Abstract

Although Petunia axillaris subsp. axillaris is described as a self-incompatible taxon, some of the natural populations we have identified in Uruguay are composed of both self-incompatible and self-compatible plants. Here, we studied the self-incompatibility (SI) behavior of 50 plants derived from such a mixed population, designated U83, and examined the cause of the breakdown of SI. Thirteen plants were found to be self-incompatible, and the other 37 were found to be self-compatible. A total of 14 S-haplotypes were represented in these 50 plants, including two that we had previously identified from another mixed population, designated U1. All the 37 self-compatible plants carried either an SC1- or an SC2-haplotype. SC1SC1 and SC2SC2 homozygotes were generated by self-pollination of two of the self-compatible plants, and they were reciprocally crossed with 40 self-incompatible S-homozygotes (S1S1 through S40S40) generated from plants identified from three mixed populations, including U83. The SC1SC1 homozygote was reciprocally compatible with all the genotypes examined. The SC2SC2 homozygote accepted pollen from all but the S17S17 homozygote (identified from the U1 population), but the S17S17 homozygote accepted pollen from the SC2SC2 homozygote. cDNAs encoding SC2- and S17-RNases were cloned and sequenced, and their nucleotide sequences were completely identical. Analysis of bud-selfed progeny of heterozygotes carrying SC1 or SC2 showed that the SI behavior of SC1 and SC2 was identical to that of SC1 and SC2 homozygotes, respectively. All these results taken together suggested that the SC2-haplotype was a mutant form of the S17-haplotype, with the defect lying in the pollen function. The possible nature of the mutation is discussed.

Naturally occurring or induced (e.g. by radiation) self-compatible mutants of self-incompatible species in the Solanaceae have provided useful materials for studying the mechanism of the S-RNase-mediated self-incompatibility (SI) system. For example, molecular genetic studies of a self-compatible line of Lycopersicon peruvianum have suggested that the RNase activity of S-RNases is an integral part of the SI mechanism because mutations in the S-RNase gene rendering its protein product without the RNase activity cause the breakdown of SI (Kowyama et al., 1994a; Royo et al., 1994). Moreover, cytological and molecular genetic studies of x-ray irradiation-induced self-compatible mutants have uncovered a phenomenon, called competitive interaction, where duplication of the S-locus region renders pollen grains carrying two different pollen S-alleles unable to function in SI (de Nettancourt, 1977; Golz et al., 2000). Studies of self-compatible mutants have also led to the identification of loci unlinked to the S-locus that are required for the function of the S-RNase gene or the yet unidentified pollen S-gene. For example, mutations in the HT gene, which encodes a small Asn-rich protein (McClure et al., 1999), are partially responsible for the breakdown of SI in a cultivar of Lycopersicon esculentum (Kondo et al., 2002).

We have examined previously the SI status of all 19 natural taxa of the genus Petunia (Solanaceae; Tsukamoto et al., 1998), including three allopatric infraspecific taxa of the species Petunia axillaris (Lam.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenb., a historical parent of garden petunias (Sink, 1984). P. axillaris subsp. axillaris is self-incompatible, but subsp. parodii (Steere) Cabrera and subsp. subandina T. Ando (a recently described subspecies; Ando, 1996) are self-compatible. In Uruguay, subsp. axillaris and subsp. parodii show disjunctive distribution (Ando et al., 1994). From our survey of more than 100 natural populations of P. axillaris in Uruguay, we found that all populations of subsp. parodii were distributed in northern Uruguay and were entirely composed of self-compatible individuals. In contrast, all natural populations of subsp. axillaris were distributed in southern Uruguay and most of them were composed of only self-incompatible individuals. Some populations of subsp. axillaris contained both self-incompatible and self-compatible individuals (Ando et al., 1998), and they are referred to as “mixed populations.”

The mixed populations we have identified offer a good opportunity for studying the causes for the breakdown of SI. We previously analyzed the SI behavior of plants derived from a mixed population, designated U1, of subsp. axillaris, and showed that the breakdown of SI in the self-compatible individuals was caused by defects in the pistil function of an S-haplotype. Specifically, S13-RNase, the S13-allele product of the S-RNase gene, was absent. We have termed this phenomenon “stylar-part suppression (sps)” of an S-haplotype (Tsukamoto et al., 1999). We further showed that the failure to produce S13-RNase in the self-compatible individuals was not caused by deletion of the S13-RNase gene or by mutations in the promoter of the S13-RNase gene, but rather by a modifier locus that suppressed the expression of the S13-RNase gene (Tsukamoto et al., 2003).

Here, we report the study of another mixed population, designated U83, of subsp. axillaris. We identified two S-haplotypes, designated SC1 and SC2, that were associated with self-compatibility, and determined that SC2-haplotype was a mutant form of S17-haplotype we had identified previously in the U1 population, with the mutation affecting only the pollen function.

RESULTS

SI Status and S-Genotypes of 50 Plants of the U83 Population

We raised 50 plants (designated U83-1 to U83-50) from seeds collected from the U83 population and determined their SI status. Thirteen plants did not set any capsules upon self-pollination at the mature flower stage, whereas the other 37 plants set full-sized capsules, each containing approximately 900 seeds. For the former 13 plants, the growth of virtually all pollen tubes stopped in the upper third segment of their styles (results not shown), a typical response of solanaceous type SI. For the latter 37 plants, most of the pollen tubes reached the basal part of the style (results not shown), suggesting that their pistils failed to reject self-pollen. The ploidy level for all these 37 self-compatible plants was determined by flow cytometry as described by Tsukamoto et al. (1999), and all the plants were found to be diploid. This result ruled out polyploidy as a cause of the breakdown of SI in these self-compatible plants.

The S-genotypes of these 50 plants were determined as described in “Materials and Methods,” and the results are shown in Table I. A total of 14 different S-haplotypes were identified, and interestingly, two of them (S4 and S12) had previously been identified in the U1 population (Tsukamoto et al., 1999). The 12 “new” S-haplotypes were designated S19 through S28, SC1, and SC2. The haplotypes that occurred most frequently and second most frequently in these 50 plants were S21 (found in 12 plants) and S19 (found in 10 plants). S-homozygotes for all the 12 new haplotypes were generated by bud-selfing of appropriate U83 plants.

Table I.

S-genotypes of 50 individuals of P. axillaris subsp. axillaris derived from a mixed population (U83) in Uruguay

| Plant No. | SI or SCa | S-Genotype | Plant No. | SI or SC | S-Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U83-1 | SC | S19SC1 | U83-26 | SC | SC2SC2 |

| U83-2 | SC | S20SC2 | U83-27 | SI | S20S28 |

| U83-3 | SI | S21S22 | U83-28 | SC | SC1SC1 |

| U83-4 | SC | S20SC2 | U83-29 | SC | S19SC2 |

| U83-5 | SC | S21SC1 | U83-30 | SC | S19SC1 |

| U83-6 | SC | SC1SC1 | U83-31 | SC | SC2SC2 |

| U83-7 | SC | S21SC1 | U83-32 | SI | S19S21 |

| U83-8 | SI | S4S23 | U83-33 | SC | S26SC1 |

| U83-9 | SC | S19SC1 | U83-34 | SI | S4S23 |

| U83-10 | SC | S22SC1 | U83-35 | SC | S28SC2 |

| U83-11 | SC | S23SC2 | U83-36 | SC | SC1SC1 |

| U83-12 | SC | SC1SC1 | U83-37 | SI | S19S24 |

| U83-13 | SI | S21S24 | U83-38 | SC | S19SC1 |

| U83-14 | SC | SC1SC1 | U83-39 | SC | SC1SC1 |

| U83-15 | SC | S23SC2 | U83-40 | SC | S23SC1 |

| U83-16 | SC | S22SC1 | U83-41 | SI | S19S23 |

| U83-17 | SC | S21SC1 | U83-42 | SC | S21SC1 |

| U83-18 | SI | S19S25 | U83-43 | SC | S21SC1 |

| U83-19 | SC | SC1SC1 | U83-44 | SI | S21S26 |

| U83-20 | SC | S21SC1 | U83-45 | SC | S28SC1 |

| U83-21 | SI | S22S26 | U83-46 | SC | S4SC2 |

| U83-22 | SI | S12S27 | U83-47 | SC | S26SC1 |

| U83-23 | SI | S19S23 | U83-48 | SC | S21SC1 |

| U83-24 | SC | S21SC1 | U83-49 | SC | S23SC2 |

| U83-25 | SC | SC2SC2 | U83-50 | SC | SC2SC2 |

SC, Self-compatibility.

Stylar RNases Produced by Self-Compatible Plants and Their Progeny

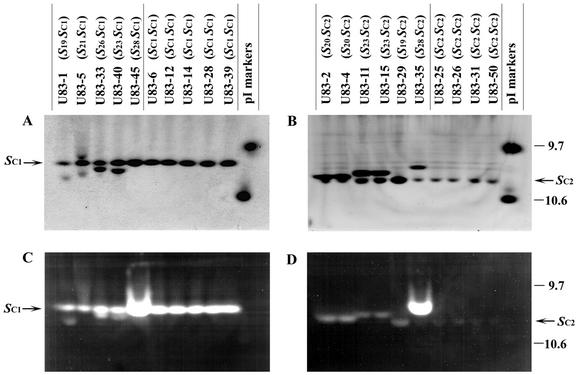

The total stylar protein of each of the 37 self-compatible plants was analyzed by isoelectric focusing (IEF). Twenty-five plants produced an RNase (designated SC1-RNase) with a pI of 10.0; the results of representative plants are shown in Figure 1, A and C. The other 12 self-compatible plants produced an RNase (designated SC2-RNase) with a pI of 10.3; the results of representative plants are shown in Figure 1, B and D. Some S-RNases had a similar pI as SC1- or SC2-RNase. For example, U83-45 produced a single intense RNase band, even though it carried S28- and SC1-haplotypes. It is interesting to note that none of the 37 self-compatible plants derived from the U83 population produced both SC1- and SC2-RNases, even though we were able to generate such plants by crossing an SC1SC1 plant with an SC2SC2 plant. As expected, all the progeny of this cross were self-compatible and produced both SC1- and SC2-RNases.

Figure 1.

IEF of representative self-compatible plants derived from the U83 population. Gels were subjected to Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (A and B) or RNase activity staining (C and D). The positions of SC1-RNase and SC2-RNase are indicated with arrows. The positions of pI markers are indicated to the right of the gels.

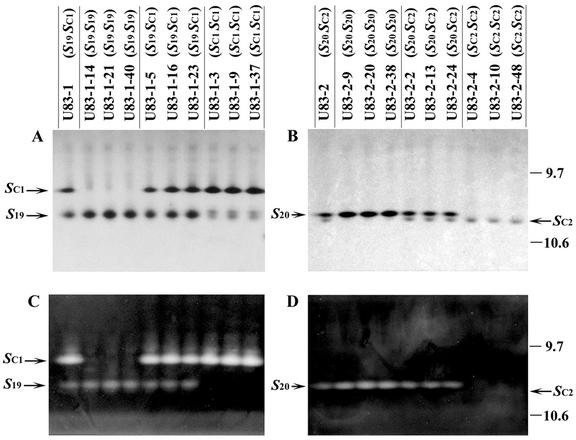

From the self-compatible plants that produced SC1-RNase, we chose U83-1, U83-6, U83-12, and U83-28 for bud-selfing, and examined the segregation of S-genotypes in each bud-selfed progeny. The genotype of U83-1 was S19SC1 (Table I), and it produced both S19-RNase (pI 10.3) and SC1-RNase (Fig. 2, A and C). The S-genotypes of 62 bud-selfed progeny plants of U83-1 were determined as described in “Materials and Methods”: eight were S19S19 (self-incompatible, rejecting S19 pollen but accepting SC1 pollen), 33 were S19SC1 (self-compatible, rejecting S19 pollen but accepting SC1 pollen), and 21 were SC1SC1 (self-compatible, accepting both S19 and SC1 pollen). For each of these three S-genotypes, total stylar protein was extracted from three plants and subjected to IEF. In all cases, the presence of SC1-RNase or S19-RNase in the style correlated with the plants carrying SC1- or S19-haplotype (Fig. 2, A and C), so these two RNases were the products of their respective S-haplotypes. SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the molecular masses of SC1- and S19-RNases were approximately 26.5 and 31.0 kD, respectively (results not shown), comparable with those of other S-RNases reported. Furthermore, all of the 40 progeny plants obtained from bud self-pollination of U83-1-3 (SC1SC1), a bud-selfed progeny plant of U83-1, were self-compatible. U83-6, U83-12, and U83-28 only produced the SC1-RNase, and all of the 30 bud-selfed progeny plants obtained from each plant were self-compatible and produced only the SC1-RNase (results not shown), consistent with the S-genotype of U83-6, U83-12, and U83-28 being SC1SC1.

Figure 2.

IEF of stylar RNases of U83-1, U83-2, and selected plants from their bud-selfed progeny. Gels were subjected to Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (A and B) or RNase activity staining (C and D). The positions of SC1-RNase and SC2-RNase are indicated with arrows. The positions of pI markers are indicated to the right of the gel.

For the self-compatible plants producing SC2-RNase, we chose U83-2, U83-25, and U83-26 for the segregation study. U83-2 produced two RNases, S20-RNase (pI 10.2) and SC2-RNase (Fig. 2, B and D). Among the 62 bud-selfed progeny plants of U83-2 examined, six were S20S20 (self-incompatible, rejecting S20 pollen but accepting SC2 pollen), 27 were S20SC2 (self-compatible, rejecting S20 pollen but accepting SC2 pollen), and 29 were SC2SC2 (self-compatible, accepting both S20 and SC2 pollen). IEF was carried out for the bud-selfed progeny of U83-2, and the presence of SC2-RNase and S20-RNase correlated with the presence of SC2-haplotype and S20-haplotype, respectively (Fig. 2, B and D). SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the molecular masses of SC2- and S20-RNases were approximately 26.0 and 29.0 kD, respectively (results not shown). As expected, all of the 40 progeny plants obtained from bud self-pollination of U83-2-4 (SC2SC2), a plant from the bud-selfed progeny of U83-2, were self-compatible. U83-25 and U83-26 plants produced only the SC2-RNase band, and the 30 bud-selfed progeny plants obtained from each plant were all self-compatible and produced only SC2-RNase (results not shown), consistent with the S-genotype of U83-25 and U83-26 being SC2SC2.

Reciprocal Crosses of SC1- and SC2-Homozygotes with 40 Tester S-Homozygotes

We chose U83-1-3 (SC1SC1) and U83-2-4 (SC2SC2) from the bud-selfed progeny of U83-1 and U83-2, respectively, to examine the genetic behavior of the SC1- and SC2-haplotypes. These two homozygotes were reciprocally crossed with 40 S-homozygotes, S1S1 through S40S40, of subsp. axillaris. U83-1-3 (SC1SC1) set full-sized capsules when pollinated with pollen from any of the 40 S-homozygotes, and reciprocal crosses also set full-sized capsules. For U83-2-4 (SC2SC2), all 40 S-homozygotes set full-sized capsules when pollinated with its pollen, and in reciprocal crosses, pollen from all but the S17S17 homozygote (U1-20-16) set full-sized capsules. That is, the SC2SC2 plant rejected S17 pollen, but its pollen was not rejected by the S17S17 homozygote. Interestingly, S17-haplotype was previously identified from another natural population, U1 (Tsukamoto et al., 1999), and it was not carried by any of the 50 plants of the U83 population examined (Table I).

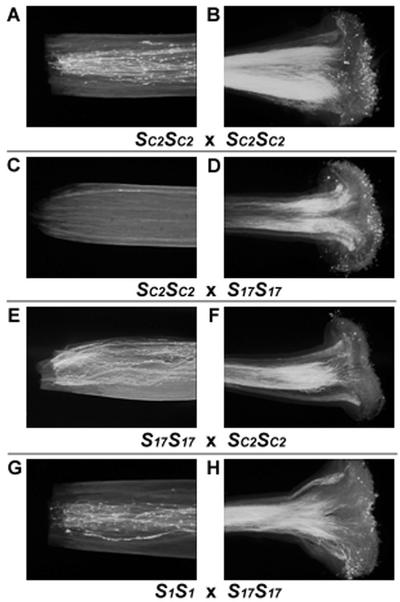

Growth of pollen tubes was examined 48 h after pollination of SC2SC2 (U83-2-4). When SC2SC2 was self-pollinated, a large number of pollen tubes reached the basal part of the style (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, upon self-pollination of the self-incompatible S17S17 plant (U1-20-16), the growth of pollen tubes was arrested in the upper third segment of the style (results not shown). When the pistils of SC2SC2 were pollinated with pollen from the S17S17 plant, the growth of pollen tubes was arrested in the upper third segment of the style (Fig. 3, C and D). In the reciprocal cross using the S17S17 plant as the pistil parent and SC2SC2 as the pollen parent, a large number of pollen tubes were able to reach the basal part of the style (Fig. 3, E and F). To confirm that the S17 pollen tubes grew normally in compatible crosses, we used pollen from the S17S17 plant to pollinate an S1S1 plant (U1-1-18). The results showed that all the S17 pollen tubes were able to grow to the basal part of the pistil of the S1S1 plant (Fig. 3, G and H).

Figure 3.

Observation by fluorescent microscopy of pollen tube growth in the stigmatic zone (B, D, F, and H) and in the basal region (A, C, E, and G) of the style 48 h after pollination.

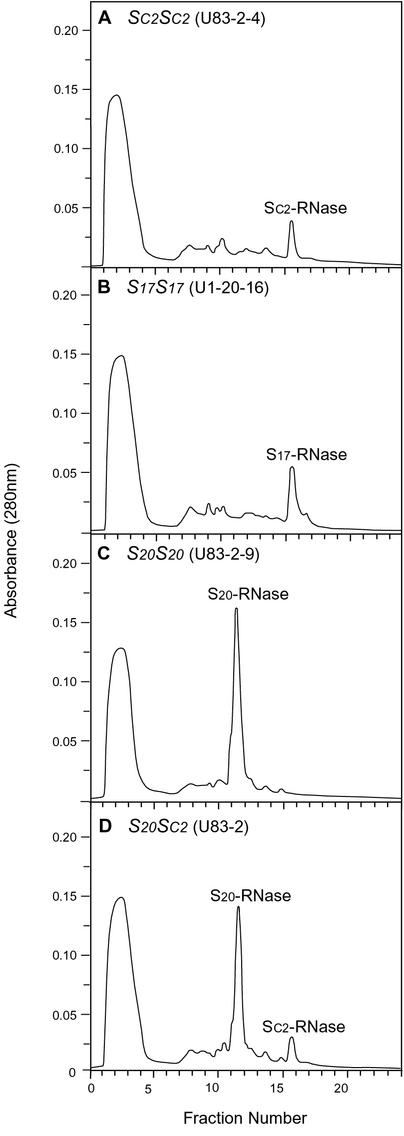

Properties of SC2- and S17-RNases

We next compared the stylar products of SC2-haplotype and S17-haplotype, i.e., SC2-RNase and S17-RNase. Total stylar protein of SC2SC2 (U83-2-4) and S17S17 (U1-20-16) plants were separated by Mono-S cation-exchange column chromatography. Both elution profiles contained one prominent peak at the same position (Fig. 4, A and B), typical of elution profiles of stylar proteins of self-incompatible Petunia spp. (Lee et al., 1994; Tsukamoto et al., 1999). To confirm that the common peak was SC2-RNase/S17-RNase, total stylar protein of S20S20 (U83-2-9) and S20SC2 (U83-2) was separately chromatographed (Fig. 4, C and D). Comparison of these profiles resulted in the positive assignment of the SC2-RNase/S17-RNase peak. We carried out RNase activity assays using the peak fractions of SC2-RNase (Fig. 4A) and S17-RNase (Fig. 4B) and found that the specific activity of SC2-RNase (130 A260 units min−1 mg−1) was almost identical to that of S17-RNase (134 A260 units min−1 mg−1).

Figure 4.

Cation-exchange chromatography profiles of style extracts from self-compatible SC2SC2 (A) and S20SC2 (D) plants and self-incompatible S17S17 (B) and S20S20 (C) plants.

Isolation of Full-Length cDNA Clones Encoding SC1-, SC2-, and S17-RNases

We first used RT-PCR to amplify partial-length cDNAs for SC1-, SC2-, and S17-RNases from poly(A+) RNA isolated from styles of U83-1-3 (SC1SC1), U83-2-4 (SC2SC2), and U1-20-16 (S17S17), respectively. The primers used corresponded to two of the conserved regions of solanaceous S-RNases, C2 (NFTIHGLWP), and C5 (ELNEIGICF; Tsai et al., 1992; Tsukamoto et al., 2003). An approximately 430-bp fragment of the expected size was obtained from all three plants. This fragment was purified and cloned for each S-RNase. Three separate cDNA libraries were constructed for these three plants using poly(A+) RNA isolated from stylar tissues collected 1 d before anthesis. Screening of the cDNA libraries using the cloned RT-PCR product obtained from each corresponding plant as a probe resulted in the isolation of three, six, and five positive clones from the SC1SC1, SC2SC2, and S17S17 cDNA libraries, respectively. The sequences of the longest clones for SC1-RNase (GenBank accession no. AY180048), SC2-RNase (GenBank accession no. AY180049), and S17-RNase (GenBank accession no. AY180050) were determined. Except for 2 additional bp in the 5′ non-coding region, the nucleotide sequence of the SC2-RNase cDNA was completely identical to that of the S17-RNase cDNA.

The deduced amino acid sequences of SC1-RNase and S17-RNase/SC2-RNase contained 221 and 220 residues, respectively. SC1-RNase was most similar to S1-RNase of P. axillaris subsp. axillaris, sharing 53.2% sequence identity (Tsukamoto et al., 2003), and S17-RNase was most similar with SX-RNase of Petunia hybrida Vilm., sharing 68.0% sequence identity (Ai et al., 1991).

Genetic Behavior of SC1- and SC2-Haplotypes

The SI behavior of SC1- and SC2-haplotypes was further examined in plants carrying the S13-haplotype. This haplotype was chosen because it was identified from a different population (U1), allowing us to determine whether SC1 and SC2 behaved similarly in a different genetic background. Moreover, S13-RNase had a lower pI than SC1- and SC2-RNases, so it could be easily distinguishable from the latter two by IEF. We reciprocally crossed U83-1-3 (SC1SC1), a plant from the bud-selfed progeny of U83-1, and U83-2-4 (SC2SC2), a plant from the bud-selfed progeny of U83-2, with U1-11-14 (S13S13). We analyzed 10 progeny (F1 generation) of each cross, and found all the F1 plants to be self-compatible. All the F1 plants of the reciprocal crosses between SC1SC1 and S13S13 accepted S17 pollen but rejected S13 pollen. All the F1 plants of the reciprocal crosses between SC2SC2 and S13S13 rejected both S13 and S17 pollen.

Next, we bud self-pollinated selected plants from each of the four F1 generations mentioned above and examined segregation of the S-haplotypes in their bud-selfed progenies (F2 generations). For SC1-haplotype, two F1 plants from SC1SC1 × S13S13 and two from the reciprocal cross were chosen, and a total of 231 individuals of the F2 generations of these four F1 plants were analyzed (Table II). The segregation ratio for each F2 generation was expected to be 1 (S13S13):2 (S13SC1):1 (SC1SC1). However, the S-genotypes of all except four plants were either S13SC1 (self-compatible, rejecting S13 pollen) or SC1SC1 (self-compatible, accepting S13 pollen), with more SC1SC1 individuals than S13SC1 individuals in all the F2 generations. The four S13S13 plants (self-incompatible, rejecting S13 pollen) were obtained only in two of the four F2 generations. One possibility for this large deviation from the expected segregation ratio is that not all S13 pollen tubes were able to escape rejection by the pistil during bud self-pollination. The immature buds (of 20 mm in length) of the F1 plants from SC1SC1 × S13S13 and S13S13 × SC1SC1 used for bud self-pollination were found by IEF to produce a small amount of S13-RNase in the style (results not shown). It should be noted that self-incompatible S13S13 progeny was never obtained when the S13SC1 plants were self-pollinated at the mature flower stage.

Table II.

Segregation of S-genotypes in bud-selfed progeny of F1 plants derived from reciprocal crosses between SC1SC1 and S13S13 plants

| S-Genotypes of F2 Progeny | F1 Progeny (Plant No.)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC1SC1 × S13S13 (no. 2) | SC1SC1 × S13S13 (no. 7) | SC1SC1 × S13S13 (no. 2) | S13S13 × SC1SC1 (no. 4) | |

| No. of plants (percentage of total) | ||||

| S13S13 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| S13SC1 | 10 (17.9) | 17 (28.8) | 26 (44.8) | 22 (37.9) |

| SC1SC1 | 46 (82.1) | 40 (67.8) | 30 (51.7) | 36 (62.1) |

| Total no. of plants | 56 | 59 | 58 | 58 |

For the SC2-haplotype, three F1 plants from the progeny of SC2SC2 × S13S13 and three from its reciprocal cross were chosen for analysis of their bud-selfed progenies (F2 generations). A total of 339 individuals in the F2 generations were analyzed (Table III). The S-genotypes of all but 10 plants were either S13SC2 (self-compatible, rejecting S13 and S17 pollen) or SC2SC2 (self-compatible, rejecting S17 pollen, accepting S13 pollen). The reason described above might explain the much lower than expected numbers of S13S13 plants (self-incompatible, rejecting S13, accepting S17 pollen) obtained, as well as the excess of SC2SC2 plants over S13SC2 plants.

Table III.

Segregation of S-genotypes in bud-selfed progeny of F1 plants derived from reciprocal crosses between SC2SC2 and S13S13 plants

| S-Genotypes of F2 Progeny | F1 Progeny (Plant No.)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC2SC2 × S13S13(no. 1) | SC2SC2 × S13S13(no. 6) | SC2SC2 × S13S13(no. 7) | S13S13 × SC2SC2(no. 1) | S13S13 × SC2SC2(no. 2) | S13S13 × SC2SC2(no. 3) | |

| No. of plants (percentage of total) | ||||||

| S13S13 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (1.7) | 4 (7.1) |

| S13SC2 | 17 (32.1) | 8 (14.3) | 13 (21.7) | 15 (26.8) | 13 (22.4) | 23 (41.1) |

| SC2SC2 | 36 (67.9) | 48 (85.7) | 45 (75.0) | 38 (67.8) | 44 (75.9) | 29 (51.8) |

| Total no. of plants | 53 | 56 | 60 | 56 | 58 | 56 |

All the genetic results obtained from the plants carrying SC1 or SC2 described in this section and earlier showed that the breakdown of SI in their self-compatible progeny cosegregated with SC1 or SC2, and that the pistil function of SC2 was normal and behaved as did S17. Thus, the defect in SC2 lay in the pollen function.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we studied the SI behavior of 50 plants derived from a mixed population, U83, of P. axillaris subsp. axillaris, with the goal of determining the cause of the breakdown of SI in the self-compatible individuals. We identified a total of 14 different S-haplotypes carried by these plants. The presence of this number of S-haplotypes in a small number of plants is typical of the highly polymorphic S-locus of all the SI systems studied so far. For example, 16 different S-haplotypes were identified from 41 plants of a natural population of Ipomoea trifida (Kowyama et al., 1994b), and 30 S-haplotypes were identified from 36 plants of a natural population of Papaver rhoeas (Lawrence and O'Donnell, 1981). In a previous study, we identified 18 different S-haplotypes from 33 plants derived from another mixed population, U1, of subsp. axillaris (Tsukamoto et al., 1999).

Interestingly, two of the S-haplotypes identified in the U83 population, S4 and S12, have been identified previously in the U1 population located approximately 100 km from the U83 population (Tsukamoto et al., 1999). However, it is not unusual to find genetically identical S-haplotypes in different natural populations. For example, Kowyama et al. (1994b) identified one S-haplotype of I. trifida from all six natural populations they examined (four in Mexico, one in Guatemala, and one in Colombia).

One major reason for studying mixed populations was to determine the causes of the breakdown of SI in naturally occurring self-compatible “mutants.” Some mutant S-haplotypes are likely to co-exist with their progenitor wild-type haplotypes in a natural population, making it possible to identify the cause of the breakdown of SI by genetic and molecular studies of self-compatible mutants and their wild-type progenitors. Analysis of self-incompatible individuals of L. peruvianum identified from the same locale as a self-compatible line that produced an S-RNase lacking the RNase activity have led to the identification of the progenitor haplotype of the self-compatible haplotype (Bernatzky et al., 1995). We have identified 13 mixed populations from a survey of 73 natural populations of subsp. axillaris (Ando et al., 1998). Our previous study of one mixed population, U1, has led to the identification of a mutant haplotype, designated S13sps, and its progenitor wild-type haplotype, S13. The cause of the mutant phenotype was attributed to a modifier locus that suppressed the expression of the S13-RNase gene in the style (Tsukamoto et al., 1999, 2003).

Here, we found that 37 of the 50 plants derived from the U83 population were self-compatible and that all the self-compatible plants carried one of two S-haplotypes, SC1 and SC2. The results of the genetic crosses of SC1 and SC2 homozygotes with all the functional S-genotypes we have identified in U1, U67, and U83 populations showed that none of the 12 functional S-haplotypes of the U83 population was the wild-type form of either SC1-haplotype or SC2-haplotype. The pollination results and the observation of pollen tube growth (Fig. 3) suggest that the SC2-haplotype is genetically identical to S17-haplotype except that it functions normally in the pistil but fails to function in the pollen. Interestingly, the S17-haplotype was identified from the U1 population (Tsukamoto et al., 1999).

That SC2-haplotype is defective in the pollen function of S17-haplotype was further confirmed by the characterization of SC2-RNase and S17-RNase and subsequent cloning and sequencing of their cDNAs. The sequences of these two S-RNases are completely identical, and both have normal RNase activity, which is required for rejection of self-pollen during the SI response (Huang et al., 1994).

The molecular nature of the mutation that affects the pollen function of S17-haplotype remains to be determined. Many pollen function mutants, either naturally occurring or induced by radiation, have been shown to be caused by duplication of the entire S-locus or the part of the S-locus that contains the pollen S-allele (de Nettancourt, 1977; Golz et al., 1999, 2001). The duplicated region often exists as a centric fragment but has been found translocated to a different chromosomal region or linked to the S-locus of another S-haplotype through unequal crossover (Golz et al., 2001). It is thought that pollen grains that contain two different S-alleles fail to function in SI interactions due to competitive interaction. For example, SI breaks down in an S1S2 plant with duplicated pollen S2-allele. If the duplicated region exists as a centric fragment, this plant will produce four different genotypes of pollen, S1, S2, S1dS2, and S2dS2 (with “d” standing for “duplicated,” as defined by Golz et al., 1999), but only S1dS2 pollen fails to function in SI interactions. Thus, self-compatible S1S1dS2 and S1S2dS2 progeny will be produced upon self-pollination at the mature flower stage. Bud-selfing, however, will also produce self-incompatible S1S1, S1S2, S2S2, and S2S2dS2 progeny. Similar results from ordinary selfing and bud-selfing will be obtained if the duplicated region is translocated to a chromosomal region unlinked to the S-locus. If the duplicated region is linked to the S1-locus, this plant will produce S1-dS2 (with the hyphen indicating linkage between the S1-locus and the duplicated S2-locus region) and S2 pollen, and ordinary selfing will produce self-compatible S1-dS2S2 and S1-dS2S1-dS2 progeny. Bud-selfing will also produce the self-incompatible S2S2 genotype.

All the results of bud-selfing we carried out in this work are consistent with the SC2-haplotype containing a duplicated S-locus region of unknown S-haplotype linked to the S17-locus. For example, bud-selfing of U83-2 (S20SC2) yielded self-incompatible S20S20, self-compatible SC2SC2, and self-compatible S20SC2, but did not result in self-incompatible S17S17 (i.e. SC2SC2 without the duplicated S-locus region) or self-incompatible S20S17, as would be expected if the duplicated S-locus region exists as a centric fragment or is translocated to a different chromosomal region. Thus, if the breakdown of SI in SC2-haplotype is caused by competitive interaction, duplication of the S-locus might have occurred in a plant carrying the S17-haplotype and some other S-haplotype, with the duplicated region of this other S-haplotype linked to the S17-locus. The genotype of U83-2 could be denoted as S20S17-dSn, and the genotype of its self-compatible SC2SC2 progeny would be S17-dSnS17-dSn.

The loss of pollen function could also be caused by mutation in the pollen S-gene, resulting in either complete absence of its protein product or production of a defective protein product. In the case of SC2, the mutation would specifically affect the pollen function of S17-haplotype. For example, the genotype of an S20SC2 plant could be denoted S20S17ppm, with S17ppm indicating pollen-part mutation of the pollen S17-gene. Bud-selfing will produce self-incompatible S20S20 progeny and self-compatible S20S17ppm and S17ppmS17ppm progeny. The results of all the genetic crosses involving the SC2-haplotype can be explained by the existence of S17ppm. However, it has been suggested that mutations in the pollen S-gene would be lethal to the pollen (Golz et al., 2001). A prevailing model explaining how S-haplotype-specific inhibition of pollen tubes can be achieved predicts that the pollen S-allele product contains an S-allele-specific domain and an RNase inhibitor domain and that the latter would interact with the RNase activity domain of all non-self S-RNases but not that of the self S-RNase (McCubbin and Kao, 2000). This would allow the self S-RNases, but not non-self S-RNases, to degrade pollen tube RNAs, leading to growth inhibition of self-pollen tubes. If this inhibitor model is correct, a pollen tube carrying a defective pollen S-allele would be unable to inhibit the RNase activity of any S-RNase and would suffer growth arrest in any style.

Luu et al. (2001) have proposed a modified inhibitor model that predicts that the pollen S-allele product only contains the S-allele specificity domain and that the RNase-inhibitor domain resides on a general RNase inhibitor. The RNase inhibitor would bind to all S-RNases except when an S-RNase is bound by its cognate pollen S-allele product. In the absence of a functional pollen S-allele product, the RNase activity of all S-RNases would be inhibited. Thus, contrary to the prediction of the simple inhibitor model, pollen carrying a defective pollen S-allele would not be lethal because it would be accepted by the pistil of any S-genotype.

Mutation in a modifier locus required for pollen function could also cause the breakdown of SI in SC2. If this is the case, the modifier locus would have to be tightly linked to the S-locus of the S17-haplotype. Otherwise, self-incompatible plants possessing the S17-haplotype would have been obtained in the bud-selfed (F2) progeny shown in Table III, had this modifier locus segregated away from the S-locus of the S17-haplotype. The existence of such a modifier locus for the pollen function is possible; however, as mentioned above, any mutation that affects the function of a pollen S-allele would be lethal to pollen if the simple inhibitor model of SI interactions is valid.

If the S-locus-linked markers previously identified in P. inflata (McCubbin et al., 2000) are also linked to the S-locus of P. axillaris, they will be useful for determining whether the SC2-haplotype contains duplication of the S-locus region of some other S-haplotype. Ultimately, identification of the pollen S-gene will reveal whether the defect in the pollen function of SC2 lies in the mutation in the pollen S17-gene.

Although all the properties of the SC1-haplotype determined in the present study resemble those of the SC2-haplotype, we could not conclude whether this haplotype is defective in the pistil function and/or pollen function. This is because we did not find the wild-type form of SC1 among the 40 S-haplotypes we have identified from the U1, U67, and U83 populations. It may be worthwhile searching for the wild-type form of the SC1-haplotype in the vast grassy plains of South America, particularly in Uruguay and Argentina, where P. axillaris widely occurs (Ando, 1996).

For the 13 mixed populations of P. axillaris we have identified, 10 contained mostly self-incompatible plants (Ando et al., 1998). For example, only 9% to 10% of the plants of the U1 population examined were self-compatible (Ando et al., 1998; Tsukamoto et al., 1999). The U83 population studied here was an exception: 61% (Ando et al., 1998) to 74% (Table I) of the plants studied were self-compatible. Breakdown of SI in all the self-compatible plants of the U1 population we studied was found to be caused by suppression of the stylar function of the S13-haplotype (Tsukamoto et al., 2003). However, the breakdown of SI in the self-compatible plants of the U83 population was caused by a defect in the pollen function of the S17-haplotype and another unknown mechanism associated with the SC1-haplotype. Multiple causes for the breakdown of SI may be a reason why the U83 population contained more self-compatible than self-incompatible individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Plants of Petunia axillaris subsp. axillaris derived from three different populations in Uruguay were used in the present study. They were U1 (located at 0.3 km east of La Paz along a side road leading to Camino Uruguay Road, Montevideo), U67 (located near Route 15, 10.1 km southeast of Rocha to La Paloma, Rocha Department), and U83 (located near Route 60, between Minas and Pan de Azúcar, Lavalleja Department). A total of 42 S-homozygotes were used: S1S1 to S18S18 were identified from the U1 population (Tsukamoto et al., 1999); S19S19 to S28S28, SC1SC1, and SC2SC2 were identified from the U83 population in this work (see below); and S29S29 to S40S40 were identified from the U67 population (T. Tsukamoto, T. Ando, T. Omori, H. Watanabe, H. Kokubun, E. Marchesi, and T.-h. Kao, unpublished data).

Examination of SI Behavior

The SI status of each plant was determined by the presence or absence of capsules after self-pollination at the mature flower stage. For bud self-pollination, several flower buds of 20 mm in length were emasculated and pollinated with fresh pollen collected from the same individual. For crosses, all flowers of the plants serving as females were carefully emasculated 1 d before anthesis and then pollinated with fresh pollen grains carrying selected S-haplotypes. The extent of pollen tube growth in the style was monitored 48 h after self-pollination using fluorescence microscopy after the style had been stained with decolorized aniline blue (Martin, 1959).

Analysis of Total Stylar Protein

IEF analysis of total protein extracted from the style (including stigma) was performed according to the method of Sassa et al. (1992). The methods for extracting total stylar protein, cation-exchange chromatography, and RNase activity assay were described by Tsukamoto et al. (1999). Stylar protein extracts were also analyzed by 12% (w/v) SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Laemmli, 1970).

Determination of S-Genotypes

Fifty individuals, designated U83-1 to U83-50, were raised from seeds collected from the U83 population. The procedure used in determining the S-genotypes is described below, using U83-1 as an example. U83-1 was bud self-pollinated to circumvent SI, and the SI status was examined for at least 30 plants of its bud-selfed progeny. One of the self-incompatible plants of its bud-selfed progeny was tentatively assigned SASA genotype, because its styles produced only one S-RNase as revealed by IEF. All the other individuals of the U83 population were then pollinated with pollen from the SASA plant to determine whether they carried the SA-haplotype. U83-1 turned out to be self-compatible because self-pollination of mature flowers also yielded large-sized capsules. Among the self-compatible plants of the bud-selfed progeny of U83-1, those whose styles produced a different S-RNase than SA-RNase and whose styles accepted pollen from the SASA plant were assigned SC1SC1; and those whose styles produced both SA- and SC1-RNases and rejected pollen from the SASA plant were assigned SASC1. IEF was used to determine whether the remaining self-compatible plants from the U83 population contained SC1-RNase.

When a self-compatible plant (e.g. U83-2) was found not to contain SC1-RNase, the method described above for U83-1 was used to determine the S-genotypes of its bud-selfed progeny and identify self-compatible homozygotes. Using U83-2 as an example, the S-genotype of self-compatible plants of its bud-selfed progeny that produced only one S-RNase band on IEF was assigned SC2SC2. The other S-haplotype carried by U83-2, which segregated to self-incompatible plants of its bud-selfed progeny, was tentatively assigned SB because plants homozygous for this haplotype accepted pollen from the SASA homozygote. Pollen from the SBSB homozygote was used to pollinate U83-3 through U83-50 to determine whether they carried the SB-haplotype. The above-mentioned process was repeated until the tentative S-genotypes of all U83 plants were determined.

To assign S-genotypes to the 50 U83 plants, each of the self-incompatible S-homozygotes (e.g. the SASA homozygote) obtained as described above was separately pollinated with pollen of the S1S1 through S18S18 homozygotes from the U1 population (Tsukamoto et al., 1999). If pollen of all the tester S-homozygotes was accepted by an S-homozygote derived from the U83 population, the S-haplotype carried by this S-homozygote was assigned Sn, with n being the number 19 or higher. In all, S19 to S28 were assigned to these S-homozygotes. In a separate study, 14 different S-homozygotes were identified from another mixed population, U67, and test crosses using pollen of S1S1 through S28S28 homozygotes showed that two of these S-haplotypes (S13 and S25) were present in the U67 population. Thus, the other 12 S-homozygotes were assigned S29 to S40.

Isolation of Total RNA from Styles

Total RNA was extracted from styles of flower buds 1 d before anthesis using the method described by Tsukamoto et al. (2003).

RT-PCR

The conditions for RT-PCR (including the primers used) and cloning of PCR products were as described by Tsukamoto et al. (2003). cDNAs were sequenced using the Thermo Sequenase Cycle Sequencing Kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and analyzed on an A.L.F. sequencer (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ).

Construction of cDNA Libraries and Isolation and Sequence Analysis of cDNA Clones

cDNA libraries were constructed from 10 μg of poly(A+) RNA isolated from styles of SC1SC1, SC2SC2, and S17S17 plants as described by Tsukamoto et al. (2003). Screening of the libraries using PCR-derived DNA fragments as probes, and sequencing of cDNA clones were carried out as described by Tsukamoto et al. (2003).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Masao Udagawa for assistance in surveying the native habitat of P. axillaris in Uruguay.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant no. IBN–9982659 to T.-h.K.) and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Research Fellowship for Young Scientists to T.T.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.102.018069.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ai Y, Kron E, Kao T-h. S-alleles are retained and expressed in a self-compatible cultivar of Petunia hybrida. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:353–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00280291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando T. Distribution of Petunia axillaris (Solanaceae) and its new subspecies in Argentina and Bolivia. Acta Phytotaxon Geobot. 1996;47:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ando T, Iida S, Kokubun H, Ueda Y, Marchesi E. Distribution of infraspecific taxa of Petunia axillaris (Solanaceae) in Uruguay as revealed by discriminant analyses. Acta Phytotaxon Geobot. 1994;45:95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ando T, Tsukamoto T, Akiba N, Kokubun H, Watanabe H, Ueda Y, Marchesi E. Differentiation in the degree of self-incompatibility in Petunia axillaris (Solanaceae) occurring in Uruguay. Acta Phytotaxon Geobot. 1998;49:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bernatzky R, Zhang Y, Hackett GR, Glaven RH. Identification of the self-incompatibility progenitor alleles of the self-compatible mutation in Lycopersicon peruvianum. Rep Tom Genet Coop. 1995;45:13. [Google Scholar]

- de Nettancourt D. Incompatibility in angiosperms. In: Frankel R, Gall GAE, Grossman M, Linskens HF, de Zeeuw D, editors. Monographs on Theoretical and Applied Genetics. Vol. 3. Berlin: Springer; 1977. pp. 1–140. [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Lee H-S, Karunanandaa B, Kao T-h. Ribonuclease activity of Petunia inflata S proteins is essential for rejection of self-pollen. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1021–1028. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.7.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golz JF, Clarke AE, Newbigin E. Mutational approaches to the study of self-incompatibility: revisiting the pollen-part mutants. Ann Bot Suppl. 2000;85:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Golz JF, Oh H-Y, Su V, Kusaba M, Newbigin E. Genetic analysis of Nicotiana pollen-part mutants is consistent with the presence of an S-ribonuclease inhibitor at the S locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15372–15376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261571598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golz JF, Su V, Clarke AE, Newbigin E. A molecular description of mutations affecting the pollen component of the Nicotiana alata S locus. Genetics. 1999;152:1123–1135. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Yamamoto M, Matton DP, Sato T, Hirai M, Norioka S, Hattori T, Kowyama Y. Cultivated tomato has defects in both S-RNase and HT genes required for stylar function of self-incompatibility. Plant J. 2002;29:627–636. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowyama Y, Kunz C, Lewis I, Newbigin E, Clarke AE, Anderson MA. Self-incompatibility in a Lycopersicon peruvianum variant (LA2157) is associated with a lack of style S-RNase activity. Theor Appl Genet. 1994a;88:859–864. doi: 10.1007/BF01253997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowyama Y, Takahasi H, Muraoka K, Tani T, Hara K, Shiotani I. Number, frequency and dominance relationships of S-alleles in diploid Ipomoea trifida. Heredity. 1994b;73:275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MJ, O'Donnell S. The population genetics of the self-incompatibility polymorphism in Papaver rhoeas: III. The number and frequency of S-alleles in two further natural populations (R102 and R104) Heredity. 1981;47:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-S, Hung S, Kao T-h. S proteins control rejection of incompatible pollen in Petunia inflata. Nature. 1994;367:560–563. doi: 10.1038/367560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu D-T, Qin X, Laublin G, Yang Q, Morse D, Cappadocia M. Rejection of S-heteroallelic pollen by a dual-specific S-RNase in Solanum chacoense predicts a multimeric SI pollen component. Genetics. 2001;159:329–335. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.1.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin FW. Staining and observing pollen tubes in the style by means of fluorescence. Stain Technol. 1959;34:125–128. doi: 10.3109/10520295909114663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure B, Mou B, Canevascini S, Bernatzky R. A small asparagine-rich protein required for S-allele-specific pollen rejection in Nicotiana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13548–13553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin AG, Kao T-h. Molecular recognition and response in pollen and pistil interactions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:333–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin AG, Wang X, Kao T-h. Identification of self-incompatibility (S-) locus linked pollen cDNA markers in Petunia inflata. Genome. 2000;43:619–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo J, Kunz C, Kowyama Y, Anderson MA, Clarke AE, Newbigin E. Loss of a histidine residue at the active site of S-locus ribonuclease is associated with self-incompatibility in Lycopersicon peruvianum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6511–6514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa H, Hirano H, Ikehashi H. Self-incompatibility-related RNases in styles of Japanese pear (Pyrus serotina Rehd.) Plant Cell Physiol. 1992;33:811–814. [Google Scholar]

- Sink KC. Taxonomy. In: Sink KC, editor. Petunia. Berlin: Springer; 1984. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai D-S, Lee H-S, Post LC, Kreiling KM, Kao T-h. Sequence of an S-protein of Lycopersicon peruvianum and comparison with other solanaceous S-proteins. Sex Plant Reprod. 1992;5:256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto T, Ando T, Kokubun H, Watanabe H, Masada M, Zhu X, Marchesi E, Kao T-h. Breakdown on self-incompatibility in a natural population of Petunia axillaris (Solanaceae) in Uruguay containing both self-incompatible and self-compatible plants. Sex Plant Reprod. 1999;12:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto T, Ando T, Kokubun H, Watanabe H, Sato T, Masada M, Marchesi E, Kao T-h. Breakdown of self-incompatibility in a natural population of Petunia axillaris caused by a modifier locus that suppresses the expression of an S-RNase gene. Sex Plant Reprod. 2003;15:255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto T, Ando T, Kokubun H, Watanabe H, Tanaka R, Hashimoto G, Marchesi E, Kao T-h. Differentiation in the status of self-incompatibility among all natural taxa of Petunia (Solanaceae) Acta Phytotaxon Geobot. 1998;49:115–133. [Google Scholar]