Abstract

We reported previously the isolation of a novel cell death-suppressing gene from maize (Zea mays) encoded by the Lls1 (Lethal leaf spot-1) gene. Although the exact metabolic function of LLS1 remains elusive, here we provide insight into mechanisms that underlie the initiation and propagation of cell death associated with lls1 lesions. Our data indicate that lls1 lesions are triggered in response to a cell-damaging event caused by any biotic or abiotic agent or intrinsic metabolic imbalance—as long as the leaf tissue is developmentally competent to develop lls1 lesions. Continued expansion of these lesions, however, depends on the availability of light, with fluence rate being more important than spectral quality. Double-mutant analysis of lls1 with two maize mutants oil-yellow and iojap, both compromised photosynthetically and unable to accumulate normal levels of chlorophyll, indicated that it was the light harvested by the plant that energized lls1 lesion development. Chloroplasts appear to be the key mediators of lls1 cell death; their swelling and distortion occurs before any other changes normally associated with dying cells. In agreement with these results are indications that LLS1 is a chloroplast-localized protein whose transcript was detected only in green tissues. The propagative nature of light-dependent lls1 lesions predicts that cell death associated with these lesions is caused by a mobile agent such as reactive oxidative species. LLS1 may act to prevent reactive oxidative species formation or serve to remove a cell death mediator so as to maintain chloroplast integrity and cell survival.

lls1 (lethal leaf spot-1) is a maize (Zea mays) mutation, characterized by the formation of necrotic spots that expand continuously to kill the entire leaf and eventually the whole plant. The developmentally programmed phenotype of lls1 manifests in a cell autonomous fashion as evidenced by the discrete border between mutant and revertant tissue in sectored plants (Gray et al., 1997) and is suggestive of the involvement of an endogenous program in lls1 cell death. Because this mutation is inherited in a strictly recessive fashion, it is likely that the wild-type Lls1 gene functions to positively maintain cell homeostasis (Ullstrup and Troyer, 1967; Johal et al., 1994). The Lls1 gene has been cloned. Although it appears to encode a novel protein specific to plants, it does have two motifs, a Rieske-type Fe-sulfur center and a mononuclear non-heme Fe-binding site, that are found in the aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases of bacteria. Because of the fact that the biochemical function of these enzymes is to degrade aromatic hydrocarbons, we hypothesized previously that LLS1 may also work by breaking down a phenolic mediator of cell death in plants (Gray et al., 1997). This proposal remains contentious, however, because the nature of the substrate, if any, for LLS1 remains unknown and we have now found these motifs in a small family of plant enzymes, two of which are known to function in chlorophyll b and Gly betaine biosynthesis (below).

The lls1 mutation belongs to a class of defects in plants called disease lesions mimics in which lesions resembling infection sites are formed in the absence of a pathogen (Greenberg, 1997; Morel and Dangl, 1997; Gray and Johal, 1998; Buckner et al., 2000). Several of these genes have now been cloned in anticipation of identifying molecular components that play a direct role in controlling cell death and the hypersensitive response (HR) in plants (Morris et al., 1998; Kliebenstein et al., 1999; Yin et al., 2000). These studies reveal that lesion mimic genes encode a variety of functions including membrane receptors (Mlo and Rp1), a putative transcription factor regulating superoxide dismutase (Lsd1), and salicylate and sphingolipid signaling (Acd6 and Acd11; Hu et al., 1996; Buschges et al., 1997; Collins et al., 1999; Devoto et al., 1999; Kliebenstein et al., 1999; Rate et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2001; Broderson et al., 2002). The genes underlying other lesion mimic phenotypes appear to play a more direct role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Blockage of metabolic processes such as the synthesis or degradation of chlorophyll (by Les22-encoding uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and acd2-encoding red chlorophyll catabolite reductase, respectively), results in the accumulation of porphyrin intermediates that become toxic free radicals when cells are exposed to excess light (Hu et al., 1998; Molina et al., 1999; Ishikawa et al., 2001; Mach et al., 2001). A deficiency in fatty acid biosynthesis (by the mod1 gene encoding an enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase) causes pleiotropic effects on plant growth and results in premature cell death (Mou et al., 2000).

Although there is a ubiquitous association of these mutants with tissue death, careful examination is required to determine which ones may represent defects in genes and mechanisms that control programmed cell death (PCD; Greenberg, 1997; Morel and Dangl, 1997; Gray and Johal, 1998; Buckner et al., 2000, Mou et al., 2000). Our knowledge of how plants might accomplish PCD remains rudimentary. In animal studies, the cellular features of PCD events such as cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and phagocytosis by neighboring cells are widely recognizable (Haecker, 2000). The nDNA of dying cells is degraded into oligonucleosomal ladders. A class of Cys proteases termed caspases enables such dismantling of the cell. Produced as zymogens, caspases are kept in check directly or indirectly by suppressors of cell death. Some of these suppressors of cell death do so by maintaining the integrity of mitochondria (Hengartner, 2000). When animal cells are accidentally injured they exhibit a swelling of the cell and organelles known as oncosis evidenced later by chromatin clumping and phagocytosis (Majno and Joris, 1995). The extent to which similar molecular components participate in the apoptotic and oncotic cell death pathways is not yet fully known.

Although studies of lesion mimics have identified genes and mechanisms that are largely unique to plants, only in a few cases have the details of how cells affected in each of these mutants undergo cell death. Do they follow the paradigm of apoptotic cell death, which is shown to be conserved biologically across the entire animal kingdom, or do they follow a sequence of events that is unique to plants? The present investigation was undertaken to explore the nature of cell death mechanisms that underlie the initiation and propagation of lls1 lesions. The results obtained clearly support a central role for light absorbed by chloroplasts in lls1 cell death. Although the results do not indicate that lls1 cells undergo a PCD event, they do prompt the idea that the regulation of chloroplast integrity should be considered as a possible means by which some cell death events may be controlled in plants.

RESULTS

lls1 Lesions Exhibit Some Features of Cell Death Induced by Infectious Agents

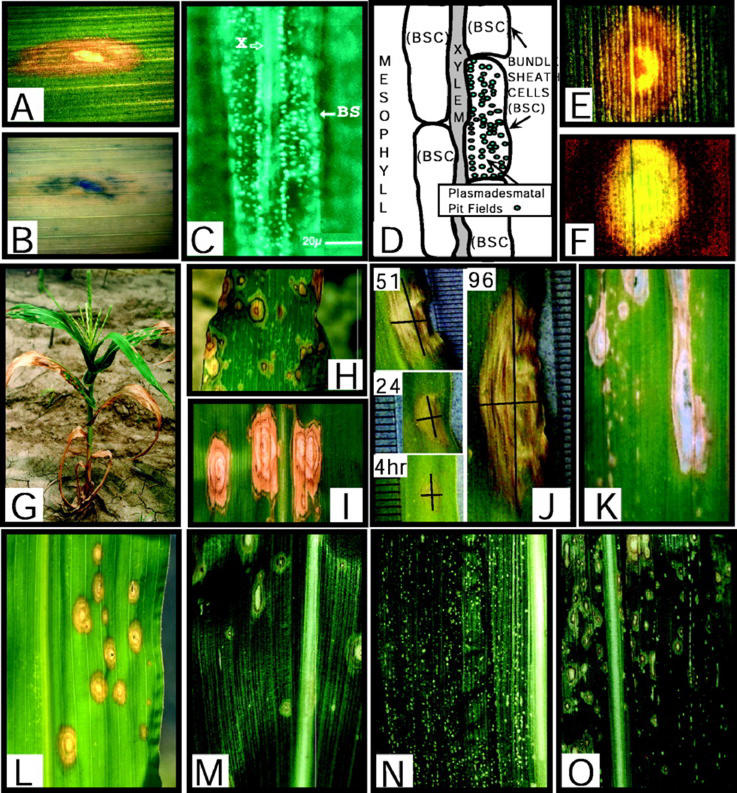

Plants often respond to pathogens by unleashing a cell death program at or around the site of infection (Hammond-Kosack and Jones, 1996). This cell death reaction, often associated with HR, results in cellular collapse and the formation of necrotic lesions. Necrotic regions where irreversible membrane damage or cell death has occurred are apparent when lls1 lesions are stained with trypan blue (Fig. 1, A and B; Dietrich et al., 1994). Two cytological markers that are almost always found associated with the HR are the deposition of callose and the accumulation of autofluorescent lesions in and around infection sites (Aist et al., 1988; Koga et al., 1988). To assess whether lls1 lesions exhibit features characteristic of HR lesions, we monitored the induction of these responses during the development of lls1 lesions. Callose deposition was observed in most cells within lls1 lesions. The BS cells were the first to form callose, deposited as plugs in the plasmodesmatal pit fields (Fig. 1, C and D). This callose response was observed several vascular bundles distant from the actual lesion site, indicating that a stress signal emanating from the dying cells triggered the response. Autofluorescence, which is thought to reflect accumulation of stress-related phenolic compounds, was also observed in lls1 lesions (Fig. 1, E and F). It appeared to be restricted to dying tissue. These results show that lls1 lesions exhibit some features of cell death that are associated with the HR. We also attempted to discern if DNA fragmentation, which is a marker of some plant PCD events, occurs in lls1 dying cells. We did not detect an oligonucleosomal ladder in lls1 lesioned leaves but this may have been because of the asynchronicity of rapidly dying cells in these lesions (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Histological features and inducible expression of lls1 lesion phenotype during development. A, White light trans-illumination of an lls1 lesion (5×). B, Trypan blue staining in area of necrosis of same lesion, as in A. C, Callose plugging of plasmadesmatal fields in BS cells of an lls1 plant. Picture shows aniline blue-stained unsectioned leaf tissue observed under UV light. Black arrow indicates an individual BS cell outside the periphery of the observable dying cells (which is to the left of the field) that has begun to deposit callose in the plasmadesmatal fields. The white arrow indicates the location of a neighboring xylem cell in the vascular bundle. D, Cartoon indicating bundle sheath (BS) and xylem cell boundaries in A. The plasmadesmatal pit fields, containing up to 100 plasmadesmata/pit fields, are highlighted for one cell in blue. E, White light trans-illumination of an lls1 lesion (40×). F, Blue-light autofluorescence of same lesion as in E. G, Developmental expression of lls1 lesions. Field-grown lls1-ref/lls1-ref plant at the nine-leaf stage. H, Close-up view of typical spreading lesions on an expanded leaf of an lls1-ref/lls1-ref plant grown under field conditions. Occasionally, the concentric rings exhibit a dark coloration as shown here. I, Close-up view of field-grown lls1 lesions showing the concentric ring appearance of lesions and elongate shape of lesions. J, Time lapse series showing expansion of an individual lls1 lesion over a period of 96 h. The ruler markings in each picture are 1 mm apart. K, Lesions induced in an lls1/lls1 plant 7 d after infection with a nonpathogenic strain of C. carbonum. L, Lesions induced in a region of an lls1/lls1 leaf by pinprick wounding 4 d earlier. This region of the leaf was competent for lesion formation but normal spontaneous lesions had not yet progressed to this region of the leaf. M, Spontaneous lesion development on an lls1/lls1 plant from a population segregating for Les101 and lls1. Lesions exhibit a low density. N, Spontaneous lesion development on an Les101 plant from a population segregating for Les101 and lls1. Lesions exhibit a high density. O, Spontaneous lesion development on an Les101/+ lls1/lls1 plant from a population segregating for Les101 and lls1. Lesions are initiated as les101 lesions and progress to an lls1 phenotype with a density that of Les101 lesions.

Cellular Damage Is Required for lls1 Lesion Initiation

Lesion mimics have been categorized into two classes: those in which lesions stay small and discrete (initiative class), and those in which lesions, once formed, continue to expand (propagative class). The initiative class mutants may have defects that inappropriately trigger a cell death program, whereas mutants of the propagative class may have defects in negative regulators of cell death (Walbot et al., 1983; Greenberg and Ausubel, 1993; Dietrich et al., 1994; Johal et al., 1994). We described previously how the lls1 phenotype follows a developmental gradient with lesions forming first near the tip of the oldest leaf and then gradually moving downward toward its base (Johal et al., 1994; Gray et al., 1997). This pattern is repeated progressively on every leaf up the plant (Fig. 1G). However, within a region of a leaf that has attained developmental competence, lls1 lesions appear to form in a random pattern (Fig. 1H). Once initiated, lls1 lesions then continue to expand and often appear to be slowed by leaf veins leading to a longitudinal appearance (Fig. 1, I and J). This expansion was measured over time (Fig. 1J) and it is estimated that longitudinal expansion (7.7 mm d−1) occurs approximately 5.6 times faster than latitudinal expansion (1.8 mm d−1). The continuous lesion expansion implies that lls1 mutation is defective in a mechanism involved in the containment of cell death. The impedance of the spread of cell death by vascular bundles suggests dilution of a diffusible cell death-promoting factor or alternatively the reduced production of the factor by non-photosynthetic vascular cells. These observations prompted the closer examination of the immediate events that underlie lls1 lesion formation.

To address this, we treated mutant plants in a variety of ways. First, we asked how lls1 plants react to pathogens that trigger HR. This was accomplished by inoculating lls1 seedlings with an avirulent strain of Cochliobolus carbonum that induces only necrotic flecks at the site of penetration (Johal and Briggs, 1992). Initially, the tissue reacted by producing flecks, which appeared at the same rate and intensity as they did on wild-type siblings. However, as the competence to form lls1 lesions developed, most sites expanded to form lls1 lesions on mutant leaves (Fig. 1K). Inoculations with other maize pathogens, including C. heterostrophus and Puccinia sorghi, gave similar results (data not shown), which indicated that some general stress associated with pathogen invasion probably provided a trigger for lls1 lesion initiation.

To test whether this stress was caused by physical injury associated with fungal penetration, lls1 leaves were wounded by pinpricks. Like infection sites, all wound sites transformed into lls1 lesions when the tissue acquired the potential to express the mutant phenotype (Fig. 1L), suggesting that a damaged or dying cell can serve as the trigger for lls1 lesion initiation. This conclusion is supported by the additive phenotype of double mutants in which lls1 was coupled either with Les-101 or Les-22. The latter are two dominant Les mutations of the initiation class, whose production of lesions preceded those caused by lls1 (Fig. 1, M–O; Johal et al., 1994). In the case of Les101, lesions also form at a much higher density (136.3 ± 21.2 lesions/unit area2) than “spontaneous” lls1 lesions on similarly aged leaves (2.5 ± 1.4 lesions/unit area2). We inspected Les101/lls1 double mutants over successive days and monitored the progression of individual lesions in a time lapse fashion. The phenotype was initially of the respective Les type, however, as the leaf acquired developmental competence to express lls1 many Les lesions transformed into lls1-like lesions (Fig. 1O; an increased lls1 lesion density of 19.5 ± 5.9 lesions/unit area2) that rapidly expanded to overlap with other Les lesions and consume the whole leaf. Taken together, these results clearly indicate that biotic or abiotic cellular damage, irrespective of the nature of the agent that caused it, serves as a signal to initiate an lls1 lesion. Even so-called “spontaneous” lesions that form on lls1 plants in the apparent absence of any wounding (e.g. in a growth chamber) may reflect an unidentified endogenous stress such as the accumulation of a phototoxic metabolite (see below).

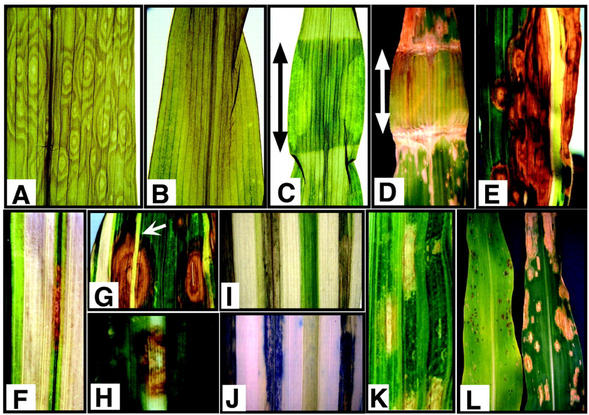

Light Harvested by Photosynthetic Tissue Is Required for lls1 Lesion Formation

The lls1 lesions typically exhibit alternating circles of light and dark necrotic tissue, suggesting that expansion of lls1 lesions is subject to influence by environmental factors (Fig. 2A). Because concentric rings largely disappear when lls1 mutants are grown under continuous illumination (Fig. 2B), light may play a role in the expression of lls1 lesions. To investigate this possibility, maize leaves were covered with aluminum foil at different stages of lesion development. Macroscopic lesions did not form on covered parts of the leaf, and the ones that had already initiated stopped growing once the leaf was covered (Fig. 2C). We have not determined absolutely that microscopic cell death is inhibited in the dark but the growth of lesions induced by mechanical wounding was similarly impeded (data not shown), indicating that light plays a deciding role at least in lls1 lesion expansion, if not also lesion induction.

Figure 2.

Requirement of light for lesion development and suppression of the lls1 phenotype in photosynthetically compromised mutants. A, Multiple initiation points for cell death during diurnal cycle. Image shows close-up view of a dead lls1/lls1 lesioned leaf that was grown with an approximately 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle. The center of each set of concentric rings represents the initiation points of cell death in this leaf region. B, “Wave” of cell death during continuous illumination. Image shows close-up view of a dying lls1/lls1 lesioned leaf that was grown under continuous illumination in a growth chamber. Cell death is seen to process as a wave from the tip of the leaf toward the base as opposed to a confluent “leaf spot” pattern. C, Requirement of light for lesion formation in an lls1/lls1 plant. The leaf shown was protected by wrapping aluminum foil around the region indicated by the arrow. Lesions developed in the region exposed to light but not in the protected region. A similar protective effect was observed for lesions induced by pinprick wounding (not shown). D, Light intensity versus wavelength experimental arrangement. Leaf regions not yet exhibiting lesions were protected by foil or a transparent plexiglass filter (red for the leaf shown here) around the region indicated by the arrow. After lesion formation on the lower side of the covered region, the filter was removed and the underlying tissue examined for lesions. Here, a red plexiglass filter 3 mm in thickness prevented lesion formation. E, Suppression of lls1 lesion formation in pale-green or albino sectors of an iojap (ij) mutant. Lesions developed in an lls1/lls1 ij/ij plant but only in dark-green tissue. Lesions formed on either side of pale green or albino sectors but never within the albino sectors. F, Suppression of lls1 lesion formation in pale-green or albino sectors of an iojap (ij) mutant. Lesions developing in a narrow green sector propagate lengthways but not into the neighboring albino sectors. G, Suppression of lls1 lesion formation in pale-green or albino sectors of an iojap (ij) mutant. In this instance, an lls1 lesion appears to “traverse” a narrow pale green sector (arrow). H, Les4 lesions will form in the albino sectors of an iojap (ij) mutant. The lesions of the dominant lesion mimic les4 formed in both pale-green and albino sectors (shown) of a Les4/+ ij/ij double mutant plant. I and J, Albino sector of an ij/lls1 leaf traversed by an lls1 lesion is still alive. The dead tissue of a leaf section viewed by white light in I is revealed by trypan blue staining in J. K, Suppression of lls1 lesion formation in pale-green sectors of an ncs7 mutant. Lesions developed in an lls1/lls1 NCS2 plant but only in dark-green tissue. L, Suppression of lls1 lesion formation in an oy1-700 mutant. Similarly positioned leaves from field-grown plants of the same age are compared from a population segregating for lls1 and oy1-700. The plant on the right (lls1/lls1 Oy1-700) exhibits typical lls1 lesion development, whereas the plant on the left (lls1/lls1 oy1-700/+) exhibited smaller lesions that did eventually coalesce but at a greatly reduced rate. The reduction of lesion formation in lls1/lls1 oy1-700/+ plants often caused the suppression of lls1/lls1 lethality (permitting seed set).

To investigate whether it was the quantity or quality of light that allowed lls1 lesion expansion, mutant leaves were covered with plastic filters that allowed transmission of different wavelengths of light. Except for the far-red filter, which transmitted less than 1% of incident sunlight (approximately 7 μmol m−2 s−1), none of the filters could prevent lesion progression under full exterior sunlight (1,600–1,700 μmol m−2 s−1). Under greenhouse conditions where overall incident light was approximately 25% of full sunlight, filters that transmitted approximately 40 μmol m−2 s−1 or less provided a protective function (Fig. 2D). These results are consistent with the conclusion that lls1 lesions are promoted by a higher fluence rate of incident light, but they do not reveal if it was specifically the light harvested for photosynthesis that was responsible for lls1 lesion growth.

We used a genetic approach to further explore this question. We generated double mutants of lls1 with ij1 (iojap-1), NCS2 (non-chromosomal stripes), and Oy1–700 (Oil yellow-1), which are all compromised in their ability to capture light or photosynthesize effectively. ij1 is a recessive nuclear mutation that produces albino (homoplastidic) and pale green (heteroplastidic) stripes on an otherwise normal green leaf (Han et al., 1992). Chloroplasts affected in ij1 do not contain ribosomes, largely lack thylakoids, and exhibit undetectable levels of ribulose-biphosphate carboxylase and ATPase activity (Thompson et al., 1983). Pale-green or albino stripes of NCS2, a maternally inherited defect, result from a deficiency of PSI (Marienfeld and Newton, 1994). In both of these variegated backgrounds, lls1 lesions formed only in normal green tissues and failed to initiate or develop in either the pale green or albino sectors (Fig. 2, E–G and I–K). Moreover, lls1 lesions that formed in green tissues quickly stopped expanding when they reached albino or pale-green sectors (Fig. 2, E, F, I, and J). An exception to this trend, however, was noted when such chlorophyll-deficient sectors were narrow. In these situations, although the lls1 lesion still failed to annihilate the albino tissue, it was able to traverse such narrow stripes and resume growth in green tissue on the other side (Fig. 2G). The lack of trypan blue staining in the traversed albino tissue indicates that the cells therein are still alive (Fig. 2, I and J). Apparently, the signal(s) mediating the propagation of lls1 cell death is somewhat diffusible, but the fact that lls1 lesions fail to develop or expand into nongreen tissue indicates that some activity related to light harvesting or photosynthesis is important in expression of lls1 lesions. That this is an lls1-specific phenomenon is indicated by the observation that Les4 lesions are not suppressed in albino areas (Fig. 2H).

The interpretation that some factor or activity associated with light harvesting by photosynthetic pigments is required for lls1 lesion development is further supported by the behavior of lls1 in the Oy1-700 background. Oy1-700 is a semidominant mutation with a defect in Mg-chelatase activity (Polacco and Walden, 1987; Neuffer et al., 1997). As a result, the mutant has reduced chlorophyll levels, only 30% to 40% compared with normal plants. In fact, chlorophyll b is largely absent in this mutant. On leaves of lls1 mutants that are heterozygous for Oy1-700, lesions initiated at a similar frequency (1.8 ± 1.5 lesions/unit area2) to those in wild-type tissue (1.5 ± 1.6 lesions/unit area2). However these lesions expanded at a greatly reduced rate than in normal lls1 mutants (Fig. 2L). Even though lesions may eventually coalesce in older leaves of lls1/Oy1-700 double mutants, plants often survive to maturity under field conditions, allowing maintenance of lls1 mutants in homozygous conditions.

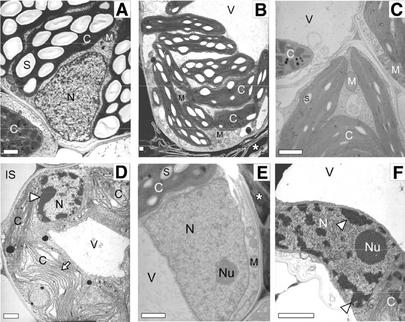

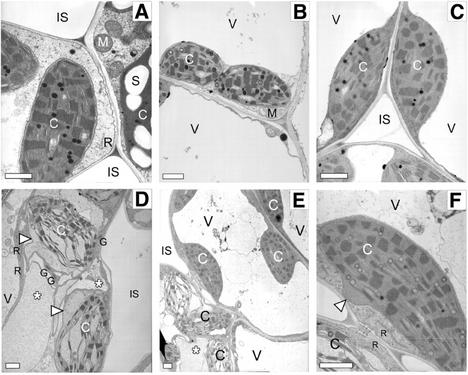

Death of lls1 Cells Is Mediated by Chloroplasts

To characterize cellular events that might be causally involved in the death of lls1 cells, cells in and around freshly induced lesions were examined by electron microscopy. To make sure that cells of similar age and developmental status were compared, lesions were induced intentionally by puncturing leaves that had just acquired developmental competence to form lls1 lesions. Mutant cells from wound sites were compared with uninjured cells from the same leaf, as well as with cells sampled from equivalent punctured and uninjured sites of wild-type leaves. Although tissue was examined at 21 and 42 h post-wounding, only images collected at 21 h are shown. This is because similar ultrastructural changes were found at both time points, even though the lesions had progressed farther from the site of wounding in the 42-h post-wounding tissue.

Both mesophyll and BS cells taken from intact sites of lls1 mutant leaves were almost indistinguishable from equivalent cells of wild-type leaves. These leaf cells exhibited the typical dimorphic anatomy characteristic of C4 metabolism, meaning that the starchless, oval chloroplasts of mesophyll cells were highly granal, whereas the starch-filled, cigar-shaped chloroplasts of BS cells were devoid of grana (Figs. 3C and 4C). One difference that existed between the mutant and wild-type cells was the number and size of starch grains in chloroplasts of BS cells, both of which were significantly abated in mutant cells (6.2 ± 3.7 granules choroplast−1) compared with the wild type (10.3 ± 3.3 granules choroplast−1; P = 0.0023, n = 11 and 26 chloroplasts, respectively).

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of BS cell chloroplasts and nuclei in injured and uninjured (21 h post-pinprick wounding) wild-type and lls1 leaves. A, BS cell in uninjured wild-type leaf tissue. B, BS cell adjoining dead cells in injured wild-type leaf tissue. Asterisk indicates location of dead cell. C, BS cell in uninjured lls1 tissue. D, BS cell adjoining dead cell in injured lls1 leaf tissue. An increased amount of heterochromatin (arrowhead) is present in the nucleus. Note also the apparent folding of the thylakoid membranes (arrow). E, Nucleus of a BS cell adjoining a dead cell in injured wild-type leaf tissue. Asterisk indicates location of dead cell. Note the small amount of heterochromatin. F, Nucleus of a BS cell adjoining a dead cell in injured lls1 leaf tissue. A large amount of heterochromatin is present in this nucleus (arrowheads). Bars = 1 μm. n, Nucleus; Nu, nucleolus; C, chloroplast; S, starch granule; M, mitochondrion; V, vacuole; R, rough endoplasmic reticulum; IS, intercellular space.

Very striking changes, however, were observed in cells when the mutant leaf was wounded to incite the lls1 lesion. The most prominent of these changes was an alteration in the structure of chloroplasts of mesophyll and BS cells alike, although the type of change differed in the two cell types. Chloroplasts in mesophyll cells adjacent to the wound-induced lls1 lesion were highly swollen, whereas their thylakoid membranes possessed a relatively normal organization (Fig. 4D). In contrast, chloroplasts of BS cells adjacent to the wound were grossly distorted and their thylakoid membranes appeared to have folded over upon themselves (Fig. 3D). Chloroplasts of BS and mesophyll cells adjacent to the wound in wild-type leaves displayed a relatively normal structure (Figs. 3B and 4B).

Figure 4.

Transmission electron microscopy of mesophyll cell chloroplasts and nuclei in injured and uninjured (21 h post-pinprick wounding) wild-type and lls1 leaves. A, Mesophyll cell chloroplasts in uninjured wild-type leaf tissue. B, Mesophyll cell chloroplasts adjoining dead cells in injured wild-type leaf tissue. C, Mesophyll cell chloroplasts in uninjured lls1 leaf tissue. Chloroplasts exhibit granal stacking (not observed in Fig. 3C). D, Mesophyll cell chloroplasts adjoining dead cells in injured lls1 leaf tissue. Chloroplasts are dramatically swollen as seen by the location of the chloroplast envelope (arrowheads). The cytoplasm is vacuolated (asterisks), although endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and Golgi (arrows) appear normal in structure. E, Portions of three mesophyll cells in injured lls1 leaf. The chloroplasts in the cell closest to the injury (asterisk) are greatly swollen. F, Fine detail of one of the chloroplasts in the adjoining cell. No other ultrastructural alterations are apparent in this cell except for the swelling visible on one of the cell's chloroplasts (arrowhead). Bars = 1 μm. C, Chloroplast; S, starch granule; M, mitochondrion; V, vacuole; R, rough endoplasmic reticulum; G, Golgi apparatus; IS, intercellular space.

A number of other fine structure changes were witnessed in mutant cells from lls1 lesions, including an increase in and marginalization of heterochromatin in BS nuclei, a frequently observed hallmark of apoptosis in animals (Figs. 3, D and F). Some increase in heterochromatin was also observed in mutant mesophyll cell nuclei, but the increase was not as great as that observed in BS nuclei (data not shown). The most common morphological change noted in plant PCD studies, namely the presence of small cytoplasmic vacuoles in dying cells, followed by cytoplasmic condensation (Bestwick et al., 1997; Kosslak et al., 1997; Mittler et al., 1997; Partington et al., 1999; Wang et al., 1999) was observed in mesophyll cells. In addition, the central vacuole seemed to have disappeared in all cells adjacent to pinprick wounds, suggesting that tonoplast collapse (Jones, 2001) may also be a feature of cell death in lls1 plants.

Extensive examination of sections taken from lls1 plants indicated that although cellular alterations discussed in the preceding paragraph do eventually emerge in all cells within lls1 lesions, they occur relatively late in the sequence of events leading to cell death. In contrast, change in chloroplast structure was not only the most conspicuous, but also the first to manifest in lls1 cells. As demonstrated in Figure 4, A and B, for mesophyll cells, swelling of the chloroplast envelope initiates well ahead of the lesion front. A similar gradient of events was witnessed with chloroplasts of mutant BS cells (data not shown). Intriguingly, mitochondria, the organelle that seems to integrate most apoptotic cell deaths in animals, maintain a normal structure even in cells displaying dramatically altered chloroplast structure (Figs. 3D and 4D; data not shown). Likewise, integrity of Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum remains unaffected in dying lls1 cells. A number of other hallmarks of apoptosis that are not witnessed in dying lls1 cells include blebbing of membranes and fragmentation of cells into vesicles (apoptotic bodies). These observations suggest that lls1 cells collapse because of a cell death process other than apoptosis.

The LLS1 Gene Is Expressed in Photosynthetic Tissues

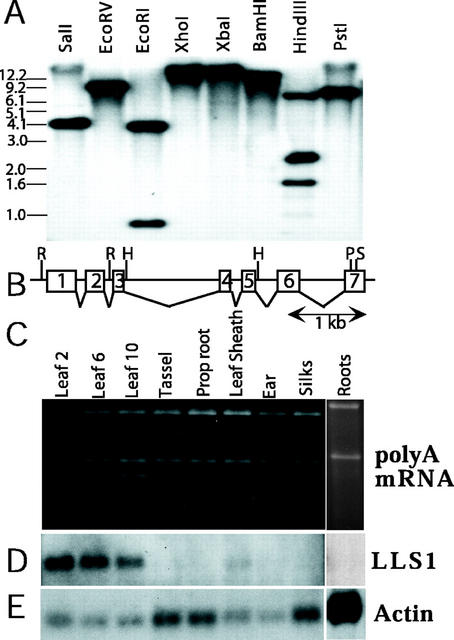

The suppression of the lls1 phenotype in non-photosynthetic tissues suggests that the product of the Lls1 gene may only be required in photosynthetic tissues. We examined various maize tissues for the presence of the Lls1 transcript. First, we determined by Southern blot that the Lls1 gene is a single-copy gene in maize as evidenced by the detection of a DNA fingerprint that is explicable by the sequence of the cloned B73 Lls1 gene alone (Fig. 5, A and B). Southern blots washed at low stringencies did not reveal any other significant cross-hybridizing bands, so we could use the Lls1 cDNA as a unique probe for northern analysis. The Lls1 message was almost undetectable in leaves when total RNA was used for northern-blot analysis (data not shown). However, using enriched poly(A+) mRNA the Lls1 transcript was readily detectable in young and old leaves of a mature B73 plant (Fig. 5D) and a low level of transcript was also detectable in the leaf sheath of plants. However, we did not detect the Lls1 message in any non-photosynthetic tissues including young tassels, silks, ear tissue, and roots. Thus, we conclude that expression of the Lls1 gene occurs mainly in the photosynthetic tissues that were demonstrated to be prone to lesion formation in mutant plants.

Figure 5.

The Lls1 gene is a single-copy gene and the Lls1 transcript is expressed in photosynthetic tissues. A, Southern-blot analysis. Maize B73 DNA was digested with the indicated enzymes, blotted, and probed with an Lls1 cDNA probe. Most lanes exhibit a single band and those with multiple bands are explicable by multiple restriction sites in the B73 structural gene. Size standards are indicated in kb. B, Gene structure of the maize Lls1 gene. The intron/exon structure of the Lls1 gene was determined by comparing the sequence of the B73 genomic sequence with an Lls1 cDNA sequence. Blocks indicate exons. Restriction sites: RI, EcoRI; HIII, HindIII; PI, PstI; and SI, SalI. C, Poly(A+)-enriched RNA from the various maize tissues was subjected to northern analysis using maize Lls1 cDNA as probe. One microgram of poly(A+) RNA was loaded per lane except for root tissue, which was deliberately overloaded. Picture of ethidium bromide-stained gel shows near equal loading of samples from indicated tissues of a mature 13-leaf B73 plant. D, Northern blot showing that a unique lls1 transcript is detectable in fully photosynthetic green leaves and at a lower level in leaf sheath but not in other tissues. E, To normalize RNA loading, the blot was stripped and rehybridized with a maize actin probe. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

LLS1 Is Most Closely Related to Other Chloroplast and Cyanobacterial Proteins Containing Non-Heme Iron-Binding Motifs

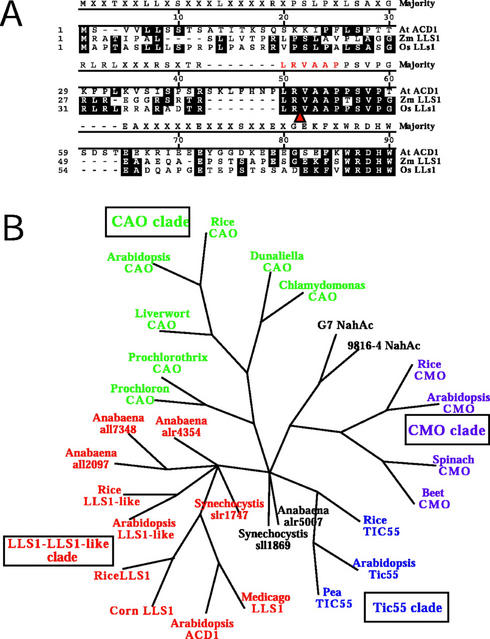

Examination of the LLS1 amino acid sequence and that of its Arabidopsis ortholog ACD1 (J. Gray, unpublished data) reveals that even though these proteins have high 72% overall amino acid identity, they exhibit weak homology at the amino terminus (Fig. 6A). However, using the algorithm ChloroP algorithm (Emanuelsson et al., 1999), both of these proteins are predicted to contain a conserved chloroplast transit-peptide cleavage site (Fig. 6A), suggesting that these proteins are targeted to the chloroplast.

Figure 6.

Predictive targeting of LLS1 to chloroplast and phylogenetic comparison of LLS1 with non-heme Fe-binding proteins from bacteria and plants. A, Alignment of amino termini of LLS1 and ACD1 proteins shows low conservation of sequence in this region. Arrow indicates the conserved cleavage site for a chloroplast transit peptide as predicted using the ChloroP algorithm. B, Cladogram of consensus tree obtained from maximal parsimony bootstrap analysis using the indicated proteins as operational taxonomic units. The consensus tree reconstructs the evolutionary relationship between LLS1 and other non-heme Fe-binding proteins. The proteins are labeled by species name or bacterial strain number in which they are found (for accession nos. and biocomputational methods, see “Materials and Methods”). Clades of related proteins are color shaded as follows: red, LLS1 and LLS1-like homologs in various plants and cyanobacteria; black, bacterial ring hydroxylating enzymes; purple, plant choline monooxygenase (CMO) enzymes; green, plant and cyanobacterial chlorophyll a oxygenase CAO enzymes; blue, pea (Pisum sativum) TIC55 Rieske Fe-sulfur protein putatively associated with transport through inner chloroplast membrane and related plant proteins.

The LLS1/ACD1 proteins contain two conserved functional motifs, a Rieske Fe-sulfur coordinating center and a non-heme mononuclear Fe-binding site. Previously, we identified these motifs only in bacterial aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases, which catalyze the opening of a phenolic ring (Gray et al., 1997). A survey of the complete Arabidopsis genome indicates that there are a total of five Arabidopsis proteins that contain the same two motifs and four of these plant genes have now been cloned and studied. In addition to ACD1, these genes include Cmo (choline monooxygenase), involved in the production of the osmoprotectant betaine (Rathinasabapathi et al., 1997); Cao (chlorophyll a oxygenase), involved in the conversion of chlorophyll a to chlorophyll b (Tanaka et al., 1998); and Tic55, which codes for a 55-kD product suspected to be involved in the translocation of proteins to the inner chloroplast membrane (Caliebe et al., 1997). The last is an lls1-like gene on chromosome 4 (see below). Because CMO and CAO are definitely not involved in phenolic metabolism, questions can be raised as to whether the function of LLS1 would be to degrade a phenolic substrate. A phylogenetic comparison between these proteins indicates that the LLS1 protein is not a clear homolog of any of these plant proteins (Fig. 6B). In Arabidopsis, there are genes more homologous to CMO and CAO and these are distinct from the Lls1 ortholog Acd1 (Fig. 6B; J. Gray and S. Reinbothe, unpublished data). In rice (Oryza sativa) and Arabidopsis, we have identified another gene (lls1-like) that is more closely related to Lls1 than Cao, Cmo, or Tic55. The LLS1-LLS1-like clade also contains several open reading frames from the cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, which have as yet unidentified functions. Only two bacterial phenolic dioxygenases are included in this analysis and these clustered in the CMO clade. Other bacterial dioxygenases proved to be more distantly related than any of the proteins included here and were omitted from this cladogram. Our earlier study indicated that the relationship between LLS1 and these bacterial phenolic dioxygenases is strictly limited to the regions containing the Fe-binding motifs (Gray et al., 1997).

The LLS1-LLS1-like clade appears to be phylogenetically equidistant from the CMO, CAO, and TIC55 clades, suggesting that in plants these two Fe-binding motifs have been recruited toward diverse metabolic functions. Another important feature of this analysis is that of all of the plant proteins known to possess these particular motifs (CAO, CMO, and TIC55) are known to be localized to the chloroplast or they are closely related to genes found in cyanobacteria—which in turn are related to the ancestral chloroplast endosymbiont. Together, these observations lend support to the proposition that LLS1 evolved to provide its positive homeostatic function within the chloroplast.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies on lls1 demonstrated that the developmentally specified phenotype of this mutation results from a cell death program that manifests intracellularly in a cell-autonomous manner (Johal et al., 1995; Gray et al., 1997; Simmons et al., 1998). The work presented here provides insights into factors and mechanisms that mediate the initiation and propagation of lls1 lesions and the nature of cellular events that result in the demise of an lls1 cell.

Loss of Chloroplast Structural Integrity Is a Key Event in lls1 Cell Death

A key finding of this study is that the loss of structural integrity of chloroplasts is the most conspicuous feature of dying lls1 cells, and the swelling of this organelle appears to be the first discernible structural event that takes place in mesophyll cells before they die. Chloroplast swelling reflects the loss of differential permeability of its envelope membranes and may result from changes occurring within the chloroplast such as photooxidation, a change in pH, or a loss of energy production (Wise and Cook, 1998; Mostowska, 1999). An intriguing difference was noticed in the way lls1 affected chloroplasts of the two cell types of the maize leaf. Although grossly disorganized, there was less evidence of chloroplast swelling in the BS cells of lls1 leaves. This may be because of the differential sensitivities of the chloroplast types to ROS or a differential ability of the BS chloroplasts to produce ROS because they lack the oxygen-generating PSII found in mesophyll chloroplasts (Pfuendel and Meister, 1996; Kingston-Smith and Foyer, 2000). Lower ROS production could result in less damage to BS cells and this could explain why the autocatalytic spread of lls1 lesions is retarded near vascular elements.

In animals, mitochondrial membrane changes resulting in mitochondrial swelling have been noted in apoptotic cells that aid the generation of ROS and in the release of a number of apoptogenic factors (such as cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor) from the intermembrane space of mitochondria to the cytosol (Hengartner, 2000; Simon et al., 2000; Von Ahsen et al., 2000). It is tempting to think that similar cell death promoting factors may be released in a parallel fashion from chloroplasts although so far none have been identified. Distortion of the chloroplast has been reported in other plant cell deaths (Mou et al., 2000), but the timing of such change has not been established and it may be a late event. In this study, however, we document that this change is an early and apparently causal event in the cell death process.

LLS1 Suppresses Spread of Cell Death Initiated by Multiple Biotic and Abiotic Factors

We found that lls1 lesions can be triggered by cellular damage inflicted by a number of agents such as pathogen ingress, physical wounding, and metabolic disorder caused by another genetic lesion. The convergence of multiple triggers, inducing lls1 cell death, might be explained if lls1 cells are predisposed to damage because a cell compartment such as the chloroplast is already compromised and sensitized toward a common cell death mediator. One class of candidates that fits well in this role are ROS, which are known to act as partly diffusible stress signals during diverse provocations in plants, including HR, lesion mimicry, and wounding (Hippeli et al., 1999; Jabs, 1999; Kliebenstein et al., 1999; Mittler et al., 1999; Heath, 2000). For example, loss-of-function mutations of the Arabidopsis Lsd1 fail to up-regulate superoxide dismutases in response to salicylic acid signaling. Failure to detoxify accumulating superoxide gives rise to propagative lesions similar to the maize lls1 mutation (Kliebenstein et al., 1999). In contrast to lls1, however, lsd1 lesions cannot be induced by mechanical wounding, indicating different modes of location or operation for the gene products. It may be that LLS1, like LSD1, is also suppressing the production or action of ROS but it may operate more directly and in a specific cell compartment such as the chloroplast.

Propagation of Cell Death in lls1 Lesions Is Light Dependent

Although a cellular injury is required for initiation of an lls1 lesion, its enlargement exclusively depends on the availability of light. The data with light filters and albino-sectored plants indicate that only light above a certain fluence rate that is captured by green photosynthetic tissue is driving the expression of lls1 lesions. Light is known to exacerbate cell death in plants and this has been documented in the case of HR, in many lesion mimic mutations (below), in barley (Hordeum vulgare) aleurone cells, and in fumonisin-induced cell death in Arabidopsis (Jabs et al., 1996; Hu et al., 1998; Mock et al., 1998; Shirasu and Schulze-Lefert, 2000; Stone et al., 2000; Mach et al., 2001). One way that cell death is promoted is through the production of free radicals by light (Hippeli et al., 1999; Jabs, 1999). For instance, in the case of Les22 plants, the production of excess porphyrin free radicals is the precipitating cause of cell death (Hu et al., 1998; Mock et al., 1998). Similarly, in acd2 plants, it is the photo-activation of the red chlorophyll catabolite that triggers free radical production and subsequent cell death (Mach et al., 2001). The fact that lls1 lesions do not develop in cells lacking chlorophyll is consistent with the idea that death of lls1 cells occurs in a similar fashion. The inability to remove photo-activatable chlorophyll intermediates could explain the developmentally regulated and wound-induced formation of lesions only in green tissue. Support for this interpretation is also reflected in the reduction of the lls1 phenotype in chlorophyll-deficient lls1/Oy and lls1/ij double mutants. Inability to remove photo-activated pigments could also result in the autocatalytic production of ROS and such an event is compatible with the observation that the signal causing propagation of lls1 lesions is somewhat diffusible (Johal et al., 1995; Dangl et al., 1996).

LLS1 Is Most Closely Related to Chloroplast and Cyanobacterial Proteins

Because chloroplast structural alterations appear to be an early feature of lls1 cell death, it is likely that chloroplasts are the primary site of action of LLS1. The fact that we could detect the Lls1 transcript only in photosynthetic tissue supports this proposition. We also found that the LLS1 protein and the dicot ortholog from Arabidopsis (ACD1) are both predicted to contain a conserved chloroplast transit peptide cleavage site. The LLS1 gene itself is highly conserved in all plant species examined thus far and the LLS1 protein is closely related to four other plant proteins that are known to function in the chloroplast. None of these are known to be involved in phenolic metabolism, which weakens our original hypothesis that LLS1 might remove a phototoxic phenolic compound (Gray et al., 1997). An alternative possibility is that LLS1 catalyzes the removal of another photosensitive metabolite (chlorophyll?) or regulates such a process by virtue of the redox-sensing Fe-binding motifs that it contains. Our phylogenetic comparison suggests that the LLS1-related plant proteins have been recruited toward diverse metabolic functions but these functions appear restricted to the chloroplast compartment and may have evolved from ancestral endosymbiont genes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we present evidence to show that LLS1 functions in plants to protect the integrity of the chloroplast compartment after biotic or abiotic stress. In the absence of this protective function, light energy is used directly or indirectly to produce a cell death mediator (possibly ROS or a phototoxic chlorophyll intermediate) that damages the chloroplast. Chloroplast destabilization then plays a central role in precipitating propagative cell death because leakage of these cell death mediators triggers death in neighboring photosynthetic cells. The protective function of LLS1 may have evolved in ancestral cyanobacteria and is conserved now in all photosynthetic organisms. We believe that whether or not chloroplast dysfunction is regulated during PCD events, it will be a useful model for reexamining other forms of rapid cell death in plants, particularly those that occur in photosynthetic tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

The reference allele for lls1 was obtained from the Maize Genetics Cooperation Stock Center (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign). The NCS2 mutation was provided by Kathy J. Newton (University of Missouri, Columbia). The oy-700 mutation was provided by Gerald Neuffer (University of Missouri, Columbia). The ij mutation was provided by Edward Coe Jr. (U.S. Department of Agriculture, University of Missouri, Columbia).

Histochemistry and Autofluorescence Microscopy

Leaves for callose studies were prepared for examination according to the method of Eschrich and Currier (1964). Leaf pieces were mounted in Moviol and examined using UV epifluorescence (excitation filter, 365 nm; dichroic mirror, 395 nm; and barrier filter, 420 nm). Captured images were color enhanced using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Whole leaf pieces were examined directly for blue light autofluorescence using a standard fluorescein isothiocyanate filter set (excitation filter, 450–490 nm; dichroic mirror, 505 nm; and barrier filter, 520 nm). Trypan blue staining was performed on fresh leaf sections as described by Yin et al. (2000), except that we stained and then destained for 12 h.

Electron Microscopy

The seventh leaves of 4-week-old wild-type (Lls1/Lls1 or Lls1/lls1) and homozygous lls1 plants were wounded via pinpricking on one side of the mid-rib. At 21 and 42 h, leaf tissue was excised at the wound and, for uninjured tissue, on the opposite side of the mid-rib. Two wild-type and two lls1 plants were examined at both time points. Tissue was excised under and fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 100 mm sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 6.9) for 2.5 h at 4°C. Tissue samples were postfixed for 2 h in 1% (w/v) OsO4 and 100 mm sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 6.9). The tissues were then stained en bloc in 2% (w/v) aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 h, washed in deionized, distilled water, and dehydrated through an ethanol series. After infiltration through a graded propylene oxide/Spurr's epoxy resin series, the tissues were embedded in 100% (w/v) Spurr's epoxy resin and polymerized at 60°C for 24 h. Ultrathin sections were prepared using a diamond knife on an 8800 Ultratome III (LKB Instruments, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The stained sections were examined on a JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd., Akishima, Japan). Images were recorded on 4489 film (Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, NY). The statistical significance of variations in the number of starch granules per chloroplast was performed by applying a Student t test analysis (two tailed, unpaired) on 11 mutant and 26 normal chloroplasts images, respectively.

Southern- and Northern-Blot Analyses

DNA was isolated from B73 maize (Zea mays) leaf tissue using a cetyltrimethylammoniumbromide-based method (Hulbert and Bennetzen, 1991). Southern-blot analysis was performed essentially as described by Gardiner et al. (1993) and the blot hybridized using a partial Lls1 cDNA clone (pJG200) as a probe. Tissue for RNA isolation was frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground to a fine powder, and added to premeasured denaturation and extraction solution (2.0 m guanidine thiocyanate, 0.6 m ammonium thiocyanate, 0.2 m sodium acetate [from 2 m stock, pH 4.0], 8% [w/v] glycerol, and 50% [w/v] phenol [water saturated, pH 4.3 ± 0.3]). Samples were vortexed and organic phase separation was effected by the addition of 0.2 volumes of chloroform per volume of extraction solution employed. RNA was isopropanol precipitated from the aqueous phase, washed with 70% (w/v) ethanol, and resuspended in RNAase-free water. Poly(A+)-enriched RNA was isolated from total RNA samples using oligo(dT)-cellulose [MicroPoly(A) Pure Kit, Ambion, Austin, TX]. RNA samples were subjected to northern-blot analysis using a 50% (w/v) formamide hybridization solution (Ausubel et al., 1994). The same cDNA probe as above was used to detect the maize lls1 transcript.

Analysis of Light Requirement for lls1 Lesion Development

To determine the spectral range of light required for lesion formation, sections of leaves were clamped between 0.125-inch plexiglas GM filters held in place by a metal stand with a side arm clamp. The following transparent filters were used: plexiglas GM 2,423 (red), 2,711 (far red), 2,424 (blue), 2,092 (green), 2,208 (yellow), and 2,422 (amber) or clear (Cope Plastics Inc., St. Louis). Transmission spectra of filters were determined by examining small sections of filters in a spectrophotometer. Leaf sections of greenhouse or field-grown plants were covered in aluminum foil to completely reflect incident light. After complete lesioning of a leaf, filters were removed to observe if lesioning had occurred in the covered region. For the estimations of lesion densities in lls1, Les, and Oy/+ leaves, the leaves were photographed side by side and lesion density expressed per unit area2 of these photographs. The numbers of lesions were counted in equivalent regions along the length of lesioned leaves or similar developmental age and averaged.

Biocomputational Methods and Data Sources

The amino acid sequences of 28 listed enzymes (below) were predicted from available GenBank files. The neighborhood search algorithm BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) was employed for database searches using the World Wide Web BLAST servers of the National Center for Biotechnology Information and The Arabidopsis Information Resource. In addition, rice (Oryza sativa) genomic sequences were retrieved from the Rice Genome Database (http://210.83.138.53/rice/) and from the Syngenta Torrey Mesa Research Institute rice genome project (http://portal.tmri.org/rice/). The ChloroP (Emanuelsson et al., 1999) algorithm was employed to predict the cellular localization of proteins. The entire proteins were aligned using with the ClustalV method with PAM250 residue weights within the MegAlign program (DNAStar, Madison, WI). Unrooted cladograms were generated by using the PAUP 4.0b10 program (Swofford, 2001). The bootstrap method was performed for 100 replicates with a maximum parsimony criterion. All characters were weighted equally. Starting trees were obtained by random stepwise addition and the tree-bisection-reconnection algorithm was used for branch swapping.

Accession Numbers

Accession numbers used for the CMO (choline monooxygenase) clade are as follows: Arabidopsis CMO precursor, T08550; spinach (Spinacia oleracea) CMO, T09214; beet (Beta vulgaris) CMO precursor, T14542; and rice CMO, AAAA00000000 (contig no. 180). Accession numbers used for the CAO (chlorophyll a oxygenase, chlorophyll b synthase) clade are as follows: Arabidopsis CAO (Arabidopsis), AAD54323; rice CAO, AAAA00000000 (contig no. 19995; Yu et al., 2002), AC087599, D48708, BAA82479, and AB021310; Dunaliella salina CAO, BAA82481; Chlamydomonas reinhardii CAO, BAA33964; liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha) CAO, BAA82480; Prochloron didemni CAO, BAA82483; and Prochlorothrix hollandica CAO, BAA82482. Accession numbers used for the LLs1 and LLs1-like clade are as follows: maize LLS1 lethal leaf-spot 1, U77346 (genomic clone pJG201) and AAC49676 (partial cDNA clone pJG200; Gray et al., 1997); Arabidopsis ACD1 accelerated cell death 1 (Lls1 ortholog), AL391254, protein identification CAC03538.1; Rice LLS1 homolog, AAAA00000000 (contig no. 6404 and Syngenta contig no. CLB11460.2, http://portal.tmri.org/rice/; Goff et al., 2002); Medicago truncatula LLS1 homolog, contig of overlapping expressed sequence tags AW257191, BE248884, BE249137, BF005787, BF633506, BF634038, BF634446, BF636009, and BF642558; Arabidopsis LLS1-like gene L73G19.30, AL050400; Anabaena sp. alr4354 LLs1-like homolog (Nostoc sp. PCC 7120), NP 488394; Anabaena sp. alr7348 LLs1-like homolog (Nostoc sp. PCC 7120), NP 490454; Anabaena sp. alr2097 LLs1-like homolog (Nostoc sp. PCC 7120), NP 486137; and Anabaena sp. alr5007 LLs1-like homolog (Nostoc sp. PCC 7120), NP 489047. Accession numbers used for the Tic55 clade are as follows: pea (Pisum sativum) TIC55 (55-kD Rieske [2Fe-2S] Fe-sulfur protein putatively associated with transport through inner chloroplast membrane), AC006585; Arabidopsis TIC55 homolog, AC006585 and contig of overlapping expressed sequence tags AI995341, AV439633, AV442063, BE038210, BE528579, and protein identification AAD23030.1; and rice TIC55 homolog, AAAA00000000 (contig no. 29820). Accession numbers used for other sequences are as follows: G7 NahAc naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase Fe-sulfur oxygenase component large chain, Pseudomonas putida (strain G7), JN0644; 9816-4 NahAc naphthalene dioxygenase ISP alpha subunit (Pseudomonas sp.), AAA92141; Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 slr1747 hypothetical protein, BAA17786.1; and Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 sll1869 hypothetical protein putative 3-chlorobenzoate-3,4-dioxygenase, BAA18227.

Distribution of Materials

Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes, subject to the requisite permission from any third party owners of all or parts of the material. Obtaining any permissions will be the responsibility of the requestor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All electron microscopy work was carried out at the Electron Microscopy Core Facility (University of Missouri, Columbia). The authors wish to acknowledge Cheryl Jensen (Electron Microscopy Core Facility) for thin sectioning all samples used in the study. The electron microscopy work described in this manuscript was carried out by D.J.-B. and B.B. while they were on sabbatical leave in the laboratory of G.S.J. in the Department of Agronomy at the University of Missouri (Columbia). The authors thank Stephen Goldman (University of Toledo, Plant Science Growth Center) for the use of facilities used for some of the analysis in this research. We thank Yang Manli (University of Toledo) for technical assistance in microscopic analysis.

Footnotes

Major funding for this work was provided by the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB–9729608 to G.S.J.), and minor funding provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (grant no. 2000–01465 to J.G.) and by The University of Toledo (laboratory startup funds to J.G.). This is journal paper no. 16,872 of the Purdue University Agricultural Research Programs.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.008441.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aist JR, Gold RE, Bayles CJ, Morrison GH, Chandra S, Israel HW. Evidence that molecular components of papillae may be involved in ml-o resistance to barley powdery mildew. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1988;33:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E, Lipman D. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bestwick CS, Brown IR, Bennett MHR, Mansfield JW. Localization of hydrogen peroxide accumulation during the hypersensitive reaction of lettuce cells to Pseudomonas syringae pv phaseolicola. Plant Cell. 1997;9:209–221. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Petersen M, Pike HM, Olszak B, Skov S, Odum N, Jorgensen LB, Brown RE, Mundy J. Knockout of Arabidopsis ACCELERATED-CELL-DEATH11encoding a sphingosine transfer protein causes activation of programmed cell death and defense. Genes Dev. 2002;16:490–502. doi: 10.1101/gad.218202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner B, Johal GS, Janick-Buckner D. Cell death in maize. Physiol Plant. 2000;108:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Büschges R, Hollricher K, Panstruga R, Simons G, Wolter M, Frijters A, Van Daelen R, Van Der Lee T, Diergarde P, Groenendijk J et al. The barley Mlo gene: a novel control element of plant pathogen resistance. Cell. 1997;88:695–705. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliebe A, Grimm R, Kaiser G, Lubeck J, Soll J, Heins L. The chloroplastic protein import machinery contains a Rieske-type iron-sulfur cluster and a mononuclear iron-binding protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:7342–7350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N, Drake J, Ayliffe M, Sun Q, Ellis J, Hulbert S, Pryor T. Molecular characterization of the maize Rp1-Drust resistance haplotype and its mutants. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1365–1376. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Dietrich RA, Richberg MH. Death don't have no mercy: cell death programs in plant-microbe interactions. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1793–1807. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto A, Piffanelli P, Nilsson I, Wallin E, Panstruga R, von Heijne G, Schulze-Lefert P. Topology, subcellular localization, and sequence diversity of the Mlo family in plants. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34993–35004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich RA, Delaney TP, Uknes SJ, Ward ER, Ryals JA, Dangl JL. Arabidopsis mutants simulating disease resistance response. Cell. 1994;77:565–577. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, von Heijne G. ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Prot Sci. 1999;8:978–984. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.5.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschrich W, Currier HB. Identification of callose by its diachrome and flourochrome reactions. Stain Technol. 1964;39:303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner JM, Coe EH, Melia-Hancock S, Hoisington DA, Chao S. Development of a core RFLP map in maize using an immortalized F2 population. Genetics. 1993;134:917–930. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan T-H, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativaL. ssp. japonica) Science. 2002;296:92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J, Close PS, Briggs SP, Johal GS. A novel suppressor of cell death in plants encoded by the Lls1gene of maize. Cell. 1997;89:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J, Johal GS. Programmed cell death in plants. In: Anderson M, Roberts J, editors. Arabidopsis. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press; 1998. pp. 360–394. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JT. Programmed cell death in plant-pathogen interactions. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:525–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JT, Ausubel FM. Arabidopsis mutants compromised for the control of cellular damage during pathogenesis and aging. Plant J. 1993;4:327–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.04020327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haecker G. The morphology of apoptosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:5–17. doi: 10.1007/s004410000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones JDG. Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1773–1791. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han CD, Coe EH, Martienssen RA. Molecular cloning and characterization of iojap (ij), a pattern striping gene of maize. EMBO J. 1992;11:4037–4046. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath MC. Hypersensitive response-related death. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;44:321–334. doi: 10.1023/a:1026592509060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippeli S, Heiser I, Elstner EF. Activated oxygen and free oxygen radicals in pathology: new insights and analogies between animals and plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1999;37:167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Richter TE, Hulbert SH, Pryor T. Disease lesion mimicry caused by mutations in the rust resistance gene rp1. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1367–1376. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.8.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Yalpani N, Briggs SP, Johal GS. A porphyrin pathway impairment is responsible for the phenotype of a dominant disease lesion mimic mutant of maize. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1095–1105. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.7.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert SH, Bennetzen JL. Recombination at the Rp1locus of maize. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:377–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00260649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa A, Okamoto H, Iwasaki Y, Asahi T. A deficiency of coproporphyrinogen III oxidase causes lesion formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2001;27:89–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs T. Reactive oxygen intermediates as mediators of programmed cell death in plants and animals. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:231–245. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs T, Dietrich RA, Dangl JL. Initiation of runaway cell death in an Arabidopsis mutant by extracellular superoxide. Science. 1996;273:1853–1856. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johal GS, Briggs SP. Reductase activity encoded by the HM1 disease resistance gene in maize. Science. 1992;258:985–987. doi: 10.1126/science.1359642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johal GS, Hulbert S, Briggs SP. Disease lesion mimics of maize: a model for cell death in plants. Bioessays. 1995;17:685–692. [Google Scholar]

- Johal GS, Lee EA, Close PS, Coe EH, Neuffer MG, Briggs SP. A tale of two mimics: transposon mutagenesis and characterization of two disease lesion mimic mutations of maize. Maydica. 1994;39:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jones AM. Programmed cell death in development and defense. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:94–97. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston-Smith AH, Foyer CH. Bundle sheath proteins are more sensitive to oxidative damage than those of the mesophyll in maize leaves exposed to paraquat or low temperatures. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Dietrich RA, Martin AC, Last RL, Dangl JL. LSD1 regulates salicylic acid induction of copper zinc superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1999;12:1022–1026. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.11.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga H, Zeyen RJ, Bushnell WR, Ahlstrand GG. Hypersensitive cell death, autofluorescence, and insoluble silicon accumulation in barley leaf epidermal cells under attack by Ersiphe graminis f. sp. hordei. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1988;32:395–409. [Google Scholar]

- Kosslak RM, Chamberlin MA, Palmer RG, Bowen BA. Programmed cell death in the root cortex of soybean root necrosis mutants. Plant J. 1997;11:729–745. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11040729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach JM, Castillo AR, Hoogstraten R, Greenberg JT. The Arabidopsis-accelerated cell death gene ACD2 encodes red chlorophyll catabolite reductase and suppresses the spread of disease symptoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:771–776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021465298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majno G, Joris I. Apoptosis, oncosis, and necrosis. An overview of cell death. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marienfeld JR, Newton KJ. The maize NCS2 abnormal growth mutant has a chimeric nad4-nad7mitochondrial gene and is associated with reduced complex I function. Genetics. 1994;138:855–863. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Herr EH, Orvar BL, van Camp W, Willekens H, Inzé D, Ellis BE. Transgenic tobacco plants with reduced capability to detoxify reactive oxygen intermediates are hyperresponsive to pathogen infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14165–14170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Simon L, Lam E. Pathogen-induced programmed cell death in tobacco. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1333–1344. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock HP, Keetman U, Kruse E, Rank B, Grimm B. Defense responses to tetrapyrrole-induced oxidative stress in transgenic plants with reduced uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase or coproporphyrinogen oxidase activity. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Molina A, Volrath S, Guyer D, Maleck K, Ryals J, Ward E. Inhibition of protoporphyrinogen oxidase expression in Arabidopsis causes a lesion-mimic phenotype that induces systemic acquired resistance. Plant J. 1999;17:667–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel J-B, Dangl JF. The hypersensitive response and the induction of cell death in plants. Cell Death Diff. 1997;4:671–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SW, Vernooij B, Titatarn S, Starrett M, Thomas S, Wiltse CC, Frederiksen RA, Bhandhufalck A, Hulbert S, Uknes S. Induced resistance responses in maize. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:643–658. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.7.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostowska A. Response of chloroplast structure to photodynamic herbicides and high oxygen. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 1999;54:621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Mou Z, He Y, Dai Y, Liu X, Li J. Deficiency in fatty acid synthase leads to premature cell death and dramatic alterations in plant morphology. Plant Cell. 2000;12:405–417. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuffer MG, Coe EH, Wessler SR. Mutants of Maize. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. Gene descriptions; pp. 211–301. [Google Scholar]

- Partington JC, Smith C, Bolwell GP. Changes in the location of polyphenol oxidase in potato (Solanum tuberosumL.) tuber during cell death in response to impact injury: comparison with wound tissue. Planta. 1999;207:449–460. doi: 10.1007/s004250050504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfuendel E, Meister A. Flow cytometry of mesophyll and bundle sheath chloroplast thylakoids of maize (Zea maysL.) Cytometry. 1996;23:97–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19960201)23:2<97::AID-CYTO2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacco ML, Walden DB. Genetic, developmental, and environmental influences on Oy-700 expression in maize. J Hered. 1987;78:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rate DN, Cuenca JV, Bowman GR, Guttman DS, Greenberg JT. The gain-of-function Arabidopsis acd6 mutant reveals novel regulation and function of the salicylic acid signaling pathway in controlling cell death, defenses, and cell growth. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1695–1708. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.9.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinasabapathi B, Burnet M, Russell BL, Gage DA, Liao P-C, Nye GJ, Scott P, Golbeck JH, Hanson AD. Choline monooxygenase, an unusual iron-sulfur enzyme catalyzing the first step of glycine betaine synthesis in plants: prosthetic group characterization and cDNA cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3454–3458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu K, Schulze-Lefert P. Regulators of cell death in disease resistance. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;44:371–385. doi: 10.1023/a:1026552827716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons C, Hantke S, Grant S, Johal GS, Briggs S. The maize lethal leaf spot1mutant has elevated resistance to fungal infection at the leaf epidermis. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;472:1110–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Simon H-U, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis. 2000;5:415–418. doi: 10.1023/a:1009616228304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JM, Heard JE, Asai T, Ausubel FM. Simulation of fungal-mediated cell death by fumonisin B1 and selection of fumonisin B1-resistant (fbr) Arabidopsis mutants. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1811–1822. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Collins NC, Ayliffe M, Smith SM, Drake J, Pryor T, Hulbert SH. Recombination between paralogues at the rp1rust resistance locus in maize. Genetics. 2001;158:423–438. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A, Ito H, Tanaka R, Tanaka N, Yoshida K, Okada K. Chlorophyll a oxygenase is involved in chlorophyll b formation from chlorophyll a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12719–12723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D, Walbot V, Coe EHJ. Plastid development in iojap- and chloroplast mutator-affected maize plants. Am J Bot. 1983;70:940–950. [Google Scholar]

- Ullstrup AJ, Troyer AF. A lethal leaf spot of maize. Phytopathology. 1967;57:1282–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Von Ahsen O, Waterhouse NJ, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. The “harmless” release of cytochrome c. Cell Death Diff. 2000;7:1192–1199. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walbot V, Hoisington DA, Neuffer MG. Disease lesion mimic mutations. In: Kosuge T, Meredith CP, Hollaender A, editors. Genetic Engineering of Plants. New York: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1983. pp. 431–442. [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Hoekstra S, van Bergen S, Lamers GEM, Oppedijk BJ, van der Heijden MW, de Priester W, Schilperoort RA. Apoptosis in developing anthers and the role of ABA in this process during androgenesis in Hordeum vulgareL. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;39:489–501. doi: 10.1023/a:1006198431596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RR, Cook WB. Development of ultrastructural damage to chloroplasts in a plastoquinone-deficient mutant of maize. Environ Exp Bot. 1998;40:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z, Chen J, Zeng L, Goh M, Leung H, Khush GS, Wang G-L. Characterizing rice lesion mimic mutants and identifying a mutant with broad-spectrum resistance to rice blast and bacterial blight. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:869–876. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK-S, Li S, Liu B, Deng Y, Dai L, Zhou Y, Zhang X et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativaL. ssp. indica) Science. 2002;296:79–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1068037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]