Abstract

Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 proteins are considered to be key mediators of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling. However, the identities of the Smad partners mediating TGF-β signaling are not fully understood. Here, we show that RNA-binding protein with multiple splicing (RBPMS), a member of the RNA-binding protein family, physically interacts with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 both in vitro and in vivo. The presence of TGF-β increases the binding of RBPMS with these Smad proteins. Consistent with the binding results, overexpression of RBPMS enhances Smad-dependent transcriptional activity in a TGF-β-dependent manner, whereas knockdown of RBPMS decreases this activity. RBPMS interacts with TGF-β receptor type I (TβR-I), increases phosphorylation of C-terminal SSXS regions in Smad2 and Smad3, and promotes the nuclear accumulation of the Smad proteins. Moreover, RBPMS fails to enhance the transcriptional activity of Smad2 and Smad3 that lack the C-terminal phosphorylation sites. Our data provide the first evidence for an RNA-binding protein playing a role in regulation of Smad-mediated transcriptional activity and suggest that RBPMS stimulates Smad-mediated transactivation possibly through enhanced phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 at the C-terminus and promotion of the nuclear accumulation of the Smad proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is a ubiquitously expressed cytokine that regulates a variety of biological processes, including cell growth, differentiation, matrix production, apoptosis and development (1–3). TGF-β signaling is initiated by ligand binding to the transmembrane receptor serine–threonine kinases, TGF-β receptor type I (TβR-I) and type II (TβR-II). Binding of TGF-β to TβR-II induces formation of heteromeric complexes of TβR-I and TβR-II. TβR-II then activates TβR-I by phosphorylating the glycine–serine domain of TβR-I. The activated TβR-I phosphorylates receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads), including Smad2 and Smad3 in TGF-β signaling, thereby promoting their open conformation. In this state, these receptor-activated Smads can form complexes with a common mediator Smad, Smad4, and translocate to the nucleus, where they bind DNA and regulate transcription of TGF-β responsive target genes.

Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 are considered to be key mediators of TGF-β signaling (4,5). These Smad proteins contain highly conserved N- and C-terminal domains, known as the Mad homology 1 (MH1) and Mad homology 2 (MH2) domains, respectively. Between these two domains is the linker region rich in proline residues. The MH1 domain is responsible for DNA binding, whereas the MH2 domain is endowed with transcriptional activation properties. Smad2 and Smad3 can be phosphorylated both at the C-terminal SSXS regions and at the linker region. In contrast to Smad2 and Smad3, Smad4, a protein of 552 amino acids, is not regulated by phosphorylation, but acts as a central mediator of TGF-β signaling. The Smad4 C-terminal domain (amino acids 260–552), when fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain, can stimulate transcription, suggesting that it may contain transactivation activity (6). Alterations in Smad2 and Smad4 genes have been found to associate with many types of human cancers, and thus Smads are considered to be important tumor suppressors (7,8). Numerous transcription factors and coregulators have been recently identified to interact with Smads and regulate the signaling outcome (9,10). They include the AP-1 family (11–13), steroid receptor family (14), CBP/p300 (15), P/CAF (16), TGIF (17), Ski (18,19), SnoN (20), SNIP1 (21) and many others. The Smad transcriptional complexes can regulate transcription both positively and negatively. Although many proteins have been known to regulate TGF-β signaling, the intracellular signaling pathways modulating TGF-β responsive gene expression are not fully elucidated.

Using a lac operator/repressor tethering system (22), we previously demonstrated that the Smad4 C-terminal region (amino acids 260–514) can mediate large-scale chromatin unfolding in mammalian cells, suggesting that the region 260–514 of Smad4 plays an important role in gene transcription (23). To search for proteins responsible for Smad4-mediated transcription, we have performed yeast two-hybrid screens using amino acids 260–514 of Smad4 as bait, and identified RNA-binding protein with multiple splicing (RBPMS) as a novel Smad4-interacting protein. RBPMS is a member of one of the largest families of RNA-binding proteins, the RNA Recognition Motif (RRM) family (24). RBPMS contains a single RRM domain at the N-terminus and is human homologue of Xenopus hermes (25–28). However, the function of RBPMS is unknown. Here, we show that RBPMS physically interacts with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 in vitro and in vivo. Overexpression of RBPMS enhanced Smad-mediated transcriptional activity, whereas knockdown of endogenous RBPMS with small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly inhibits the transcriptional activity. RBPMS increases Smad-mediated transcriptional activity possibly through increased phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 at the C-terminal SSXS regions and promotion of the nuclear accumulation of the Smad proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The reporter constructs p3TP-Lux (29) and lac-Luc (22) have been described previously. The TβR-I expression vector is a gift from Dr Mark C. Wilkes (30). The entire coding sequences of Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 were isolated from human embryonic kidney 293T cells by RT–PCR, and cloned in frame into a pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) or the pcDNA3 linked with Escherichia coli lac repressor at the N-terminus. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged fusion protein constructs were made by inserting PCR-amplified Smad cDNA fragments into pEGFP-C1 (Clontech). The mammalian expression vectors for RBPMS and its deletion mutants were constructed by amplification of each sequence by standard PCR or recombinant PCR methods, and the resulting fragments were inserted in frame into the pcDNA3 linked with FLAG at the N-terminus. Prokaryotic vectors encoding GST- and His-tagged fusion proteins were prepared by PCR amplification of each sequence, and the resulting fragments were cloned in frame into pGEX-KG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and pET28a (Novagen), respectively. For the yeast two-hybrid assay, the bait plasmid pGBKT7-Smad4 (260–514) was generated by inserting a PCR-amplified cDNA fragment containing most of the MH2 domain of Smad4 into pGBKT7 (Clontech). All plasmids were verified by restriction enzyme analysis and DNA sequencing. Details of cloning are available upon request.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

The bait plasmid pGBKT7-Smad4 (260–514) was used to screen a human mammary gland cDNA library fused to the GAL4 activation domain in pACT2 (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transformants were plated on synthetic medium lacking tryptophan, leucine, adenine and histidine but containing 1 mM 3-aminotriazole. Approximately 0.8 million transformants were screened. The screened positive clones were also verified by one-on-one transformations and selection on agar plates lacking tryptophan and leucine, or adenine, histidine, tryptophan and leucine, respectively, and were also processed by β-galactosidase assay.

GST pull-down assay

The GST- and His-tagged fusion proteins were expressed and purified by glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia) and Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen), respectively. The expression plasmid for RBPMS was used for in vitro transcription and translation in the TNT system (Promega). The 35S-labeled RBPMS or the purified His-tagged fusion protein was incubated with GST fusion protein bound to glutathione–Sepharose beads in 0.5 ml of the binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40) at 4°C. The beads were precipitated, washed four times with the binding buffer, eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE. The gel was then dried and exposed to X-ray film overnight, or western blot was performed using anti-His (Amersham Pharmacia).

Antibody production

The GST-RBPMS (130–220) fusion protein was expressed in bacteria and purified using glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads according to the manufacturer's protocol (Amersham Pharmacia). To generate polyclonal RBPMS antibody, the purified GST-RBPMS (130–220) protein were injected subcutaneously into each of two BALB/c female mice. Sera from the immunized mice were collected and purified by affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce).

Co-immunoprecipitation

For transfection-based co-immunoprecipitation assays, 293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), lysed in 0.5 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% NP-40, 1 mM DTT and protease inhibitor tablets from Roche), and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 h at 4°C. The beads were washed four times with the lysis buffer, and eluted in SDS sample buffer. The eluted proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE, followed by western blotting with anti-GFP (Clontech) or anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich) antibody.

For detecting interaction of endogenous Smad4 with RBPMS, cells were lysed in 0.5 ml lysis buffer and immunoprecipitated with anti-Smad4 or control serum (Santa Cruz). After extensive washing with the lysis buffer, the immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS–PAGE, followed by western blot analysis using the anti-RBPMS.

Reporter assay

293T cells were transfected with the p3TP-Lux or lac-Luc reporter, β-galactosidase reporter, and the indicated expression vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After transfection, cells were treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 20 h in medium containing 0.5% FBS or in serum-free medium. To test the role of autocrine TGF-β in TGF-β signaling, either control IgG or TGF-β neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems) was added to the culture. β-galactosidase reporter was used as an internal control. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were determined as described previously (31). All experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

siRNA experiments

siRNA was designed using the web-based insert design tool at www.ambion.com/techlib/misc/psilencer_converter.html. The pSilencer2.1-U6neo vector (Ambion)-based siRNA was made according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA target sequences of siRNAs for RBPMS were AACATACCAACCTACTGCAGA (RBPMS siRNA1) and AAACACTACGACTAGAGTTTG (RBPMS siRNA2), respectively. Plasmid pSilencer2.1-U6 neo Negative Control (Ambion) was used as a control vector. Transient transfections of the vector-based siRNAs into 293T cells were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and the cells were harvested at different hours after transfection.

Kinase assays

293T cells were transfected with expression vector for FLAG-tagged RBPMS or empty vector in the absence or presence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 in combination with 10 μM TβR-I inhibitor SB-431542. The transfected cells were lysed in 0.5 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% NP-40, 1 mM DTT and protease inhibitor tablets from Roche), and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich). Immune complexes were washed three times in kinase assay buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2.5 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM Na3VO3, 1 mM NaF). Pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of kinase assay buffer supplemented with 5 μCi of γ-32P-ATP and 5 μg of purified His-tagged Smad2 or Smad3 or their mutants. Assays were performed at 30°C for 30 min and then were stopped by addition of SDS loading buffer. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography.

Subcellular fractionation

Cells were homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer in 1 ml of Buffer A (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, with a cocktail of protease inhibitors from Roche). Thehomogenate was centrifuged at 366 g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed once with Buffer A, resuspended in SDS loading buffer, and analyzed as the nuclear fraction. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 13 201 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the final supernatant analyzed as the cytoplasmic fraction. The total protein concentrations of different fractions were determined by the BCA protein assay method (Pierce). An equal amount of total proteins was analyzed by SDS–PAGE followed by western blotting.

Poly(U) RNA pull-down assay

The poly(U) RNA pull-down assay was performed essentially as described by Babic et al. (32). Briefly, cell lysates were incubated with poly(U) agarose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), or agarose beads alone (Santa Cruz Biotech), for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed with lysis buffer and resuspended in SDS–PAGE sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibody.

RESULTS

Identification of RBPMS as a Smad4-interacting protein by yeast two-hybrid system

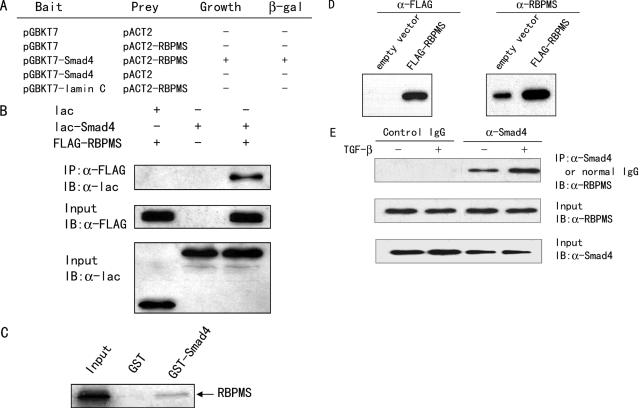

To identify novel Smad4-interacting proteins, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screening of a human mammary cDNA library using amino acids 260–514 containing most of the Smad4 MH2 domain as bait. Screening of ∼0.8 million transformants resulted in the isolation of several positive clones. Sequencing of the positive clones identified several clones that encoded the full-length cDNA of RBPMS gene. To further confirm the interaction of RBPMS with Smad4 in yeast, we transformed RBPMS in pACT2 vector harboring GAL4 activation domain or pACT2 vector, together with Smad4(260–514) in pGBKT7 vector harboring GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) or together with an unrelated protein, lamin C, fused to the GAL4 DBD. The transformed colonies with RBPMS and Smad4(260–514) showed both the ability to grow in medium lacking adenosine, histidine, tryptophan and leucine, and to turn blue in a β-galactosidase assay, whereas cotransfections with the control vectors did not do so (Figure 1A). These data demonstrated that RBPMS interacts with Smad4 in yeast cells.

Figure 1.

RBPMS interacts with Smad4 in yeast, in mammalian cells and in vitro. (A) Identification of RBPMS as a Smad4-interacting protein by the yeast two-hybrid assay. Yeast AH109 cells were transformed with different plasmids and grown on SD/−Trp−Leu−His−Ade. +, grown within 96 h; −, no growth within 96 h. Positive colonies were tested for β-galactosidase activity. +, turned blue within 2 h; −, did not turn blue within 2 h. (B) Interaction of RBPMS with Smad4 in mammalian cells. 293T cells, cultured in regular medium, were transfected with expression plasmids as indicated. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-lac polyclonal antibody (Stratagene). (C) Interaction of RBPMS with Smad4 in vitro. Glutathione–Sepharose beads bound with GST-Smad4 or with GST were incubated with 35S-labeled RBPMS. After washing the beads, the bound proteins were eluted and subjected to SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. (D) Characterization of anti-RBPMS mouse antiserum by immunoblotting. The lysates from 293T cells transfected with FLAG-RBPMS or its empty vector were prepared and the proteins detected with anti-FLAG (left panel) or anti-RBPMS (right panel) antibody. (E) Interaction of endogenous RBPMS with Smad4 in vivo. 293T cells, cultured in serum-free medium, were treated without and with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 1 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either anti-Smad4 antibody or preimmune control serum (Santa Cruz). The precipitates were analyzed by immunoblot using anti-RBPMS.

Interaction of RBPMS with Smad4 in vivo and in vitro

To confirm the interaction between RBPMS and Smad4, we next examined the ability of RBPMS protein to bind to Smad4 in mammalian cells. 293T cells were co-transfected with FLAG-tagged RBPMS, E.coli lac repressor (lac)-tagged Smad4, or lac control vector. Immunoprecipitation (IP) of cell lysates with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody was followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-lac. Results showed a specific interaction between the FLAG-RBPMS and lac-Smad4 (Figure 1B). To demonstrate the interaction of RBPMS and Smad4 in vitro, GST pull-down assays were performed in which in vitro translated 35S-methionine-labeled RBPMS was incubated with full-length GST-Smad4 or GST. As shown in Figure 1C, RBPMS interacted with GST-Smad4 but not with GST alone. These results indicate that RBPMS interacted with Smad4 in vivo and in vitro.

As an initial step to examine if RBPMS physiologically interacts with Smad4, mouse RBPMS polyclonal antibody, which is not commercially available, was developed. To determine the specificity of the anti-RBPMS antibody, 293T cells were transfected with expression vector for FLAG-tagged RBPMS or its empty vector control. Immunoblotting of whole cell extracts with anti-FLAG demonstrated a single band with a molecular weight of ∼25 kDa in 293T cells transfected with the FLAG-tagged RBPMS construct but not in cells transfected with the control vector (Figure 1D, left panel), whereas immunoblotting with anti-RBPMS showed a single band both in 293T cells transfected with the FLAG-tagged RBPMS construct and in 293T cells transfected with the control vector (Figure 1D, right panel). However, the intensity of the band in 293T cells transfected with the FLAG-tagged RBPMS construct was much stronger than that in 293T cells transfected with the control vector, indicating that 293T cells expressed endogenous RBPMS. Due to the small size of the FLAG tag, FLAG-tagged RBPMS could not be clearly distinguished from endogenous RBPMS. Detection of FLAG-tagged RBPMS was completely blocked by pre-incubating anti-RBPMS with the cognate GST-RBPMS fusion protein but not by pre-incubating with GST (data not shown). These data indicate that anti-RBPMS specifically recognizes RBPMS.

To ascertain the interaction of RBPMS with Smad4 in a more physiological context, the endogenous Smad4 protein from 293T cells was immunoprecipitated with an anti-Smad4 antibody. Subsequent immunoblotting with anti-RBPMS antibody indicated that the endogenous RBPMS was coprecipitated with Smad4 (Figure 1E) in both the absence and presence of TGF-β1. However, addition of TGF-β1 enhanced the interaction of Smad4 with RBPMS. In the negative control experiment, normal mouse serum or an irrelevant antibody, anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody, did not immunoprecipitate RBPMS (Figure 1E and data not shown). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that RBPMS interacts with Smad4 under physiological condition.

Mapping of the Smad4 and RBPMS interaction regions

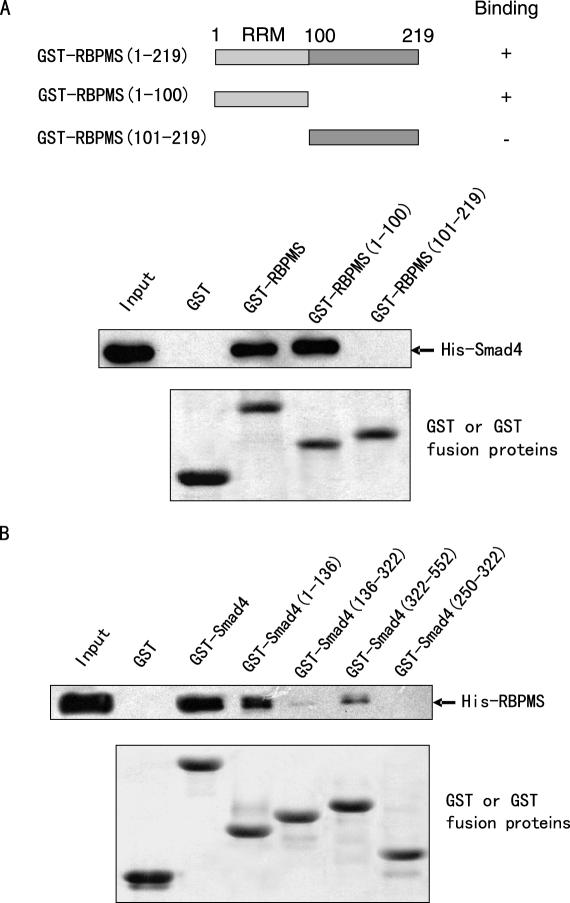

To define the region of RBPMS required for its interaction with Smad4, GST pull-down experiments were performed in which two deletion mutants, GST-RBPMS(1–100) containing the RRM and GST-RBPMS(101–219), were incubated with purified His-tagged Smad4. As shown in Figure 2A, the GST-RBPMS(1–100) bound specifically to Smad4, but the GST-RBPMS(101–219) and GST did not, suggesting that the RRM region is required for the interaction with Smad4.

Figure 2.

Mapping of the RBPMS and Smad4 interaction regions. (A) Mapping of Smad4 interaction region in RBPMS. Purified His-Smad4 was incubated with full-length GST-RBPMS, GST-RBPMS(1–100) or GST-RBPMS(101–219), or with GST. The bound proteins were subjected to SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-His antibody (Amersham Pharmacia). Also presented is a schematic diagram of the RBPMS protein, illustrating the location of the RNA recognition motif (RRM). SDS–PAGE analysis of the purified GST-fusion proteins is shown at the bottom. (B) Mapping of RBPMS interaction region in Smad4. Purified His-RBPMS was incubated with full-length GST-Smad4, GST-Smad4(1–136), GST-Smad4(136–322), GST-Smad4(322–552) or GST-Smad4(250–322), or with GST. Bound proteins were detected by immunoblotting using anti-His antibody. SDS–PAGE analysis of the purified GST-fusion proteins is shown at the bottom.

To define the binding region or regions of Smad4 that are important for RBPMS interaction, Smad4 encompassing different regions, including the N-terminal MH1 domain [GST-Smad4(1–136)], the central linker region [GST-Smad4(136–322)], the C-terminal MH2 domain [GST-Smad4(322–552)], and the partial linker region [GST-Smad4(250–322)], was generated (Figure 2B). The results of the GST pull-down assays indicated that both MH1 and MH2 domains interacted with RBPMS, with the MH1 displaying higher binding affinity, whereas the linker regions, including GST-Smad4(136–322) and GST-Smad4(250–322), had negligible binding ability.

Interaction of RBPMS with Smad2 and Smad3 in vivo and in vitro

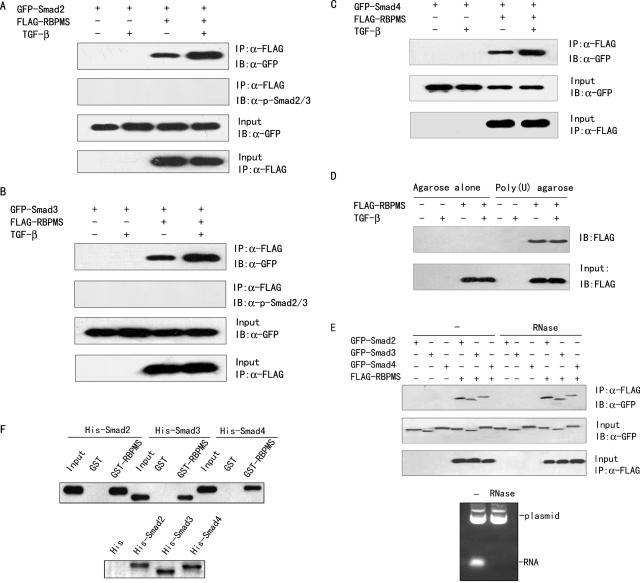

Since RBPMS was shown to interact with both the MH1 and the MH2 domains of Smad4, which are two highly conserved domains among Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4, the specificity of the interaction between RBPMS and Smad4 was determined by co-immunoprecipitaion experiments. FLAG-tagged RBPMS and GFP-tagged Smad2, Smad3 or Smad4 were cotransfected into 293T cells. Cells were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with FLAG antibody-conjugated agarose beads followed by immunoblot with GFP antibody. As shown in Figure 3A–C, all of the Smad proteins could be co-immunoprecipitated in the presence, but not in the absence, of FLAG-RBPMS, with or without exogenous TGF-β1. In all cases, however, TGF-β1 increased the interaction of RBPMS with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 in vivo. Furthermore, RBPMS did not associate with Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylated on their C-terminal SSXS motif (Figure 3A and B), as measured by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-Smad2/3(Ser423/425), which recognizes Smad3 phosphorylated at Ser-423 and Ser-425 and corresponding phosphorylated Smad2 (Ser-465 and Ser-467).

Figure 3.

RBPMS interacts with Smads in vivo and in vitro. (A–C) Interaction of RBPMS with Smads in vivo. FLAG-tagged RBPMS and GFP-tagged Smad2, Smad3 or Smad4 were cotransfected into 293T cells in the presence or absence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and the precipitates were then immunoblotted (IB) with anti-GFP antibody (Clontech) or anti-phospho-Smad2/3(Ser423/425) antibody (Santa Cruz). (D) Association of RBPMS with poly(A) RNA in vivo. 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged RBPMS or empty vector in the presence or absence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. Cell lysates were used for poly(U) RNA agarose or agarose alone pull-down assays. After pull-downs, the RBPMS protein was detected with anti-FLAG antibody. The RBPMS in the cell lysates prior to pull-downs is used as an input. (E) Effect of RNA on the interaction of RBPMS with Smads in vivo. 293T cells were transfected in the presence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 and analyzed as in (A–C) except that cell lysates were treated with 100 μg/ml RNase before immunoprecipitation (upper panel). The isolated plasmid without RNase treatment was used as a control for RNase efficiency (lower panel). (F) Direct interaction of RBPMS with Smads. E.coli-expressed His-Smad2, His-Smad3 and His-Smad4 were purified, and incubated with purified GST or GST-RBPMS immobilized on glutathione–Sepharose beads. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-His antibody (upper panel). SDS–PAGE analysis of the purified His-fusion proteins is shown at the bottom.

To examine whether the interaction of RBPMS with the Smad proteins is mediated by RNA, the ability of RBPMS to bind to RNA was first determined by poly(U) RNA pull-down experiments. Consistent with previous report demonstrating that hermes, the Xenopus homolog of RBPMS, can associate with poly(A) RNA in vivo, RBPMS can also efficiently bind to RNA (Figure 3D). However, the in vivo interaction of RBPMS with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 was unlikely to be mediated by RNA, as it was not affected by RNase treatment prior to immunoprecipitation (Figure 3E, upper panel), although RNase could efficiently digest RNA (Figure 3E, lower panel).

To test if RBPMS can interact directly with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4, purified GST-RBPMS was mixed with purified His-tagged Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 in binding assays. Consistent with the in vivo results, all of the Smad proteins directly interacted with RBPMS (Figure 3F). Taken together, these data suggest that conserved amino acids of the Smad proteins may be responsible for the interaction of RBPMS with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4.

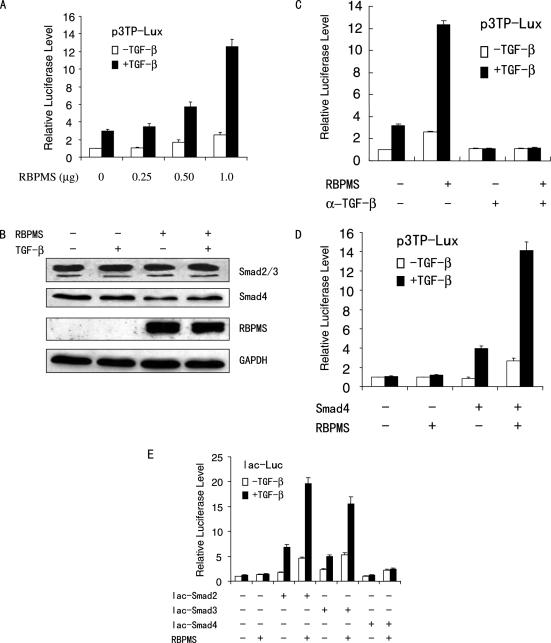

Overexpression of RBPMS enhances TGF-β/Smad-mediated transactivation

To determine the effects of RBPMS on TGF-β/Smad-mediated transcription, 293T cells were cotransfected with the synthetic TGF-β-responsive transcriptional reporter p3TP-Lux and increasing amounts of RBPMS. As shown in Figure 4A, in both the absence and presence of exogenous TGF-β, RBPMS stimulated the reporter gene transcription in a dose-dependent manner. Consistent with the binding results, the magnitude of the reporter activation in the presence of TGF-β1 was greater than that in the absence of TGF-β1. RBPMS did not increase the protein levels of Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 (Figure 4B), suggesting that this enhanced transcriptional activity was not a result of increased Smad protein production.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of RBPMS increases TGF-β/Smad-mediated transactivation. (A) 293T cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of reporter p3TP-Lux and increasing amounts of plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged RBPMS. Cells were treated with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 and analyzed for luciferase activity. (B) Western blotting showing the Smad2, Smad3, Smad4 and RBPMS protein levels. 293T cells were transfected as in panel A. Cell lysates were prepared from 293T cells transfected with 1 μg of the RBPMS expression vector, and were probed with anti-Smad2/3, anti-Smad4, anti-FLAG, or anti-GAPDH. (C) 293T cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of p3TP-Lux and 1.0 μg of the expression vector of RBPMS in the absence or presence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 with or without 10 μg/ml TGF-β neutralizing antibody (α-TGF-β). The cells were analyzed as in (A). (D) Smad4-negative MDA-MB-468 cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of p3TP-Lux, and 1.0 μg of the expression vector of RBPMS in both the absence and presence of the expression plasmid for Smad4. (E) 293T cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of lac-Luc, 50 ng of the expression plasmid for lac-tagged Smad2, Smad3 or Smad4, and 1 μg of the expression vector for FLAG-tagged RBPMS.

The observations that RBPMS enhanced the p3TP-Lux reporter activity in the absence of exogenous TGF-β raise the possibility that overexpression of RBPMS might confer ligand-independent activation of the reporter or RBPMS-induced increase in the reporter activity in the absence of exogenous TGF-β could be due to an autocrine TGF-β response. To test this possibility, transfected cells were treated with a TGF-β neutralizing antibody. The antibody treatment of 293T cells completely abolished the reporter activation by RBPMS (Figure 4C). These results suggest that TGF-β is required for RBPMS-induced increase in the reporter activity and the RBPMS activity in the absence of exogenous TGF-β is due to autocrine TGF-β.

To investigate whether Smad4, a central mediator in TGF-β signaling, is required for the effect of RBPMS on the 3TP-Lux reporter gene transcription, human breast cancer MDA-MB-468 cells, which lack endogenous Smad4 (33), were cotransfected with the 3TP-Lux reporter and RBPMS, together with or without Smad4. Cotransfection of RBPMS and the 3TP-Lux reporter in MDA-MB-468 cells did not increase the p3TP-Lux reporter transcription, whereas cotransfection of these genes with human Smad4 expression vector led to activation of the p3TP-Lux (Figure 4D). Therefore, RBPMS acts through Smad4 to increase p3TP-Lux reporter transcription.

Since RBPMS can directly interact with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4, the possibility that RBPMS may directly regulate Smad transcriptional activity was tested. A lac repressor–lac operator recognition system was used (22), in which Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 were fused to the lac repressor. As previously reported (16), Smad2 and Smad3 had intrinsic transcriptional activity, whereas Smad4 did not (Figure 4E). Expression of RBPMS enhanced the transcriptional activity of Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4, demonstrating the coactivator function of RBPMS for these Smad proteins.

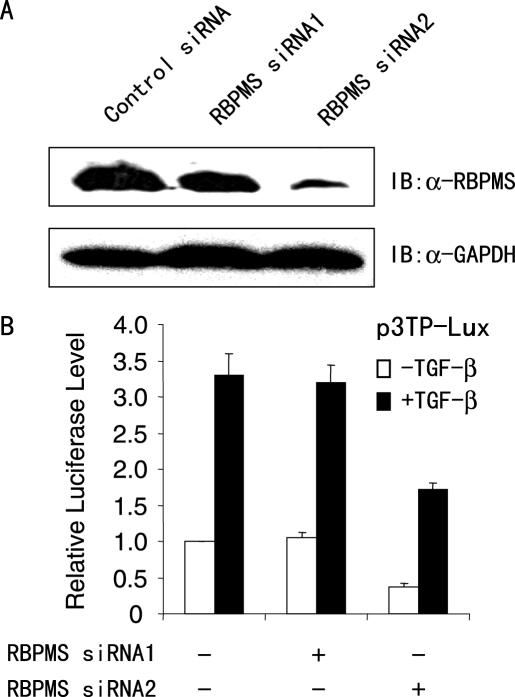

Knockdown of endogenous RBPMS suppressed TGF-β/Smad-mediated transactivation

To investigate the role of endogenous RBPMS in activation of the p3TP-Lux reporter, 293T cells were transfected with vector-based RBPMS siRNAs or universal scramble siRNA (control). As shown in Figure 5A, RBPMS siRNA2 effectively inhibited the expression of RBPMS protein, whereas RBPMS siRNA1 and universal scramble siRNA had little or no effect. As another control, the RBPMS siRNAs did not reduce the expression of Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 proteins (data not shown). Suppression of the normal expression of RBPMS in 293T cells by the specific RBPMS siRNA2 significantly decreased the reporter activity (Figure 5B). Consistent with the results of the overexpression experiments, the magnitude of the reporter repression in the absence of TGF-β1 was greater than that in the presence of TGF-β1. Taken together, these results suggest that RBPMS can enhance TGF-β responsive reporter activity both in a ligand-indpendent and in a ligand-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of endogenous RBPMS reduces TGF-β/Smad-mediated transcriptional activity. (A) Western blotting with indicated antibodies showing the specific knockdown effect of the two RBPMS siRNAs on the endogeous RBPMS protein level. 293T cells were transfected with expression vectors for two different RBPMS siRNAs or scramble siRNA (control) plasmid. Forty-eight hours after transfection, whole-cell extracts were prepared and probed with anti-RBPMS or GAPDH. (B) Luciferase reporter assay in the control and RBPMS knockdown cells using the p3TP-Lux reporter. 293T cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of p3TP-Lux, and 1.0 μg of RBPMS siRNA as indicated.

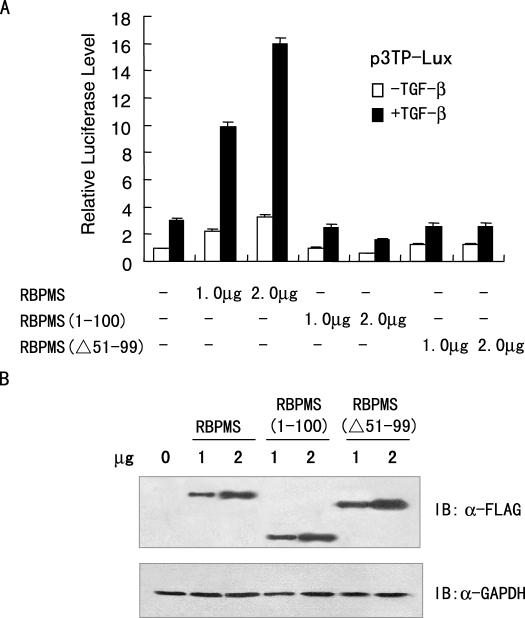

Both the N-terminus and the C-terminus are required for full function of RBPMS

To map the regions required for RBPMS transactivation function, we generated two RBPMS deletion mutants in which the N-terminal partial RRM and the C-terminus without RRM were selectively deleted. RBPMS were compared with the two RBPMS deletion mutants, FLAG-tagged RBPMS(1–100) and FLAG-tagged RBPMS(Δ51–99), in a transient transfection assay. As shown in Figure 6A, while RBPMS stimulated TGF-β/Smad-regulated transcription, RBPMS(1–100) that contains the interacting region of RBPMS on Smad4 repressed the RBPMS activity in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that RBPMS(1–100) has a dominant-negative effect and that the C-terminus is required for RBPMS activation possibly through recruitment of factors important for transcriptional regulation. Deletion of the N-terminal partial RRM (FLAG-tagged RBPMS(Δ51–99)) almost fully abolished the activity of RBPMS, suggesting that the RRM is important for RBPMS transactivation in addition to the C-terminus. Notably, FLAG-tagged RBPMS, RBPMS(1–100) and RBPMS(Δ51–99) were expressed at comparable levels (Figure 6B). Although we also tried to delete the entire RRM, this mutant [RBPMS(101–220)] was not expressed (data not shown). Taken together, the above data suggest that both the RRM and the C-terminus are required for full function of RBPMS.

Figure 6.

Full-length RBPMS is required for stimulation of TGF-β/Smad-mediated transactivation. (A) Luciferase reporter assay with the RBPMS deletion mutants. 293T cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of p3TP-Lux and increasing amounts of the expression plasmid for FLAG-tagged RBPMS, RBPMS(1–100) or RBPMS(Δ51–99) as indicated. (B) Western blotting showing expression levels of FLAG-tagged RBPMS, RBPMS(1–100) or RBPMS(Δ51–99) with antibody against FLAG or GAPDH. 293T cells were transfected in the presence of TGF-β as in (A).

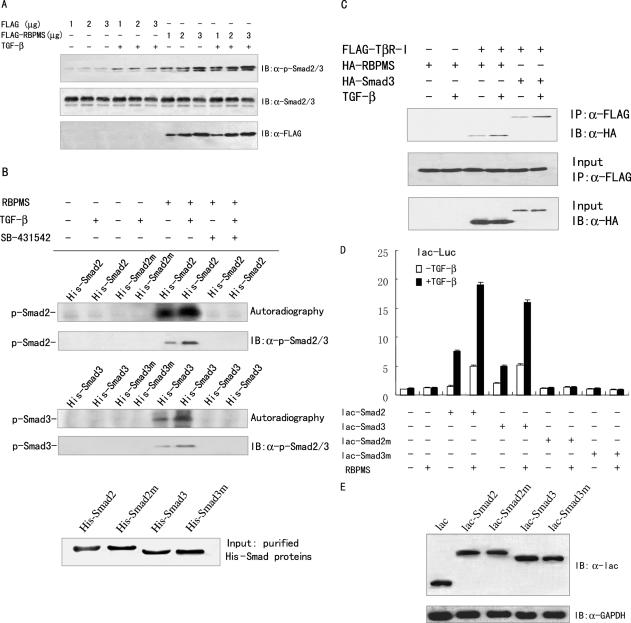

RBPMS increases phosphorylation of C-terminal SSXS regions in Smad2 and Smad3

Phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 on their C-terminal SSXS motif has been shown to be required for TGF-β/Smad-mediated transcriptional activation (34–36). To elucidate the mechanism for the enhanced transcriptional activity of the Smad proteins by RBPMS, the effect of RBPMS on the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 at the C-terminal regions was examined. 293T cells were transfected with expression vector for FLAG-tagged RBPMS or its empty vector. As shown in Figure 7A, the levels of Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation on the C-terminal SSXS motif were increased in 293T cells transfected with RBPMS, as measured by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-Smad2/3. RBPMS increased the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 7.

C-terminal phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 correlates with RBP coactivation of Smad2 and Smad3. (A) RBPMS increased phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 at the C-terminus. Serum-starved 293T cells were transfected with increasing amounts of the RBPMS expression vector or its empty vector as indicated. Cells were treated with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 1 h. Cell lysates were prepared and probed with anti-phospho-Smad2/3 (Ser 423/425) (Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-Smad2/3 (Upstate), or anti-FLAG. (B) In vitro phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 at the C-terminus by RBPMS immunoprecipitate. 293T cells were transfected with 3 μg of the RBPMS expression vector or its empty vector, and treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1, in combination with 10 μM TβR-I inhibitor SB-431542. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG. In vitro kinase assays were performed using His-Smad2, His-Smad3 and their C-terminal mutants (His-Smad2m and His-Smad3m) as substrates. The phosphorylated states of Smad2 and Smad3 were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography or immunoblotting with anti-phospho-Smad2/3 as indicated. The bottom panel indicates SDS–PAGE analysis of His-Smad2, His-Smad3 and their mutant proteins purified from bacteria. (C) Interaction of RBPMS with TβR-I in vivo. FLAG-tagged TβR-I and HA-tagged RBPMS were cotransfected into 293T cells in the presence or absence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-FLAG, and the precipitates were then immunoblotted (IB) with anti-HA antibody. (D) RBPMS failed to increase the transcriptional activity of Smad2 and Smad3 that lack the C-terminal phosphorylation sites. 293T cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of lac-Luc, 50 ng of the expression plasmid for lac-tagged Smad2, Smad3 or their C-terminal mutants (lac-Smad2m and lac-Smad3m), and 1 μg of the expression vector for FLAG-tagged RBPMS, with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. (E) Western blotting with indicated antibodies showing expression levels of lac-tagged Smad2, Smad3 or their C-terminal mutants. 293T cells were transfected in the presence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 as in (D).

To further confirm the phosphorylation stimulated by RBPMS, in vitro kinase assay was performed. Immunoprecipitate of the cell extract from 293T cells transfected with FLAG-tagged RBPMS or empty vector using anti-FLAG was mixed with His-Smad2 or His-Smad3 purified from bacteria. As another control, mutants of His-Smad2 and His-Smad3 were used in which the C-terminal Ser 423 and 425 in Smad3 and Ser 465 and Ser 467 in Smad2 were changed to alanine. As shown in Figure 7B, both in the absence and in the presence of exogenous TGF-β, RBPMS immunoprecipitate could phosphorylate His-Smad2 and His-Smad3, but not the mutants, as evidenced by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography or immunoblotting with the anti-phospho-Smad2/3. The RBPMS-induced phosphorylation of His-Smad2 and His-Smad3 without exogenous TGF-β1 may be due to an autocrine TGF-β response in 293T cells because treatment with the TβR-I inhibitor SB-431542 completely abolished the in vitro phosphorylation activity of the RBPMS immunoprecipitate.

The observations that the phosphorylation activity of the RBPMS immunoprecipitate depends on TβR-I raise the possibility that RBPMS may physically interact with TβR-I. To test this possibility, FLAG-tagged TβR-I and HA-tagged RBPMS were cotransfected into 293T cells, and co-immunoprecipitation was performed. As shown in Figure 7C, RBPMS specifically interacted with TβR-I, and TGF-β enhanced the interaction of RBPMS with TβR-I. As a positive control, Smad3 associated with TβR-I. These data suggest that RBPMS immunoprecipitate specifically phosphorylates the C-terminal SSXS regions of Smad2 and Smad3 possibly through recruitment of TβR-I.

To establish a link between the C-terminal phosphorylation and RBPMS coactivation of Smad2 and Smad3, 293T cells were cotransfected with the lac-Luc reporter and RBPMS, together with lac-tagged Smad2 and Smad3, or their mutants in which the C-terminal Ser 423 and 425 in Smad3 and Ser 465 and Ser 467 in Smad2 were changed to alanine. As expected, RBPMS increased Smad2- and Smad3-mediated transcriptional activity (Figure 7D). The lac-Smad2 and lac-Smad3 mutants lost their intrinsic transcriptional activity. Importantly, RBPMS failed to enhance the transcriptional activity of Smad2 and Smad3 that lack the C-terminal phosphorylation sites. It should be noted that lac-tagged Smad2 and Smad3 and their mutants were expressed at comparable levels (Figure 7E). Thus, the C-terminal phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 strongly correlates with RBPMS coactivation function.

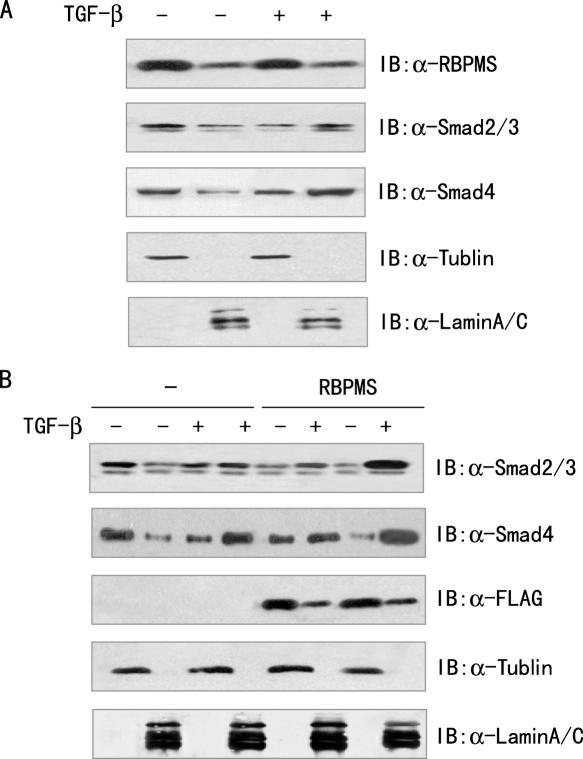

RBPMS promotes the nuclear accumulation of Smad proteins

Since RBPMS is a protein with unknown function, the localization of RBPMS protein was determined by subcellular fractionation, followed by immunoblotting with the anti-RBPMS. 293T cells were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. As shown in Figure 8A, although RBPMS was predominantly cytoplasmic, a significant proportion of RBPMS was detected in the nuclear fraction of 293T cells. TGF-β1 did not appear to affect the subcellular localization of the RBPMS protein.

Figure 8.

RBPMS promotes the nuclear accumulation of Smad proteins. (A) Subcellular localization of RBPMS. Serum-starved 293T cells were treated with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. The cells were then fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. The lysates were probed with the anti-RBPMS. Lamin A/C and α-tubulin were used as the nuclear and cytoplasmic marker, respectively. (B) RBPMS-induced nuclear accumulation of Smad proteins. Serum-starved 293T cells were transfected with 3 μg of the FLAG-tagged RBPMS expression vector or its empty vector, and treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. The cells were fractionated as in (A). The lysates were detected with anti-FLAG, anti-Smad2/3 or anti-Smad4.

As RBPMS can increase the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 on their C-terminal SSXS motif, which has been shown to be critical for translocation of these Smad proteins from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (37), we hypothesized that RBPMS could promote the nuclear accumulation of the Smad proteins. To test this possibility, we transfected FLAG-tagged RBPMS or its empty vector into 293T cells. In the absence of exogenous TGF-β1, Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 were predominantly localized in the cytoplasm of the 293T cells, whereas treatment with TGF-β1 increased the proportion of these Smad proteins in the nuclear fraction (Figure 8B). Intriguingly, the expression of RBPMS increased the proportion of the Smad proteins in the nuclear fraction. These data suggest that RBPMS promotes the nuclear accumulation of Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4.

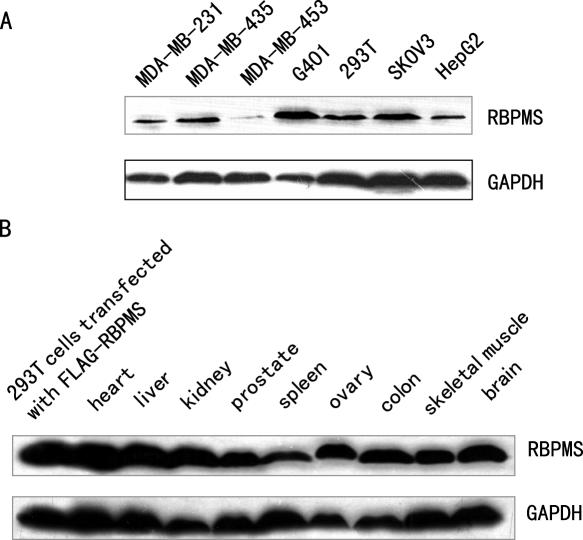

Ubiquitous expression of RBPMS protein

Although RBPMS has been shown to be expressed at mRNA level, the expression of RBPMS protein remains to be determined (24–28). For this, western blot analysis was performed in various human cell lines as well as in rat tissues with the anti-RBPMS antibody. As shown in Figure 9A, a specific band of RBPMS protein was detected in all of the human cell lines tested, including breast cancer (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435 and MDA-MB-453), ovary cancer (SKOV3), liver cancer (HepG2) and kidney cells (G401 and 293T), although with different levels. The specific band was also present in all the rat tissues tested including heart, liver, kidney, prostate, spleen, ovary, colon, skeletal muscle and brain (Figure 9B). The wide distribution of RBPMS suggests a potential function of RBPMS in modulation of the general transcriptional machinery.

Figure 9.

Expression of RBPMS in different human cell lines as well as rat tissues. RBPMS expression was detected by western blot with anti-RBPMS using proteins from indicated human cell lines (A) as well as rat tissues (B). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that, like hermes, the Xenopus homolog of RBPMS, RBPMS can interact with RNA in vivo. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence for an RNA-binding protein playing a role in the regulation of Smad-mediated transcriptional activity. Recently, many cofactors, including coactivators and corepressors, have been identified to interact with Smad proteins and modulate TGF-β/Smad-mediated transcriptional activation. Most of the identified cofactors are corepressors, such as Ski (18,19), SnoN (20) and SNIP1 (21). Only a few coactivators, such as CBP/p300 (15) and P/CAF (16), have been shown to interact with Smad proteins and enhance TGF-β/Smad-induced transcription. In the present study, we provide evidence of physical and functional interaction between the member of the RNA-binding protein family RBPMS and Smad proteins. The physical interaction has been validated by a number of in vitro and in vivo experiments, including yeast two-hybrid, in vitro GST pull-down, and in vivo co-immunoprecipitation. Moreover, RBPMS directly interacts with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4. Importantly, we further show that RBPMS functionally enhances Smad-mediated transcriptional activity. Since RBPMS is ubiquitously expressed in different cells in culture as well as in various tissues, our data suggest that RBPMS may be a novel coactivatior of Smad proteins and may play roles in multiple tissues.

Although the function of human RBPMS remains unknown, hermes, the Xenopus homolog of RBPMS, has been shown to inhibit heart development in the developing Xenopus embryo (25,26). Hermes is involved in the regulation of mature transcripts required for myocardial differentiation. Like other RNA-binding proteins, hermes can form a multiprotein complex and bind to mature RNA transcripts. Although RNA-binding proteins are generally considered to participate in posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression (38,39), our study has identified a new role of RBPMS in gene transcription. The fact that the RNA-binding domain of RBPMS is required for RBPMS coactivation of Smad transcriptional activity but RNA is not required for the interaction of RBPMS with Smad proteins suggests that RBPMS are involved in two separate events, transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression, and the binding of RBPMS to RNA and Smad proteins might be mutually exclusive. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that RBPMS may also modulate Smad-mediated transactivation function through posttranscriptional regulation. This hypothesis is supported by a recent finding that regulators that interact with steroid hormone receptors, which act as ligand-dependent transcription factors, served as both coactivators and splicing factors (40). Taken together, our data suggest that the RRM of RBPMS may function not only as an RNA-binding domain that necessitates RNA-binding but also as a protein–protein interaction domain that may function independently of a RNA cofactor.

Recently, only a few RNA-binding proteins have been found to play a role in gene transcription (41–43). For example, thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), which belong to the nuclear receptor superfamily, regulate target gene transcription by interacting with DNA response elements and coregulatory proteins. However, TRs also are single-stranded RNA binding proteins, and the RNA-binding domain of TRs is important for coactivation by SRA, an RNA coactivator for TRs as well as steroid receptors (41). PRIP-interacting protein with methyltransferase domain (PIMT) can bind to RNA but not single- and double-stranded DNA. PIMT increases the transcriptional activity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and retinoid-X-receptor α (RXRα), which is further stimulated by overexpression of PRIP, a coactivator for PPARγ (42). Although whether coactivator activator (CoAA) binds RNA remains to be investigated, CoAA contains two highly conserved RRMs commonly found in ribonucleoproteins. CoAA potently enhances nuclear receptor-mediated transcription and acts synergistically with TRBP (TR-binding protein), which interacts with CoAA. Both the two RRMs and the TRBP-interacting domain are required for full function of CoAA (43). Our observation that the RRM alone was inactive or inhibitory in RBPMS coactivation of Smad proteins and that deletion of the partial RRM almost completely abolishes the RBPMS activity suggests that RBPMS acts similar to CoAA. Combined with the others, our study indicates that RNA-binding proteins play a role in transcriptional regulation.

TGF-β was shown to exert transcriptional responses through Smad2 and Smad3, which are direct TGF-β receptor substrates. Receptor-mediated phosphorylation of these Smads on the C-terminal SSXS motif induces their association with the common partner Smad4, followed by translocation into the nucleus, where these complexes regulate transcription of target genes. Although receptor phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 on the C-terminal SSXS motif is critical for activation of TGF-β signaling, a possible regulatory role for several other phosphorylation sites, especially in the linker region, has been described (44–49). The phosphorylation could be mediated by members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, which includes the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) pathway (44) and two stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) pathways: the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the p38 pathway (45–49), and of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) family, which include CDK2 and CDK4 (49). Oncogenically activated Ras can phosphorylate R-Smads, including Smad2 and Smad3, at Ser/Thr-Pro (S/TP) sites in the linker region through ERK kinases, and suppress Smad-dependent transcription. JNK and/or p38 MAPK activated on TGF-β treatment can directly phosphorylate R-Smads at linker regions. CDK2 and CDK4 phosphorylate Smad3 at Thr8 in the MH1 domain and Thr178, Ser212 at sites in the linker region and this, in turn, inhibits its transcriptional activity. Our study showed that RBPMS can facilitate R-Smads phosphorylation on the C-terminal SSXS motif and thus stimulate Smad-mediated transcription. However, the protein complex involved in this process remains to be determined. Since RBPMS immunoprecipitate specifically phosphorylates Smad2 and Smad3 on the C-terminal SSXS motif but not the linker region (Figure 7 and data not shown) and RBPMS enhances the transcriptional activity of Smad proteins, it is unlikely that the previously reported kinases, such as ERK, JNK, p38 and CDK2/4, are responsible for RBPMS-stimulated phosphorylation. Although RBPMS increases Smad transcriptional activity in 293T cells even in the absence of TGF-β, the treatment of a TGF-β neutralizing antibody completely abolishes the RBPMS coactivation function, suggesting that 293T cells express endogenous TGF-β sufficient and required for RBPMS activation. The inhibitor of the TGF-β receptor I, TβR-I, completely abrogates the in vitro phosphorylation activity of the RBPMS immunoprecipitate, further indicating that TβR-I, which is activated by TGF-β, is required for the RBPMS activity. Since RBPMS can interact both with TβR-I and with Smad proteins in vivo, and TβR-I has been shown to transiently associate with and phosphorylate Smad2 and Smad3, it should be TβR-I in the RBPMS immunoprecipitate that phosphorylates Smad2 and Smad3. The fact that RBPMS does not associate with Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylated on their C-terminal SSXS motif further suggests that TβR-I, RBPMS and unphosphorylated Smad2/3 may form a complex and phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 by the TβRI complex results in dissociation of Smad2 and Smad3 from the complex. RBPMS may act as an important factor for the TβR-I-induced phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 because RBPMS increases such phosphorylation in vivo. Phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 has been shown to be required for their accumulation in the nucleus where the proteins can function as transcriptional activators. Consistent with this, RBPMS promotes the nuclear accumulation of Smad2 and Smad3, and potentiates Smad-mediated transcriptional activity. Thus, RBPMS increases TGF-β signaling possibly by increasing Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation at the C-terminus, and promoting the nuclear accumulation of the Smad complex. It will be interesting to determine the precise mechanism by which RBPMS stimulates TGF-β/Smad-mediated transactivation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Key Technologies R&D Program (2002BA711A02-5) and National Natural Science Foundation (30530320, 30370738 and 30428012). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Key Technologies R&D Program.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Itoh S., Itoh F., Goumans M.J., Ten Dijke P. Signaling of transforming growth factor-β family members through Smad proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:6954–6967. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moustakas A., Souchelnytskyi S., Heldin C.H. Smad regulation in TGF-β signal transduction. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:4359–4369. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ten Dijke P., Goumans M.J., Itoh F., Itoh S. Regulation of cell proliferation by Smad proteins. J. Cell Physiol. 2002;191:1–16. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massague J., Wotton D. Transcriptional control by the TGF-β/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Y., Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu F., Hata A., Baker J.C., Doody J., Carcamo J., Harland R.M., Massague J. A human Mad protein acting as a BMP-regulated transcriptional activator. Nature. 1996;381:620–623. doi: 10.1038/381620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyaki M., Kuroki T. Role of Smad4 (DPC4) inactivation in human cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;306:799–804. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y. Structural insights on Smad function in TGF-β signaling. Bioessays. 2001;23:223–232. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200103)23:3<223::AID-BIES1032>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Feng X.H., Derynck R. Smad3 and Smad4 cooperate with c-Jun/c-Fos to mediate TGF-β-induced transcription. Nature. 1998;394:909–913. doi: 10.1038/29814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams T.M., Williams M.E., Heaton J.H., Gelehrter T.D., Innis J.W. Group 13 HOX proteins interact with the MH2 domain of R-Smads and modulate Smad transcriptional activation functions independent of HOX DNA-binding capability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4475–4484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinn Z.A., Yang C.C., Wrana J.L., McDermott J.C. Smad proteins function as co-modulators for MEF2 transcriptional regulatory proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:732–742. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.3.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati N.T., Datto M.B., Frederick J.P., Shen X., Wong C., Rougier-Chapman E.M., Wang X.F. Smads bind directly to the Jun family of AP-1 transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4844–4849. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Pascual F., Redondo-Horcajo M., Lamas S. Functional cooperation between Smad proteins and activator protein-1 regulates transforming growth factor-β-mediated induction of endothelin-1 expression. Circ. Res. 2003;92:1288–1295. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000078491.79697.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chipuk J.E., Cornelius S.C., Pultz N.J., Jorgensen J.S., Bonham M.J., Kim S.J., Danielpour D. The androgen receptor represses transforming growth factor-β signaling through interaction with Smad3. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:1240–1248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng X.H., Zhang Y., Wu R.Y., Derynck R. The tumor suppressor Smad4/DPC4 and transcriptional adaptor CBP/p300 are coactivators for smad3 in TGF-β-induced transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2153–2163. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh S., Ericsson J., Nishikawa J.I., Heldin C.H., Ten Dijke P. The transcriptional co-activator P/CAF potentiates TGF-β/Smad signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4291–4298. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wotton D., Lo R.S., Lee S., Massague J. A Smad transcriptional corepressor. Cell. 1999;97:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo K., Stroschein S.L., Wang W., Chen D., Martens E., Zhou S., Zhou Q. The Ski oncoprotein interacts with the Smad proteins to repress TGFβ signaling. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2196–2206. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu W., Angelis K., Danielpour D., Haddad M.M., Bischof O., Campisi J., Stavnezer E., Medrano E.E. Ski acts as a co-repressor with Smad2 and Smad3 to regulate the response to type β transforming growth factor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5924–5929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090097797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroschein S.L., Wang W., Zhou S., Zhou Q., Luo K. Negative feedback regulation of TGF-β signaling by the SnoN oncoprotein. Science. 1999;286:771–774. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim R.H., Wang D., Tsang M., Martin J., Huff C., de Caestecker M.P., Parks W.T., Meng X., Lechleider R.J., Wang T., Roberts A.B. A novel smad nuclear interacting protein, SNIP1, suppresses p300-dependent TGF-β signal transduction. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1605–1616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye Q., Hu Y.F., Zhong H., Nye A.C., Belmont A.S., Li R. BRCA1-induced large-scale chromatin unfolding and allele-specific effects of cancer-predisposing mutations. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:911–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J., Fang Y., Ding L., Zhu J., Lu Q., Huang C., Yang X., Ye Q. Regulation of large-scale chromatin unfolding by Smad4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;315:330–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimamoto A., Kitao S., Ichikawa K., Suzuki N., Yamabe Y., Imamura O., Tokutake Y., Satoh M., Matsumoto T., Kuromitsu J., et al. A unique human gene that spans over 230 kb in the human chromosome 8p11-12 and codes multiple family proteins sharing RNA-binding motifs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:10913–10917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerber W.V., Yatskievych T.A., Antin P.B., Correia K.M., Conlon R.A., Krieg P.A. The RNA-binding protein gene, hermes, is expressed at high levels in the developing heart. Mech. Dev. 1999;80:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerber W.V., Vokes S.A., Zearfoss N.R., Krieg P.A. A role for the RNA-binding protein, hermes, in the regulation of heart development. Dev. Biol. 2002;247:116–126. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zearfoss N.R., Chan A.P., Wu C.F., Kloc M., Etkin L.D. Hermes is a localized factor regulating cleavage of vegetal blastomeres in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 2004;267:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilmore H.P., McClive P.J., Smith C.A., Sinclair A.H. Expression profile of the RNA-binding protein gene hermes during chicken embryonic development. Dev. Dyn. 2005;233:1045–1051. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carcamo J., Zentella A., Massague J. Disruption of transforming growth factor β signaling by a mutation that prevents transphosphorylation within the receptor complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:1573–1581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkes M.C., Murphy S.J., Garamszegi N., Leof E.B. Cell-type-specific activation of PAK2 by transforming growth factor β independent of Smad2 and Smad3. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:8878–8889. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8878-8889.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding L., Yan J., Zhu J., Zhong H., Lu Q., Wang Z., Huang C., Ye Q. Ligand-independent activation of estrogen receptor alpha by XBP-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5266–5274. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babic I., Jakymiw A., Fujita D.J. The RNA binding protein Sam68 is acetylated in tumor cell lines, and its acetylation correlates with enhanced RNA binding activity. Oncogene. 2004;23:3781–3789. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Winter J.P., Roelen B.A., ten Dijke P., van der Burg B., van den Eijnden-van Raaij A.J. DPC4 (SMAD4) mediates transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) induced growth inhibition and transcriptional response in breast tumour cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:1891–1899. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng X.H., Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in TGF-β signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Javelaud D., Mauviel A. Crosstalk mechanisms between the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways and Smad signaling downstream of TGF-β: implications for carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:5742–5750. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ten Dijke P., Hill C.S. New insights into TGF-β-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macias-Silva M., Abdollah S., Hoodless P.A., Pirone R., Attisano L., Wrana J.L. MADR2 is a substrate of the TGFβ receptor and its phosphorylation is required for nuclear accumulation and signaling. Cell. 1996;87:1215–1224. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clerch L.B. Post-transcriptional regulation of lung antioxidant enzyme gene expression. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000;899:103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim Y.K., Furic L., Desgroseillers L., Maquat L.E. Mammalian Staufen1 recruits Upf1 to specific mRNA 3′UTRs so as to elicit mRNA decay. Cell. 2005;120:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Auboeuf D., Honig A., Berge S.M., O'Malley B.W. Coordinate regulation of transcription and splicing by steroid receptor coregulators. Science. 2002;298:416–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1073734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu B., Koenig R.J. An RNA-binding domain in the thyroid hormone receptor enhances transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33051–33056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Y., Qi C., Cao W.Q., Yeldandi A.V., Rao M.S., Reddy J.K. Cloning and characterization of PIMT, a protein with a methyltransferase domain, which interacts with and enhances nuclear receptor coactivator PRIP function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10380–10385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181347498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwasaki T., Chin W.W., Ko L. Identification and characterization of RRM-containing coactivator activator (CoAA) as TRBP-interacting protein, and its splice variant as a coactivator modulator (CoAM) J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33375–33383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kretzschmar M., Doody J., Timokhina I., Massague J. A mechanism of repression of TGF-β/Smad signaling by oncogenic Ras. Genes Dev. 1999;13:804–816. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamagata H., Matsuzaki K., Mori S., Yoshida K., Tahashi Y., Furukawa F., Sekimoto G., Watanabe T., Uemura Y., Sakaida N., Yoshioka K., Kamiyama Y., Seki T., Okazaki K. Acceleration of Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation via c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase during human colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mori S., Matsuzaki K., Yoshida K., Furukawa F., Tahashi Y., Yamagata H., Sekimoto G., Seki T., Matsui H., Nishizawa M., et al. TGF-β and HGF transmit the signals through JNK-dependent Smad2/3 phosphorylation at the linker regions. Oncogene. 2004;23:7416–7429. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayes S.A., Huang X., Kambhampati S., Platanias L.C., Bergan R.C. p38 MAP kinase modulates Smad-dependent changes in human prostate cell adhesion. Oncogene. 2003;22:4841–4850. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamaraju A.K., Roberts A.B. Role of Rho/ROCK and p38 MAP kinase pathways in transforming growth factor-β-mediated Smad-dependent growth inhibition of human breast carcinoma cells in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:1024–1036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuura I., Denissova N.G., Wang G., He D., Long J., Liu F. Cyclin-dependent kinases regulate the antiproliferative function of Smads. Nature. 2004;430:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature02650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]