Abstract

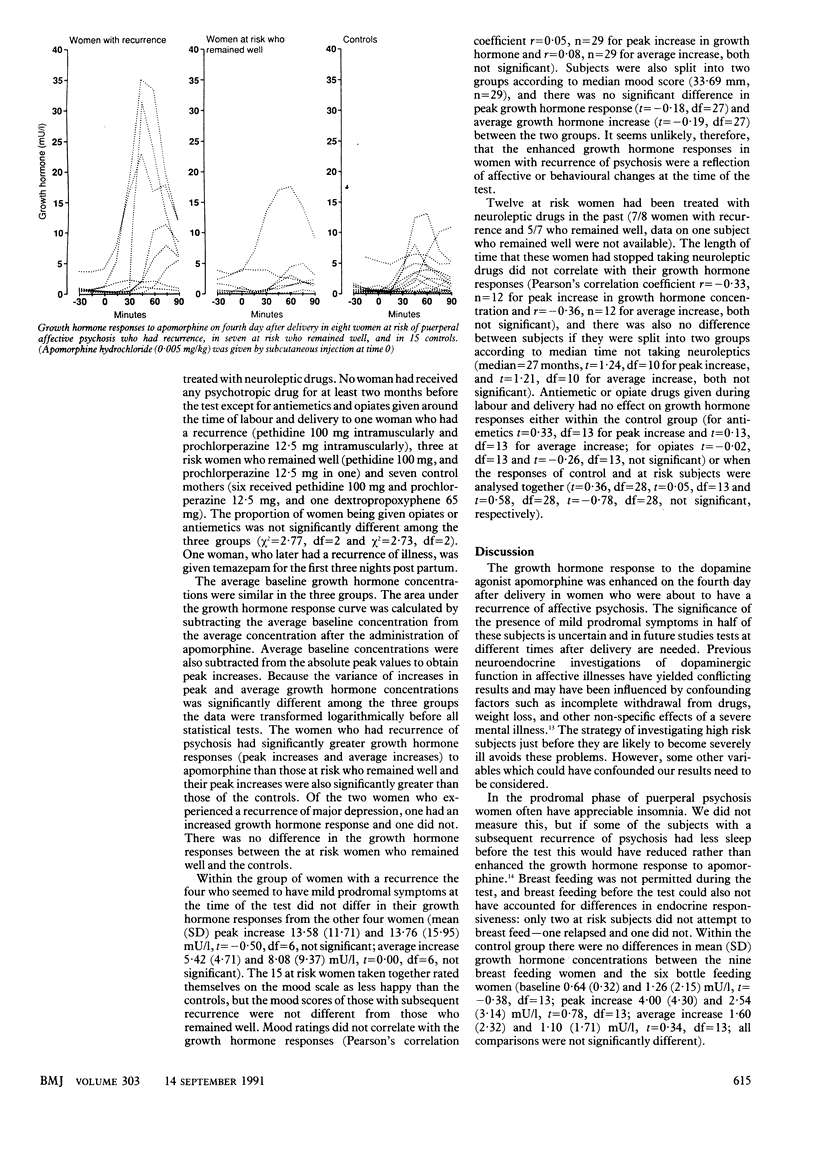

OBJECTIVE--To test the hypothesis that affective psychosis after childbirth is associated with an altered sensitivity to dopaminergic stimulation. DESIGN--Prospective study of pregnant women at high risk of developing an affective psychosis after childbirth. Clinical assessments in pregnancy and after delivery were made by using a semistructured interview (schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia) and psychiatric illnesses were categorised according to operational criteria (research diagnostic criteria). SETTING--Obstetric and psychiatric departments in and around Greater London. SUBJECTS--29 pregnant women with a history of bipolar or schizoaffective psychosis and 47 control pregnant women. Of these, 16 from each group participated in a growth hormone challenge test and the results for 15 women in each group were analysed. INTERVENTIONS--On the fourth day postpartum women participating in the hormone challenge test were given a subcutaneous injection of a small dose (0.005 mg/kg) of the dopamine agonist apomorphine. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Growth hormone secretion in response to apomorphine as an index of the functional state of hypothalamic dopamine receptors. RESULTS--Eight of the 15 women at risk of psychosis subsequently had a recurrence of illness (five bipolar, one schizomanic, and two major depressive illnesses); these women had significantly greater growth hormone responses to apomorphine than the seven at risk women who remained well and the 15 controls, and there were no significant differences between groups in average baseline growth hormone concentrations. The mean (SD) concentrations for women with recurrence, women at risk who remained well, and control women respectively were: average baseline concentrations 1.06 (1.14), 1.44 (1.39), and 0.90 (1.34) mU/l; peak increase in concentrations 13.68 (12.95), 3.46 (4.68), and 3.40 (3.83) mU/l (between group difference p less than 0.05); average increase in concentrations 6.74 (7.01), 1.78 (3.39), and 1.40 (2.05) mU/l (p less than 0.05). CONCLUSIONS--The onset of affective psychosis after childbirth was associated with increased sensitivity of dopamine receptors in the hypothalamus and possibly elsewhere in the brain. Such changes may be triggered by the sharp fall in circulating oestrogen concentrations after delivery.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blum M., McEwen B. S., Roberts J. L. Transcriptional analysis of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons of the rat arcuate nucleus after estrogen treatment. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jan 15;262(2):817–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström T., Carstensen H., Södergard R. Concentration of estradiol, testosterone and progesterone in cerebrospinal fluid compared to plasma unbound and total concentrations. J Steroid Biochem. 1976 Jun-Jul;7(6-7):469–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(76)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkley S. A. Neuroendocrine tests of monoamine function in man: a review of basic theory and its application to the study of depressive illness. Psychol Med. 1980 Feb;10(1):35–53. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700039593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson J. C. The neuroendocrinology of mania. J Affect Disord. 1985 May-Jun;8(3):233–241. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corn T. H., Hale A. S., Thompson C., Bridges P. K., Checkley S. A. A comparison of the growth hormone responses to clonidine and apomorphine in the same patients with endogenous depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1984 Jun;144:636–639. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.6.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C., Williams R. J., Brockington I. F. Is puerperal psychosis the same as bipolar manic-depressive disorder? A family study. Psychol Med. 1989 Aug;19(3):637–647. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700024235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest K. T., Riegle G. D., Moore K. E. Long-term treatment with estradiol induces reversible alterations in tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons: a decreased responsiveness to prolactin. Neuroendocrinology. 1984 Sep;39(3):193–200. doi: 10.1159/000123979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J., Spitzer R. L. A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978 Jul;35(7):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettigi P., Lal S., Martin J. B., Friesen H. G. Effectof sex, oral contraceptives, and glucose loading on apomorphine-induced growth hormone secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1975 Jun;40(6):1094–1098. doi: 10.1210/jcem-40-6-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelato M. C., Pescovitz O. H., Cassorla F., Loriaux D. L., Merriam G. R. Dose-response relationships for the effects of growth hormone-releasing factor-(1-44)-NH2 in young adult men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984 Aug;59(2):197–201. doi: 10.1210/jcem-59-2-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell R. E., Chalmers J. C., Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 May;150:662–673. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Isaacs S., Meltzer E. Recurrent post-partum psychosis. A model for prospective clinical investigation. Br J Psychiatry. 1983 Jun;142:618–620. doi: 10.1192/bjp.142.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal S., Thavundayil J., Nair N. P., Etienne P., Rastogi R., Schwartz G., Pulman J., Guyda H. Effect of sleep deprivation on dopamine receptor function in normal subjects. J Neural Transm. 1981;50(1):39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF01254912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer H. Y. Relevance of dopamine autoreceptors for psychiatry: preclinical and clinical studies. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6(3):456–475. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. J., Grossman A., Davies P. S., Savage M. O., Besser G. M. Stilboestrol pretreatment of children with short stature does not affect the growth hormone response to growth hormone-releasing hormone. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1987 Aug;27(2):155–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1987.tb01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R. L., Endicott J., Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978 Jun;35(6):773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hartesveldt C., Joyce J. N. Effects of estrogen on the basal ganglia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1986 Spring;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(86)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]