Abstract

Folding of the major population of Tetrahymena intron RNA into the catalytically active structure is trapped in a slow pathway. In this report, folding of Candida albicans intron was investigated using the trans-acting Ca.L-11 ribozyme as a model. We demonstrated that both the catalytic activity (kobs) and compact folding equilibrium of Ca.L-11 are strongly dependent on Mg2+ at physiological concentrations, with both showing an Mg2+ Hill coefficient of 3. Formation of the compact structure of Ca.L-11 is shown to occur very rapidly, on a subsecond time scale similar to that of RNase T1 cleavage. Most of the ribozyme RNA population folds into the catalytically active structure with a rate constant of 2 min–1 at 10 mM Mg2+; neither slower kinetics nor obvious Mg2+ inhibition is observed. These results suggest that folding of the Ca.L-11 ribozyme is initiated by a rapid magnesium-dependent RNA compaction, which is followed by a slower searching for the native contacts to form the catalytically active structure without interference from the long-lived trapped states. This model thus provides an ideal system to address a range of interesting aspects of RNA folding, such as conformational searching, ion binding and the role of productive intermediates.

INTRODUCTION

As a representative group I intron ribozyme, the Tetrahymena intron from its rRNA gene has been extensively studied regarding catalysis, folding and structure since it was discovered two decades ago (1–3). The two-step transesterification catalysis by Tetrahymena intron is similar to that of all self-splicing group I introns studied thus far (4–8). Despite the similarity of all self-splicing group I introns, whose secondary structure includes nine conserved base-paired helices denoted P1–P9, their primary sequences vary greatly, resulting in characteristic local secondary structures. For example, non-conserved helices vary in number, location and structure among individual introns (9). It is reasonable to predict that the differences in their primary sequences and local secondary structures result in differences in the details of the folding strategies of different introns. Consistent with this prediction, a protein factor CYT18 is required to stabilize the catalytic core of mitochondrial group I introns from Neurospora crassa for efficient in vitro splicing (10,11) and CBP2 is required to capture yeast mitochondrial bI5 intron from a collapsed state to its active structure (12,13), while self-folding of the Tetrahymena intron ribozyme encounters a kinetic trap (14). Free hydroxyl radical footprinting and native gel analysis have been extensively used to monitor the folded structure of the Tetrahymena intron (15–17). However, the completely folded structure (16) does not correspond to full ribozyme activity, i.e. the catalytically active structure (18), probably due to misfolding of some ribozyme molecules. Therefore, exploring correct folding strategies of group I introns remains important for understanding the mechanism of catalysis.

Results from the ensemble folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme (19–21) and FRET-monitored single molecule folding (18) suggest that this intron folds into its catalytically active states through at least three pathways. Only a small fraction (12%) of the Tetrahymena ribozyme folds into its native state via two faster pathways with the observed rate constants of 1 and 0.016 s–1, respectively. A major population of the ribozyme folds through the slow pathway that involves Mg2+-stabilized kinetic traps (20,22). Kinetic traps in Tetrahymena ribozyme folding can be eliminated by introducing mutations that change some native tertiary interactions (23,24). Trap-free folding has been reported for the catalytic domain of P RNA (C-domain) (25) and the catalytic core of the bI5 ribozyme which requires CBP2 protein to achieve its active structure at physiological Mg2+ concentration (12).

The primary goal of this study is to uncover the folding mechanism of Ca.LSU, a 379-nt self-splicing group I intron from the 26S rRNA of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans and consisting of nine conserved helices and non-conserved helices including P2.1, P5abc, P9.1 and P9.2 (4,26). Although homologs of these non-conserved helices are also present in the Tetrahymena intron, substantial differences exist in their primary sequence and local secondary structures. For example, the P5abc subdomain of Ca.LSU differs in secondary structure from the Tetrahymena intron by lacking a branched folded structure. We have produced a Ca.LSU-derived ribozyme, Ca.L-11, that cleaves its 11-nt RNA substrate in trans. This simpler model ribozyme has been used to study the folding mechanism of Ca.LSU intron ribozyme with a focus on the folding pathway to the catalytically active structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Ca.L-11 ribozyme and 5′-end-labeled RNA substrate

Using primers Ca/L-11 T7 (taa tac gac tca cta tag gag gca aaa gta ggg ac) and Ca/R-1 (att gct cca aga aat cgc ttt), Ca.L-11 ribozyme DNA flanked by a T7 promoter at its 5′ end was PCR amplified from the genomic DNA of C.albicans. The amplified DNA was transcribed in vitro into Ca.L-11 ribozyme RNA by T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) for 3 h and then isolated on a 5% polyacylamide/7 M urea gel (26). The Ca.L-11 RNA band was visualized by UV shadowing (254 nm), excised, electro-eluted and recovered by ethanol precipitation. The ribozyme concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm, assuming ε260 = 3 × 106 M–1cm–1. RNA oligonucleotide Ca/sub-11 was synthesized by Dharmacon Research, Inc. (Lafayette, IN). The 2′-ACE-protected RNA was deprotected following the manufacturer’s protocol (www.dharmacon.com) prior to use, and concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. The RNA oligonucleotide was then labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (5000 Ci/mmol, Furui Biotech, Beijing) by T4 polynucleotide kinase (BRL). The unincorporated [γ-32P]ATP was removed by passage through a G-25 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Magnesium dependence of substrate cleavage

Each reaction (5 µl) contained 10 nM Ca.L-11 ribozyme, 0.1 mM GTP, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 50 nM [5′-32P]Ca/sub-11 and the indicated concentrations of MgCl2, varying from 0 to 10 mM. Reactions were run at 37°C for 0–150 min and stopped by adding an equal volume of loading buffer containing 20 mM EDTA and 7 M urea. Samples were then placed on ice until electrophoresis on a 15% polyacylamide/ 7 M urea gel that was then exposed to X-ray film. Signals on X-ray films were analyzed by a Kodak 290 digital camera and 1D 3.5 image analysis software. The data were plotted using the GraphPad Prism 3.0 program (www.graphpad.com).

RNase T1 footprinting assay

The ribozyme was dephosphorylated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (BRL), phenol extracted and ethanol precipitated. The precipitated ribozyme was then 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and gel purified as described above. The labeled Ca.L-11 ribozyme (∼5 ng) in 16 µl of 62.5 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5 was denatured at 95°C for 1 min, annealed at 37°C for 2 min and then chilled on ice. Each sample was then allowed to fold at 37°C for 5 min with 2 µl of 10× folding buffer containing the desired concentrations of MgCl2. RNase T1 (2 µl of 0.7 or 1.2 U/µl) was then added to initiate the T1 cleavage reaction, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 min. Cleavage was stopped by adding 30 µl of phenol–chloroform (1:1), immediately followed by vigorous vortexing. After centrifugation, 16 µl of supernatant was removed and put into an equal volume of loading buffer, and stored at –70°C until electrophoresis. All samples were fractionated on 8% polyacylamide/7 M urea sequencing gels. Gels were exposed to Phosphor screens that were scanned and analyzed using a variable scanner Typhoon 9200 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), except for the gel in Figure 3 which was exposed to X-ray film. Data were plotted using GraphPad Prism.

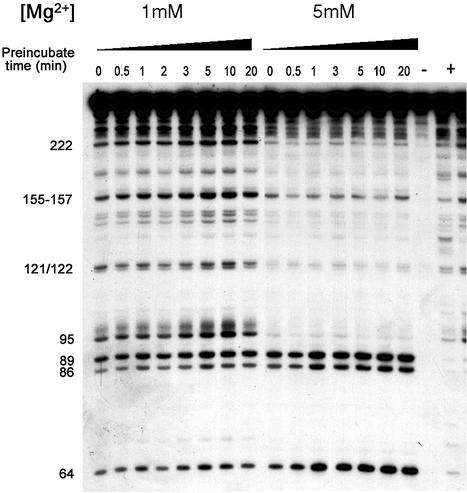

Figure 3.

Rapid compaction of Ca.L-11 ribozyme RNA. The 5′-end-labeled Ca.L-11 was folded at 1 and 5 mM Mg2+ for the indicated periods of time, then cleaved by RNase T1 (0.1 U/µl) for 1 min and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods.

Measurement of koverall

The gel-purified ribozyme (final concentration 20 nM) was denatured at 95°C for 1 min and then was annealed at 37°C for 2 min in 2.5 µl of 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5. An equal volume of 2× folding buffer with the desired concentration of Mg2+ was then added to initiate folding. Folding was allowed to proceed for various times before the cleavage reaction was initiated by adding 5 µl of reaction mixture containing [5′- 32P]Ca/sub-11, GTP and Tris–HCl pH 7.5 to reach the final concentrations of 30 nM, 0.1 mM and 50 mM, respectively. Appropriate concentrations of MgCl2 were included in the reaction mix so that all the cleavage reactions were carried out at 10 mM MgCl2. Cleavage reactions were run at 37°C for 1 min, stopped and analyzed as described above.

Initial product burst kinetics

The substrate cleavage reaction was initiated by adding reaction mixture to the annealed ribozyme (final concentrations: 50 nM substrate and ribozyme, 0.1 mM GTP, 10 mM Mg2+, and 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5). Reactions were incubated for the indicated periods of time and stopped by adding an equal volume of 100 mM EDTA. Reactions were fractionated on 15% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels that were exposed to Phosphor screens followed by scanning and analysis with the Typhoon 9200. Data were plotted using GraphPad Prism.

RESULTS

Ca.L-11-catalyzed trans-cleavage is dependent on magnesium at physiological concentrations

Lacking the first 11 nt and ωG of C.albicans intron Ca.LSU, Ca.L-11 ribozyme was constructed to resemble the L-21 ScaI trans-acting derivative of the Tetrahymena intron. This ribozyme efficiently catalyzes the +6 site-specific cleavage (reaction below) of the RNA oligonucleotide GCCUCUA5 (Ca/sub-11), which mimics the first step transesterification reaction of self-splicing of the group I intron from C.albicans: GCCUCUA5 + G→GCCUCU + GA5.

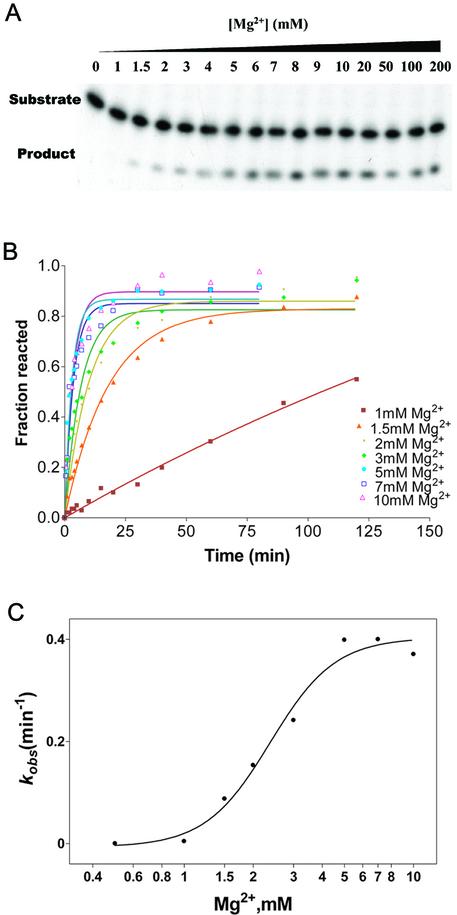

The effect of Mg2+ on Ca.L-11-catalyzed substrate cleavage was monitored either by running the reaction at 37°C for 3 min (Fig. 1A) or by measuring the rate of the observed first-order reaction (kobs) (Fig. 1B and C) in the presence of Mg2+ varying in concentration from 0 to 10 mM. We found that the catalytic activity of Ca.L-11 increased with Mg2+ at physiological concentrations from 1.5 to 6 mM. The Mg2+ required for half-maximal catalytic activity (Mg1/2) is 2.37 mM, with a Hill coefficient of 3.1 Mg2+ ions (Fig. 1C). Note that no further increase was observed when the Mg2+ concentration was >6 mM, and very little catalytic activity was observed at 1 mM Mg2+. The strong Mg2+ dependence of Ca.L-11 catalysis only at physiological magnesium concentrations suggests that the in vitro catalysis of this ribozyme might reflect that in vivo.

Figure 1.

Magnesium-dependent Ca.L-11 catalysis. (A) A gel showing substrate (50 nM) cleavage catalyzed by 10 nM Ca.L-11 at various Mg2+ concentrations. All reactions were run at 37°C for 3 min and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The observational first-order reaction constant (kobs) at various Mg2+ concentrations was determined by plotting the fraction of the cleaved substrate against cleaving time and then calculated by fitting curves to a single exponential. (C) kobs versus [Mg2+] fitted to the Hill equation kobs = kmax × [Mg2+ ]n/(Mg1/2n + [Mg2+ ]n), n = 3.08 ± 0.86, Mg1/2 = 2.37 ± 0.55 mM.

Compact folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme is Mg2+ dependent and rapid

RNase T1 (EC 3.1.27.3) is a small (∼11 kDa) endoribonuclease that specifically cleaves single-stranded RNA 3′ to guanosine residues, and has been used to monitor the secondary structure of RNA. However, we previously demonstrated large variations in the T1 accessibility of the theoretically unpaired G residues in the folded Ca.LSU intron RNA, which correlated with the tertiary structure of this ribozyme (26,27), proving that RNase T1 cleavage reflects not only the base pairing but also the tertiary structure of this folded RNA. In the folded Ca.LSU RNA, the exterior unpaired G residues are much more accessible to T1 than the interior unpaired Gs. Compared with the widely used free radical cleavage methodology, the larger T1 molecule has much less opportunity to reach the interior structure of a folded RNA and may be a more suitable structure probe for the exterior surface of the compactly folded intron, i.e. the globular structure of the large structural RNA. The decreased T1 sensitivity at many accessible G sites (some G sites are not cleaved even in the absence of Mg2+) (26), including theoretically unpaired Gs and paired Gs, correlates with compact folding of the ribozyme RNA, and a compactly folded RNA structure correlates with a smaller radius of gyration. Hence, we believe that the decreased T1 sensitivity at G sites indicates the compaction of the ribozyme RNA, though this evidence is indirect. The word ‘compaction’ is used hereafter in the text to simplify the description, and refers to nuclease protection rather than hydrodynamic measurement of the radius of RNA molecules.

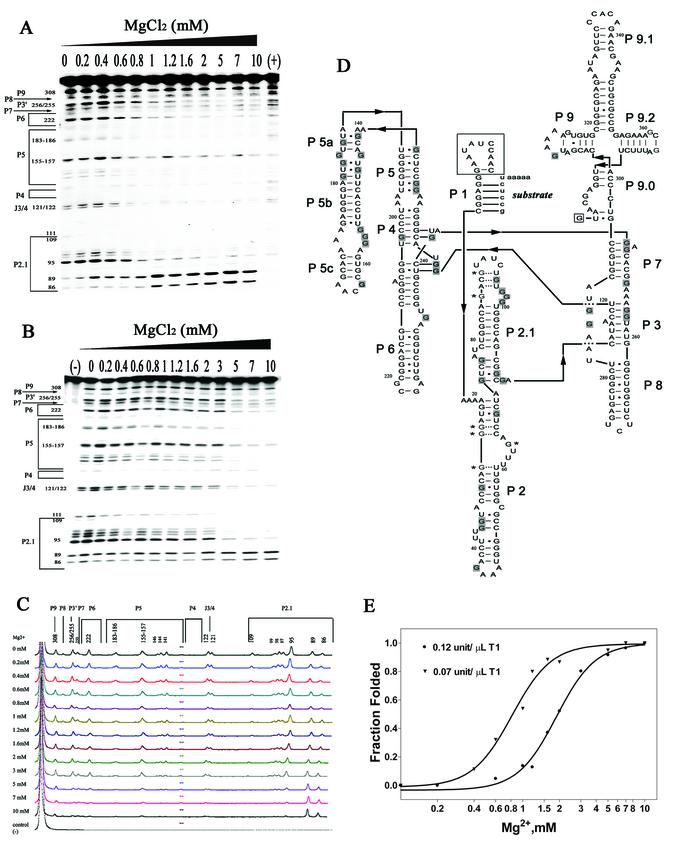

Two concentrations of T1, 0.07 and 0.12 U/µl, were used to monitor the effect of Mg2+ on the compact folding of the Ca.L-11 ribozyme (Fig. 2). Ribozyme RNA was pre-folded at various Mg2+ concentrations, and then cleaved by T1 for 1 min. The T1 accessibility of each G residue of the ribozyme RNA was reflected by the intensity of each corresponding cleaved fragment fractionated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels that were scanned and analyzed using the Typhoon 9200 variable scanner. We found that almost all of the well-defined T1-accessible G sites in the absence of Mg2+ are incrementally protected as the Mg2+ concentration increases, except for G86 and G89 in P2.1 and G25, G26, G27 and G64 in P2, which become more accessible, consistent with P2.1 and P2 folding in the exterior of the ribozyme and the secondary structure of these helices being altered upon the addition of magnesium (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

(Opposite) Mg2+-dependent compact folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme assayed by RNase T1 footprinting. The 5′-end-labeled Ca.L-11 RNA folded at the indicated concentrations of Mg2+ was cleaved by 0.07 U/µl (A) or 0.12 U/µl (B) of RNase T1. One representative gel for each T1 concentration is shown here; other gels resulting from multiple runs of the same samples to clearly visualize the band intensity of all the G sites are not shown. (C) Analysis of 0.12 U/µl of T1 accessibility when the ribozyme was folded under various magnesium concentrations. The band intensity profile of each lane on T1 footprinting gels that was scanned with Typhoon 9200 was obtained by using ImageQuant 5.2 software (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The result from 0.07 U/µl of T1 cleavage is not shown. (D) The illustrated secondary structure of Ca.L-11. The first 11 nt and the last ωG of the full intron that are absent from Ca.L-11 are boxed. Dashed lines indicate the base pairs that may not form. All the Mg2+-protected G residues (shaded) and sensitized Gs (marked by asterisks) are depicted in this secondary structure. (E) Compact folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme is dependent on Mg2+. Ffold versus [Mg2+] was fitted to the Hill equation Ffold = [Mg2+ ]n/(Mg1/2n + [Mg2+ ]n). The fraction folded was normalized by taking the observed intensities at 0 and 10 mM MgCl2 as unfolded and completely folded. The ribozyme is half-folded at an Mg1/2 of 1.89 ± 0.24 mM (filled circles) and 0.82 ± 0.13 mM (filled inverted triangles) for 0.12 and 0.07 U/µl of T1, respectively. The best fit line corresponds to an apparent cooperativity (n) of 2.8 Mg2+ ions.

Folding of the ribozyme RNA into the compact structure was thus measured by the overall decrease in the band intensity of all accessible Gs except for those becoming more exposed. Compaction at each Mg2+ concentration was reflected by the decreased T1 accessibility by considering the observed band intensities at 0 and 10 mM Mg2+ as non-compact and completely compact structures, respectively (Fig. 2E). When 0.07 U/µl of T1 was used, the Mg2+ concentration required for half-maximal protection (Mg1/2) is ∼0.8 mM; the maximal protection is achieved at Mg2+ ≥1.5 mM (Fig. 2A and E), at which concentration the ribozyme starts to efficiently catalyze substrate cleavage (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, when the T1 concentration was increased to 0.12 U/µl in each reaction, the monitored Mg2+-dependent compaction of the ribozyme RNA showed a transition equilibrium extremely close to that of kobs, with Mg1/2 of 2 mM, and maximal protection at an Mg2+ concentration ≥5 mM (Fig. 2B, C and E). The increase in the RNA cleavage with T1 concentration can be readily explained by the assumption that a more compact structure formed at higher Mg2+ concentrations is required to counter stronger digestion at higher T1 concentrations. Nevertheless, the Mg2+ Hill coefficient for both T1 concentrations is about 2.7, very close to the Hill coefficient of 3.1 for catalytic activity (Figs 2E and 1C). The similar equilibrium transition in catalysis and T1-monitored compaction of the ribozyme RNA versus Mg2+ concentrations suggests that the ribozyme may fold rapidly into the native structure without being trapped in the non-native tertiary intermediates that are commonly stabilized by Mg2+.

The rate of compact folding of Ca.L-11 at 1–10 mM Mg2+ was then measured by 1-min T1 cleavage after the ribozyme was folded at 37°C for between 0 and 20 min (Fig. 3). We found that the maximal protection at each Mg2+ concentration was observed without pre-incubation to allow RNA folding (Fig. 3, lanes ‘0’); no enhanced protection was observed after pre-incubation for up to 20 min (Fig. 3, other lanes). Meanwhile, differential protection at different Mg2+ concentrations similar to that shown in Figure 2 was clearly demonstrated in the same experiment, with maximal protection achieved at 5 and 10 mM Mg2+ and less protection at 2 and 1 mM Mg2+. At each Mg2+ concentration, simultaneous addition of RNase T1 for RNA cleavage and of Mg2+ to initiate RNA folding resulted in minimal accessibility of the ribozyme RNA structures (Fig. 3, lanes ‘0’) as compared with RNA samples pre-folded for up to 20 min. We thus conclude that Ca.L-11 reaches its compaction equilibrium rapidly in the presence of Mg2+ before significant T1 cleavage occurs. The compaction is estimated to be complete within a subsecond time scale. These results are consistent with the recent report that overall compaction and global shape change during folding of Tetrahymena intron RNA are largely completed within 1 s (28), and tertiary folding of a small bacterial group I ribozyme occurs at the millisecond time scale (29). The differential protection exerted by various Mg2+ concentrations may represent the formation of RNA structures with different levels of compaction, and the catalytic capability of these different structures varies greatly, as shown in Figure 1C.

Kinetics of native folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme are not interfered with by Mg2+-stabilized intermediates

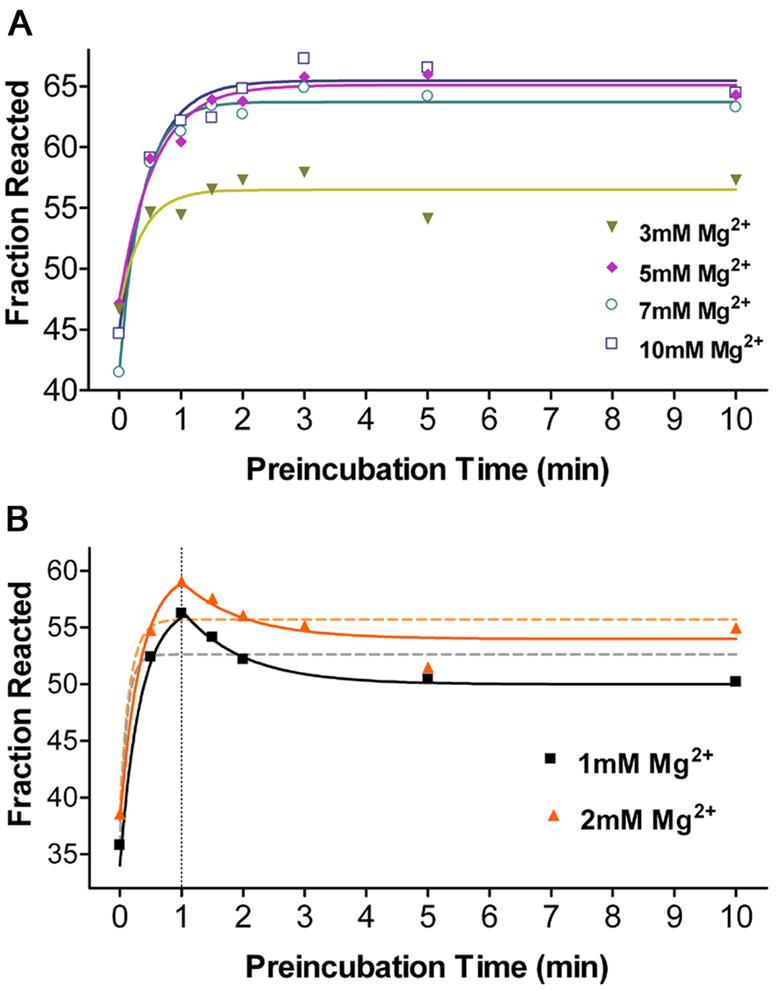

The rate of folding of Ca.L-11 into its catalytically active structure (koverall) was then measured by the fraction of substrate cleaved during a 1-min incubation in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+, after the ribozyme was allowed to pre-fold at various Mg2+ concentrations (21). Accumulation of the correctly folded ribozyme molecules during pre-folding is reflected by an increase in the level of the released product during 1-min ribozyme-catalyzed cleavage. As shown in Figure 4A, folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme to the catalytically active structures at 3–10 mM Mg2+ required a much longer time than compaction of the ribozyme RNA, with a rate constant of ∼1–2 min–1. No obvious differences in koverall were evident at different magnesium concentrations, suggesting the absence of magnesium-stabilized kinetic traps in the pathway of Ca.L-11 folding. This magnesium response of Ca.L-11 significantly differs from that of its Tetrahymena ribozyme counterpart, L-21 ScaI, whose native folding rate koverall is markedly reduced by higher magnesium concentrations. As compared with L-21 ScaI, native folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme at 10 mM Mg2+ is ∼32-fold faster (21). Folding data at Mg2+ concentrations ≥3 mM fit to the single exponential curve very well, suggesting the presence of a single folding pathway for most RNA becoming the catalytically active structure. However, the data at 1 or 2 mM Mg2+ do not fit to the single exponential curve (Fig. 4B), suggesting a different folding mechanism that may relate to the less compact structures at these magnesium concentrations. Furthermore, the ribozyme RNA reached the maximal catalytic activity after 1-min pre-incubation at low Mg2+ concentrations, and longer pre-incubation resulted in slightly decreased activity until 5 min (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that a small fraction of Ca.L-11 RNA folded at low Mg2+ concentrations might be converted into misfolded structure(s), resulting in reduction of the observed ribozyme activity.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of overall folding (koverall) of Ca.L-11 into its catalytically active structures measured by 1-min cleavage at 10 mM Mg2+. Substrate cleavage was initiated by addition of reaction mixture after folding for the indicated periods of time, which brought [Mg2+] to 10 mM. Folding data at higher [Mg2+] fit to the single exponential curve (A), while the data at lower [Mg2+] was best fit to curves drawn manually (solid lines), with the single exponential fit indicated by dashed lines (B). Two parallel experiments were done for each concentration. koverall obtained from single exponential fit at each Mg2+ concentration is 9.352 ± 32.04 min–1 at 1 mM, 6.534 ± 10.19 min–1 at 2 mM, 2.721 ± 1.188 min–1 at 3 mM, 1.747 ± 0.4002 min–1 at 5 mM, 2.767 ± 0.5096 min–1 at 7 mM, and 2.054 ± 0.3973 min–1 at 10 mM. Baseline (cleavage without pre-folding) and span (maximal increased cleavage with pre-folding) at 10 mM are 44.91 ± 1.400 and 20.55 ± 1.533%.

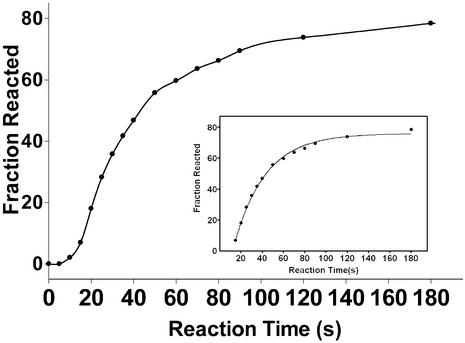

The rate of the initial burst of product from Ca.L-11 catalysis should reflect the rate of ribozyme folding into its catalytically active structure for two reasons. First, Ca.L-11 binds to its substrate very tightly, with a Kd of 4 nM (unpublished data), so turnover is minimized during the first minute of catalysis. Secondly, the rate of the chemical reaction of group I intron catalysis is much faster than ribozyme folding (18,21). When 1.5-fold substrate relative to the ribozyme RNA was present in the reactions, >40% of the substrate was cleaved in 1 min at 10 mM Mg2+, suggesting that >60% of the ribozyme is folded into the catalytically active structure within 1 min; the 62% substrate cleavage after 1 min pre-folding at 10 mM Mg2+ suggests that ∼90% of the ribozyme folded into the catalytically active structure within 2 min (Fig. 4B). We then increase the ratio of ribozyme/substrate to 1; the initial product burst was measured by taking samples at intervals of 5–10 s until 90 s (Fig. 5). We found that 60% of the substrate was cleaved in 1 min, in good agreement with the data obtained in the presence of 1.5-fold substrate. The product burst after 15 s fits to a first exponential curve with a rate constant of 0.04 s–1, which is close to the koverall of ∼2.0 min–1. One reason for the lack of product release in the first 15 s could be the minimal time required to increase the solution temperature to 37°C from 0°C (ice-cold). GTP and substrate binding may also contribute to the lag of product burst. Nevertheless, these data demonstrate that ∼90% of Ca.L-11 RNA may fold into its native structure at 10 mM Mg2+ via a single folding pathway with a rate constant of ∼2.0 min–1, and no other folding pathways with slower kinetics are evident.

Figure 5.

Folding of Ca.L-11 analyzed by initial product burst. The fraction of the product versus reaction time is dot-connected, and that after 15 s is best fit to the equation, Fract = Fracmax[1 – e–k(t–t0)] + Fract0 (t0 = 15 s) (insert), that yields a rate constant of 0.04234 ± 0.00047 s–1.

DISCUSSION

Concerted folding of Ca.L-11 into the catalytically active structure

The folding mechanism of a functional RNA into its active structure becomes an essential question in RNA biology. Folding of the well-studied Tetrahymena ribozyme follows the kinetic partitioning mechanism. Only a small fraction (∼12%) of the ribozyme molecules fold rapidly to the native state, whereas the remaining fraction is kinetically trapped in the stable non-native state(s) with low free energy (3). Conversion of such RNA intermediate(s) into the native structure requires dissociation of some non-native interactions, which is energetically unfavorable, and thus is kinetically slow (up to hours) (17,30). It is demonstrated that the 12% of RNA molecules with native structure are formed through two pathways with rate constants of 1 s–1 and 1 min–1, respectively. The strong magnesium dependence and uniform transition equilibrium of both the compaction and kobs of a Candida intron-derived trans-acting ribozyme suggest a rapid folding of this ribozyme and the lack of magnesium-stabilized kinetic traps. Surprisingly, ∼90% of Ca.L-11 RNA molecules fold into the catalytically active structure at 10 mM Mg2+ through a single pathway with a rate constant of ∼2 min–1, as was demonstrated by overall folding (koverall) and initial product burst (kburst). In contrast to Tetrahymena ribozyme (20), folding at lower Mg2+ concentrations does not increase the folding rate of this ribozyme, and there is no evidence for the presence of a slower folding pathway involving trapped intermediates. Therefore, folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme into the catalytically active structure is concerted and fast, which differs significantly from that of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. This difference may be attributed to the difference in the structure of P5abc among these introns; L5c of the Tetrahymena ribozyme has been proven to interact with L2 to lower the folding rate (23), whereas the different P5abc structure in Candida intron may eliminate or weaken such an interaction. Consistent with this model is the finding that mutations disrupting the interaction between L5b and its cognate tetraloop receptor enable the Tetrahymena ribozyme to fold more rapidly without obvious kinetic traps (24).

However, this conclusion does not exclude the possibility that kinetic traps exist at higher magnesium concentrations or during folding of cis-acting Candida intron for self-splicing, whose catalysis includes two consecutive transesterification reactions. The inhibition of self-splicing of the Candida intron by pre-folding in magnesium (26) suggests the presence of Mg2+-stabilized kinetic trap(s) after the first transesterification reaction, because there is no such trap in folding and catalysis of the Ca.L-11 ribozyme, which mimics that first reaction. The role of exon sequences in ribozyme folding in precursor RNA cannot be excluded, however.

Folding of Ca.L-11 ribozyme is initiated by a rapid RNA compaction and followed by a conformational searching

Compaction of the Tetrahymena ribozyme into a tightly packaged structure prior to the stable formation of tertiary contacts occurs within 1 s (28). Using RNase T1 footprinting, we found that the Ca.L-11 ribozyme reaches its compaction equilibrium in a subsecond time scale before significant RNase T1 cleavage occurs. Mg2+-dependent compaction equilibrium determined by an adequate amount of T1 agrees very well with the Mg2+-dependent increase in kobs, suggesting that the compact structure of Ca.L-11 RNA is the primary determinant of the native folding of this ribozyme. However, we found that this ribozyme folds into the catalytically active structure much more slowly than compaction, with a rate constant of 2 min–1. These results suggests that considerable time is required to form the native tertiary contacts of the ribozyme after Ca.L-11 RNA is compactly folded, probably involving additional base pairing and local structural rearrangement, termed conformational searching (14).

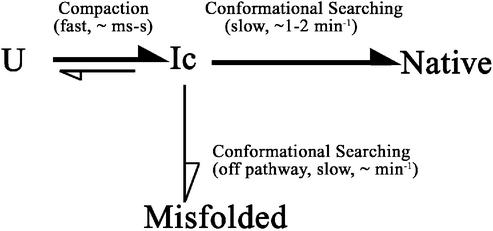

A simplified scheme for folding of the Ca.L-11 ribozyme is proposed in Figure 6. Upon the addition of magnesium, the unfolded Ca.L-11 RNA (U) formed in Tris buffer first undergoes a very rapid compaction (milliseconds to seconds) to form the compact intermediates (Ic), which then undergo a slower (minutes) conformational searching for native contacts to form the catalytically active structure. Our results demonstrate that the compaction rate may not be affected by Mg2+, but the compaction equilibrium is strongly dependent on Mg2+, with complete compaction occurring at Mg2+ ≥5 mM, and half-maximal compaction occurring at ∼2 mM Mg2+. The equilibrium for the subsequent conformational searching may also depend on Mg2+. The loose globular structure of Ca.L-11 RNA formed at lower Mg2+ concentrations might confer on the ribozyme RNA more flexibility in forming tertiary contacts, allowing some non-native tertiary interactions that are responsible for the misfolded structure(s) and the modestly reduced activity after 1 min pre-folding. We acknowledge the formal possibility that the ‘order’ of folding events might be altered at low magnesium concentrations, allowing the fast formation of some non-native structures that hinder the native folding.

Figure 6.

Schemes for self-folding of Ca.L-11.

This folding scheme is similar to the trap-free folding of bI5 that requires CBP2 protein to capture a collapsed structure (Ic-like) to its active structure (12). The low Gibbs free energy of the Ca.LSU intron, indicated by the high G + C content of this ribozyme (58% versus 22% of bI5 core), may eliminate the requirement for a binding protein to stabilize the native structure of this ribozyme. Hence, folding of Ca.L-11 represents another strategy in folding of structural RNA. The concerted and fast folding of this ribozyme into the catalytically active structure provides an excellent system to study the details of conformational searching, ion binding and the role of productive intermediates, without the experimental complication of accumulation of most of the RNA in a long-lived misfolded state.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Xiang-dong Fu (UCSD) and Sarah Woodson (Johns Hopkins University) for their critical reading of the manuscript. This study is supported by the NSFC through grants 30040033 and 30170213 and by Wuhan University through grant 0000028 (Y.Z.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Doudna J.A. and Cech,T.R. (2002) The chemical repertoire of natural ribozymes. Nature, 418, 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narlikar G.J. and Herschlag,D. (1997) Mechanistic aspects of enzymatic catalysis: lessons from comparison of RNA and protein enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 66, 19–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thirumalai D., Lee,N., Woodson,S.A. and Klimov,D.K. (2001) Early events in RNA folding. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem., 52, 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cech T.R. (1990) Self-splicing of group I introns. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 59, 543–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Ahsen U., Davies,J. and Schroeder,R. (1991) Antibiotic inhibition of group I ribozyme function. Nature, 353, 368–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weeks K.M. and Cech,T.R. (1995) Protein facilitation of group I splicing by assembly of the catalytic core and the 5-prime splice site domain. Cell, 82, 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Horst G. and Tabak,H.F. (1985) Self-splicing of yeast mitochondrial ribosomal and messenger RNA precursors. Cell, 40, 759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercure S., Montplaisir,S. and Lemay,G. (1993) Correlation between the presence of a self-splicing intron in the 25S rDNA of C.albicans and strains susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 6020–6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michel F. and Westhof,E. (1990) Modelling of the three-dimensional architecture of group I catalytic introns based on comparative sequence analysis. J. Mol. Biol., 216, 585–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caprara M.G., Lehnert,V., Lambowitz,A.M. and Westhof,E. (1996) A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase recognizes a conserved tRNA-like structural motif in the group I intron catalytic core. Cell, 87, 1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caprara M.G., Mohr,G. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1996) A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase protein induces tertiary folding of the group I intron catalytic core. J. Mol. Biol., 257, 512–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchmueller K., Webb,A.E., Richardson,D.A. and Weeks,K.M. (2000) A collapsed non-native RNA folding state. Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 362–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb A.E. and Weeks,K.M. (2001) A collapsed state functions to self-chaperone RNA folding into a native ribonucleoprotein complex. Nature Struct. Biol., 8, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Treiber D.K. and Williamson,J.R. (2001) Beyond kinetic traps in RNA folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 11, 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celander D.W. and Cech,T.R. (1991) Visualizing the higher order folding of a catalytic RNA molecule. Science, 251, 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sclavi B., Sullivan,M., Chance,M.R., Brenowitz,M. and Woodson,S.A. (1998) RNA folding at millisecond intervals by synchrotron hydroxyl radical footprinting. Science, 279, 1940–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan J., Thirumalai,D. and Woodson,S.A. (1999) Magnesium-dependent folding of self-splicing RNA: exploring the link between cooperativity, thermodynamics and kinetics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 6149–6154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhuang X.W., Bartley,L.E., Babcock,H.P., Russell,R., Ha,T., Herschlag,D. and Chu,S. (2000) A single-molecule study of RNA catalysis and folding. Science, 288, 2048–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan J., Thirumalai,D. and Woodson,S.A. (1997) Folding of RNA involves parallel pathways. J. Mol. Biol., 273, 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rook S.M., Treiber,D.K. and Williamson,J.R. (1999) An optimal Mg2+ concentration for kinetic folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 12471–12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell R. and Herschlag,D. (1999) New pathways in folding of the Tetrahymena group I RNA enzyme. J. Mol. Biol., 291, 1155–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treiber D.K., Rook,M.S., Zarrinkar,P.P. and Williamson,J.R. (1998) Kinetic intermediates trapped by native interactions in RNA folding. Science, 279, 1943–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan J., Deras,M.L. and Woodson,S.A. (2000) Fast folding of a ribozyme by stabilizing core interactions: evidence for multiple folding pathways in RNA. J. Mol. Biol., 296, 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treiber D.K. and Williamson,J.R. (2001) Concerted kinetic folding of a multidomain ribozyme with a disrupted loop–receptor interaction. J. Mol. Biol., 305, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang X.W., Pan,T. and Sosnick,T.R. (1999) Mg2+-dependent folding of a large ribozyme without kinetic traps. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 1091–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y. and Leibowitz,M.J. (2001) Folding of the group I intron ribozyme from the 26S rRNA gene of Candida albicans. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 2644–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y., Li,Z.J., Pilch,D.S. and Leibowitz,M.J. (2002) Pentamidine inhibits catalytic activity of group I intron Ca.LSU by altering RNA folding. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 2961–2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell R., Millett,L.S., Tate,M.W., Kwok,L.W., Nakatani,B., Gruner,S.M., Mochrie,V.P., Dniach,S., Herschlag,D. and Pollack,L. (2002) Rapid compaction during RNA folding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 4266–4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rangan P., Masquida,B., Westhof,E. and Woodson,S.A. (2003) Assembly of core helices and rapid tertiary folding of a small bacterial group I ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 1574–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan J. and Woodson,S.A. (1998) Folding intermediates of a self-splicing RNA: mispairing of the catalytic core. J. Mol. Biol., 280, 597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]