Abstract

In transgenic mice expressing human mutant β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and mutant presenilin-1 (PS1), Aβ antibodies labeled granules, about 1 μm in diameter, in the perikaryon of neurons clustered in the isocortex, hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, and brainstem. The granules were present before the onset of Aβ deposits; their number increased up to 9 months and decreased in 15-month-old animals. They were immunostained by antibodies against Aβ 40, Aβ 42, and APP C-terminal region. In double immunofluorescence experiments, the intracellular Aβ co-localized with lysosome markers and less frequently with MG160, a Golgi marker. Aβ accumulation correlated with an increased volume of lysosomes and Golgi apparatus, while the volume of endoplasmic reticulum and early endosomes did not change. Some granules were immunolabeled with an antibody against flotillin-1, a raft marker. At electron microscopy, Aβ, APP-C terminal, cathepsin D, and flotillin-1 epitopes were found in the lumen of multivesicular bodies. This study shows that Aβ peptide and APP C-terminal region accumulate in multivesicular bodies containing lysosomal enzymes, while APP N-terminus is excluded from them. Multivesicular bodies could secondarily liberate their content in the extracellular space as suggested by the association of cathepsin D with Aβ peptide in the extracellular space.

One of the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the extracellular deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides.1,2 The Aβ peptide originates from the proteolytic processing of single-pass transmembrane proteins, the β-amyloid precursor proteins (APP).3,4 The Aβ peptide ends at amino acid 40 or 42 and may be N-truncated.5,6 Aβ peptide may be produced from APP in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER),7,8 in post-ER compartments9,10 or in the trans-Golgi network11,12 and targeted to secretion vesicles, the so-called “secretory pathway.”

Alternatively, APP can be internalized from the cell surface through the endocytic pathway and directed toward the endosomal-lysosomal system.13–15 Impeding endocytosis decreases Aβ production.16 Abnormal early endosomes are detected in sporadic Alzheimer disease, Down syndrome, and in cellular models of Niemann-Pick type C in which Aβ peptide accumulates intracellularly.17–20 Overexpression of cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor, a molecule involved in the transport of hydrolases toward the endosomal-lysosomal system, dramatically increases the secretion of Aβ 40 and Aβ 42 in the culture medium.21 In the same way, Rab5-stimulated up-regulation of the endocytic pathway increases intracellular APP β-cleavage and Aβ peptide production.22 Where the γ-cleavage occurs in the endosomal-lysosomal pathway, remains controversial: it could take place in lipid rafts,23 located at the cellular membrane,24 where Aβ starts to accumulate25 or in the lysosome itself, which contains the necessary enzymatic machinery.26

Accumulation of Aβ peptide within neurons has been documented in AD,27,28 particularly in trisomy-21.29,30 The intracellular accumulation was maximal at early stages of the disease and decreased thereafter. It occurs in multivesicular bodies, within presynaptic and especially postsynaptic compartments, in APP transgenic mice and in AD.31 The multivesicular body (MVB) belongs to the late endosome compartment and fuses with lysosomes. The lumen of this ovoid or spherical organelle contains membrane-bound vesicles. MVB is a highly conserved compartment that helps regulating and degrading transmembrane proteins. These proteins initially located in the membrane of the endosome are secondarily targeted to the endoluminal vesicles (for review, reference 32). Accumulation of APP has been shown in MVB–like organelles in cultured leptomeningeal smooth muscle cells and brain pericytes.33

Aβ peptide also accumulates in the neuronal cell body of APPxPS1 transgenic mice, when they are young, and disappears in aged animals.34–36 We studied the time course of Aβ intracellular accumulation and characterized the intracellular compartments containing Aβ-immunoreactive material using double immunofluorescence and electron microscopy. We investigated brain samples from transgenic mice expressing human-mutated APP (APP751 with both the Swedish and the London mutation) and human PS1 bearing the M146L mutation.36 Double immunofluorescent labeling with a combination of antibodies against Aβ, APP, and different organelle markers were examined with confocal microscopy and the volume occupied by the various organelles was evaluated. The intracellular localization of the Aβ peptide was determined at the ultrastructural level by immunogold electron microscopy.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Mice and Tissue Preparation

Generation and characterization of single APP751 with the Swedish and London mutation (APP751SL) and double APP751SLxPS1M146L transgenic mice were described previously.34–37 In these animals, APP is expressed at a high level in all cortical neurons under the control of the Thy-1 promoter. Human PS1 with the M146L mutation is expressed under the control of the HMG-CoA reductase promoter. The level of amyloid load was found to be quite reproducible at a given age; the coefficient of error between animals is below 10%.36 PS1 single transgenic mice, which do not develop amyloid plaques, and wild-type animals were also examined.

Intracytoplasmic Aβ accumulation was searched for in 24 APPxPS1 mice, five APP single transgenic, 13 PS1 single transgenic mice, and six wild-type animals of the same genetic background (C57Bl6) (Table 1). Animals were handled by Transgenic Services Department Charles River Laboratories France, and handled according to the French guidelines for animal care.

Table 1.

Genotype, Age, and Number of Animals

| Genotype Age (months) | WT | PS1 | APP | APPxPS1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | |||

| 3 | 2 | 4 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | 2 | 4 | ||

| 7 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 9 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 11 | 1 | |||

| 12 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| 15 | 1 | |||

| Total | 6 | 13 | 5 | 24 |

Brain Tissue Preparation for Morphological Analysis

Animals (4 wild-type mice, 13 PS1, 4 APP, and 22 APPxPS1 transgenic mice from 2 to 15 months of age, Table 1) were sacrificed by intracardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate- buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Brains were removed and post-fixed for 1 hour in PFA at 4°C. Coronal sections (2-mm thick) were made, sectioned with a freezing microtome or embedded in paraffin. For electron microscopy, three additional 9-month-old animals (one APP, one APPxPS1, and one wild-type) were used. Post-fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 24 hours was added to the previous protocol.

Brain Tissue Preparation for Western Blot Analysis

For Western blot analysis, crude brain homogenates were used. Snap-frozen cerebral hemispheres from one wild-type and one APPxPS1 (9- month-old animals) were weighed and homogenized on ice in 10 volumes (w/v) of buffer containing 0.32 mol/L sucrose, 4 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 and a protein inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins from crude brain homogenates (10 μg) were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer, then separated by electrophoresis on 12% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (0.45 μm, Amersham, France), blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in TBST (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20), and incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody. The following primary antibodies were applied to the membrane (Table 2): anti-APP Nter 1:2000, anti-APP Cter (737–751) 1:1000, anti-APP Cter (705–751) 1:3000, and anti-Aβ8–17 1:500 in 5% milk TBST. Binding of the primary antibody was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at a 1:5000 dilution followed by the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL, Amersham, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Table 2.

Antibodies

| Antibody | Dilution | Immunogen | Source | Labeling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP-Cter rabbit polyclonal | 1/2000 | Synthetic peptide conjugated to KLH corresponding to aa 705–751 of the huAPP751 | B. Allinquant, INSERM U573, Paris, France | C-terminal region of APP |

| APP-Cter goat polyclonal | 1/100 | Synthetic peptide conjugated to BSA, corresponding to aa 737–751 of the huAPP751 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK #2083 | C-terminal region of APP |

| APP Nter mouse monoclonal (clone 22C11) | 1/200 | purified recombinant Alzheimer precursor APP695 fusion protein | Chemicon International, distributed by Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France | N-terminal region of APP (aa 66–81) |

| β-amyloid (Aβ) mouse monoclonal (clone 6F/D3) | 1/200 | KLH-aa 8–17 from human Aβ peptide | Dako Corporation, Glostrup, Denmark | Aβ peptide 40 & 42 |

| β-amyloid (Aβ) rabbit polyclonal | 1/100 | Synthetic β-amyloid peptide 1–40 conjugated to BSA | Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA | Aβ peptide 40 & 42 |

| β-amyloid (Aβ) E50 Rabbit polyclonal | 1/100 | Aa 17–31 human Aβ peptide | H. Akiyama, Institute of Psychiatry, Tokyo, Japan | Aβ peptide 40 & 42 |

| β-amyloid (Aβ) FCA 18 rabbit polyclonal | 1/500 | KLH-aa 1–8 from human Aβ peptide KLH-DAEFRHDS-Cys | F. Checler Sofia Antipolis, Nice, France | N terminal part of Aβ |

| β-amyloid (Aβ) FCA 3340 rabbit polyclonal | 1/50 | Aa 33–40 human Aβ peptide KLH-Cys-GLMVGGVV | F. Checler Sofia Antipolis, Nice, France | Aβ 40 |

| β-amyloid (Aβ) FCA 3542 rabbit polyclonal | 1/50 | Aa 35–42 human Aβ peptide KLH-Cys-MVGGVVIA | F. Checler Sofia Antipolis, Nice, France | Aβ 42 |

| Bip (Grp78) rabbit polyclonal | 1/200 | KLH-aa 645–654 rat Grp78 | StressGen Biotechnologies Corporation, Victoria | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Golgi rabbit polyclonal | 1/1000 | MG-160 sialoglycoprotein | N. Gonatas, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA | Golgi apparatus |

| Cathepsin D rabbit polyclonal | 1/1000 | Human liver active cathepsin D | Dako Corporation, Glostrup, Denmark | Enriched in lysosome lumen |

| LAMP2 rabbit polyclonal | 1/200 | aa 1–207 of human Lamp2 | Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA | Lysosome membrane |

| Early endosomal antigen 1 rabbit polyclonal | 1/250 | human EEA1 aa 1391–1410 | Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, USA | Early endosomes |

| Cox 2 rabbit polyclonal | 1/500 | subunit 2 of human mitochondrial complex IV | A. Lombès, Inserm U153, Paris | Mitochondria |

| Flotillin-1 mouse monoclonal | 1/1000 | aa 312–428 (C-terminal) of mouse flotillin-1 | Translab, Erembodegem, Belgium | Protein enriched in raft |

| GFAP rabbit polyclonal | 1/500 | GFAP from cow spinal cord | Dako Corporation, Glostrup, Denmark | Astrocytes |

| Ubiquitin rabbit polyclonal | 1/500 | Ubiquitin isolated from cow erythrocytes | Dako Corporation, Glostrup, Denmark | Ubiquitinated proteins |

| SNAP25 mouse monoclonal, (clone SMI 81) | 1/5000 | synaptosome-associated protein | Sternberger, Lutherville, USA | Synapses |

Histology

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Bodian silver stains were routinely performed. To demonstrate the amyloid nature of the deposits, sections were stained with Congo red and thioflavin S.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed on 5-μm thick paraffin sections. Sections were de-paraffinized in xylene, re-hydrated through ethanol (100%, 90%, 80%, and 70%) and finally brought to water. They were microwaved twice at 400 W in citrate buffer 0.01 mol/L, pH 6.0 for 10 minutes. When immunoperoxidase was used, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched in a TBST solution containing 0.3% H2O2 and 20% methanol. Non-specific binding was blocked by incubating sections for 20 minutes in 2% bovine serum albumin in TBST. Appropriate dilutions of primary antibodies (Table 2) were then applied overnight in a humidified chamber at room temperature.

Monoclonal antibody 22C11 against APP (APP66–81) is commercially available. It does not cross-react with the Aβ sequence.38,39 Rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal region of APP (generous gift of B. Allinquant, Inserm U573, Centre Paul Broca, Paris, France) was generated in the rabbit using the intracellular portion corresponding to amino acids (aa) 705–751. This APP fragment does not include the Aβ peptide sequence. Another polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal APP region encompassing aa 737–751 made in the goat was purchased (Abcam). This antibody does not recognize the Aβ sequence. E50 (generous gift of H. Akiyama, Institute of Psychiatry, Tokyo, Japan) is a polyclonal antibody raised against aa 17–31 (Aβ17–31) of human Aβ peptide. FCA 1–8 (generous gift of F. Checler, Institut de Pharmcologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Valbonne Sophia-Antipolis, France) recognizes the N-terminal portion of Aβ (aa 1–8), while, FCA40 and FCA42 (generous gifts of F. Checler) are specific for Aβ C terminus (including the COOH group), ending respectively at aa 40 and 42.40 The antibodies against organelles included a rabbit anti-serum against MG160 (a Golgi sialoglycoprotein), which labels Golgi cis- and medial cis-ternae41 (generous gift of N. Gonatas, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and a rabbit anti-serum against Cox2, a mitochondrial enzyme (generous gift of A. Lombès, Inserm U573, Paris, France).42 The GRP78 antibody recognizes a KDEL sequence causing retention in the ER. The antibody against cathepsin D labels the lysosomes in which it is concentrated. EEA1 (early endosome antigen 1), a 162-kd autoantigen associated with subacute cutaneous systemic lupus erythematosus, localizes to early endosomes through the zinc-binding motif FYVE and interacts with Rab-5.43 (Table 2).

Immunoperoxidase

The appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody was applied for 30 minutes followed by 30 minutes incubation with streptavidine-peroxidase complex. The horseradish peroxidase activity was revealed with 3–3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). The ABC-system and the peroxidase substrate were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Chemmate K500111, Dako Corporation, Glostrup). Primary antibodies were omitted in control sections.

Immunofluorescence

Double immunofluorescence, on sections from 5- and 9-month-old animals, made use of antibodies from different species (one mouse monoclonal and one rabbit polyclonal). The secondary antibodies were directly linked with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), carbocyanin 2 or 3 (Cy2 or Cy3). In some experiments, an intermediate step of streptavidin-biotin amplification was applied (Table 3). Slides were examined with a Leica confocal microscope (TCS), equipped with a krypton-argon laser (excitation wavelengths at 488, 568, and 647 nm).

Table 3.

Secondary Antibodies and Fluorochromes for Immunofluorescence

| Fluorochrome | Specificity | Species | Absorption (nm) | Emission (nm) | Dilution | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cy3 | Anti-rabbit | Goat | 552 | 570 | 1/400 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories |

| Cy2 | Streptavidin conjugated (used with biotinylated anti-mouse) | 492 | 510 | Streptavidin CY2:1/400 (biotinylated anti-mouse:1/200) | Streptavidin CY2, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; Biotinylated anti-mouse, Amersham | |

| FITC | Anti-rabbit | Goat | 492 | 520 | 1/400 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories |

| Cy3 | Anti-mouse | Goat | 552 | 570 | 1/400 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories |

Mapping of Aβ-Positive Granules and Plaques

To visualize the distribution of Aβ-positive intraneuronal granules and amyloid deposits, a series of sagittal section cut at 25-μm thickness was obtained at ages 2, 5, 9, 11, and 15 months. They were immunostained with anti-Aβ8–17. The maps were drawn with the following apparatus, furnished by Explora Nova (La Rochelle, France) a camera, plugged in the phototube of a microscope, transmitted the microscopical image to a video screen. Linear transducers, fastened to the microscope moving stage, recorded its position and transmitted it to a PC computer. The borders of the sample and of the regions of interest were manually drawn. The profiles of the Aβ-positive deposits and of the granules containing neuronal profiles were pointed, using a mouse, on the video screen. The software (Mercator, Explora Nova, La Rochelle, France) drew the map at the appropriate scale on the video screen and kept track of the pointed profiles. A label indicated, on the video screen, the profiles, which had already been pointed to avoid counting them twice.

Quantitative Evaluation

Quantitative evaluation of Aβ co-localization with organelle markers (Grp78 for endoplasmic reticulum, MG160 for Golgi apparatus, cathepsin D for lysosomes and EEA1 for early endosomes) was performed on pictures of cortical neurons obtained with a confocal microscope using a X100 immersion oil objective. Neuronal profiles containing both Aβ-positive granules and the organelle marker were selected. For each neuronal profile, three images were analyzed. The green and red channels were acquired separately to avoid cross-talk: Aβ immunofluorescence was recorded on one channel; immunofluorescence of the organelle marker was collected on the other one. Merging these two images using a binary AND operation provided a third picture reflecting Aβ peptide co-localization with the organelle marker. The measures were performed using Image J, an image analysis program for PC, available on the Internet. (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). We assessed, after adequate thresholding, the total area of Aβ immunoreactivity within the neuron, the area occupied by the organelle and finally the area occupied by the co-localization of Aβ peptide with the organelle marker. The ratio: (area of Aβ immunoreactivity colocalized with an organelle marker)/(total area occupied by Aβ immunoreactivity) was used to estimate the volume proportion of total intracellular Aβ peptide localised in this organelle. According to Delesse principle44, this ratio is AA = Av (AA = proportion of surface area; Vv = proportion of volume). For each organelle, a mean of 17 neurons could be evaluated in this way. The surface area occupied by Aβ peptide was variable from one neuron to the next. Using this variability, we tried to find out which organelle had increased its volume when the neuron had increased its content in Aβ peptide. Such a parallel increase can, indeed, be detected by a high correlation coefficient between the area of Aβ immunoreactivity and the area occupied by the organelle marker under investigation.

Immunogold Electron Microscopy

One-mm3 blocks were excised from area corresponding to deep cortical layers and post-fixed in glutaraldehyde. Semi-thin sections, 1-μm thick, were obtained with a Reichert-Jung ultramicrotome. They were stained with toluidine blue (1%) for 2 minutes. Neurons located in plaque rich areas were selected and 90-nm thick sections were obtained. Immunogold labeling was performed according to standard post-embedding protocol.45 Anti-Aβ17–31, anti-C-terminal APP, anti-flotillin and anti-cathepsin D were applied in simple immunolabeling experiments. Ten-nm and 20-nm gold particles, coupled with species-specific secondary antibody, were used for double labeling experiments. The sections were incubated with the following couples of primary antibodies: APP Cter705–751 & flotillin-1, Aβ8–17 & cathepsin-D, Aβ17–31 & flotillin-1. The sections were observed with a CM100 (Philips, Limeil-Brévannes, France) electron microscope.

Results

Aβ Deposits

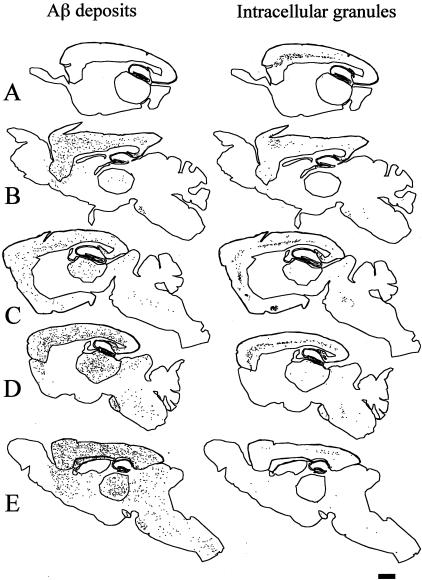

All of the antibodies against Aβ peptide revealed extracellular deposits in APPxPS1 transgenic animals.36 Aβ deposits were not seen at 2 months of age (Figure 1A, left). At 5 months, they were numerous in the isocortex and in the hippocampus; some were found in the thalamus; none were present in the brainstem (Figure 1B, left). At 9 months, deposits were also found in the brainstem and their density kept increasing in the isocortex, hippocampus, and thalamus (Figure 1C, left). The deposits were dense and spherical. Ill-limited, diffuse deposits, such as those observed in human aging, were never observed. The deposits affected all of the layers but were predominantly located in deep layer V and VI of the isocortex (Figure 2A). In the hippocampus, Aβ deposits mainly involved the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, the pyramidal layer and stratum oriens of the CA1-CA3 sectors (Figure 2, A and B). The core of Aβ deposits were Congo red- and thioflavin S-positive. Occasional capillaries were labeled. Deposits in the striatum or in the cerebellum were not observed.

Figure 1.

Maps of the extracellular Aβ deposits and Aβ-positive granules. The extracellular deposits of Aβ peptide (left) and the neurons containing Aβ-positive granules (right) were manually mapped using a dedicated software (Explora Nova, La Rochelle). Each dot is an Aβ deposit (left) or a granule containing neurone (right) A: 2 months; B: 5 months; C: 9 months; D: 11 months; E: 15 months. Bar, 1 mm.

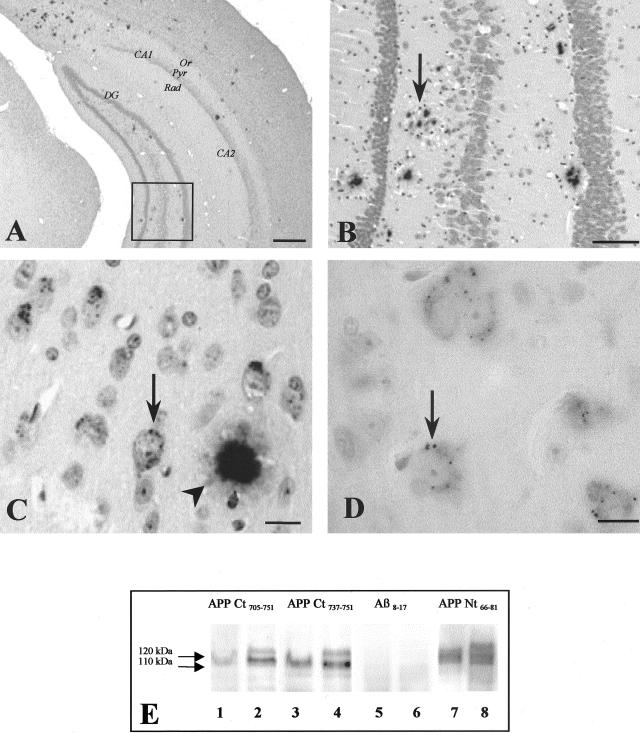

Figure 2.

Immunoperoxidase Aβ8–17 immunostaining of Thy-1 double APP751SLxPS1M146L transgenic mouse (A, B, and C) and Thy-1 APP751SL single transgenic (D) mouse brain sections. The mice were 9 months (A, B, and C) and 5 months old (D). A: Distribution of Aβ immunoreactive deposits. Or, stratum oriens; Pyr, stratum pyramidale; Rad, stratum radiatum. The rectangle in A is enlarged in B. B: Dentate gyrus corresponding to rectangle in A, numerous plaques are visible (the arrow points to one of them). C: Intraneuronal granules (arrow) close to a plaque (arrowhead) in APPxPS1 transgenic animal. D: Intraneuronal granules (arrow) in an APP single transgenic animal. Bars: A, 0,5 mm; B, 50 μm; C, 15 μm; D, 10 μm. E: Brain homogenates from one wild-type mouse (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) and one Thy-1 double APP751SLxPS1M146L transgenic mouse (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) were analyzed by immunoblot using antibodies against APP Cter 705–751 (lanes 1 and 2), APP Cter 737–751 (lanes 3 and 4), Aβ8–17 (lanes 5 and 6), and APP Nter66–81 (lanes 7 and 8). Two bands (approximate molecular weight, 120 and 110 kd band, arrows) were detected by the antibodies to APP Cter and the antibody to APP Nter (22C11). These bands correspond to the full-length APP. The 120 kd visible in the transgenic animal corresponds to the human APP transgene. The antibody against Aβ8–17 did not cross-react with the full-length APP, either native or transgenic (lanes 5 and 6).

Aβ-Positive Intracellular Granules

Aβ antibodies revealed spherical granules (0.5 to 1 μm in diameter), in APPxPS1 transgenic animals (Figure 2, C and D). The granules were immunolabeled by Aβ antibodies, covering the whole length of the peptide including its C- and N-termini (Table 2). They were Congo red- and thioflavin S-negative, were not autofluorescent when examined under UV light, and were not ubiquitinated.

The granules were located in the perinuclear region of the cell body and were identical in young and old animals (Figure 2, A and B). The cells containing the granules were identified as neuronal by their shape and by the presence of SNAP 25-positive synapses along their cell membrane. GFAp-positive cells, endothelial cells or pericytes never contained granules. The neurons containing Aβ-positive granules were found in isocortical layers III, V and VI, CA1-CA3 sectors of the hippocampus, subiculum, amygdaloid complex, dorsal thalamus, and brainstem. No granule containing neurons were ever observed in the striatum or in the cerebellum. Granules containing neurons were seen in the isocortex of an animal as young as 2 months of age and devoid of any extracellular deposits (Figure 1A, right). They were also seen in the hippocampus and brainstem at 5 months and, at 9 months, in the thalamus (Figure 1, B and C, right).

To determine whether the granules were related to the PS1 transgene, we also searched for granules in APP and in PS1 single transgenic mice. They were present in APP (Figure 2D), but not in PS1, single transgenic mice. They were not detected in wild-type animals.

Presence of APP C-Terminal Fragments in the Granules

The antibodies against the C-terminal region of APP (rabbit polyclonal against APP705–751 and goat polyclonal against APP737–751) as well as the monoclonal antibody 22C11 (APP66–81) against the N-terminal region of APP labeled a band at 110 kd on blots of brain extracts of wild-type mice. In transgenic animals an additional band was detected at 120 kd, at the expected weight for the product of the huAPP751 transgene (Figure 2E). The 110- and 120-kd bands were not recognized by the Aβ8–17 antibody.

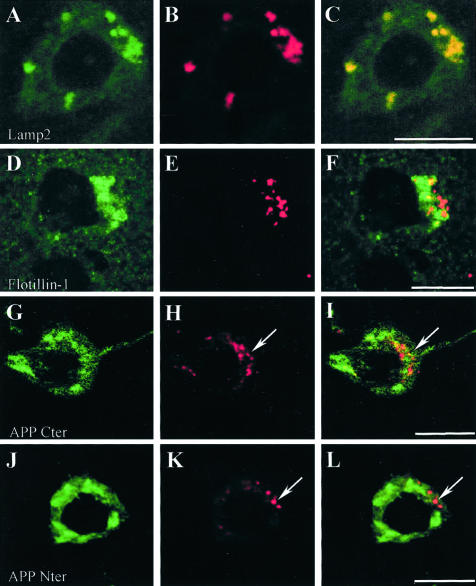

Immunohistochemistry showed that the C-terminal antibodies, anti- APP Cter 705–751 and anti-APP Cter 737–751, did not label Aβ peptide deposits but immunostained some dystrophic neurites which were not recognized by the Aβ antibodies. The antibodies against APP Cter 705–751 and APP Cter 737–751 labeled a high proportion (88 ± 7%, mean ± SEM) of Aβ-positive granules in double immunostained sections (Figure 3G). A small proportion of granules were only labeled by the APP Cter antibodies, a few were only labeled by the Aβ antibodies (Figure 3, G to I). By contrast, the monoclonal antibody 22C11 (APP66–81), directed against the N-terminal part of the molecule, did not label any granule (Figure 3, J to L).

Figure 3.

Double immunofluorescence examined with laser confocal microscope. Labeling with the Aβ peptide antibody is shown in red. Labeling with the other antibodies is shown in green. See Table 2 for details concerning the antibodies. Lamp2: lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2. Flotillin-1: a marker of raft and of multivesicular bodies. APP Cter, C terminus of the amyloid precursor protein (antibody raised against APP705–751); APP Nter, N terminus of the amyloid precursor protein (antibody raised against APP66–81). In H and I, arrows point to intraneuronal granules that are immunolabeled with both anti-Aβ8–17 and APP Cter (APP705–751) antibodies. In K and L, arrows point to intraneuronal granules, which are only labeled with anti-Aβ antibody (Aβ1–40 polyclonal, Chemicon) and not with the APP Nter antibody. Bars: A to F, 5 μm; G to L, 10 μm.

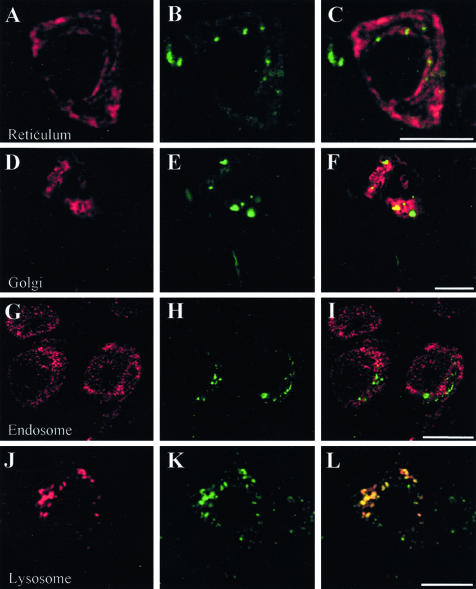

Double Labeling of the Granules with Organelle Markers

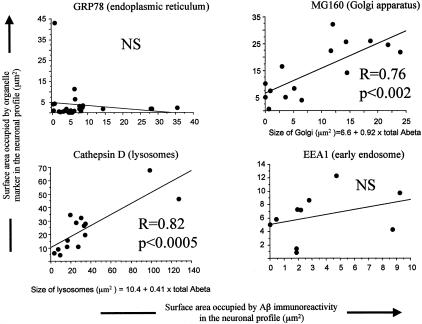

In double immunofluorescence experiments using antibodies directed against Aβ peptide and organelle markers, Aβ immunoreactive material co-localized mainly with lamp-2 (Figure 3A), a lysosomal membrane protein, cathepsin D (Figure 4J), a hydrolase usually found in lysosomes, and MG160, a marker of the Golgi apparatus (Figure 4D). There was no difference in co-localization at 5 and 9 months. Co-localization between Aβ peptide and organelle markers involved 14%, 42%, 57%, and 8% of the total intracellular Aβ, for GRP78 (endoplasmic reticulum), MG160 (Golgi apparatus), cathepsin D (lysosomes), and EEA1 (early endosomes), respectively (Table 4). The sum of the percentages of co-localization (121%) was higher than 100% because the measure could only be done on neurons where both Aβ and organelle markers immunoreactivity was present. Co-localization was, therefore, over-represented in this sample. Correlation between the area occupied by Aβ immunoreactivity in the neuron and the size of the organelles (corresponding to the area of immunoreactivity of their markers) was highly significant for lysosomes (correlation between immunoreactive areas occupied by Aβ peptide and cathepsin D: r = 0.82; P < 0.0005) and for Golgi apparatus (MG160): r = 0.76; P < 0.002. They were not significant for endoplasmic reticulum (r = 0.125; P = 0.54) and early endosomes (r = −0.152; P = 0.67) (Figure 5). This result indicates that the volume of the lysosomes and of the Golgi apparatus was increased in neurons with an increased content of Aβ peptide, while the volume of the endoplasmic reticulum and of the early endosomes did not change. Intracellular Aβ peptide occupied a larger volume in the neurons where a co-localization with cathepsin D was observed than when a co-localization with EEA1 or GRP78 was present (analysis of variance, PLSD P < 0.01 in both cases).

Figure 4.

Double immunofluorescence examined with laser confocal microscope. Antibodies labeling organelles markers (A, D, G, and J) and Aβ8–17 (B, E, H, and K) are visualized respectively in red and in green. See Table 2 for details concerning the antibodies. The pictures on the right (C, F, I, and L) are merged images of the green and red signals; yellow indicates co-localization. Reticulum, endoplasmic reticulum labeled by Bip/GRP78; Golgi, Golgi apparatus labeled by MG160; Endosome, labeling by the antibody directed against EEA1 (early endosome autoantigen I). Lysosomes, organelles labeled by an antibody against cathepsin D, ie, lysosomes and multivesicular bodies having merged with lysosomes. Bars: A to C, 5 μm; D to L, 10 μm.

Table 4.

Co-localization of Organelle Markers and Aβ

| Amyloid protein antibody | Organelle marker antibodies | Cellular compartment | Aβ co-localized/total Aβ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ8–17 mAb (6FD3) | Grp78 | Endoplasmic reticulum | 14 |

| MG160 | Golgi | 42 | |

| Cathepsin D | Lysosomes | 57 | |

| EEA1 | Early endosomes | 8 | |

| SNAP25 | Synaptic vesicles | 0 | |

| Cox2 | Mitochondria | 0 |

Figure 5.

Proportion (%) of the total volume of intracellular Aβ peptide co-localized with the organelle marker. The Aβ antibody is the monoclonal antibody 6FD3, directed against amino acids 8–17 of the peptide (Dako). See Table 2 for details concerning the antibodies.

Antibodies directed against cathepsin D (Figure 4J), MG 160 (Figure 4D) and GRP78 (Figure 4A) labeled their respective compartment and some Aβ-positive granules. In contrast, the antibody against EEA1 revealed small vesicles, which were, for most of them, devoid of Aβ labeling (Figure 4G) and did not show the granules. Flotillin-1 antibody labeled only some Aβ-positive granules (Figure 4, D to F). SNAP 25 (a synaptic marker) and Cox2 (a marker of mitochondria) did not co-localize with Aβ peptide (not shown).

Immunoelectron Microscopy

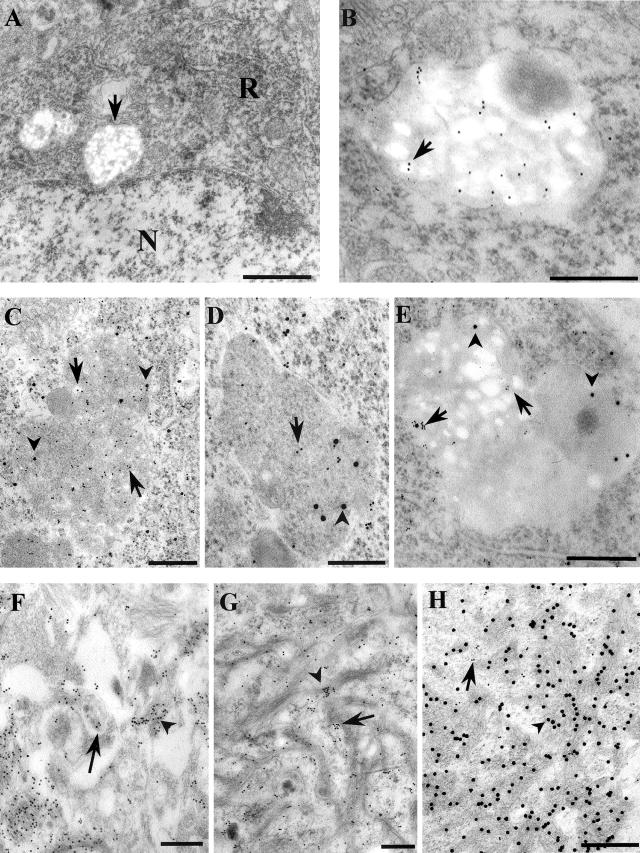

At the ultrastructural level, antibodies against Aβ8–17 or Aβ17–3146 decorated both intracellular structures and extracellular deposits (Figure 6, B, F and H). A few gold particles were found in the neuronal ER, in the Golgi apparatus, in pre- and post-synaptic structures. Many gold particles decorated intraneuronal multivesicular bodies (MVB). These MVB were ovoid (∼500 to 1000 nm small axis, ∼700 to 1500 nm long axis) or round structures (∼700 to 1000 nm in diameter), limited by a single unit membrane and containing between 10 and 30 intralumenal vesicles and a few dense bodies (Figure 6, A and B). Some vesicles appeared electrolucent, probably because liposoluble material had been extracted through the processing of the sample (Figure 6, A, B, and E). Some other MVB had a dark matrix reminiscent of the lysosomal content (= dark MVB) (Figure 6, C, D, and E). No MVB contained amyloid fibrils. The Aβ containing MVB were most often located in the perinuclear region (Figure 6A). Double immunoelectron microscopy using two-sized gold particles (10 and 20 nm) showed the co-occurrence of Aβ and flotillin, of Aβ and cathepsin D, of flotillin and APPcter, (Figure 6, C to E) in dark multivesicular bodies.

Figure 6.

Electron microscopy. A: Conventional electron microscopy picture showing the appearance of intracellular granule (arrow); N, nucleus; R, endoplasmic reticulum. B to H: Immunoelectron microscopy. B: Labeling of an intraneuronal granule with anti-Aβ17–31 (E50,46). Gold particles are located in the lumenal vesicles (arrow). C: Double immunolabeling of intraneuronal granule with anti-Aβ17–31 (20-nm gold particle, arrowhead) and anti-flotillin (10-nm gold particle, arrow). D: Double immunolabeling of intraneuronal granule with anti-Aβ8–17 (10-nm gold particle, arrow) and anti-cathepsin D (20-nm gold particle, arrowhead). E: Double immunolabeling of a multivesicular body–lysosome with anti-APP Cter (20-nm gold particle, arrowhead) and anti-flotillin (10-nm gold particle, arrow). F: Labeling of an Aβ deposit with the anti-Aβ17–31 antibody decorating amyloid fibrils (arrowhead). The content of an extracellular vesicle is also labeled (arrow). (G) Labeling of Aβ deposit with the anti-cathepsin D antibody showing gold particles associated with amyloid fibrils (arrowhead) or between them (arrow). H: Double immunolabeling of an Aβ deposit with anti-Aβ17–31 (20-nm gold particle, arrowhead) and anti-flotillin (10-nm gold particle, arrow). Note that 10-nm gold particles are located in between the typical amyloid fibrils. Bars A to C and E to H, 400 nm; D, 250 nm.

Aβ-positive extracellular deposits appeared as bundles of 10 nm fibrils, located close to cell processes containing numerous dense bodies or lamellar structures which remained unlabeled. Small vesicles (20 to 60 nm in diameter), containing Aβ17–31, were found admixed with amyloid fibrils within the deposits (Figure 6F). Cathepsin D immunoreactivity (Figure 6G) was observed on or between amyloid fibrils.

Discussion

We have shown that intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ peptide took place in granules visible at light microscopy in Thy-1 APPxPS1 transgenic mice. These granules were detected in the isocortex and hippocampus at 2 months of age, at a stage where Aβ extracellular deposits were not yet present. Their number increased between 2 and 11 months of age (between 2 and 9 months in the hippocampus and brainstem) and decreased thereafter, confirming previous data.34,36,47 Aβ-positive granules has also been detected in single APP transgenic mice.36

In contrast to granules, the number of extracellular Aβ deposits progressed even in aged animals. All of the regions where neurons harbored granules (isocortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and brainstem) contained Aβ deposits from 5 months on. It should be stressed here that the distribution of plaques in these Thy-1 APPxPS1 transgenic mice differs from what is observed in human (thalamic plaques being rare in man). Conversely, neurons were devoid of granules in the regions which did not contain extracellular Aβ deposits (eg, cerebellum and striatum).

At electron miscroscopy, Aβ immunoreactivity was concentrated in MVB whose external diameter corresponded to the mean diameter of granules seen at light microscopy. The lumenal vesicles (20 to 40 nm in diameter) are below the resolving power of the light microscope. Some of these MVB were dark. Their matrix appeared to have the same aspect as the lysosomal matrix, suggesting that fusion with lysosome(s) had occurred.

The Aβ-positive granules reacted with Aβ1–8, Aβ8–17, Aβ33–40, and Aβ35–42 antibodies. The labeling of the granules by antibody Aβ1–8 and Aβ8–17 indicates that the reactive epitope was not a product of the α-cleavage, which involves aa 16 and 17. The labeling by Aβ33–40 and Aβ35–42 antibodies shows that the reactive sequence was not embedded in APP, since these antibodies recognize an epitope that includes the terminal COOH group.40 On the other hand, the labeling of the granules by the two C-terminal APP antibodies cannot be interpreted as a cross-reaction with Aβ peptide since these antibodies were raised against peptides that did not include the Aβ sequence. Finally, the absence of labeling of the granules by the APP66–81 (22C11 monoclonal) demonstrates that the N-terminus of the protein is excluded from the granules. One may conclude that the granules do not contain full-length APP.

Full-length Aβ peptide and APP C-terminus were close enough to appear co-localized at confocal microscopy (ie, at a distance <250 nm48,49). Immunoelectron microscopy confirmed the presence of the C-terminal epitopes of APP in the granules. Only the APP cleaved by the β-secretase (βAPP Cter) appeared to be targeted to the granules. The presence of β-cleaved C-terminal fragments in vesicular compartments was also mentioned in cells overexpressing Rab5.22 It raises the possibility that γ-secretase cleaves βAPP-Cter within the granules themselves, in agreement with recent findings indicating that PS1 and nicastrin, two constituents of the γ-secretase complex,50 are localized in the membrane of the lysosome.26

Using double immunofluorescence with confocal microscopy, we found that most of the granules were labeled by antibodies directed against constituents of the lysosomes (cathepsin D or LAMP2). Aβ epitopes were sometimes co-localized with MG160 (a marker of Golgi apparatus) and rarely with Grp78/Bip (a marker of the ER). Co-localization of Aβ peptide and cathepsin D was significantly associated with an increased volume of cathepsin D immunoreactivity, suggesting that Aβ peptide produced in excess accumulated in lysosomes or in MVB containing lysosomal enzymes. Of notice in this regard is the presence of LAMPs in the membrane of MVB in cells where it has been studied such as the human neutrophils.51 Although not as marked, there was also an increase in the volume of the Golgi apparatus while both the ER and early endosomes were of normal size. The normal size of the endosomes raises questions. In sporadic Alzheimer disease, trisomy 21, and in the segmental trisomy 16 mouse model, the volume of the early endosomes is increased,18,52,53 but it has been found normal in human cases of PS1 mutation and in another line of APPxPS1 double transgenic mice,53 a normal morphology being obviously still compatible with an increased turnover of APP. As previously shown,53 overexpression of APP is not sufficient alone to increase the volume of the endosomal compartment and some other factor(s) (located on the chromosome 16 in the trisomy 16 mouse model) seem(s) also necessary. Alternatively, the PS1 mutation (as in our mice or in the human disease53) could affect the cellular topography of Aβ production, so preventing the enlargement of the endosomes.

The finding that flotillin-1 antibody (a raft marker54) labeled some of the granules and that, ultrastructurally, there was co-occurrence of flotillin, Aβ, and APP Cter in small aggregates found in the MVB, may be of importance in view of the literature indicating that a significant fraction of APP is concentrated in rafts55,56 and that raft proteins are concentrated in the vesicles of MVB and exosomes.57 Multivesicular bodies are involved in recycling and degradation of membrane proteins. In several cell types, such as the intestinal cells,58 the dendritic cells59 or B-lymphocytes,60 the content of MVB are extruded as “exosomes.” With immunoelectron microscopy using an anti-Aβ antibody, we showed the presence of gold particles in multivesicular bodies in transgenic mice. Direct evidence of a γ-secretase activity or of the presence of its constituents in multivesicular bodies is still lacking in the nervous system but PS1 has been identified in azurophil granules of polymorphonuclear cells and in α-granules of platelets.61 Both organelles are considered to be specialized MVB.32

The lumenal vesicles of the MVB are known to be enriched in lipids, including cholesterol.62 This lipid environment could explain why Aβ peptide, whose amino acid sequence is, for a third of its length, hydrophobic, does not aggregate in the hydrophilic cytoplasmic environment.

Our observations provide additional support to previous findings showing that Aβ accumulates in neurons.7,8,11,12,34,36,47,63 In the present model there is no evidence that intracellular Aβ is rapidly toxic to the neuron: at 2 months, when only granules are present, there is no sign of inflammation, neuritic dystrophy or neuronal loss. The granules could however play a role in the long run, impeding normal cellular function and causing neuronal death.37

The origin of the extracellular Aβ has not been fully elucidated. Could it originate from the multivesicular body where it accumulates? In man, as in transgenic mice, the abundance of Aβ-positive granules decreases in the later stages of the disease, while the peptide accumulates in the extracellular space. Moreover, in the transgenic mice, extracellular Aβ deposits and intraneuronal granules occur in the same areas of the brain. These observations are compatible with the initial accumulation of Aβ within the neuron and its secondary secretion outside the cell. Extracellular Aβ was found co-localized with cathepsin D in these transgenic mice as in man.64,65 The presence of cathepsin D immunoreactivity and enzymatic activity in postmortem CSF of Alzheimer disease patient66 is also an evidence of its accumulation in the extracellular space. This could be explained by the exocytosis of the MVB-lysosomal content, including both Aβ peptide and cathepsin D. Lysosomes with a secretory activity (so-called “secretory lysosomes”) have been described in other systems.67 They share characteristics of, or are identical with, MVB. Since extracellular Aβ is co-localized with cathepsin D65, a lysosomal marker, we raise the possibility that Aβ peptide is stored in secretory lysosomes, known, in other cell types, to liberate their content outside the cell.

Acknowledgments

We thank Haruhiko Akiyama, Nicolas Gonatas, Anne Lombès, and Frédéric Checler for the generous gift of their excellent antibodies. We also thank Denis Lecren for his help in the preparation of the illustrations.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Charles Duyckaerts, Laboratoire de Neuropathologie Raymond Escourolle, Groupe hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière, 47, boulevard de l’Hôpital, 75013 Paris, France. E-mail: charles.duyckaerts@psl.asp-hop-paris.fr.

Supported by Alzheimer Network/Aventis-Pharma.

N.G. is recipient of a grant from Association France Alzheimer.

References

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Xu H, Jovanovic JN, Buxbaum JD, Wang R, Greengard P, Relkin NR, Gandy S. Generation and regulation of beta-amyloid peptide variants by neurons. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1920–1925. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43). Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DG, Forman MS, Sung JC, Leight S, Kolson DL, Iwatsubo T, Lee VM, Doms RW. Alzheimer’s A beta(1–42) is generated in the endoplasmic reticulum/intermediate compartment of NT2N cells. Nat Med. 1997;3:1021–1023. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann T, Bieger SC, Bruhl B, Tienari PJ, Ida N, Allsop D, Roberts GW, Masters CL, Dotti CG, Unsicker K, Beyreuther K. Distinct sites of intracellular production for Alzheimer’s disease A beta40/42 amyloid peptides. Nat Med. 1997;3:1016–1020. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltese WA, Wilson S, Tan Y, Suomensaari S, Sinha S, Barbour R, McConlogue L. Retention of the Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor fragment C99 in the endoplasmic reticulum prevents formation of amyloid beta-peptide. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20267–20279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata H, Tomita T, Maruyama K, Iwatsubo T. Subcellular compartment and molecular subdomain of beta-amyloid precursor protein relevant to the Abeta 42-promoting effects of Alzheimer mutant presenilin 2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21678–21685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Sweeney D, Wang R, Thinakaran G, Lo AC, Sisodia SS, Greengard P, Gandy S. Generation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid protein in the trans-Golgi network in the apparent absence of vesicle formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3748–3752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Cole GM, Chu T, Xia W, Galasko D, Yamaguchi H, Tanemura K, Frautschy SA, Takashima A. Intracellular Abeta is increased by okadaic acid exposure in transfected neuronal and non-neuronal cell lines. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T, Koo EH, Selkoe DJ. Trafficking of cell-surface amyloid beta-protein precursor: II. endocytosis, recycling, and lysosomal targeting detected by immunolocalization. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:999–1008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo EH, Squazzo SL, Selkoe DJ, Koo CH. Trafficking of cell-surface amyloid beta-protein precursor: I. secretion, endocytosis and recycling as detected by labeled monoclonal antibody. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:991–998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Koo EH, Mellon A, Hung AY, Selkoe DJ. Targeting of cell-surface beta-amyloid precursor protein to lysosomes: alternative processing into amyloid-bearing fragments. Nature. 1992;357:500–503. doi: 10.1038/357500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez RG, Soriano S, Hayes JD, Ostaszewski B, Xia W, Selkoe DJ, Chen X, Stokin GB, Koo EH. Mutagenesis identifies new signals for beta-amyloid precursor protein endocytosis, turnover, and the generation of secreted fragments, including Abeta42. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18851–18856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Barnett JL, Pieroni C, Nixon RA. Increased neuronal endocytosis and protease delivery to early endosomes in sporadic Alzheimer‘s disease: neuropathologic evidence for a mechanism of increased β-amyloidogenesis. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6142–6151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06142.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Peterhoff CM, Troncoso JC, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman BT, Nixon RA. Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid beta deposition in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA. Niemann-Pick type C disease and Alzheimer’s disease: the APP-endosome connection fattens up. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:757–761. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63163-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin LW, Maezawa I, Vincent I, Bird T. Intracellular accumulation of amyloidogenic fragments of amyloid-beta precursor protein in neurons with Niemann-Pick type C defects is associated with endosomal abnormalities. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:975–985. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews PM, Guerra CB, Jiang Y, Grbovic OM, Kao BH, Schmidt SD, Dinakar R, Mercken M, Hille-Rehfeld A, Rohrer J, Mehta P, Cataldo A-M, Nixon RA. Alzheimer’s disease-related overexpression of the cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor Increases Abeta secretion: role for altered lysosomal hydrolase distribution in beta-amyloidogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5299–5307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grbovic OM, Mathews PM, Jiang Y, Schmidt SD, Dinakar R, Summers-Terio NB, Ceresa BP, Nixon RA, Cataldo AM. Rab5-stimulated up-regulation of the endocytic pathway increases intracellular beta-cleaved amyloid precursor protein carboxyl-terminal fragment levels and Abeta production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31261–31268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayashi T, Shoji M, Younkin LH, Wen-Lang L, Dickson DW, Murakami T, Matsubara E, Abe K, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Dimeric amyloid beta protein rapidly accumulates in lipid rafts followed by apolipoprotein E and phosphorylated tau accumulation in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3801–3809. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5543-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torp R, Ottersen OP, Cotman CW, Head E. Identification of neuronal plasma membrane microdomains that colocalize beta-amyloid and presenilin: implications for beta-amyloid precursor protein processing. Neuroscience. 2003;120:291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Maat-Schieman ML, van Duinen SG, Prins FA, Neeskens P, Natte R, Roos RA. Amyloid beta protein (Abeta) starts to deposit as plasma membrane-bound form in diffuse plaques of brains from hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type, Alzheimer disease, and nondemented aged subjects. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:723–732. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.8.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak SH, Bagshaw RD, Guiral M, Zhang S, Ackerley CA, Pak BJ, Callahan JW, Mahuran DJ. Presenilin-1, nicastrin, amyloid precursor protein, and gamma-secretase activity are co-localized in the lysosomal membrane. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26687–26694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m304009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui DH, Dobo E, Makifuchi T, Akiyama H, Kawakatsu S, Petit A, Checler F, Araki W, Takahashi K, Tabira T. Apoptotic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease frequently show intracellular Abeta42 labeling. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001;3:231–239. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Tsai J, Naslund J, Vincent B, Edgar M, Checler F, Greenfield JP, Haroutunian V, Buxbaum JD, Xu H, Greengard P, Relkin NR. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in human brain. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyure KA, Durham R, Stewart WF, Smialek JE, Troncoso JC. Intraneuronal abeta-amyloid precedes development of amyloid plaques in Down syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:489–492. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0489-IAAPDO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori C, Spooner ET, Wisniewski KE, Wisniewski TM, Yamaguchi H, Saido TC, Tolan DR, Selkoe DJ, Lemere CA. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in Down syndrome brain. Amyloid. 2002;9:88–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi RH, Milner TA, Li F, Nam EE, Edgar MA, Yamaguchi H, Beal MF, Xu H, Greengard P, Gouras GK. Intraneuronal Alzheimer abeta42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann DJ, Odorizzi G, Emr SD. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:893–905. doi: 10.1038/nrm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek MM, Otte-Holler I, Fransen JA, de Waal RM. Accumulation of the amyloid-beta precursor protein in multivesicular body-like organelles. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:681–690. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirths O, Multhaup G, Czech C, Feldmann N, Blanchard V, Tremp G, Beyreuther K, Pradier L, Bayer TA. Intraneuronal APP/A beta trafficking and plaque formation in beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 transgenic mice. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:275–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech C, Delaere P, Macq AF, Reibaud M, Dreisler S, Touchet N, Schombert B, Mazadier M, Mercken L, Theisen M, Pradier L, Octave JN, Beyreuther K, Tremp G. Proteolytical processing of mutated human amyloid precursor protein in transgenic mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;47:108–116. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard V, Moussaoui S, Czech C, Touchet N, Bonici B, Planche M, Canton T, Jedidi I, Gohin M, Wirths O, Bayer TA, Langui D, Duyckaerts C, Tremp G, Pradier L. Time sequence of maturation of dystrophic neurites associated with Abeta deposits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:247–263. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz C, Rutten BP, Pielen A, Schafer S, Wirths O, Tremp G, Czech C, Blanchard V, Multhaup G, Rezaie P, Korr H, Steinbusch HW, Pradier L, Bayer TA. Hippocampal neuron loss exceeds amyloid plaque load in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63235-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J, Twiesselmann C, Kummer MP, Romagnoli P, Herzog V. A possible role for the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein in the regulation of epidermal basal cell proliferation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:905–914. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbich C, Monning U, Grund C, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid-like properties of peptides flanking the epitope of amyloid precursor protein-specific monoclonal antibody 22C11. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26571–26577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barelli H, Lebeau A, Vizzavona J, Delaere P, Chevallier N, Drouot C, Marambaud P, Ancolio K, Buxbaum JD, Khorkova O, Heroux J, Sahasrabudhe S, Martinez J, Warter JM, Mohr M, Checler F. Characterization of new polyclonal antibodies specific for 40 and 42 amino acid-long amyloid beta peptides: their use to examine the cell biology of presenilins and the immunohistochemistry of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy cases. Mol Med. 1997;3:695–707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croul S, Mezitis SG, Stieber A, Chen YJ, Gonatas JO, Goud B, Gonatas NK. Immunocytochemical visualization of the Golgi apparatus in several species, including human, and tissues with an antiserum against MG-160, a sialoglycoprotein of rat Golgi apparatus. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:957–963. doi: 10.1177/38.7.2355176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possekel S, Lombes A, Ogier de Baulny H, Cheval MA, Fardeau M, Kadenbach B, Romero NB. Immunohistochemical analysis of muscle cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in children. Histochem Cell Biol. 1995;103:59–68. doi: 10.1007/BF01464476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H, Aasland R, Toh BH, D’Arrigo A. Endosomal localization of the autoantigen EEA1 is mediated by a zinc-binding FYVE finger. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24048–24054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER. Stereological methods. London: Academic Press; Practical Methods for Biological Morphometry. 1979:pp 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- El Hachimi KH, Verga L, Giaccone G, Tagliavini F, Frangione B, Bugiani O, Foncin JF. Relationship between non-fibrillary amyloid precursors and cell processes in the cortical neuropil of Alzheimer patients. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90734-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Kondo H, Mori H, Kametani F, Nishimura T, Ikeda K, Kato M, McGeer PL. The amino-terminally truncated forms of amyloid beta-protein in brain macrophages in the ischemic lesions of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurosci Lett. 1996;219:115–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirths O, Multhaup G, Czech C, Blanchard V, Moussaoui S, Tremp G, Pradier L, Beyreuther K, Bayer TA. Intraneuronal Abeta accumulation precedes plaque formation in beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 double-transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett. 2001;306:116–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heun P, Laroche T, Raghuraman MK, Gasser SM. The positioning and dynamics of origins of replication in the budding yeast nucleus. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:385–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PD, Harper IS, Swedlow JR. To 5D and beyond: quantitative fluorescence microscopy in the postgenomic era. Traffic. 2002;3:29–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasugi N, Tomita T, Hayashi I, Tsuruoka M, Niimura M, Takahashi Y, Thinakaran G, Iwatsubo T. The role of presenilin cofactors in the gamma-secretase complex. Nature. 2003;422:438–441. doi: 10.1038/nature01506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainton DF. Distinct granule populations in human neutrophils and lysosomal organelles identified by immuno-electron microscopy. J Immunol Methods. 1999;232:153–168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo A, Rebeck GW, Ghetri B, Hulette C, Lippa C, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn C, Cras P, Bogdanovic N, Bird T, Peterhoff C, Nixon R. Endocytic disturbances distinguish among subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:661–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Petanceska S, Peterhoff CM, Terio NB, Epstein CJ, Villar A, Carlson EJ, Staufenbiel M, Nixon RA. App gene dosage modulates endosomal abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease in a segmental trisomy 16 mouse model of Down syndrome. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6788–6792. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06788.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel P, Scherer P, Schnitzer J, Phil O, Lisanti M, Lodish H. Flotillin and epidermal surface antigen define a new family of caveolae-associated integral membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13793–13802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillot C, Prochiantz A, Rougon G, Allinquant B. Axonal amyloid precursor protein expressed by neurons in vitro is present in a membrane fraction with caveolae-like properties. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7640–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin ET, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. Amyloid precursor protein, although partially detergent-insoluble in mouse cerebral cortex, behaves as an atypical lipid raft protein. Biochem J. 1999;344:23–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gassart A, Geminard C, Fevrier B, Raposo G, Vidal M. Lipid raft-associated proteins are sorted in exosomes. Blood. 2003;102:4336–4344. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Niel G, Raposo G, Candalh C, Boussac M, Hershberg R, Cerf-Bensussan N, Heyman M. Intestinal epithelial cells secrete exosome-like vesicles. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:337–349. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery C, Regnault A, Garin J, Wolfers J, Zitvogel L, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Amigorena S. Molecular characterization of dendritic cell-derived exosomes: selective accumulation of the heat shock protein hsc73. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:599–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Nijman HW, Stoorvogel W, Liejendekker R, Harding CV, Melief CJ, Geuze HJ. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1161–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirinics ZK, Calafat J, Udby L, Lovelock J, Kjeldsen L, Rothermund K, Sisodia SS, Borregaard N, Corey SJ. Identification of the presenilins in hematopoietic cells with localization of presenilin 1 to neutrophil and platelet granules. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;28:28–38. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobius W, Van Donselaar E, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Shimada Y, Heijnen HF, Slot JW, Geuze HJ. Recycling compartments and the internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies harbor most of the cholesterol found in the endocytic pathway. Traffic. 2003;4:222–231. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield JP, Tsai J, Gouras GK, Hai B, Thinakaran G, Checler F, Sisodia SS, Greengard P, Xu H. Endoplasmic reticulum and trans-Golgi network generate distinct populations of Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:742–747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Nixon RA. Enzymatically active lysosomal proteases are associated with amyloid deposits in Alzheimer brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3861–3865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Thayer CY, Bird ED, Wheelock TR, Nixon RA. Lysosomal proteinase antigens are prominently localized within senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a neuronal origin. Brain Res. 1990;513:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90456-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwagerl AL, Mohan PS, Cataldo AM, Vonsattel JP, Kowall NW, Nixon RA. Elevated levels of the endosomal-lysosomal proteinase cathepsin D in cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer disease. J Neurochem. 1995;64:443–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blott EJ, Griffiths GM. Secretory lysosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:122–131. doi: 10.1038/nrm732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]