Abstract

The role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDC), the major producers of alpha interferon upon viral infection, in the nasal mucosa is largely unknown. Here we examined the presence of PDC together with myeloid dendritic cells (MDC) in the nasal epithelia of healthy individuals, of asymptomatic patients with chronic nasal allergy, of patients undergoing steroid therapy, and of patients with infectious rhinitis or rhinosinusitis. Considerable numbers of PDC and MDC could be detected in the nasal epithelium. Furthermore, we demonstrate the expression of SDF-1, the major chemoattractant for PDC, in the nasal epithelium. PDC levels were significantly lower for patients with allergies than for healthy individuals. Interestingly, PDC and MDC were almost absent from patients who received treatment with glucocorticoids, while very high numbers of PDC were found for patients with recent upper respiratory tract infections. Our results demonstrate for the first time a quantitative analysis of PDC and MDC in the healthy nasal epithelium and in nasal epithelia from patients with different pathological conditions. With the identification of PDC, the major target cell for CpG DNA or immunostimulatory RNA, in the nasal epithelium, this study forms the basis for a local nasal application of such oligonucleotides for the treatment of viral infection and allergy.

The nasal mucosa is a part of the outer mucosal barrier and fulfills a number of key functions, such as humidifying, filtering, and warming the air. The nasal turbinates project from the lateral wall of the nose and increase the interior surface area of the nose. This large surface not only serves specific functions but also provides a large entry site for airborne particles, toxic agents, proteins, and invading pathogens such as viruses and bacteria. The immune response of the mucosa strongly depends on the presence of different infiltrating immune cells. Antigen-presenting cells (APC) in general play a major role in directing an adequate immune response. In contrast to other antigen-presenting cells, such as monocytes, macrophages, and B cells, dendritic cells have as their main feature the presentation of antigens and the initiation of the priming of naive CD4 and CD8 T cells to a specific antigen (45).

In the literature, APC subpopulations in healthy upper airway mucosa have often been evaluated based on typical dendritic cell-like morphology by use of immunohistochemistry on paraffin-embedded or frozen tissue sections (18, 20, 30). Such cells with dendritic cell-like morphology often stain positive for CD1a and therefore have been termed Langerhans cells (LC). However, in contrast to what is seen for skin, the identity of Langerhans cells in upper airway mucosa is not well defined, since CD1a is expressed only on a subset of CD11c-positive myeloid dendritic cells and since CD1a is also present on activated macrophages (30).

In peripheral blood, two major subsets of dendritic cells, myeloid dendritic cells (MDC) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDC), have been identified (41). PDC and MDC each represent about 0.2 to 0.4% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in peripheral blood (35). Both subsets are characterized by the lack of lineage markers and the expression of CD4. Whereas CD11c is expressed on MDC, the expression of CD123 and of the PDC-specific antigen BDCA-2 and a plasma cell-like morphology are characteristic of PDC (38). As the nasal epithelium represents the first entry site for viruses, excellent defense mechanisms need to be in place to protect the nasal epithelium from viral infection. Along with the adaptive immune system, the innate immune system provides protection against invading virus. The key cell type for detection and defense against viruses is the PDC.

In humans, PDC have been found in the peripheral blood (5, 48), in the tonsils (49), in the cerebrospinal fluid (43), and in the nasal mucosa of allergic subjects after topical allergen challenge (31) and are associated with pathological conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (15), head and neck squamous cell cancer (21), malignant ascites of patients with ovarian carcinomas (55), and inflammatory skin diseases (54). The specific feature of PDC is the production of large amounts of alpha interferon (IFN-α) in response to viral infection. Upon activation with virus, PDC are strongly activated, resulting in production of large amounts of type I interferon, and are therefore also called natural type I IFN-producing cells (1, 6, 17). IFN-α is one of the most potent antiviral cytokines.

PDC recognize CpG motifs within microbial DNA; synthetic oligonucleotides containing such CpG motifs are used to mimic microbial DNA (4, 23, 34). CpG motifs are unmethylated CG dinucleotides within certain sequence contexts. The vertebrate immune system is able to detect pathogen-specific molecules via the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family (50). So far, only two cell types in the human immune system which are capable of detecting CpG motifs based on the expression of TLR9 have been identified: B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (29, 35). Based on the ability to stimulate IFN-α production in PDC, three distinct classes of CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), namely, CpG-A (high IFN-α production in PDC), CpG-B (low induction of IFN-α but strong B-cell stimulation), and CpG-C (high induction of IFN-α and strong B-cell stimulation) (22, 33, 34), have been identified.

TLR expression in PDC is limited to TLR7 and TLR9 (25, 29, 35). TLR7 and TLR9 are both located in endosomal membranes. Recently, it was shown that TLR7 detects not only single-stranded RNA of single-stranded RNA viruses (11, 24) but also short double-stranded RNA with certain sequence motifs (immunostimulatory RNA [isRNA]) (29). Therefore, synthetic isRNA sequences and synthetic CpG oligonucleotides can be used to trigger either TLR7 or TLR9.

When recognizing virus, CpG DNA, or isRNA, PDC are strongly activated, resulting in the production of large amounts of type I interferon (5, 28, 34) and the initiation of an adequate immune response. The presence of even small numbers of PDC potently modulates the activity of other immune cell subsets, such as T cells, NK cells, and myeloid dendritic cells (32, 35, 46). In order to use immunostimulatory oligonucleotides for prophylaxis and treatment of viral rhinitis, the target PDC needs to be in place.

Our results for the first time show a quantitative flow cytometric analysis of PDC and MDC in the healthy human nasal epithelium and in nasal epithelia from patients with different pathological conditions. We demonstrate that relatively high numbers of PDC and MDC reside in the healthy nasal epithelium. Furthermore, we made the surprising observation that PDC levels are suppressed in asymptomatic patients with chronic nasal allergy, while they are high during infectious inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human tissue samples and patient characteristics.

Inferior nasal turbinates of patients undergoing nasal surgery were obtained during a standard surgical procedure, septoplasty including conchotomy. Tissue sizes ranged from 0.4 to 1.1 cm in width and from 1.5 to 3.0 cm in length. Tissue specimens were transported in sterile saline and processed immediately after excision. The characteristics of patients are provided in Table 1. Lymphoid tissue was obtained from pharyngeal tonsils from children undergoing adenotomy. The use of human materials for research purposes was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Munich.

TABLE 1.

Clinical data and frequencies of PDC and MDC in nasal mucosae of patients with or without allergy, treatment with corticosteroid medication, and/or current infection of the upper airwaya

| Group | Patient | Patient characteristicb

|

Frequency (%) of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | Allergy | Steroids | Infection | PDC | MDC | ||

| 1 | 3 | 44 | − | − | − | 0.9 | ND |

| 9 | 63 | − | − | − | 1.1 | 0.4 | |

| 13 | 35 | − | − | − | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 14 | 37 | − | − | − | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 16 | 18 | − | − | − | 0.6 | 0.9 | |

| 19 | 45 | − | − | − | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| 25 | 66 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.4 | |

| 27 | 21 | − | − | − | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| 29 | 41 | − | − | − | 0.1 | ND | |

| 30 | 40 | − | − | − | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| 37 | 54 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.4 | |

| 40 | 43 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 41 | 42 | − | − | − | 0.6 | 0.6 | |

| 42 | 55 | − | − | − | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| 43 | 39 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.5 | |

| 45 | 42 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 46 | 35 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 47 | 67 | − | − | − | 0.1 | 0.0 | |

| 49 | 38 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 56 | 38 | − | − | − | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| 57 | 26 | − | − | − | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 58 | 44 | − | − | − | 0.3 | 0.8 | |

| 63 | 61 | − | − | − | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| 2 | 2 | 20 | + | − | − | 0.0 | ND |

| 8 | 64 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| 10 | 47 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.1 | ND | |

| 11 | 20 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| 17 | 40 | + (perennial) | − | − | 0.0 | 0.2 | |

| 18 | 33 | + | − | − | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| 20 | 36 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| 21 | 61 | + (perennial) | − | − | 0.0 | 0.3 | |

| 22 | 13 | + (perennial) | − | − | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 31 | 37 | + (seasonal 1) | − | − | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 33 | 25 | + | − | − | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| 34 | 45 | + | − | − | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 38 | 17 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| 39 | 44 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| 44 | 37 | + (seasonal 1) | − | − | 0.1 | 0.4 | |

| 50 | 35 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 54 | 20 | + (perennial) | − | − | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 55 | 43 | + (perennial) | − | − | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 65 | 22 | + (seasonal) | − | − | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| 3 | 4 | 38 | + (insect venom) | + | − | 0.0 | ND |

| 5 | 23 | − | + | − | 0.0 | ND | |

| 6 | 27 | − | + | − | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| 23 | 25 | − | + | − | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| 32 | 55 | − | + | − | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| 36 | 24 | − | + | − | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| 48 | 45 | − | + | − | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 53 | 49 | − | + | − | 0.1 | 0.0 | |

| 61 | 33 | + (seasonal) | + | − | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| 62 | 41 | − | + | − | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| 64 | 24 | − | + | − | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| 66 | 18 | − | + | − | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 4 | 24 | 23 | − | − | + | 2.2 | 1.4 |

| 28 | 28 | + (seasonal) | − | + | 0.5 | 1.6 | |

| 35 | 69 | ND | + | + | 0.9 | 0.3 | |

| 51 | 63 | − | − | + | 1.2 | 1.7 | |

| 52 | 35 | − | − | + | 4.2 | 2.9 | |

| 59 | 31 | − | − | + | 1.5 | 1.3 | |

| 60 | 41 | − | − | + | 2.0 | 1.3 | |

| 67 | 37 | − | − | + | 1.2 | 1.0 | |

ND, not determined.

The presence of allergy, use of corticosteroid medication, and/or current infection of the upper airway is indicated. Seasonal 1, one specific seasonal allergy.

Preparation of single-cell suspensions and cell lines.

Nasal turbinates were washed several times and digested with dispase type I (0.78 U/mg; Gibco) for 45 min at 37°C in sterile serum-free RPMI medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 1 mmol/liter glutamine, and 100 U/ml streptomycin). Then, the epithelium was physically separated from the connective tissue by gentle scraping with a scalpel.

Nasopharyngeal tonsillar tissue was dissociated by passing it through a 100-μm nylon cell strainer with a syringe. The resulting cell suspensions were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in PBS containing trypsin-EDTA, and filtered through a 40-μm nylon cell strainer (Falcon; Becton Dickinson Labware) into cold RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Three cell lines were used: the human lung fibroblast cell line W138 (a gift from Olivier Gires, Munich, Germany) and two cell lines from head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, FADU and PCI-1 (a gift from Theresa Whiteside, Pittsburgh, Pa.).

Flow cytometry.

Surface antigen staining was performed as described previously (23). Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-, phycoerythrin-, peridinin-chlorophyll-protein-, or APC-conjugated antibodies by incubation on ice for 15 min followed by washing with PBS. Fluorescence-labeled monoclonal antibodies against CD1a, CD3, CD11c, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD56, CD80, CD86, CD123, and HLA-DR were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Heidelberg, Germany). Anti-BDCA-2 and anti-BDCA-4 were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany. Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson) by use of To-Pro-3 iodide (2 nM; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) to exclude dead cells. For analysis of CD86 expression on DC, CD86 instead of To-Pro was used. Dead cells in that staining procedure were excluded by morphology. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Cell Quest software.

Immunohistochemistry.

For immunohistochemical staining, tissue specimens were embedded in the Tissue-Tek microtome (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), cryopreserved in N2, and stored at −20°C. Acetone-fixed cryosections (4 μm) were incubated with the PDC-specific antibody BDCA-2 (14) for 1 h at room temperature after the blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity with 0.3% H2O2. The isotype antibody (mouse anti-human immunoglobulin G [IgG]; Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) was used as a negative control. After incubation with biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (1/300; Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) for 1 h at room temperature, sections were rinsed and incubated with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (1/200; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 30 min at room temperature. The chromogen 0.01% 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazol in 0.1 M Na-acetate buffer (0.0015% H2O2, 6% dimethyl sulfoxide, pH 5.5) was used. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells were stained in red. Mayer's hemalaun was used to counterstain cellular elements (blue). Double immunostaining was performed with mouse anti-human CD123 antibody [IgG2a(κ); Pharmingen] using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase method (red staining) as described above and with mouse anti-human HLA-DR antibody (IgG1κ; Dako) by use of the alkaline phosphatase-anti-alkaline phosphatase method (blue staining). The antigen-antibody complex was visualized using secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG) and subsequently incubated with alkaline phosphatase-anti-alkaline phosphatase complex (8) with commercial kits (Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark). As a chromogen we used fast blue (Sigma Chemicals).

Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR.

Cells were lysed, and RNA was extracted using a total RNA isolation kit (High Pure; RAS, Mannheim, Germany). An aliquot of 8.2 μl RNA was reverse transcribed using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT) as the primer (First Strand cDNA synthesis kit; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The obtained cDNA was diluted 1:25 with water, and 10 μl was used for amplification. Parameter-specific primer sets optimized for the LightCycler instrument (RAS, Mannheim, Germany) that were developed by Search-LC GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany) were purchased from Search-LC. The PCR was performed with the LightCycler FastStart DNA SYBR green kit (RAS) according to the protocol provided in the parameter-specific kits and as described previously (29). The copy number was calculated from a standard curve, which was obtained by plotting the known input concentrations of four different plasmids at log dilutions versus the PCR cycle number (cyclophilin B [CP]) at which the detected fluorescence intensity reaches a fixed value. By use of more than 300 data points, the actual copy number was calculated as follows: x = e(−0.6553 · CP + 20.62).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) or as box diagrams. Statistical significance of differences was determined by the paired two-tailed Student t test. The Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was performed. Statistical analyses were performed using StatView 4.51 software (Abacus Concepts Inc., Calabasas, CA).

RESULTS

Identification of PDC in healthy human nasal epithelium.

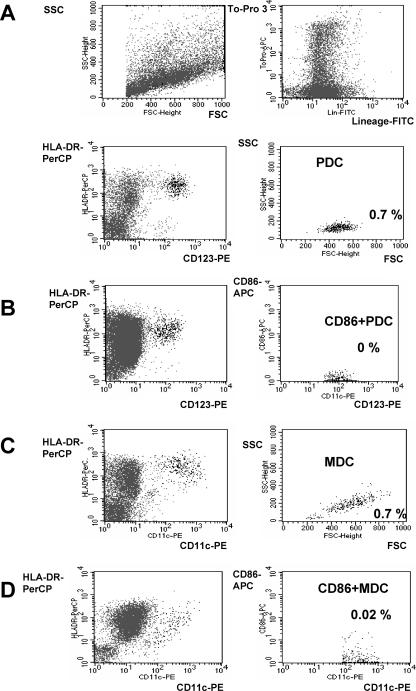

PDC have been identified in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (tonsils) and in nasal mucosa of patients with experimentally induced allergic rhinitis (31, 49). We hypothesized that PDC also reside in the healthy nasal epithelium. In peripheral blood, PDC can be identified by three-color staining and flow cytometry (lineage negative, major histocompatibility complex class II [MHC-II] positive, and CD123 positive) (48). MDC are stained by the same protocol but by applying CD11c instead of CD123. In order to examine the presence of PDC and MDC in the nasal epithelium, single-cell suspensions of the epithelial layer of conchotomy specimens were prepared and stained with a cocktail of lineage antibodies (CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, and CD56) and with MHC-II and CD123 or CD11c. Dead cells were excluded from analysis by positive staining for To-Pro. This procedure revealed a distinct population of cells with the typical characteristics of PDC (lineage negative, MHC-II positive, CD123 positive, and forward-scatter [FSC] and side-scatter [SSC] properties) or MDC (lineage negative, MHC-II positive, CD11c positive, and FSC and SSC properties). Both PDC (Fig. 1A) and MDC (Fig. 1B) were found in the epithelium of inferior nasal turbinates. PDC and MDC showed the same FSC and SSC properties as observed in tonsils, confirming the identity of these cell subsets. To determine activation, the upregulation of the costimulatory molecule CD86 was examined for selected individuals. CD86 expression could not be tested for all patients due to low cell numbers for most specimens studied. No CD86 expression was found in PDC or MDC of nasal epithelia from healthy individuals (Fig. 1A and B, lower panels).

FIG. 1.

Identification of plasmacytoid dendritic cells and myeloid dendritic cells in human nasal epithelium. A single-cell suspension from freshly resected human inferior nasal turbinates of a healthy individual (patient 19; Table 1) was prepared. Dead cells were excluded by To-Pro staining. (A and B) CD123-positive PDC were identified among lineage-negative HLA-DR-positive cells. The activation of PDC was analyzed by staining with CD86 by use of a different staining protocol (CD86 instead of To-Pro). (C and D) MDC were identified among lineage-negative and HLA-DR-positive cells by positive staining for CD11c. The activation of MDC was analyzed by expression of CD86. Numbers indicate the frequencies of PDC and MDC (%) within all cells of the single-cell suspension. Results for CD86 expression are representative of four independent experiments. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

Chemokine expression in nasal epithelium.

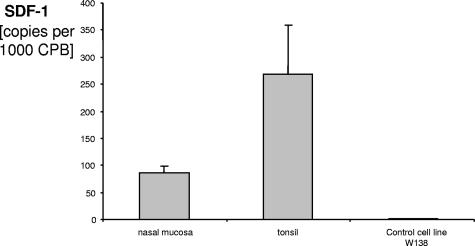

It has been reported that SDF-1 is responsible for the migration of PDC that are known to express the corresponding chemokine receptor, CXCR4 (36). Since we found that PDC are present in the healthy nasal epithelium, we hypothesized that SDF-1 is expressed in the nasal epithelium. The mRNA levels of SDF-1 in the nasal epithelium, in tonsillar tissue, and in three control cell lines (cell lines W138, FADU, and PCI) were analyzed. We found that SDF-1 copy numbers were highest in tonsillar tissue but that SDF-1 was also expressed at high numbers in nasal epithelium, although not in the control cell line W138 (Fig. 2). Two other control cell lines were also negative for SDF-1 (FADU and PCI; data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Real-time PCR analysis of SDF-1 mRNA expression in nasal epithelium and control tissue. The cDNA was prepared from nasal mucosae of patients undergoing nasal surgery (n = 8), from the cell line W138 (American Type Culture Collection) (pooled RNA), and from lymphatic tissue as the control (four tonsils). The level of SDF-1 mRNA was measured by quantitative real-time PCR. The mean copy numbers are indicated. Data are shown as means ± SEM. CPB, cyclophilin B.

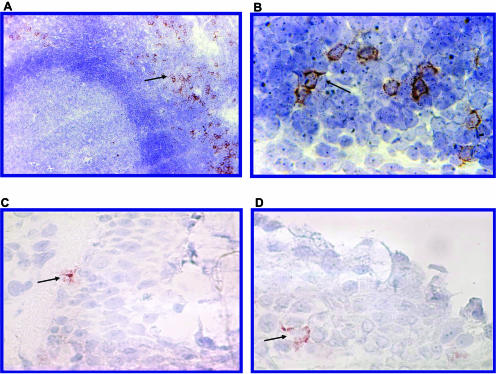

Localization of PDC in nasal epithelium and lymphoid tissue.

While CD123 in tissues is expressed not only in PDC but also in endothelial cells, the antibody against BDCA-2 has been described to specifically stain PDC (13, 14). In peripheral blood cells, BDCA-2 could be used instead of CD123 in the three-color staining protocol to identify PDC (data not shown). BDCA-4, another antibody which specifically stains PDC in peripheral blood (13), was less specific for PDC when used in the nasal mucosa (data not shown).

Therefore, we applied BDCA-2 to specifically stain PDC in cryosections of nasopharyngeal tonsils and nasal mucosae. Confirming earlier results (42, 49) for tonsils, PDC were found to be located in the perifollicular T-cell areas near high endothelial venules (Fig. 3A). In contrast, single staining with CD123 could not be used to specifically identify PDC in pharyngeal tonsils, since along with PDC, high endothelial venules also stained positive for CD123 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Localization of PDC in lymphatic tissue and in nasal epithelium. Sections of frozen tissue were stained with the PDC-specific antibody BDCA-2 (see Materials and Methods). (A and B) In tonsils, PDC are located around high endothelial venules in perifollicular T-cell areas (PDC indicated by arrows). (C and D) In the nasal mucosa, PDC (arrows) can be identified in the epithelial layer. Two representative sections of nasal epithelium are shown.

BDCA-2 staining of frozen sections of nasal epithelia revealed that PDC were located epithelially but also near blood vessels (Fig. 3B). Consistent with flow cytometric analysis, no PDC were found in skin biopsy specimens stained with BDCA-2 (data not shown).

Quantitative analysis of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in nasal epithelium.

After the identification of PDC in the nasal epithelium by flow cytometry and the confirmation of the presence of PDC in the nasal epithelium by immunohistochemistry, we were interested in quantifying PDC numbers for a wide range of individuals and comparing them to MDC numbers. Therefore, the frequencies of PDC and MDC were determined for single-cell suspensions of the epithelial layer of freshly resected inferior nasal turbinates obtained from 25 individual patients irrespective of their underlying disease. Although in the nasal epithelia the mean frequencies of PDC and MDC in these patients were similar (PDC, 0.45%; MDC, 0.48%), we observed a considerable variability in PDC (range, 0.01 to 2.2%) and MDC (range, 0.05 to 1.6%) numbers. In nasopharyngeal tonsils, the frequency of PDC was significantly higher than the frequency of MDC (PDC, 0.8%; MDC, 0.4%; n = 8; P = 0.009) (Fig. 4). Single-cell suspensions of human skin did not contain PDC or MDC but did contain CD1a-positive Langerhans cells (data not shown). Due to the differing cellular compositions of nasal epithelia and nasopharyngeal tonsils, the relative percentages of dendritic cell subsets between both tissues cannot be directly compared.

FIG. 4.

Quantitative analysis of PDC and MDC in nasal epithelium and nasopharyngeal tonsils. Single-cell suspensions of freshly resected inferior nasal turbinates (irrespective of underlying disease; patients 1 through 30 in Table 1) and of human nasopharyngeal tonsils were prepared. Within To-Pro-3- and lineage-negative cells, PDC were identified by positive staining for HLA-DR and CD123, and MDC were identified by positive staining for HLA-DR and CD11c. The frequencies of PDC and MDC within all cells of individual single-cell suspensions are depicted for nasal epithelia (n = 25) and pharyngeal tonsils (n = 8) (means ± SEM are indicated).

Different numbers of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in nasal epithelia of healthy individuals and of patients with allergy, with infection, and receiving steroid medication.

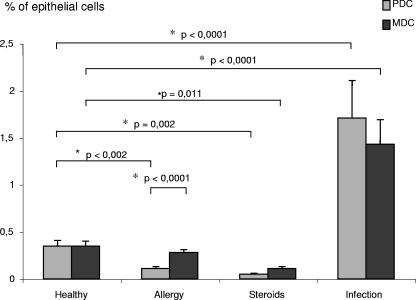

In the first series of analyses, we observed a wide range of PDC numbers (Fig. 4; patients 1 to 30 in Table 1). Since in this first group nasal inferior turbinates from healthy individuals and from patients were not examined separately, we speculated that the number of PDC in the nasal epithelium may depend on different pathological conditions. A retrospective analysis of this group pointed to higher PDC numbers for patients with infection. For an exact comparison of PDC numbers associated with different pathological conditions, a larger number of patients (patients 1 to 67; Table 1) were included. Patients undergoing nasal surgery fell into four groups. Group 1 (n = 23) comprised patients with deviation of the nasal septum or trauma without any other pathologies such as allergy or chronic infection. Group 2 (n = 19) represented patients with nasal allergy; allergy was defined by a positive skin prick test, increased titers of IgE in peripheral blood, and tryptase in nasal discharge and is defined as either seasonal allergy, such as pollen allergy (grass pollen, tree pollen), or perennial allergy (house dust mites, animals). Data were acquired postseasonally without reference to acute allergic inflammation status. Group 3 (n = 12) consisted of patients using systemic (n = 5) or topical (n = 7) steroid medication for the treatment of asthma or nasal polyposis. Group 4 (n = 8) consisted of patients undergoing routine surgery despite the presence of acute rhinitis or acute rhinosinusitis. For these four groups, PDC and MDC numbers in nasal epithelia were quantified by flow cytometry (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Frequencies of PDC and MDC under different pathological conditions. The frequencies of PDC and MDC were analyzed for four different groups of patients (patients 1 through 67; Table 1). Group 1 (n = 23) represents healthy patients with deviation of the nasal septum or trauma without other pathological conditions. Group 2 (n = 19) comprises asymptomatic patients with chronic nasal allergy. Group 3 (n = 12) represents patients using systemic or topic steroid medication. Group 4 (n = 8) represents patients with acute rhinitis or acute rhinosinusitis. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test and the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

In nasal epithelia of patients with perennial or seasonal allergies (group 2), the numbers of PDC were found to be significantly lower than those for healthy individuals in group 1 (0.11% ± 0.02% versus 0.35% ± 0.06%; P < 0.001); furthermore, in these patients, PDC numbers were significantly lower than MDC numbers, and MDC numbers were not decreased (0.28% ± 0.03% versus 0.35% ± 0.05% MDC). The use of steroids significantly diminished the numbers of both PDC and MDC in nasal epithelia (for group 3 versus group 1, the values for PDC were 0.05% ± 0.01% versus 0.35 ± 0.06% [P < 0.001], and those for MDC were 0.11% ± 0.02% versus 0.35% ± 0.05% [P < 0.005]). Patients with infection showed significantly higher numbers of PDC and of MDC (for group 4 versus group 1, the values for PDC were 1.71% ± 0.40% versus 0.35% ± 0.06% [P < 0.0001], and those for MDC were 1.43% ± 0.26% versus 0.35% ± 0.05% [P < 0.0001]).

The mean frequencies of PDC and MDC for all 61 patients were similar (PDC, 0.39%; MDC, 0.44%), with a considerable variability in PDC (range, 0.00 to 4.15%) and MDC (range, 0.00 to 2.9%) numbers.

DISCUSSION

Skin and mucosa are the two major surfaces of the body. In skin, the solid layer of keratinocytes represents a robust barrier against invading viruses. Consequently, PDC specialized for antiviral defense are absent in healthy skin and infiltrate skin only in the course of an inflammatory response (54). The situation is different for the second major surface, the mucosa. Mucosa has to fulfill a dual function: the exchange of molecules between the inside and the outside, and simultaneous protection against invading microbes. Since the first task does not allow the use of a solid keratinocyte layer for protection, we hypothesized that mucosa must exploit other ways of protecting against viruses. Among all mucosal surfaces, the nasal mucosa is the most exposed to frequent viral invaders in the upper respiratory tract. In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that remarkably high numbers of PDC, the immune cell subset specialized for detecting and defending against viruses, are present in the epithelial layer of the healthy nasal mucosa. Consistent with PDC infiltrating the healthy nasal epithelium, the strongest chemoattractant for PDC, SDF-1, was found to be expressed in the nasal epithelium. Quantitative analysis revealed similar numbers of MDC and PDC in nasal epithelia of healthy individuals. Considering the fraction of connective tissue cells, epithelial cells, and other nonimmune cells in nasal epithelial single-cell suspensions, PDC and MDC showed relatively high frequencies in nasal epithelium compared to their frequencies in lymphoid tissue or in peripheral blood. Analysis of nasal PDC in a large number of individuals with differing pathologies revealed that PDC numbers in individuals treated with local glucocorticoids or with chronic allergy were strongly reduced, while they were considerably increased in individuals with acute infectious inflammation. The effect of glucocorticoid treatment was not PDC specific, since both PDC and MDC numbers in the nasal epithelium were reduced to the same extent. Reduced PDC numbers are unlikely to contribute to the therapeutic effect of glucocorticoid treatment in patients with nasal allergy, since for untreated patients PDC numbers were already low in our study. Our results are consistent with findings by others of nonselective reduction of all infiltrating immune cells (3, 26, 40) and of CD1a-positive and MHC-II-positive cells (2, 27, 40, 51) after topical corticosteroid treatment. Local corticosteroids have been shown to act through the inhibition of the production of chemokines such as TARC in the nasal mucosa (37).

Topical intranasal corticosteroids are very effective in the treatment of patients with allergic and perennial rhinitis. The decreased frequency of immune cells in the nasal mucosa provides an explanation for the therapeutic effects of glucocorticosteroids. Still, the use of local glucocorticosteroids remains a symptomatic therapy for allergy, asthma, and other chronic diseases.

In contrast to what was seen for patients receiving glucocorticosteroid treatment, a selective loss of PDC but not MDC in the nasal epithelium was found for individuals with chronic allergy. This was a surprising finding, since earlier studies reported that PDC numbers strongly increased during the acute phase of experimentally induced allergic rhinitis (31). At a first look, these results seem contradictory. However, the artificially induced acute inflammatory response in this previous study may have lead to an unselective influx of inflammatory cells, including PDC. In the previous study, no data were provided to support a selective increase of PDC in this setting. In our study, no acute allergic inflammation was induced; rather, individuals with a history of chronic nasal allergy that were asymptomatic at the time of the mucosal biopsy were examined. For these patients, repeated allergic reactions at the mucosal site may lead to a subclinical continuing bias of mucosal T cells towards Th2 and to a dominance of Th2 cytokines such as interleukin 4 (IL-4) over Th1 cytokines such as IFN-γ. Since IL-4 induces the rapid cell death of PDC (45), the chronic IL-4 environment may be responsible for the low numbers of PDC in the nasal epithelia of these patients, but other unknown mechanisms in these patients may also be involved. In this context, it is interesting to note that similar to what is seen for chronic nasal allergy and also for atopic dermatitis, reduced PDC numbers were found despite chronic inflammation (54); however, no consistent difference in blood PDC numbers was found when individuals with and without histories of allergy were compared (our own unpublished findings). The PDC-suppressive effect of the local Th1 response seems to outweigh that of IL-3, which has been reported to be produced by locally activated mast cells (44). Lower PDC numbers during chronic allergic inflammation strongly support the concepts that PDC are not required to maintain chronic allergic reactions and that low PDC numbers seem to be the consequence of allergic reactions.

Since PDC are required for antiviral defense, epithelia of patients with allergy might be more susceptible to viral infection. Indeed, asthmatic individuals are more susceptible to a severe course of rhinovirus infection (9), and a reduced capability to produce type I IFN upon viral infection was found (53). Interestingly, in another study, the induction of acute nasal allergic symptoms over a period of 10 days did not enhance susceptibility to rhinovirus infection (10). However, this experimental setting more resembles the situation for acute experimentally induced rhinitis, in which enhanced PDC numbers together with other infiltrating inflammatory cells were found by Farkas and colleagues (16).

Recently, it was reported that infection with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses mobilizes PDC and MDC to mucosal sites (19). In contrast to PDC numbers associated with cases of allergy, PDC numbers in nasal mucosa after acute viral infection were shown to stay high over a prolonged period of time (19). However, despite enhanced PDC numbers, some viral infections, such as RSV, do not lead to the development of protective immunity, and repeated infections are common. One reason for the absence of an adaptive immune response is the lack of IFN-α induction in PDC by RSV derived from such patients (natural isolates) (47), which might explain the missing development of an adaptive immune response. Of note is the fact that a similar cell is unable to produce large amounts of type I interferon upon stimulation (52) and therefore seems to be less effective in antiviral defense. This fact could result in a vicious circle in which allergic individuals are more susceptible to viral or bacterial infection.

In our study, high numbers of infiltrating PDC and MDC during acute infection at mucosal sites reflect the maximal alertness of the immune system at a time at which the type of microbial invader (bacteria or virus) is unknown. It has been reported that exposure to a pathogen results in the recruitment of dendritic cell precursors into the airway epithelium and that the initial wave of dendritic cell precursors arrives in advance of the neutrophil influx. Unlike the neutrophils, which rapidly transit into the airway lumen, the dendritic cell precursors remain within the epithelium during the acute inflammatory response. Dendritic cell precursors differentiate and develop the dendriform morphology typical of resident dendritic cells found in the normal epithelium. This recruitment of dendritic cells into the mucosa represents a mechanism of surveillance and defense (12, 39).

A Th1 type of immune response is required for an effective immune response against viral infection. In contrast, a Th2 response is mounted in the course of allergic reactions and is characterized by the production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Depending on the type of stimulus, PDC can support either a Th2 or a Th1 response. Therefore, high numbers of PDC in the nasal epithelium do not necessarily indicate a Th2 immune milieu. The former paradigm of PDC inducing a Th2 immune response (DC2) is no longer valid, since PDC were shown to produce large amounts of IFN-α upon CpG-mediated stimulation and are capable of producing IL-12 upon CpG- and CD40L-mediated stimulation (34, 35). Further support comes from the work of Farkas and colleagues, who showed that only nonstimulated PDC activate allergen-specific Th2 memory cells (15). However, in the case of CpG-A-mediated stimulation, allergen-dependent proliferation of Th2 memory cells was inhibited, and the IFN-γ production was markedly increased (16). CpG-A activated PDC produced a high level of IFN-α and augmented IFN-γ production in CD4+ T cells; both IFN-α and IFN-γ are cytokines with strong Th2-counteracting properties. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that mucosal PDC are promising targets for the development of CpG-based immunotherapeutic strategies against airway allergy (16).

The nasal mucosa is the first site of sensitization during the establishment of allergic rhinitis. Dendritic cells impact on this process by inducing either a Th1 or a Th2 immune response. For therapeutic intervention, reconstituting PDC and biasing PDC function towards Th1 could be useful for the treatment of both viral infection and allergy. Such bias of PDC function towards Th1 can be achieved by synthetic oligonucleotides as ligands for TLR7 (isRNA [28]) or for TLR9 (CpG DNA). Both oligonucleotide strategies alone or in combination have the potential to improve the therapeutic repertoire for viral infection and allergy in the near future. Intranasal application of the small-molecule TLR7 ligand imiquimod has already been shown to be safe and effective in terms of local IFN-α induction (7).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant DFG HA 2780/4-1, the Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung grant 10-2074/WO2 to B.W. and G.H., and the Monika-Kutzner-Stiftung and the Rudolf-Bartling-Stiftung grants given to B.W.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 August 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abb, J., H. Abb, and F. Deinhardt. 1983. Phenotype of human alpha-interferon producing leucocytes identified by monoclonal antibodies. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 52:179-184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachert, C., K. Hormann, R. Mosges, G. Rasp, H. Riechelmann, R. Muller, H. Luckhaupt, B. A. Stuck, and C. Rudack. 2003. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis and nasal polyposis. Allergy 58:176-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes, P. J. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of corticosteroids in allergic diseases. Allergy 56:928-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer, M., V. Redecke, J. W. Ellwart, B. Scherer, J. P. Kremer, H. Wagner, and G. B. Lipford. 2001. Bacterial CpG-DNA triggers activation and maturation of human CD11c-, CD123+ dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 166:5000-5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cella, M., D. Jarrossay, F. Facchetti, O. Alebardi, H. Nakajima, A. Lanzavecchia, and M. Colonna. 1999. Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type I interferon. Nat. Med. 5:919-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chehimi, J., S. E. Starr, H. Kawashima, D. S. Miller, G. Trinchieri, B. Perussia, and S. Bandyopadhyay. 1989. Dendritic cells and IFN-alpha-producing cells are two functionally distinct non-B, non-monocytic HLA-DR+ cell subsets in human peripheral blood. Immunology 68:488-490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clejan, S., E. Mandrea, I. V. Pandrea, J. Dufour, S. Japa, and R. S. Veazey. 2005. Immune responses induced by intranasal imiquimod and implications for therapeutics in rhinovirus infections. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 9:457-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordell, J. L., B. Falini, W. N. Erber, A. K. Ghosh, Z. Abdulaziz, S. MacDonald, K. A. Pulford, H. Stein, and D. Y. Mason. 1984. Immunoenzymatic labeling of monoclonal antibodies using immune complexes of alkaline phosphatase and monoclonal anti-alkaline phosphatase (APAAP complexes). J. Histochem. Cytochem. 32:219-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corne, J. M., C. Marshall, S. Smith, J. Schreiber, G. Sanderson, S. T. Holgate, and S. L. Johnston. 2002. Frequency, severity, and duration of rhinovirus infections in asthmatic and non-asthmatic individuals: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 359:831-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Kluijver, J., C. E. Evertse, J. K. Sont, J. A. Schrumpf, C. J. van Zeijl-van der Ham, C. R. Dick, K. F. Rabe, P. S. Hiemstra, and P. J. Sterk. 2003. Are rhinovirus-induced airway responses in asthma aggravated by chronic allergen exposure? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 168:1174-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diebold, S. S., T. Kaisho, H. Hemmi, S. Akira, and C. Reis e Sousa. 2004. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 303:1529-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dieu, M. C., B. Vanbervliet, A. Vicari, J. M. Bridon, E. Oldham, S. Ait-Yahia, F. Briere, A. Zlotnik, S. Lebecque, and C. Caux. 1998. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J. Exp. Med. 188:373-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dzionek, A., A. Fuchs, P. Schmidt, S. Cremer, M. Zysk, S. Miltenyi, D. W. Buck, and J. Schmitz. 2000. BDCA-2, BDCA-3, and BDCA-4: three markers for distinct subsets of dendritic cells in human peripheral blood. J. Immunol. 165:6037-6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dzionek, A., Y. Sohma, J. Nagafune, M. Cella, M. Colonna, F. Facchetti, G. Gunther, I. Johnston, A. Lanzavecchia, T. Nagasaka, T. Okada, W. Vermi, G. Winkels, T. Yamamoto, M. Zysk, Y. Yamaguchi, and J. Schmitz. 2001. BDCA-2, a novel plasmacytoid dendritic cell-specific type II C-type lectin, mediates antigen capture and is a potent inhibitor of interferon alpha/beta induction. J. Exp. Med. 194:1823-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farkas, L., K. Beiske, F. Lund-Johansen, P. Brandtzaeg, and F. L. Jahnsen. 2001. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (natural interferon-α/β-producing cells) accumulate in cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 159:237-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farkas, L., E. O. Kvale, F. E. Johansen, F. L. Jahnsen, and F. Lund-Johansen. 2004. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells activate allergen-specific TH2 memory cells: modulation by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 114:436-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P. 1993. Human natural interferon-alpha producing cells. Pharmacol. Ther. 60:39-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fokkens, W. J., D. M. Broekhuis-Fluitsma, E. Rijntjes, T. M. Vroom, and E. C. Hoefsmit. 1991. Langerhans cells in nasal mucosa of patients with grass pollen allergy. Immunobiology 182:135-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill, M. A., A. K. Palucka, T. Barton, F. Ghaffar, H. Jafri, J. Banchereau, and O. Ramilo. 2005. Mobilization of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells to mucosal sites in children with respiratory syncytial virus and other viral respiratory infections. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1105-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godthelp, T., W. J. Fokkens, A. Kleinjan, A. F. Holm, P. G. Mulder, E. P. Prens, and E. Rijntes. 1996. Antigen presenting cells in the nasal mucosa of patients with allergic rhinitis during allergen provocation. Clin. Exp. Allergy 26:677-688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartmann, E., B. Wollenberg, S. Rothenfusser, M. Wagner, D. Wellisch, B. Mack, T. Giese, O. Gires, S. Endres, and G. Hartmann. 2003. Identification and functional analysis of tumor-infiltrating plasmacytoid dendritic cells in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 63:6478-6487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann, G., J. Battiany, H. Poeck, M. Wagner, M. Kerkmann, N. Lubenow, S. Rothenfusser, and S. Endres. 2003. Rational design of new CpG oligonucleotides that combine B cell activation with high IFN-alpha induction in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:1633-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartmann, G., and A. M. Krieg. 2000. Mechanism and function of a newly identified CpG DNA motif in human primary B cells. J. Immunol. 164:944-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heil, F., H. Hemmi, H. Hochrein, F. Ampenberger, C. Kirschning, S. Akira, G. Lipford, H. Wagner, and S. Bauer. 2004. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science 303:1526-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemmi, H., O. Takeuchi, T. Kawai, T. Kaisho, S. Sato, H. Sanjo, M. Matsumoto, K. Hoshino, H. Wagner, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 2000. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 408:740-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holm, A. F., W. J. Fokkens, T. Godthelp, P. G. Mulder, T. M. Vroom, and E. Rijntjes. 1995. Effect of 3 months' nasal steroid therapy on nasal T cells and Langerhans cells in patients suffering from allergic rhinitis. Allergy 50:204-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holm, A. F., T. Godthelp, W. J. Fokkens, E. A. Severijnen, P. G. Mulder, T. M. Vroom, and E. Rijntjes. 1999. Long-term effects of corticosteroid nasal spray on nasal inflammatory cells in patients with perennial allergic rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 29:1356-1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hornung, V., M. Guenthner-Biller, C. Bourquin, A. Ablasser, M. Schlee, S. Uematsu, A. Noronha, M. Manoharan, S. Akira, A. de Fougerolles, S. Endres, and G. Hartmann. 2005. Sequence-specific potent induction of IFN-alpha by short interfering RNA in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Nat. Med. 11:263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hornung, V., S. Rothenfusser, S. Britsch, A. Krug, B. Jahrsdorfer, T. Giese, S. Endres, and G. Hartmann. 2002. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1-10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Immunol. 168:4531-4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jahnsen, F. L., E. Gran, R. Haye, and P. Brandtzaeg. 2004. Human nasal mucosa contains antigen-presenting cells of strikingly different functional phenotypes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 30:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jahnsen, F. L., F. Lund-Johansen, J. F. Dunne, L. Farkas, R. Haye, and P. Brandtzaeg. 2000. Experimentally induced recruitment of plasmacytoid (CD123high) dendritic cells in human nasal allergy. J. Immunol. 165:4062-4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kranzer, K., M. Bauer, G. B. Lipford, K. Heeg, H. Wagner, and R. Lang. 2000. CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides enhance T-cell receptor-triggered interferon-gamma production and up-regulation of CD69 via induction of antigen-presenting cell-derived interferon type I and interleukin-12. Immunology 99:170-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krieg, A. M. 2002. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:709-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krug, A., S. Rothenfusser, V. Hornung, B. Jahrsdorfer, S. Blackwell, Z. K. Ballas, S. Endres, A. M. Krieg, and G. Hartmann. 2001. Identification of CpG oligonucleotide sequences with high induction of IFN-alpha/beta in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:2154-2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krug, A., A. Towarowski, S. Britsch, S. Rothenfusser, V. Hornung, R. Bals, T. Giese, H. Engelmann, S. Endres, A. M. Krieg, and G. Hartmann. 2001. Toll-like receptor expression reveals CpG DNA as a unique microbial stimulus for plasmacytoid dendritic cells which synergizes with CD40 ligand to induce high amounts of IL-12. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:3026-3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krug, A., R. Uppaluri, F. Facchetti, B. G. Dorner, K. C. Sheehan, R. D. Schreiber, M. Cella, and M. Colonna. 2002. IFN-producing cells respond to CXCR3 ligands in the presence of CXCL12 and secrete inflammatory chemokines upon activation. J. Immunol. 169:6079-6083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambrecht, B. N. 2001. The dendritic cell in allergic airway diseases: a new player to the game. Clin. Exp. Allergy 31:206-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu, Y. J. 2005. IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:275-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McWilliam, A. S., D. Nelson, J. A. Thomas, and P. G. Holt. 1994. Rapid dendritic cell recruitment is a hallmark of the acute inflammatory response at mucosal surfaces. J. Exp. Med. 179:1331-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson, D. J., A. S. McWilliam, S. Haining, and P. G. Holt. 1995. Modulation of airway intraepithelial dendritic cells following exposure to steroids. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 151:475-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Doherty, U., M. Peng, S. Gezelter, W. J. Swiggard, M. Betjes, N. Bhardwaj, and R. M. Steinman. 1994. Human blood contains two subsets of dendritic cells, one immunologically mature and the other immature. Immunology 82:487-493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olweus, J., A. BitMansour, R. Warnke, P. A. Thompson, J. Carballido, L. J. Picker, and F. Lund-Johansen. 1997. Dendritic cell ontogeny: a human dendritic cell lineage of myeloid origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12551-12556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pashenkov, M., Y. M. Huang, V. Kostulas, M. Haglund, M. Soderstrom, and H. Link. 2001. Two subsets of dendritic cells are present in human cerebrospinal fluid. Brain 124:480-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plaut, M., J. H. Pierce, C. J. Watson, J. Hanley-Hyde, R. P. Nordan, and W. E. Paul. 1989. Mast cell lines produce lymphokines in response to cross-linkage of Fc epsilon RI or to calcium ionophores. Nature 339:64-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rissoan, M. C., V. Soumelis, N. Kadowaki, G. Grouard, F. Briere, R. de Waal Malefyt, and Y. J. Liu. 1999. Reciprocal control of T helper cell and dendritic cell differentiation. Science 283:1183-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothenfusser, S., V. Hornung, A. Krug, A. Towarowski, A. M. Krieg, S. Endres, and G. Hartmann. 2001. Distinct CpG oligonucleotide sequences activate human gamma delta T cells via interferon-alpha/-beta. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:3525-3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlender, J., V. Hornung, S. Finke, M. Gunthner-Biller, S. Marozin, K. Brzozka, S. Moghim, S. Endres, G. Hartmann, and K. K. Conzelmann. 2005. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 7- and 9-mediated alpha/beta interferon production in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells by respiratory syncytial virus and measles virus. J. Virol. 79:5507-5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegal, F. P., N. Kadowaki, M. Shodell, P. A. Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, K. Shah, S. Ho, S. Antonenko, and Y. J. Liu. 1999. The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science 284:1835-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Summers, K. L., B. D. Hock, J. L. McKenzie, and D. N. Hart. 2001. Phenotypic characterization of five dendritic cell subsets in human tonsils. Am. J. Pathol. 159:285-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeda, K., T. Kaisho, and S. Akira. 2003. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:335-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Till, S. J., M. R. Jacobson, F. O'Brien, S. R. Durham, A. KleinJan, W. J. Fokkens, S. Juliusson, and O. Lowhagen. 2001. Recruitment of CD1a+ Langerhans cells to the nasal mucosa in seasonal allergic rhinitis and effects of topical corticosteroid therapy. Allergy 56:126-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vuckovic, S., D. Khalil, N. Angel, F. Jahnsen, I. Hamilton, A. Boyce, B. Hock, and D. N. Hart. 2005. The CMRF58 antibody recognizes a subset of CD123hi dendritic cells in allergen-challenged mucosa. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77:344-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wark, P. A., S. L. Johnston, F. Bucchieri, R. Powell, S. Puddicombe, V. Laza-Stanca, S. T. Holgate, and D. E. Davies. 2005. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J. Exp. Med. 201:937-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wollenberg, A., M. Wagner, S. Gunther, A. Towarowski, E. Tuma, M. Moderer, S. Rothenfusser, S. Wetzel, S. Endres, and G. Hartmann. 2002. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: a new cutaneous dendritic cell subset with distinct role in inflammatory skin diseases. J. Investig. Dermatol. 119:1096-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zou, W., V. Machelon, A. Coulomb-L'Hermin, J. Borvak, F. Nome, T. Isaeva, S. Wei, R. Krzysiek, I. Durand-Gasselin, A. Gordon, T. Pustilnik, D. T. Curiel, P. Galanaud, F. Capron, D. Emilie, and T. J. Curiel. 2001. Stromal-derived factor-1 in human tumors recruits and alters the function of plasmacytoid precursor dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 7:1339-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]