Abstract

White lupin (Lupinus albus) adapts to phosphorus deficiency (−P) by the development of short, densely clustered lateral roots called proteoid (or cluster) roots. In an effort to better understand the molecular events mediating these adaptive responses, we have isolated and sequenced 2,102 expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from cDNA libraries prepared with RNA isolated at different stages of proteoid root development. Determination of overlapping regions revealed 322 contigs (redundant copy transcripts) and 1,126 singletons (single-copy transcripts) that compile to a total of 1,448 unique genes (unigenes). Nylon filter arrays with these 2,102 ESTs from proteoid roots were performed to evaluate global aspects of gene expression in response to −P stress. ESTs differentially expressed in P-deficient proteoid roots compared with +P and −P normal roots include genes involved in carbon metabolism, secondary metabolism, P scavenging and remobilization, plant hormone metabolism, and signal transduction.

Phosphorus (P) is an essential macronutrient for plant growth and development that plays key roles in many processes, including energy metabolism and synthesis of nucleic acids and membranes (Raghothama, 1999). It is second only to nitrogen as the most limiting nutrient for plant growth (Bieleski, 1973; Raghothama, 1999; Vance, 2001). In many soils, low availability of P is a limiting factor in crop production (Marschner, 1995). Due to the low availability of soluble P in many ecosystems, plants have developed adaptive mechanisms that aid in the acquisition of P from soil. Strategies that lead to better uptake or acquisition include expanded root surface area through increased root growth and root hair development (Lynch and Brown, 1998; Gilroy and Jones, 2000; Williamson et al., 2001), organic acid synthesis and exudation (Dinkelaker et al., 1989; Johnson et al., 1996a; Jones, 1998; Aono et al., 2001; Massonneau et al., 2001; Sas et al., 2001), exudation of acid phosphatases (Duff et al., 1991; del Pozo et al., 1999; Gilbert et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2001), enhanced expression of phosphate transporters (Leggewie et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1998a, 1998b; Chiou et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2001), and mycorrhizal associations (Marschner and Dell, 1994; Smith et al., 1994). Strategies aimed at conserving P involve internal remobilization of P and use of alternative metabolic pathways (Theodorou et al., 1992; Theodorou and Plaxton, 1993; Plaxton and Carswell, 1999).

White lupin (Lupinus albus), a species known for its extreme tolerance for low P availability, has proven an illuminating model system for understanding plant adaptations to low P, despite its lack of mycorrhizal symbiosis. Instead, its adaptation to P deficiency (−P) is a highly coordinated modification of root development and biochemistry resulting in proteoid (or cluster) roots—short, densely clustered tertiary roots—that resemble bottlebrushes (Gardner et al., 1982, 1983; Dinkelaker et al., 1995; Johnson et al., 1996b; Neumann et al., 1999; Massonneau et al., 2001). Unlike typical lateral roots which emerge at random along the axes of primary and secondary roots (Charlton, 1983), proteoid roots develop laterals that emerge from every xylem pole within the axis, accompanied by extensive root hair growth, resulting in a more than 100-fold increased surface area (Dinkelaker et al., 1995; Skene, 2001).

Proteoid roots excrete large amounts of the organic acids citrate and malate (Marschner et al., 1986; Marschner et al., 1987; Johnson et al., 1996a, 1996b; Neumann et al., 1999; Massonneau et al., 2001), which help increase the availability of mineral-bound phosphates (Gardner et al., 1983; Dinkelaker et al., 1989) and the release of phosphates from humic substances (Braum and Helmke, 1995). Acid phosphatases that may aid in the release of organic P from soil (Tadano and Sakai, 1991; Gilbert et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2001) are excreted coincident with the exudation of organic acids from proteoid roots (Gilbert et al., 1999; Neumann et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2001). Concurrently, the expression of phosphate transporter genes is strikingly enhanced in P-starved proteoid roots (Neumann et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2001). Because of these adaptations, P uptake is greatly enhanced in proteoid root zones.

Proteoid root formation might be mediated by the coordinated expression of a number of genes. Expression of phosphate transporters (Liu et al., 2001), acid phosphatase (Gilbert et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2001), and genes related to organic acid synthesis (Massonneau et al., 2001; Penaloza et al., 2002; Uhde-Stone et al., 2003) have been reported to be induced in proteoid roots. Analysis of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) is an efficient approach for identifying large numbers of plant genes expressed during different developmental stages and in response to a variety of environmental conditions (Gyorgyey et al., 2000; Ohlrogge and Benning, 2000; White et al., 2000; Dunaeva and Adamska, 2001). In addition, once ESTs are generated, they provide a resource for transcript profiling experiments. In plants, differential profiling has successfully been used for identification and analysis of novel genes involved in diverse aspects of biotic and abiotic stress responses and in development (Girke et al., 2000; Sasaki et al., 2000; Kawasaki et al., 2001; Thimm et al., 2001).

Objectives of this research were to assess genes expressed in proteoid root formation and to analyze global gene expression in −P stress-induced proteoid roots. To achieve this goal, we: (a) identified ESTs from −P proteoid roots at two different developmental stages; (b) performed nylon filter arrays to compare gene expression in −P proteoid roots, +P and −P normal roots, and +P and −P leaves; (c) confirmed expression patterns for differentially expressed ESTs by RNA gel blots and reverse RNA gel blots; and (d) compared gene expression in +P and −P roots of Medicago truncatula by heterologous hybridization of white lupin ESTs.

RESULTS

Generation of ESTs from Early and Later Stages of Proteoid Root Development

Two cDNA libraries from proteoid roots of −P-stressed white lupin were constructed. A cDNA library of early stages of proteoid root development contained pooled RNA isolated from P-deficient roots and developing proteoid roots collected at 7 and 10 d after emergence (DAE). At 7 DAE, proteoid roots are not yet visible, so normal roots of −P-stressed plants were collected. At 10 DAE, immature proteoid roots were collected. A cDNA library of the later developmental stages of proteoid roots was generated with pooled RNA isolated from −P proteoid roots collected at 12 and 14 DAE. Average cDNA insert size was found to be approximately 1.6 kb. Single-pass 5′ sequencing resulted in 2,102 sequences of good quality with a length of at least 100 bp. Typical sequence lengths of good quality ranged from 400 to 500 bp. Of these 2,102 ESTs, 843 sequences derived from cDNA from the early developmental stages (7 and 10 DAE) and 1,259 ESTs from the library of more mature proteoid roots (12 and 14 DAE).

Functional Annotation

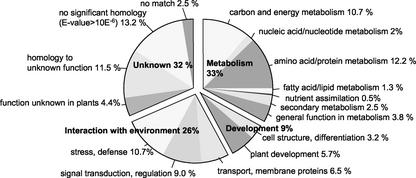

Using the BLASTX algorithm, DNA sequences were translated into their corresponding amino acid sequence and searched against the nonredundant protein database GenBank. A probability threshold for E values ≤ 10−6 was used to assign functions, whereas E values greater than 10−6 were considered not significant. Based on homology to already known or predicted genes and gene products, the 2,102 ESTs were grouped into four main categories: metabolism (33%), cell cycle and plant development (9%), interaction with the environment (26%), and unknown function (32%). The ESTs were further grouped into 16 subcategories (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Based on homology (E values ≤ 10−6), the 2,102 ESTs from proteoid roots of P-deficient white lupin were grouped into four main categories and 16 different subgroups.

Contigs

Redundant ESTs were grouped into contigs using the program Phrap/Consed (University of Washington, Seattle) with a minimum overlap length of 50 bp and a minimum Smith Waterman score of 80. The latter refers to a cumulative score for the alignment that increases for any positive match, whereas it decreases for any mismatch or gap. A total of 322 contigs and 1,126 unique genes compiled to a nearly unigene set of 1,448 different transcripts. The term “nearly” in this context refers to the possibility that two ESTs, though corresponding to the same gene, do not overlap, and in this case would not be grouped into the same contig. We found 35 contigs containing five or more ESTs; the largest (PR-10 protein) consisted of 34 ESTs (Table I). Of the total 322 contigs, 199 contigs (about 60%) contained two ESTs and, together with the singletons, were considered relatively low-copy gene transcripts. Many ESTs that produced identical BLAST hits were grouped into the same contig, but we also found a number of ESTs with similar, but not identical, DNA sequences that may encode different isoforms.

Table I.

Representation of contigs containing five or more ESTs

| Accession No. of GenBank Hit | E Value of Tentative Consensus Sequence | Annotation | Possible Function | Count of ESTs 7 and 10 DAE | Count of ESTs 12 and 14 DAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP_187461.1 | 1E-131 | MATE | Transport | 0 | 10 |

| Q9LTS3 | 8E-24 | Cytokinin oxidase | Cytokinin degradation | 0 | 5 |

| AAF63205.1 | 2E-23 | Transcription factor ERF1 | Regulation | 0 | 5 |

| Q9M4Y9 | 3E-20 | AP2 domain-containing protein | Development | 1 | 4 |

| METE_MESCR | 2E-60 | Met synthase | Ethylene synthesis | 1 | 4 |

| Q9SJQ9 | 4E-47 | Fru-bisphosphate aldolase, cytoplasmic | Glycolysis | 3 | 9 |

| Q9XG67 | 2E-62 | Glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase | Glycolysis | 5 | 10 |

| GTX6_SOYBN | 2E-59 | Glutathione S-transferase | Oxidative stress response | 2 | 5 |

| O65332 | 1E-53 | Polyubiquitin | Protein degradation | 3 | 6 |

| Q9AT55 | 1E-110 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | Ethylene synthesis | 9 | 11 |

| Q43183 | 1E-72 | Sulfate adenyltransferase | Sulfate assimilation | 2 | 3 |

| SAHH_ARATH | 1E-107 | Adenosyl-homocysteinase | Ethylene synthesis | 2 | 3 |

| O81361 | 2E-33 | Ribosomal protein S-8 | Translation | 2 | 3 |

| TBA_PRUDU | 1E-150 | Alpha tubulin | Cell structure | 2 | 3 |

| IDHP_MEDSA | 5E-65 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | Carbon metabolism | 2 | 3 |

| THI4_CITSI | 4E-55 | Thiazole biosynthetic enzyme | Thiamin biosynthesis | 3 | 3 |

| P33560 | 4E-88 | Tonoplast membrane integral protein | Transport | 3 | 3 |

| TBB_CICAR | 3E-41 | Beta tubulin | Cell structure | 3 | 3 |

| Q9LSF3 | 4E-47 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | Protein folding | 3 | 2 |

| Q9AT52 | 8E-17 | Extensin | Cell wall structure | 3 | 2 |

| BAB63949 | 3E-49 | PR-10 protein | Defense | 20 | 14 |

| EF1A_LYCES | 1E-50 | Elongation factor 1-alpha | Translation | 6 | 3 |

| Q9M5M7 | 5E-79 | 60 S Ribosomal protein L-10 | Translation | 5 | 1 |

| Q9LM03 | 1E-105 | Met synthase | Ethylene synthesis | 6 | 3 |

| ALF_CICAR | 1E-65 | Fru-bisphosphate aldolase, cytoplasmic | Glycolysis | 7 | 3 |

| Q9SXL7 | 1E-63 | Ribosomal protein L3 | Translation | 4 | 1 |

| CAA69353.1 | 9E-20 | Tonoplast intrinsic protein | Transport | 4 | 1 |

| P30172 | 1E-115 | Actin | Cell structure | 4 | 1 |

| Q9FNV7 | 3E-24 | Auxin-repressed protein | Development | 5 | 1 |

| O65357 | 9E-62 | Aquaporin2 | Transport | 6 | 1 |

| Q9MAV9 | 5E-48 | Ribosomal protein S-13 | Translation | 5 | 0 |

| O81926 | 6E-70 | Thaumatin | Stress response | 6 | 0 |

| CAC01618.1 | 5E-70 | Aquaporin | Transport | 7 | 0 |

| O49874 | 4E-98 | Aquaporin | Transport | 13 | 4 |

| Q9LKJ6 | 9E-75 | Plasma membrane intrinsic protein | Transport | 14 | 1 |

To identify genes that might be primarily expressed in early or later stages of proteoid root development, we compared the representation of contigs in the two cDNA libraries derived from proteoid roots at early (7 and 10 DAE) and later (12 and 14 DAE) developmental stages (Table I). Contigs that were only represented in the 7- and 10-DAE proteoid root library include a contig containing five ESTs with homology to a ribosomal protein S13, a contig of six ESTs with homology to thaumatin, and a contig with seven ESTs with homology to aquaporin. Contigs that were found only in the 12- and 14-DAE proteoid root cDNA library include a contig of five ESTs with homology to cytokinin oxidase, a contig of five ESTs with homology to a transcription factor ERF-1, and a contig of 10 ESTs with homology to a multidrug and toxin extrusion protein (MATE), a putative transporter. Two contigs with homology to Fru-bis-P aldolase were differentially represented in both cDNA libraries. One isoform represented by 10 ESTs was found seven times in the cDNA library of early proteoid roots and three times in the cDNA collection from 12- and 14-DAE proteoid roots. A second contig of ESTs with homology to Fru bis-P aldolase was found primarily in the cDNA collection from 12- and 14-DAE proteoid roots (nine of 12 copies). The 5′ sequences of both cDNAs share 71% identity over a region of about 700 bp.

Nylon Filter Arrays

To assess global gene expression in proteoid roots, nylon filter arrays of the 2,102 ESTs from P-deficient proteoid roots were performed. The cDNA of each EST was amplified by PCR, using standard T3 and T7 primers, and spotted on nylon membranes. The 1,259 ESTs from later developmental stages of proteoid root development (12 and 14 DAE) were spotted on two sets of filters (Arrays I and II) in replicate (two spots per EST per filter), using a multiple channel pipetter. In addition, all 2,102 ESTs from earlier and later stages of proteoid root development were spotted mechanically in replicate (two spots per EST per filter) on two sets of nylon filters, using an automated Q-bot (Genetix, Boston); these arrays were designated Arrays III and IV. Gene expression was compared in 10-, 12-, and 14-DAE −P proteoid roots, and in +P normal roots, −P normal roots, +P leaves, and −P leaves at 14 DAE. Nylon filter arrays were performed in two to four replicates using RNA from independent plant tests.

To visually estimate the variability of signal intensities from nylon filter arrays, scatter plot analysis proved valuable. Examples for scatter plot analysis are shown in Figure 2. Guide lines at y = 2x and y = x/2 indicate a 2-fold increase or decrease of signal intensities between the compared conditions. Parallel-spotted cDNA from the same hybridization (referred to as positions A and B) showed good correlation, except for those with low signal intensities (Fig. 2A). It should be noted, however, that the comparison of gene expression from different tissues was performed in parallel hybridizations and, thus, might show a lesser degree of correlation. Because of the high internal signal variation at low intensities, ESTs with average signal intensities below 10% of the mean array signal intensities were not analyzed further. Figure 2, B and C, display scatter plots from average intensities of the four independent nylon filter arrays (Arrays I–IV). In Figure 2B, arrays were hybridized with first strand cDNA from12-DAE −P proteoid root, and in Figure 2C arrays were hybridized with first strand cDNA from 14-DAE −P proteoid roots. Both test hybridizations are plotted against the same control hybridization, performed with first strand cDNA from +P normal root. Although Figure 2B shows some differential gene expression in 12-DAE −P proteoid roots, compared with +P normal roots, indicated as spots above and below the guide lines, Figure 2C shows much greater changes of gene expression in 14-DAE −P proteoid roots, compared with +P normal roots.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot analysis of signal variability. For comparison of signal variation, guidelines were added at y = 2x and y = x/2, indicating a 2-fold increase and a 2-fold decrease in signal intensity. A, Average signal intensities of two replicate spots (positions A and B) from the same hybridization (Array I, hybridized with first strand cDNA from −P proteoid roots at 14 DAE). At low intensities, signal variability exceeds a 2-fold increase or decrease. Thus, ESTs with average signal intensities below 10% of the mean array intensities were not included in our EST selections. B and C, Average intensities from four independent nylon filter arrays. In B and C, signal intensities from hybridizations with first strand cDNA derived from −P proteoid roots were plotted against signal intensities from hybridization with first strand cDNA derived from +P normal root. C, Higher signal variation in 14-DAE −P proteoid root, compared with 12-DAE −P proteoid roots (B).

Slopes of approximately 1 in the scatter plots indicate that overall gene expression was quite similar in −P proteoid roots and +P normal roots. In general, expression in roots tended to be higher than in leaves in both −P and +P conditions. Overall expression was lower in −P normal roots compared with +P normal roots and lower in −P leaves compared with +P leaves (data not shown).

To select differentially expressed genes, average intensities from both replicate spots per EST were calculated for each hybridization. Rates for relative expression were calculated for each EST as ratios by dividing the average intensities of the test hybridizations by the average intensities of the control hybridizations. The calculated ratios were compared in all independently replicated arrays. ESTs from the 7- and 10-DAE proteoid root library that displayed at least 2-fold higher intensities in 10 DAE −P proteoid roots compared with +P normal roots (ratio ≥ 2) in both replicate arrays tested are summarized in Table II. ESTs from the 12- and 14-DAE proteoid root library that displayed at least 2-fold higher intensities in −P proteoid roots from 12 or 14 DAE, compared with +P normal roots (ratio ≥ 2), in all four replicate arrays tested are summarized in Table III. Based on these criteria, we found 35 genes that showed enhanced expression in −P proteoid roots at different developmental stages, compared with +P normal roots (Tables II and III). However, we found only one contig (EST nos. 241, 847, 998, 1,032, and 1,036, homology to cytokinin oxidase) that consistently showed reduced expression (ratio ≤ 0.5) in any stage of proteoid root development, compared with +P normal roots. As can be seen in Table III, ESTs with homology to cytokinin oxidase displayed low transcript abundance in 10- and 12-DAE but enhanced expression in 14-DAE −P proteoid roots, compared with +P normal roots.

Table II.

White lupin ESTs derived from a cDNA library of proteoid roots at 7 and 10 DAE were hybridized against first strand cDNA of different tissues

| EST Identification No. | GenBank Accession No. of EST | Accession No. of GenBank Hit | BLASTX E Value | Annotation | Possible Function | Ratio of

Expressiona

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −P Proteoid Root/+P

Normal Root

|

Normal Root

|

Leaf

|

||||||||

| 10 DAE | 12 DAE | 14 DAE | −P/+P | −P/+P | ||||||

| E22, E99, E372 | CA410752, CA526338, CA526349 | AAC16012.1 | 9E-76 | Polyubiquitin | Here, serves as control | 1 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| E170, E292, E304 | CA526339, CA411008, CA411018 | Q9SJQ9 | 4E-47 | Fru-1,6-bisP aldolase | Glycolysis | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| E100, E111, E147, E440, E549, E625, E790 | CA410825, CA410836, CA410872, CA411147, CA411156, CA411327, CA411489 | Q9XG67 | 2E-62 | NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde-3P dehydrogenase | Glycolysis | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| E241 | CA410959 | O42908 | 1E-62 | 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate mutase | Glycolysis | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.7 |

| E18 | CA410748 | CAB75428.1 | 1E-68 | Enolase | Glycolysis | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.5 |

| E171, 447 | CA410895, CA411154 | AAL11502.1 | 5E-63 | Malate dehydrogenase | Glycolysis | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.8 |

| E112, E423, E677 | CA410837, CA411130, CA411379 | AF520576 | 5E-27 | Extensin-like protein | Cell wall structure protein | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| E81, E757, E796 | CA410808, CA411457, CA411495 | BAB33421.1 | 2E-25 | Putative senescence-associated protein | Unknown | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 |

| E183 | CA410907 | NP_198080.1 | 5E-17 | Putative protein | Unknown | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| E711 | CA411412 | No significant match | Unknown | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | ||

Listed are ESTs that displayed induced expression in −P proteoid roots, compared to +P normal roots.

Values represent averages from two independent nylon filter arrays.

Table III.

White lupin ESTs derived from a cDNA library of proteoid roots at 12 and 14 DAE were hybridized against first strand cDNA derived from different tissues

| EST Identification No. | GenBank Accession No. of EST | Accession No. of GenBank Hit | BLASTX E Value | Annotation | Possible Function | Ratio of

Expressiona

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −P Proteoid Root/+P

Normal Root

|

Normal Root

|

Leaf

|

||||||||

| 10 DAEa | 12 DAEb | 14 DAEb | −P/+Pb | −P/+Pb | ||||||

| 518, 587, 787, 820, 1,359 | CA410255, CA410317, CA410522, CA410554, CA409802 | AAC16012.1 | 9E-76 | Polyubiquitin | Here, serves as control | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.4 |

| 769, 823, 1,085, 1,146 | CA410503, CA410557, CA409546, CA409608 | AAK51700.1 | 1E-99 | Secreted purple acid phosphatase | Pi acquisition | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 6.5 | 11.3 ± 15.8 | 3 ± 5.7 | 1.2 ± 1.2 |

| 901 | CA410634 | AAG40473.1 | 2E-68 | Novel acid phosphatase | Pi recycling | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 5 | 12.9 ± 16 | 9.5 ± 13 | 2.1 ± 0.9 |

| 488 | CA410221 | JC4867 | 5E-35 | Ribonuclease | Pi recycling | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 1 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.7 |

| 649, 657 | CA410377, CA410386 | AAK38196.1 | 3E-80 | Phosphate transporter | Pi uptake | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| 131, 449, 471, 584, 685, 729, 1,020, 1,160, 1,281, 1,297 | CA409769, CA410182, CA410204, CA410314, CA410416, CA410461, CA409484, CA409623, CA409730, CA409746 | NP_187461.1 | 1E-131 | MATE | Transport, extrusion | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 2.1 | 8.6 ± 6.7 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.6 |

| 872, 1,421 | CA410603, CA409864 | AAF80647.1 | 7E-39 | Nodulin 21-like protein | Integral membrane protein | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.7 |

| 197, 904 | CA409931, CA410636 | CAC32462.1 | 3E-83 | Sucrose synthase | Glycolysis | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| 245 | CA409981 | G6PD_MEDSA | 8E-33 | Glc-6P dehydrogenase | Glycolysis | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.5 |

| 103, 1,097 | CA840666, CA409559 | T06011 | 1E-140 | PPi dependent phosphofructokinase | Glycolysis | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 3 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| 133, 350, 538, 647, 786, 834, 836, 896, 1,399 | CA409784, CA410092, CA410100, CA410375, CA410521, CA410569, CA410571, CA410627, CA409843 | Q9SJQ9 | 4E-47 | Fru-1,6-bisP aldolase | Glycolysis | 2.1 ± 1 | 4 ± 1.3 | 3.1 ± 2.4 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.4 |

| 1,098, 1,211 | CA409560, CA409671 | TPIS_COPJA | 3E-54 | Triose-P isomerase | Glycolysis | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 1 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.7 |

| 14, 199, 263, 418, 470, 578, 799, 1,141, 1,265, 1,293 | CA409888, CA409932, CA410001, CA410155, CA410203, CA410309, CA410531, CA409604, CA409716, CA409742 | Q9XG67 | 2E-62 | Glyceraldehyde-3P dehydrogenase (NAD) | Glycolysis | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| 33, 415, 490, 1,000 | CA410080, CA410152, CA410224, CA409465 | PGKY_WHEAT | 1E-130 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | Glycolysis | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 1.4 |

| 508 | CA410244 | CAB75428.1 | 1E-68 | Enolase | Glycolysis | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 1 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| 626, 1,394 | CA410354, CA409839 | AAL11502.1 | 5E-63 | Malate dehydrogenase | Glycolysis | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| 1,035, 1,156 | CA409498, CA409618 | CAC28225.1 | 8E-60 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | Glycolysis | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.5 |

| 771, 1,407 | CA410506, CA409851 | P45458 | 8E-66 | Malate synthase | Glyoxysomal pathway | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 4.7 ± 2.7 | 3.9 ± 2.8 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.5 |

| 218, 728 | CA409954, CA410460 | NP_196982.1 | 8E-53 | Formate dehydrogenase | Anaerobic metabolism | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 3.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

| 41, 61, 109, 187 | CA410157, CA410348, CA409562, CA409923 | BAB63595 | 1E-105 | Formamidase-like protein | Function unknown in plants | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 4 ± 3.4 | 7.3 ± 10.6 | 1 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| 241, 847, 998, 1,032, 1,036 | CA409977, CA410582, CA410728, CA409495, CA409499 | CAA77151.1 | 7E-23 | Cytokinin oxidase | Cytokinin degradation | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.7 |

| 865 | CA410597 | AAD38147.1 | 1E-42 | 1-Aminocyclo propane-1 carboxylate oxidase | Ethylene biosynthesis | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.6 |

| 723 | CA410456 | NP_194614.1 | 7E-56 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase | Root hair development | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 1 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.6 |

| 374 | CA410116 | AF139532_1 | 1E-25 | CytochromeP 450 | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 2 ± 1.4 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 1 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.6 |

| 789, 1,112, 1,129 | CA410523, CA409576, CA409592 | T09399 | 4E-59 | Caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyl transferase | Lignin synthesis | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.4 |

| 955 | CA410689 | F19G10.5 | 9E-13 | Similar to CotA (laccase) | Lignin synthesis | 2.4 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.4 |

| 342, 343 | CA410083, CA410084 | T08585 | 3E-53 | Calmodulin | Signal transduction | 1 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 2.9 | 4.9 ± 5 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| 210 | CA409946 | AAF86307.1 | 2E-25 | Ca2+-binding protein | Signal transduction | 1 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| 702 | CA410435 | T49815 | 6E-11 | Cyclin-dependent kinase PHO85-like | Response to Pi starvation | 1.6 ± 0 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 2.3 | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

| 65, 1,059, 1,090 | CA410389, CA409520, CA409552 | T45939 | 3E-35 | Early nodulin ENOD18 | ATP-binding motif | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

| 674 | CA410405 | NP_197145.1 | 6E-32 | Unknown protein | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 3 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | |

| 315 | CA410054 | No match | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 1 | 1 ± 0.6 | |||

Listed are ESTs that displayed induced expression in −P proteoid roots, compared to +P normal roots.

Values represent averages from two independent nylon filter arrays.

Values represent averages from four independent nylon filter arrays.

Confirmation of Expression Pattern for Selected ESTs by RNA Gel Blots

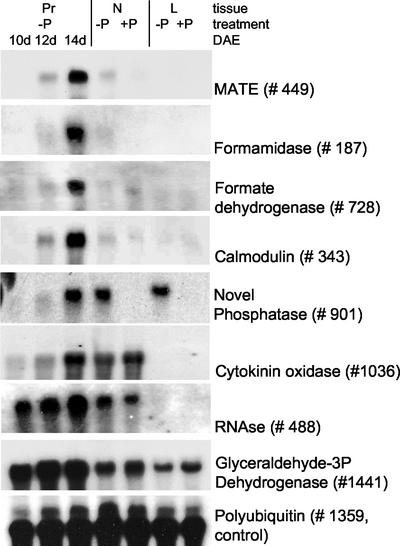

RNA gel blots (Fig. 3) and reverse gel-blot analysis (data not shown), performed with selected ESTs, confirmed the results obtained by nylon filter arrays. As can be seen in Figure 3, the induction patterns obtained with RNA gel blots correlate well with those revealed in nylon filter arrays. ESTs with homology to MATE (EST no. 449), formamidase (EST no. 187), FDH (EST no. 728), and calmodulin (EST no. 343) displayed enhanced expression in −P proteoid roots at 14 DAE. An EST with homology to cytokinin oxidase displayed some induction in −P proteoid roots at 14 DAE but showed reduced expression in −P proteoid roots at 10 and 12 DAE, compared with normal roots. ESTs with homology to a glyceraldehyde-3P dehydrogenase (EST no. 1,141) and an RNase (EST no. 488) displayed significant induction throughout all developmental stages. An EST with homology to a novel phosphatase (no. 901) displayed enhanced expression in 14-DAE −P proteoid roots and −P normal roots compared with +P roots and in −P leaves compared with +P leaves.

Figure 3.

RNA gel analysis of selected ESTs confirmed enhanced expression patterns similar to those determined by nylon filter array analysis. ESTs with homology to MATE (EST no. 449), formamidase (EST no. 187), formate dehydrogenase (FDH; EST no. 728), and calmodulin (EST no. 343) displayed enhanced transcript abundance in 14-DAE −P proteoid roots. EST number 901 with homology to a novel acid phosphatase also showed enhanced expression in −P normal roots and −P leaves. An EST with homology to a cytokinin oxidase (EST no. 1,036) displayed some induction in −P proteoid roots at 14 DAE but showed a decrease of expression in proteoid roots at 10 and 12 DAE, compared with +P and −P normal roots. ESTs with homology to extracellular ribonuclease (RNAse; EST no. 488) and NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase (EST no. 1,441) displayed induction at all stages of proteoid root development, compared with +P or −P normal roots. All RNA gel blots were performed in replicate. Polyubiquitin (EST no. 1,359) served as control for equal loading. Pr, Proteoid root; N, normal root; L, leaf.

Comparison of Gene Induction in P-Deficient Roots of M. truncatula

To determine whether our findings of differentially expressed genes in P-deficient white lupin occurred in another legume species, we searched the M. truncatula Gene Index (MtGI; http://www.tigr.org) to identify genes that were primarily (≥60%) represented in a cDNA library derived from roots of P-starved M. truncatula (MHRP−, Maria Harrison, Noble Foundation, Ardmore, OK), as compared with all other accessible M. truncatula cDNA libraries. The cDNA library MHRP− contains 4,388 ESTs, compiled to 3,936 tentative consensus (TC) sequences and 452 singletons. ESTs that were found in high frequency in the cDNA library MHRP− include two putative acid phosphatases, TC32797 (E value = 1E-150) and TC41065 (E value = 2E-68). TC32797 was found eight times in the −P root cDNA library, compared with only one corresponding EST in the library derived from +P roots, whereas TC41065 was found three of four times in the −P root library. TC32797 displayed about 60% homology to four ESTs encoding secreted acid phosphatase in white lupin (EST nos. 769, 823, 1,085, and 1,146), whereas TC41065 did not show significant homology to any acid phosphatases identified in white lupin. Medicago ESTs that were found exclusively in the MHRP− cDNA library also include two contigs with homology to cytochrome P450 (TC40856, five copies; and TC33723, four copies), both displaying about 40% sequence identity with EST number 374 from white lupin (cytochrome P 450, E value = 1E-25). A putative MATE protein (TC38392, E value = 3E-65) was found in two copies in the MHRP− cDNA library; however, the TC sequence did not display significant sequence identity to the ESTs with homology to a putative MATE protein identified in white lupin (EST nos. 131, 449, 471, 584, 685, 729, 1,020, 1,160, 1,281, and 1,297).

Nylon filter arrays were performed to assess: (a) whether a probe made from RNA isolated from −P-stressed M. truncatula would show hybridization patterns similar to those obtained with RNA from −P proteoid roots of white lupin, and (b) whether similar genes were induced upon −P stress of M. truncatula as those in white lupin. The 1,259 ESTs derived from white lupin proteoid roots at 12 and 14 DAE were hybridized in parallel with first strand cDNA derived from RNA of +P and −P roots of M. truncatula. This hybridization was repeated with cDNA from an independent plant test on nylon filter arrays of 100 selected ESTs.

The majority of genes were either not expressed in M. truncatula or might not share a sufficient degree of homology. Cross hybridization requires sequence identity of at least about 80% sequence identity (Wu et al., 2001). As can be seen in Table IV, a number of white lupin ESTs showed enhanced expression in −P roots of M. truncatula compared with +P roots. A BLASTn search against the M. truncatula Gene Index revealed that these lupin ESTs displayed at least 79% sequence identity with TC sequences of M. truncatula, whereas a lupin EST corresponding to an acid phosphatase and sharing about 60% sequence identity with an M. truncatula TC did not show cross hybridization.

Table IV.

White lupin ESTs that displayed induced expression in M. truncatula −P normal roots, compared with +P normal roots

| EST Identification No. | GenBank Accession No. of EST | Accession No. of GenBank Hit | BLASTX E Value | Annotation | Possible Function | Ratio of Expressiona (−P Normal Root: +P Normal Root) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 183 | CA409919 | CAC32462.1 | 3E-83 | Suc synthase | Glycolysis | 4.9 ± 1.5 |

| 1,211 | CA409671 | TPIS_COPJA | 3E-54 | Triose-P isomerase | Glycolysis | 4.7 ± 1.9 |

| 1,141 | CA409604 | G3PC_MAGLI | 2E-72 | NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde-3Pdehydrogenase | Glycolysis | 3.7 ± 0.5 |

| 508 | CA410244 | CAB75428.1 | 1E-68 | Enolase | Glycolysis | 3.4 ± 1.4 |

| 1,035 | CA409498 | CAC28225.1 | 8E-60 | Phosphoenolpyruvatecarboxylase | Glycolysis | 5.8 ± 2.1 |

| 1,033 | CA409496 | CAA11025.1 | 2E-72 | Aquaporin | Transport | 3.9 ± 1 |

| 20 | CA409945 | AF325121_1 | 6E-44 | Brassinosteroid biosynthetic protein | Root elongation | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| 912 | CA410659 | NP_192570.1 | 1E-60 | Nodulin-like protein | Integral membrane protein | 6.2 ± 0.2 |

Values represent averages of two independent nylon filter arrays.

Five ESTs identified as more highly expressed in roots of −P M. truncatula showed homology to enzymes of the glycolytic pathway: a Suc synthase (EST no. 183), a triose-P isomerase (EST no. 1,211), an NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase (EST no. 1,441), an enolase (EST no. 508), and a phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (EST no. 1035).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have advanced the fundamental understanding of plant adaptation to −P stress by: (a) isolating 2,102 ESTs from proteoid roots of P-deficient white lupin; (b) identifying 35 genes that are more highly expressed under −P in different stages of proteoid root development; (c) demonstrating differential patterns of gene expression under −P in proteoid roots, normal roots, and leaves; and (d) identifying genes potentially more highly expressed in roots of P-deficient M. truncatula by heterologous hybridization against white lupin nylon filter arrays. Our results revealed a suite of responses in proteoid roots of P-deficient white lupin that may be involved in: inorganic phosphate (Pi) acquisition, recycling, and transport; an adapted C metabolism; enhanced secondary metabolism; root development; and signal transduction. Interestingly, although 35 genes showed enhanced expression under P-deficient conditions, some 2,000 genes showed little change in expression in −P proteoid roots versus +P normal roots.

cDNA libraries and Nylon Filter Array Data

A comparison of expression patterns revealed by nylon filter arrays and contig representation in both proteoid root cDNA libraries displayed good correlation. Contigs comprised of five or more ESTs that showed enhanced expression in more mature proteoid roots (14 DAE) compared with juvenile proteoid roots (10 DAE) were more highly represented in the library of more mature proteoid roots (12 and 14 DAE), namely contigs with homology to cytokinin oxidase (EST nos. 241, 847, 998, 1,032, and 1,036), MATE (EST nos. 131, 449, 471, 584, 685, 729, 1,020, 1,160, 1,281, and 1,297), and a Fru-bis-P aldolase isoform (EST nos. E170, E292, E304, 133, 350, 538, 647, 786, 786, 834, 836, 896, and 1,399). However, the majority of contigs that showed higher representation in one of the cDNA libraries did not display enhanced expression in the corresponding tissue in nylon filter arrays. This might be due in part to the relatively strict selection criteria used for the analysis of nylon filter arrays. More sensitive methods like RNA gel blots and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR would be useful to further explore the expression pattern of these contigs. It should also be acknowledged that a comparison of cDNA representation and nylon filter arrays could be complicated by the potential of cross hybridization of closely related sequences (Wu et al., 2001; Fedorova et al., 2002; Miller et al., 2002).

Although we identified 35 genes with enhanced expression in proteoid roots compared with +P normal roots (Tables II and III), we could only identify one contig (EST nos. 241, 847, 998, 1,032, and 1,036, homology to cytokinin oxidase) that displayed less than 0.5-fold expression in all replicate arrays. One reason for the low representation of ESTs that displayed a significant decrease of expression in proteoid roots compared with +P normal roots, might be the fact that both cDNA libraries were derived from proteoid root tissue. Thus, genes with low expression in proteoid roots might be underrepresented in these libraries.

A complete list of the 2,102 ESTs including BLASTX annotations, nylon filter array results, and GenBank accession numbers are accessible on our supplemental Web site (http://home.earthlink. net/∼whitelupinacclimation).

Pi Acquisition and Recycling

Secretion of acid phosphatase from roots of P-deficient plants is a known adaptive mechanism to release organically bound Pi (Duff et al., 1991; Tadano and Sakai, 1991; Gilbert et al., 1999). Previous results from our laboratory revealed induced expression of two acid phosphatase isoforms, a secreted and a membrane-bound form (Gilbert et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2001) in −P proteoid roots. In our selection of 2,102 ESTs, four ESTs (nos. 769, 823, 1,085, and 1,146) correspond to the secreted acid phosphatase and one EST (no. 617) corresponds to the membrane-bound isoform. Consistent with previous results (Miller et al., 2001), the secreted isoform displayed high induction in 14-DAE −P proteoid roots. In addition, we identified an EST (no. 901) with homology to LEPS2, a P starvation-induced novel acid phosphatase from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum; Baldwin et al., 2001). Baldwin et al. (2001) reported rapid induction of LEPS2 under −P in roots, stems, and leaves. Consistent with these findings, nylon filter arrays and RNA gel blots of the corresponding EST number 901 in white lupin revealed enhanced expression under −P in roots (normal and proteoid) and leaves. The enhanced expression in P-deficient leaves suggests involvement of EST number 901 in internal Pi remobilization rather than in Pi acquisition. Due to the low substrate specificity, acid phosphatases are presumed to play a role in the nonspecific hydrolysis of internal Pi to restore the Pi pool. A Pi starvation-inducible extracellular acid phosphatase in aerial tissues of higher plants has been speculated to be involved in scavenging Pi from xylem-derived phosphocholine, a major component of plant xylem sap (Plaxton and Carswell, 1999).

A combination of Pi released by acid phosphatase and enhanced uptake is considered an important means for plants grown under −P to acquire Pi from the rhizosphere (Plaxton and Carswell, 1999; Raghothama, 1999). Previous results from our laboratory (Liu et al., 2001) revealed induced expression of a putative Pi transporter, referred to as LaPT1, in P-deficient proteoid roots of white lupin. Two ESTs (nos. 649 and 657) from our collection proved identical to the LaPT1 gene and displayed enhanced induction in −P proteoid roots.

Induction of intracellular or RNase isozymes has been reported for Pi-starved Arabidopsis, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), and cultured tomato suspension cells (Jost et al., 1991; Loffler et al., 1993; Bariola et al., 1994; Dodds et al., 1996). We identified an EST (no. 741) with homology to an RNase that showed significant induction in −P proteoid roots and, to a lesser degree, in −P normal roots. Enhanced expression of an RNase isoform is consistent with the report of a drastic decrease of RNA concentration in mature proteoid roots of white lupin (Johnson et al., 1994; Neumann et al., 2000).

Organic Acid Synthesis

The excretion of malate and citrate from proteoid roots of white lupin in response to −P has been well documented (Dinkelaker et al., 1989; Johnson et al., 1996a; Neumann et al., 2000). Excretion of organic acids from roots has also been implicated as an adaptation to Al tolerance (Jones, 1998; Ryan et al., 2001). Organic acids allow for the displacement of Pi from Al3+-, Fe3+-, and Ca2+-phosphates (Dinkelaker et al., 1989; Gerke et al., 1994), thus freeing bound Pi. In addition, plant uptake of Pi hydrolyzed by acid phosphatase is thought to be improved by the presence of citrate, a chelate that binds metals otherwise competing for released Pi (Braum and Helmke, 1995). We have shown previously that genes of most enzymes of the glycolytic pathway are represented in our EST collection from 12- and 14-DAE proteoid roots. These ESTs display significant induction in −P proteoid roots, indicating the involvement of this pathway in organic acid synthesis in proteoid roots (Uhde-Stone et al., 2003). In addition, enhanced expression of two ESTs with homology to a glyoxysomal malate synthase (nos. 771 and 1,407) support the involvement of this enzyme in the synthesis of organic acids. The 2,102 ESTs presented here include ESTs with homologies to all enzymes of the glycolytic pathway except an ATP-dependent phosphofructokinase and a pyruvate kinase. Interestingly, these two enzymes are thought to be bypassed under −P (Duff et al., 1989; Plaxton and Carswell, 1999). The induction of glycolytic bypass enzymes that do not need ATP or ADP + Pi are thought to facilitate intracellular Pi scavenging (Theodorou et al., 1992; Theodorou and Plaxton, 1996; Plaxton and Carswell, 1999). ESTs with homology to an inorganic pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructokinase, a phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, and a malate dehydrogenase, enzymes that catalyze the supposed bypass reactions, were represented in our EST collection and displayed enhanced expression in −P proteoid roots compared with +P normal roots. We did not, however, find evidence for the expression of an NADP-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase, an enzyme that is thought to catalyze another glycolytic bypass reaction. Although we found no EST with homology to the NADP-dependent form of this enzyme, we did identify 15 highly expressed redundant ESTs corresponding to the regular (non-bypass) NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase. These data indicate that the NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase is not bypassed by an NADP-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase in proteoid roots of P-deficient white lupin. This finding is consistent with that of Penaloza et al. (2002), who reported enhanced expression of a gene with homology to an NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase in P-deficient, compared with P-sufficient, proteoid roots. Although we identified only one isoform of glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase, we found two isoforms of a Fru bis-P aldolase, both forms sharing about 70% sequence identity in the sequenced 5′ coding region. One isoform was primarily represented in the cDNA collection from early proteoid roots (EST nos. E57, E242, E295, E379, E433, E640, E736, 152, 155, and 750), whereas the other isoform was more abundant in the cDNA collection from 12- to 14-DAE proteoid roots (EST nos. E170, E292, E304, 133, 350, 538, 647, 786, 834, 836, 896, and 1,399). Only the latter isoform showed enhanced expression of the corresponding ESTs in −P proteoid roots compared with +P normal roots, indicating that a different isoform of this enzyme might be involved in the increased glycolysis that seems to occur in proteoid roots.

Organic Acid Transport and Proton Excretion

Because malate and citrate are fully dissociated in the cytosol and cell membranes are impermeable to ions, excretion of organic acids from roots probably involves some type of channel protein (Neumann et al., 2000; Ryan et al., 2001). Studies using anion channel antagonists have indicated a possible involvement of anion channel proteins in citrate exudation of proteoid roots (Neumann et al., 2000). Genes encoding a corresponding channel or other protein that facilitates organic acid excretion have not yet been isolated.

An interesting candidate for a putative organic acid transporter is a gene represented by 10 ESTs in our collection of mature proteoid roots (EST nos. 131, 449, 471, 584, 685, 729, 1,020, 1,160, 1,281, and 1,297) that was not present in the EST collection obtained from juvenile stages. The consensus sequence of this contig displayed homology to a putative MATE protein from Arabidopsis. MATE proteins are a large family of putative transporters and are thought to be involved in excretion of a variety of drugs and toxins (Debeaujon et al., 2001; Diener et al., 2001). Nylon filter arrays and RNA gel-blot analysis revealed some induction in P-deficient normal and 12-DAE proteoid roots, but much higher induction in more mature −P proteoid roots at 14 DAE. This timing of induction is consistent with malate and citrate excretion from proteoid roots. Initial findings indicate that the putative MATE gene identified here is also responsive to high Al (+Al) stress (C. Uhde-Stone, C.P. Vance, and D.L. Allan, unpublished data), a condition known to result in organic acid excretion in many plants (Ma et al., 2001). So far, only a few MATE proteins have been analyzed in plants, among them a putative Fe sensor (Rogers et al., 2000; Rogers and Guerinot, 2002) and a protein required for flavonoid sequestration in vacuoles (Debeaujon et al., 2001).

Metabolic Adaptations of Respiration

A gene encoding a putative FDH (EST nos. 218 and 728) displayed high induction in proteoid roots collected at 14 DAE from P-deficient white lupin. FDH catalyzes the oxidation of formate to CO2 in the presence of NAD+. In bacteria and unicellular algae, formate is produced in large quantities under anaerobic conditions by the action of pyruvate formate lyase (Kreuzberg, 1984; Ferry, 1990). It is noteworthy that a pyruvate formate lyase-encoding gene showed significantly enhanced expression under Pi starvation in Chlamydomonas reinhardii (Dumont et al., 1993). Higher plant mitochondria from non-photosynthetic plant tissue can also display high FDH expression (Colas des Francs-Small et al., 1993). Correspondingly, the putative FDH gene from proteoid roots of white lupin contains a likely (P = 0.998) mitochondrial-targeting sequence (Claros and Vincens, 1996). FDH has been previously reported to show induced expression under Fe deficiency in roots of tomato (Herbik et al., 1996) and barley (Hordeum vulgare; Suzuki et al., 1998), probably as a consequence of oxygen deficiency in Fe-deficient tissue. Suzuki et al. (1998) speculated that an impairment of Fe-containing enzymes in oxidative respiration causes an increase in anaerobic metabolism under Fe limitation. Similarly, induction of FDH in −P proteoid roots of white lupin could result from the reduced mitochondrial respiration that has been reported in −P proteoid roots (Johnson et al., 1994; Neumann et al., 1999).

Secondary Metabolism

The accumulation of aromatic secondary metabolites appears to be a common response of plant cells undergoing Pi deprivation (for review, see Plaxton and Carswell, 1999). Plaxton and Carswell (1999) noted that the initial sequence of reactions in the aromatic pathway may serve to recycle Pi from phosphate esters. Enhanced expression of several key enzymes of the aromatic pathway, including 3-deoxy-d-arabinoheptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase, Phe ammonia lyase, and chalcone synthase, has been previously reported in Pi-deficient plant cells (for review, see Plaxton and Carswell, 1999). In addition, isoflavonoids have been shown to be excreted from proteoid roots of white lupin (Neumann et al., 2000).

Table III shows that a number of genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway, the pathway that ultimately leads to products like flavonoids and lignin, were more highly expressed in −P proteoid roots of white lupin. These ESTs encode a cytochrome P 450 (EST no. 374), a caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase (EST nos. 789, 1,112, and 1,129), and a putative laccase (EST no. 955). Some cytochrome P 450s are postulated to be involved in flavone, flavonoid, and anthocyanin synthesis (Kitada et al., 2001). Caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase and laccase encode later steps in phenylpropanoid metabolism and are both implicated in lignin synthesis, a finding that is consistent with the striking proliferation of root growth that occurs during proteoid root development.

Plant Hormones and Proteoid Root Development

The plant hormone auxin has been implicated in the regulation of many aspects of plant growth including proteoid root development (Gilbert et al., 2000). The role of cytokinin, however, is less clear. Although auxins are known to promote lateral root primordia, cytokinins have been reported to have an antagonistic effect on proteoid root development (Neumann et al., 2000). ESTs with homology to cytokinin oxidase (EST nos. 241, 847, 998, 1,032, and 1,036), an enzyme that catalyzes the irreversible degradation of cytokinin (Rinaldi and Comandini, 1999), were induced in 14-DAE proteoid roots but showed reduced expression in 10- and 12-DAE −P proteoid roots compared with +P normal roots. Moreover, ESTs with homology to cytokinin oxidase were found redundantly in the EST collection from 12- and 14-DAE proteoid roots but not in that from 7- and 10-DAE −P proteoid roots. Modified expression of cytokinin oxidase at different stages of proteoid root development may be important in mediating proteoid root induction and/or maturity.

Proteoid root development is known to be accompanied by extensive root hair growth, resulting in a more than 100-fold increased surface area (Dinkelaker et al., 1995; Skene, 2001). The plant hormone ethylene has been proposed to regulate the induction of root hairs (Cao et al., 1999). The production of ethylene in plants is thought to be at least in part controlled by 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) synthase and ACC oxidase in a gene-dependent manner (Chae et al., 2000). The enhanced expression of a predicted ACC oxidase gene (EST no. 865) in −P proteoid roots is consistent with earlier findings that show an enhanced ethylene formation by −P proteoid roots (Gilbert et al., 2000). It should be noted, however, that the application of ethylene inhibitors had no noticeable effect on proteoid root numbers (Gilbert et al., 2000).

Signal Transduction and Regulation

−P is one of many possible abiotic stresses plants might face in the environment. Plants have developed mechanisms to recognize and respond to a variety of stresses. Frequently, this response involves intracellular Ca2+, a second messenger in signal transduction of eukaryotes (for review, see Knight, 2000). Stress- or plant hormone-induced changes in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration can be transduced via calmodulin, Ca-dependent protein kinases, and other Ca2+-controlled proteins. The enhanced expression of ESTs with homology to calmodulin (EST nos. 342 and 343) and Ca2+-binding protein (EST no. 210) in −P proteoid roots suggests the involvement of Ca2+-regulated processes in the response of white lupin to −P. The transduction of an abiotic stress signal, like −P, via calmodulin can affect a wide array of downstream growth and development responses.

Genes Induced in Roots of P-Deficient M. truncatula

To compare our findings of differential gene expression under −P in white lupin with the legume model organism M. truncatula, we searched the MtGI (http://www.tigr.org). The MtGI allows the in silico identification of ESTs that are more highly represented (≥60%) in a cDNA library of roots from P-deficient M. truncatula compared with other cDNA libraries accessible via MtGI. ESTs that were more highly represented in the P-deficient M. truncatula library included TCs with homology to acid phosphatases and cytochrome P450.

Proteoid roots do not form in M. truncatula in response to −P; rather, this species is mycorrhizal (Harrison, 1998). As a consequence, analysis of gene expression in P-deficient M. truncatula has been performed mainly on plants grown in mycorrhizal association. In the nylon filter arrays we performed, we sought to identify genes that show enhanced expression in roots of P-deficient M. truncatula that were grown without mycorrhizal inoculation. As might be expected, the majority of genes did not hybridize strongly with cDNA clones derived from white lupin. Heterologous hybridization of nylon filter arrays does not allow us to distinguish between low expression and low (less than 80%) sequence similarity of M. truncatula genes. It is, however, possible to compare the level of expression in +P and −P roots of M. truncatula for those genes that show sufficient hybridization. Similar to white lupin, M. truncatula displayed significantly induced expression of genes involved in the glycolytic pathway (Table IV). When grown under P-deficient conditions, M. truncatula responds by increasing its root-shoot ratio, a well-documented response to −P in many plants (Lynch and Brown, 1998). In this context, it is of interest that a gene with homology to a brassinosteroid biosynthetic protein (EST no. 20), a homolog to the cell elongation protein diminuto, was found to be induced in P-deficient roots of M. truncatula. This gene was represented by a white lupin EST (EST no. 20) but did not display significantly enhanced expression in −P proteoid roots. Brassinosteroid biosynthetic protein is thought to control the biosynthesis of campesterol, a compound implicated in growth modulation (Schaeffer et al., 2001).

CONCLUSION

Higher plants vary greatly in their ability to obtain and utilize scarcely available Pi. Taken together, the results presented here indicate that the effective adaptation of proteoid roots from white lupin to −P is a result of a complex coordinated regulation of gene expression that influences Pi acquisition and remobilization, carbon and secondary metabolism, and developmental processes. Enhanced expression of glycolysis-related genes in both proteoid roots of P-deficient white lupin and roots of P-deficient M. truncatula indicate some parallels in the response of both plant species to −P. Functional studies in alfalfa (Medicago sativa), M. truncatula, yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and Xenopus sp. oocytes are necessary to identify the proposed functions of proteins encoded by genes. Isolation of genomic clones and identification of promoter elements of P-responsive genes will certainly further our understanding of coordinated gene expression in response to −P.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

White lupin (Lupinus albus L. var Ultra) and Medicago truncatula plants were grown in the growth chamber in sand culture under growth conditions as previously described (Johnson et al., 1996a). P sufficiency or −P was defined by the presence or absence of 0.5 mm Ca(H2PO4)2 in the nutrient solutions, which were replenished every 2 d (Gilbert et al., 2000). To maintain equivalent Ca2+ concentrations, the nutrient solutions for the −P plants contained 0.5 mm CaSO4.

RNA Isolation

For isolation of total RNA, plant tissue was harvested in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. About 5 g of root tissue or 1 g of leaf tissue, respectively, was ground under liquid nitrogen with mortar and pestle and added to 10 mL of cold extraction buffer (0.2 m Na acetate and 10 mm EDTA [pH 5]) and 10 mL of cold phenol. Samples were ground further in a Polytron at half speed for 30 s, than mixed by inversion for 10 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000g. The supernatant was added to 5 mL of phenol and 5 mL of chloroform:isoamylalcohol (24:1 [v/v]), mixed by inversion for 10 min, and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000g. This step was repeated using 10 mL of chloroform:isoamylalcohol (24:1 [v/v]) for extraction. One-third of the supernatant's volume of 8 m LiCl was added for a final concentration of 2 m LiCl and precipitated overnight at 4°C. The RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000g for 15 min. The pellet was washed first with 3 mL of 2 m LiCl and than washed twice with 70% (w/v) ethanol. The pellet was dried and resuspended in about 100 μL of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, dissolved for 30 min at 65°C, and stored at −80°C.

Preparation and Screening of a cDNA Library

Proteoid roots of white lupin grown under P-deficient conditions were harvested 7 10, 12, and 14 DAE, and total RNA was isolated. Poly(A+) RNA was obtained from total RNA using oligo(dT) cellulose. The poly(A+) RNA obtained from early developmental stages (7 and 10 DAE) and those from later developmental stages (12 and 14 DAE) were combined into two pools, each in a 1:1 (w/v) ratio. From each pool, 7 μg of RNA was used for construction of two proteoid root cDNA libraries in the phage Uni-ZAP XR vector according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The linkage of two restriction site adapters, EcoRI and XhoI, allowed 5′- and 3′-directional cloning of the cDNA product into the Uni-ZAP XR vector. The cDNA from both libraries were size selected via Sephacryl S-500 spin columns as part of the procedure described by Stratagene.

Generation of ESTs

For conversion of the two cDNA phage libraries (ZAP XR vector) into the plasmid form (pBluescript), mass excision was performed according to the procedure described by Stratagene. Single colonies of Escherichia coli strain SOLR carrying the excised phagemid were replicated, and glycerol stocks were stored in microtiter plates at −80°C. DNA was isolated using the QIAprep 96 Turbo Miniprep Kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen USA, Valencia, CA). A portion of the obtained DNA was used for 5′ single-stranded sequencing at the Advanced Genetic Analysis Center (St. Paul, MN) using standard T3 sequencing primer. The obtained 5′ single-strand sequences were edited and compared with the nonredundant database at the National Center for Biotechnology using the BLASTX program.

Nylon Filter Arrays

The cDNA portion of each clone was amplified by PCR, using standard T3 and T7 primers. Before spotting, the quality of each PCR product was evaluated by gel electrophoresis. For manual spotting, 0.5 μL (about 0.2 μg) of the amplified cDNA was spotted in parallel onto Gene Screen Plus membranes (NEN Life Science Products, Boston) using an eight-channel pipetter. For automated spotting with the Q-bot (Genetix), a 96-pin gravity gridding head with 0.4-mm pin diameter was used to spot the PCR products (about 0.4 μg DNA μL−1) in replicate on Gene Screen Plus membranes that had been soaked in 6× SSC. A 4 × 4 gridding pattern with an equal spot distance of 2,250 μm was used.

After spotting, nylon filters were positioned face up for 10 min onto Whatman paper (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) soaked with denaturing solution (1.5 m NaCL and 0.5 m NaOH), followed by 5 min of neutralization solution (1.5 m NaCl and 1 m Trizma Base), than dried and exposed at 120 joules cm−2 under a UV cross linker.

Total RNA was isolated from −P proteoid roots at different stages of development (10, 12, and 14 DAE), and from +P and −P normal roots and +P and −P leaves at 14 DAE. For hybridization, 32P-labeled first strand cDNA probe was synthesized by RT of 30 μg of total RNA using SuperScriptII reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). The reaction mixture included 30 μg of total RNA, and 0.5 μg of oligo(dT)12-18 primer (5 units μL−1) that was annealed by heating to 70°C for 10 min in a total volume of 7 μL. Added to the mixture were 4 μL of 5× first strand buffer, 2 μL of 0.1 m dithiothreitol, 1 μL of dNTP mix (2.5 mm each of dCTP, dGTP, dTTP, and 0.0625 mm dATP), 5 μL of [α-32P]dATP (10 mCi mL−1), and 1 μL (200 units) of Superscript II reverse transcriptase. After 1 h of labeling at 42°C, 1 μL of 5 mm ATP was added, and the incubation was allowed to proceed for an additional 30 min. Unincorporated [32P] dATP was removed by passing the mixture through Sephadex G50-G150 columns. 32P incorporation was quantified via liquid scintillation. The final concentration of each probe was adjusted to 106cpm mL−1 hybridization solution.

Hybridizations were performed in 50% (w/v) formamide, 0.5 m Na2HPO4, 0.25 m NaCl, 7% (w/v) SDS, and 1 mm EDTA at 42°C. Blots were washed with three subsequent washes (1× SSC, 0.1% [w/v] SDS; 0.5× SSC, 0.1% [w/v] SDS; and 0.1× SSC, 0.1% [w/v] SDS) at 42°C.

Data Analysis of Nylon Filter Arrays

Radioactivity of each spot was quantified using a Phosphor Screen imaging system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). For manual spotted filters, the signal intensity for each spot of the parallel hybridizations was quantified using the software ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics). For automated spotted arrays, the signal intensity of each spot was determined automatically using the software Array-Pro Analyzer (Media Cybernetics, Carlsbad, CA). Both programs allow the normalization of quantified signals against the background. The normalized intensities were reported as an Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) file sheet and linked to the corresponding cDNA clones.

To identify cDNA clones that were differentially expressed under −P, the intensities from the various test hybridizations (−P proteoid root at different stages of development, −P normal root, and −P leaf) were divided by the intensities from the control hybridization (+P normal root and +P leaf). Ratios of greater than or equal to 2 in all replicates were considered an indication of a significant change of expression. ESTs with homology to polyubiquitin (nos. 518, 587, 787, 820, and 1,359) served as controls for uniform expression among the parallel hybridizations. Original signal intensities and transformed data for all experiments are available from our Web site (http://home.earthlink.net/∼whitelupinacclimation).

RNA Gel Blots

Total RNA from different tissues (15 μg) was separated electrophoretically on 1.5% (w/v) denaturing agarose gels and transferred to Zeta-Probe Blotting Membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) following standard capillary blotting procedures (Sambrook et al., 1989). Blots were hybridized to 32P-labeled cDNA of selected ESTs and probes were prepared by random primer labeling. The RNA was isolated from 10-, 12-, and 14-DAE −P proteoid roots and from +P and −P normal roots and +P and −P leaves at 14 DAE. Hybridizations were performed in 0.5 m Na2HPO4, 7% (w/v) SDS, and 10 mm EDTA at 65°C. Blots were washed with three subsequent washes (2× SSC, 0.5% [w/v] SDS; 1× SSC, 0.5% [w/v] SDS; and 0.5× SSC, 0.5% [w/v] SDS) at 65°C before autoradiography. Equivalent loading of each lane was assessed by probing blots with lupin polyubiquitin DNA. Loading variability was no greater than 20%.

Reverse RNA Gel Blots

About 0.4 μg (1 μL) of PCR-amplified cDNAs was loaded in parallel on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel in Tris-Acetate-EDTA, containing four parallel rows of loading wells. After electrophoresis, the gel was transferred to Immobilon membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) following standard capillary blotting procedures (Sambrook et al., 1989). 32P-labeled first strand cDNA probe was synthesized by RT of 30 μg of total RNA using SuperScriptII reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). The RNA was isolated from mature (14 DAE) −P proteoid roots and +P normal roots. Equal activities of the probes (1 million cpm mL−1) were used for hybridization. Hybridizations were performed in 50% (w/v) formamide, 0.125 m Na2HPO4, 0.25 m NaCl, 7% (w/v) SDS, and 1 mm EDTA at 42°C. Blots were washed with three subsequent washes (2× SSC, 0.1% [w/v] SDS; 0.5× SSC, 0.1% [w/v] SDS; and 0.1× SSC, 0.1% [w/v] SDS) at 42°C. Radioactivity of each band was quantified using the Phosphor Screen imaging system described above.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Ernest Retzel and staff, especially Rod Staggs, Bob Milius, and Tina Schmidt, from the Center for Computational Genomics and Bioinformatics (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis) for support with the computational analysis. We also gratefully acknowledge Kate VandenBosch and Ariana Lindemann (Department of Plant Biology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul) for providing the facility for automated spotting (Q-bot) and for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National-Research Initiative (Competitive Grant nos. USDA–CSREES/98–35100–6098 and USDA–CSREES/2002–35100–12206).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.102.016881.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aono T, Kanada N, Ijima A, Oyaizu H. The response of the phosphate uptake system and the organic acid exudation system to phosphate starvation in Sesbania rostrata. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:1253–1264. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JC, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG. Leps2, a phosphorus starvation-induced novel acid phosphatase from tomato. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:728–737. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariola PA, Howard CJ, Taylor CB, Verburg MT, Jaglan VD, Green PJ. The Arabidopsis ribonuclease gene RNS1 is tightly controlled in response to phosphate limitation. Plant J. 1994;6:673–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6050673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieleski RL. Phosphate pools, phosphate transport, and phosphate availability. Ann Rev Plant Physiol. 1973;24:225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Braum S, Helmke PA. White lupin utilizes soil phosphorus that is unavailable to soybean. Plant Soil. 1995;176:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cao XF, Linstead P, Berger F, Kieber J, Dolan L. Differential ethylene sensitivity of epidermal cells is involved in the establishment of cell pattern in the Arabidopsis root. Physiol Plant. 1999;106:311–317. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1999.106308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae HS, Cho YG, Park MY, Lee MC, Eun MY, Kang BG, Kim WT. Hormonal cross-talk between auxin and ethylene differentially regulates the expression of two members of the 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase gene family in rice (Oryza sativaL.) Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:354–362. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton WA. Patterns and distribution of lateral root primordia. Ann Bot. 1983;51:417–427. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou TJ, Liu H, Harrison MJ. The spatial expression patterns of a phosphate transporter (MtPT1) from Medicago truncatulaindicate a role in phosphate transport at the root/soil interface. Plant J. 2001;25:281–293. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claros MG, Vincens P. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:779–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas des Francs-Small C, Ambard-Bretteville F, Small ID, Remy R. Identification of a major soluble protein in mitochondria from nonphotosynthetic tissues as NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:1171–1177. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.4.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeaujon I, Peeters AJ, Leon-Kloosterziel KM, Koornneef M. The TRANSPARENT TESTA12 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a multidrug secondary transporter-like protein required for flavonoid sequestration in vacuoles of the seed coat endothelium. Plant Cell. 2001;13:853–871. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo JC, Allona I, Rubio V, Leyva A, de la Pena A, Aragoncillo C, Paz-Ares J. A type 5 acid phosphatase gene from Arabidopsis thalianais induced by phosphate starvation and by some other types of phosphate mobilising/oxidative stress conditions. Plant J. 1999;19:579–589. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener AC, Gaxiola RA, Fink GR. Arabidopsis ALF5, a multidrug efflux transporter gene family member, confers resistance to toxins. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1625–1638. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkelaker B, Hengeler C, Marschner H. Distribution and function of proteoid roots and other root clusters. Bot Acta. 1995;108:169–276. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkelaker B, Romheld V, Marschner H. Citric acid excretion and precipitation of calcium citrate in the rhizosphere of white lupin (Lupinus albusL.) Plant Cell Environ. 1989;12:285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds PN, Clarke AE, Newbigin E. Molecular characterisation of an S-like RNase of Nicotiana alatathat is induced by phosphate starvation. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:227–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00021786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff SM, Plaxton WC, Lefebvre DD. Phosphate-starvation response in plant cells: de novo synthesis and degradation of acid phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9538–9542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff SMG, Moorhead GBG, Lefebvre DD, Plaxton WC. Phosphate starvation inducible “bypasses” of adenylate and phosphate dependent glycolytic enzymes in Brassica nigrasuspension cells. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:1275–1278. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont F, Joris B, Gumusboga A, Bruyninx M, Loppes R. Isolation and characterization of cDNA sequences controlled by inorganic phosphate in Chlamydomonas reinhardii. Plant Sci. 1993;89:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dunaeva M, Adamska I. Identification of genes expressed in response to light stress in leaves of Arabidopsis thalianausing RNA differential display. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5521–5529. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova M, Van De Mortel J, Matsumoto PA, Cho J, Town CD, VandenBosch KA, Gantt JS, Vance CP. Genome-wide identification of nodule-specific transcripts in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:519–537. doi: 10.1104/pp.006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JG. Formate dehydrogenase. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;7:377–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner WK, Barber DA, Parbery DG. The acquisition of phosphorus by Lupinus albusL.: III. The probable mechanism by which phosphorus movement in the soil/root interface is enhanced. Plant Soil. 1983;70:107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner WK, Parbery DG, Barber DA. The acquisition of phosphorus by Lupinus albusL.: I. Some characteristics of the soil/root interface. Plant Soil. 1982;68:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gerke J, Roemer W, Jungk A. The excretion of citric and malic acid by proteoid roots of Lupinus albusL.: effect on soil solution concentrations of phosphate, iron, and aluminum in the proteoid rhizosphere in samples of an oxisol and a lurizol. Z Pflanzenernaehr Bodenkd. 1994;157:289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert GA, Knight JD, Vance CP, Allan DL. Acid phosphatase activity in phosphorus-deficient white lupin roots. Plant Cell Environ. 1999;22:801–810. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert GA, Knight JD, Vance CP, Allan DL. Proteoid root development of phosphorus deficient lupin is mimicked by auxin and phosphonate. Ann Bot. 2000;85:921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy S, Jones DL. Through form to function: root hair development and nutrient uptake. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:56–60. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01551-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girke T, Todd J, Ruuska S, White J, Benning C, Ohlrogge J. Microarray analysis of developing Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1570–1581. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorgyey J, Vaubert D, Jimenez-Zurdo JI, Charon C, Troussard L, Kondorosi A, Kondorosi E. Analysis of Medicago truncatulanodule expressed sequence tags. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:62–71. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ. Development of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:360–365. doi: 10.1016/1369-5266(88)80060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbik A, Giritch A, Horstmann C, Becker R, Balzer HJ, Baumlein H, Stephan UW. Iron and copper nutrition-dependent changes in protein expression in a tomato wild type and the nicotianamine-free mutant chloronerva. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:533–540. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JF, Allan DL, Vance CP. Phosphorus stress-induced proteoid roots show altered metabolism in Lupinus albus. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:657–665. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JF, Allan DL, Vance CP, Weiblen G. Root carbon dioxide fixation by phosphorus-deficient Lupinus albus: contribution to organic acid exudation by proteoid roots. Plant Physiol. 1996a;112:19–30. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JF, Vance CP, Allan DL. Phosphorus deficiency in Lupinus albus. Altered lateral root development and enhanced expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase. Plant Physiol. 1996b;112:31–41. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL. Organic acids in the rhizosphere: a critical review. Plant Soil. 1998;205:25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jost W, Bak H, Glund K, Terpstra P, Beintema JJ. Amino acid sequence of an extracellular, phosphate-starvation-induced ribonuclease from cultured tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) cells. Eur J Biochem. 1991;198:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki S, Borchert C, Deyholos M, Wang H, Brazille S, Kawai K, Galbraith D, Bohnert HJ. Gene expression profiles during the initial phase of salt stress in rice. Plant Cell. 2001;13:889–905. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada C, Gong Z, Tanaka Y, Yamazaki M, Saito K. Differential expression of two cytochrome P450s involved in the biosynthesis of flavones and anthocyanins in chemo-varietal forms of Perilla frutescens. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:1338–1344. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight H. Calcium signaling during abiotic stress in plants. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;195:269–324. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzberg K. Starch fermentation via formate producing pathway in Chlamydomonas reinhardii, Chlorogonium elongatum, and Chlorella fusca. Physiol Plant. 1984;61:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Leggewie G, Willmitzer L, Riesmeier JW. Two cDNAs from potato are able to complement a phosphate uptake-deficient yeast mutant: identification of phosphate transporters from higher plants. Plant Cell. 1997;9:381–392. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Muchhal US, Uthappa M, Kononowicz AK, Raghothama KG. Tomato phosphate transporter genes are differentially regulated in plant tissues by phosphorus. Plant Physiol. 1998a;116:91–99. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Trieu AT, Blaylock LA, Harrison MJ. Cloning and characterization of two phosphate transporters from Medicago truncatularoots: regulation in response to phosphate and to colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998b;11:14–22. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Uhde-Stone C, Li A, Vance CP, Allan DL. A phosphate transporter with enhanced expression in proteoid roots of white lupin (Lupinus albusL.) Plant Soil. 2001;237:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Loffler A, Glund K, Irie M. Amino acid sequence of an intracellular, phosphate-starvation-induced ribonuclease from cultured tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) cells. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:627–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP, Brown KM. Lynch JP, Deikman J, eds. Phosphorus in Plant Biology: Regulatory Roles in Molecular, Cellular, Organismic, and Ecosystem Processes. Rockville, MD: American Society of Plant Physiology; 1998. Regulation of root architecture by phosphorus availability; pp. 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Ryan PR, Delhaize E. Aluminum tolerance in plants and the complexing role of organic acids. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants. Ed 2. San Diego: Academic Press Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H, Dell B. Nutrient uptake in mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Soil. 1994;159:89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H, Romheld V, Cakmak I. Root-induced changes of nutrient availability in the rhizosphere. J Plant Nutr. 1987;10:1175–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner HV, Romheld V, Horst WJ, Martin P. Root-induced changes in the rhizosphere: importance for the mineral nutrition of plants. Z Pflanzenernaehr Bodenkd. 1986;149:441–456. [Google Scholar]

- Massonneau A, Langlade N, Leon S, Smutny J, Vogt E, Neumann G, Martinoia E. Metabolic changes associated with cluster root development in white lupin (Lupinus albusL.): relationship between organic acid excretion, sucrose metabolism and energy status. Planta. 2001;213:534–542. doi: 10.1007/s004250100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NA, Gong Q, Bryan R, Ruvolo M, Turner LA, LaBrie ST. Cross-hybridization of closely related genes on high-density macroarrays. Biotechniques. 2002;32:620–625. doi: 10.2144/02323pf01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SS, Liu J, Allan DL, Menzhuber CJ, Fedorova M, Vance CP. Molecular control of acid phosphatase secretion into the rhizosphere of proteoid roots from phosphorus-stressed white lupin. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:594–606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Massonneau A, Langlade N, Dinkelaker B, Hengeler C, Romheld V, Martioia E. Physiological aspects of cluster root function and development in phosphorus-deficient white lupin (Lupinus albusL.) Ann Bot. 2000;85:909–919. [Google Scholar]