Abstract

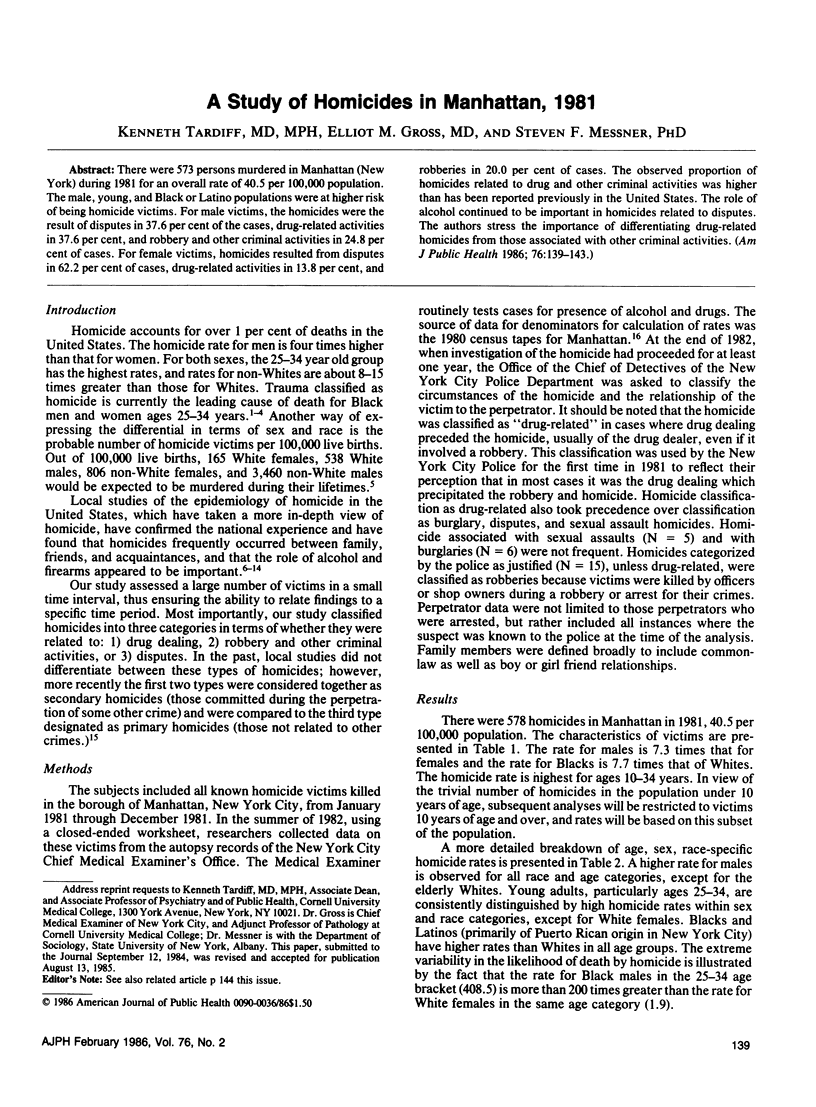

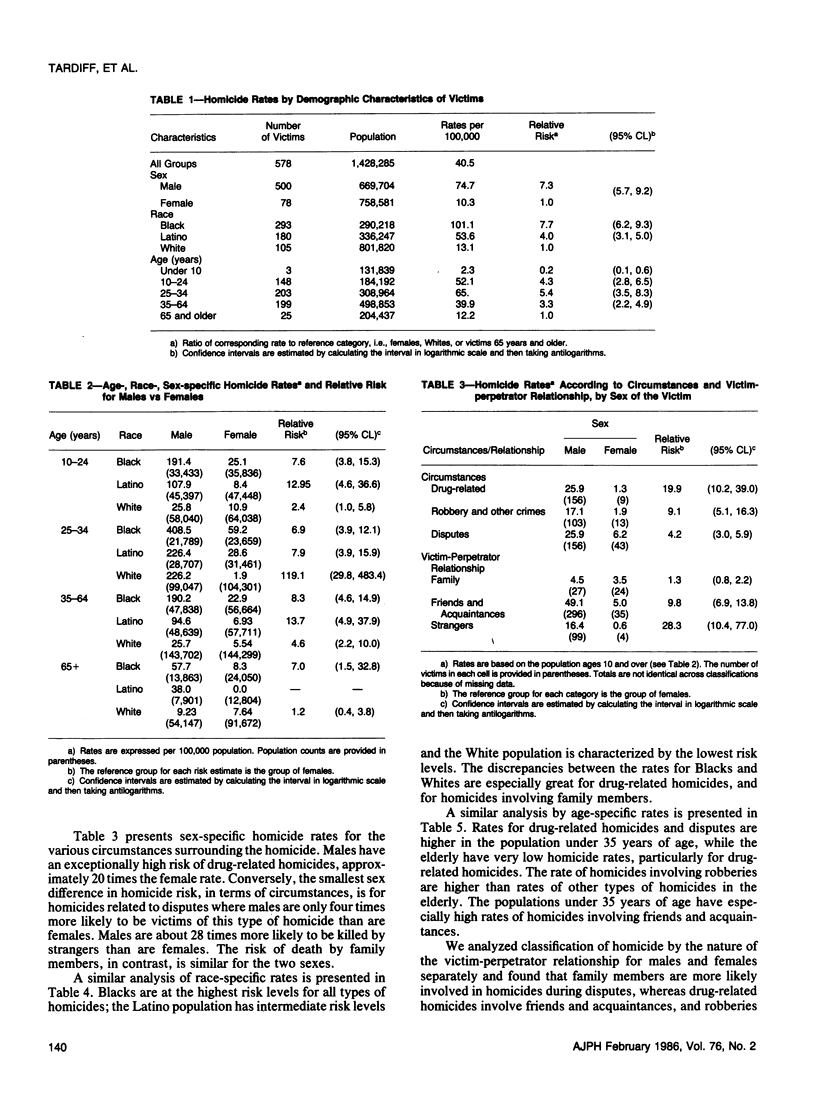

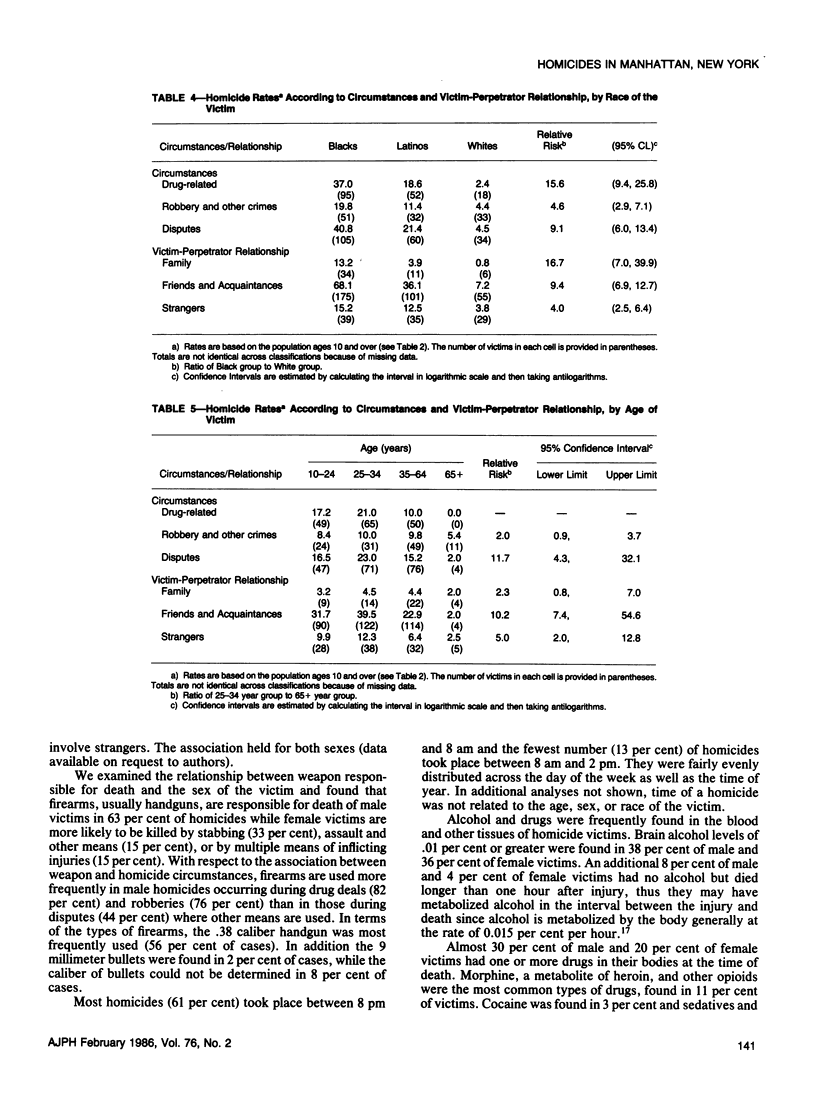

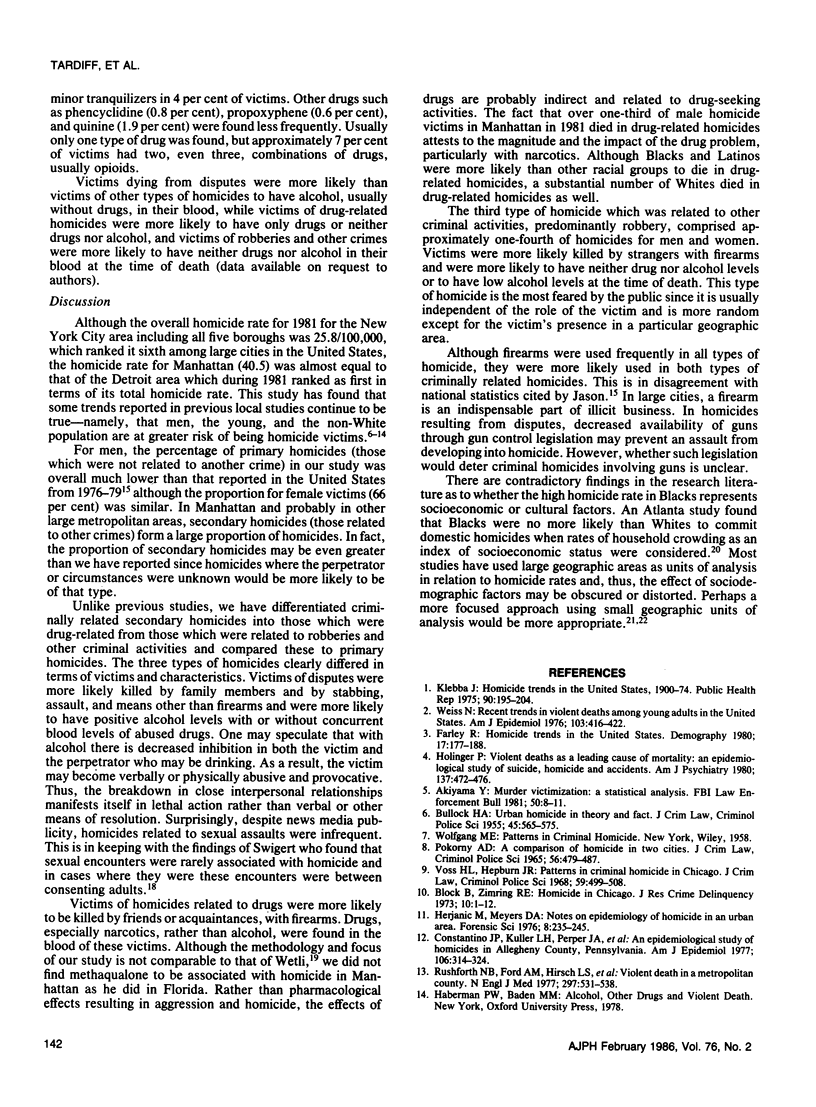

There were 573 persons murdered in Manhattan (New York) during 1981 for an overall rate of 40.5 per 100,000 population. The male, young, and Black or Latino populations were at higher risk of being homicide victims. For male victims, the homicides were the result of disputes in 37.6 per cent of the cases, drug-related activities in 37.6 per cent, and robbery and other criminal activities in 24.8 per cent of cases. For female victims, homicides resulted from disputes in 62.2 per cent of cases, drug-related activities in 13.8 per cent, and robberies in 20.0 per cent of cases. The observed proportion of homicides related to drug and other criminal activities was higher than has been reported previously in the United States. The role of alcohol continued to be important in homicides related to disputes. The authors stress the importance of differentiating drug-related homicides from those associated with other criminal activities.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Centerwall B. S. Race, socioeconomic status, and domestic homicide, Atlanta, 1971-72. Am J Public Health. 1984 Aug;74(8):813–815. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.8.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino J. P., Kuller L. H., Perper J. A., Cypess R. H. An epidemiologic study of homicides in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Am J Epidemiol. 1977 Oct;106(4):314–324. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley R. Homicide trends in the United States. Demography. 1980 May;17(2):177–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herjanic M., Meyer D. A. Notes on epidemiology of homicide in an urban area. Forensic Sci. 1976 Nov-Dec;8(3):235–245. doi: 10.1016/0300-9432(76)90137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holinger P. C. Violent deaths as a leading cause of mortality: an epidemiologic study of suicide, homicide, and accidents. Am J Psychiatry. 1980 Apr;137(4):472–476. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason J., Strauss L. T., Tyler C. W., Jr A comparison of primary and secondary homicides in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1983 Mar;117(3):309–319. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebba A. J. Homicide trends in the United States, 1900-74. Public Health Rep. 1975 May-Jun;90(3):195–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushforth N. B., Ford A. B., Hirsch C. S., Rushforth N. M., Adelson L. Violent death in a metropolitan county. Changing patterns in homicide (1958-74). N Engl J Med. 1977 Sep 8;297(10):531–538. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197709082971004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swigert V. L., Farrell R. A., Yoels W. C. Sexual homicide: social, psychological, and legal aspects. Arch Sex Behav. 1976 Sep;5(5):391–401. doi: 10.1007/BF01541332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N. S. Recent trends in violent deaths among young adults in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1976 Apr;103(4):416–422. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]