Abstract

In the denitrifying member of the β-Proteobacteria Thauera aromatica, the anaerobic metabolism of aromatic acids such as benzoate or 2-aminobenzoate is initiated by the formation of the coenzyme A (CoA) thioester, benzoyl-CoA and 2-aminobenzoyl-CoA, respectively. Both aromatic substrates were transformed to the acyl-CoA intermediate by a single CoA ligase (AMP forming) that preferentially acted on benzoate. This benzoate-CoA ligase was purified and characterized as a 57-kDa monomeric protein. Based on Vmax/Km, the specificity constant for 2-aminobenzoate was 15 times lower than that for benzoate; this may be the reason for the slower growth on 2-aminobenzoate. The benzoate-CoA ligase gene was cloned and sequenced and was found not to be part of the gene cluster encoding the general benzoyl-CoA pathway of anaerobic aromatic metabolism. Rather, it was located in a cluster of genes coding for a novel aerobic benzoate oxidation pathway. In line with this finding, the same CoA ligase was induced during aerobic growth with benzoate. A deletion mutant not only was unable to grow anaerobically on benzoate or 2-aminobenzoate, but also aerobic growth on benzoate was affected. This suggests that benzoate induces a single benzoate-CoA ligase. The product of benzoate activation, benzoyl-CoA, then acts as inducer of separate anaerobic or aerobic pathways of benzoyl-CoA, depending on whether oxygen is lacking or present.

The anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds has been studied in some detail in the denitrifying bacteria Thauera aromatica and Azoarcus evansii, in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris, and to a lesser extent in the iron-reducing, sulfate-reducing, and fermenting bacteria (for recent reviews, see references 19, 21, and 33). The anaerobic metabolism of aromatic acids generally starts with the transformation of the substrate to acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) derivatives which serve as substrates for further enzymes. The CoA ligases act more or less specifically on their aromatic substrate and form AMP plus PPi:

|

In T. aromatica, the anaerobic metabolism of benzoate via benzoyl-CoA and the subsequent ring reduction has been studied both on a biochemical and molecular biological level (1, 8, 14). Whereas most of the enzymes and genes required for the metabolism of benzoyl-CoA were characterized, the CoA ligase and its corresponding gene remained to be defined. It was the first aim of this work to investigate the enzyme catalyzing the initial step of anaerobic benzoate metabolism.

Besides benzoate, the bacterium can also use 2-aminobenzoate (anthranilate) as substrate for anaerobic growth, although growth was much slower (26). Extracts of 2-aminobenzoate-grown cells contained a CoA ligase acting on 2-aminobenzoate; in addition, benzoate was transformed. It was unknown whether 2-aminobenzoate was transformed by a specific 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase, as reported for other aromatic substrates in this bacterium, e.g., phenylacetate (27), 4-hydroxybenzoate (6), and 3-hydroxybenzoate (24). It was therefore the second aim of this work to address the question of whether a specific 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase was present in cells grown on 2-aminobenzoate or whether benzoate-CoA ligase acted on both benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate.

In the course of this work, it was observed that aerobic growth on benzoate also induced benzoate-CoA ligase activity. A novel pathway of aerobic benzoate oxidation via benzoyl-CoA formation was recently found in the related member of the β-Proteobacteria A. evansii (18, 28, 37; for the original proposed pathway, see reference 2). Therefore, the third aim of this work was to clarify the relationship of this aerobically induced benzoate-CoA ligase to the one induced during anaerobic growth on benzoate and nitrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Chemicals and medium components were obtained from Bio-Rad (Munich, Germany), Fluka (Neu-Ulm, Germany), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany), Serva (Heidelberg, Germany), or Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). Biochemicals were obtained from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany), Sigma-Aldrich, or Gerbu (Gaiberg, Germany). Gases were purchased from Sauerstoffwerke Friedrichshafen (Friedrichshafen, Germany). All fast-performance liquid chromatography materials and equipment were obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Freiburg, Germany) or from Sigma-Aldrich. Cyclohexa-1,5-diene-1-carboxylate was synthesized as described previously (25). Enzymes used were obtained from MBI Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and Amersham Biosciences. Nitrocellulose was obtained from Amersham Biosciences.

Bacteria, cultivation, and preparation of cell extracts.

T. aromatica DSM 6984 (3, 36) was grown anaerobically at 28°C in a mineral salt medium. For growth with benzoate, selenite and tungstate solution was omitted. Benzoate or 2-aminobenzoate and nitrate served as sole sources of energy and cell carbon. The basal medium, which was routinely used also for studies of aerobic growth, contained ammonia (15 mM) as nitrogen source. In the case of growth with 2-aminobenzoate the concentration of ammonia employed was reduced to 3 mM. Organic substrate and nitrate were continuously added in a molar ratio of 1:3.5 (benzoate-nitrate), or 1:3.6 (2-aminobenzoate-nitrate) from a concentrated stock solution, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 M aromatic substrate and 1.75 or 1.8 M potassium nitrate, respectively. For growth with other substrates see Heider et al. (20). Details of cultivation were described earlier (8, 9, 10). For comparative growth experiments wild-type and benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant cells were grown anaerobically on 5 mM aminobenzoate or benzoate plus 15 mM nitrate in flasks containing 100 ml of mineral salt medium. Aerobic growth with benzoate was tested by plating cells on Gelrite minimal medium containing 5 mM benzoate.

E. coli strains XL1-Blue MRF′ [Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] and XLOLR [Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F′ proABlacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] Su− λr] (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) used in screening and in construction of the mutagenesis vector were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (32). The following antibiotics were added to E. coli cultures at the indicated final concentrations: kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; tetracycline, 20 μg/ml; gentamicin, 15 μg/ml. Aerobic growth of A. evansii (12) on benzoate was as described previously (28).

Assays of CoA ligase activity.

Two spectrophotometric assays were used.

(i) Indirect assay.

CoA ligase activity, as well as the stoichiometry of AMP formation, substrate specificity, and Km value for benzoate, 2-aminobenzoate, ATP, and CoA were determined at 37°C using an indirect continuous spectrophotometric assay, as described previously (39). In short, the formation of AMP was coupled enzymatically to myokinase, pyruvate kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase reactions, and the oxidation of 2 mol of NADH per mol of aromatic substrate was monitored spectrophotometrically at λ = 365 nm (ɛNADH = 3.4 × 103 M−1 cm−1). The assay mixture contained 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 0.48 mM NADH, 2 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, and 0.4 mM CoA (39).

|

Aromatic acids (0.5 mM), cyclohexanecarboxylate (1 mM), cyclohexa-1,5-diene-1-carboxylate (1 mM), and cyclohexa-1-ene-1-carboxylate (1 mM), respectively, were used to start the ligase reaction. For determination of Km, benzoate (0.05 to 1 mM), CoA (0.0 5 to 0.6 mM) and ATP (0.05 to 4 mM) were used in the indicated concentration range and the respective cosubstrates were kept at near saturating concentration. For 2-aminobenzoate (2AB), a corrected absorption coefficient had to be used due to the absorption of 2-aminobenzoyl-CoA at 365 nm [ɛ = 2 × ɛNADH, 365 − ɛ2ABCoA, 365 = (2 × 3.4 × 103 − 5.5 × 103) M−1 cm−1 = 1.3 × 103 M−1 cm−1].

(ii) Direct assay.

2-aminobenzoyl-CoA exhibits a characteristic absorption maximum at a λ of 355 nm, in contrast to 2-aminobenzoate (39). The formation of 2-aminobenzoyl-CoA could therefore be directly followed spectrophotometrically at λ = 365 nm (ɛ = 5.5 × 103 M−1 cm−1). The test involved an ATP regenerating system, as described previously (39), and contained MgCl2 (5 mM), ATP (1 mM), and CoA (0.4 mM) (20). The reaction was initiated by adding 0.5 mM 2-aminobenzoate.

Purification of benzoate-CoA ligase.

The whole procedure was carried out at 4°C. A typical purification protocol is given in Table 1 (see below). Cells (10.5 g wet mass) were suspended in 11 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.8 containing 2 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM dithioerythritol (referred to as buffer A). Preparation of cell extracts was performed as described earlier (20). The enzyme fractions could be stored at −20°C following the addition of 10% (vol/vol) glycerol.

TABLE 1.

Protocol for purification of benzoate-CoA ligase from T. aromaticaa

| Purification step | Volume (ml) | Protein (mg) | Activity (μmol min−1) | Sp act [μmol min−1 (mg of protein)−1] | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract (supernatant from centrifugation at 100,000 × g) | 12.7 | 608 | ||||

| Ammonium sulfate precipitation (55%) | 9.3 | 453 | 64.8 | 0.14 | 100 | 1 |

| Dialysis | 13 | 424 | 59.4 | 0.14 | 91 | 1 |

| DEAE-Sepharose | 34.5 | 68.3 | 30.0 | 0.44 | 46 | 3.1 |

| Source 30Q | 14.5 | 29.1 | 25.3 | 0.87 | 39 | 6.2 |

| Reactive green | 39.4 | 1.2 | 19.9 | 16.5 | 31 | 118 |

Benzoate was used as substrate for the assay. Purification started from 10.5 g (wet mass) of cells grown with 2-aminobenzoate and nitrate. Similar results were obtained when cells grown with benzoate and nitrate were used or when the enzyme was purified from cells grown aerobically on benzoate.

Ammonium sulfate precipitation and dialysis.

The soluble protein fraction was precipitated with saturated ammonium sulfate solution, pH 7.8, containing 1 mM Na2EDTA to a saturation of 33%. After centrifugation (12,000 × g for 15 min), ammonium sulfate in the supernatant was increased to 55% saturation. The resulting precipitate was dissolved in 6 ml of buffer A and dialysed twice for 6 to 12 h against buffer A (exclusion size 12 to 14 kDa; Medicell International Ltd., London, England).

DEAE-Sepharose chromatography.

The dialysed protein solution was applied at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 to a DEAE-Sepharose column (Fast Flow [diameter, 32 mm; volume, 20 ml]; Amersham Biosciences) which was equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 60 ml of buffer A and afterward with 20 ml of 50 mM KCl in buffer A. The ligase was eluted with a linear gradient of 50 to 200 mM KCl in buffer A (200 ml). Fractions of 5 ml were collected, tested for ligase activity with 2-aminobenzoate and benzoate, and ligase-containing fractions were pooled.

Source 30Q chromatography.

Pooled fractions with CoA ligase activity were diluted with the same volume of buffer A and applied to an FPLC Source 30Q column (diameter, 16 mm; volume, 10 ml; Amersham Biosciences) at a flow rate of 2 ml min−1. The column was equilibrated with buffer A containing 150 mM KCl and subsequently washed with 20 ml of the same buffer. The ligase was eluted in a linear gradient of 150 to 400 mM KCl in buffer A (120 ml); the CoA ligase activity eluted at about 170 mM KCl.

Affinity chromatography.

Source 30Q benzoate-CoA ligase fraction was diluted with an equal volume of buffer A and applied at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 to a Reactive Green cross-linked agarose column (Reactive Green 19-agarose σ; diameter, 15 mm; volume, 16 ml), which was equilibrated with 50 ml of buffer A. The ligase was eluted with buffer A containing 10 mM sodium benzoate.

Determination of native molecular mass by gel filtration.

The native molecular mass of the enzyme was estimated using a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 gel filtration column (diameter, 10 mm; volume, 24 ml; Amersham Biosciences), which had been equilibrated with 100 mM KCl in buffer A; 300 μl (2 mg of protein) of concentrated protein solution was applied at a flow rate of 0.2 ml min−1. Fractions of 0.2 ml were collected and assayed for enzyme activity. The column had been calibrated with the following molecular mass marker proteins: ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), and cytochrome c (12.5 kDa).

Cloning, transformation, amplification, and purification of nucleic acids.

Standard protocols were used for DNA cloning, transformation, amplification, and purification (5, 32). Plasmid DNA was purified by the method of Birnboim and Doly (7). A λ-ZAP Express gene library of Sau3A digested genomic DNA from T. aromatica was prepared according to the ZAP Express cloning kit instruction manual (Stratagene). PCR products used as probes in screening were labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP via PCR. Probes were detected via antidigoxigenin-labeled aprotinin, nitroblue tetrazolium chloride, and X-Phosphate (5-chloro-4-bromo-3-indolyl-phosphate toluidine salt) (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany). The DNA clones and vectors used are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

DNA clones and vectors used in this study

| Name | Characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pGEX 6P-1 | AmprlacIq | Amersham Biosciences |

| pJQ200SK | Gmr sacB traJ | 39 |

| pUC4-KSAC vector | Kanr Ampr | Amersham Biosciences |

| pBK-CMV | Kanr | Stratagene |

| pBK-CMVLig1 | Includes bp 2811-4910 of T. aromatica DNA fragment | This work |

| pBK-CMVLig2 | Includes bp 3478-6669 of T. aromatica DNA fragment | This work |

| pBK-CMVLig3 | Includes bp 1-3889 of T. aromatica DNA fragment | This work |

Cloning of the DNA containing the gene for anaerobically induced benzoate-CoA ligase.

The primers used are summarized in Table 3. A degenerate oligonucleotide LigFor was derived from a 9-amino-acid (-aa) sequence (NTPPAIKIP) of the determined N-terminal amino acid sequence of the benzoate-CoA ligase, taking into account the codon usage of the bacterium. Two more primers LigRev1 and LigRev2 were designed based on two amino acid consensus sequences of known AMP-binding sites of various CoA ligases of T. aromatica and A. evansii (CFWLYSSG and GSTGAPK, respectively). All three primers were used in PCR (95°C for 2.5 min, 45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min [30 cycles]) to amplify a 0.5-kbp digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe P1. The probe was used for screening the λ-ZAP Express gene library; the DNA probe and phagemid DNA were hybridized at 68°C for 16 h. A 2.1-kb clone pBK-CMV-Lig1 was found containing part of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene. Two new primers F and R were derived from the 3′ end and 5′ end of this clone to amplify a 1.2-kb probe for further screening. Recombinant plasmids were maintained in E. coli XL1-Blue.

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| mutligfor | CGGGATCCTCCCATCGCCATG | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| multigrev | TGCGCAGCTGCACCTTTGTTCATTCTGCCG | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| kkpstfor | AACTGCAGTTAGAAAACTCATCGAGCATC | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| kkpstrev | TTCTGCAGAAAGCCACGTTGTGTCTCAAAATC | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| BcoAfor | GCCCATAGGCGAAGAACAGC | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| BcoArev | GGCGAACTGTTCGCCTATGGGC | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| sligfor | GGGGCGCTTCGAGGAAACCA | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| sligrev | ACACCAGCTCGGCTACCC | Benzoate-CoA ligase mutant |

| Ligfor | AACACCCCSCCSGCSATCAAGATCCC | Screening probe |

| LigRev1 | GGSGWSGWGTASAGCCAGAAGCA | Screening probe |

| LigRev2 | CCTTSGGSGCGCCGGTSG WGCC | Screening probe |

| R | GGGTGCAACCTGCTTGCAGGGC GTGG | Screening probe |

| F | CCCGCTCACCTTGAGCATGTCGTCG | Screening probe |

Restriction sites for the first two primers are underlined.

DNA sequencing and computer analysis.

Purification of plasmid DNA used in sequencing reactions was carried out as described in E.Z.N.A. plasmid miniprep kit I manual (PeqLab, Erlangen, Germany). DNA sequences were determined either with ALFexpress automated sequencer (Amersham Biosciences) or carried out by J. Alt-Mörbe (Labor für DNA-Analytik, Freiburg, Germany). DNA and amino acid sequences were analyzed with the BLAST network service at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, Md.).

Construction of a benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant.

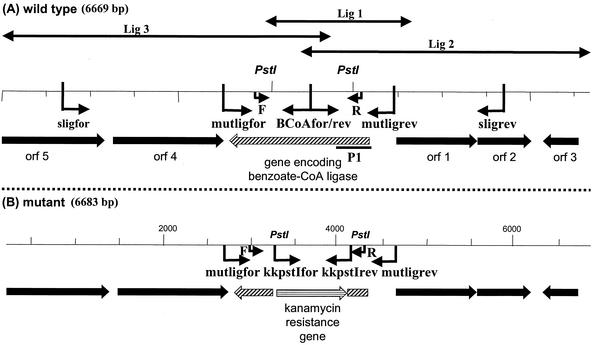

Standard protocols were used for DNA cloning, transformation, amplification, and purification (5, 32). The benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant was constructed via a partial gene deletion and replacement of the deleted part by a kanamycin resistance Geneblock (Amersham Biosciences). Primers were used which bind upstream and downstream of the gene coding for the benzoate-CoA ligase; they carried restriction sites for BamHI and SalI, respectively (mutligfor and mutligrev). The benzoate-CoA ligase gene and parts of the adjacent intergenic regions were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pGex vector, using E. coli XL1-Blue as a host. The recombinant vector was cut by PstI resulting in an in-frame deletion of a 918-bp fragment of the ligase gene. The kanamycin resistance cassette was amplified with primers kkpstIfor and kkpstIrev using the pUC4-KSAC vector (Amersham Biosciences) as template. The amplified resistance gene was cut by PstI and ligated into the benzoate-CoA ligase gene. The T. aromatica DNA fragment carrying the kanamycin cassette was cut out with BamHI and SalI and cloned into the sacB-containing suicide vector pJQ200MK (31). The resulting plasmid was transformed into E. coli S17-1 (35) and transferred by conjugation into T. aromatica (30). The mating mixture was plated on Gelrite minimal medium containing sucrose (5 mM), 3-hydroxybenzoate (2.5 mM), phenylacetate (2.5 mM), glutarate (4 mM), succinate (4 mM), acetate (4 mM), and kanamycin (50 μg ml−1). Exconjugants, which had lost the sacB-containing vector by double recombination, were selected by screening for sucrose resistance. Presence of the desired benzoate-CoA ligase mutation was confirmed by colony PCR, using the primer pairs sligfor-kkpstIrev, sligrev-kkpstIfor, mutligfor-kkpstIrev, mutligrev-kkpstIfor, mutligfor-BcoArev, and mutlirev-BcoAfor (illustrated in Fig. 1). Primer binding sites for mutligfor and mutligrev should be present in wild-type and mutant cells. Primer binding sites for BcoAfor and BcoArev should not be available in mutant clones because their binding sites are on the deleted part of the ligase gene. Binding sites for kkpstIfor and kkpstIrev are part of the DNA of mutant cells.

FIG. 1.

Organization of the ORFs identified nearby the gene coding for benzoate-CoA ligase (A) and comparison between wild type and benzoate-CoA gene mutant (B). (A) Sequenced T. aromatica wild-type DNA fragment. ORF 1, putative fusion protein of a transcription regulator protein and putative shikimate kinase I. ORF 2, hypothetical protein. ORF 3, MarR-like transcription regulator protein. ORF 4, boxA, similar to boxA of A. evansii. ORF 5, boxB, similar to boxB of A. evansii. Double arrows indicate the clones obtained in screening (pBK-CMV-Lig1, -Lig2, and -Lig3). The position of the screening probe P1 is indicated by thick line. Binding sites of the primers used for benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant characterization are indicated by arrows. (B) Organization of the gene locus in the benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant. Primer binding sites are indicated by arrows.

Further methods employed.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12.5% polyacrylamide) was performed as described by Laemmli (23). Proteins were visualized using Coomassie blue staining (38) or silver staining (29). Protein was routinely determined by the Bradford method (11) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. N-terminal amino acid sequences were obtained by gas- and liquid-phase sequencing with an Applied Biosystems 473A sequencer, as described earlier (22). Antibodies raised against BoxA protein from A. evansii and Western blot experiments as well as the enzymatic assay of BoxA were performed as described previously (28).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data for benzoate-CoA ligase gene, ORF 1, boxA, and boxB (bp 1 to 5800) reported here were submitted to the GenBank database (accession number AF373594).

RESULTS

CoA ligase(s) in T. aromatica acting on benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate during anaerobic growth.

Extracts of cells grown anaerobically with benzoate or 2-aminobenzoate and nitrate were analyzed for CoA ligase activities, which would form CoA thioesters from benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate, respectively. A coupled spectrophotometric assay was used which followed the oxidation of NADH. In case of 2-aminobenzoate, the formation of 2-aminobenzoyl-CoA could also be followed in a direct spectrophotometric assay due to the characteristic absorption maximum of 2-aminobenzoyl-CoA at 355 nm. These two methods gave identical results. The accuracy of activity measurements using cell extract (supernatant from centrifugation at 100,000 × g) was impaired by the high endogenous NADH oxidation rate and by the presence of unknown inhibitory substances in the extract. As a result, all activities were determined near substrate saturation following ammonium sulfate precipitation (55% saturation) of cell extracts. The specific activities obtained (Table 4) do not refer to the protein content of the ammonium sulfate precipitated enzyme fraction; rather the values are corrected and refer to the original protein content of cell extracts.

TABLE 4.

Specific CoA ligase activities of T. aromatica acting on benzoate and 2-aminobenzoatea

| Growth substrate | Activity [nmol min−1 (mg of protein)−1)] of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Benzoate-CoA ligase | 2-Aminobenzoate-CoA ligase | |

| 2-Aminobenzoate | 45 | 36 |

| Benzoate | 115 | 50 |

| Phenol | 109 | 64 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoate | 78 | 38 |

| 3-Hydroxybenzoate | 60 | 32 |

| Toluene | 126 | 86 |

| Phenylacetate | 114 | 74 |

| Acetate | 58 | 28 |

| Glutarate | 36 | 22 |

| Benzoate + oxygen | 89 | 36 |

Cells grown under denitrifying conditions with different aromatic substrates were tested. The cell extracts were precipitated with ammonium sulfate (55% saturation) prior to measurement of the enzyme activities in the dissolved precipitate. The specific activity refers to mg of protein in cell extract (supernatant from centrifugation at 100,000 × g). The values given are the average of at least two parallel measurements with less than 10% deviation.

Cells grown on 2-aminobenzoate exhibited a benzoate-CoA ligase activity which was 1.5 to 2.5 times higher than 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase activity. The ratio of 2-aminobenzoate- to benzoate-CoA ligase activity (0.4 to 0.8) was similar in cells grown anaerobically on benzoate, 2-aminobenzoate, phenol, 4-hydroxybenzoate, 3-hydroxybenzoate, toluene, and phenylacetate. This suggested that during growth on 2-aminobenzoate no specific 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase was induced. The specific 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase activity of 36 nmol min−1 (mg of protein)−1 in 2-aminobenzoate-grown cells may be sufficient to explain the slow growth of the bacterium with 2-aminobenzoate and nitrate (16-h generation time with 2-aminobenzoate, compared to 6-h generation time with benzoate).

Search for benzoate- and 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase activities.

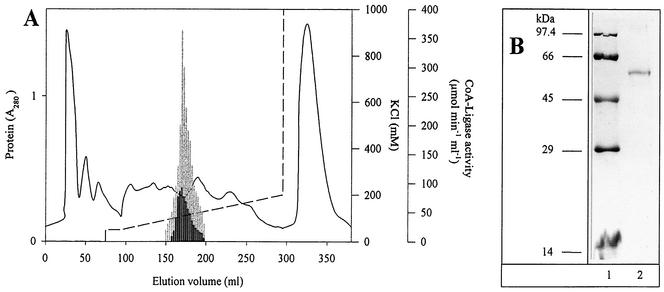

The following experiment was designed to determine whether a single CoA ligase is acting on both substrates benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate, or whether two CoA ligases—one acting on benzoate, the other one acting on 2-aminobenzoate—were responsible for benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate activation. Extract of cells grown under denitrifying conditions with 2-aminobenzoate was separated by DEAE-Sepharose chromatography. All fractions were analyzed for CoA ligase activities acting on benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate (Fig. 2A). Only one enzyme fraction containing CoA ligase activity was found, and both CoA ligase activities were observed in that fraction. The ratio of 2-aminobenzoate- to benzoate-CoA ligase activity was approximately 0.6 and constant in all subfractions, suggesting that only one enzyme was present which acted on both substrates.

FIG. 2.

Search for 2-aminobenzoate- and benzoate-CoA ligase activities in T. aromatica and purification of benzoate-CoA ligase. (A) Elution profile of 2-aminobenzoate- and benzoate-CoA ligase activities after DEAE-Sepharose chromatography of extracts of cells grown on 2-aminobenzoate plus nitrate. Thick column, 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase activity; grey column, benzoate-CoA ligase activity. Solid line, protein (A280); dashed line, KCl. Both enzyme activities were measured in a coupled spectrophotometric assay. (B) SDS-PAGE (Coomassie stain) of purified benzoate-CoA ligase from T. aromatica. Lane 1, molecular mass marker proteins; lane 2, enzyme. Approximately 10 and 6 μg of protein was loaded on lane 1 and 2, respectively.

Purification of benzoate-CoA ligase from anaerobically grown cells.

This conclusion was confirmed by further purification of the CoA ligase from 2-aminobenzoate-grown cells. Only one enzyme was found, which acted on both substrates (Table 1; Fig. 2B). A homogeneous protein with a subunit of about 58 kDa was obtained with a yield of 31% following 118-fold purification. The native molecular mass of the enzyme determined by gel filtration was 58 kDa. This suggested a monomeric composition. The N-terminal amino acid sequence was determined as follows: MYTLS VADHS NTPPA IKIPE RYNAA DDLIG rNLlA (lowercase characters indicate uncertain amino acids). The UV-visible spectrum of the colorless enzyme showed an absorption maximum near 280 nm and no further absorbance at higher wavelengths.

Similarly, benzoate-CoA ligase was also purified from cells grown anaerobically with benzoate and nitrate and studied. The enzyme was indistinguishable from that obtained from 2-aminobenzoate-grown cells with regard to the specific activity, the yield, the native molecular mass and the molecular mass of the protein in SDS-PAGE. Also, 11 N-terminal amino acids were analyzed (MYTLS VADHS N) and found to be identical with the sequence of the enzyme prepared from cells grown on 2-aminobenzoate. These facts indicate that the two enzyme preparations from two different batches of anaerobically grown cells yielded identical enzymes.

Catalytic properties of benzoate-CoA ligase.

The catalytic properties of the enzyme were studied; the results are shown in Table 5. Per mole of aromatic substrate added, 1 mol of AMP was formed from ATP. The apparent Km values for benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate were 25 ± 7 and 150 ± 50 μM, respectively. The apparent Vmax value for benzoate was 16.5 μmol min−1 mg−1, and the turnover number with benzoate was 16 s−1. The Vmax value for 2-aminobenzoate was approximately 60% of the value observed with benzoate. Due to its catalytic properties this enzyme is termed benzoate-CoA ligase. The enzyme also acted on the mono-fluoro analogues of benzoate (0.5 mM each aromatic substrate) and with some alicyclic compounds derived from benzoate (1.0 mM). The apparent Km value for ATP was 370 ± 70 μM, and for CoA a value of 160 ± 30 μM was found. These properties are compared with those of other benzoate-CoA ligases from different sources. The optimum pH was near pH 8.5.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of properties of benzoate-CoA ligase of T. aromatica with similar aromatic acid-CoA ligases acting on benzoate or 2-aminobenzoatea

| Enzyme | Growth | Refer- ence(s) | Organism or culture | Molecular mass (kDa)

|

Apparent Km values (μM)

|

Substrate preference (% of benzoate)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native | SDS- PAGE | Benzoate | 2-Amino- benzoate | CoA- SH | ATP | Benzoate | 2-Amino- benzoate | 2-Fluoro- benzoate | 3-Fluoro- benzoate | 4-Fluoro- benzoate | Cyclohexane carboxylate | Cyclohexa- 1,5-diene-1- carboxylate | Cyclohexa- 1-ene-1- carboxylate | ||||

| Benzoate-CoA ligase | Anaerobic | This work | T. aromatica | 58 | 58 | 16 | 150 | 180 | 440 | 100 | 60 | 122 | 89 | 100 | <1 | 23 | 8 |

| Benzoate-CoA ligase | Anaerobic | 1 | A. evansii | 120 | 54 | 9 | 300 | 89 | 125 | 100 | 38 | 67 | 33 | 54 | 7 | NDb | ND |

| Benzoate-CoA ligase | Aerobic | 2 | A. evansii | 130 | 56 | 11 | 180 | 105 | 277 | 100 | 37 | 155 | 86 | 138 | 1 | ND | ND |

| 2-Aminobenzoate- CoA ligase | Anaerobic | 1 | A. evansii | 60 | 60 | 35 | 13 | 20 | 83 | 100 | 100 | 110 | 56 | 100 | 3 | ND | ND |

| 2-Aminobenzoate- CoA ligase | Aerobic | 1 | A. evansii | 65 | 65 | 75 | 15 | 26 | 40 | 91 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 90 | 5 | ND | ND |

| Benzoate-CoA ligase | Anaerobic | 14a, 17 | R. palustris | 60 | 60 | 0.6-2 | ND | 90-120 | 2-3 | 100 | <1 | 102 | ND | 10 | 1 | ND | 13 |

| Benzoate-CoA ligase | Anaerobic | 4 | Syntrophic | 420 | 58 | 30 | ND | 60 | 560 | 100 | 4 | 93 | 56 | 75 | ND | ND | 6 |

| Benzoate-CoA ligase | Aerobic | 5a | Clarkia breweri | 59 | 64.5 | 45 | ND | 130 | 95 | 100 | 50 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Activities of the enzymes described here were determined by the indirect couples spectrophotometric assay with nearly saturating concentrations of the respective cosubstrates ATP (1 mM), CoA (0.4 mM), Mg2+ (0.5 mM), aromatic organic acid (0.5 mM), and alicyclic organic acid (1 mM). None of the following substrates was accepted by any of the described benzoate-CoA ligases (rate, <1%): monochlorobenzoate isomers, monohydroxybenzoate isomers, phenylacetate, 3-aminobenzoate, and 4-aminobenzoate. The only exception is 2-hydroxybenzoate, which was transformed at 5% by the enzyme from R. palustris. Note that Clarkia breweri is a green plant.

ND, not determined.

Cloning and sequencing of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene.

Degenerate oligonucleotides were derived on the basis of the determined N-terminal amino acid sequence of the benzoate-CoA ligase (forward primer) and the common amino acid consensus sequence of known AMP-binding sites of various CoA ligases (reverse primer). The primers were used in PCR to amplify an ∼500-bp digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe (P1) (Fig. 1A). The probe was used for screening of a λ-ZAP Express gene library.

A 2.1-kb clone was found (pBK-CMV-Lig1) (Table 2; Fig. 1A) containing part of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene and upstream sequence. Two new primers (F and R) (Table 3) were derived from the obtained sequence and used to amplify a new 1.2-kb probe for further screening. Two additional clones, which overlapped by 410 bp, were obtained (pBK-CMV-Lig2 and -Lig3; Fig. 1A; Table 2) and sequenced. The sequence was analyzed via BLAST network service.

Clone pBK-CMV-Lig2 (3.2 kb) contained about 0.7 kb of the 5′-end sequence of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene and about 2.5 kb of upstream sequence. Three putative ORFs (ORFs 1 to 3) were found in the upstream sequence of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene, with transcription directions as indicated in Fig. 1.

Clone pBK-CMV-Lig3 (3.9 kb) contained about 1.2 kb of the 3′ sequence of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene and 2.7 kb of the downstream sequence. Two putative ORFs (ORFs 4 and 5), which were transcribed in the opposite direction as the benzoate-CoA ligase gene, were identified in the downstream region of benzoate-CoA ligase (Fig. 1A).

The gene encoding the benzoate-CoA ligase was sequenced double-stranded, as well as ORF 1, which codes for a putative regulator/shikimate kinase fusion protein. ORFs 2 to 5 were sequenced only single-stranded. The deduced 35 N-terminal amino acid residues of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene were identical to those of the purified protein. The calculated molecular mass of the benzoate-CoA ligase of 57 kDa was close to the apparent molecular mass of 58 kDa of the enzyme determined by SDS-PAGE and gel filtration.

The gene encoding the benzoate-CoA ligase showed high similarity to several CoA ligases. The highest similarity was recorded with another gene bank entry of a putative benzoate-CoA ligase of T. aromatica (Table 6). The deduced N-terminal amino acid sequence (mptls aadht asppe iripr) of this enzyme differs from the one reported here. Unfortunately, no functional or biochemical characterization of that gene product is available yet.

TABLE 6.

Properties of genes and gene products of the sequenced T. aromatica DNA fragmenta

| Gene | G+C content of the gene (mol %) | Length of intergenic region to next ORF | Putative function of gene product | Molecular mass (kDa) | Isoelectric point | Similar protein(s) in databases | % Identity | % Similarity | E value | ACR no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orf 3 | 68.7 | 104 | Regulator | 16 | 11.4 | Probable transcription regulator protein (Ralstonia solanacearum) | 53 | 68 | 4e-29 | NP_521785 |

| Putative marR family transcriptional regulator (Streptomyces coelicolor A3) | 28 | 54 | 1e-5 | NP_631735 | ||||||

| orf 2 | 65 | 40 | Unknown | 23 | 5.7 | Hypothetical protein (Azoarcus evansii) | 47 | 55 | 8e-37 | AAN39379 |

| Hypothetical protein (Rhodopseudomonas palustris) | 29 | 46 | 3e-14 | ZP_00011237 | ||||||

| orf 1 | 66.2 | 288 | Regulator | 34 | 5.9 | Regulator (Azoarcus evansii) | 72 | 82 | 1e-107 | AAN39374 |

| Hypothetical protein (Burkholderia fungorum) | 48 | 63 | 8e-66 | ZP_00030198 | ||||||

| Benzaote-CoA ligase gene | 66.6 | 92 | Benzoate-CoA ligase | 57 | 5.3 | Benzoate-CoA ligase (Thauera aromatica) | 78 | 86 | 0 | CAD21683 |

| Benzoate-CoA ligase (Azoarcus evansii) | 74 | 83 | 0 | AAN39371 | ||||||

| orf 4 | 62.5 | 110 | Benzoyl-CoA oxygenase component A | 46 | 5.5 | Benzoyl-CoA oxygenase component A (Azoarcus evansii) | 80 | 89 | 0 | AAN39377 |

| Hypothetical protein (Burkholderia fungorum) | 63 | 72 | 1e-148 | ZP_00027560 | ||||||

| orf 5 | 65.6 | Benzoyl-CoA oxygenase component B | ND | ND | Benzoyl-CoA oxygenase component B (Azoarcus evansii) | 87 | 91 | 0 | AAN39376 | |

| Hypothetical protein (Burkholderia fungorum) | 65 | 80 | 1e-135 | ZP_00027561 |

Similarity searches were done with the the program blastp (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Percent identity is defined as percentage of amino acids that are identical between two proteins. Percent similarity is defined as percentage of amino acids that are identical or conserved between two proteins. The expect value (E value) estimates the statistical significance of the match, specifying the number of matches with a given score that is expected in a search of a database of this size absolutely by chance.

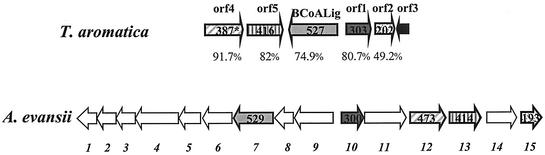

Features of five genes adjacent to the benzoate-CoA ligase gene.

ORFs 1, 2, 4, and 5 showed high similarity (up to 87% identity) to four genes probably involved in a novel pathway of aerobic benzoate metabolism in A. evansii (Fig. 3, Table 6) and to similar gene clusters of other proteobacteria (18). This benzoate pathway proceeds via benzoyl-CoA, as does the anaerobic pathway, though further metabolism is via different derived CoA thioesters (18, 28, 37). ORF 1 coded for a 34-kDa protein showing similarity to putative regulatory proteins in its N-terminal part and to putative shikimate kinase I proteins in the C-terminal half. A potential ATP-binding P loop (GLRGAGKT, aa 142 to 149) and a shikimate kinase I domain (RRIEQRTLERVIRDHDRAVISAGGGVV, aa 191 to 219) were identified. ORF 2 encoded a hypothetical protein with a calculated molecular mass of 23 kDa. Highest similarity was found with a hypothetical protein of A. evansii. ORF 4 codes for a putative protein of 46 kDa. This protein is considered to be the electron donating component (Box A) of a benzoyl-CoA dioxygenase/reductase acting on benzoyl-CoA (28, 37). ORF 5 showed high similarity to the gene boxB, which codes for the benzoyl-CoA dioxygenase component BoxB. These two genes of A. evansii were discussed elsewhere (18, 28). ORF 3 showed similarity to MarR-like regulator proteins.

FIG. 3.

Correlation of genes for benzoate-CoA ligase and adjacent genes in T. aromatica with genes coding for enzymes and regulatory proteins involved in a novel aerobic benzoate oxidation pathway in A. evansii. Corresponding ORFs are indicated by same colors (white, ORFs in A. evansii without corresponding ORF in T. aromatica). Numbers in arrows indicate the deduced numbers of amino acids in the gene products. The percentages indicate the percentages of similar amino acids in the corresponding ORF products. An asterisk indicates an ORF that is incompletely sequenced. Putative functions of A. evansii ORFs: ORF 7, benzoate-CoA ligase; ORF 10, regulatory protein; ORF 12, BoxB; ORF 13, BoxA; ORF 15, hypothetical protein. For further information, see reference 18.

Characterization of a benzoate-CoA ligase induced during aerobic growth on benzoate.

T. aromatica is also able to grow under aerobic conditions with benzoate as the sole carbon and energy source. Growth was slow in liquid media; growth in solid media was best with Gelrite as solidifying agent. Surprisingly, cells grown aerobically with benzoate also contained benzoate-CoA ligase activity (50 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1) assayed by the coupled spectrophotometric assay using benzoate as substrate. The enzyme was purified 200-fold to homogeneity and studied (data not shown). The yield was 22% and the specific activity obtained was 10 μmol min−1 mg of protein−1. On SDS-PAGE a single protein band corresponding to a molecular mass of 58 kDa was seen. The 15 N-terminal amino acids were MYTLS VADHS NTPPA. This sequence is identical to the one determined for the anaerobically induced enzyme. Also, substrate specificities and apparent KM values were indistinguishable from those of the previously purified enzyme. This indicates that the same CoA ligase was induced during aerobic growth with benzoate as was found in cells grown anaerobically with benzoate or 2-aminobenzoate.

Further indication for the operation of the novel aerobic benzoyl-CoA oxidation pathway in T. aromatica.

In A. evansii the initial two steps in aerobic benzoate oxidation are as follows (18, 28; A. Zaar, J. Gescher, W. Eisenreich, A. Bacher, and G. Fuchs, unpublished results): Benzoate is converted to benzoyl-CoA by benzoate-CoA ligase. Benzoyl-CoA is then transformed in an NADPH- and oxygen-dependent reaction to [ring-2,3]dihydroxydihydrobenzoyl-CoA by a benzoyl-CoA dioxygenase/reductase. This enzyme consists of two proteins. BoxA is the reductase component which oxidizes NADPH, BoxB is the actual dioxygenase. In the absence of BoxB, BoxA catalyzes the benzoyl-CoA-dependent oxidation of NADPH with O2 forming H2O2. As noted above, both genes for homologues of BoxA and BoxB were present in the gene cluster near the benzoate-CoA ligase gene.

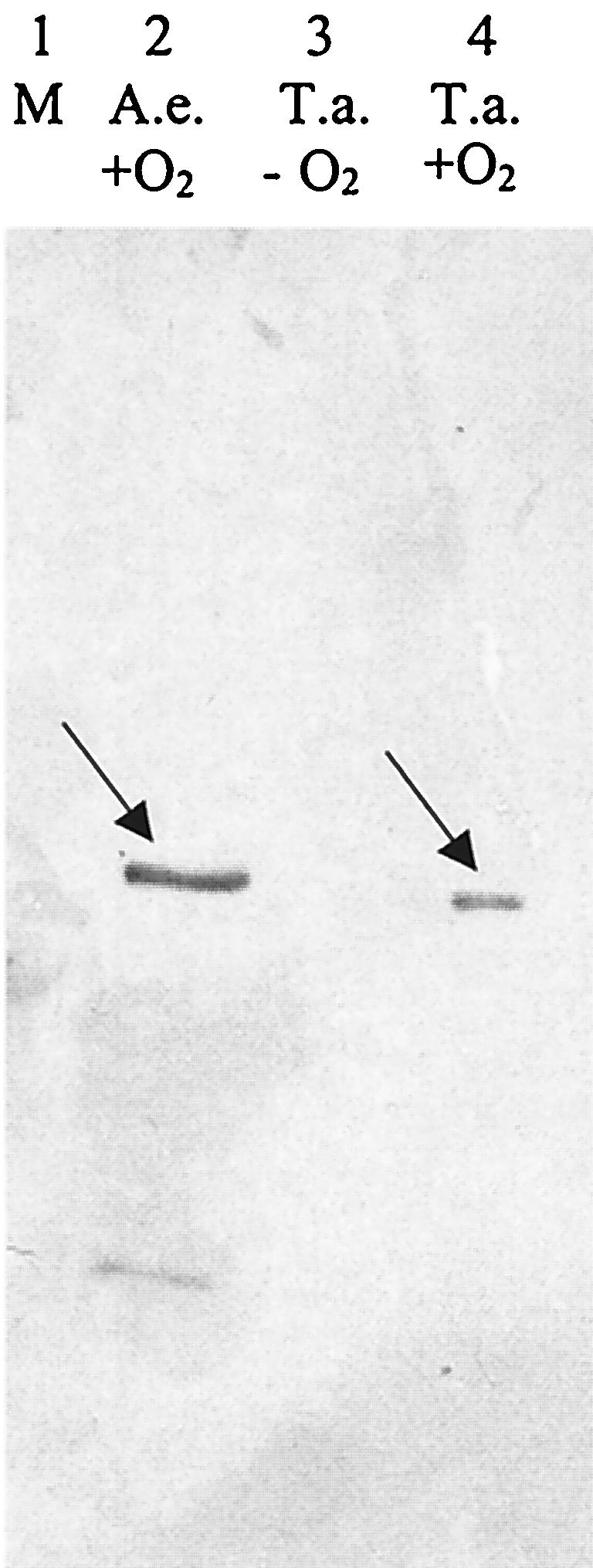

The presence of BoxA in extracts of T. aromatica cells grown aerobically on benzoate was documented by two experiments. First, polyclonal antibodies raised against purified BoxA from A. evansii were used to test cell extract from T. aromatica for the presence of BoxA-like proteins. The antibodies cross-reacted with a single protein band in extracts of cells grown aerobically on benzoate; this protein had a molecular mass similar to that of BoxA. Cells grown anaerobically on benzoate did not contain this protein (Fig. 4). Second, extracts were tested for BoxA activity, i.e., by following benzoyl-CoA-dependent oxidation of NADPH with O2. Such activity was detected in extract of cells grown aerobically on benzoate (8 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1) but not in cells grown anaerobically on benzoate.

FIG. 4.

Immunodetection of benzoyl-CoA dioxygenase/reductase component A (BoxA, reductase component) using polyclonal antibodies raised against purified BoxA from A. evansii. Lane 1, molecular mass standard lane. Lane 2, extract of A. evansii cells grown aerobically on benzoate as control. Lane 3, extract of T. aromatica cells grown anaerobically on benzoate and nitrate. Lane 4, extract of T. aromatica cells grown aerobically on benzoate.

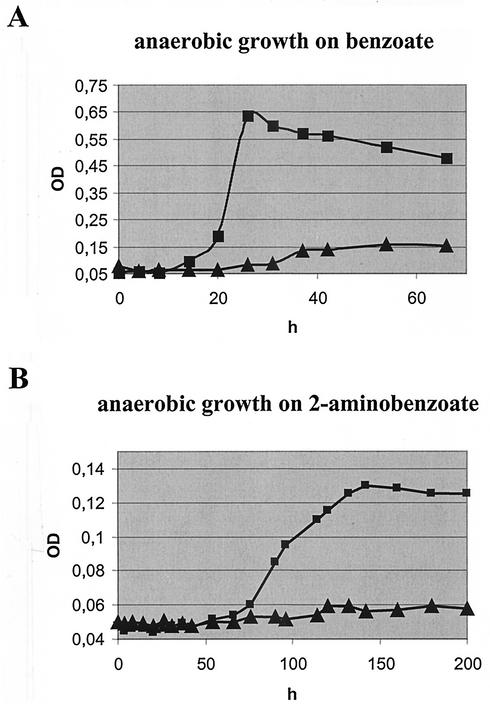

Construction and phenotype of benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant.

A benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant was constructed by homologous recombination between the wild-type chromosome and an insertionally inactivated version of the gene carried on the plasmid pJQ200MK. Colony PCR confirmed that the resulting strain carried a kanamycin resistance cassette inserted at the expected location and that the kanamycin resistance is a result of a double-crossover between wild-type DNA and the cloned fragment. No wild-type gene could be amplified via PCR using the primer pairs mutligfor-BcoArev and mutligrev-BcoAfor (Fig. 1). The benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant failed to grow aerobically on Gelrite plates containing 5 mM benzoate, whereas growth on other, nonaromatic substrates was unimpaired. Furthermore, it failed to grow with wild-type growth rates anaerobically on benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate as sole carbon source (Fig. 5). This shows that the benzoate-CoA ligase is essential for growth on these substrates not only under anaerobic conditions but also for aerobic growth on benzoate.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of anaerobic growth on benzoate (A) and 2-aminobenzoate (B) between wild-type (▪) and benzoate-CoA ligase gene mutant (▴) T. aromatica. Growth was measured as optical density at 578 nm in cuvettes with a 1-cm light path.

DISCUSSION

Function of benzoate-CoA ligase.

In T. aromatica one single benzoate-CoA ligase appears to function in anaerobic benzoate metabolism, in anaerobic 2-aminobenzoate metabolism, as well as in aerobic benzoate metabolism. Benzoate-CoA ligase was the only enzyme found in cells grown anaerobically on 2-aminobenzoate that acted on 2-aminobenzoate; no specific 2-aminobenzoate-CoA ligase could be identified, as it was reported for other aromatic acids such as 3-hydroxybenzoate, 4-hydroxybenzoate, and phenylacetate (6, 24, 27).

Cells growing anaerobically on benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate with generation times of 6 h and 16 h, respectively, transform their aromatic substrate with specific rates of 66 and 25 nmol min−1 mg−1. The apparent Km values for benzoate (16 μM) and 2-aminobenzoate (150 μM) as well as the relative Vmax values (100% versus 60%) of the enzyme for the two substrates and the specific activities in cell extracts (Table 4) are sufficient to explain the relative growth rates on benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate, respectively.

Interestingly, most CoA ligases acting on benzoate are also active with 2-aminobenzoate, in contrast to 3- or 4-aminobenzoate or hydroxybenzoate isomers (Table 5). Obviously, as benzoate-CoA ligase is induced in 2-aminobenzoate-grown cells, in T. aromatica 2-aminobenzoate acts not only as substrate for the enzyme but also as inducer for the expression of the benzoate-CoA ligase gene.

Benzoate-CoA ligase does not act on the monohydroxybenzoate analogues or on phenylacetate. Obviously, the bacterium possesses other CoA ligases acting on these substrates. Indeed, 3-hydroxybenzoate-, 4-hydroxybenzoate-, and phenylacetate-CoA ligases have been characterized in this and other bacteria which specifically metabolize such aromatic acids (6, 24, 27). 2-Hydroxybenzoate-CoA ligase has been inferred from measurements with cell extracts (10) and from the inability of benzoate-CoA ligase to act on 2-hydroxybenzoate, but the enzyme has not been studied yet.

CoA ligase family.

Benzoate-CoA ligase belongs to the growing family of CoA ligases forming AMP and pyrophosphate. The deduced amino acid sequences show several conserved domains; the highly conserved nucleotide-binding domain was even successfully used in this work to derive a primer for PCR amplification of a fragment of the corresponding gene. The catalytic properties (Table 5) of benzoate-CoA ligases from different organisms are quite similar. The general properties of this class of enzymes have been discussed elsewhere (5a, 14a, 20).

Anaerobic 2-aminobenzoate metabolism.

2-Aminobenzoyl-CoA seems to be reduced to a nonaromatic alicyclic CoA thioester product. The only enzyme present in cells of T. aromatica grown anaerobically on 2-aminobenzoate that would transform 2-aminobenzoyl-CoA was purified and shown to be benzoyl-CoA reductase (U. Feil and G. Fuchs, unpublished results; see also reference 26a). It is unknown whether additional enzymes are involved specifically in 2-aminobenzoate metabolism. In 3-hydroxybenzoate metabolism, benzoyl-CoA reductase also is responsible for aromatic ring reduction. However, a substrate-specific CoA ligase as well as additional enzymes are required for 3-hydroxybenzoate metabolism (24). It will be interesting to comparatively study the metabolism of 2-hydroxybenzoate.

Regulation on the whole-cell level and regulator proteins.

Genes involved in anaerobic benzoate metabolism have been cloned and sequenced from the α-Proteobacteria member R. palustris (16) and from the β-Proteobacteria members A. evansii (18) and T. aromatica (14) (for a review, see reference 19). In the first two bacteria, the gene for benzoate-CoA ligase as well as genes for putative regulatory proteins are part of one gene cluster, together with the genes coding for enzymes of the general anaerobic benzoyl-CoA pathway, whereas in T. aromatica they seem to be separate. Two ORFs 1 and 3 near the gene for benzoate-CoA ligase code for putative regulator proteins in T. aromatica. Their functions are completely unknown. Genes similar to ORF 3, a member of the MarR family, have been found in gene clusters responsible for anaerobic 4-hydroxybenzoate metabolism in T. aromatica (13) and for aerobic 2-aminobenzoate metabolism in A. evansii (34). In R. palustris, two proteins, AadR and BadR, regulate expression of benzoyl-CoA reductase and probably other components of the general benzoyl-CoA pathway in response to oxygen and benzoate, respectively (15). The badR gene, present in the benzoate gene cluster, codes for a regulator protein of the MarR family which is activated by benzoate or benzoyl-CoA. The aadR gene maps to a region of the R. palustris chromosome outside the benzoate degradation gene cluster. AadR is a member of the Fnr family of regulators.

Surprisingly, the gene for anaerobic benzoate-CoA ligase was located next to ORFs which are possibly involved in aerobic benzoate degradation. Similar ORFs are found in a gene cluster of the related A. evansii probably coding for a novel aerobic benzoate degradation pathway (2, 18, 28, 37). Therefore, it appears that in T. aromatica only one CoA ligase isoenzyme is responsible for anaerobic growth with benzoate and 2-aminobenzoate and for aerobic growth with benzoate. However, we do not have any explanation for the possible role of another putative benzoate-CoA ligase gene present in this bacterium which has been sequenced by G. Burchardt and coworkers, University of Greifswald, Germany, and which has been deposited in the database (see Table 6 for accession number). In R. palustris, benzoate-CoA ligase, encoded by badA, is one of three ligases able to catalyze benzoyl-CoA formation during anaerobic growth on benzoate (14a).

Nature of the inducer.

It has been proposed previously that the actual inducer of the anaerobic benzoate degradation genes in T. aromatica should be benzoate rather than benzoyl-CoA (20). This conclusion is corroborated by the finding that the gene for benzoate-CoA ligase is found most likely in its own operon separate from the genes coding for the anaerobic degradation pathway. This indicates that the gene for CoA ligase and the other genes of the anaerobic or aerobic benzoate pathways cannot be cotranscribed. The most probable explanation is that benzoate-CoA ligase is induced by benzoate. Benzoyl-CoA then may act as inducer for the following genes required for either the aerobic or anaerobic metabolism of benzoyl-CoA. The choice depends on the availability of oxygen. 2-Aminobenzoate probably acts as additional inducer. Furthermore, benzoate-CoA ligase is always induced in cells growing anaerobically on aromatic substrates, even when the aromatic substrate is converted to benzoyl-CoA rather than to benzoate (20, 21). Examples are phenol, 4-hydroxybenzoate, phenylacetate, and toluene (Table 4). This seems to suggest that also benzoyl-CoA may act as inducer. Another possibility is that benzoyl-CoA is always hydrolyzed to some degree to benzoate by thioesterases which are present in cell extracts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. Thanks are due to Juliane Alt-Mörbe, Labor für DNA-Analytik, Freiburg, Germany, for help in DNA sequencing and to Diana Laempe, Freiburg, Germany, for a gift of cyclohexa-1,5-diene-1-carboxylate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altenschmidt, U., B. Oswald, and G. Fuchs. 1991. Purification and characterization of benzoate-coenzyme A ligase and 2-aminobenzoate-coenzyme A ligases from a denitrifying Pseudomonas sp. J. Bacteriol. 173:5494-5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altenschmidt, U., B. Oswald, E. Steiner, H. Herrmann, and G. Fuchs. 1993. New aerobic benzoate oxidation pathway via benzoyl-coenzyme A and 3-hydroxybenzoyl-coenzyme A in a denitrifying Pseudomonas sp. J. Bacteriol. 175:4851-4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders, H.-J., A. Kaetzke, P. Kämpfer, W. Ludwig, and G. Fuchs. 1995. Taxonomic position of aromatic-degrading denitrifying Pseudomonas strains K 172 and KB 740 and their description as new members of the genera Thauera, as Thauera aromatica sp. nov., and Azoarcus, as Azoarcus evansii sp. nov., respectively, members of the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:327-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auburger, G., and J. Winter. 1992. Purification and characterization of benzoyl-CoA ligase from syntrophic, benzoate-degrading, anaerobic mixed culture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37:789-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 5a.Beuerle, T., and E. Pichersky. 2002. Purification and characterization of benzoate:coenzyme A ligase from Clarkia breweri. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 400:258-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biegert, T., U. Altenschmidt, C. Eckerskorn, and G. Fuchs. 1993. Enzymes of anaerobic metabolism of phenolic compounds. 4-Hydroxybenzoate-CoA ligase from a denitrifying Pseudomonas species. Eur. J. Biochem. 213:555-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnboim, H., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boll, M., and G. Fuchs. 1995. Benzoyl-coenzyme A reductase (dearomatizing), a key enzyme of anaerobic aromatic metabolism. ATP dependence of the reaction, purification and some properties of the enzyme from Thauera aromatica strain K172. Eur. J. Biochem. 234:921-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonting, C. F. C., S. Schneider, G. Schmidtberg, and G. Fuchs. 1995. Anaerobic degradation of m-cresol via methyl oxidation to 3-hydroxybenzoate by a denitrifying bacterium. Arch. Microbiol. 164:63-69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonting, C. F. C., and G. Fuchs. 1996. Anaerobic metabolism of 2-hydroxybenzoic acid (salicylic acid) by a denitrifying bacterium. Arch. Microbiol. 165:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilising the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun, K., and D. T. Gibson. 1984. Anaerobic degradation of 2-aminobenzoate (anthranilic acid) by denitrifying bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:102-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breese, K., and G. Fuchs. 1998. 4-Hydroxybenzoyl-CoA reductase (dehydroxylating) from the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica. Prosthetic groups, electron donor, and genes of a member of the molybdenum-flavin-iron-sulfur proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 251:916-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breese, K., M. Boll, J. Alt-Mörbe, H. Schägger, and G. Fuchs. 1998. Genes coding for the benzoyl-CoA pathway of anaerobic aromatic metabolism in the bacterium Thauera aromatica. Eur. J. Biochem. 256:148-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Egland, P. G., J. Gibson, and C. S. Harwood. 1995. Benzoate-coenzyme A ligase, encoded by badA, is one of three ligases able to catalyze benzoyl-coenzyme A formation during anaerobic growth of Rhodopseudomonas palustris on benzoate. J. Bacteriol. 177:6545-6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egland, P. G., and C. S. Harwood. 1999. BadR, a new MarR family member, regulates anaerobic benzoate degradation by Rhodopseudomonas palustris in concert with AadR, an Fnr family member. J. Bacteriol. 181:2102-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egland, P. G., D. A. Pelletier, M. Dispensa, J. Gibson, and C. S. Harwood. 1997. A cluster of bacterial genes for anaerobic benzene ring degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6484-6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geissler, J. F., C. S. Harwood, and J. Gibson. 1988. Purification and properties of benzoate-coenzyme A ligase, a Rhodopseudomonas palustris enzyme involved in the anaerobic degradation of benzoate. J. Bacteriol. 170:1709-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gescher, J., A. Zaar, M. Mohamed, H. Schägger, and G. Fuchs. 2002. Genes coding for a new pathway of aerobic benzoate metabolism in Azoarcus evansii. J. Bacteriol. 184:6301-6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwood, C. S., G. Burchhardt, H. Herrmann, and G. Fuchs. 1999. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds via the benzoyl-CoA pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:439-458. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heider, J., M. Boll, K. Breese, S. Breinig, C. Ebenau-Jehle, U. Feil, N. Gad'on, D. Laempe, B. Leuthner, M. Mohamed, S. Schneider, G. Burchhardt, and G. Fuchs. 1998. Differential induction of enzymes involved in anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica. Arch. Microbiol. 170:120-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heider, J., and G. Fuchs. 1997. Microbial anaerobic aromatic metabolism. Anaerobe 3:1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch, W., H. Schägger, and G. Fuchs. 1998. Phenylgloxylate:NAD+ oxidoreductase (CoA benzoylating), a new enzyme of anaerobic phenylalanine metabolism. Eur. J. Biochem. 251:907-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laempe, D., M. Jahn, K. Breese, H. Schägger, and G. Fuchs. 2001. Anaerobic metabolism of 3-hydroxybenzoate by the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica. J. Bacteriol. 183:968-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laempe, D., W. Eisenreich, A. Bacher, and G. Fuchs. 1998. Cyclohexa-1, 5-dien-1-carboxyl-CoA hydratase, an enzyme involved in anaerobic metabolism of benzoyl-CoA in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica. Eur. J. Biochem. 255:618-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lochmeyer, C., J. Koch, and G. Fuchs. 1992. Anaerobic degradation of 2-aminobenzoic acid (anthranilic acid) via benzoyl-CoA and cyclohex-1-enecarboxyl-CoA in a denitrifying bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 174:3621-3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Möbitz, H., and M. Boll. 2002. A Birch-like mechanism in enzymatic benzoyl-CoA reduction: a kinetic study of substrate analogues combined with an ab initio model. Biochemistry 41:1752-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohamed, M. E.-S., and G. Fuchs. 1993. Purification and characterization of phenylacetate-coenzyme A ligase from a denitrifying Pseudomonas sp., an enzyme involved in the anaerobic degradation of phenylacetate. Arch. Microbiol. 159:554-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammed, M. E.-S., A. Zaar, C. Ebenau-Jehle, and G. Fuchs. 2001. Reinvestigation of a new type of aerobic benzoate metabolism in the proteobacterium Azoarcus evansii. J. Bacteriol. 183:1899-1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrissey, J. G. 1981. Silver stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels: a modified procedure with enhanced uniform sensitivity. Anal. Biochem. 117:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parales, R. E., and C. S. Harwood. 1993. Construction and use of a new broad-host-range lacZ transcriptional fusion vector, pHRP309, for gram− bacteria. Gene 133:23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quandt, J., and M. F. Hynes. 1993. Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 127:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Schink, B., B. Phillip, and J. Müller. 2000. Anaerobic degradation of phenolic compounds. Naturwissenschaften 87:12-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schühle, K., M. Jahn, S. Ghisla, and G. Fuchs. 2001. Two similar gene cluster coding for enzymes of a new type of aerobic 2-aminobenzoate (anthranilate) metabolism in the bacterium Azoarcus evansii. J. Bacteriol. 183:5268-5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: Transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tschech, A., and G. Fuchs. 1987. Anaerobic degradation of phenol by pure cultures of newly isolated denitrifying pseudomonads. Arch. Microbiol. 148:213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaar, A., W. Eisenreich, A. Bacher, and G. Fuchs. 2001. A novel pathway of aerobic benzoate catabolism in the bacteria Azoarcus evansii and Bacillus stearothermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24997-25004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zehr, B. D., T. J. Savin, and R. E. Hall. 1989. A one-step, low background Coomassie staining procedure for polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 182:157-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziegler, K., K. Braun, A. Böckler, and G. Fuchs. 1987. Studies on the anaerobic degradation of benzoic acid and 2-aminobenzoic acid by a denitrifying Pseudomonas strain. Arch. Microbiol. 149:62-69. [Google Scholar]