Abstract

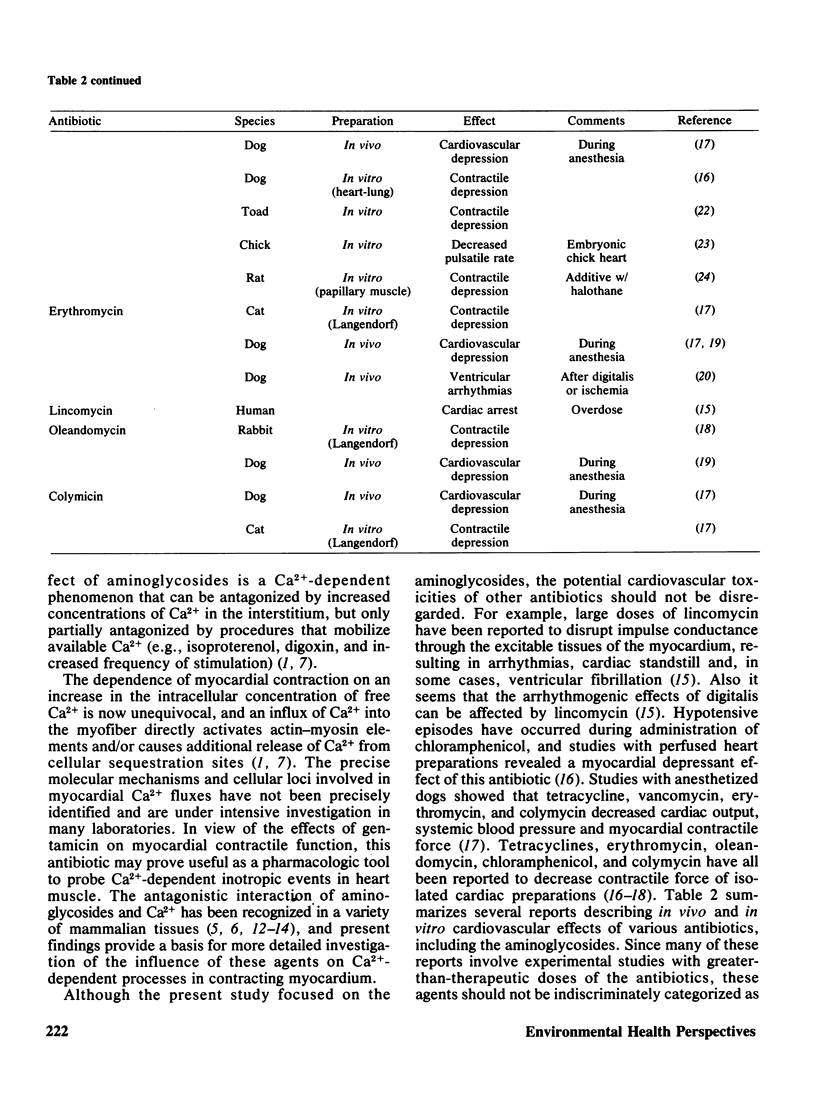

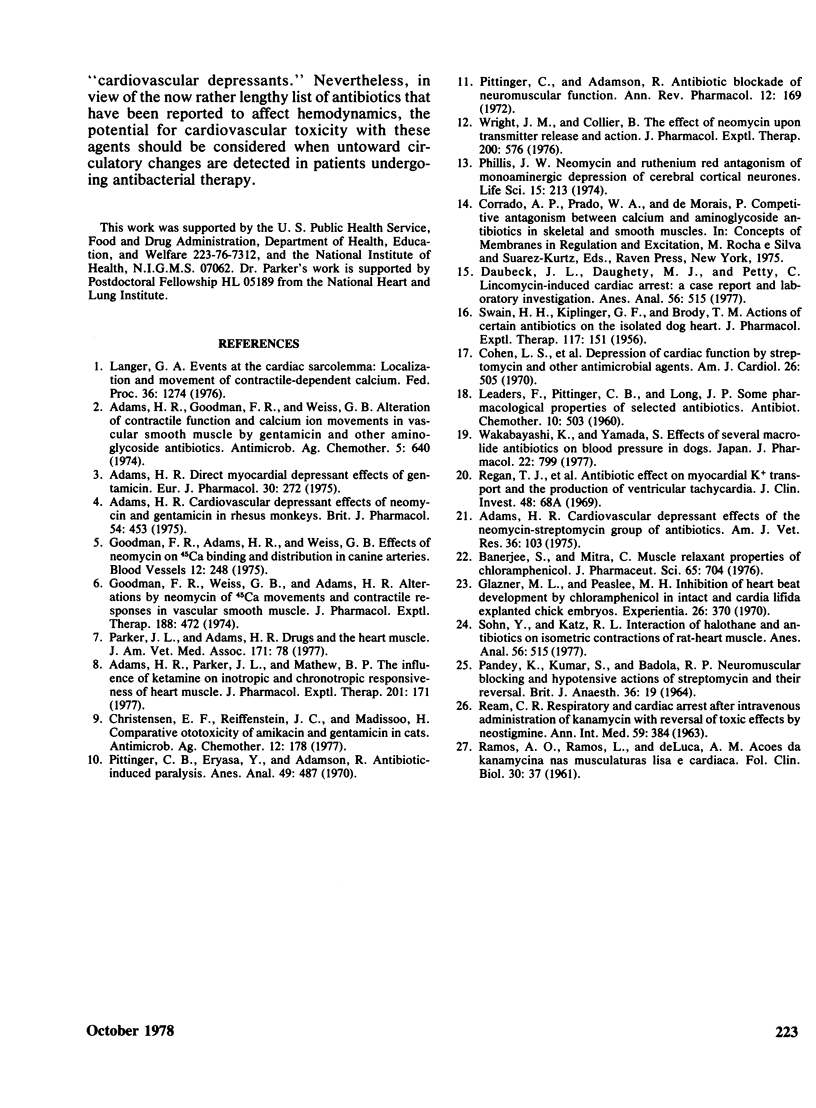

Isolated heart muscle preparations are useful in the study of cardiac toxicities of drugs and environmental chemicals: such tissues allow assessment of chemical effects on heart muscle that is free from indirect in vivo influences that can mask or even accentuate cardiac responses measured in the intact animal. In the present study, left atria of guinea pigs were used to demonstrate a direct cardiac depressant effect of greater-than-therapeutic concentrations of several aminoglycoside antibiotics. The toxic effect of these antibiotics seems to be a calcium-dependent event, and may prove useful to characterize contractile responses of the heart. Other antibiotic agents can also depress cardiovascular function, as summarized in this report, but mechanisms of action have not been clearly defined.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams H. R. Cardiovascular depressant effects of neomycin and gentamicin in rhesus monkeys. Br J Pharmacol. 1975 Aug;54(4):453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1975.tb07591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams H. R. Cardiovascular depressant effects of the neomycin-streptomycin group of antibiotics. Am J Vet Res. 1975 Jan;36(1):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams H. R. Direct myocardial depressant effects of gentamicin. Eur J Pharmacol. 1975 Feb;30(2):272–279. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(75)90110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams H. R., Goodman F. R., Weiss G. B. Alteration of contractile function and calcium ion movements in vascular smooth muscle by gentamicin and other aminoglycoside antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1974 Jun;5(6):640–646. doi: 10.1128/aac.5.6.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams H. R., Parker J. L., Mathew B. P. The influence of ketamine on inotropic and chronotropic responsiveness of heart muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977 Apr;201(1):171–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Mitra C. Muscle relaxant properties of chloramphenicol. J Pharm Sci. 1976 May;65(5):704–708. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600650519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen E. F., Reiffenstein J. C., Madissoo H. Comparative ototoxicity of amikacin and gentamicin in cats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977 Aug;12(2):178–184. doi: 10.1128/aac.12.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. S., Wechsler A. S., Mitchell J. H., Glick G. Depression of cardiac function by streptomycin and other antimicrobial agents. Am J Cardiol. 1970 Nov;26(5):505–511. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanzer M. L., Peaslee M. H. Inhibition of heart beat development by chloramphenicol in intact and Cardia bifida explanted chick embryos. Experientia. 1970 Apr 15;26(4):370–371. doi: 10.1007/BF01896893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman F. R., Adams H. R., Weiss G. B. Effects of neomycin on 45Ca binding and distribution in canine arteries. Blood Vessels. 1975;12(4):248–260. doi: 10.1159/000158060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman F. R., Weiss G. B., Adams H. R. Alterations by neomycin of 45Ca movements and contractile responses in vascular smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1974 Feb;188(2):472–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEADERS F., PITTINGER C. B., LONG J. P. Some pharmacological properties of selected antibiotics. Antibiot Chemother (Northfield) 1960 Aug;10:503–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer G. A. Events at the cardiac sarcolemma: localization and movement of contractile-dependent calcium. Fed Proc. 1976 May 1;35(6):1274–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. L., Adams H. R. Drugs and the heart muscle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977 Jul 1;171(1):78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillis J. W. Neomycin and ruthenium red antagonism of monoaminergic depression of cerebral cortical neurones. Life Sci. 1974 Jul 15;15(2):213–222. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(74)90209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittinger C., Adamson R. Antibiotic blockade of neuromuscular function. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1972;12:169–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.12.040172.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REAM C. R. RESPIRATORY AND CARDIAC ARREST AFTER INTRAVENOUS ADMINISTRATION OF KANAMYCIN WITH REVERSAL OF TOXIC EFFECTS BY NEOSTIGMINE. Ann Intern Med. 1963 Sep;59:384–387. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-59-3-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWAIN H. H., KIPLINGER G. F., BRODY T. M. Actions of certain antibiotics on the isolated dog heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1956 Jun;117(2):151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn Y. Z., Katz R. L. Interaction of halothane and antibiotics on isometric contractions on rat-heart muscle. Anesth Analg. 1977 Jul-Aug;56(4):515–521. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi K., Yamada S. Effects of several macrolide antibiotics on blood pressure of dogs. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1972 Dec;22(6):799–807. doi: 10.1254/jjp.22.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. M., Collier B. The effects of neomycin upon transmitter release and action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977 Mar;200(3):576–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]