backbones (oligonucleotide phosphorothioate; Espec Oligo Service Co., Tsukuba, Japan): PDZK1-AS; 5′-CTGTACCTCTTTGATGAATG-3′ (the anti-sense direction of PDZK1 cDNA nucleotide 1308 to 1327; GenBank accession number NM_002614), PDZK1-SC; 5′-GTAAGTAGTTTCTCCATGTC-3′ (the scramble control for PDZK1-AS1). Oligonucleotides were delivered into cells using oligofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Treatment with chemotherapeutic reagents was started 24 hours after transfection of oligonucleotides, and viable cell number was assessed 48 hours after treatment (72 hours after transfection) using a colorimetric assay as described above. Experiments were repeated twice, each performed in triplicate.

Results

DNA Copy Number Aberrations Detected by CGH in MM Cell Lines

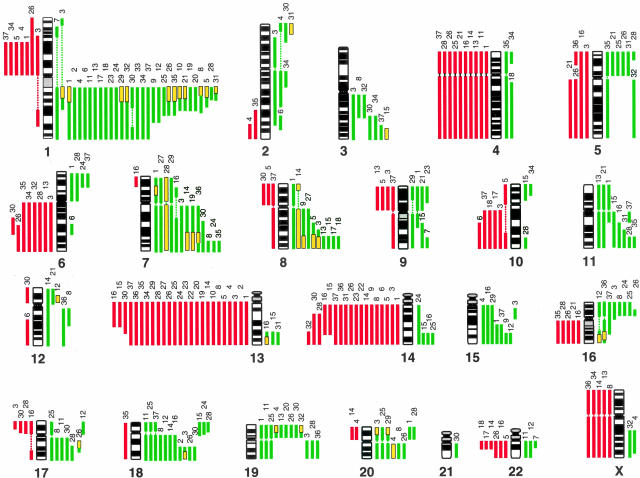

An overview of the genetic changes we detected among 37 MM cell lines is shown in Figure 1. All of lines showed detectable copy number aberrations. The average number of aberrations per cell line was 9.3 (range, 1 to 23); average numbers of gains and losses were 5.6 (range, 0 to 14) and 3.8 (range, 0 to 11), respectively. The minimal common regions of gains that were most frequently involved were at: 1q12-q24 (31 of 37, 83.8%), 7q31-q36 (13 of 37, 35.1%), 18q22-q23 (11 of 37, 29.7%), 8q23-q24 (10 of 37, 27.0%), 19p (9 of 37, 24.3%), and 16p12.1-p12.2 (8 of 37, 21.6%). The most common losses were observed at: 13q14-q32 (25 of 37, 67.6%), 14q22-q24 (17 of 37, 45.9%), 4p and 4q (10 of 37 each, 27.0%), and 6q22-q23 (8 of 37, 21.6%) (Figure 1, Table 1). The smallest regions of HLGs were seen at 1q12-q21 (11 of 37, 29.7%), 7q31-q32, and 8q23-q24 (4 of 37, 10.8% each) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of genetic imbalances detected by CGH in 37 MM cell lines. The 22 autosomes and X chromosome are represented by ideograms showing G-banding patterns. As judged by the computerized green-to-red profiles, vertical lines on the left (red) of each chromosome ideogram show losses of genomic material in cell lines, whereas those on the right (green) correspond to copy number gains. HLGs are represented as yellow rectangles. The number at the top of each vertical line corresponds to the cell line in which each change was recorded (see Table 1).

Definition of 1q HLG Region in MM Cell Lines

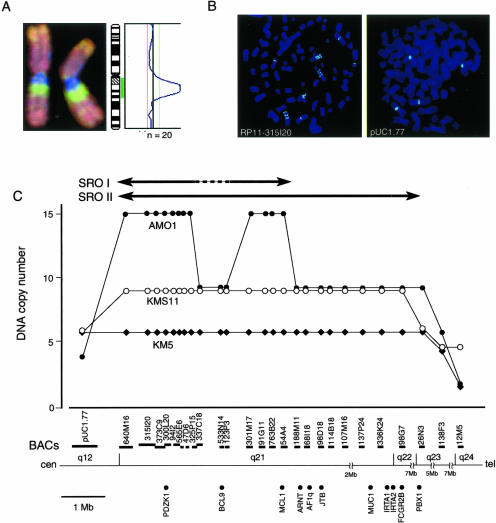

We further focused on the HLG region (Table 1 and Figure 1) at 1q12-q24, because it was most frequently involved. To define the SRO for HLG at 1q12-q24, we performed FISH analysis in three MM cell lines (AMO1, KMS-11, and KM-5) that had exhibited copy number gains with the highest intensity and the narrowest regions in CGH analysis (Figure 1 and Figure 2A). We selected 26 BACs covering 1q21–1q24 and a pUC1.77 at 1q12 as probes for the FISH experiments (Figure 2, B and C). Twelve BACs (640M16, 315I20, 373C9, 300L20, 94I2, 565E6, 47D6, 325P15, 301M17, 91G11, 763B22, and 54A4) produced high copy signals as 15 copies in AMO1 cell line (Figure 2, B and C). Notably, three BACs (337C18, 533N14, and 123P3) located between 325P15 and 301M17 were nine copies in the same cell line (Figure 2, B and C). However, in other two cell lines (KMS-11 and KM-5), the larger (∼20 Mb) regions showing the high-level and constant copy number gains (KMS-11; nine copies, KM-5; six copies) between pUC1.77 and 26N3 (KMS-11) or 138F3 (KM-5) were observed (Figure 2C). Therefore, the SRO could be defined between pUC1.77 and 188M11 (SRO-I; 5 Mb, 1q12-q21.1) as the most HLG region in AMO1, except for 337C18, 533N14, and 123P3, or else between pUC1.77 and 26N3 (SRO-II; ∼20 Mb, 1q12-q22) if we consider the high-level and constant copy number gains of large chromosomal unit in KMS-11 and KM-5, and might include the target genes associated with malignant phenotype of MM.

Figure 2.

Amplicon map of the 1q12-q22 region in MM cell lines. A: Representative CGH image of chromosome 1 of AMO1 cell line showing distinct amplification on the 1q12-q22 region (left) and the corresponding green (gain) and red (loss) profile (right). B: Representative images of FISH analysis on metaphase chromosomes from AMO1 cells. The images show 15 copies with RP11-315I20 (1q21, left) and four copies with pUC1.77 (1q12-specific probe, right). C: Summarized results of DNA copy number analysis at 1q12-q24 by FISH in three different cell lines. The vertical axis shows the number of FISH signals achieved with the BAC probes indicated as horizontal bars. The SRO with the maximal amplification was defined between pUC1.77 and RP11-188M11, except RP11-337C18, RP11-533N14, and RP11-123P3 (SRO-I), or between pUC1.77 and RP11-26N3 (SRO-II) if the change of copy number is considered as common chromosomal gain, and these are indicated by closed arrow. The position and length of each BAC were compiled from information archived by NCBI. The position of each known oncogenes was also listed on the bottom.

Expression Profile on 1q12-q22

To explore the up-regulated genes within the SRO, a corresponding transcriptional mapping using oligonucleotide array on 1q12-q22 was performed in two MM cell lines, AMO1 and KMS-11, both of which showed HLG indicative of gene amplification at 1q12-q22. A mRNA from Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell line established from a healthy male volunteer was used as a reference.36 In those experiments, information for 219 genes spanning the SRO-II region at 1q12-q22 was obtained from the NCBI database. When twofold changes were considered significant in AMO1, 31 of 219 genes were detected as up-regulated genes. Of them eight (six known genes; KCNN3, SLC27A3, IRTA2, PDZK1, S100A6, and SPAP1, and two unknown genes; FLJ22530 and FLJ23221) were up-regulated in both AMO1 and KMS-11 (Table 2). Although there were nine known cancer-related genes (BCL9, MCL1, ARNT, AF1q, JTB, MUC1, FCGR2B, IRTA1, and PBX1) located within the SRO-II (Figure 2C), none of them was detected as an up-regulated gene in our oligonucleotide arrays (it was not available for only IRTA1 in oligonucleotide arrays).

Table 2.

Gene Expression Profile of the 1q12-21 Region for Cell Lines with High-Level Copies

| No. | Symbol | Genbank (Acc. no.) | Gene name | Fold change (/LCL)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMO1 | KMS-11 | ||||

| 1 | HAX1 | NM_006118 | hs1 binding protein | 13.50 | 1.52 |

| 2 | KCNN3* | NM_002249 | Potassium intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily, member 3 | 12.67 | 2.22 |

| 3 | FLJ14225 | NM_024874 | Hypothetical protein | 11.15 | 1.23 |

| 4 | FLJ12528 | NM_025150 | Hypothetical protein | 10.29 | 1.36 |

| 5 | SLC27A3* | NM_024330 | Solute carrier family 27 | 9.43 | 3.70 |

| 6 | C1orf2 | NM_006589 | Chromosome 1 open reading frame 2 | 8.61 | 0.96 |

| 7 | PP591 | NM_025207 | Hypothetical protein | 6.96 | 1.66 |

| 8 | CLK2 | NM_003993 | cdc-like kinase 2 isoform hclk2 | 6.94 | 1.52 |

| 9 | SELENBP1 | NM_003944 | Selenium-binding protein 1 | 6.31 | 1.70 |

| 10 | FY | NM_002036 | Duffy blood group | 4.67 | 1.11 |

| 11 | FCGR1A | NM_000566 | Fc fragment oFigG, high affinity 1a, receptor for (CD64) | 4.33 | 1.03 |

| 12 | FLJ22530* | XM_016470 | Hypothetical protein | 4.05 | 2.04 |

| 13 | IRTA2* | AF343663 | Immunoglobulin superfamily receptor translocation associated protein 2b | 4.00 | 3.95 |

| 14 | CTSK | NM_000396 | Cathepsin k (pycnodysostosis) | 4.00 | 1.66 |

| 15 | LASS2 | NM_013384 | LAG1 longevity assurance homolog 2 | 3.57 | 0.80 |

| 16 | GBA | NM_000157 | Glucosidase, beta; acid (includes glucosylceramidase) | 3.50 | 1.45 |

| 17 | S100A12 | NM_005621 | S100 calcium-binding protein A12 | 3.48 | 1.11 |

| 18 | FLJ23221* | NM_024579 | Hypothetical protein | 3.43 | 2.08 |

| 19 | PDZK1* | NM_002614 | pdz domain containing 1 | 3.24 | 2.00 |

| 20 | NTRK1 | NM_002529 | Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 1 | 3.04 | 1.07 |

| 21 | PIAS3 | NM_006099 | Protein inhibitor of activated stat3 | 3.01 | 0.63 |

| 22 | SLC39A1 | NM_014437 | Solute carrier family 39 (zinc transporter), member 1 | 3.00 | 1.46 |

| 23 | S100A3 | NM_002960 | S100 calcium-binding protein A3 | 2.88 | 1.18 |

| 24 | PDE4DIP | NM_014644 | Phosphodiesterase 4D interacting protein (myomegalin) | 2.76 | 0.97 |

| 25 | SPRR2C | NM_006518 | Small proline-rich protein 2C | 2.37 | 1.20 |

| 26 | S100A6* | AL162258 | S100 calcium-binding protein A6 | 2.33 | 2.03 |

| 27 | LY9 | AF244129 | Lymphocyte antigen 9 | 2.33 | 1.50 |

| 28 | TXNIP | NM_006472 | Thioredoxin interacting protein | 2.23 | 1.08 |

| 29 | NESCA | NM_014328 | New molecule containing SH3 at the carboxy-terminus | 2.22 | 1.21 |

| 30 | VPS45A | NM_007259 | Vacuolar protein sorting 45A | 2.13 | 1.03 |

| 31 | SPAP1* | AF356276 | SH2 domain containing phosphatase anchor protein 1 | 2.00 | 7.35 |

Overexpressed genes in both AMO1 and KMS-11.

LCL, Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell line.

Correlation between Copy Number and Expression of PDZK1 in MM Lines

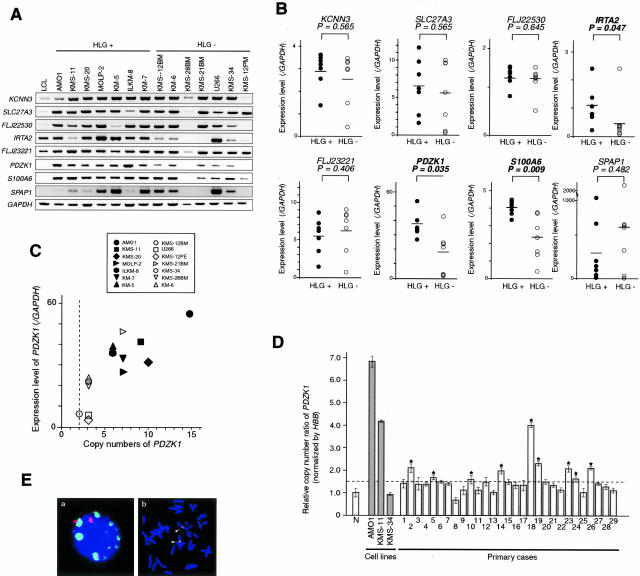

We first confirmed an increase of expression level of eight candidate targets by semiquantitative RT-PCR in two panels consisting of seven MM lines with or without HLG at 1q12-q21, respectively. Among those eight genes, IRTA2, PDZK1, and S100A6 showed the significant difference on expression level between MM cell lines with and without HLG (Figure 3, A and B). However, the up-regulation of IRTA2 in both AMO1 and KMS-11, compared with the lymphoblastoid cell line, did not show in conflict with oligonucleotide array analysis (Figure 3A). Of them, PDZK1 was a notable candidate positionally and functionally, since the previous report disclosed the relevance of this gene to drug resistance37 and further multiplication of 1q harboring PDZK1 was suggested to be associated with drug resistance in ovarian cancer.19 Thus we further examined copy number status and expression levels of PDZK1 in MM cell lines. As shown in Figure 3C, PDZK1 copy numbers determined by FISH were positively correlated with their expression levels; seven cell lines with HLG of PDZK1 (AMO1, 15 copies; KMS-20, 10 copies; KMS-11, 9 copies; MOLP-2, 7 copies; ILKM-8, 6 copies; KM-7, 6 copies; and KM-5, 6 copies) and KMS-21BM (7 copies), which showed PDZK1 amplification in fact copy number by FISH, although it did not show HLG at 1q12-q21 by CGH (Figure 1, Table 1), showed higher expression levels of these genes compared with those without HLG (KMS-34, three copies; KMS-12PE, three copies; U266, three copies; KMS-12BM, two copies; KMS-28BM, two copies; HS, three copies; and KM-6, three copies).

Figure 3.

Correlation between copy number and expression level of PDZK1 in MM cell lines and copy number in primary MM. A: Semiquantitative RT-PCR of eight candidate genes was performed in each panel of seven MM cell lines with HLGs or without HLGs, respectively. Lymphoblastoid cell line was used as the control. Signal intensity was quantified with LAS-3000. B: Correlation between HLGs and relative expression levels was determined on eight candidate genes by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test. IRTA2, PDZK1, and S100A6 revealed a significant difference between HLG(+) and HLG(−). Median values are indicated with horizontal bars. Black or white circles are cell lines with HLG(+) or without HLG(−), respectively. C: DNA copy numbers were determined by FISH using a BAC of PDZK1. Although KMS-21BM never did show in HLG at 1q12-22 by CGH and listed in the group of HLG(−) in Table 1 and Figure 3A, PDZK1 copy number unambiguously showed seven copies. The relative expression levels of each cell line were determined in B. D: Copy number ratios of PDZK1 in 29 primary cases of MM determined by real-time quantitative PCR. The abundance of the PDZK1 gene in genomic DNA of each sample was normalized by the corresponding endogenous control HBB value, and recorded as copy number ratio. DNAs from five independent healthy volunteers were used as normal controls (N). Notably, the copy number ratios for three different MM cell lines determined by a real-time quantitative PCR were clearly correlated with the copy numbers determined by FISH analysis (copy number ratio in real-time PCR versus copy number in FISH: AMO1, 6.9 versus 15; KMS-11, 4.1 versus 9; and KMS-34, 0.8 versus 3, respectively). Bar, the mean ± SD of normal controls and samples. Line, the mean + 2 SD indicating cutoff ratio for copy number gain. E: Amplification of PDZK1 in one case of primary MM by FISH. Green signal of PDZK1 (BAC;RP11-373C9) was clearly amplified, as compared to red signal for pUC1.77 (1q12-specific probe) used as the control (a). Green and red signals were co-localized in 1q12-q21 on metaphase chromosomes from normal peripheral lymphocytes (b).

Frequent Copy Number Gain of PDZK1 in Primary MM Samples

DNA copy number of PDZK1 in primary cases of MM was determined by a real-time quantitative PCR using genomic DNA obtained from 29 patients. As the normal control of diploid copy number, we first determined the copy number ratio of PDZK1 normalized with HBB in DNA derived from five independent healthy volunteers. To separate cases with or without copy number gain, the mean + 2 SD of copy number ratio of PDZK1 in normal controls was used as the cutoff ratio. As shown in Figure 3D, the copy number gain of PDZK1 was detected in 9 of 29 cases (31%), even though primary samples contains only 4.7 to 87.0% (mean, 48.9%) tumor cells. Notably PDZK1 copy number ratio of KMS-11 cell line determined by a real-time quantitative PCR was similar to that of case 18 (copy number ratio = 4.08), from which KMS-11 cell line had been established (Figure 3D). Furthermore we confirmed that PDZK1 copy number ratios for three different MM cell lines determined by real-time quantitative PCR were clearly correlated with PDZK1 copy numbers determined by FISH analysis (copy number ratio in real-time PCR versus copy number in FISH: AMO1, 6.9 versus 15; KMS-11, 4.1 versus 9; and KMS-34, 0.8 versus 3, respectively). These results indicate that the PCR-based method can evaluate genomic copy number change quantitatively, and the amplification of this region is not the artifact acquired during or after the establishment of cell lines. Indeed, significant amplification of PDZK1 could be really observed in one patient with MM by FISH as shown in Figure 3E.

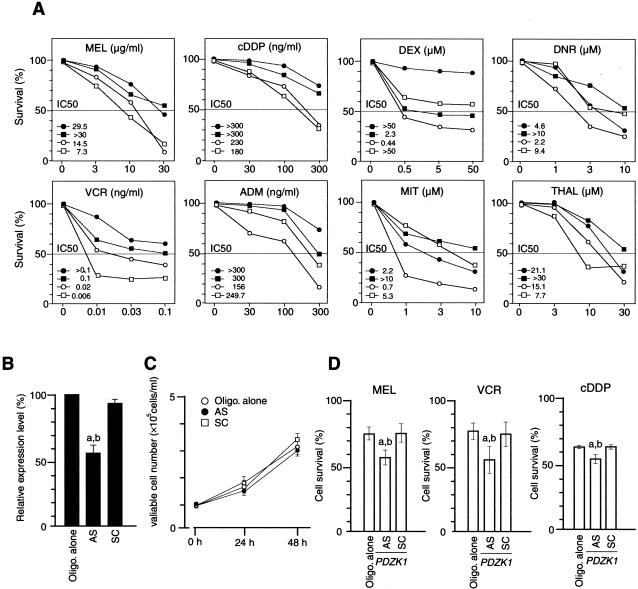

Overexpression of PDZK1 Contributes to the Resistance to Chemotherapeutic Reagent-Induced Cell Death

We next investigated the correlation between the overexpression of PDZK1 affecting copy number gain and the sensitivity to various chemotherapeutic reagents in MM cell lines. Cell lines with the copy number gain and overexpression of PDZK1, AMO1, and KMS-11, were more resistant to the cytotoxic effect of MEL, cDDP, and VCR compared with those without their copy number gain and overexpression, KMS-34 and KMS-12PE (Figure 4A). Whereas, all four cell lines showed no correlation between the overexpressions and the sensitivities to DEX, ADM, MIT, DNR, or THAL (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Effect of various chemotherapeutic/cytotoxic reagents to MM cells with 1q12-q22 amplification. A: The dose-response curves to melphalan (MEL)-, cis-platin (cDDP)-, vincristin (VCR)-, dexamethasone (DEX)-, adriamycin (ADM)-, daunorubicin (DNR)-, mitoxantrone (MIT)-, and thalidomide (THAL)-induced cell death in the 1q12-q22-amplified cell lines, AMO1 (•) and KMS-11 (▪), and the nonamplified cell lines, KMS-34 (○) and KMS-12PE (□). Cell viability was assessed by microtiter plate colorimetric assay. Each point indicates the average value for three separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. A 100% corresponds to the average value in the absence of any drug (vehicle alone). IC50 value of each cell line to each reagent was shown. B: Specific down-regulation of mRNA expression level of PDZK1 or by ASO. Cells were transfected with ASO (AS), oligofectamine alone (Oligo. alone), or the control oligonucleotide (SC). The quantification of mRNA levels was determined 24 hours after transfection by a real-time quantitative PCR. Bars, SD. a, P < 0.05 versus Oligo. alone; b, P < 0.05 versus SC. C: Effect of ASO on cell growth of KMS11 was investigated. In brief, 1 × 105 cells were plated in 24-well plates and after 24 or 48 hours of transfection in absence of drugs, viable cell numbers were determined by hemacytometer cell counts using trypan blue. Bar, the mean ± SD. D: The KMS-11 cells treated by PDZK1-ASO were incubated in the presence or absence of each drug (MEL, 10 μg/ml; VCR, 0.01 ng/ml; and cDDP, 300 ng/ml) for 48 hours. Each value indicates the average for three separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. A 100% corresponds to the average value in the absence of any drug (vehicle alone). Bars, SD. a, P < 0.05 versus Oligo. alone; b, P < 0.05 versus SC.

To test whether the PDZK1 is responsible for the resistance to chemotherapeutic reagent-induced cell death in MM cells, the effect of down-regulation of PDZK1 expression was investigated in MM cell line having HLGs of 1q12-q22 region using anti-sense technique. ASO for PDZK1 delivered into KMS-11 cells inhibited mRNA expression of this gene efficiently (Figure 4B), whereas the control oligonucleotide (PDZK1-SC) did not affect the PDZK1 expression level. We confirmed that there was no effect of ASO on cell growth of KMS-11 in the absence of drugs after its transfection (Figure 4C). PDZK1-AS-treated KMS-11 cells were more sensitive to MEL-, VCR-, or cDDP-induced cell death compared with oligofectamine alone (Oligo. alone) or PDZK1-SC-treated cells (Figure 4C), suggesting that PDZK1, activated through copy number gain, may be at least one of the molecules responsible for drug resistance in MM cells.

Discussion

CGH analysis is a useful method to define regions of genomic gain/amplification and deletion in tumors with a low-proliferative fraction, including MM, which limits generation of evaluable metaphases. Karyotyping and CGH analyses have identified partial or whole1q gain (consistently involving 1q21) in 40 to 60% of MM.13–15 In the study reported here, our CGH analysis also frequently detected the partial or whole gains of 1q in 30 of 37 MM cell lines (83.8%), consistent with previously reported CGH studies (Table 1 and Figure 1). Besides the high frequency, gain/amplification around 1q21 is of quite interest, because the high prevalence of abnormalities involving this region has been observed in multiple tumor types and this aberration may be associated with tumor evolution and/or responsiveness to therapy in those tumors.17–19 Gain/amplification around 1q21 region was related to a highly aggressive phenotype with metastatic potential in osteosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the lung17,18 and with a drug-resistant phenotype in ovarian cancer.19 In addition, patients with osteosarcoma showing 1q21 amplification have a tendency toward shorter survival.18 These pieces of evidences suggested the existence one or more genes could contribute to acquisition of malignant phenotypes necessary for progression of MM and other tumors. Thus we further performed molecular cytogenetic and functional characterization for the chromosomal gains of 1q12-q22 region in MM cells.

We determined the critical region for HLG of 1q12-q22 in MM by FISH analysis using 26 BAC clones, and detected more narrowed HLG region only in AMO1 cell line as SRO-I (Figure 2C). However, in KMS-11, KM-5, and the other 17 MM cell lines we investigated by FISH, it was no evidence for selectively more narrowed HLG region like in AMO1 (Figure 2, B and C, and data not shown). Therefore, we considered that SRO-II was the most frequently and commonly amplified region at 1q in our series of MM cell lines. Further, it has been reported that FISH analysis in MM patients showed the breakages in 89% of cases with 1q breaks and 1q rearrangements, which were all unbalanced (translocations or duplications), leading to generate the aberrant heterochromatin/euchromatin junctions and gain of 1q materials in a majority of cases.11 Consistent with those previous findings, the derivative chromosomes resulting in duplications and breakages with region between 1q12 and 1q21 were observed in FISH analysis for AMO1, KMS-11, KM-7, and KMS-20 (Figure 2, B and C, and data not shown).

The gene expression profiling of MM cell lines with chromosomal gain at 1q12-q22 could provide the novel and valuable information about candidate oncogenes involving chromosomal gains of this region. We identified three up-regulated genes in MM cell lines with HLGs of 1q12-q22. Among them, PDZK1 was identified within SRO-I, where it was the common and narrowest region in our MM cell lines bearing 1q12-q22 amplification. Further, because the chromosomal gain around 1q21 has been reported to be a potential indicator for malignant progression and/or resistance to chemotherapy,17–19 we focused on one gene of those candidates, PDZK1, which are likely to be related to drug-resistant phenotype of tumors, as a probable target for HLG. Indeed, PDZK1 was involved in copy number gain at 1q12-q22 and consequently overexpressed in MM cell lines (Figure 3C). In primary cases of MM, this gene was frequently amplified (Figure 3D), even though we might underestimate their copy number ratios because of the contamination of normal cells in primary samples available for the present analysis. Those findings further support the hypothesis that PDZK1 was the positional and functional target of HLG at 1q12-q22 region.

PDZK1 encodes one of the PDZ domain-containing proteins that were reported to be involved in organizing proteins at the cell membrane38 and in linking transmembrane proteins to the actin cytoskeleton.39 Through these interactions, PDZ domain-containing proteins regulate a diverse set of cell functions, including signal transduction, cell polarity, cell differentiation, and ion transport.40,41 PDZK1 was first isolated in a yeast two-hybrid screen designed to identify proteins interacting with MAP17, a membrane-associated protein involved in regulation of cell proliferation.42 Subsequently, the interaction of PDZK1 with cMOAT, which is a canalicular organic anion transporter and known as the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) was identified.43 These findings suggested that the protein cluster formed by the association of PDZK1, cMOAT, and MAP17 may play an important role in the cellular mechanisms associated with multidrug resistance. cMOAT participates in the detoxification process by transporting organic anions through the cytoplasmic membrane, and prevents the accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs, such as cDDP, resulting in resistance to such agents. Overexpression of cMOAT has been observed in cell lines that had developed resistance to drug, and down-regulation of cMOAT expression by an anti-sense cDNA sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells to a number of chemotherapeutic drugs.44 Although overexpression of PDZK1 was reported in a variety of carcinomas,37 the clinicopathological and biological significance of overexpressed PDZK1 in tumorigenesis remains unknown.

In this study, we first reported that copy number gain/overexpression of PDZK1 might be related to the sensitivity of cell lines to various chemotherapeutic/cytotoxic reagents, and the introduction of a specific ASO for PDZK1 sensitizes MM cell lines to those reagents. Those findings suggest that PDZK1 is one of potential targets for chromosomal gain of 1q12-q22 region and associated with drug resistance of MM. In addition, it is possible that this gene might be an appropriate candidate for the target of novel therapeutic protocols. To understand the biological and clinicopathological significance of overexpression of this gene, further experiments using larger sets of primary samples and/or cell lines for the expression and functional characterization will be needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Masao Seto (Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute) for valuable comments, Professor Yusuke Nakamura (Human Genome Center, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo) for his continuous encouragement during the course of our progression in this work, and Ai Watanabe and Yuri Yoshinaga for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Johji Inazawa, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Molecular Cytogenetics, Medical Research Institute, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, 1-5-45 Yushima, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8510, Japan. E-mail: johinaz.cgen@mri.tmd.ac.jp.

Supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) and Scientific Research on Priority Areas (C) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology; Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology; Japan Science and Technology Corporation; and the Center of Excellence program for Frontier Research on Molecular Destruction and Reconstitution of Tooth and Bone.

References

- Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppa AM, Sotto JJ, Fuzibet JG, Rossi JF, Casassus P, Maisonneuve H, Facon T, Ifrah N, Payen C, Bataille R. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. Intergroupe Francais du Myelome. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:91–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek DF, Ahmann GJ, Greipp PR, Jalal SM, Westendorf JJ, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, Lust JA. Coexistence of aneuploid subclones within a myeloma cell line that exhibits clonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangement: clinical implications. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5320–5327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankathil R, Madhavan J, Gangadharan VP, Pillai GR, Nair MK. Nonrandom karyotype abnormalities in 36 multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;83:71–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(94)00186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer JR, Waldron JA, Jagannath S, Barlogie B. Cytogenetic findings in 200 patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;82:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(94)00284-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandecki M, Lai JL, Facon T. Multiple myeloma: almost all patients are cytogenetically abnormal. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:217–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-2939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrinakis NG, Gorgoulis VG, Foukas PG, Dimopoulos MA, Kittas C. Molecular aspects of multiple myeloma. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1217–1228. doi: 10.1023/a:1008331714186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM. Chromosome translocations in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2001;20:5611–5622. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calasanz MJ, Cigudosa JC, Odero MD, Ferreira C, Ardanaz MT, Fraile A, Carrasco JL, Sole F, Cuesta B, Gullon A. Cytogenetic analysis of 280 patients with multiple myeloma and related disorders: primary breakpoints and clinical correlations. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 1997;18:84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell TJ, Korsmeyer SJ. Progression from lymphoid hyperplasia to high-grade malignant lymphoma in mice transgenic for the t(14;18). Nature. 1991;349:254–256. doi: 10.1038/349254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callanan M, Leroux D, Magaud JP, Rimokh R. Implication of cyclin D1 in malignant lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol. 1996;7:191–203. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v7.i3-4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Baccon P, Leroux D, Dascalescu C, Duley S, Marais D, Esmenjaud E, Sotto JJ, Callanan M. Novel evidence of a role for chromosome 1 pericentric heterochromatin in the pathogenesis of B-cell lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2001;32:250–264. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoyama T, Nanjungud G, Chen W, Dyomin VG, Teruya-Feldstein J, Jhanwar SC, Zelenetz AD, Chaganti RS. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of genomic instability at the 1q12-22 chromosomal site in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2002;35:318–328. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avet-Loiseau H, Andree-Ashley LE, Moore DII, Mellerin MP, Feusner J, Bataille R, Pallavicini MG. Molecular cytogenetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma and plasma cell leukemia measured using comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 1997;19:124–133. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199706)19:2<124::aid-gcc8>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigudosa JC, Rao PH, Calasanz MJ, Odero MD, Michaeli J, Jhanwar SC, Chaganti RS. Characterization of nonrandom chromosomal gains and losses in multiple myeloma by comparative genomic hybridization. Blood. 1997;91:3007–3010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez NC, Hernandez JM, Garcia JL, Canizo MC, Gonzalez M, Hernandez J, Gonzalez MB, Garcia-Marcos MA, San Miguel JF. Differences in genetic changes between multiple myeloma and plasma cell leukemia demonstrated by comparative genomic hybridization. Leukemia. 2001;15:840–845. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer JR, Tricot G, Mattox S, Jagannath S, Barlogie B. Jumping translocations of chromosome 1q in multiple myeloma: evidence for a mechanism involving decondensation of pericentromeric heterochromatin. Blood. 1998;91:1732–1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S, Aninat-Meyer M, Schluns K, Gellert K, Dietel M, Petersen I. Chromosomal alterations in the clonal evolution to the metastatic stage of squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:65–73. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkkanen M, Elomaa I, Blomqvist C, Kivioja AH, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P, Bohling T, Valle J, Knuutila S. DNA sequence copy number increase at 8q: a potential new prognostic marker in high-grade osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:114–121. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990420)84:2<114::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh K, Takano M, Koshikawa T, Hirai M, Yoshida S, Mano Y, Yamamoto K, Ishii K, Kita T, Kikuchi Y, Nagata I, Miwa M, Uchida K. Gains of 1q21–q22 and 13q12–q14 are potential indicators for resistance to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2526–2531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis TG, Zalcberg IR, Coignet LJ, Wlodarska I, Stul M, Jadayel DM, Bastard C, Treleaven JG, Catovsky D, Silva ML, Dyer MJ. Molecular cloning of translocation t(1;14)(q21;q32) defines a novel gene (BCL9) at chromosome 1q21. Blood. 1998;91:1873–1881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig RW, Jabs EW, Zhou P, Kozopas KM, Hawkins AL, Rochelle JM, Seldin MF, Griffin CA. Human and mouse chromosomal mapping of the myeloid cell leukemia-1 gene: MCL1 maps to human chromosome 1q21, a region that is frequently altered in preneoplastic and neoplastic disease. Genomics. 1994;23:457–463. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon-Nguyen F, Della-Valle V, Mauchauffe M, Busson-Le Coniat M, Ghysdael J, Berger R, Bernard OA. The t(1;12)(q21;p13) translocation of human acute myeloblastic leukemia results in a TEL-ARNT fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6757–6762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120162297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse W, Zhu W, Chen HS, Cohen A. A novel gene, AF1q, fused to MLL in t(1;11) (q21;q23), is specifically expressed in leukemic and immature hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1995;85:650–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama S, Osawa M, Omine M, Ishikawa F. JTB: a novel membrane protein gene at 1q21 rearranged in a jumping translocation. Oncogene. 1999;18:2085–2090. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyomin VG, Palanisamy N, Lloyd KO, Dyomina K, Jhanwar SC, Houldsworth J, Chaganti RS. MUC1 is activated in a B-cell lymphoma by the t(1;14)(q21;q32) translocation and is rearranged and amplified in B-cell lymphoma subsets. Blood. 2000;95:2666–2671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles F, Goy A, Remache Y, Shue P, Zelenetz AD. MUC1 dysregulation as the consequence of a t(1;14)(q21;q32) translocation in an extranodal lymphoma. Blood. 2000;95:2930–2936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Palanisamy N, Schmidt H, Teruya-Feldstein J, Jhanwar SC, Zelenetz AD, Houldsworth J, Chaganti RS. Deregulation of FCGR2B expression by 1q21 rearrangements in follicular lymphomas. Oncogene. 2001;20:7686–7693. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callanan MB, Le Baccon P, Mossuz P, Duley S, Bastard C, Hamoudi R, Dyer MJ, Klobeck G, Rimokh R, Sotto JJ, Leroux D. The IgG Fc receptor, FcgammaRIIB, is a target for deregulation by chromosomal translocation in malignant lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:309–314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzivassiliou G, Miller I, Takizawa J, Palanisamy N, Rao PH, Iida S, Tagawa S, Taniwaki M, Russo J, Neri A, Cattoretti G, Clynes R, Mendelsohn C, Chaganti RS, Dalla-Favera R. IRTA1 and IRTA2, novel immunoglobulin superfamily receptors expressed in B cells and involved in chromosome 1q21 abnormalities in B cell malignancy. Immunity. 2001;14:277–289. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privitera E, Kamps MP, Hayashi Y, Inaba T, Shapiro LH, Raimondi SC, Behm F, Hendershot L, Carroll AJ, Baltimore D. Different molecular consequences of the 1;19 chromosomal translocation in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1992;79:1781–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi A, Kallioniemi OP, Sudar D, Rutovitz D, Gray JW, Waldman F, Pinkel D. Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumors. Science. 1992;258:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1359641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda Y, Kurihara N, Imoto I, Yasui K, Yoshida M, Yanagihara K, Park J-G, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J. CD44 is a potential target of amplification within the 11p13 amplicon detected in gastric cancer cell lines. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2000;29:315–324. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::aid-gcc1047>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyama Y, Sakabe T, Shinomiya T, Mori T, Fukuda Y, Inazawa J. Identification of amplified DNA sequences on double minute chromosomes in a leukemic cell line KY821 by means of spectral karyotyping and comparative genomic hybridization. J Hum Genet. 1998;43:187–190. doi: 10.1007/s100380050067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito-Ohara F, Imoto I, Inoue J, Hosoi H, Nakagawara A, Sugimoto T, Inazawa J. PPM1D is a potential target for 17q gain in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1876–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Imoto I, Katahira T, Hirasawa A, Ishiwata I, Emi M, Takayama M, Sato A, Inazawa J. Differentially regulated genes as putative targets of amplifications at 20q in ovarian cancers. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:1114–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John DV, Guilhem C, Karin T, Michel J, Guilhem R, Marie-Claude D, Jean-François R, Nadir M, Bernard K. Identifying intercellular signaling genes expressed in malignant plasma cells by using complementary DNA arrays. Blood. 2001;98:771–780. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher O, Comella N, Gilchrist A, Pal R, Tognazzi K, Brown LF, Knoll JH. PDZK1, a novel PDZ domain-containing protein up-regulated in carcinomas and mapped to chromosome 1q21, interacts with cMOAT (MRP2), the multidrug resistance-associated protein. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1161–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Higuchi O, Mizuno K. Cytoplasmic localization of LIM-kinase 1 is directed by a short sequence within the PDZ domain. Exp Cell Res. 1998;241:242–252. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandai K, Nakanishi H, Satoh A, Obaishi H, Wada M, Nishioka H, Itoh M, Mizoguchi A, Aoki T, Fujimoto T, Matsuda Y, Tsukita S, Takai Y. Afadin: a novel actin filament-binding protein with one PDZ domain localized at cadherin-based cell-to-cell adherens junction. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:517–528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomi P, Macalma T, Beckerle MC. Purification and characterization of an actinin-binding PDZ-LIM protein that is up-regulated during muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29242–29250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Niethammer M, Rothschild A, Jan YN, Sheng M. Clustering of Shaker-type K+ channels by interaction with a family of membrane-associated guanylate kinases. Nature. 1995;378:85–88. doi: 10.1038/378085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher O, Comella N, Tognazzi K, Brown LF. Identification and partial characterization of PDZK1: a novel protein containing PDZ interaction domains. Lab Invest. 1998;78:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool M, de Haas M, Scheffer GL, Scheper RJ, van Eijk MJ, Juijn JA, Baas F, Borst P. Analysis of expression of cMOAT (MRP2), MRP3, MRP4, and MRP5, homologues of the multidrug resistance-associated protein gene (MRP1), in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3537–3547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Wada M, Kohno K, Nakamura T, Kawabe T, Kawakami M, Kagotani K, Okumura K, Akiyama S, Kuwano M. A human canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter (cMOAT) gene is overexpressed in cisplatin-resistant human cancer cell lines with decreased drug accumulation. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4124–4129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]