Abstract

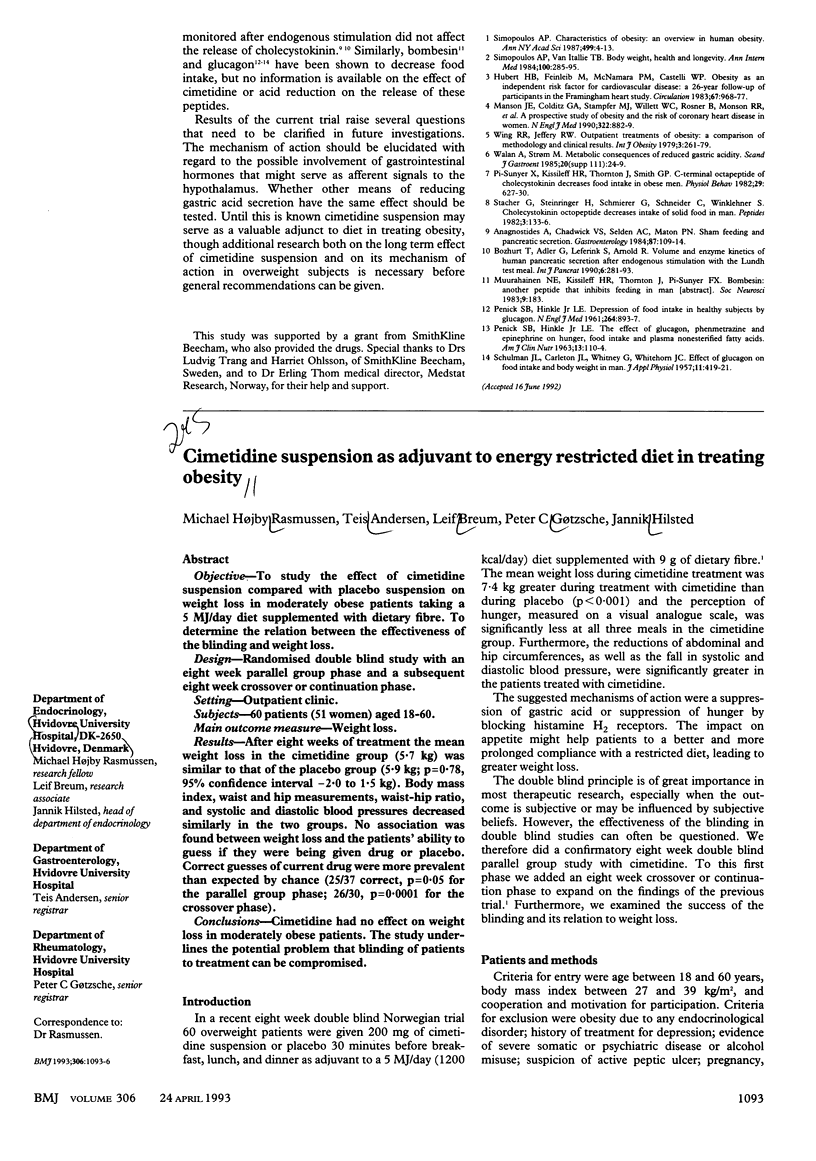

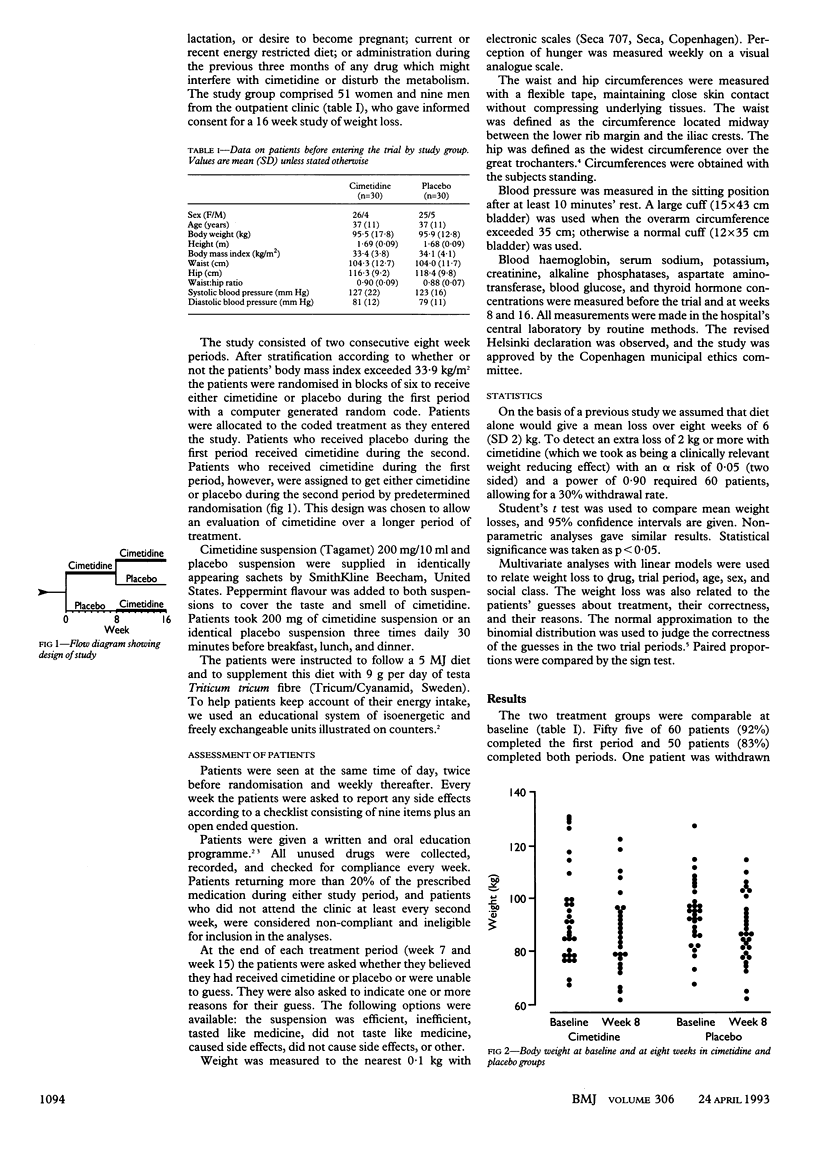

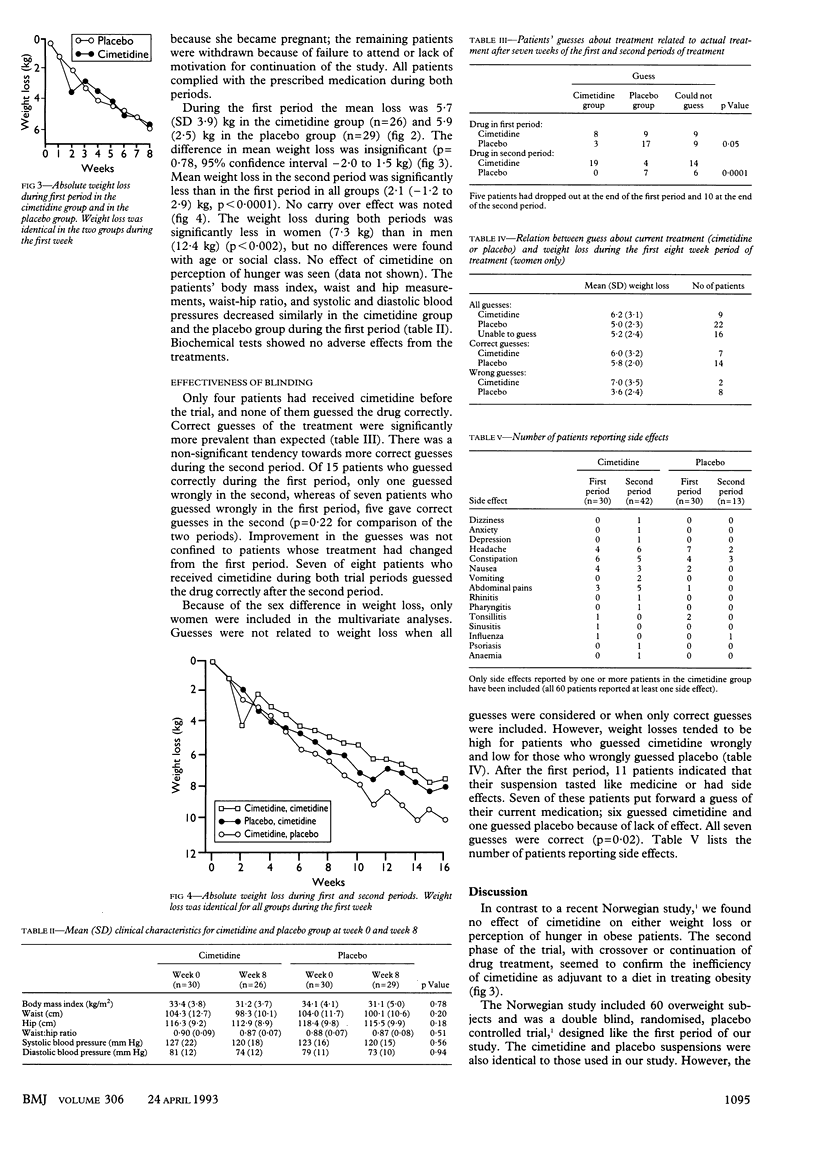

OBJECTIVE--To study the effect of cimetidine suspension compared with placebo suspension on weight loss in moderately obese patients taking a 5 MJ/day diet supplemented with dietary fibre. To determine the relation between the effectiveness of the blinding and weight loss. DESIGN--Randomised double blind study with an eight week parallel group phase and a subsequent eight week crossover or continuation phase. SETTING--Outpatient clinic. SUBJECTS--60 patients (51 women) aged 18-60. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE--Weight loss. RESULTS--After eight weeks of treatment the mean weight loss in the cimetidine group (5.7 kg) was similar to that of the placebo group (5.9 kg; p = 0.78, 95% confidence interval -2.0 to 1.5 kg). Body mass index, waist and hip measurements, waist-hip ratio, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures decreased similarly in the two groups. No association was found between weight loss and the patients' ability to guess if they were being given drug or placebo. Correct guesses of current drug were more prevalent than expected by chance (25/37 correct, p = 0.05 for the parallel group phase; 26/30, p = 0.0001 for the crossover phase). CONCLUSIONS--Cimetidine had no effect on weight loss in moderately obese patients. The study underlines the potential problem that blinding of patients to treatment can be compromised.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersen T., Astrup A., Quaade F. Dexfenfluramine as adjuvant to a low-calorie formula diet in the treatment of obesity: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992 Jan;16(1):35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell K. D., Stunkard A. J. The double-blind in danger: untoward consequences of informed consent. Am J Psychiatry. 1982 Nov;139(11):1487–1489. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.11.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROMIE B. W. THE FEET OF CLAY OF THE DOUBLE-BLIND TRIAL. Lancet. 1963 Nov 9;2(7315):994–997. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)90693-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gøtzsche P. C. Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Control Clin Trials. 1989 Mar;10(1):31–56. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASAGNA L. The controlled clinical trial: theory and practice. J Chronic Dis. 1955 Apr;1(4):353–367. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(55)90090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis T. A., Lavori P. W., Bailar J. C., 3rd, Polansky M. Crossover and self-controlled designs in clinical research. N Engl J Med. 1984 Jan 5;310(1):24–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198401053100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASH H. The double-blind procedure: rationale and empirical evaluation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1962 Jan;134:34–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidell J. C., Cigolini M., Charzewska J., Ellsinger B. M., Contaldo F. Regional obesity and serum lipids in European women born in 1948. A multicenter study. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1988;723:189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1987.tb05943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]