Abstract

The tertiary interactions between amide-I vibrators on the separate helices of transmembrane helix dimers were probed by ultrafast 2D vibrational photon echo spectroscopy. The 2D IR approach proves to be a useful structural method for the study of membrane-bound structures. The 27-residue human erythrocyte protein Glycophorin A transmembrane peptide sequence: KKITLIIFG79VMAGVIGTILLISWG94IKK was labeled at G79 and G94 with 13C 16O or 13C

16O or 13C 18O. The isotopomers and their 50:50 mixtures formed helical dimers in SDS micelles whose 2D IR spectra showed components from homodimers when both helices had either 13C

18O. The isotopomers and their 50:50 mixtures formed helical dimers in SDS micelles whose 2D IR spectra showed components from homodimers when both helices had either 13C 16O or 13C

16O or 13C 18O substitution and a heterodimer when one had 13C

18O substitution and a heterodimer when one had 13C 16O substitution and the other had 13C

16O substitution and the other had 13C 18O substitution. The cross-peaks in the pure heterodimer 2D IR difference spectrum and the splitting of the homodimer peaks in the linear IR spectrum show that the amide-I mode is delocalized across a pair of helices. The excitation exchange coupling in the range 4.3–6.3 cm−1 arises from through-space interactions between amide units on different helices. The angle between the two Gly79 amide-I transition dipoles, estimated at 103° from linear IR spectroscopy and 110° from 2D IR spectroscopy, combined with the coupling led to a structural picture of the hydrophobic interface that is remarkably consistent with results from NMR on helix dimers. The helix crossing angle in SDS is estimated at 45°. Two-dimensional IR spectroscopy also sets limits on the range of geometrical parameters for the helix dimers from an analysis of the coupling constant distribution.

18O substitution. The cross-peaks in the pure heterodimer 2D IR difference spectrum and the splitting of the homodimer peaks in the linear IR spectrum show that the amide-I mode is delocalized across a pair of helices. The excitation exchange coupling in the range 4.3–6.3 cm−1 arises from through-space interactions between amide units on different helices. The angle between the two Gly79 amide-I transition dipoles, estimated at 103° from linear IR spectroscopy and 110° from 2D IR spectroscopy, combined with the coupling led to a structural picture of the hydrophobic interface that is remarkably consistent with results from NMR on helix dimers. The helix crossing angle in SDS is estimated at 45°. Two-dimensional IR spectroscopy also sets limits on the range of geometrical parameters for the helix dimers from an analysis of the coupling constant distribution.

Keywords: tertiary interaction, vibrational spectra, multidimensional spectroscopy

Two-dimensional IR spectroscopy (1–6) is a promising new method with which to probe structures and their motions in complex systems. Recent applications of this method to biologically related molecules have yielded novel structural and dynamical results not readily obtainable by other methods for small peptides (7, 8), soluble helices (9, 10), membrane-bound helices (11), lipids (12), β-sheets (13, 14), and model secondary structures (15, 16). The 2D IR approach is one that can be immediately applicable to a wide variety of sample types ranging from solutions to solids, including aqueous and lipid environments. The method exposes interactions between spatially nearby vibrational modes by converting three pulse photon echo signals into 2D spectral maps in the IR, analogous to 2D NMR spectra.

The amide-I vibrational bands of polypeptides are highly degenerate because, for each residue, their frequencies are approximately the same and the interactions among them are not strong enough to separately display them as individual, assignable transitions. The combination of multiple isotope selection and 2D IR spectroscopy that spreads the transitions into two dimensions proves to be a useful strategy that can simplify and expose the underlying transitions of the diffuse amide bands and allow their features to be characterized at a residue level. For example the 2D IR spectrum of a water-soluble helix selectively substituted with 13C 16O and 13C

16O and 13C 18O provided characteristics of pairs of coupled residues and the visualization of the sequence dependence of the structural dynamics (17).

18O provided characteristics of pairs of coupled residues and the visualization of the sequence dependence of the structural dynamics (17).

This paper introduces a comparable approach to investigate tertiary interactions between vibrational modes in Glycophorin A (GpA), a transmembrane (TM) dimer of interacting helices (Fig. 1). The GpA TM helix provides an excellent prototype for the study of TM helix association, a key event in the folding of membrane proteins (18). The dimer also is an appropriate model for these investigations, because it is stable in a variety of micelles, including SDS (19), and a solution NMR structure is available (20). There are two Gly residues at the dimer interface that allow an intimate contact of the main chain, a feature frequently observed in TM helical interfaces (21, 22). Because vibrational coupling is sensitive to distance, the proximity of the backbones is advantageous. GpA also was selected because verification of the applicability of the 2D IR method to membrane protein aggregates is of great interest and because there is a chronic paucity of structural information for this class of proteins. The angular information that is obtainable with the present method can be used to help derive molecular models. This information is especially useful because the simple topology generally adopted by membrane proteins (bundles of roughly parallel α-helices) is such that computational procedures can be effectively assisted by a relatively small number of spatial constraints (23–28), particularly when a regular helix conformation can be assumed, which is likely to be the case for oligomeric complexes of single helices such as GpA.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the GpA TM dimer (20). The backbones of the two helical segments are yellow and green. The carbonyl atoms of the interfacial Gly79 positions and the control Gly94 position are represented as spheres.

The Labeling Notation

Four peptides were prepared in the study of the GpA dimer interface by linear and 2D IR spectroscopy. The unlabeled peptide, denoted as G79, had a deuterium label at the α-carbon of Gly79, which we presumed has no measurable effect on the amide-I transitions. The 13C 16O-labeled peptides were denoted as either G*79 or G*94, and the 13C

16O-labeled peptides were denoted as either G*79 or G*94, and the 13C 18O-labeled peptide was denoted as G**79. The samples of pure G*79 and G**79 yield in the micelle either 13C

18O-labeled peptide was denoted as G**79. The samples of pure G*79 and G**79 yield in the micelle either 13C 16O or 13C

16O or 13C 18O homodimers, denoted as G*79/G*79 and G**79/G**79, respectively. A 50:50 mixture of G*79 and G**79, denoted as G*79 + G**79, yields one part of each of the homodimers in addition to one each of the heterodimers denoted as G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79. Peptide G*94, which has 13C

18O homodimers, denoted as G*79/G*79 and G**79/G**79, respectively. A 50:50 mixture of G*79 and G**79, denoted as G*79 + G**79, yields one part of each of the homodimers in addition to one each of the heterodimers denoted as G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79. Peptide G*94, which has 13C 16O at residue 94 was used to obtain G*94/G*94 and G*94 + G**79, with the latter yielding homodimers and heterodimers in the micelle. The mixture G79 + G**79 of unlabeled and 13C

16O at residue 94 was used to obtain G*94/G*94 and G*94 + G**79, with the latter yielding homodimers and heterodimers in the micelle. The mixture G79 + G**79 of unlabeled and 13C 18O-labeled GpA was used as a control. The typical GpA TM helix dimer structure (20) is illustrated in Fig. 1.

18O-labeled GpA was used as a control. The typical GpA TM helix dimer structure (20) is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results

Linear IR Spectroscopy.

The FTIR results are shown in Fig. 2 a and b with the isotopomer region expanded and each spectrum normalized to the optical density of the main TM helical band of G79. The main amide-I' bands are in the region 1,630–1,660 cm−1, and the band at 1,674 cm−1 is trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The low- frequency (1,630 cm−1) part of the main helix band is dominated by a secondary structure that is not imbedded in the micelle, with the shift to lower wave number arising from hydration of the amide groups (1, 29). Neglecting TFA, the amide-I' spectrum of G79 can be fitted to two broad transitions, one at ≈1,635 cm−1 that is associated with misfolded residues or those outside the micelle and another that is ≈2.3 times stronger at ≈1,655 cm−1 and corresponds to the structure in the micelle. The 13C 16O transition of G*79 appears at ≈1,613 cm−1. The 13C

16O transition of G*79 appears at ≈1,613 cm−1. The 13C 16O natural abundance transitions of G79 at ≈1,615 cm−1 have a much reduced intensity due to the large spread of transition frequencies and relaxation times that occur within the random residue distribution. The line shape of the G**79 isotopomer is noticeably asymmetric and broader than the other transitions, indicating that it corresponds to at least two underlying spectral components. It will be seen that this splitting is the result of an exciton interaction. This asymmetric 13C

16O natural abundance transitions of G79 at ≈1,615 cm−1 have a much reduced intensity due to the large spread of transition frequencies and relaxation times that occur within the random residue distribution. The line shape of the G**79 isotopomer is noticeably asymmetric and broader than the other transitions, indicating that it corresponds to at least two underlying spectral components. It will be seen that this splitting is the result of an exciton interaction. This asymmetric 13C 18O region of G**79 after the subtraction of G79 to remove the background was least-squares-fitted to two Gaussian bands at 1,589.5 ± 0.8 cm−1 and 1,598.1 ± 0.8 cm−1, which are separated by 8.6 ± 1.6 cm−1, as shown in Fig. 2c. Both of the widths of the two underlying bands are 14.0 ± 1.5 cm−1. The intensity ratio of the low-frequency to high-frequency component in G**79 is 1.6 ± 0.1. A comparable asymmetry is observed for the isotope region of G*79, but it is not as convincingly analyzed because of the underlying broad and symmetric 13C

18O region of G**79 after the subtraction of G79 to remove the background was least-squares-fitted to two Gaussian bands at 1,589.5 ± 0.8 cm−1 and 1,598.1 ± 0.8 cm−1, which are separated by 8.6 ± 1.6 cm−1, as shown in Fig. 2c. Both of the widths of the two underlying bands are 14.0 ± 1.5 cm−1. The intensity ratio of the low-frequency to high-frequency component in G**79 is 1.6 ± 0.1. A comparable asymmetry is observed for the isotope region of G*79, but it is not as convincingly analyzed because of the underlying broad and symmetric 13C 16O natural abundance contribution at about the same frequency. The absorption cross-section of 13C

16O natural abundance contribution at about the same frequency. The absorption cross-section of 13C 16O is ≈1.3 times larger than 13C

16O is ≈1.3 times larger than 13C 18O because the 13C

18O because the 13C 16O states are coupled more strongly to the neighboring 12C

16O states are coupled more strongly to the neighboring 12C 16O states.

16O states.

Fig. 2.

Linear IR and 2D IR spectra of GpA TM samples. (a) FTIR spectra (pathlength, 25 μm) of homodimers G79 (spectrum 1), G*79 (spectrum 2), and G**79 (spectrum 3) and heterodimers G*79 + G**79 (spectrum 4), G*94 + G**79 (spectrum 5), and G79 + G**79 (spectrum 6) in 5% SDS. (b) Magnification of the 13C 18O and 13C

18O and 13C 16O bands circled in a. (c) The fitting of the 13C

16O bands circled in a. (c) The fitting of the 13C 18O mode of G**79 in FTIR showing the two underlying components as dashed black lines and the sum as a dotted line. (d) The diagonal slices of the rephasing magnitude spectra (in Fig. 3) and the fitted components in G**79 (dark lines).

18O mode of G**79 in FTIR showing the two underlying components as dashed black lines and the sum as a dotted line. (d) The diagonal slices of the rephasing magnitude spectra (in Fig. 3) and the fitted components in G**79 (dark lines).

Two-Dimensional IR Spectroscopy.

The expectations for a mixed 13C 16O and 13C

16O and 13C 18O isotopomer are that the isotopically substituted amide transitions of a helix are split by the difference in the isotope shifts for the 13C

18O isotopomer are that the isotopically substituted amide transitions of a helix are split by the difference in the isotope shifts for the 13C 16O (≈38–43 cm−1) and 13C

16O (≈38–43 cm−1) and 13C 18O (≈62–67 cm−1) substitutions (17). The estimated (see below) zero-order frequency separation in the present case is ≈21 cm−1. If the selected modes are coupled, cross-peaks should appear in the 2D IR spectra. Each diagonal 2D IR band consists of two components having opposite signs corresponding to the v = 0→1 and v = 1→2 transition regions, the latter being shifted to lower frequency by the diagonal anharmonicity. Each cross-peak also will consist of two overlapping bands having opposite signs and separated by the mixed mode anharmonicity. The results can be interpreted in terms of a two-state quantum-mechanical description of the selected pair of amide modes when they are both significantly frequency-down-shifted from the dominant 12C

18O (≈62–67 cm−1) substitutions (17). The estimated (see below) zero-order frequency separation in the present case is ≈21 cm−1. If the selected modes are coupled, cross-peaks should appear in the 2D IR spectra. Each diagonal 2D IR band consists of two components having opposite signs corresponding to the v = 0→1 and v = 1→2 transition regions, the latter being shifted to lower frequency by the diagonal anharmonicity. Each cross-peak also will consist of two overlapping bands having opposite signs and separated by the mixed mode anharmonicity. The results can be interpreted in terms of a two-state quantum-mechanical description of the selected pair of amide modes when they are both significantly frequency-down-shifted from the dominant 12C 16O bands of the peptide.

16O bands of the peptide.

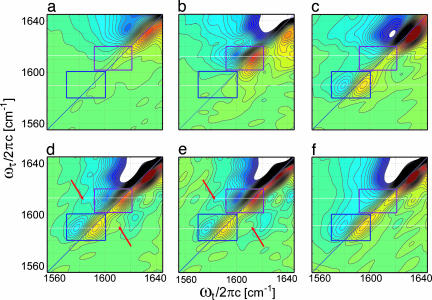

The cross-peaks also are seen in the absolute magnitudes of the 2D IR spectra for G**79 and G*79 + G**79 (Fig. 3 a and b). Fig. 2d shows traces of these spectra along the diagonals through the 13C 18O peak centers. In this representation, the spectrum is positive everywhere, whereas in the absorptive 2D IR spectrum, the interference alters the cross-peak shapes to make them less obvious. The control sample G*94 + G**79 (Fig. 3c) shows no cross-peaks. The 2D correlation spectra of various GpA samples are shown in Fig. 4. The echo signals are dominated by the elliptically shaped diagonal peaks corresponding to the v = 0→1 (red) and v = 1→2 (blue) transitions. The regions where the 13C

18O peak centers. In this representation, the spectrum is positive everywhere, whereas in the absorptive 2D IR spectrum, the interference alters the cross-peak shapes to make them less obvious. The control sample G*94 + G**79 (Fig. 3c) shows no cross-peaks. The 2D correlation spectra of various GpA samples are shown in Fig. 4. The echo signals are dominated by the elliptically shaped diagonal peaks corresponding to the v = 0→1 (red) and v = 1→2 (blue) transitions. The regions where the 13C 16O and 13C

16O and 13C 18O diagonal transitions are expected are highlighted as rectangles. The G79 sample (Fig. 4a) shows only a weak natural abundance peak, whereas G*79 and G**79 show the spectra of the homodimers G*79/G*79 (Fig. 4b) and G**79/G**79 (Fig. 4c). These spectra consist only of diagonal features in the isotope region. The sample G*79 + G**79 (Fig. 4d), which incorporates the heterodimer spectrum, shows features that are not on the diagonal of the 2D IR spectrum. The positive hump at the higher-frequency side of the 13C

18O diagonal transitions are expected are highlighted as rectangles. The G79 sample (Fig. 4a) shows only a weak natural abundance peak, whereas G*79 and G**79 show the spectra of the homodimers G*79/G*79 (Fig. 4b) and G**79/G**79 (Fig. 4c). These spectra consist only of diagonal features in the isotope region. The sample G*79 + G**79 (Fig. 4d), which incorporates the heterodimer spectrum, shows features that are not on the diagonal of the 2D IR spectrum. The positive hump at the higher-frequency side of the 13C 18O mode and the negative dip to the lower-frequency side of the 13C

18O mode and the negative dip to the lower-frequency side of the 13C 16O mode are attributed to cross-peaks, which locate at the corners of the square that they form along with the two diagonal isotopomer levels at 1,589.3 ± 0.6 cm−1 and 1,613.8 ± 0.6 cm−1. The control sample G*94 + G**79 (Fig. 4f) does not show these off-diagonal features. In the difference spectrum (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79, where the G**79/G**79 contribution is removed and the 13C

16O mode are attributed to cross-peaks, which locate at the corners of the square that they form along with the two diagonal isotopomer levels at 1,589.3 ± 0.6 cm−1 and 1,613.8 ± 0.6 cm−1. The control sample G*94 + G**79 (Fig. 4f) does not show these off-diagonal features. In the difference spectrum (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79, where the G**79/G**79 contribution is removed and the 13C 18O spectral region arises from the pure heterodimers G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79 (see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), the cross-peaks become more prominent both above and below the diagonal (Fig. 4e).

18O spectral region arises from the pure heterodimers G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79 (see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), the cross-peaks become more prominent both above and below the diagonal (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 3.

The rephasing magnitude spectra of homodimer G**79 (a), heterodimer G*79 + G**79 (b), and control heterodimer G*94 + G**79 (c). The horizontal line indicates the 13C 18O peak position, and the diagonal line is a slice of the spectrum shown in Fig. 2d. The arrows point to the cross-peaks.

18O peak position, and the diagonal line is a slice of the spectrum shown in Fig. 2d. The arrows point to the cross-peaks.

Fig. 4.

The 2D correlation spectra of GpA TM homodimers G79 (a), G*79 (b), and G**79 (c); heterodimers G*79 + G**79 (d) and (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79 (e); and control sample G*94 + G**79 (f) in 5% SDS. The 13C 16O and 13C

16O and 13C 18O isotopomer diagonal regions are highlighted by rectangular boxes, and the arrows point to the cross-peaks.

18O isotopomer diagonal regions are highlighted by rectangular boxes, and the arrows point to the cross-peaks.

The prominent cross-peak in the spectral region of ωt ≈ 1,615–1,635 cm−1 below the diagonal appearing whenever there is a 13C 18O substitution (Figs. 4 c–f) signifies the coupling of the 13C

18O substitution (Figs. 4 c–f) signifies the coupling of the 13C 18O modes to the unlabeled exciton band states at higher frequencies: Both tertiary and secondary interactions can contribute.

18O modes to the unlabeled exciton band states at higher frequencies: Both tertiary and secondary interactions can contribute.

Angular Measurements.

The relative magnitudes of spectra of (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79 in different polarizations are related to P2(cosθ12), where θ12 is the angle between the transition dipole moments on the two amide groups (30). One measure is the ratio of the 〈xxxx〉 signal amplitude of the 13C 18O diagonal to that of the cross-peak (2.0 ± 0.18). Another is the ratio of 〈xxxx〉/〈xyyx〉 at the cross-peak (see Supporting Text), which has an undetermined sign from P2 = P2(cosθ12). For the choice 〈xyyx〉 > 0, we find 3.9 ± 0.3 from least-squares fitting, and for 〈xyyx〉 < 0 we obtain the ratio −5.0 ± 0.5. In the rephasing magnitude spectra the signal in the cross-peak region (Fig. 3b) is 3.34 times stronger in the 〈xxxx〉 than in the 〈xyyx〉 spectrum. These experimental observations can be combined to yield estimates for the angle θ12 within certain limitations (31). The shape of the G**79 spectrum in the 13C

18O diagonal to that of the cross-peak (2.0 ± 0.18). Another is the ratio of 〈xxxx〉/〈xyyx〉 at the cross-peak (see Supporting Text), which has an undetermined sign from P2 = P2(cosθ12). For the choice 〈xyyx〉 > 0, we find 3.9 ± 0.3 from least-squares fitting, and for 〈xyyx〉 < 0 we obtain the ratio −5.0 ± 0.5. In the rephasing magnitude spectra the signal in the cross-peak region (Fig. 3b) is 3.34 times stronger in the 〈xxxx〉 than in the 〈xyyx〉 spectrum. These experimental observations can be combined to yield estimates for the angle θ12 within certain limitations (31). The shape of the G**79 spectrum in the 13C 18O region (data not shown) distinctly depends on polarization, directly implicating a dimer with split symmetric and antisymmetric components.

18O region (data not shown) distinctly depends on polarization, directly implicating a dimer with split symmetric and antisymmetric components.

Anharmonicities.

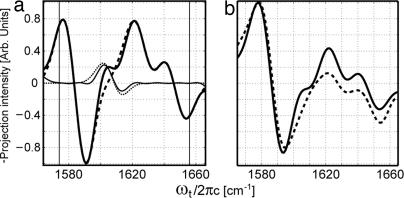

Fig. 5a shows the trace of the 2D IR difference correlation spectrum of (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79 along the ωt axis, averaged over a Gaussian distribution (12 cm−1 full width at half maximum) on ωτ centered at ωτ = 1,590 cm−1, the location of the 13C 18O transition. Fig. 5b compares correlation spectra of G*79 + G**79 and G*94 + G**79 as traces without any subtractions. All of the features except the cross-peak appear in both spectra. The diagonal peaks in these traces were least-squares-fitted to pairs of positive (v = 1→2) and negative (v = 0→1) peaks separated by a frequency gap equal to the diagonal anharmonicity. The off-diagonal anharmonicity from the fits was ΔAB = 3.8 ± 0.6 cm−1, implying that the frequency of the amide-I combination band of the two isotopomers is smaller than the sum of their frequencies. Similar dynamical parameters were assumed for the cross-peak and the 13C

18O transition. Fig. 5b compares correlation spectra of G*79 + G**79 and G*94 + G**79 as traces without any subtractions. All of the features except the cross-peak appear in both spectra. The diagonal peaks in these traces were least-squares-fitted to pairs of positive (v = 1→2) and negative (v = 0→1) peaks separated by a frequency gap equal to the diagonal anharmonicity. The off-diagonal anharmonicity from the fits was ΔAB = 3.8 ± 0.6 cm−1, implying that the frequency of the amide-I combination band of the two isotopomers is smaller than the sum of their frequencies. Similar dynamical parameters were assumed for the cross-peak and the 13C 18O diagonal peak. The pure heterodimers G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79 have a diagonal anharmonicity of the 13C

18O diagonal peak. The pure heterodimers G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79 have a diagonal anharmonicity of the 13C 18O amide-I' mode of Δ = 11.6 ± 0.5 cm−1, and a v = 0→1 transition at 1,589.5 ± 0.3 cm−1.

18O amide-I' mode of Δ = 11.6 ± 0.5 cm−1, and a v = 0→1 transition at 1,589.5 ± 0.3 cm−1.

Fig. 5.

Traces of 2D IR correlation spectra. (a) Least-squares fit to the 12 cm−1-wide trace along the ωt axis of the heterodimer (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79 as described in the text (thick solid line), the fit omitting the cross-peak (thick dashed line), the difference between the solid and the dashed line (thin solid line), and the cross-peak response from least-squares-fitting the whole spectral region between the two vertical lines (thin dotted line). (b) Comparison between the 13C 18O trace of G*79 + G**79 (solid line) and the control sample G*94 + G**79 (dashed line).

18O trace of G*79 + G**79 (solid line) and the control sample G*94 + G**79 (dashed line).

The signals in the cross-peak region discussed above are absent in the sample G*94 + G**79 (Fig. 4f), consistent with residues 79 and 94 (see Fig. 1) having negligible interaction. Comparing Fig. 4 d with f or Fig. 3 b with c, the still obvious 13C 16O region of the 2D IR spectrum of G*94 + G**79 (compared with Fig. 4 a and c) is more extended along the diagonal (see also Fig. 2b, spectrum 5), apparently forming two peaks with the lower frequency one on the edge of the 13C

16O region of the 2D IR spectrum of G*94 + G**79 (compared with Fig. 4 a and c) is more extended along the diagonal (see also Fig. 2b, spectrum 5), apparently forming two peaks with the lower frequency one on the edge of the 13C 18O peak. This result suggests that the structure near Gly94 has a more disordered distribution of amide modes.

18O peak. This result suggests that the structure near Gly94 has a more disordered distribution of amide modes.

Discussion

New structural and dynamical parameters are obtained from the FTIR and 2D IR spectra of both the homodimers and heterodimers of 13C 16O and 13C

16O and 13C 18O substituted TM GpA helices. To describe the homodimer spectra, G*79/G*79 and G**79/G**79 are each treated as pairs of coupled degenerate states considered to be isolated from the remaining 12C

18O substituted TM GpA helices. To describe the homodimer spectra, G*79/G*79 and G**79/G**79 are each treated as pairs of coupled degenerate states considered to be isolated from the remaining 12C 16O amide modes. The heterodimers, treated as pairs of nondegenerate states split by the different isotope shifts, should exhibit cross-peaks that evidence the coupling between the two helices. The exciton model provides a consistent picture of all of the results.

16O amide modes. The heterodimers, treated as pairs of nondegenerate states split by the different isotope shifts, should exhibit cross-peaks that evidence the coupling between the two helices. The exciton model provides a consistent picture of all of the results.

The FTIR spectra of the homodimers are explained by the simple two-level model where the degenerate isotopic levels are split by the tertiary interaction into a symmetric and antisymmetric pair, each of which is completely delocalized over the two helices. The splitting between these states is twice the coupling constant βAB. The two transitions in the 13C 18O region of G**79 therefore indicate that 2∣βAB∣ = 8.6 ± 1.6 cm−1. For such a two-level model, the ratio of the integrated strength of the lower to the higher frequency component is (1 ∓ cosθ12)/(1 ± cosθ12): The upper (lower) sign is used when the coupling is positive (negative). The analysis based on the observed ratio of 1.6 ± 0.1 yields θ12 = 103.0 ± 2.0° for a coupling of +4.3 cm−1 or θ12 = 77.0 ± 2.0° for a coupling of −4.3 cm−1. The amplitudes and polarizations of the homo- and heterodimer 2D IR spectra are consistent with this two-level model.

18O region of G**79 therefore indicate that 2∣βAB∣ = 8.6 ± 1.6 cm−1. For such a two-level model, the ratio of the integrated strength of the lower to the higher frequency component is (1 ∓ cosθ12)/(1 ± cosθ12): The upper (lower) sign is used when the coupling is positive (negative). The analysis based on the observed ratio of 1.6 ± 0.1 yields θ12 = 103.0 ± 2.0° for a coupling of +4.3 cm−1 or θ12 = 77.0 ± 2.0° for a coupling of −4.3 cm−1. The amplitudes and polarizations of the homo- and heterodimer 2D IR spectra are consistent with this two-level model.

The FTIR spectra of the heterodimers also display two transitions, which, according to an exciton model, are expected at frequencies ω+ and ω− given by: ω± = 1/2[(ωA(16) + ωB(18) ± (δAB2 + 4βAB2)1/2], where the frequencies for the 13C 16O and 13C

16O and 13C 18O substitutions on helix A are labeled ωA(16) and ωA(18) and those for B are ωB(16) and ωB(18), and δAB = ωA(16) − ωB(18). If the two amide units are related by a twofold axis of symmetry, then ωA(16) − ωB(18) = ωB(16) − ωA(18), and the heterodimers G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79 become equivalent. Such symmetry also is required for the homodimers to be considered as coupled degenerate states. The first term in ω± is the average frequency of the two isotopically substituted amide modes, which is given from experiment as ≈1,603 cm−1. The second term, which is measured by the difference (ω+ − ω−), is found to be ≈24.5 cm−1. Our results show that the energy difference between the two isotopomer modes of 21.0 ± 0.5 cm−1 increases to 24.5 ± 0.5 cm−1 in the heterodimer sample, which provides another independent measure of the coupling constant magnitude as ∣βAB∣ = 6.3 ± 0.5 cm−1.

18O substitutions on helix A are labeled ωA(16) and ωA(18) and those for B are ωB(16) and ωB(18), and δAB = ωA(16) − ωB(18). If the two amide units are related by a twofold axis of symmetry, then ωA(16) − ωB(18) = ωB(16) − ωA(18), and the heterodimers G**79/G*79 and G*79/G**79 become equivalent. Such symmetry also is required for the homodimers to be considered as coupled degenerate states. The first term in ω± is the average frequency of the two isotopically substituted amide modes, which is given from experiment as ≈1,603 cm−1. The second term, which is measured by the difference (ω+ − ω−), is found to be ≈24.5 cm−1. Our results show that the energy difference between the two isotopomer modes of 21.0 ± 0.5 cm−1 increases to 24.5 ± 0.5 cm−1 in the heterodimer sample, which provides another independent measure of the coupling constant magnitude as ∣βAB∣ = 6.3 ± 0.5 cm−1.

The 2D IR cross-peaks provide the strongest evidence of the delocalization of the vibrational excitations across the two helices. These cross-peaks are a direct measure of the anharmonic coupling ΔAB of the modes, and, because there is no source of anharmonicity between two amide units on different helices except for their electrostatic interaction, the anharmonicity must be related to this coupling. The value of ΔAB can be estimated from a quantum mechanical model (3) that requires as input the diagonal anharmonicity Δ and the separation between the two isotopomer states in the absence of coupling between them. The model yields ΔAB = 4ΔβAB2/δAB2. From the parameters listed in Results, we find from this relationship that ∣βAB∣ = 6.0 cm−1. A finite ΔAB implies that the vibrational spectrum of one helix of the dimer depends on whether the other one is vibrationally excited.

The couplings established by these experiments occur between amide units that are associated with different secondary structures, and it must be a through-space electrostatic interaction. This situation is different from what usually arises with the coupling of amide-I modes that are part of the same secondary structure, because mechanical or through-bond coupling effects are almost certainly absent in the tertiary interaction. Two vibrational modes are considered to be coupled when the energy required to excite one of them depends on whether the other one is excited. This excitation sequence is precisely what is measured from the existence of the cross-peaks in 2D IR spectroscopy. The spatial size of the dominant part of the dynamic charge distribution of the amide-I mode is small compared with separations of >4 Å between the mode centroids in different helices so that the dipole approximation to the electrostatic potential should be approximately correct (32). If consideration of the polarizability of the intervening medium is neglected, the dipolar coupling between two typical amide-I oscillators each having a transition dipole moment of 0.40 debye is 805 κ(Ω)/R3 cm−1, where κ(Ω) is a geometric parameter, −2 ≤ κ(Ω) ≤ 2, and R is the point dipole separation in angstroms. To calibrate this interaction, the typical values for Gly79 amide-I dipoles based on coordinates from the reported GpA dimer structures in other lipids (20) are an angular factor of κ(Ω) = +0.4, a separation R = 4.2 Å, and a coupling approximately +4.3 cm−1. The results from FTIR and 2D IR spectroscopy interpreted by an exciton model are very consistent with values in this range.

The 2D IR spectrum contains information on the orientation of the amide groups. The ratio of the 〈xxxx〉 signal amplitude at the 13C 18O diagonal to that at the cross-peak is predicted (30) to be (9α13/18)/[(4P2 + 5)α13/16], where α13/16 and α13/18 are the absorption coefficients of the 13C

18O diagonal to that at the cross-peak is predicted (30) to be (9α13/18)/[(4P2 + 5)α13/16], where α13/16 and α13/18 are the absorption coefficients of the 13C 16O and 13C

16O and 13C 18O transitions, respectively (α13/16/α13/18 = 1.3). The observed ratio is certainly >1.4, which indicates that P2 is negative. The ratio of the tensor quantities 〈xxxx〉/〈xyyx〉 at the cross-peak is predicted from the same theory to be (4P2 + 5)/3P2, which yields an estimate of P2 as −5/19. The observed cross-peak polarization ratio in the magnitude spectrum of 3.34 is predicted to be (4P2 + 5)/3∣P2∣, which yields still another estimate of a negative-valued P2 as P2 = −5/14. The latter two measurements are consistent with transition dipole angles in the range θ12 = 67–72° or their supplements θ12 = 108–113°. The latter values are in the range for dimer structures from the coordinate sets obtained from NMR (20) but are somewhat larger than expected. The 20 NMR structures of the dimeric TM GpA (Protein Data Bank ID 1AFO) in dodecylphosphocholine micelles give the distance between the Gly79/Gly79 C

18O transitions, respectively (α13/16/α13/18 = 1.3). The observed ratio is certainly >1.4, which indicates that P2 is negative. The ratio of the tensor quantities 〈xxxx〉/〈xyyx〉 at the cross-peak is predicted from the same theory to be (4P2 + 5)/3P2, which yields an estimate of P2 as −5/19. The observed cross-peak polarization ratio in the magnitude spectrum of 3.34 is predicted to be (4P2 + 5)/3∣P2∣, which yields still another estimate of a negative-valued P2 as P2 = −5/14. The latter two measurements are consistent with transition dipole angles in the range θ12 = 67–72° or their supplements θ12 = 108–113°. The latter values are in the range for dimer structures from the coordinate sets obtained from NMR (20) but are somewhat larger than expected. The 20 NMR structures of the dimeric TM GpA (Protein Data Bank ID 1AFO) in dodecylphosphocholine micelles give the distance between the Gly79/Gly79 C O groups as 3.94–5.63 Å and an expected transition dipole–dipole angle varying from 89.8° to 105.0°. The coupling between the two sites from the transition dipole interaction (33) is expected in the NMR range of +2.4 to +4.9 cm−1. The dipole–dipole interaction geometric factor κ(Ω) is simplified to have only two angular constraints and a narrower range if there is a twofold axis compared with four when the dipoles are oriented arbitrarily. The geometric factor takes the form κ(θ12, φ) = 1 + (cosθ12 − 1)P2(cosφ), where φ is the azimuthal angle for one of the dipoles [the other is (φ + π); see Supporting Text]. For κ(θ12, φ) in the NMR range 0.37–0.56, the azimuth is 39° ± 3°, again consistent with the NMR coordinates, which would place it at 35° ± 4°. This analysis locates the transition dipoles quite close to the plane perpendicular to the line joining the dipoles in the two helices. The twofold axis also interchanges the two helical axes of the dimer in the region of the interface. Because the angle that the amide-I transition dipole makes with the helix axis for a perfect α-helix is known to be ≈32° (34), we can establish a simple relationship between (i) the crossing angle of two such dimer helices at the isotopic substitution region, (ii) the experimentally determined angle between the two transition dipoles, and (iii) the angle between the planes formed by the two transition dipoles and that by the two ideal helix axes (see Supporting Text). The latter angle is not strongly dependent on the crossing angle, so we assume that it is robust at the NMR value of −73° (20), which allows a crossing angle of 45° to be determined from the 2D IR data in SDS micelles. The coupling constants and the angles from the 2D IR spectra of GpA in SDS are consistent with a dimer interface structure that is very similar to those reported for dodecylphosphocholine (20), for which presumably the smaller crossing angle of 40° results from differences in the micelles.

O groups as 3.94–5.63 Å and an expected transition dipole–dipole angle varying from 89.8° to 105.0°. The coupling between the two sites from the transition dipole interaction (33) is expected in the NMR range of +2.4 to +4.9 cm−1. The dipole–dipole interaction geometric factor κ(Ω) is simplified to have only two angular constraints and a narrower range if there is a twofold axis compared with four when the dipoles are oriented arbitrarily. The geometric factor takes the form κ(θ12, φ) = 1 + (cosθ12 − 1)P2(cosφ), where φ is the azimuthal angle for one of the dipoles [the other is (φ + π); see Supporting Text]. For κ(θ12, φ) in the NMR range 0.37–0.56, the azimuth is 39° ± 3°, again consistent with the NMR coordinates, which would place it at 35° ± 4°. This analysis locates the transition dipoles quite close to the plane perpendicular to the line joining the dipoles in the two helices. The twofold axis also interchanges the two helical axes of the dimer in the region of the interface. Because the angle that the amide-I transition dipole makes with the helix axis for a perfect α-helix is known to be ≈32° (34), we can establish a simple relationship between (i) the crossing angle of two such dimer helices at the isotopic substitution region, (ii) the experimentally determined angle between the two transition dipoles, and (iii) the angle between the planes formed by the two transition dipoles and that by the two ideal helix axes (see Supporting Text). The latter angle is not strongly dependent on the crossing angle, so we assume that it is robust at the NMR value of −73° (20), which allows a crossing angle of 45° to be determined from the 2D IR data in SDS micelles. The coupling constants and the angles from the 2D IR spectra of GpA in SDS are consistent with a dimer interface structure that is very similar to those reported for dodecylphosphocholine (20), for which presumably the smaller crossing angle of 40° results from differences in the micelles.

The analysis of the 2D IR spectra also provides insight into the distribution of dimer structures as seen through the variance of the coupling constants. The spectral width of the 13C 18O monomer transition, isolated from any resonance coupling with other modes, was found to be ≈11.0 ± 1.0 cm−1 from the difference (G79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79, which displays the G79/G**79 spectrum. When the two 13C

18O monomer transition, isolated from any resonance coupling with other modes, was found to be ≈11.0 ± 1.0 cm−1 from the difference (G79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79, which displays the G79/G**79 spectrum. When the two 13C 18O modes of the homodimer G**79/G**79 couple to each other, the monomer peak splits into the antisymmetric and symmetric components described above and shown in Fig. 2c, but the width of both components is expected to be decreased as a result of the excitation exchange averaging of the inhomogeneous contribution to the width. However, the width can be increased over that of the isolated mode if there is a distribution of coupling constants. In fact, the width did increase to a value of 14.0 cm−1, and the detailed analysis finds a standard deviation of 2.3 cm−1 in the coupling if its distribution was assumed to be Gaussian. This result confirms experimentally a contribution to the static broadening that originates directly from the distribution of dimer geometric configurations in the GpA TM domain. This distribution can be formed by variations in both κ(Ω) and R, which cannot be distinguished by 2D IR until information becomes available from more isotopomers. However, for illustration, if the angles are not varying much, this standard deviation corresponds to an ≈11% variation around the mean distance separating the two coupled amide units. This variance is the maximum possible in the distribution of separations of Gly79 residues in the dimer. It is worth commenting that the standard deviation from the mean separation of the point dipoles obtained from the 20 reported NMR structures is 8% of the mean, so all these structures satisfy the 2D IR criteria.

18O modes of the homodimer G**79/G**79 couple to each other, the monomer peak splits into the antisymmetric and symmetric components described above and shown in Fig. 2c, but the width of both components is expected to be decreased as a result of the excitation exchange averaging of the inhomogeneous contribution to the width. However, the width can be increased over that of the isolated mode if there is a distribution of coupling constants. In fact, the width did increase to a value of 14.0 cm−1, and the detailed analysis finds a standard deviation of 2.3 cm−1 in the coupling if its distribution was assumed to be Gaussian. This result confirms experimentally a contribution to the static broadening that originates directly from the distribution of dimer geometric configurations in the GpA TM domain. This distribution can be formed by variations in both κ(Ω) and R, which cannot be distinguished by 2D IR until information becomes available from more isotopomers. However, for illustration, if the angles are not varying much, this standard deviation corresponds to an ≈11% variation around the mean distance separating the two coupled amide units. This variance is the maximum possible in the distribution of separations of Gly79 residues in the dimer. It is worth commenting that the standard deviation from the mean separation of the point dipoles obtained from the 20 reported NMR structures is 8% of the mean, so all these structures satisfy the 2D IR criteria.

More insight into the heterogeneity of the molecular environments is obtained from a comparison of the 2D IR spectra for micelle-bound GpA samples and the previously reported water-soluble helices. The 2D IR spectra of (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79 in the SDS micellar solution and the Ala13-13C 18O labeled α-helix monomer in aqueous solution (10) are shown together in Fig. 6. The difference between them is striking: The water-soluble helix (Fig. 6b) shows a much rounder peak at a lower transition frequency than the TM helix (Fig. 6a). This result implies that the distribution of amide-I frequencies is much more strongly averaged in the water-soluble helix. This averaging is due to the water dynamics, which cause fluctuations in the amide-I frequencies (35, 36). Clearly water has a greatly diminished averaging effect on the carbonyl groups in the hydrophobic core near Gly79 in the micelle. Recent 2D IR experiments on another TM peptide have provided the residue dependence of this averaging (11). The water-soluble α-helices also showed significant spectral changes occurring within the first 200 fs that were attributed to these amide frequency fluctuations, but this ultrafast dynamics was much less prominent in the current GpA TM helix samples.

18O labeled α-helix monomer in aqueous solution (10) are shown together in Fig. 6. The difference between them is striking: The water-soluble helix (Fig. 6b) shows a much rounder peak at a lower transition frequency than the TM helix (Fig. 6a). This result implies that the distribution of amide-I frequencies is much more strongly averaged in the water-soluble helix. This averaging is due to the water dynamics, which cause fluctuations in the amide-I frequencies (35, 36). Clearly water has a greatly diminished averaging effect on the carbonyl groups in the hydrophobic core near Gly79 in the micelle. Recent 2D IR experiments on another TM peptide have provided the residue dependence of this averaging (11). The water-soluble α-helices also showed significant spectral changes occurring within the first 200 fs that were attributed to these amide frequency fluctuations, but this ultrafast dynamics was much less prominent in the current GpA TM helix samples.

Fig. 6.

Comparison between the rephasing magnitude spectra of GpA TM heterodimer (G*79 + G**79) − 0.25G**79 (a) and of the Ala13-13C 18O-labeled, 25-residue α-helix in water (10) (b). The dashed lines intersect the 13C

18O-labeled, 25-residue α-helix in water (10) (b). The dashed lines intersect the 13C 18O isotopomer peak.

18O isotopomer peak.

Concluding Remarks

2D IR photon echo difference spectroscopy identified homodimers and heterodimers of pairs of 13C 16O- and 13C

16O- and 13C 18O-substituted Gly79 residues on the different helices of the GpA TM dimer. The cross-peaks in the pure heterodimer 2D IR spectrum and the splitting of the homodimer peaks show that the amide-I mode is delocalized over two helices by a coupling in the range 4.3–6.3 cm−1 that arises from through-space interactions. The geometric constraints from these experiments visualize a hydrophobic interface that is consistent with results from NMR and that sets limits on the range of geometries for dimers by specifying properties of a coupling constant distribution. These results provide a promising outlook for 2D IR applications to TM structures and their dynamical properties.

18O-substituted Gly79 residues on the different helices of the GpA TM dimer. The cross-peaks in the pure heterodimer 2D IR spectrum and the splitting of the homodimer peaks show that the amide-I mode is delocalized over two helices by a coupling in the range 4.3–6.3 cm−1 that arises from through-space interactions. The geometric constraints from these experiments visualize a hydrophobic interface that is consistent with results from NMR and that sets limits on the range of geometries for dimers by specifying properties of a coupling constant distribution. These results provide a promising outlook for 2D IR applications to TM structures and their dynamical properties.

Materials and Methods

Samples.

N-Fmoc-1-13C-Gly (99%), 1-13C-Gly (99%), 2H2O (99%), and 18O water (95%) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA) were used to synthesize N-Fmoc-1-13C 18O-Gly (37), and a series of peptides comprising the TM region of GpA were synthesized on a 433A stepwise peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using Fmoc chemistry according to Fisher and Engelman (38), except that HATU [2-(1H-7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)–1,1,3,3-tetramethyl uronium hexafluorophosphate methanaminium] was used as an activator and double coupling was applied only at positions 73–75, 87–88, and 90–91. The peptide sequence included residues 73–95 of human GpA and was flanked by two Lys residues at each end and amidated at the C terminus. The terminal Tyr93 residue was mutated to Trp for improved detection. The resulting 27-residue GpA TM peptide sequence was KKITLIIFG79VMAGVIGTILLISWG94IKK, in which the carbonyl of Gly79 that participates intimately at the dimer helix–helix interface was selectively isotopically labeled with 13C

18O-Gly (37), and a series of peptides comprising the TM region of GpA were synthesized on a 433A stepwise peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using Fmoc chemistry according to Fisher and Engelman (38), except that HATU [2-(1H-7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)–1,1,3,3-tetramethyl uronium hexafluorophosphate methanaminium] was used as an activator and double coupling was applied only at positions 73–75, 87–88, and 90–91. The peptide sequence included residues 73–95 of human GpA and was flanked by two Lys residues at each end and amidated at the C terminus. The terminal Tyr93 residue was mutated to Trp for improved detection. The resulting 27-residue GpA TM peptide sequence was KKITLIIFG79VMAGVIGTILLISWG94IKK, in which the carbonyl of Gly79 that participates intimately at the dimer helix–helix interface was selectively isotopically labeled with 13C 16O or 13C

16O or 13C 18O, and another peptide with 13C

18O, and another peptide with 13C 16O at Gly94 was prepared. The peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC using a protein-C4 preparative column with an i.d. of 25 mm (Grace Vydac, Hesperia, CA) and a gradient of solvents A (0.1% TFA in water) and B (0.1% TFA in 60% isopropanol/40% acetonitrile). The peptides were then lyophilized. The dry peptides were resolubilized in a 5% SDS detergent solution (45 mM sodium phosphate, uncorrected pH ≈7.15, in 2H2O) at a final concentration of 5 mg/ml (1.7 mM). This procedure promotes GpA dimerization even at very high SDS concentrations (39).

16O at Gly94 was prepared. The peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC using a protein-C4 preparative column with an i.d. of 25 mm (Grace Vydac, Hesperia, CA) and a gradient of solvents A (0.1% TFA in water) and B (0.1% TFA in 60% isopropanol/40% acetonitrile). The peptides were then lyophilized. The dry peptides were resolubilized in a 5% SDS detergent solution (45 mM sodium phosphate, uncorrected pH ≈7.15, in 2H2O) at a final concentration of 5 mg/ml (1.7 mM). This procedure promotes GpA dimerization even at very high SDS concentrations (39).

2D IR Spectroscopic Method.

The 2D IR measurement required ultrafast pulses, their four-wave mixing to generate the vibrational photon echo, and a heterodyned scheme to measure the generated field. Details can be found in previous reports from this laboratory (8). Briefly, an 800-nm pulse with a duration of <45-fs from a Ti:sapphire laser-amplifier system pumped a two-stage optical parametric amplifier to generate femtosecond mid-IR, 6-μm pulses, which were split into three 400-nJ, transform-limited 75-fs pulses with wavevectors k⇑1, k⇑2, and k⇑3 and a bandwidth of ≈178 cm−1. The emitted photon echo signal in the direction −k⇑1 + k⇑2 + k⇑3 was collimated with a fourth pulse that preceded it by 1.5 ps and then dispersed and recorded by an array detector as a function of the interval between incident pulses 1 and 2 (τ) and a waiting time between pulses 2 and 3 (T), which was fixed at 300 fs. The rephasing signal has pulse 1 arriving before pulse 2, whereas in nonrephasing this ordering is reversed. After double Fourier transform, the 2D correlation spectrum is the sum of the rephasing and nonrephasing spectra. The frequency step is 1.1 cm−1. The center frequency of the incident pulses was chosen at the isotopomer region. The polarizations pi of the pulses i = 1–4 are indicated explicitly in the tensor component 〈p1p2p3p4〉. All data shown in the figures are for the 〈xxxx〉 configuration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sungwook Choi (University of Pennsylvania) for his synthesis of the 13C 18O-Fmoc-Gly and Profs. Nien-Hui Ge and Igor Rubtsov for valuable discussions. The research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM12592 and NSFCHE (to R.M.H.) and 5P01 GM48130 (to R.M.H. and W.F.D.) and National Institutes of Health Resource RR001348.

18O-Fmoc-Gly and Profs. Nien-Hui Ge and Igor Rubtsov for valuable discussions. The research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM12592 and NSFCHE (to R.M.H.) and 5P01 GM48130 (to R.M.H. and W.F.D.) and National Institutes of Health Resource RR001348.

Abbreviations

- GpA

Glycophorin A

- TM

transmembrane

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hamm P, Lim M, Hochstrasser RM. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:6123–6138. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asplund MC, Zanni MT, Hochstrasser RM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8219–8224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140227997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamm P, Hochstrasser RM. In: Ultrafast Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy. Fayer MD, editor. New York: Dekker; 2001. pp. 273–347. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukamel S. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2000;51:691–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khalil M, Demirdoven N, Tokmakoff A. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:5258–5279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonas DM. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2003;54:425–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.54.011002.103907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woutersen S, Hamm P. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:2727–2737. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YS, Wang J, Hochstrasser RM. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:7511–7521. doi: 10.1021/jp044989d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woutersen S, Hamm P. J Chem Phys. 2001;115:7737–7743. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang C, Hochstrasser RM. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:18652–18663. doi: 10.1021/jp052525p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee P, Kass I, Arkin I, Zanni MT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3528–3533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508833103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volkov V, Hamm P. Biophys J. 2004;87:4213–4225. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung HS, Khalil M, Smith AW, Ganim Z, Tokmakoff A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:612–617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408646102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Londergan CH, Wang J, Axelsen PH, Hochstrasser RM. Biophys J. 2006;90:4672–4685. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.075812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demirdoven N, Cheatum CM, Chung HS, Khalil M, Knoester J, Tokmakoff A. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7981–7990. doi: 10.1021/ja049811j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Chen J, Hochstrasser RM. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:7545–7555. doi: 10.1021/jp057564f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang C, Wang J, Kim YS, Charnley AK, Barber-Armstrong W, Smith AB, III, Decatur SM, Hochstrasser RM. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:10415–10427. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popot J-L, Engelman DM. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4031–4037. doi: 10.1021/bi00469a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacKenzie KR. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1931–1977. doi: 10.1021/cr0404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKenzie KR, Prestegard JH, Engelman DM. Science. 1997;276:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Javadpour MM, Eilers M, Groesbeek M, Smith SO. Biophys J. 1999;77:1609–1618. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senes A, Engel DE, DeGrado WF. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:465–479. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sansom MSP, Sankararamakrishnan R, Kerr ID. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:624–631. doi: 10.1038/nsb0895-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzyk P, Hubbard RE. Biophys J. 1995;69:2419–2442. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80112-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottschalk K-E. Structure (London) 2005;13:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kukol A, Adams PD, Rice LM, Brunger AT, Arkin IT. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:951–962. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorgen PL, Hu Y, Guan L, Kaback HR, Girvin ME. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14037–14040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182552199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleishman SJ, Harrington S, Friesner RA, Honig B, Ben-Tal N. Biophys J. 2004;87:3448–3459. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manas ES, Getahun Z, Wright WW, DeGrado WF, Vanderkooi JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9883–9890. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochstrasser RM. Chem Phys. 2001;266:273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hahn S, Lee H, Cho M. J Chem Phys. 2004;121:1849–1865. doi: 10.1063/1.1763889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Hochstrasser RM. Chem Phys. 2004;297:195–219. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torii H, Tasumi M. J Chem Phys. 1992;96:3379–3387. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Adv Protein Chem. 1986;38:181–364. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanni MT, Asplund MC, Hochstrasser RM. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:4579–4590. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt JR, Corcelli SA, Skinner JL. J Chem Phys. 2004;121:8887–8896. doi: 10.1063/1.1791632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torres J, Kukol A, Goodman JM, Arkin IT. Biopolymers. 2001;59:396–401. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(200111)59:6<396::AID-BIP1044>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher LE, Engelman DM. Anal Biochem. 2001;293:102–108. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher LE, Engelman DM, Sturgis JN. Biophys J. 2003;85:3097–3105. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.