Abstract

The coupling of proton chemistry with redox reactions is important in many enzymes and is central to energy transduction in biology. However, the mechanistic details are poorly understood. Here, we have studied tyrosine oxidation, a reaction in which the removal of one electron from the amino acid is linked to the release of its phenolic proton. Using the unique photochemical properties of photosystem II, it was possible to oxidize the tyrosine at 1.8 K, a temperature at which proton and protein motions are limited. The state formed was detected by high magnetic field EPR as a high-energy radical intermediate trapped in an unprecedentedly electropositive environment. Warming of the protein allows this state to convert to a relaxed, stable form of the radical. The relaxation event occurs at 77 K and seems to involve proton migration and only a very limited movement of the protein. These reactions represent a stabilization process that prevents the back-reaction and determines the reactivity of the radical.

Redox active tyrosines in enzymes exhibit a diverse range of chemical properties, with radical lifetimes ranging from microseconds to days (1). Tyrosine oxidation results in a pKa shift of >12 units so it is expected that the loss of the electron is accompanied by deprotonation (1). The protein controls the reactivity of the tyrosine and its radical through modulation of the proton transfer reactions that are coupled with electron transfer (1-3).

One of the most intriguing examples of the influence of the protein on the properties of tyrosyl radicals is found in the water-oxidizing enzyme of photosynthesis, photosystem II (PSII; refs. 2 and 3). This enzyme contains two symmetrically positioned redox active tyrosyl residues, TyrD and TyrZ, one on each subunit of the heterodimeric core of the photosynthetic reaction center (2-6), a system that seems to have evolved from a homodimeric protein ancestor in which both redox active tyrosines had identical properties (7).

The function and chemical properties of the two tyrosyl radicals are quite

distinct.  exhibits

high stability (days in the intact enzyme) and has a relatively low redox

potential (2,

3). Although TyrD is

not essential for enzyme activity

(5,

6), its redox poises the Mn

cluster (8) and may

electrostatically tune the adjacent chlorophyll cation radical

(9). The other PSII tyrosyl

radical,

exhibits

high stability (days in the intact enzyme) and has a relatively low redox

potential (2,

3). Although TyrD is

not essential for enzyme activity

(5,

6), its redox poises the Mn

cluster (8) and may

electrostatically tune the adjacent chlorophyll cation radical

(9). The other PSII tyrosyl

radical,  , is

short-lived (tens of microseconds to a few milliseconds) in the functional

enzyme, is kinetically competent in water oxidation, and has a redox potential

estimated to be from 0.95 to 1.1 V

(2,

3). In addition,

, is

short-lived (tens of microseconds to a few milliseconds) in the functional

enzyme, is kinetically competent in water oxidation, and has a redox potential

estimated to be from 0.95 to 1.1 V

(2,

3). In addition,

is close to the Mn

cluster, and in some models

is close to the Mn

cluster, and in some models

chemistry is seen as

being directly involved in water oxidation

(10).

chemistry is seen as

being directly involved in water oxidation

(10).

The tyrosyl radicals of PSII are especially attractive as an experimental

system, not only because of the interest in comparing

and

and

, but also (because

of the unique properties of the photochemical reaction center) because it is

possible to study radical formation with rapid kinetics

(2,

3,

11) and, for TyrD

at least, at cryogenic temperatures

(12). Thus,

, but also (because

of the unique properties of the photochemical reaction center) because it is

possible to study radical formation with rapid kinetics

(2,

3,

11) and, for TyrD

at least, at cryogenic temperatures

(12). Thus,

formation is

potentially a rare, possibly unique, case in which proton-coupled electron

transfer can be studied at cryogenic temperatures, conditions under which

protein and proton motions are greatly restricted, thus allowing the trapping

of unstable intermediate radical states before the occurrence of

temperature-dependent relaxation processes.

formation is

potentially a rare, possibly unique, case in which proton-coupled electron

transfer can be studied at cryogenic temperatures, conditions under which

protein and proton motions are greatly restricted, thus allowing the trapping

of unstable intermediate radical states before the occurrence of

temperature-dependent relaxation processes.

Here, we have looked for such intermediate states by using the highest

resolution possible with high-frequency high magnetic-field EPR (HFEPR). EPR

spectra of tyrosyl radicals obtained with 9-GHz microwaves are dominated by

proton hyperfine couplings that are determined by the magnetic interaction

between the unpaired electron spin and nearby proton nuclei. By contrast, when

285-GHz microwaves are used, the EPR spectra of tyrosyl radicals are dominated

by the resolved anisotropy in the g-tensor

(13–15).

The three components of the g-tensor define the interaction energy of

the unpaired electron spin of the radical with the applied magnetic field and

is very similar to the chemical shift in NMR

(Fig. 1). We have previously

demonstrated that the g-tensor component along the phenolic  bond, gx, of tyrosyl radicals

(16) is a particularly

effective measure of their electrostatic environment

(13,

14).

bond, gx, of tyrosyl radicals

(16) is a particularly

effective measure of their electrostatic environment

(13,

14).

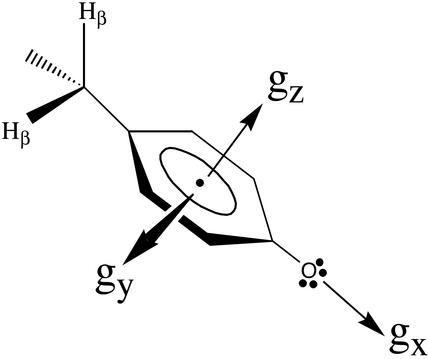

Fig. 1.

The orientation of g-tensor with respect to the molecular frame of

a tyrosyl radical: the gx is directed along

phenolic  bond, gz perpendicular to the

phenyl ring plane, and gy mutually perpendicular

to the other two components. When the magnetic field is applied along the

bond, gz perpendicular to the

phenyl ring plane, and gy mutually perpendicular

to the other two components. When the magnetic field is applied along the

bond (gx) direction, a peak at the

magnetic field corresponding to the gx value is

observed in the high-field EPR spectrum and likewise for

gy and gz.

bond (gx) direction, a peak at the

magnetic field corresponding to the gx value is

observed in the high-field EPR spectrum and likewise for

gy and gz.

Materials and Methods

The PSII-enriched membranes from spinach were prepared essentially by the method of Berthold, Babcock, and Yocum (17). Mn was depleted from PSII by treating with NH2OH as reported (11) but maintained in darkness. Darkness was maintained for all subsequent sample manipulations. Before use, the pH of the PSII samples was adjusted by resuspension of the sample in Tricine/NaOH (pH 8.7) buffer (40 mM). The final Chl concentration for EPR measurements was 4 mg of Chl per ml.

TyrD is known to be hydrogen-bonded to a nearby histidine (His-189 of the D2 subunit in Synechocystis 6803). The structures and energies of such a tyrosine-histidine hydrogen-bonded pair were determined from geometry optimization of a p-cresol-imidazole supramolecular complex by using the program gaussian-94 (18) using the BLY3P (19-21) method and 6+31(d,p) and 6+311(2d,p) basis sets. Similar calculations have been reported on the phenol-imidazole complex (22). The structures and hydrogen-bonding energies of the initial and final states were from global optimizations. For the intermediate states formed immediately after electron transfer but before relaxation, the structure and hydrogen-bonding energies were calculated by restricting the position of the pair to the geometry before tyrosine oxidation. In all cases, the calculation showed that the ring planes remained coplanar.

The 9-GHz EPR spectra were recorded with a Bruker (Rheinstetten, Germany) ESP 300 spectrometer equipped with an Oxford Instruments (Oxon, U.K.) cryostat cooled with liquid helium. Illumination at 5–15 K was carried out in the EPR cavity by using an 800-W tungsten lamp filtered through 5 cm water and three infrared cut-off filters. The high-field EPR spectrometer has been described (23). Illumination at 1.8–15 K was done by using a 20-W quartz halogen lamp directed at the microwave output waveguide window. The light was carried via the microwave waveguide to the sample in the cryostat.

Results

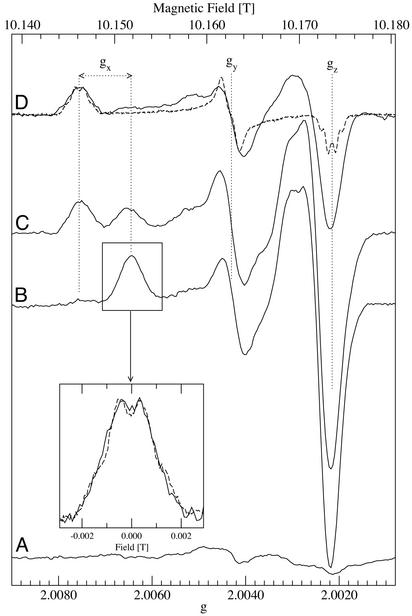

Fig. 2

B–D shows that the HFEPR spectra of the

radical

photo-generated at liquid helium and physiological temperatures are strikingly

different from each other, even though the conventional 9-GHz EPR spectra are

indistinguishable (Fig. 3; ref.

12). The most obvious

difference in the high-field spectra is that the

gx feature in the low-temperature

radical

photo-generated at liquid helium and physiological temperatures are strikingly

different from each other, even though the conventional 9-GHz EPR spectra are

indistinguishable (Fig. 3; ref.

12). The most obvious

difference in the high-field spectra is that the

gx feature in the low-temperature

spectrum is at a

higher field position (Fig.

2B) compared with that of the

spectrum is at a

higher field position (Fig.

2B) compared with that of the

generated at

physiological temperature (Fig.

2D).

generated at

physiological temperature (Fig.

2D).

Fig. 2.

High-field 285-GHz EPR spectra of the

generated in

Mn-depleted PSII at low temperatures. (A) Baseline spectrum before

illumination. (B) After illumination at 1.8 K. (C) Same

sample warmed to 77 K for 10 min. (D) Solid line, same sample warmed

to 200 K for 1 min; dashed line, similar sample

(24) with the radical obtained

at physiological temperatures. Spectra were obtained at 285 GHz at 4.2 K and

were normalized averages of 8–16 scans obtained with a field modulation

of 20 G. The dotted black lines from right to left are positioned at

g-values of 2.00215, 2.00430, 2.00645, and 2.00756. (Inset)

Comparison of the gx region of radical obtained

after 1.8-K illumination (10 G modulation, solid-line) and radical obtained at

physiological temperatures (3 G modulation, dashed line, also shown in its

entirety in D).

generated in

Mn-depleted PSII at low temperatures. (A) Baseline spectrum before

illumination. (B) After illumination at 1.8 K. (C) Same

sample warmed to 77 K for 10 min. (D) Solid line, same sample warmed

to 200 K for 1 min; dashed line, similar sample

(24) with the radical obtained

at physiological temperatures. Spectra were obtained at 285 GHz at 4.2 K and

were normalized averages of 8–16 scans obtained with a field modulation

of 20 G. The dotted black lines from right to left are positioned at

g-values of 2.00215, 2.00430, 2.00645, and 2.00756. (Inset)

Comparison of the gx region of radical obtained

after 1.8-K illumination (10 G modulation, solid-line) and radical obtained at

physiological temperatures (3 G modulation, dashed line, also shown in its

entirety in D).

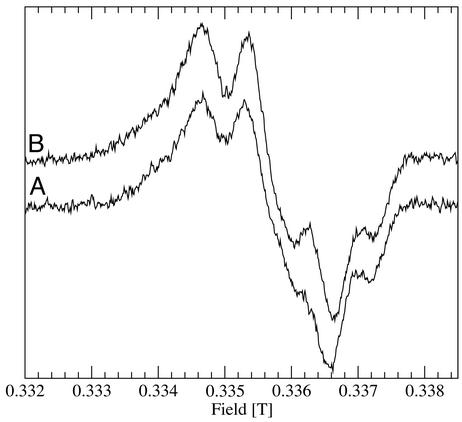

Fig. 3.

Nine-gigahertz EPR spectra of

photo-generated in

Mn-depleted PSII at 4 K (A) and after warming to 200 K (B).

Both spectra were obtained at 4 K.

photo-generated in

Mn-depleted PSII at 4 K (A) and after warming to 200 K (B).

Both spectra were obtained at 4 K.

When the liquid helium temperature-illuminated sample was incubated for 10

min at 77 K in darkness, the gx feature in the

high-field EPR spectrum decreased in amplitude, the

gy (and less clearly the

gz) feature did not change amplitude, and an

additional signal appeared with the g-values corresponding to that of

the normal  as

generated at physiological temperatures

(Fig. 2C). Clearly a

partial conversion from the low-temperature spectrum to the physiological

temperature spectrum occurred. Further incubation in darkness at 200 K for 1

min resulted in the disappearance of the low-temperature

as

generated at physiological temperatures

(Fig. 2C). Clearly a

partial conversion from the low-temperature spectrum to the physiological

temperature spectrum occurred. Further incubation in darkness at 200 K for 1

min resulted in the disappearance of the low-temperature

signal, with the

ambient temperature-type spectrum left in its place

(Fig. 2D).

signal, with the

ambient temperature-type spectrum left in its place

(Fig. 2D).

By varying the 77-K incubation time, it was possible to trap different

proportions of the low temperature and physiological-type

signals. The

half-conversion time was estimated to be ≈7 min at 77 K. No broadening

occurred in any of the spectral features of the two forms of the signals nor

were signals observed with intermediate g-values. These observations

indicate that warming results in the conversion of one well-defined tyrosyl

radical species into another.

signals. The

half-conversion time was estimated to be ≈7 min at 77 K. No broadening

occurred in any of the spectral features of the two forms of the signals nor

were signals observed with intermediate g-values. These observations

indicate that warming results in the conversion of one well-defined tyrosyl

radical species into another.

The partially resolved fine-structure seen in both the 9-GHz spectra (Fig. 3) and the high-field spectra of the gx region recorded under high-resolution conditions (Fig. 2 Inset) arises from magnetic interactions between nearby protons and the unpaired electron. The largest of these hyperfine couplings is due to a β-methylene proton (Fig. 1) and is determined by the relative orientation of this proton with respect to the tyrosyl ring (≈48°; ref. 24). The fact that the hyperfine structure is identical whether the radical was generated at 1.8 K or at physiological temperatures indicates that the angular orientation of the tyrosyl ring relative to the methylene protons is the same in both cases. Again, the data indicate two well-defined states and a step-wise change from one to the other.

The g-values of the tyrosyl radicals were determined by computer

simulation. The gx-value for the cryogenically

generated radical was 2.00643 compared with 2.00756 for tyrosyl radical

generated at physiological temperatures

(25). The difference in

gx values reflects differences in the

electrostatic environment of the two radicals. In the literature, the

gx-values for tyrosyl radicals range from 2.0065,

due a strong hydrogen-bond

(16), to 2.0094, in a nonpolar

environment (15). Thus, the

gx-value of the low-temperature

reported here is the

lowest reported for a tyrosyl radical, indicating the most electropositive

environment yet encountered

(13–15,

23)

reported here is the

lowest reported for a tyrosyl radical, indicating the most electropositive

environment yet encountered

(13–15,

23)

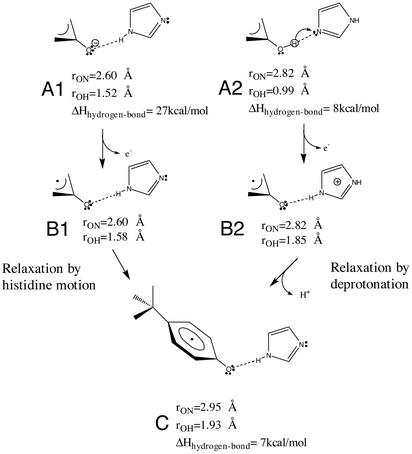

We carried out hybrid density-functional Hartree–Fock calculations on the p-cresol-imidazole molecular complex to obtain insights into the structure of the intermediate states and the relaxation events associated with two different models for the reactions detected here. The models and the results are illustrated in Fig. 4, and they are described in detail in Discussion.

Fig. 4.

Structural model for the stable tyrosyl radical in PSII and two possible

reaction pathways for its formation via strained intermediate states. The

scheme shows structures for the reduced state (structures A1 and

A2), the intermediate state (B1 and B2), and the

final relaxed state (C). The pathway on the right is the

proton-coupled electron transfer model, and it starts and ends with a neutral

pair: TyrD-His (A2) and

(C), respectively, with the latter having lost both an electron and a

proton. The high-energy intermediate state (B2) results from the

close proximity of the cationic histidine residue to the neutral radical.

Relaxation of this state (B2) is dominated by the deprotonation of

the imidazole ring, leading to a neutral state with hydrogen-bonding that is

energetically favorable (C). The pure electron transfer is shown on

the left; the starting point is the TyrD-His pair, which has a very

short 1.52-Å hydrogen-bonding distance due to negative charge on the

tyrosine residue (A1). Oxidation at liquid helium temperature results

in a neutral tyrosyl radical with a very short hydrogen bond (1.58 Å),

resulting in an energetically highly strained state (B1). The

relaxation in this case is attributed to a separation of the neutral

(C), respectively, with the latter having lost both an electron and a

proton. The high-energy intermediate state (B2) results from the

close proximity of the cationic histidine residue to the neutral radical.

Relaxation of this state (B2) is dominated by the deprotonation of

the imidazole ring, leading to a neutral state with hydrogen-bonding that is

energetically favorable (C). The pure electron transfer is shown on

the left; the starting point is the TyrD-His pair, which has a very

short 1.52-Å hydrogen-bonding distance due to negative charge on the

tyrosine residue (A1). Oxidation at liquid helium temperature results

in a neutral tyrosyl radical with a very short hydrogen bond (1.58 Å),

resulting in an energetically highly strained state (B1). The

relaxation in this case is attributed to a separation of the neutral

pair (O

to N distance changing from 2.60 to 2.95 Å), allowing for the

lengthening of the compressed hydrogen bond to form the final stable state

(C).

pair (O

to N distance changing from 2.60 to 2.95 Å), allowing for the

lengthening of the compressed hydrogen bond to form the final stable state

(C).

It should be noted that the HFEPR spectra also contained contributions from

a narrow radical centered just above the free electron g-value

(ge = 2.00232). This radical arose from a

fraction of centers in which β-carotene is oxidized instead of

TyrD (12,

26,

27). When the sample

temperature was raised, a chlorophyll cation radical replaced the

β-carotene due to a temperature-dependent electron transfer reaction

(26) and was responsible for

small changes around the free electron region

(27). We have shown earlier

that a brief intense illumination results in a high yield of

whereas longer

illumination results in carotene radical formation

(12). The 9-GHz spectra were

obtained by using illumination conditions to avoid β-carotene radical

formation. Because of geometric limitations, formation of carotene radical in

a fraction of the centers could not be avoided in the HFEPR experiment.

whereas longer

illumination results in carotene radical formation

(12). The 9-GHz spectra were

obtained by using illumination conditions to avoid β-carotene radical

formation. Because of geometric limitations, formation of carotene radical in

a fraction of the centers could not be avoided in the HFEPR experiment.

Discussion

An intermediate state in

oxidation has been

trapped by generating the radical at liquid helium temperatures by using the

unique photochemical properties of the PSII reaction center. This state is

characterized by a very electropositive environment and can be considered as a

high-energy transition state. On warming to 77 K, this electropositive

environment changes and becomes indistinguishable from that seen when

oxidation has been

trapped by generating the radical at liquid helium temperatures by using the

unique photochemical properties of the PSII reaction center. This state is

characterized by a very electropositive environment and can be considered as a

high-energy transition state. On warming to 77 K, this electropositive

environment changes and becomes indistinguishable from that seen when

is formed at

physiological temperatures. The relaxation process seems to involve a

single-step phenomenon between two discrete states. In what follows, we

discuss the nature of the relaxation event, taking into account insights

gained from molecular orbital calculations.

is formed at

physiological temperatures. The relaxation process seems to involve a

single-step phenomenon between two discrete states. In what follows, we

discuss the nature of the relaxation event, taking into account insights

gained from molecular orbital calculations.

From considerations of (i) the amino acid sequence and the protein

folding model based on the structure of the purple bacterial reaction center,

(ii) site-directed mutagenesis, and (iii) spectroscopic

studies, it seems very likely that

is hydrogen-bonded

by His-189 of the same protein subunit (D2; refs.

2 and

3). Thus, discussion of

electron transfer and the associated protonation changes in this system

minimally involves both the TyrD itself and His-189, its

hydrogen-bonding partner.

is hydrogen-bonded

by His-189 of the same protein subunit (D2; refs.

2 and

3). Thus, discussion of

electron transfer and the associated protonation changes in this system

minimally involves both the TyrD itself and His-189, its

hydrogen-bonding partner.

In previous work, we have invoked two specific models to describe the unexpected submicrosecond kinetics and low-temperature chemistry of TyrD (11, 12): (i) proton-coupled electron transfer (Fig. 4, right branch) and (ii) pure electron transfer (Fig. 4, left branch). The evidence described here for a discrete intermediate state formed immediately after electron transfer can be incorporated into these models.

The hybrid density-functional Hartree–Fock calculations on the

p-cresol-imidazole molecular complex showed that, for the pure

electron transfer model, the neutral

intermediate has an extremely short hydrogen-bonding distance

(Fig. 4B1), arising

from a very strong hydrogen-bond interaction between the anionic tyrosine and

neutral histidine (Fig.

4A1). The relaxation of the strained neutral

intermediate has an extremely short hydrogen-bonding distance

(Fig. 4B1), arising

from a very strong hydrogen-bond interaction between the anionic tyrosine and

neutral histidine (Fig.

4A1). The relaxation of the strained neutral

intermediate requires an increase in distance of 0.35 Å and a rotation

of 5° in the hydrogen-bonding geometry.

intermediate requires an increase in distance of 0.35 Å and a rotation

of 5° in the hydrogen-bonding geometry.

In contrast, the proton-coupled electron transfer pathway starting from the

reduced neutral state (Fig.

4A2) involves a small proton motion (0.9 Å) from

the tyrosine to the histidine resulting in an intermediate that consists of

the  that is

hydrogen-bonded by a histidinyl cation

(Fig. 4B2). The

relaxation of this state requires deprotonation of the histidinyl cation and

only a small 0.13-Å separation and a 16° rotation of the Tyr-His

pair. The bulk of the stabilization comes from the loss of the positive charge

on the histidine residue. The small shift and modest rotation in

hydrogen-bonding geometry represents only a small (1 kcal/mol) gain in

stabilization relative to hydrogen-bonding geometry of the strained oxidized

state. Hence, the hydrogen-bonding energies and geometries of the initial

(reduced, Fig. 4A2)

and final (oxidized, Fig.

4C) states are more closely matched than in the pure

electron transfer case. This finding indicates that, in the proton-coupled

electron transfer oxidation pathway, only proton motion is likely to be

necessary.

that is

hydrogen-bonded by a histidinyl cation

(Fig. 4B2). The

relaxation of this state requires deprotonation of the histidinyl cation and

only a small 0.13-Å separation and a 16° rotation of the Tyr-His

pair. The bulk of the stabilization comes from the loss of the positive charge

on the histidine residue. The small shift and modest rotation in

hydrogen-bonding geometry represents only a small (1 kcal/mol) gain in

stabilization relative to hydrogen-bonding geometry of the strained oxidized

state. Hence, the hydrogen-bonding energies and geometries of the initial

(reduced, Fig. 4A2)

and final (oxidized, Fig.

4C) states are more closely matched than in the pure

electron transfer case. This finding indicates that, in the proton-coupled

electron transfer oxidation pathway, only proton motion is likely to be

necessary.

The proton-coupled electron transfer model presupposes that the deprotonation of the histidinyl cation is blocked at liquid helium temperature but can occur at 77 K. Presumably, this deprotonation would occur by proton transfer to another proton acceptor. The identity of this species is unknown. Clearly, the temperature dependence of this proton transfer event reflects a thermally activated process that could in itself involve protein motion. Given the lack of information on this secondary aspect of this model, more detailed discussion of this process seems premature.

The gx-value of the low-temperature-generated

intermediate did not

allow us to distinguish between the two models because the electrostatic

influence of a strong hydrogen bond from a neutral donor was estimated to be

equivalent to that of a modest hydrogen bond from a cationic donor. However,

we tend to favor the proton-coupled electron transfer model for the following

reasons: (i) the deprotonation of the reduced tyrosine requires quite

a large pKa shift from the expected pH 10 to the measured pH 7.7;

(ii) the relaxation step in the proton-coupled electron transfer

model involves mainly proton transfer (at least at the level of the Tyr-His

pair), whereas the relaxation step in the pure electron transfer model

requires more significant protein motion; and (iii) the step-wise

nature of the relaxation, involving no motion of the tyrosyl ring, argues for

a process dominated by proton movement rather than protein movement. Because

none of these arguments is particularly strong, we still entertain the pure

electron transfer model as a serious option.

intermediate did not

allow us to distinguish between the two models because the electrostatic

influence of a strong hydrogen bond from a neutral donor was estimated to be

equivalent to that of a modest hydrogen bond from a cationic donor. However,

we tend to favor the proton-coupled electron transfer model for the following

reasons: (i) the deprotonation of the reduced tyrosine requires quite

a large pKa shift from the expected pH 10 to the measured pH 7.7;

(ii) the relaxation step in the proton-coupled electron transfer

model involves mainly proton transfer (at least at the level of the Tyr-His

pair), whereas the relaxation step in the pure electron transfer model

requires more significant protein motion; and (iii) the step-wise

nature of the relaxation, involving no motion of the tyrosyl ring, argues for

a process dominated by proton movement rather than protein movement. Because

none of these arguments is particularly strong, we still entertain the pure

electron transfer model as a serious option.

The strained low-temperature state represents an unexpected intermediate

that is likely to be transiently formed at physiological temperature. Because

the intermediate is in an unusually electropositive environment, it is

predicted to be a highly oxidizing species. We have observed (unpublished

results) that this intermediate state is unstable at low temperature,

undergoing a charge recombination reaction at 40 K with the electron from the

semiquinone  (the reduced

electron acceptor) presumably via the chlorophyll cation P+ (the

oxidant of TyrD). At physiological temperature, there may be a

competition between this back reaction from the unstable intermediate and the

relaxation reaction. The previously unexplained observation that a fraction of

flash-induced

(the reduced

electron acceptor) presumably via the chlorophyll cation P+ (the

oxidant of TyrD). At physiological temperature, there may be a

competition between this back reaction from the unstable intermediate and the

relaxation reaction. The previously unexplained observation that a fraction of

flash-induced  decays

on the first few flashes (figure 1C in ref.

11) may represent this

competition reaction. The relaxation process represents a local stabilization

step that prevents this wasteful back reaction. Such local stabilization

reactions could play crucial roles elsewhere in biology, not only in tyrosine

redox chemistry, with the most obviously relevant case being TyrZ,

the sister tyrosine on the other half of the reaction center, but also in

other major processes in bioenergetics, particularly where related quinone

chemistry is also linked to proton movements

(28,

29).

decays

on the first few flashes (figure 1C in ref.

11) may represent this

competition reaction. The relaxation process represents a local stabilization

step that prevents this wasteful back reaction. Such local stabilization

reactions could play crucial roles elsewhere in biology, not only in tyrosine

redox chemistry, with the most obviously relevant case being TyrZ,

the sister tyrosine on the other half of the reaction center, but also in

other major processes in bioenergetics, particularly where related quinone

chemistry is also linked to proton movements

(28,

29).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Boussac and A. Ivancich for discussion and G. Voyard for help with maintaining the HFEPR spectrometer. This work was supported by the Human Frontier Science Organization, the European Union through the Training and Mobility of Researchers network, a Marie Curie Fellowship (to C.G.), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (to P.F.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: HFEPR, high-frequency high magnetic-field EPR; PSII, photosystem II.

References

- 1.Stubbe, J. A. & van der Donk, W. A. (1998) Chem. Rev. 98, 705–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diner, B. A. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1503, 147–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debus, R. J. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1503, 164–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koulougliotis, D., Tang, X. S., Diner, B. A. & Brudvig, G. W. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 2850–2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermass, W. F. J., Rutherford, A. W. & Hansson, O. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 8477–8481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debus, R. J., Barry, B. A., Babcock, G. T. & McIntosh, L. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 427–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutherford, A. W. & Faller, P. (2003) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 358, 245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Styring, S. & Rutherford, A. W. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 2401–2405. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diner, B. A. & Rappaport, F. (2002) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 551–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoganson, C. W. & Babcock, G. T. (1997) Science 277, 1953–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faller, P., Debus, R. J., Brettel, K., Sugiura, M., Rutherford, A. W. & Boussac, A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14368–14373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faller, P., Rutherford, A. W. & Debus, R. J. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 12914–12920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Un, S., Atta, M., Fontecave, M. & Rutherford, A. W. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 10713–10719. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Un, S., Tang, X.-S. & Diner, B. A. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mezzetti, A., Maniero, A. L., Brustolon, M., Giacometti, G. & Brunel, L. C. (1999) J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 9636–9643. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasanella, E. L. & Gordy, W. (1969) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 62, 299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berthold, D. A., Babcock, G. T. & Yocum, C. F. (1981) FEBS Lett. 134, 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Gill, P. M. W., Johnson, B. G., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Keith, T., Petersson, G. A., Montgomery, J. A., et al. (1995) gaussian 94 (Gaussian, Pittsburgh), Revision D.2.

- 19.Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. (1988) Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becke, A. D. (1988) Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becke, A. D. (1993) J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Malley, P. J. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 11732–11737. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Un, S., Dorlet, P. & Rutherford, A. W. (2001) Appl. Magn. Reson. 21, 341–361. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warncke, K., Babcock, G. T., McCracken, J. (1994) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 7332–7340. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorlet, P., Rutherford, A. W. & Un, S. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 7826–7834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanley, J., Deligiannakis, Y., Pascal, A., Faller, P. & Rutherford, A. W. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 8189–8195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faller, P., Rutherford, A. W. & Un, S. (2000) J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 10960–10963. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinfeld, D., Okamura, M. Y. & Feher, G. (1984) Biochemistry 23, 5780–5786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darrouzet, E., Moser, C. C., Dutton, P. L. & Daldal, F. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]