Abstract

Objectives To quantify the risk of Alzheimer's disease in users of all non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and users of aspirin and to determine any influence of duration of use.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies published between 1966 and October 2002 that examined the role of NSAID use in preventing Alzheimer's disease. Studies identified through Medline, Embase, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, and the Cochrane Library.

Results Nine studies looked at all NSAIDs in adults aged > 55 years. Six were cohort studies (total of 13 211 participants), and three were case-control studies (1443 participants). The pooled relative risk of Alzheimer's disease among users of NSAIDs was 0.72 (95% confidence interval 0.56 to 0.94). The risk was 0.95 (0.70 to 1.29) among short term users (< 1 month) and 0.83 (0.65 to 1.06) and 0.27 (0.13 to 0.58) among intermediate term (mostly < 24 months) and long term (mostly > 24 months) users, respectively. The pooled relative risk in the eight studies of aspirin users was 0.87 (0.70 to 1.07).

Conclusions NSAIDs offer some protection against the development of Alzheimer's disease. The appropriate dosage and duration of drug use and the ratios of risk to benefit are still unclear.

Introduction

Pharmacological treatments of Alzheimer's disease are limited. Recent observational studies, however, have shown that use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may protect against the development of the disease,1,2 possibly through their anti-inflammatory properties.3 Results of research have varied and at least one study found no effect.4 One limitation of the studies with negative results may have been their small sample sizes. In such circumstances, a systematic review should be able to quantify a pooled measure of effect from the existing studies. Though one previous systematic review showed a beneficial effect, it included only three studies of NSAIDs.5

There remain some unanswered questions. For example, we do not know whether the benefit is a class effect or whether it is restricted to specific agents; the role of aspirin in particular has not been examined.4 We therefore carried out an updated meta-analysis to quantify the risk of Alzheimer's disease in NSAID users and specifically in aspirin users and to discuss the influence of the duration of use on the potential prevention of Alzheimer's disease.

Methods

Study selection—We systematically searched Medline (1966 to October 2002 via Ovid), Embase (1974 to October 2002), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (a database extending back to 1975 that includes over 750 journals focused on drug therapy), and the Cochrane Library (issue 2, 2002) for all relevant English language articles. Firstly, medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and textwords including Alzheimer disease, dementia, and cognition disorders were entered. Secondly, we searched using the MeSH terms and textwords anti-inflammatory agents, non-steroidal, and aspirin. We then combined the two searches, retrieved all relevant articles based on consensus among authors, and searched reference lists of retrieved articles to find other potentially relevant articles.

Data extraction—We included a study if it had clearly stated diagnostic criteria for the outcome of Alzheimer's disease or dementia and explicitly described exposure to NSAIDs. Studies also had to present data on relative risks or odds ratios or had to at least present enough data to allow these to be calculated. We excluded studies that examined exposure to other analgesics, studies in which vascular dementia was the primary outcome as the biology of this condition differs from that of Alzheimer's disease,6 and those that might have results duplicated elsewhere as the inclusion of duplicate results can seriously impair the validity of a meta-analysis.7 If two studies used the same study population during the same time period we included only the study with the stronger design (for example, larger sample size, longer follow up, better control of confounding factors). We defined use of NSAIDs as any use any time during the study period. For those studies that explicitly classified NSAID use with respect to duration of exposure, we attempted to classify use as either short, intermediate, or long term (see table 4). All studies were reviewed by two of the authors (AS, ME), and discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the third author (SG).

Analysis—We carried out three separate analyses. Firstly, we selected studies that explored the risk of Alzheimer's disease in users of all NSAIDs. Secondly, we looked at the risk of Alzheimer's disease specifically among aspirin users. Thirdly, we looked at the risk of Alzheimer's disease according to duration of use of NSAIDs. We used the random effects model to calculate pooled relative risks and 95% confidence intervals as this model accounts for heterogeneity between studies.8 Odds ratios were considered an approximation of relative risks. We combined relative risks (from cohort studies) and odds ratios (from case-control studies) only if the result of the Q test of heterogeneity was negative. Because tests of heterogeneity may be underpowered to detect heterogeneity between studies when the number of studies is small (for instance, < 20),9 we also explored heterogeneity graphically10 and quantitatively using the R(I) statistic.11 This allows the investigator to determine whether classic tests of heterogeneity would have sufficient power to detect heterogeneity between studies. Publication bias was assessed with a funnel plot. The analyses were done with HEpiMA version 2.3.12

Results

We identified 15 potential studies.1,2,4,13–24 We excluded one study13 because the data in it were used in a more recent cohort study.2 We excluded two other studies14,15 because they were case-control studies that used a population of Rotterdam residents recently used in a larger cohort study.1 Four studies looked at the risk of Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia relative to NSAIDs use, but all used overlapping patient data from the same database (the Canadian Study of Health and Aging).16–19 We chose one of these articles for inclusion for the first analysis as it provided the largest sample size of patients across Canada.19 However, for the second analysis (confined to aspirin users) we included the only study among the four that provided data specifically on aspirin use in patients with Alzheimer's disease.17 Only two of the 15 studies provided data specifically on the outcome of vascular dementia,1,18 so we did not analyse this outcome separately. Four studies provided data on the effects of duration of treatment.1,2,21,24

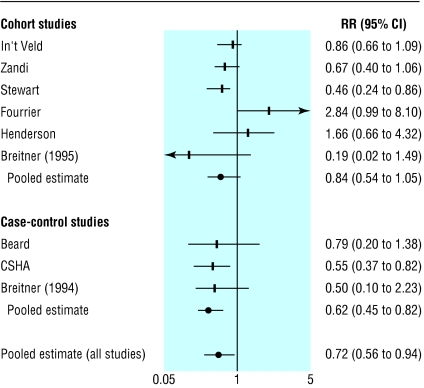

We included nine studies in the analysis of use of any NSAID.1,2,4,19–24 Six were cohort studies (13 211 participants, table 1)1,2,4,21,23,24 and three were case-control studies (1443 participants, table 2).19,20,22 We included eight studies for the analysis of aspirin users,1,2,17,20–24 of which five were cohort studies1,2,21,23,24 and three were case-control studies17,20,22 (table 3). The pooled relative risk of Alzheimer's disease was 0.84 (0.54 to 1.05) among users of NSAIDs in the cohort studies, 0.62 (0.45 to 0.82) among users of NSAIDs in the case-control studies (table 3), and 0.72 (0.56 to 0.94) in both (fig 1). The pooled relative risk for aspirin users was 0.87 (0.70 to 1.07, P = 0.79 for heterogeneity). Only the study by In't Veld et al had a category for “short term” (< 1 month) use.1 The relative risk of Alzheimer's disease for this category was 0.95 (0.70 to 1.29). For intermediate and long term NSAID users the relative risks were 0.83 (0.65 to 1.06, P = 0.34 for heterogeneity) and 0.27 (0.13 to 0.58, P = 0.06 for heterogeneity), respectively (table 4).

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort studies evaluating role of NSAIDs and aspirin in preventing Alzheimer's disease. All were community studies

|

Adjusted relative risk or odds ratio (95% CI)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | No | Age (years) | Diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease | NSAID assessment | Variable adjustment | Event rate (cases/person years) with NSAIDs v non-NSAIDs | NSAID | Aspirin |

| In't Veld1 | 6989 | >55 | Clinical investigation | Prescription database | Age, sex, smoking, education, diabetes, antihypertensives, acid blockers | 184/29 359 v 210/16 715 | 0.86 (0.66 to 1.09) | 1.3 (0.97 to 1.74) |

| Zandi2 | 3227 | >65 | Interviews and clinical investigation | Patient interviews | Age, sex, APOE gene, education | 79/7048 v 22/3017 | 0.67 (0.40 to 1.06) | 0.82 (0.54 to 1.23) |

| Stewart21 | 1686 | <65 | Clinical investigation | Patient interviews | Age, sex, education, year of cohort entry | Only adjusted relative risks presented | 0.46 (0.24 to 0.86) | 0.85 (0.53 to 1.37) |

| Fourrier4 | 516 | >65 | MMSE scores† | Patient interviews | Age, education | Only adjusted relative risks presented | 2.84 (0.99 to 8.10) | — |

| Henderson23 | 588 | 80* | Interviews and clinical investigation | Patient interviews | Age, sex, education, stroke, APOE gene, arthritis medication | Only adjusted relative risks presented | 1.66 (0.64 to 4.32) | 1.79 (0.72 to 4.45) |

| Breitner 199524 | 205 | NS | Interviews and autopsy | Patient interviews | Age, sex, acid blockers, insulin | Only adjusted relative risks presented | 0.19 (0.02 to 1.49) | 0.37 (0.17 to 0.79) |

NS=not stated, all older adults. APOE=apolipoprotein E. *Mean age. †Folstein mini-mental state examination.

Table 2.

Characteristics of case-control studies evaluating role of NSAIDs and aspirin in preventing Alzheimer's disease

|

Adjusted relative risk or odds ratio (95% CI)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (setting) | No | Age | Diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease | NSAID assessment | Variable adjustment | Cases | Controls | NSAID | Aspirin |

| Breitner 199422 (WW

II twins)

|

46

|

75*

|

Telephone interview

|

Questionnaire

|

None

|

Only crude OR presented

|

0.50 (0.10 to 2.23)

|

0.56 (0.16 to 1.81)

|

|

| Lindsay17 (community) † | 4915 | >70 | Clinical investigation | Questionnaire | Age, sex, education | 45/152 | 1224/3086 | — | 0.85 (0.55 to 1.31) |

| CSHA19 (community and institution)‡ | 793 | >65 | Clinical investigation | Questionnaire | Age, sex, education, community or hospital status | 61/224 | 205/529 | 0.55 (0.37 to 0.82) | — |

| Beard20 (community) | 604 | >65 | Medical records | Medical records | Age and sex matched | 9/155 | 18/157 | 0.79 (0.20 to 1.38) | 0.90 (0.51 to 1.59) |

WW II=second world war. *Mean age. †Only data on aspirin used from this study. ‡Canadian study of health and ageing.

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies of aspirin and Alzheimer's disease

| Study | No | Pooled relative risk or odds ratio (95%CI) | P value for heterogeneity | R(I) statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSAIDs | ||||

| Cohort studies | 6 | 0.84 (0.54 to 1.05) | 0.04 | 0.58 |

| Case-control studies | 3 | 0.62 (0.45 to 0.82) | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| All studies | 9 | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.94) | 0.06 | 0.49 |

| Aspirin | ||||

| Cohort studies | 5 | 0.85 (0.71 to 1.03) | 0.76 | 0.00 |

| Case-control studies | 3 | 0.84 (0.61 to 1.16) | 0.77 | 0.00 |

| All studies | 8 | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.07) | 0.79 | 0.00 |

Fig 1.

Relative risks (95% confidence intervals) from studies of NSAID use and effect on Alzheimer's disease

Table 4.

Relative risks (95% confidence interval) for NSAID users, stratified by length of use

| Study | Short term (<1 month) | Intermediate term | Long term |

|---|---|---|---|

| In't Veld1 | 0.95 (0.70 to 1.29) | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.11) (>1-23 months) | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.83) (≥24 months) |

| Zandi2 | — | 1.23 (0.54 to 2.46) (≤24 months) | 0.51 (0.18 to 1.15) (>24 months) |

| Stewart21 | — | 0.65 (0.33 to 1.29) (<24 months) | 0.40 (0.19 to 0.84) (>24 months) |

| Breitner 24 | — | 0.19 (0.02 to 1.49) (>1-12 months) | 0.08 (0.02 to 0.26)* (>12 months) |

| Pooled relative risk | 0.95 (0.70 to 1.29) | 0.83 (0.65 to 1.06) | 0.27 (0.13 to 0.58) |

Narrow confidence interval may result from larger proportion of participants exposed for >12 months (17/142) than proportion exposed for 1-12 months (4/129) in original paper. We performed sensitivity analysis by calculating pooled RR for long term users with and without Breitner study to examine effect on results. Pooled RR for long term users changed to 0.4 (0.24 to 0.67), which does not change our findings.

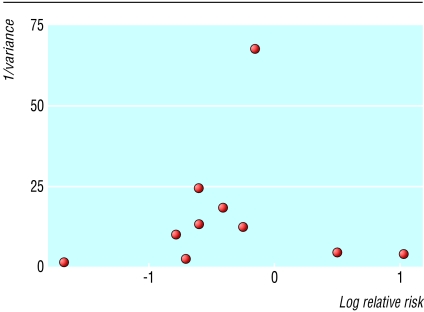

The results from cohort studies and case-control studies were generally similar for both analyses (table 3), with little statistical heterogeneity. We did, however, find slight heterogeneity among the cohort studies for any NSAID use. The source of this heterogeneity was the study by Fourrier et al,4 possibly because they diagnosed dementia using the Folstein mini-mental state examination. This has limited accuracy in distinguishing between early Alzheimer's disease and normal cognition.25 Despite the relatively small number of studies, funnel plot analysis did not indicate significant publication bias (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Funnel plot of studies of NSAID use and Alzheimer's disease (0 on the x axis (natural logarithm of relative risk) represents null effect). Visual inspection of funnel plot does not indicate publication bias

Discussion

Our results, based on analysis of a large number of patients, show that use of an NSAID lowers the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. The magnitude of this benefit is consistent with that found in a recent large study with long follow up data.1 Our results also show a greater benefit with long term rather than intermediate term use (table 4). This may be one explanation for the lack of benefit seen in two of the studies included in this review4,23 in which participants were followed up for a relatively short period and therefore may not have had enough time to benefit from the protective effects of NSAIDs. An editorial by Breitner and Zandi suggested that there may be an association between duration and response for NSAIDs in preventing Alzheimer's disease, with at least two years of exposure necessary to obtain full benefit.3

The meta-analysis also indicates that aspirin has a protective effect, although this result was not significant (table 3), probably because of the small number of studies that specifically evaluated the effects of aspirin. There are theoretical reasons why aspirin may differ from other NSAIDs in terms of effectiveness.26,27 At present, however, there are insufficient data on which to base any comparisons between aspirin and other NSAIDs in the prevention of dementia.

Although a few small randomised controlled trials have shown some beneficial effects on cognition with use of NSAIDs in patients with established Alzheimer's disease,28,29 no randomised controlled trial to date has looked at the prevention. Currently the relative benefit of COX 2 selective inhibitors over traditional NSAIDs is purely speculative. However, studies are now underway to determine the role of COX 2 selective inhibitors in the prevention of Alzheimer's disease.30,31

Limitations of study

Publication bias may have influenced our results because negative studies are less likely to be published. Although this trend does not seem to be reflected in our funnel plot we cannot exclude it as the funnel plot may not detect publication bias when the number of studies is small. Secondly, the possibility of confounding and bias may be more significant in meta-analyses of observational studies than in meta-analyses of randomised trials, and statistical adjustment for confounding variables in observational studies may not entirely resolve these problems. Case-control studies are particularly at risk of biased patient selection that may unduly weight the outcome in favour of the exposure under evaluation. In our review, the case-control studies all tended to support NSAIDs having a protective effect, while the cohort studies had more variable results (fig 1). Another relevant bias is recall bias as in some of the studies information on NSAID use was obtained by interviewing patients.

What is already known on this topic

Few treatments exist for people with Alzheimer's disease, and recent efforts have focused on preventive measures

Observational studies have suggested that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) protect against Alzheimer's disease, but results have been inconsistent

What this study adds

Use of NSAIDs seems to lower the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease in adults aged > 55 years

Benefits may be greater the longer NSAIDs are used

The evidence behind the potential preventive use of aspirin is not robust

There were important differences in study design, including the assessment of exposure and adjustments for confounding factors (see tables 1 and 2). Adjustments were not always made for important risk factors for Alzheimer's disease such as family history and apolipoprotein E status. These differences in study design may give rise to clinical heterogeneity, which may not be fully reflected in the results of our statistical tests of heterogeneity. Finally, the restriction of our systematic review to English language studies may have resulted in language bias with potentially relevant studies published in other languages being missed.32

Conclusion

In light of the growing evidence from observational studies and the current absence of evidence from randomised controlled trials, our systematic review lends support to the hypothesis that NSAIDs may protect against the development of Alzheimer's disease. The appropriate dose, duration, and ratios of risk to benefit are still unclear.

We thank Paula Rochon (Kunin-Lunenfeld Applied Research Unit and Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Canada) for reviewing the manuscript.

Contributors: ME and AS initiated the project. ME, SG, and AS screened and extracted the data. ME and SG analysed the data. All authors participated in discussing the results and in writing the paper. ME will act as guarantor for the paper.

Funding: AS is funded by a Parkinson Disease Research Education and Clinical Center (PADRECC) grant. ME and SG are funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) postdoctoral fellowship awards. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.In't Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, Launer LJ, Van Duijin CM, Stijnen T, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 2001;345: 1515-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zandi PP, Anthony JC, Hayden KM, Mehta K, Mayer L, Brietner JC, et al. Reduced incidence of AD with NSAID but not H2 receptor antagonists: the Cache County study. Neurology 2002;59: 880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitner JC, Zandi PP. Do nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease? N Engl J Med 2001;345: 1567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fourrier A, Letenneur L, Begaud B, Dartigues JF. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and cognitive function in the elderly: inconclusive results from a population-based cohort study. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49: 1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGeer PL, Schulzer M, McGeer EG. Arthritis and anti-inflammatory agents as possible protective factors for Alzheimer's disease: a review of 17 epidemiologic studies. Neurology 1996;47: 425-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amar K, Wilcock G. Vascular dementia. BMJ 1996;312: 227-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huston P, Moher D. Redundancy, disaggregation, and the integrity of medical research. Lancet 1996;347: 1024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7: 177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy RJ, Thompson SG. Detecting and describing heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med 1998;17: 841-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker AM, Martin-Moreno JM, Artalejo FR. Odd man out: a graphical approach to meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 1988;78: 961-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takkouche B, Cadarso-Suarez C, Spiegelman D. Evaluation of old and new tests of heterogeneity in epidemiologic meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150: 206-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa-Bouzas J, Takkouche B, Cadarso-Suarez C, Spiegelman D. HEpiMA: software for the identification of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2001;64: 101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anthony JC, Breitner JC, Zandi PP, Meyer MR, Jurasova I, Norton MC, et al. Reduced prevalence of AD in users of NSAIDs and H2 receptor antagonists: the Cache County study. Neurology 2000;54: 2066-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen K, Launer LJ, Ott A, Hoes AW, Breteler MM, Hofman A. Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decrease the risk for Alzheimer's disease? The Rotterdam study. Neurology 1995;45: 1441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.In't Veld BA, Launer LJ, Hoes AW, Ott A, Hofman A, Breteler MM, et al. NSAIDs and incident Alzheimer's disease. The Rotterdam study. Neurobiol Aging 1998;19: 607-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfson C, Perrault A, Moride Y, Esdaile JM, Abenhaim L, Momoli F. A case-control analysis of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and Alzheimer's disease: are they protective? Neuroepidemiology 2002;21: 81-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, Hebert R, Helliwell B, Hill GB, et al. Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian study of health and aging. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156: 445-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hebert R, Lindsay J, Verrault R, Rockwood K, Hill G, Dubois MF. Vascular dementia: incidence and risk factors in the Canadian study of health and aging. Stroke 2000;31: 1487-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Canadian study of health and aging: risk factors for Alzheimer's disease in Canada. Neurology 1994;44: 2073-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beard CM, Waring SC, O'Brien PC, Kurland LT, Kokman E. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1980 through 1984. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73: 951-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart WF, Kawas C, Corrada M, Metter EJ. Risk of Alzheimer's disease and duration of NSAID use. Neurology 1997;48: 626-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breitner JC, Gau MW, Welsh KA, Plassman BL, McDonald WM, Helms MJ, et al. Inverse association of anti-inflammatory treatments and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1994;44: 227-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson AS, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Jacomb PA, Korten AE. Aspirin, anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;12: 926-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breitner JC, Welsh KA, Helms MJ, Gaskell PC, Gau BA, Roses AD, et al. Delayed onset of Alzheimer's disease with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and histamine H2 blocking drugs. Neurobiol Aging 1995;16: 523-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle SH, Cauley JA, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M. Cognitive tests that best discriminate between presymptomatic AD and those who remain nondemented. Neurology 2000;55: 1847-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho L, Purohit D, Haroutunian V, Luterman JD, Willis F, Naslund J, et al. Neuronal cyclooxygenase 2 expression in the hippocampal formation as a function of the clinical progression of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2001;58: 487-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cryer B, Feldman M. Cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 selectivity of widely used non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 1998;104: 413-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aisen PS, Schmeidler J, Pasinetti GM. Randomized pilot study of nimesulide treatment in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 2002;58: 1050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scharf S, Mander A, Ugoni A, Vajda F, Christophidis N. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of diclofenac/misoprostol in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1999;53: 197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aisen PS. Evaluation of selective COX-2 inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23: S35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2001;58: 1985-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger M, Zellweger-Zähner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet 1997;350: 326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]