Abstract

The antimycotic clotrimazole, a potent inhibitor of the intermediate-conductance calcium-activated K+ channel, IKCa1, is in clinical trials for the treatment of sickle cell disease and diarrhea and is effective in ameliorating the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. However, inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes by clotrimazole limits its therapeutic value. We have used a rational design strategy to develop a clotrimazole analog that selectively inhibits IKCa1 without blocking cytochrome P450 enzymes. A screen of 83 triarylmethanes revealed the pharmacophore for channel block to be different from that required for cytochrome P450 inhibition. The “IKCa1-pharmacophore” consists of a (2-halogenophenyl)diphenylmethane moiety substituted by an unsubstituted polar π-electron-rich heterocycle (pyrazole or tetrazole) or a −C N group, whereas cytochrome P450 inhibition absolutely requires the imidazole ring. A series of pyrazoles, acetonitriles, and tetrazoles were synthesized and found to selectively block IKCa1. TRAM-34 (1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole) inhibits the cloned and the native IKCa1 channel in human T lymphocytes with a Kd of 20–25 nM and is 200- to 1,500-fold selective over other ion channels. Using TRAM-34, we show that blocking IKCa1 in human lymphocytes, in the absence of P450-inhibition, results in suppression of mitogen-stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation of preactivated lymphocytes with EC50-values of 100 nM-1 μM depending on the donor. Combinations of TRAM-34 and cyclosporin A are more effective in suppressing lymphocyte mitogenesis than either compound alone. Our studies suggest that TRAM-34 and related compounds may hold therapeutic promise as immunosuppressants.

Clotrimazole, a topically used antimycotic, exerts its fungicidal effect by inhibiting fungal P450-dependent enzymes (1). Clotrimazole has also been reported to inhibit mammalian P450 enzymes (2–4), as well as directly block the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (IKCa) channel, a product of the IKCa1 gene (5–7), in human erythrocytes, colonic epithelium, and human T lymphocytes at nanomolar concentrations (8–13). This lack of specificity clouds the use of clotrimazole as a pharmacological tool, creating a need for a truly selective IKCa1 inhibitor. Because of its potent channel-blocking activity, clotrimazole is being clinically evaluated for the treatment of erythrocyte dehydration in sickle cell disease and secretory diarrheas (9, 14). Recent studies have also raised the possibility of using clotrimazole as an immunosuppressant (12, 13). Clotrimazole was previously reported to be effective in rheumatoid arthritis (15). However, the gastrointestinal and urinary disturbances caused by clotrimazole, coupled with elevation of hepatic enzymes (9, 16) and changes in plasma cortisol levels (15) caused by its acute inhibition (2–4) and chronic induction of human P450-dependent enzymes (3, 17), may limit its systemic use (18).

Resting human T lymphocytes possess ≈400 Kv1.3 channels and roughly 2–20 functional IKCa1 channels. The membrane potential of resting T cells is maintained by Kv1.3 channels rather than by IKCa1, and selective inhibitors of Kv1.3 suppress the activation response (19). In contrast, mitogen-activated human T lymphocytes exhibit 300–800 functional IKCa1 channels (20) along with 400–500 Kv1.3 channels. Because expression of IKCa1 channels is dramatically enhanced in activated T cells (20), in parallel with enhanced [Ca2+]i signaling (21, 22), a strategy targeting IKCa1 channels could be especially effective in suppressing chronically activated T cells and could perhaps lead to therapy for autoimmune disorders.

By identifying and exploiting differences in the pharmacophores required for channel block and cytochrome P450 inhibition, we have designed a triarylmethane (TRAM-34) that selectively blocks the IKCa1 channel. TRAM-34 may have a therapeutic profile similar to clotrimazole but may lack its toxic side effects.

Materials and Methods

Compounds.

Clotrimazole (1a), econazole, and ketoconazole were purchased from Sigma. Clotrimazole was subjected to the same physical analysis as the synthesized triarylmethanes (see supplementary Table 2, www.pnas.org) to ensure its purity. Nifedipine, nimodipine, and nitrendipine were obtained from Research Biochemicals. Triarylmethanes were synthesized according to the route described for clotrimazole (23) with modifications according to ref. 24 and of our own. Compounds were characterized by melting point, IR, 1H-NMR, mass spectrometry, and combustion analysis. Briefly, triarylmethanols (2a-p) were prepared from benzophenones and aryl bromides by a Grignard reaction and then converted into triaryl chlorides with freshly distilled thionyl chloride in petroleum ether, which then were further reacted with an excess of the required amine in anhydrous acetonitrile to give compounds 1b-f, 3h-l, 4a-q, 6a-m, and 7a. Bivalent and trivalent compounds 8a-f were synthesized according to ref. 25. Compounds 3a-d were prepared from the triaryl chlorides in a mixture of diethyl ether and 25% aqueous ammonia solution (26). Compounds 3e-g were prepared by reacting 3a, 3b, and 3d with freshly distilled acetic anhydride. Compounds 3h-k were synthesized from triaryl chlorides and urea according to the method given for 8a-f. Compounds 5a-f were synthesized by heating triaryl chlorides with copper cyanide without solvent (27).

Clones, Cells, and Cell Lines.

The cloning of human IKCa1 and transient transfection into COS-7 cells have been previously reported (11). Cell lines stably expressing mKv1.1, rKv1.2, mKv1.3, mKv3.1, and hKv1.5 have been previously described (28). Human SKCa2 (expressed sequence tag: GenBank accession no. AI810558) and human SKCa3 (AJ251016), were cloned in-frame downstream to green fluorescent protein in the pEGFP-C1 expression vector (CLONTECH). Rat SKCa2 (U69882) was previously described (29). These clones were transiently expressed in COS-7 cells. LTK cells expressing hKv1.4 and rKv4.2 were obtained from M. Tamkun (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO), HEK-293 cells expressing the skeletal muscle sodium channel hSkM1 (SCN4A) from F. Lehmann-Horn (University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany), and HEK-293 cells expressing hSloα (30) from A. Tinker (Centre for Clinical Pharmacology, University College London). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from heparinized blood samples of healthy volunteers by using a lymphocyte separation medium (Accuspin System-Histopaque-1077, Sigma) and maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS/2 mM l-glutamine/1 mM Na+ pyruvate/1% nonessential amino acids/100 units/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were rested for 24 h after isolation and then activated with 10 nM phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or 5 ng/ml anti-CD3 Ab (Biomedia, Foster City, CA). T cells were isolated by nylon-wool purification immediately before electrophysiological experiments, typically yielding >90% CD3+ T cells.

Electrophysiology.

Cells were studied in the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique. The holding potential in all experiments was −80 mV. For measurement of IKCa, SKCa, and BKCa currents, we used an internal pipette solution containing (in mM): 145 K+ aspartate, 2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 K2 EGTA, and 8.5 CaCl2 (1 μM free Ca2+), pH 7.2, 290–310 mOsm. To reduce currents from the native chloride channels in COS-7, T84, and T cells, Na+ aspartate Ringer was used as an external solution (in mM): 160 Na+ aspartate/4.5 KCl/2 CaCl2/1 MgCl2/5 Hepes, pH 7.4/290–310 mOsm. IKCa currents in COS-7 and T84 cells were elicited by 200-ms voltage ramps from −120 mV to 40 mV applied every 10 s and the reduction of slope conductance at −80 mV by drug taken as a measure of channel block. For activated T lymphocytes, the same voltage ramp was applied every 30 s to avoid inactivation of Kv1.3 channels. BKCa currents were elicited by 200-ms voltage ramps from −80 to 80 mV applied every 30 s and channel block measured at 35 mV. The inward rectifier (rKir2.1) in RBL cells was studied in Na+ aspartate Ringer with a K+ aspartate-based pipette solution containing 50 nM free Ca2+. Recordings from Jurkat SKCa channels were made in K+ aspartate Ringer. For both SKCa and inward rectifier currents, the reduction of slope conductance at −110 mV was taken as measure of channel block. For all currents elicited by voltage ramps, series resistance was not used. Recordings of Kv- (28), monovalent currents through Jurkat calcium release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels (31), and swelling-activated chloride currents (32) were made as previously described.

Inhibition Studies of CYP3A4.

Inhibition of the catalytic activity of purified recombinant human cytochrome P450 3A4 in microsomes (Gentest Corporation, Woburn, MA) was assayed on the turnover of 7-benzyloxy-4-trifluoromethyl-coumarin by the detection of its fluorescent metabolite 7-hydroxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin as described (33). All experiments were done in duplicate, and results are reported as percent inhibition. Positive controls (5 μM ketoconazole and 100 nM clotrimazole) were run on the same plate producing 99% inhibition.

[3H]Thymidine Incorporation Assay.

Resting or 2-day-activated (10 nM PMA or 5 ng/ml anti-CD3 Ab) PBMCs were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in culture medium in flat-bottom 96-well plates (final volume 200 μl). Cells preincubated with drug (60 min) were stimulated with mitogen (10 nM PMA + 175 nM ionomycin or 5 ng/ml anti-CD3 Ab) for 48 h. Triated thymidine ([3H]TdR) (1 μCi per well) was added for the last 6 h. Cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters and radioactivity measured in a scintillation counter.

Flow Cytometric Measurement of Cell Viability.

Cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells/ml (Jurkat E6–1, MEL cells, human T lymphocytes) or 105 cells/ml (C2F3 myoblasts, CHO, COS-7, L929, NGP and NLF neuroblastoma, RBL-2H3) in 12-well plates. Drug (5 μM) was added in a final DMSO concentration of 0.1% which was found not to affect cell viability. After 48 h cells were harvested by suction (suspension cells) or by trypsinization (adherent cell lines), centrifuged, resuspended in 0.5 ml PBS containing 1 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI), and red fluorescence measured on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The percentage of dead cells was determined by their PI uptake, 104 cells of every sample being analyzed.

Acute in Vivo Toxicity Determinations.

Five CF-1BR mice (17–19 g) were injected intravenously with a single 1.0-ml dose of 0.5 mg/kg TRAM-34 (in mammalian Ringer solution with 1% ethanol and 2.5% BSA). Five control mice were injected with an equal volume of the vehicle. Mice were observed for adverse effects immediately after dosing, at 4 h after injection and daily for 7 days.

Results

Defining the Triarylmethane Oharmacophore for IKCa1 Block.

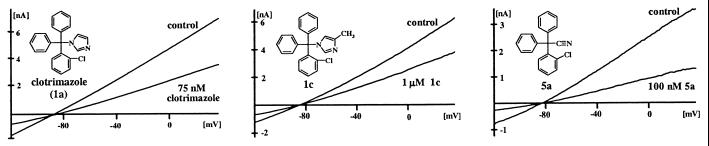

Fig. 1 shows currents from IKCa1-transfected COS-7 cells elicited by voltage ramps with 1 μM free calcium in the pipette solution. Clotrimazole (compound 1a) potently blocks the IKCa1 channel with a Kd of 70 nM. In contrast, two related antimycotic agents, ketoconazole (Kd = 30 μM) and econazole (Kd = 12 μM), as well as the dihydropyridines nifedipine (Kd = 4 μM), nimodipine (Kd = 1 μM), and nitrendipine (Kd = 0.9 μM), are significantly less potent.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory effects of compounds 1a (clotrimazole), 1c, and 5a on IKCa1 currents expressed in COS-7 cells. Voltage ramps were applied from −120 mV to 40 mV.

We synthesized 83 triarylmethanes and tested them by whole-cell patch clamp against IKCa1 channels, the compounds being added externally in every case. The structures and channel-blocking potencies of 30 exemplary compounds that highlight our design strategy are described in Fig. 2, and their physical data are listed in supplementary Table 3 (www.pnas.org). The structures and channel affinities of the remaining 53 compounds are provided in supplementary Table 3 and their physical data in supplementary Table 4. The hydrolytic stability of TRAM-34 is shown in supplementary Fig. 5.

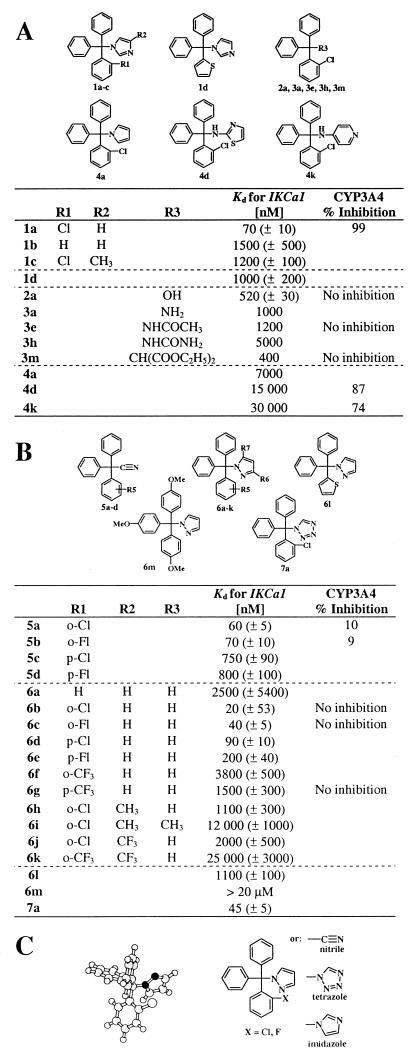

Figure 2.

(A) Structures of triarylmethanes and blocking potencies of IKCa1 and CYP3A4. Clotrimazole and compound 1a were tested at five concentrations (n = 3). Kd and Hill coefficient (Hill coefficient = 1.2) were determined by fitting the Hill equation to the reduction of slope conductance at −80 mV. The remaining compounds were screened at 100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM and their Kd values determined by fitting the data with the same Hill coefficient as clotrimazole. Inhibition of CYP3A4 was tested at 10 μM except for clotrimazole, which was tested at 100 nM. (B) Structures of triarylmethyl-acetonitriles, -pyrazoles, and -tetrazoles, and blocking potencies of IKCa1 and CYP3A4. Compound 6b was tested at five concentrations (15 cells); the other compounds were tested at three concentrations (9 cells). Hill coefficient = 1.0 to 1.2. (C) Pharmacophore for triphenylmethane IKCa1 blockers. (Left) AM1-optimized molecular structure of TRAM-34 (color code: white, hydrogen and chlorine; light gray, carbon; black, nitrogen). (Right) General structure of the pharmacophore for channel block.

To test whether the imidazole ring is necessary for channel blocking activity, we generated several analogs where this moiety is replaced by a hydroxyl- (2a-p), an amino- (3a-d), an acetamido- (3e-g), an ureido- (3h-k), a malono- (3 l), an aromatic pyrrole- (4a), an aminothiazol- (4d), or an aminopyridine- (4k) group. All these analogs are significantly less potent than clotrimazole (Fig. 2A), indicating the need of the imidazole moiety for channel block. Five bivalent compounds and one trivalent compound (supplementary Table 3, 8a-f) are inert. The triphenylmethyl moiety of the molecule is equally important for channel block, because replacement of one or more of the phenyl rings by thiophene (1c, 2 m-p) or pyrimidine (supplementary Table 3) reduces activity 10- to 20-fold (Fig. 2A). Our analysis also reveals the requirement of the o-halogen on the triphenylmethane, because imidazole analogs lacking an o-chlorine substituent (1b) are 20-fold less potent than clotrimazole (1a), whereas compounds containing more than one chlorine (2d-e, supplementary Table 3) are inert. Collectively, our data indicate that low nanomolar block of IKCa1 requires the presence of both the (2-halogenophenyl)diphenylmethane and the imidazole moieties.

Comparison of the Pharmacophores for Channel Block and Cytochrome P450 Inhibition.

Extensive structure-activity studies of azole antimycotics have shown that the imidazole ring is absolutely required for block of cytochrome P450 enzymes. These compounds exert their inhibitory effect by coordinately binding to the heme iron of P450-dependent enzymes with the N3 nitrogen of the imidazole ring (1). Replacement of the imidazole ring by other heterocyles lacking this crucial nitrogen atom abolishes inhibition and induction of cytochrome P450 enzyme activity (17, 23). To determine whether such substituents might retain potency against IKCa1, we generated a new series of analogs (Fig. 2B) where the imidazole moiety was replaced with functional groups of similar size, lipophilicity, and π-electron density, such as −C N (5a-d), pyrazole (6a-m), and tetrazole (7a). Two acetonitriles (5a, 5b), four pyrazoles (6b-e), and the tetrazole (7a) analog are potent inhibitors of IKCa1, four of these having higher affinities than clotrimazole (Fig. 2B). However, any substitution on these small heterocycles (6h-k) dramatically diminishes affinity (Kd 1–25 μM), an effect we also witnessed in the corresponding imidazole compounds (Fig. 1, Table 1, 1c, 1e, and 1f, and supplementary Table 3, www.pnas.org). As with the imidazole series, the o-halogen is required for optimal activity, because 6a lacking this group is 100-fold less effective. Ten compounds, including representative acetonitriles (5a, 5b) and pyrazoles (6b, 6k), were tested at a single high concentration of 10 μM for inhibition of the catalytic activity of recombinant human cytochrome P450 3A4, the major xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme in human liver. These compounds do not inhibit CYP3A4 activity at 10 μM, whereas clotrimazole, for which reported EC50 values vary from 250 pM (34) to 30 nM (4), completely inhibits CYP3A4 at 100 nM (Fig. 2). Thus, we have successfully separated the IKCa1-blocking activities from cytochrome P450 inhibition.

Table 1.

Selectivity

| Channel | Clotrimazole, nM | TRAM-34, nM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IKCa | IKCal | 70 ± 10 | 20 ± 3 |

| lymphocyte IK | 100 | 25 ± 5 | |

| T84 IK | 90 ± 15 | 22 ± 10 | |

| K+ | Kv1.1 | 10,000 ± 850 | 9,500 ± 1,000 |

| Kv1.2 | 5,000 ± 730 | 4,500 ± 520 | |

| Kv1.3 | 6,000 ± 440 | 5,000 ± 350 | |

| Kv1.4 | 6,000 ± 520 | 7,500 ± 410 | |

| Kv1.5 | 8,000 ± 890 | 7,000 ± 620 | |

| Kv3.1 | 33,000 ± 4,000 | 30,000 ± 5,000 | |

| Kv4.2 | 8,000 ± 950 | 6,000 ± 870 | |

| Jurkat-SK | 22,000 ± 1,200 | 23,000 ± 3,000 | |

| hSKCa2 | 21,000 ± 2,000 | 18,000 ± 3,000 | |

| rSKCa2 | >100 μM (29) | 20,000 ± 3,000 | |

| hSKCa3 | 28,000 ± 5,000 | 25,000 ± 3,000 | |

| Slo | 24,000 ± 2,000 | 25,000 ± 1,800 | |

| Kir2.1 | >20 μM | >20 μM | |

| Na+ | SKM1 | 7,000 ± 550 | 8,000 ± 600 |

| Ca2+ | Jurkat-CRAC | >20 μM | >20 μM |

| Cl− | T cell swelling-activated | not done | 10,000 ± 3,000 |

| COS-7 | >20 μM | >20 μM |

Our results suggest that optimal potency against the IKCa1 channel is achieved with a (2-halogenophenyl)diphenylmethane moiety substituted by a small unsubstituted polar π-electron-rich heterocyle (pyrazole or tetrazole) or a −C N group (Fig. 2C). Molecular modeling studies (AM1) render a propeller-shaped structure for the pharmacophore. The three phenyl rings are almost perpendicular to the central C—N bond axis between the triphenylmethane moiety and the imidazole or pyrazole ring. This modeled structure is in agreement with the crystal structure for clotrimazole (35).

TRAM-34 Is a Highly Selective Inhibitor of Cloned IKCa1 and Native IKCa Currents.

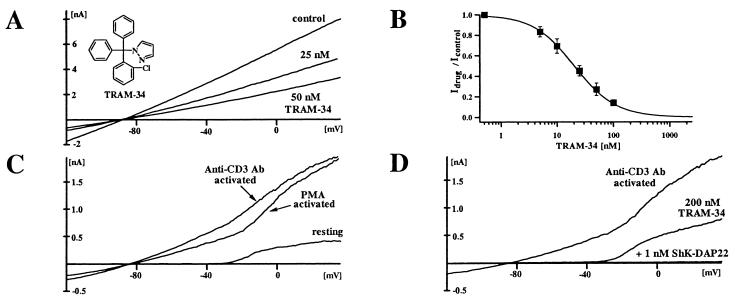

A pyrazole 1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H. pyrazole (6b, TRAM-34) was characterized further. This highly lipophilic compound (logP value of 4.0) is readily membrane permeable. Fig. 3A shows the effect of externally applied TRAM-34 on IKCa1 currents in COS-7 cells. The dose-response curve (Fig. 3B) reveals a Kd of 20 ± 3 nM and a Hill coefficient of 1.2 with 1 μM calcium in the pipette. Because the IKCa1 channel is activated by cytoplasmic calcium (half activation: ≈300 nM) via a calmodulin-dependent mechanism and is not voltage dependent (7, 11, 20), we examined whether the channel's sensitivity to block by TRAM-34 depends on the intracellular calcium concentration. The Kds measured at lower internal calcium concentrations (500 nM Ca2+ Kd = 24 ± 8 nM; 250 nM Ca2+ Kd = 28 ± 6 nM) suggest that block by TRAM-34 is not calcium dependent. The block by all triarylmethanes is voltage independent and slow in onset, taking 3–6 minutes to reach equilibrium.

Figure 3.

(A) IKCa1 currents in COS-7 cells blocked by TRAM-34. (B) Dose response for IKCa1 channel block by TRAM-34. The Hill equation was fitted to the reduction of slope conductance at −80 mV (15 cells). (C) IKCa currents in resting human T lymphocytes and in T lymphocytes activated for 2 days with PMA or anti-CD3 Ab. Mean IKCa conductance in resting cells = 0.098 (±0.17) ns (n = 24), PMA activated (10 nM) = 3.45 (±2.21) ns (n = 21), anti-CD3 Ab-activated (5 ng/ml) = 5.59 (±3.91) ns (n = 20). (D) Effect of TRAM-34 and ShK-Dap22 on K+ currents in activated T lymphocytes.

Activation of human T lymphocytes via the receptor signaling complex by anti-CD3 Ab or the PKC-dependent cascade by PMA results in a 20- to 50-fold increase in IKCa1 conductance after 48 h (Fig. 3C). Currents at potentials more negative than −40 mV are through the IKCa1 channel, whereas at more depolarized potentials, K+ currents are carried by a combination of IKCa1 and the voltage-gated K+ channel, Kv1.3. As shown in Fig. 3D, TRAM-34 selectively blocks the IKCa1 current (Kd = 25 nM), whereas the residual Kv1.3 current is blocked by the selective peptide inhibitor, ShK-Dap22 (22, 36). TRAM-34 also blocks IKCa1 currents in human T84 colonic epithelial cells with equivalent potency (Kd = 22 nM).

To test the selectivity of the compound, we screened it against a panel of 15 other channels (Table 1). TRAM-34 is 200- to 1,500-fold less effective against several related mammalian potassium channels: Kv1.1-Kv1.5, Kv3.1, Kv4.2, Kir2.1, BKCa, including the closely related cloned SKCa channels (rSKCa2, hSKCa2, hSKCa3) as well as the native SKCa in Jurkat T cells. The CRAC calcium channel, the human SKMI-sodium channel, the swelling-activated chloride channel in activated human T lymphocytes, and the native chloride channel in COS-7 cells are also insensitive to TRAM-34.

TRAM-34 Suppresses Human T Lymphocyte Activation.

Jensen et al. (13) recently showed that 10 μM clotrimazole suppresses antigen- and mitogen-induced proliferation of resting human lymphocytes. Since this concentration is ≈100 times the channel-blocking dose, suppression is probably due to a nonspecific mechanism. Studies done at the same time by Khanna et al. (12) showed that 250 nM clotrimazole (a concentration closer to the channel-blocking dose) suppresses the activation of phytohemagglutinin-preactivated T cells more effectively than the activation of quiescent cells. However, because clotrimazole blocks both IKCa1 and cytochrome P450 enzymes, the mechanism underlying this suppression remains unclear.

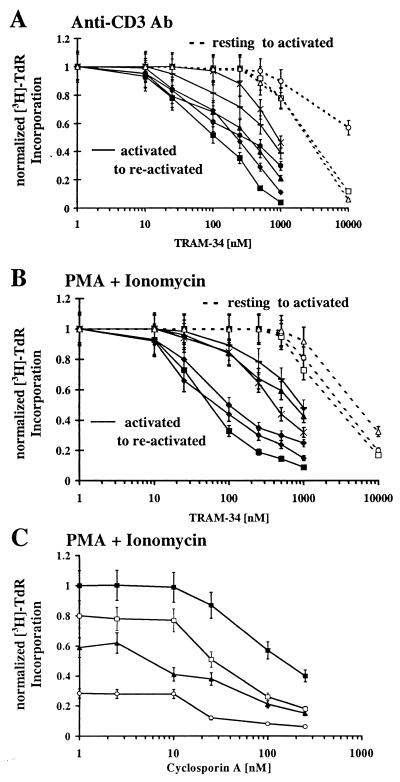

We have used TRAM-34 to evaluate the role of IKCa1 in resting and activated lymphocytes. Quiescent cells were activated for 48 h through the T-cell-receptor signaling pathway with anti-CD3 Ab or with a combination of the PKC-activator PMA and calcium-ionophore ionomycin, in the presence or absence of TRAM-34, and the incorporation of [3H]TdR measured. In parallel, cells were preactivated with either anti-CD3 Ab or PMA for 2 days to up-regulate IKCa1 channels and then restimulated with the mitogenic combinations used on quiescent cells. Up-regulated IKCa1 expression, to a level of several hundred channels in T cells preactivated by either stimulus, was confirmed in four of the six donors by whole-cell recording (n = 20/donor). In keeping with our expectations, TRAM-34 suppresses reactivation of lymphocytes by both mitogenic stimuli (Fig. 4 A and B, closed symbols). Sensitivity varies with the different stimuli and from donor to donor. In anti-CD3 Ab-stimulated T cells, the mean EC50 value among sensitive donors is 295 (±130) nM and 910 (±70) nM for less sensitive donors. In PMA + ionomycin-activated cells, including both T and B lymphocytes, the EC50 values are 85 (±30) nM for sensitive and 830 (±300) nM for less sensitive donors. In contrast, TRAM-34 has little effect at nanomolar concentrations on the activation of resting human lymphocytes and requires a dose 250–500 times the channel-blocking dose (5–10 μM) to inhibit [3H]TdR incorporation (Fig. 4 A and B, open symbols), which may be caused by nonspecific effects. Thus, our results with TRAM-34 demonstrate that selective blockade of IKCa1 channels preferentially suppresses mitogenesis in preactivated lymphocytes, in response to either PMA + ionomycin or to specific T-cell stimulation via CD3.

Figure 4.

Effect of TRAM-34 on anti-CD3 Ab- (A) or PMA + ionomycin- (B) stimulated [(3H)-TdR incorporation by resting and preactivated lymphocytes. PBMCs from different donors were activated with anti-CD3 Ab (5 ng/ml) or a combination of PMA (10 nM) + ionomycin (175 nM) for 48 h. [3H]TdR was added to the culture for the last 6 h. In parallel, PBMCs were preactivated with either anti-CD3 Ab (5 ng/ml) or 10 nM PMA for 48 h (to up-regulate IKCa1 channels) and then restimulated for a further 48 h with anti-CD3 Ab or PMA + ionomycin. Donor 1 resting (□), donor 2 resting (○), donor 3 resting (Δ), donor 1 preactivated (■), donor 2 preactivated (●), donor 3 preactivated (▴), donor 4 preactivated (♦), donor 5 preactivated [Xρ, donor 6 preactivated (−)]. (C) Effects of TRAM-34 on cyclosporin A-mediated inhibition of [(3H)-TdR incorporation. PBMCs from donor 1 were preactivated with 10 nM PMA for 48 h and then restimulated for a further 48 h with PMA + ionomycin in the presence or absence of cyclosporin A and TRAM-34. [3H]TdR was added to the culture for the last 6 h. Cyclosporin (CsA) alone (■), CsA + 250 nM TRAM-34 (□), CsA + 500 nM TRAM-34 (▴), CsA + 1 μM TRAM-34 (○).

TRAM-34 Combined with Cyclosporin A.

Cyclosporin A inhibits T-cell proliferation by acting on the calcineurin-dependent step in the activation cascade (19), whereas TRAM-34 acts on an earlier event, namely the modulation of calcium entry. A combination of the two compounds might therefore suppress mitogenesis more substantially than either compound alone. To test this idea, preactivated T cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence or absence of cyclosporin A and increasing doses of TRAM-34. The dose response for cyclosporin A-mediated suppression of [3H]TdR incorporation was shifted by TRAM-34 to more sensitive values by a factor of 2- to 10-fold for donor 1 (Fig. 4C). Similar results were obtained with donors 2 and 6 (data not shown).

TRAM-34 Is Nontoxic in an in Vitro Assay and in a Limited Short-Term Acute in Vivo Toxicity Test.

TRAM-34 (5 μM) does not reduce cell viability of human T lymphocytes or several cell lines incubated for 48 h with the compound (supplementary Table 5). Mice (n = 5) injected intravenously with a single dose of TRAM-34 (0.5 mg/kg; 29 μM) appeared clinically normal during the 7-day study. The body-weight data of the TRAM-34-treated group (day 1:17.8 g; day 7: 27.0 g) were similar to control mice injected with the vehicle (day 1: 17.4 g; day 7: 23.4 g). Collectively, data from these limited toxicity studies suggest that TRAM-34 is not acutely toxic at ≈500–1,000 times the channel-blocking dose.

Discussion

Starting with clotrimazole, an azole antimycotic that blocks both the IKCa1 channel and mammalian cytochrome P450 enzymes at nanomolar concentrations, we have developed compounds that selectively target IKCa1. The pharmacophore for channel block consists of a triphenyl moiety with an orthohalogen on one of the phenyl rings and substituted by a small unsubstituted polar π-electron-rich heterocyle (pyrazole or tetrazole) or a nitrile group (Fig. 2C). The molecular dimensions of this pharmacophore are ≈9.5 Å by 9.5Å by 8.6 Å, giving a molecular volume of 308 Å3. Smaller molecules that keep the perfect propeller shape of the molecule retain potency (5a and 5b), whereas the introduction of even small substituents such as a methyl group (6h, 6i) on the heterocycle lower potency by increasing size. Replacing the heterocycle with nonaromatic substituents (e.g., 2a, 3a, 3e, 3h) greatly reduces activity, the only exception being the nitrile group (5a, 5b) that has a π-electron density similar to imidazole (Figs. 1 and 2B). Other substitutions that alter the π-electron density in the heterocycle (6j) and/or distort the molecular shape (6k) also reduce potency. Affinity of these compounds for the channel does not correlate with their lipophilicity (supplementary Fig. 6, www.pnas.org). From these structure-activity relationships, we postulate that triphenylmethanes bind to a size-restricted pocket in the IKCa1 channel, possibly via π–π electron interactions involving the three phenyl rings and the pyrazole, tetrazole, or imidazole moiety. Another possibility is that the benzphenone phenyl groups do not participate in binding but instead serve as a scaffold, holding the π-bonded nitrogen, quaternary carbon, and ortho-halogen in place (Fig. 2C).

Clotrimazole and the related triarylmethanes, although applied externally in our studies, should readily cross the cell membrane because of their lipophilicity (clotrimazole: logP: 3.5; TRAM-34 logP: 4.0) and may interact with a site on the inner surface of the channel, possibly accounting for the slow onset of block. Consistent with this idea, an earlier study with a membrane-impermeant quaternary derivative of clotrimazole revealed an internal binding site on the IKCa1 channel (37). A molecular model of the IKCa1 inner vestibule (38) based on the KcsA crystal structure (39) contains a putative binding pocket that is lined by residues from the cytoplasmic ends of S5 and S6 and with dimensions to match the estimated size of the triphenylmethane pharmacophore.

The most potent channel inhibitor, TRAM-34 (Kd = 20 nM), exhibits a 200- to 1,500-fold selectivity for IKCa1 over Kv, BKCa, SKCa, Na, CRAC, and chloride channels, and unlike clotrimazole does not inhibit the major mammalian cytochrome P450 enzyme, CYP3A4. TRAM-34 also does not exhibit toxicity in an in vitro assay or cause obvious deleterious changes in a limited short-term acute toxicity study in rodents. [3H]thymidine incorporation assays using TRAM-34 as a selective inhibitor of IKCa1 demonstrate that the channel plays an important role in the reactivation process of human lymphocytes. IKCa1 blockers might therefore have use for the treatment of diverse autoimmune disorders in which reactivation of T lymphocytes contributes to the pathogenesis of the disease. Because TRAM-34 and cyclosporin A suppress T-cell mitogenesis more potently than either compound alone, IKCa1 blockers may be useful for combination therapy to reduce cyclosporin A toxicity. These encouraging results suggest that TRAM-34 should be further evaluated for possible therapeutic applications. TRAM-34 also has immediate value as a pharmacological tool to define the role of IKCa1 channels in human tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Luette Forrest, Ms. Chialing Wu, Elke Stoll, and Susan Häuer for their excellent technical assistance. We are also indebted to Dr. Dieter Heber for advice on chemical nomenclature, to Dr. Ulrich Girreser for NMR and mass spectrometry, to Dr. Hubert Kerschbaum for the CRAC channel experiments, and to Dr. Heiko Rauer for electrophysiological analysis of four initial compounds. This research was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants MH59222 (K.G.C.) and NS 14069 (M.D.C.) and by a fellowship grant (WU 320/1–1) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (H.W.).

Abbreviations

- CRAC

calcium release-activated Ca2+

- KCa

Ca2+-activated K+

- IKCa

intermediate-conductance KCa

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PMA

phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate

- [3H]TdR

tritiated thymidine

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Rodrigues A D, Gibson G G, Ioannides C, Parke D V. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:4277–4281. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayub M, Levell M J. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:1569–1775. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90456-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurice M, Pichard L, Daujat M, Fabre I, Joyeux H, Domergue J, Maurel P. FASEB J. 1992;6:752–758. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.2.1371482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler S M, Riley R J, Pritchard M P, Sutcliffe M J, Friedberg T, Wolf R C. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4406–4414. doi: 10.1021/bi992372u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishii T M, Silvia C, Hirschberg B, Bond C T, Adelman J P, Maylie J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11651–11656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joiner W J, Wang L Y, Tang M D, Kaczmarek L K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11013–11018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.11013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Logsdon N J, Kang J, Togo J A, Christian E P, Aiyar J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32723–32726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez J, Montero M, Garcia-Sancho J. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11789–11793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brugnara C, Gee B, Armsby C C, Kurth S, Sakamoto M, Rifai N, Alper S L, Platt O S. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1227–1234. doi: 10.1172/JCI118537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandorpe D H, Shmukler B E, Jiang L, Lim B, Maylie J, Adelman J P, de Franceschi L, Cappellini M D, Brugnara C, Alper S L. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21542–21553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanger C M, Ghanshani S, Logsdon N J, Rauer H, Kalman K, Zhou J, Beckingham K, Chandy K G, Cahalan M D, Aiyar J. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5746–5754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanna R, Chang M C, Joiner W J, Kaczmarek L K, Schlichter L C. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14838–14849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen B S, Odum N, Jorgensen N K, Christophersen P, Olesen S P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10917–10921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rufo P A, Merlin D, Riegler M, Ferguson-Maltzman M H, Dickinson B L, Brugnara C, Alper S L, Lencer W I. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3111–3120. doi: 10.1172/JCI119866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wojtulewski J A, Gow P J, Walter J, Grahame R, Gibson T, Panayi G S, Mason J. Ann Rheum Dis. 1980;39:469–472. doi: 10.1136/ard.39.5.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawyer P R, Brogden R N, Pinder R M, Speight T M, Avery G S. Drugs. 1975;9:424–447. doi: 10.2165/00003495-197509060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slama J T, Hancock J L, Rho T, Sambucci L, Bachmann K A. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1881–1892. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman A G, Rali T W, Nies A S, Taylor P. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 1990. 1169–1677. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cahalan M D, Chandy K G. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:749–756. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grissmer S, Nguyen A N, Cahalan M D. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:601–630. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess S D, Oortgiesen M, Cahalan M D. J Immunol. 1993;150:2620–2633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verheugen J A, Le Deist F, Devignot V, Korn H. Cell Calcium. 1997;21:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Büchel K H, Draber W, Regel E, Plempel M. Arneim-Forsch. 1972;22:1260–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartroli J, Alguero M, Boncompte E, Forn J. Arzneim-Forsch. 1992;42:832–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng K-K D, Hart H. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:7883–7906. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casadio S, Donetti A, Coppi G. J Pharm Sci. 1973;62:773–778. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600620514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loch G, Rieger V. Chem Ber. 1953;86:74–76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grissmer S, Nguyen A N, Aiyar J, Hanson D C, Mather R J, Gutman G A, Karmilowicz M J, Auperin D D, Chandy K G. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1227–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jäger H, Adelman J P, Grissmer S. FEBS Lett. 2000;469:196–202. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson A J, Tinker A, Clapp L H. The Physiologist. 1999;42:A7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerschbaum H, Cahalan M D. Science. 1999;283:836–839. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross P E, Garber S S, Cahalan M D. Biophys J. 1994;66:169–178. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80754-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson G L, Harkey M R, Gershwin M E, Hackman R M, Stern J S, Stressser D M. Life Sci. 1999;65:PL209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibbs M A, Kunze K L, Howold W N, Thummel K E. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:596–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song H, Shin H-S. Acta Crystallogr C. 1998;54:1675–1677. doi: 10.1107/s0108270198006386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalman K, Pennington M W, Lanigan M D, Nguyen A, Rauer H, Mahnir V, Paschetto K, Kem W R, Grissmer S, Gutman G A, et al. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32697–32707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunn P M. J Membr Biol. 1998;165:133–143. doi: 10.1007/s002329900427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rauer H, Pennington M, Cahalan M, Chandy K G. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21885–21892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle D A, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner R A, Kuo A, Gulbis J M, Cohen S L, Chait B T, MacKinnon R. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.