Abstract

Both the Human papillomavirus (HPV) major (L1) and minor (L2) capsid proteins have been well investigated as potential vaccine candidates. The L1 protein first oligomerizes into pentamers, and these capsomers assemble into virus-like particles (VLPs) that are highly immunogenic. Here we examine the potential of using HPV type 16 (HPV-16) L1 subunits to display a well-characterized HPV-16 L2 epitope (LVEETSFIDAGAP), which is a common-neutralizing epitope for HPV types 6 and 16, in various regions of the L1 structure. The L2 sequence was introduced by PCR (by replacing 13 codons) into sequences coding for L1 surface loops D-E (ChiΔC-L2), E-F (ChiΔA-L2), and an internal loop C-D (ChiΔH-L2); into the h4 helix (ChiΔF-L2); and between h4 and β-J structural regions (ChiΔE-L2). The chimeric protein product was characterized using a panel of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that bind to conformational and linear epitopes, as well as a polyclonal antiserum raised to the L2 epitope. All five chimeras reacted with the L2 serum. ChiΔA-L2, ChiΔE-L2, and ChiΔF-L2 reacted with all the L1 antibodies, ChiΔC-L2 did not bind H16:V5 and H16:E70, and ChiΔH-L2 did not bind any conformation-dependent MAb. The chimeric particles elicited high-titer anti-L1 immune responses in BALB/c mice. Of the five chimeras tested only ChiΔH-L2 did not elicit an L2 response, while ChiΔF-L2 elicited the highest L2 response. This study provides support for the use of PV particles as vectors to deliver various epitopes in a number of locations internal to the L1 protein and for the potential of using chimeric PV particles as multivalent vaccines. Moreover, it contributes to knowledge of the structure of HPV-16 L1 VLPs and their derivatives.

Papillomaviruses (PVs) belong to the taxonomic family Papillomaviridae and have a double-stranded circular DNA genome with a typical size of ∼8 kb (36). PVs have nonenveloped isometric virions 55 nm in diameter. The viral capsid contains major (L1) and minor (L2) capsid proteins at a molar ratio of 30 to 1, with 360 L1 molecules arranged as 72 pentamers or capsomers, in a T = 7d lattice (44). L2 proteins are presumed to associate with the penton vertices of the capsomers. Some human PV (HPV) types infecting the mucosal epithelium (such as HPV type 6 [HPV-6] and HPV-11) cause benign condylomas, but a large number of types (HPV-16, -18, -33, -35, -39, -45, -52, -58, and -59, among others) can cause cervical cancer. Of these high-risk types, HPV-16 is the most prevalent, found in approximately 50% of cases (44).

In recent years there has been tremendous progress in the development of prophylactic vaccines for HPV types that cause genital infections. PV virus-like particles (VLPs), made either from expression of the capsid genes L1 alone or by coexpression of L1 and L2, have been proven to induce protective immunity in animal models (1, 8, 13, 20, 38, 39) and are currently in clinical trials for the prevention of HPV infections (12, 29, 35, 43).

Numerous serological studies have shown that there is a strong immune response to the L1 protein in humans after infection with genital HPV types. The response is long-term but type specific (2, 3, 20, 40). Most of the neutralizing epitopes previously identified are nonlinear and conformation dependent, and their surface location and amino acid composition have been partially characterized by monoclonal antibody (MAb) binding and immunization studies. In HPV-16, the L1 residues 50, 266, and 282 are considered to be vital for the binding of the neutralizing MAbs H16:V5 and H16:E70 (41). Linear epitopes that are identified by MAbs H16:J4 (amino acids [aa] 261 to 280) and H16:I23 (aa 111 to 130) show weak cross-neutralizing activity for HPV-18, -31, -33, -45, -55, and -59 in addition to HPV-16 (9).

There are a number of studies describing the use of PV VLPs to deliver and/or display foreign epitopes (11, 22, 23, 25, 27, 37). L1 C-terminal fusion chimeras have worked well in presenting the epitopes of the HPV-16 E7 protein (15, 25), human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) p18 cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes, and HIV-1 gp120 (22, 23) and HIV-1 gp41 epitopes (37), in HPV-11, HPV-16, and bovine PV-1. Attempts have been made to insert epitopes into the core sequences of the PV L1, with the result of capsomers rather than VLPs being formed (37). There are convincing data in the literature to indicate that capsomers are significantly immunogenic and in fact capable of eliciting a neutralizing immune response (10, 31, 42).

A common-neutralizing epitope for HPV-6 and -16 is present between aa 108 and 120 (LVEETSFIDAGAP) of the HPV-16 minor capsid protein, L2 (17). Sera of mice immunized with this peptide cross-reacted with L1/L2 capsids of HPV-6, -11, and -18 (16-18). Preincubation of monkey COS-1 cells with the synthetic L2 epitope reduces the susceptibility of COS-1 cells to infection with HPV-16 L1/L2 pseudovirions (19).

Based on the reports of cross-reactivity of the neutralizing L2 epitope characterized by Kawana et al. (16-19) and the evidence that VLPs can be used to deliver foreign epitopes (14, 15, 22, 23, 25, 26, 28, 32, 34, 37), we decided to investigate the possibility of making chimeric vaccine candidates with the L2 epitope displayed on HPV-16 L1 particles, which hopefully maintained the neutralizing MAb H16:V5 and H16:E70-binding epitopes. We constructed five HPV-16 L1 chimeras that displayed the L2 epitope as replacement sequences, expressed them in insect cells using a baculovirus expression system, and characterized the chimeric products with a panel of MAbs. This study opens various avenues for multivalent vaccine development using PV particles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of chimeric constructs and expression in insect cells by recombinant baculovirus.

Chimeric constructs were prepared by PCR mutagenesis of the 39 bp regions to be replaced, with the primers being designed with the 3′ end coding for the L2 peptide (Table 1). The HPV-16 L1 gene (South African isolate; GenBank accession no. AY177679) cloned in the pSK plasmid vector (Stratagene Cloning Systems) was used as a template. The mutagenesis was carried out using a two-step PCR system. First, a chimeric template was generated using the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche) that is suited for the accurate amplification of large DNA templates. The PCR mixture (50 μl) was digested with DpnI restriction endonuclease (to digest methylated template DNA); 5 μl of this was used in the second step using Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega). DH5α Escherichia coli competent cells were transformed with the amplified DNA and the chimeric product was sequenced.

TABLE 1.

Summary of chimeric constructs, regions where the L2 epitope was displayed, and primers used to construct them

| Chimeric construct | Nucleotide position of L2 | Amino acid position of L2 | Region | Primer used to insert the L2 epitopea-LVEETSFIDAGAP (5′-TTA GTG GAA GAA ACT AGT TTT ATT GAT GCT GGT GCA CCA-3′)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Sequence | ||||

| ChiΔA-L2 | 522-558 | 174-186 | Loop E-F | Forward | 5′-TATTGATGCTGGTGCACCACCATTAGAGTTAATAAACACAGTTATTCAGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAACTAGTTTCTTCCACTAAGGATCCTTTGCCCCAGTGTTC-3′ | ||||

| ChiΔC-L2 | 393-429 | 131-143 | Loop D-E | Forward | 5′-TTTTATTGATGCTGGTGCACCAAGAGAATGTATATCTATGGATTACAAACAAACAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTAGTTTCTTCCACTAATTCTGTGTCATCCAATTTATTTAATAAAGGATGGCCACTAATG-3′ | ||||

| ChiΔE-L2 | 1293-1329 | 431-443 | Coil between h4 and β-J | Forward | 5′-TATTGATGCTGGTGCACCATACACTTTTTGGGAAGTAAATTTAAAGGAAAAG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAACTAGTTTCTTCCACTAATTTTTGACAAGCAATTGCCTGGG-3′ | ||||

| ChiΔF-L2 | 1242-1278 | 414-426 | h4 helix | Forward | 5′-TTTTATTGATGCTGGTGCACCAGCTTGTCAAAAACATACACCTCCAGCACCT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTAGTTTCTTCCACTAATGTGCCTCCTGGGGGAGGTTGTAGACC-3′ | ||||

| ChiΔH-L2 | 243-279 | 81-93 | Loop C-D | Forward | 5′-TATTGATGCTGGTGCACCAGATACACAGCGGCTGGTTTGGGC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAACTAGTTTCTTCCACTAAGGGGTCAGGTAAATGTATTCTAAATACCCTG-3′ | ||||

L2 epitope, LVEETSFIDAGAP. Underlined regions are part of the L2 epitope.

The L1 chimeric constructs were expressed in insect cells using the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Life Technologies). The chimeras were cloned into pFastbac1 vector (SalI/XbaI restriction sites). The DNA from these clones was used to transfect DH10bac E. coli cells to prepare bacmid clones. The bacmid DNA was transfected into sf21 insect cells using Cellfectin (Life Technologies). The basic Bac-to-Bac protocol was followed to amplify the recombinant virus and to infect the sf21insect cells for expression of the chimeric VLPs.

Preparation of chimeric HPV-16 L1 particles.

The infected insect cells were spun down at 1,000 × g, resuspended in high-salt phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.5 M NaCl) and sonicated four times at 5-s intervals. The sonicated material was overlaid onto a 40% sucrose cushion and pelleted at 100,000 × g for 3 h. The pellet was resuspended in CsCl buffer (PBS with 0.4g/ml CsCl) with sonication (four times at 5-s intervals). The suspension was centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 10°C for 24 h in a Beckman SW50.1 rotor. Fractions (500 μl) were collected and analyzed by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using MAb H16:J4 (binds linear epitope 261 to 280) (7). Fractions that bound MAb H16:J4 were pooled and dialyzed against PBS at 4°C overnight.

Expression and purification of HPV-16 L2 protein in E. coli.

The HPV-16 L2 gene was amplified by PCR from an HPV-16 L2-E2-E7 construct (provided by J. Schiller, National Institutes of Health) and cloned into the pProEx HT Prokaryotic Expression Vector (Life Technologies). Competent DH5α E coli cells were transformed and protein expression was induced as per manufacturer's recommendations. The induced cells were pelleted and lysed (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5], 5 mM 2-mecaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, lysozyme [10 μg/μl]) on ice for half an hour. Triton X-100 (1% final concentration) was added and incubated at 37°C; the nucleic acid was digested using 5 μl of DNase I (1 mg/ml) and 5 μl of RNase A (10 mg/ml) per 1 ml of lysis mix at room temperature for 30 min. The L2 protein (insoluble) was pelleted at 12,000 × g for 5 min and resuspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and 0.5% Triton X-100 buffer. The L2 protein was pelleted at 12,000 × g and resuspended in PBS.

Western blot analysis of the chimeric protein product.

The chimeric protein was denatured for 10 min at 100°C in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) disruption solution. The denatured chimeric protein was resolved on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel. The resolved gel was transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane by semidry electrophoresis (Bio-Rad) for 25 min at 25 V. The membrane was blocked using 1% nonfat milk for 2 h and incubated with primary antibody at a dilution of 1:1,000 overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 and probed, with alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary antibody diluted 1:2,000, for 1 h at room temperature. Reaction was detected colorimetrically using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-phosphate (BCIP) and 4-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) substrates.

Antibody characterization of chimeric particles by ELISA.

A dilution series of each of the chimeric protein products was tested against MAb H16:J4, and dilutions that gave similar absorbances by ELISA were selected in order to normalize the antigen concentrations. The normalized dilutions were used for further antibody characterization by ELISA. ELISA plates were coated with the chimeric protein at the appropriate dilution, and the plates were stored overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed four times with PBS and blocked with 1% nonfat milk. The MAbs and polyclonal antibodies were diluted at 1:500 in PBS-milk and allowed to bind to the chimeric proteins for 2 h at room temperature, and this was followed by four stringent washes. The bound primary antibody was probed with the relevant alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse). The binding was detected using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma), and the absorbances on the ELISA plate were read at 405 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy of chimeric particles.

The chimeric particles were viewed either after direct adsorption onto carbon-coated copper grids or after immunotrapping with preadsorbed H16:J4 MAb (binds L1 linear epitope from aa 261 to 280) at a dilution of 1:50. The grids were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and viewed using a JEOL 200CX transmission electron microscope.

Immunization of mice with chimeric protein particles.

Six groups of five mice were used for this study. The 8-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized with chimeric protein (100 μg) at three subcutaneous sites with Freund's incomplete adjuvant (1:1). The immunizations were done at 0, 2, and 4 weeks, and the serum samples (200 μl) were collected at weeks 0 (preimmunization), 1, 3, and 5.

Serum analysis for immune response to HPV-16 L1.

ELISA plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl of baculovirus-produced native HPV-16 L1 VLPs at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. The plates were washed three times with PBS, blocked with 1% nonfat milk (300 μl) in PBS, and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After washing, the ELISA plates were probed with serum (100 μl) diluted in 1% nonfat milk and incubated for 2 h. Anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (DAKO) (100 μl diluted 1:2,000 in 1% nonfat milk) was added to the ELISA plates after washing four times with PBS. The plates were incubated for an hour at 37°C and washed four times with PBS. 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl-benzidine substrate (100 μl per well) (TMB Microwell Peroxidase Substrate System; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) was added, and plates allowed to react in the dark for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 100 μl of 0.5 M H2SO4/well, and the optical density was read at 450 nm.

Serum analysis for immune response to HPV-16 L2 protein.

The L2 protein was denatured for 10 min at 100°C in SDS disruption solution and resolved on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel. The resolved gel was transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane by semidry electrophoresis (Bio-Rad) for 45min at 17 V. The membrane was blocked using 1% nonfat milk protein for 2 h and incubated overnight at 4°C with L2 polyclonal antibody (against the L2 peptide spanning aa 108 to 120) at a dilution of 1:1,000 for the positive control, and 1:100 for the mouse sera, to detect L2 epitope immune response. The membrane was washed with PBS/Tween and probed with alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary antibody at 1:5,000 for 1 h at room temperature. This was detected by a colorimetric reaction using NBT and BCIP.

RESULTS

Synthesis and expression of chimeric constructs.

Five regions of the L1 structure identified as having potential for displaying the L2 epitope were selected for this study (Table 1). The neutralizing L2 epitope sequence was introduced by a PCR-based strategy, involving replacing 13 codons in the L1 gene sequences coding for surface loops D-E (ChiΔC-L2) and E-F (ChiΔA-L2), an internal loop C-D (ChiΔH-L2), the h4 helix (ChiΔF-L2), and the region between the h4 helix and the β-J sheet (ChiΔE-L2) (Table 1). The C-D loop is not surface exposed in VLPs and would only putatively be exposed in pentameric capsomers. Multiple sequence alignment indicates that the C-D loop and the h4 helix are highly conserved between PV types. Secondary structure prediction data indicated that the h4 helix would be destroyed by substitution of the L2 epitope into this region. In brief, the L2 sequence in ChiΔA-L2 is probably displayed on the outer rim of the pentamer head, ChiΔC-L2 on the pentamer head, ChiΔE-L2 and ChiΔF-L2 on the C-terminal arm, and ChiΔH-L2 on an internal loop at the base of the pentamer.

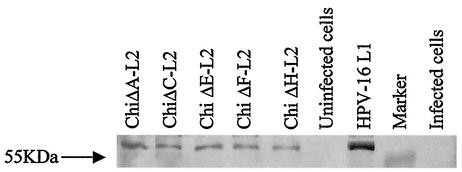

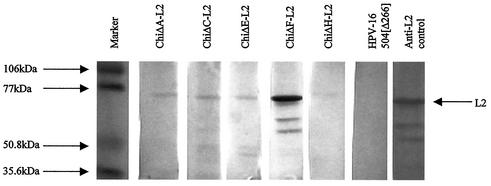

The chimeric constructs were successfully expressed in insect cells using recombinant baculoviruses and purified using CsCl gradient centrifugation. Fractions were analyzed by ELISA using H16:J4 MAb, since the epitope that binds this MAb was not altered in any construct. Positive fractions were pooled and dialyzed for further analysis. The sizes of the chimeric L1-L2 protein products, predicted as 55 kDa, were confirmed by Western blot analysis using H16:J4 MAb (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of chimeric products using H16:J4 MAb. This MAb binds a linear epitope in the region aa 261 to 280. A 55-kDa product was detected for all the chimeras, similar to that of native HPV-16 L1.

Transmission electron microscopy of chimeric particles.

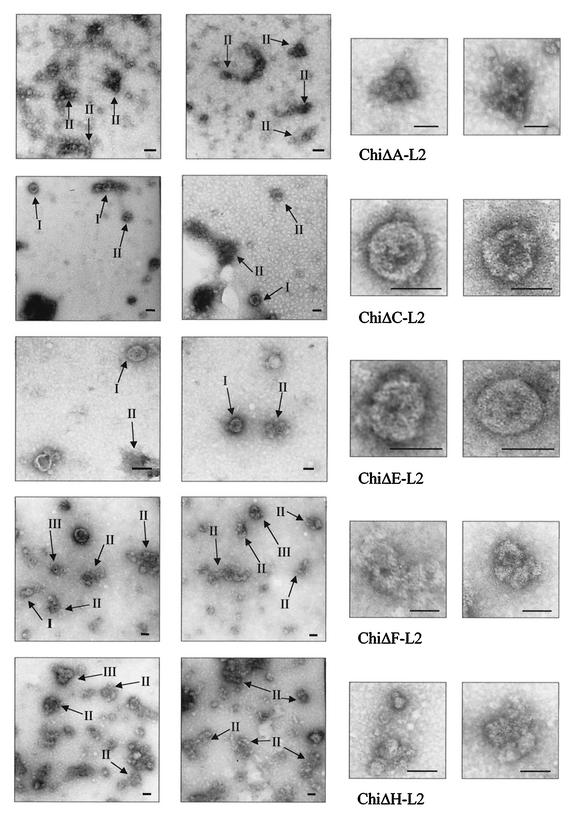

Chimeric particles from ChiΔC-L2 and ChiΔE-L2 formed recognizable VLPs and capsomers, whereas the rest of the chimeras apparently only formed capsomers and amorphous aggregates (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

EM of chimeric particles trapped with MAb H16:J4 onto carbon-coated copper grids and negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate (bar = 50 nm). Enlargements on the right show individual particles for ChiΔC-L2 and ChiΔE-L2, VLPs in state of disassembly for ChiΔF-L2, and pentameric aggregates for ChiΔA-L2 and ChiΔH-L2.

Antibody characterization of the chimeric L1 protein products using a panel of MAbs.

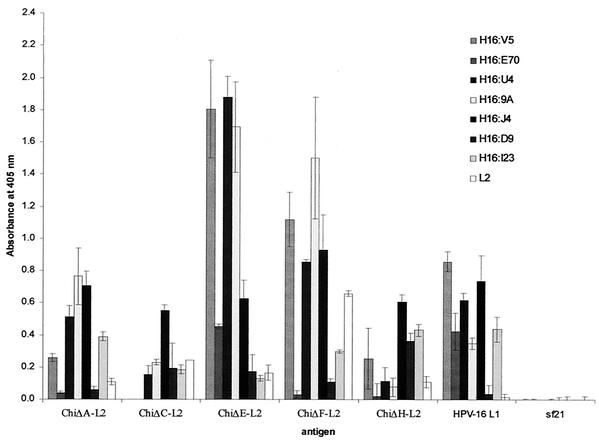

The ELISA binding results for purified chimeric proteins with a panel of characterized MAbs (6, 7,30, 41) are summarized in Fig. 3. The antigen concentrations were normalized using MAb H16:J4 prior to antibody characterization: this MAb binds a linear epitope that was maintained in all the chimeras; thus, if one assumes that the MAb binds similarly to each antigen, the antigenicity data presented in Fig. 3 are relative to H16:J4 binding. All the chimeric particles and proteins bound the antibodies specific for the linear epitopes (H16:J4, aa 261 to 280; H16:D9, epitope unknown; and H16:I23, aa 111 to 130). All the conformationally dependent neutralizing MAbs (H16:V5, H16:E70, H16:U4, and H16:9A) reacted with particles of chimeras ChiΔA-L2, ChiΔE-L2, and ChiΔF-L2. Of the conformationally dependent MAbs, particles of chimera ChiΔC-L2 recognized only H16:U4 and H16:9A, indicating the disruption of the V5 and E70 neutralizing epitopes. Particles of ChiΔH-L2 showed very weak binding to conformation-dependent MAbs and strong binding to H16:D9, which predominantly binds denatured HPV-16 L1 VLPs (7). These data indicated that the protein aggregation products that resulted from ChiΔH-L2 were either unstable and/or misassembled.

FIG. 3.

Antibody-binding characterization of the purified chimeric product using a panel of MAbs raised to HPV-16 L1 VLPs and a polyclonal antibody raised to the L2 epitope. H16:V5 and H16:E70 are conformation-specific neutralizing MAbs, and residues Phe-50, Ala-266, and Ser-282 are critical for their binding (41). MAbs H16:U4 (binding epitope not characterized) and H16:9A (binds in the region aa 1 to 172) are both conformation-specific and neutralizing, whereas H16:J4 (binds between aa 261 to 280) and H16:I23 (binds between aa 111 and 130) are weakly neutralizing and recognize linear epitopes. H16:D9 has a high affinity for denatured L1.

The polyclonal antiserum raised in rabbits to the L2 epitope peptide (aa 108 to 120) bound all the chimeric particles, indicating that all the HPV-16 chimeras displayed the L2 epitope. ChiΔF-L2 had the highest binding affinity, indicating that the L2 epitope in the L1 sequence region from aa 414 to 426 is perhaps the most highly exposed of all the constructs.

Immunization of BALB/c mice with chimeric particles and analysis of immune sera.

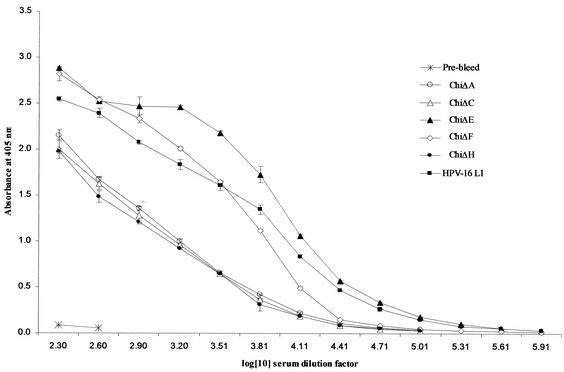

The results above indicated that four of the chimeras were capable of binding one or more conformation-specific neutralizing MAbs. It was important to determine if these particles could induce an HPV-16 L1 immune response and, secondly, if the L2 epitope displayed by the chimeras was immunogenic. Analysis of sera from mice immunized with the chimeric particles indicated that there was a strong immune response (titers ≥ 102,400) to HPV-16 L1 VLPs: end point titration data are shown in Fig. 4. Particles of ChiΔE-L2 induced the strongest immune response (Fig. 4), similar to that elicited with native HPV-16 L1 VLPs (titers ≥ 819,200), followed by ChiΔF-L2 (titers ≥ 204,800) and then ChiΔA-L2, ChiΔC-L2, and ChiΔH-L2, with similar end point titers (≥102,400). These data correlate well with our antibody characterization data (Fig. 3). It is interesting that the L1-specific immune response to ChiΔC-L2 is much lower than that to ChiΔE-L2, yet both of these assemble VLPs. We speculate that this is due to the structural alteration of the immunodominant region (V5 and E70 epitopes).

FIG. 4.

End point titrations of sera from BALB/c mice immunized with chimeric products against HPV-16 L1 VLPs.

The immune response to the linear L2 epitope was analyzed by Western blotting using the L2 protein expressed in E. coli. The strongest response was obtained from mice immunized with ChiΔF-L2 (Fig. 5). The C-terminal arm of the L1 is exposed on the surface of the HPV virion, near the outer rim of the pentamer, and is hence thought to be highly immunogenic. ChiΔC-L2 and ChiΔE-L2 constructs had a slightly higher L2 epitope response than ChiΔA-L2. This correlates well with L2 antibody binding, where ChiΔF-L2 had the highest affinity followed by ChiΔE-L2, ChiΔC-L2, and ChiΔA-L2 (Fig. 3). We were barely able to detect the L2 epitope immune response from ChiΔH-L2, suggesting that the L2 epitope was not well presented on this chimera.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of immune responses to L2 epitopes presented by various chimeras. The sera were analyzed against HPV-16 L2 protein expressed in E. coli.

DISCUSSION

The main goal of our study was to further investigate the potential of HPV-16 VLPs for delivery or presentation of foreign epitopes in a multivalent vaccine. With the data from the crystal structure study of truncated HPV-16 L1 (10-aa N-terminal deletion) (5) we were able to logically identify regions with potential for display of foreign epitopes. Kawana et al. (18) identified a region in the HPV-16 L2 minor capsid protein (aa 108 to 120) that was capable of reducing susceptibility of the COS-1 cells to HPV-16 pseudovirion infection (19). We chose to use this L2 epitope for incorporation into our putative multivalent vaccine candidates.

The main factor taken into account when considering putative regions to display the L2 epitope was the preservation of the MAb H16:V5 and MAb H16:E70 binding epitope (5, 30): White et al. (41) mapped the binding of these neutralizing MAbs on HPV-16 L1 VLPs to residues Phe-50, Ala-266, and Ser-282. The H16:V5 MAb has been shown to completely block the binding of 70% of human sera to HPV-16 virions (30); hence, the H16:V5 binding site is considered a major immunodominant epitope and is used as a marker for the efficacy of HPV-16 vaccines.

Chimera ChiΔA-L2.

The L2 epitope in ChiΔA-L2 is probably displayed on the outer rim of the pentamer, which putatively interacts with the C-terminal arms from neighboring pentamers. This interaction is perhaps lost in this construct, as the cysteine at residue 175 that forms a disulfide bond with residue 428 is replaced by a valine. Mutagenesis experiments performed by Fligge et al. (10), Li et al. (21) and Sapp et al. (33) have identified Cys-175 and Cys-428—both conserved among all PV types—as being likely to form disulfide bonds. The atomic structure model of HPV-16 L1 of Modis et al. (24) indicates that the Cys-175 forms a disulfide bond with the Cys-428 from an invading C-terminal arm. Therefore, the substitution of the cysteine to a valine at residue 175 could potentially interfere on the formation of the interpentameric disulfide bond, which could prevent assembly into VLPs. Based on these data we expected chimera ChiΔA-L2 to form only capsomers, which is what we observed (Fig. 2).

Chimera ChiΔC-L2.

ChiΔC-L2 the has potential of inducing a neutralizing L1 response since it binds the neutralizing H16:U4, H16:J4, H16:I23, and H16:9A MAbs, the last of which targets the N terminal region of HPV-16 L1 (6). In ChiΔC-L2, the L2 epitope is displayed on the head of the pentamer and residue Tyr-135 is replaced by Thr-135 which had direct interaction with residue Ser-282. We believe that the Tyr-135-Ser 282 interaction is critical for H16:V5 and H16:E70 MAb binding since is Ser-282 is one of the epitopes mapped for H16V5 and H16:E70 MAb binding. There might also be other important interactions that have been destroyed by substitution into the D-E loop which has major interactions with the F-G loop in HPV-16 L1 particles.

Chimera ChiΔE-L2 and chimera ChiΔF-L2.

The most immunogenic chimera overall was ChiΔF-L2, where the L2 epitope was presented in place of the h4 helix: this region (aa 414 to 426) is highly exposed in the atomic structure of HPV-16 L1 proposed by Modis et al. (24) and therefore probably highly immunogenic. Chimera ChiΔF-L2 bound all the neutralizing MAbs and induced a strong L1 and L2 epitope response. We suspect that the h4 helix in native VLPs forms important interactions and that altering this region prevents the formation of VLPs. Chen et al. (4) showed that deletion of the region aa 408 to 431 resulted in pentamer formation only; these observations support our finding that ChiΔF-L2 is only seen to form capsomers. Particles of ChiΔE-L2 would ideally be expected to be equally immunogenic in regard to the L2 epitope as ChiΔF-L2, but this is not the case. In the atomic structure of HPV-16 L1, residues 431 and 432 are less accessible due to the disulfide bond between Cys-175 and Cys-428, and the region between residues 433 and 443 is overall less accessible than the h4 helix region. Therefore ChiΔE-L2, even though it was capable of assembling into VLPs, induced a weak L2 response. Our antibody characterization data indicated that particles of ChiΔF-L2 had the highest binding affinity to the L2 epitope antibody (Fig. 3) and that these particles induced a strong L1 immune response (titers ≥ 204,800) in BALB/c mice, though this was lower than that of ChiΔE-L2 (≥819,200). The stronger L1 immune response induced by particles of ChiΔE-L2 could be attributed to the formation of VLPs, which are probably more immunogenic than capsomers.

Chimera ChiΔH-L2.

The low binding affinity of conformation-specific MAbs to particles of ChiΔH-L2 could be attributed to the alteration of the L1 structure by the substitution of the L2 epitope into the C-D loop. The C-D loop (residues 79 to 94) forms important contacts between subunits in pentavalent pentamers and adjacent subunits in hexavalent pentamers (24): the C-D loop from one pentamer interacts directly with the C-D loop from a neighboring pentamer in an opposing manner. The C-D loop is highly conserved among PV types; hence, we speculate that substitution of the L2 epitope in the C-D loop (ChiΔH-L2) could have potentially prevented the formation of VLPs. The EM results, which showed that the products of chimera ChiΔH-L2 are predominately capsomers, support the notion of a change in the conformation of the L1 tertiary structure.

EM of chimeric particles.

Electron microscopy (EM) of chimeric L1 protein aggregates purified by isopycnic CsCl gradient fractionation from recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells indicated that ChiΔC-L2 and ChiΔE-L2 appeared to retain the ability to assemble into recognizable VLPs as well as capsomers, while the other three only formed capsomers and irregular aggregates (Fig. 2). This indicates that substitutions of the L2 peptide sequence in the D-E loop, which is located on the pentamer head and C-terminal arm (region between the h4 helix and the β-J sheet), are better tolerated structurally than the other substitutions in terms of complete assembly but that none of the substitutions affected the first-stage pentameric capsomer assembly. Substitution in the D-E loop does not affect the gross structure, but only the region around the F-G loop; hence, the loss in binding to MAb H16:V5 and H16:E70. The EM results also indicate that the sequence in the C-D loop is critical for maintaining the integrity of PV particles. The destruction of the h4 helix might have resulted in a gross conformation change in the packing of the C-terminal arm from a neighboring subunit preventing VLP assembly.

In summary, we have successfully investigated the use of HPV-16 L1 to present the HPV-16 L2 epitope (LVEETSFIDAGAP) (18), which cross-neutralizes HPV-6 and -16 (16). Of all the chimeras tested we found chimera ChiΔF-L2 (substitution into the h4 helix region; aa 414 to 426) to be the most effective at both presenting the L2 epitope and maintaining the neutralizing MAb H16:V5 and H16:E70 binding. H16:V5 MAbs have been shown to block more than 70% of (HPV-16-infected) patient sera from binding HPV-16 pseudovirions (30), thus maintaining the V5 epitope is seen as critical for eliciting a neutralizing HPV-16 response.

Further, recent studies have shown that sera raised to two linear epitopes on HPV-16 were capable of neutralizing HPV-16, -18, -31, -33, -45, -55, and -59 (9). All of our chimeras bind MAbs raised against these two epitopes. Therefore, our investigation into the use of PV to display foreign epitopes opens avenues for the synthesis of novel multivalent vaccines, where the epitopes could be displayed in a variety of regions, and multiple epitopes could also potentially be displayed on the particle at different surface locations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an Innovation Fund grant (project 414224) from the South African Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST).

We thank Rodney Lucas and Marleze Rheeder for help with the animal work; John Schiller for providing the HPV-16 L2-E2-E7 clone; Juliet Hogg for preparing the HPV-16 L2 protein; and Trevor Sewell, Yorgo Modis, and Xiaojiang Chen for discussions about structure.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breitburd, F., J. Salmon, and G. Orth. 1997. Animal models for evaluation of human papillomavirus vaccines, p. 432-445. In E. L. Franco and J. Monsonego (ed.), New developments in cervical cancer screening and prevention. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom

- 2.Carter, J. J., L. A. Koutsky, J. P. Hughes, S. K. Lee, J. Kuypers, N. Kiviat, and D. A. Galloway. 2000. Comparison of human papillomavirus types 16, 18, and 6 capsid antibody responses following incident infection. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1911-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter, J. J., L. A. Koutsky, G. C. Wipf, N. D. Christensen, S. K. Lee, J. Kuypers, N. Kiviat, and D. A. Galloway. 1996. The natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 capsid antibodies among a cohort of university women. J. Infect. Dis. 174:927-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, X. S., G. Casini, S. C. Harrison, and R. L. Garcea. 2001. Papillomavirus capsid protein expression in Escherichia coli: purification and assembly of HPV11 and HPV16 L1. J. Mol. Biol. 307:173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, X. S., R. L. Garcea, I. Goldberg, G. Casini, and S. C. Harrison. 2000. Structure of small virus-like particles assembled from the L1 protein of human papillomavirus 16. Mol. Cell 5:557-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen, N. D., N. M. Cladel, C. A. Reed, L. R. Budgeon, M. E. Embers, D. M. Skulsky, W. L. McClements, S. W. Ludmerer, and K. U. Jansen. 2001. Hybrid papillomavirus L1 molecules assemble into virus-like particles that reconstitute conformational epitopes and induce neutralizing antibodies to distinct HPV types. Virology 291:324-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen, N. D., J. Dillner, C. Eklund, J. J. Carter, G. C. Wipf, C. A. Reed, N. M. Cladel, and D. A. Galloway. 1996. Surface conformational and linear epitopes on HPV-16 and HPV-18 L1 virus-like particles as defined by monoclonal antibodies. Virology 223:174-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen, N. D., C. A. Reed, N. M. Cladel, R. Han, and J. W. Kreider. 1996. Immunization with viruslike particles induces long-term protection of rabbits against challenge with cottontail rabbit papillomavirus. J. Virol. 70:960-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combita, A. L., A. Touze, L. Bousarghin, N. D. Christensen, and P. Coursaget. 2002. Identification of two cross-neutralizing linear epitopes within the L1 major capsid protein of human papillomaviruses. J. Virol. 76:6480-6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fligge, C., T. Giroglou, R. E. Streeck, and M. Sapp. 2001. Induction of type-specific neutralizing antibodies by capsomeres of human papillomavirus type 33. Virology 283:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenstone, H. L., J. D. Nieland, K. E. de Visser, M. L. De Bruijn, R. Kirnbauer, R. B. Roden, D. R. Lowy, W. M. Kast, and J. T. Schiller. 1998. Chimeric papillomavirus virus-like particles elicit antitumor immunity against the E7 oncoprotein in an HPV16 tumor model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1800-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harro, C. D., Y. Y. Pang, R. B. Roden, A. Hildesheim, Z. Wang, M. J. Reynolds, T. C. Mast, R. Robinson, B. R. Murphy, R. A. Karron, J. Dillner, J. T. Schiller, and D. R. Lowy. 2001. Safety and immunogenicity trial in adult volunteers of a human papillomavirus 16 L1 virus-like particle vaccine. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93:284-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansen, K. U., M. Rosolowsky, L. D. Schultz, H. Z. Markus, J. C. Cook, J. J. Donnelly, D. Martinez, R. W. Ellis, and A. R. Shaw. 1995. Vaccination with yeast-expressed cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) virus-like particles protects rabbits from CRPV-induced papilloma formation. Vaccine 13:1509-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins, O., J. Cason, K. L. Burke, D. Lunney, A. Gillen, D. Patel, D. J. McCance, and J. W. Almond. 1990. An antigen chimera of poliovirus induces antibodies against human papillomavirus type 16. J. Virol. 64:1201-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jochmus, I., K. Schafer, S. Faath, M. Muller, and L. Gissmann. 1999. Chimeric virus-like particles of the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV 16) as a prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine. Arch. Med. Res. 30:269-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawana, K., Y. Kawana, H. Yoshikawa, Y. Taketani, K. Yoshiike, and T. Kanda. 2001. Nasal immunization of mice with peptide having a cross-neutralization epitope on minor capsid protein L2 of human papillomavirus type 16 elicit systemic and mucosal antibodies. Vaccine 19:1496-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawana, K., K. Matsumoto, H. Yoshikawa, Y. Taketani, T. Kawana, K. Yoshiike, and T. Kanda. 1998. A surface immunodeterminant of human papillomavirus type 16 minor capsid protein L2. Virology 245:353-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawana, K., H. Yoshikawa, Y. Taketani, K. Yoshiike, and T. Kanda. 1999. Common neutralization epitope in minor capsid protein L2 of human papillomavirus types 16 and 6. J. Virol. 73:6188-6190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawana, Y., K. Kawana, H. Yoshikawa, Y. Taketani, K. Yoshiike, and T. Kanda. 2001. Human papillomavirus type 16 minor capsid protein l2 N-terminal region containing a common neutralization epitope binds to the cell surface and enters the cytoplasm. J. Virol. 75:2331-2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirnbauer, R., N. L. Hubbert, C. M. Wheeler, T. M. Becker, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 1994. A virus-like particle enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum antibodies in a majority of women infected with human papillomavirus type 16. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 86:494-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, M., D. L. Beck, P. A. Estes, M. K. Lyon, and R. L. Garcea. 1998. Intercapsomeric disulfide bonds in papillomavirus assembly and disassembly. J. Virol. 72:2160-2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, W. J., X. S. Liu, K. N. Zhao, G. R. Leggatt, and I. H. Frazer. 2000. Papillomavirus virus-like particles for the delivery of multiple cytotoxic T cell epitopes. Virology 273:374-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, X. S., W. J. Liu, K. N. Zhao, Y. H. Liu, G. Leggatt, and I. H. Frazer. 2002. Route of administration of chimeric BPV1 VLP determines the character of the induced immune responses. Immunol. Cell Biol. 80:21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Modis, Y., B. L. Trus, and S. C. Harrison. 2002. Atomic model of the papillomavirus capsid. EMBO J. 21:4754-4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller, M., J. Zhou, T. D. Reed, C. Rittmuller, A. Burger, J. Gabelsberger, J. Braspenning, and L. Gissmann. 1997. Chimeric papillomavirus-like particles. Virology 234:93-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netter, H. J., T. B. Macnaughton, W. P. Woo, R. Tindle, and E. J. Gowans. 2001. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of novel chimeric hepatitis B surface antigen particles with exposed hepatitis C virus epitopes. J. Virol. 75:2130-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieland, J. D., D. M. Da Silva, M. P. Velders, K. E. de Visser, J. T. Schiller, M. Muller, and W. M. Kast. 1999. Chimeric papillomavirus virus-like particles induce a murine self-antigen-specific protective and therapeutic antitumor immune response. J. Cell Biochem. 73:145-152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niikura, M., S. Takamura, G. Kim, S. Kawai, M. Saijo, S. Morikawa, I. Kurane, T. C. Li, N. Takeda, and Y. Yasutomi. 2002. Chimeric recombinant hepatitis E virus-like particles as an oral vaccine vehicle presenting foreign epitopes. Virology 293:273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pastrana, D. V., W. C. Vass, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. 2001. NHPV16 VLP vaccine induces human antibodies that neutralize divergent variants of HPV16. Virology 279:361-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roden, R. B., A. Armstrong, P. Haderer, N. D. Christensen, N. L. Hubbert, D. R. Lowy, J. T. Schiller, and R. Kirnbauer. 1997. Characterization of a human papillomavirus type 16 variant-dependent neutralizing epitope. J. Virol. 71:6247-6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose, R. C., W. I. White, M. Li, J. A. Suzich, C. Lane, and R. L. Garcea. 1998. Human papillomavirus type 11 recombinant L1 capsomeres induce virus-neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 72:6151-6154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy, P. 1996. Genetically engineered particulate virus-like structures and their use as vaccine delivery systems. Intervirology 39:62-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapp, M., C. Fligge, I. Petzak, R. Harris, and R. E. Streeck. 1998. Papillomavirus assembly requires trimerization of the major capsid protein by disulfides between two highly concerned cysteines. J. Virol. 72:6186-6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schafer, K., M. Muller, S. Faath, A. Henn, W. Osen, H. Zentgraf, A. Benner, L. Gissmann, and I. Jochmus. 1999. Immune response to human papillomavirus 16 L1E7 chimeric virus-like particles: induction of cytotoxic T cells and specific tumor protection. Int. J. Cancer 81:881-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiller, J. T., and D. R. Lowy. 2001. Papillomavirus-like particle based vaccines: cervical cancer and beyond. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 1:571-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seedorf, K., G. Krammer, M. Durst, S. Suhai, and W. G. Rowekamp. 1985. Human papillomavirus type 16 DNA sequence. Virology 145:181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slupetzky, K., S. Shafti-Keramat, P. Lenz, S. Brandt, A. Grassauer, M. Sara, and R. Kirnbauer. 2001. Chimeric papillomavirus-like particles expressing a foreign epitope on capsid surface loops. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2799-2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanley, M. A., R. A. Moore, P. K. Nicholls, E. B. Santos, L. Thomsen, N. Parry, S. Walcott, and G. Gough. 2001. Intra-epithelial vaccination with COPV L1 DNA by particle-mediated DNA delivery protects against mucosal challenge with infectious COPV in beagle dogs. Vaccine 19:2783-2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzich, J. A., S. J. Ghim, F. J. Palmer-Hill, W. I. White, J. K. Tamura, J. A. Bell, J. A. Newsome, A. B. Jenson, and R. Schlegel. 1995. Systemic immunization with papillomavirus L1 protein completely prevents the development of viral mucosal papillomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11553-11557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, Z., N. Christensen, J. T. Schiller, and J. Dillner. 1997. A monoclonal antibody against intact human papillomavirus type 16 capsids blocks the serological reactivity of most human sera. J. Gen. Virol. 78:2209-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White, W. I., S. D. Wilson, F. J. Palmer-Hill, R. M. Woods, S.-J. Ghim, L. A. Hewitt, D. M. Goldman, S. J. Burke, A. B. Jenson, S. Koenig, and J. A. Suzich. 1999. Characterization of major neutralizing epitope on human papillomavirus type 16 L1. J. Virol. 73:4882-4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan, H., P. A. Estes, Y. Chen, J. Newsome, V. A. Olcese, R. L. Garcea, and R. Schlegel. 2001. Immunization with a pentameric L1 fusion protein protects against papillomavirus infection. J. Virol. 75:7848-7853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, L. F., J. Zhou, S. Chen, L. L. Cai, Q. Y. Bao, F. Y. Zheng, J. Q. Lu, J. Padmanabha, K. Hengst, K. Malcolm, and I. H. Frazer. 2000. HPV6b virus like particles are potent immunogens without adjuvant in man. Vaccine 18:1051-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.zur Hausen, H. 1996. Papillomavirus infections—a major cause of human cancers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1288:F55-F78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]